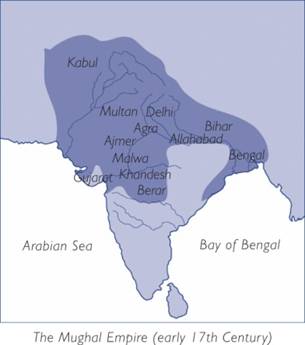

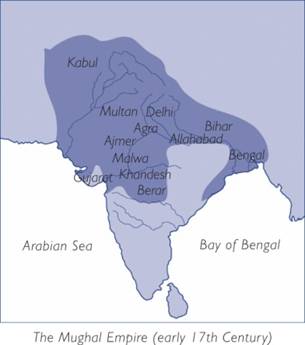

The Mughals, descendants of the Mongols, ruled India for about three centuries, leaving behind a rich political and cultural legacy. Their reign was marked by a number of remarkable monarchs who made a significant contribution to India’s art, architecture, customs, education, religious beliefs and governance. The empire had its share of political machinations, rebellions and anarchy, but unlike the disparate dynasties of the Delhi Sultanate, the Mughal dynasty oversaw a period of relative peace, stability and prosperity. It began with Babur, reached its height under his grandson, Akbar, and ended with Bahadur Shah II in 1858.

Babur was a military genius who captured Delhi in 1526 and set about conquering the Rajput kingdoms in the Gangetic Plains. In 1527, he conquered a Rajput confederacy led by Rana Sangha with a decisive defeat and routed the joint forces of the Afghans and the Sultan of Bengal two years later. By the end of his military campaigns, he had become the new sovereign of India.

Babur was a man of learning and refinement who wrote poetry and was passionate about landscaped gardens, creating several in Kabul, Lahore and Agra. He was a tolerant ruler who made peace with the southern kingdoms and allowed new Hindu temples to be built. One of his first acts as monarch was to abolish cow slaughter since it was offensive to Hindus. Trade with the rest of the Islamic world, especially Persia, and through Persia with Europe, was encouraged during his regime. Babur spent his last years, before his death at the age of 48, writing his autobiography, Babur-Namah, a candid, poetic account of his illustrious life. It is said that when his son, Humayun, fell seriously ill, Babur asked God to take his life and spare his son’s. Humayun, as it turned out, made a complete recovery while Babur died a few days later.

Babur was succeeded by Humayun who proved to be an inept ruler, lacking the political wisdom of his father. In 1539, he lost the empire his father had conquered to Afghan noble Sher Shah and went into exile in Iran. In 1555, Sher Shah’s empire collapsed and Humayun returned to Delhi to restore the power of the Mughal dynasty. However, he ruled for only six months before he broke his neck during a fall and died. Humayun’s tomb, located in Delhi, has the distinction of being the first of its kind, built in a garden setting. It is listed as a World Heritage Site.

Akbar, Humayun’s son and successor, is regarded as the greatest ruler of the Mughal Empire. Akbar was only aged 13 when he became the head of the powerful Mughal Empire after the sudden death of his father. He went on to rule the empire for 49 years. With the able guidance of his guardian, Bairam Khan, the young Akbar expanded the empire by conquering Gujarat, Bengal, Kashmir, Sind and Rajasthan. He developed a system of autonomy to rule the imperial provinces and placed military governors in every region. According to this system, the Hindu territories were under the control of the emperor but still largely independent—the British used the same model of governance when they took over India in the 18th and 19th centuries. Akbar also allowed Hindus to use their own law, rather than Islamic law, to regulate themselves.

To foster good relations with the Hindu-ruled kingdoms, he married Rajput princesses, and is believed to have had over 5,000 wives. His favourite wife was a Hindu and the mother of his successor, Jahangir. He also placed Hindus in key positions in his administration to unify Hindus and Muslims in the empire. In a radical move in 1564, Akbar abolished the hated jizya tax levied on non-Muslims; he had removed the pilgrimage tax paid by Hindus travelling to pilgrimage sites the preceding year.

Akbar believed in freedom of worship and religious tolerance, and tried to find a unifying element in all the faiths that were practised in his kingdom. He sponsored debates at his court between Christians, Hindus, Zoroastrians and Jains, and eventually broke away from conventional Islam and came up with a new religion, Din-i Ilahi or ‘The Religion of God’. The religion was based on Islam and contained aspects of Jainism, Zoroastrianism and Hinduism: from Jainism, it took the principle of respect and care for all living things, while borrowing the Zoroastrian concept of sun worship and divine kingship. The religion died with Akbar in 1605.

