INTRODUCTION

All in the Family: Sources of Stress

The Stress of Military Life

Courage is the price life exacts for granting peace.

—Amelia Earhart

Imagine yourself sitting in front of the television watching the 6:00 news. You see a news clip come on where the anchor says, “Another roadside bombing occurred today in Kabul. It is confirmed that 25 more U.S. soldiers were killed.” The anchor changes the topic and talks about something else. But what is it like for the wife who just got married to her military husband, expecting to have their first child? Could this be the end of their relationship? Is he safe? Did he make it out alive.

What about to a 6-year-old girl? Her heart races and drops in her chest, as she cries to her mom, “Mommy, is Daddy dead?” This happens every time they hear bad news. She is young, but she knows that her dad is fighting in a war. She feels the stress every day. When she sits at her desk in school, trying to focus on her homework, her mind wanders to the days when her dad was at home and safe. Now, it seems like all she worries about is whether or not he is alive. Will her daddy come home for her next birthday, or for Christmas.

They just got new orders from their command. She is getting deployed overseas, while her husband and 3-year-old daughter stay behind for a year. This is her third move in five years. Her daughter will learn to read without her. Will her daughter remember who she is when she gets back? What will her little girl think of her? Will she think that her own mother doesn’t love her, or that she abandoned her for a year of her life.

Their 19-year-old son just got deployed to Afghanistan for the first time. He just joined this past year and finished boot camp. His mother, father, and sisters get the word that he has been injured in the line of duty, but no one will tell them how badly he has been hurt. Where is he? How is he? What happened? Can he come home? So many questions are left unanswered. So much silence in the room. What is there to say at a time like this.

They are sitting at the dinner table having a family dinner, but no one feels like eating. It is the dinner hour they will never forget as long as they live. They had a knock at the door with a message from a military officer that their 22-year-old son was killed by a roadside bomb in Afghanistan. The military will be making arrangements for the body to be flown over for a military memorial service. The body? His parents, who are in their 50s, sit dumbfounded. Sure, everyone knows it could happen–but not to their son. They were supposed to go first–not the other way around. It wasn’t supposed to be that way.

The Reality for Military Families

These are all experiences that a typical civilian family can’t dream of going through. Yet, to a military family, it is everyday life. It is typical. It is frequently hard, with lots of uncertainties, lots of change, and a lot of adjustments to be made. This is what it is like for more than 3.1 million individuals who are part of a military family. This is the experience of more than 2 million children. How do they do it? Being a military family comes with the cost of learning to adjust to change.

Many families move through the transitions with relative ease, but many others struggle with trying to negotiate the challenges at different phases, with each relocation, deployment, redeployment, and reunion. Because of repeated deployments, the current veterans of Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OEF/OIF) are at a high risk for mental health problems (e.g., Hoge et al., 2004), including high rates of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, drug and alcohol abuse, and traumatic brain injury (TBI). Recent research shows that spouses of active-duty soldiers deployed to war also are at a high risk for mental health problems compared to spouses whose husbands did not deploy (Mansfield et al., 2010). Specifically, wives of soldiers who deployed for less than 11 months had an 18% higher rate of suffering from depression compared to wives whose husbands did not deploy. The rate was 24% higher when soldiers were deployed 11 months or longer. Therefore, it is apparent that the struggles associated with deployment are taking a toll on families.

As with any difficulties in life, those experiences can either strengthen or weaken an individual. In a relationship, the challenges can bond the individuals together and solidify that connection, or they can make family members become more separate and disconnected from one another.

Military Culture and Therapy

A common criticism that service members have about mental health clinicians is that civilian clinicians have little knowledge about the military or about the wars in which the returnees may have participated. Service members sometimes resent having to explain military acronyms, command structure, the differences between services, and facts about the OEF/OIF wars to their therapists. Therefore, civilian clinicians who work with military families should make themselves familiar with military life, activities, and culture.

Military Branches and Values

Whereas all U.S. military services follow the same general structure of ranks and responsibilities for enlisted personnel, noncommissioned and commissioned officers, each service and branch of the military has its own culture and language. In order to understand what’s going on with a career Marine, for example, it is important to understand Marine culture, history, and language. This may include having an understanding of Marine ranking labels, use of acronyms, and stated values. Taking the time to learn about military culture and the experiences that clients may have had serving our country will facilitate rapport and validate the returnee’s internal frame of reference.

Military Beliefs and Help-Seeking

A crucial point to understand is that the beliefs held by service members can directly impact their family members and hinder them from seeking mental health care. Some strong belief systems include gender role identity and those related to mental health stigma. These beliefs can also greatly affect the relationships among military family members.