Shunning Agra, Akbar built the sandstone city of Fatehpur Sikri (City of Victory) as the new capital of his kingdom. However, he abandoned Fatehpur Sikri after just 14 years because of problems with the water supply. The city remains in good condition even today, constituting a significant legacy of Akbar’s rule. Located west of Agra in Uttar Pradesh, it is a synthesis of Hindu and Muslim architecture. It holds a mosque, a palace, sprawling gardens, public buildings, bath houses, a worship hall for Din-i Ilahi and a tomb for Akbar’s religious advisor, Shaykh Salim Chishti. Akbar was particularly indebted to Chishti because he foretold the birth of the Mughal emperor’s first son.

Art, particularly miniature paintings, blossomed under Akbar’s patronage, as did music. Singer Mian Tansen, who created classical North Indian music for Akbar, was one of the nine gems of his court, and a particular favourite. Birbal who specialised in wit and humour, was another gem of Akbar’s court.

An illiterate Connoisseur Of Literature

Akbar never formally learned to read or write but was a connoisseur of literature. Hindi literature grew in popularity, with Tulsi Das being one of the most celebrated Hindi writers of that period. Sanskrit texts were studied extensively and translated into Persian. Akbar also established numerous institutions of learning throughout his kingdom, notably in Delhi, Agra and Lahore.

Akbar was succeeded by his son, Jahangir, who reinstated Islam as the state religion while continuing Akbar’s policy of religious tolerance. Jahangir did not pursue military conquest as forcefully as his father, but he did manage to assert Mughal rule over Bengal in eastern India. Jahangir’s tenure is considered the richest period of Mughal culture, and he is best remembered for the magnificent monuments, buildings and gardens he built. His reign was also a period of opulence with luxurious palaces, lavish festivities and processions of silk-caparisoned elephants. Jahangir, known to be both tender and brutal, loved nature and art and lavished money on both. Along with his favourite wife, Nur Jahan, he patronised the arts and encouraged artists to create a unique Mughal style of miniature painting. Nur Jahan took charge of many of the palace affairs while Jahangir indulged in his pleasures, such as drinking arrack, a local alcoholic brew laced with opium. When Jahangir died in 1627, it was Nur Jahan’s son, Shah Jahan, who ascended the throne.

Shah Jahan’s biggest legacy is the magnificent buildings he built, notably the Taj Mahal, the Agra Fort and the Red Fort. His opulent golden, jewel-encrusted throne was known as the Peacock Throne, named after its canopy held by 12 pillars decorated with peacocks.

Shah Jahan was also as keen on conquest as his ancestors; the empire began to expand once more during his reign. As part of his military pursuits, he quelled a Muslim rebellion in Ahmadnagar defended by Maratha noble Shaji Bhonsle, and annexed the territory. He also tried to destabilise the Deccan sultanates of Bijapur and Golconda by creating trouble between the Maratha chieftains and the sultans. Shah Jahan was responsible for shifting the seat of power from Agra back to Delhi.

Shah Jahan was devastated by the death of his beloved wife, Mumtaz Mahal, in 1631, during the birth of their 14th child. Thereafter, he devoted all his time to building monuments across the kingdom, notably, the world-famous Taj Mahal. Located in Agra, this mausoleum to his wife was started in 1632 and took almost 20 years to complete. Shah Jahan also built Shahjahanabad, the area that is present-day Old Delhi, which was the seat of Mughal power in Delhi. Shahjahanabad holds the Red Fort and the Jama Masjid, the largest mosque in India.

The Red Fort, built of massive blocks of sandstone, took ten years to complete. It consists of public and private halls, marble palaces, a mosque and lavish gardens. Despite attacks by the Persian Emperor Nadir Shah in 1739, and by British soldiers in 1857, the Red Fort still stands as a striking symbol of Mughal rule in Delhi.

Taj Mahal

Shah Jahan is best known for the exquisite Taj Mahal, his labour of love for his late wife, Mumtaz Mahal. It took 20,000 labourers to complete the marble structure that is set in a Persian landscaped garden on the banks of the Yamuna River. The site was selected because of its location on a bend in the river, so that it could be seen from Shah Jahan’s palace at the Agra Fort. Shah Jahan engaged labourers and artisans, and sourced marble, sandstone and semiprecious stones used for the marble inlay work from all over India and abroad. The pure white marble came from Makrana in Rajasthan, crystal and jade from China, lapis lazuli and sapphires from Sri Lanka, carnelian from Baghdad and turquoise from Tibet. The master mason came from Baghdad.