Gender Role Identity

Not surprisingly, many personal beliefs held by service members are consistent with ideologies underlying masculine gender role identity. Individuals who hold masculine gender role ideals tend to value attributes such as independence, self-reliance, competition, power, strength, and emotional control. These values can impact the therapeutic relationship as well.

On the one hand, such values can positively impact the therapy environment by helping service members be proactive in participating in their therapy process. On the other hand, it is important to be aware that those individuals who hold traditionally masculine ideals often run a greater risk of developing health problems and tend to utilize health care services less often than those without these ideals (Bowman & Walker, 2010). This is particularly true for mental health problems. The belief that one ought to be able to handle mental health problems on one’s own is much higher in men who have traditional masculine values (e.g., Sayer et al., 2009; Stecker, Fortney, Hamilton, & Ajzen, 2007). These masculine military values often trickle down to the family members. Knowing about and appreciating the values that military families can bring to the therapeutic environment will help build rapport.

It is important to note that individuals who endorse traditional male role values, including service members, often view suppression of emotions as an appropriate means for dealing with stress (Lorber & Garcia, 2010). In an “open letter” to “military wives everywhere,” one service member discusses military culture and how the repression of emotions is “deeply learned through repetitious training and experience.” He writes:

Another change (that differentiates civilian culture from the military culture) is that emotions are distrusted and shunned. The mission comes first, orders are given and are expected to be carried out, and there is no place where emotional concerns come to bear. Therefore the soldier seeks to repress emotions in order to get the job done. (Military Culture: A Primer, 2011)

Individuals who hold traditionally male values often view coping tactics that help them suppress their emotions (such as heavy drinking or other addictive behaviors) as a suitable means for coping with problems (Lorber & Garcia, 2010). However, coping strategies focused on suppressing emotions are counterproductive once service members return from war, and doing so tends to exacerbate mental health problems. For example, research shows that, compared to former service members who share their emotions, those who willfully suppress their emotions have higher levels of disturbing thoughts and emotions like those associated with PTSD (Shipard & Beck, 2005).

Mental Health Stigma

Service members may hold stigma-related beliefs about mental illness, such as the belief that having mental health problems is a sign of weakness (e.g., Hoge et al., 2004; Pietrzak et al., 2009). Unfortunately, stigma-related beliefs about mental illness are highest among service members who screen positive for mental health issues (e.g., Hoge et al., 2004; Whealin et al., 2011).

In one large study, less than one-third of service members, including Marines who acknowledged a need for mental health care, actually accessed available services. When asked about the barriers to obtaining treatment, the service members who said they needed mental health care endorsed stigma-related beliefs about treatment as the greatest barrier to seeking services (Hoge et al., 2004). In therapy, clients who hold traditional male gender role values and stigma-related beliefs may be more likely to conceal or underreport mental health problems. We will discuss these types of beliefs in more detail in Step 4.

Mental Problems as a Sign of Weakness

Research also suggests that OEF/OIF returnees who screen positive for mental health problems (compared to those without symptoms) are more likely to believe that their family members would have less confidence in them if they knew they had mental health problems, and would see them as weak (Whealin et al., 2011). In some cases, family members actually do have these attitudes. When this is the case, family members may discourage each other from openly talking about their problems (Lorber & Garcia, 2010). However, at other times, family members do not hold such beliefs, even if their service member believes they do. These families simply may be stuck in patterns that keep them from openly discussing mental health issues. Such families will need encouragement and modeling from the therapist to begin to share candidly with each other.

Unfortunately, service and family members who feel they must conceal mental health problems often experience guilt and shame about having such problems. These negative emotions often compound the problem, in that the individual suffers from the original symptoms as well as from additional emotional distress caused by shame and guilt. When others in their social environment keep symptoms to themselves as well, a family member may feel that she or he is the only one with a problem. Although such attitudes among military families are changing with time and educational outreach by the U.S. Departments of Defense and Veterans Affairs, guilt and shame about having a mental health problem are still common.

Military Culture and Treatment

The military culture vastly differs from that of civilian culture. Sometimes those common beliefs held by military service members not only prevent the military family from seeking help but can also create difficulties during treatment. It is important to recognize this issue and adapt treatments as you work with military families.

Views About Sharing Emotions

In treatment, it will be important to assess for mental health symptoms among service and family members. At the same time, we suggest exploring clients’ attitudes about mental problems and about sharing emotions. If someone does endorse stigma-related beliefs, it is helpful to openly discuss their values with them. To illustrate, if a service member reports that self-reliance and emotional control are important to him or her, talk about both the pros and cons of such ideals in the context of what it means to be a Marine, Soldier, Airman, or Coast Guardsmen. We recommend validating the fact that such values have benefits for those who possess them, including success, discipline, and in some circles, respect. Then discuss how these values can also have a downside. When applied too rigidly, such values can be maladaptive.