The Taj Mahal is made up of four minarets surrounding a central dome. An ornate marble screen, finely carved to produce the appearance of lace, surrounds the cenotaph in the central hall. The actual graves of Mumtaz Mahal and Shah Jahan lie in an underground crypt directly below the cenotaphs. The white monument reflects the changing light of the day, dazzling one minute, glowing the next and shimmering in the moonlight.

Shah Jahan fell ill in 1658 and was imprisoned by his son Aurangzeb in Agra shortly afterwards. Aurangzeb then executed his elder brother and captured the throne, declaring himself as the ruler of the vast Mughal Empire. Shah Jahan died a few years later in 1666.

Aurangzeb, the last of the illustrious Mughal rulers, expanded the empire to its fullest extent. He seized the southern kingdoms of Golconda and Bijapur and captured all the territories held by the Marathas who continued to resist using guerrilla warfare tactics. He eventually established a state in the Western Ghat region in south-west India, in present-day Maharashtra.

Aurangzeb was a pious Muslim who ended the policy of religious tolerance advocated by his ancestors. He insisted that the sharia (Islamic law) be followed by everyone and he reimposed the jizya tax on non-Muslims that Akbar had abolished. He also introduced a new custom duty and levied a higher rate of tax on non-Muslims, creating considerable unrest among Hindus. A staunch Muslim, Aurangzeb forbade drinking and gambling in his empire and imposed Islam on his subjects. He was responsible for crushing a Hindu religious sect, the Satnamis, and beheading the ninth guru of Sikhism, Tegh Bahadur. The Sikhs, religious reformers who turned militant under the Mughals, revolted against Aurangzeb’s rule and continued their hostilities towards the empire. By the early 1800s, they had succeeded in carving out an independent kingdom with the capital at Lahore.

Among other unpopular moves, Aurangzeb withdrew lavish state support of the arts although he continued to patronise intellectuals and architects whose works—such as the Pearl Mosque in Delhi—were related to Islam. However, he destroyed hundreds of Hindu temples and other non-Muslim places of worship during his rule of terror.

Aurangzeb died in 1707 at the age of 88, leaving a Mughal empire weakened by growing unrest among Muslims and Hindus, constant conflict and a depleted treasury. One of his four sons, Bahadur Shah I, took over control of the empire but it never regained its past glory. The subsequent Mughal emperors were ineffectual puppet leaders who merely had a nominal presence. By the time Ahmad Shah took over the Mughal throne in 1748, the power of the empire was all but extinguished. India was divided into regional states which, while recognising the nominal supremacy of the Mughals, wielded considerable power and influence. The Mughal Empire officially came to an end in 1858 when the last ruler, Bahadur Shah II, was deposed by the British and exiled to Burma.

The Rise Of The Marathas

The first major threat to Aurangzeb’s authority came from the Marathas, a powerful group of warriors operating in the Western Ghat region, in present-day Maharashtra, under Shivaji Bhonsle. Shivaji instilled patriotism and devotion to Hinduism in his people and inspired them to rebel against Aurangzeb’s tyrannical policies. Against all odds, the indomitable Shivaji established a Hindu kingdom in 1674 and declared himself Chatrapati or the King. He extended his territory to claim Nasik and Poona in the east and Vellore and Tanjore in the south. Shivaji died at the age of 53 and was succeeded by his son Shambaji, who was captured and killed by Aurangzeb. Despite their setbacks, the subsequent Maratha leaders remained steadfast in their goal of a Maratha homeland and continued to rebel against the Mughals, as well as British imperialism at a later stage.

In the early 18th century, power passed to the Peshwas, who were prime ministers under the descendants of Shivaji. Nana Saheb was a Peshwa who became one of the most powerful rulers in India, with an empire that extended from the Deccan to Gujarat, Rajasthan and Punjab. He died shortly after the Third Battle of Panipat when Afghan armies led by Ahmad Shah Durrani defeated the Marathas. The Maratha power declined after this battle and was further crippled by the British, led by Mountstuart Elphinstone, who occupied the office of Resident (Pune) in 1811. Maratha leader Bajirao II finally submitted to the British on 3 June 1818, signalling the end of the glory of Maratha power.