If relevant, talk more specifically about how military training and culture may be at odds with discussing emotions. However, emphasize that emotions have very important functions and are necessary to solve problems. Additionally, let clients know that sharing emotions is appropriate within the context of therapy. The act of suppressing emotions in the military environment may be appropriate and necessary; however, doing so in the therapeutic context prevents military returnees from overcoming difficulties and hinders their ability to connect with family members. Similarly, if a returnee or family member suffering from mental health problems endorses mental health stigma, it will be helpful to normalize how common mental health symptoms actually are. In such cases, openly discuss how it is typical to feel discomfort talking about mental health problems at first. Explore any other fears that clients may have that prevent them from talking about their feelings. Once individuals feel that they have permission for sharing emotions and discussing symptoms, they will be better able to thrive individually and as a family member.

Resources for Civilians

A variety of resources are available to help civilian therapists better understand and effectively communicate with service members and their families. The U.S. Department of Defense, for example, offers an interactive online course in military culture addressing organizational structure, rank, branches of service, core values, and demographics, as well as the similarities and differences between the active and reserve components. This course is located at: http://deploymentpsych.org/training/training-catalog/military-cultural-competence.

Additionally, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs National Center for PTSD has an online course on military culture that includes military demographics, branches, rank, status, treatment, and stressors. It also addresses assessment and treatment hints for therapists. That course is located at: http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/ptsd101/course-modules/military_culture.asp.

Traumatic Brain Injury and Polytrauma Syndrome

In this section, we provide an overview of traumatic brain injury (TBI), mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI), and polytrauma syndrome. This section is only an overview, but we hope it will give you further insight into how prevalent traumatic brain injuries are and how they relate with chronic pain and PTSD. Thousands of military families have been and are affected by their loved ones sustaining injuries and requiring short-term, intermediate, and sometimes long-term care. So you will encounter military families who are experiencing the ramifications of these injuries. This chapter will give you a cheat sheet for identifying the conditions, symptoms, and treatments to help service members and returnees.

Unique Injuries in OIF/OEF

As society has advanced, protective military equipment such as Kevlar helmets, flack jackets, and advanced front-line battlefield medical care have been developed. With these advances, soldiers have been able to survive wounds that may have killed them in other wars (Gawande, 2004). On the other hand, technological advances have also included upgrades in military equipment. Subsequently, the development of devices with blast mechanisms, such as improvised explosive devices (IEDs), have resulted in an increase in the occurrence of traumatic brain injuries (TBI), mild traumatic brain injuries (mTBI), and polytrauma syndrome (Wade, Dye, Mohrle, & Galarneau, 2007). In fact, researchers have determined that there is a greater proportion of head and neck injuries in OIF and OEF veterans when compared to past wars, including World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War (Zouris, Walker, Dye, & Galarneau, 2006).

Traumatic Brain Injuries

Traumatic brain injuries are being called the “signature wound” of OIF/OEF (Hayward, 2008). Mild TBIs affect approximately 300,000 returning service members (Benge, Pastorek, & Thornton, 2009). However, other researchers have found that more than 50% of soldiers injured in combat sustain head, neck, and facial injuries (Wade, Dye, Mohrle, & Galarneau, 2007). The study supported earlier findings that 59% of the service members who were injured and hospitalized at Walter Reed Medical Center had sustained TBIs (Okie, 2005).

Prevalence of TBI

Traumatic brain injuries appear to be far more common in returnees from OIF/OEF than any other wars (Zouris, Walker, Dye, & Galarneau, 2006). In a very recent study, researchers compared the rates of TBI among active-duty personnel between the U.S. military branches. They found that Marines ran a greater risk of sustaining TBIs than those in the Army, Air Force, or Navy (Heltemes, Dougherty, MacGregor, & Galarneau, 2011). Heltemes et al. (2011) inferred that this may be so because the Marines “are an expeditionary force primarily deployed during periods of high combat intensity, and as such, it may be expected that their rates of injury due to combat are higher than the rates of injury of other services” (p. 134).

Definitions of the Conditions

As you treat service members and their families, it will be helpful to have a better understanding of the presentation for TBI or mTBI and polytrauma syndrome. We will also talk about postdeployment multisymptom disorder (PMD), a newly proposed classification for service members. In this section, we provide descriptions and definitions of these conditions.

Mild Traumatic Brain Injury

Service members who have sustained a mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) experience loss of consciousness for 30 minutes or less, loss of memory for less than 24 hours (termed posttraumatic amnesia), or feeling dazed or confused for less than 24 hours after being injured (Defense Veterans Brain Injury Coalition, 2006). Service members’ recovery time from a typical mTBI can range from a few days to a few months after being injured.

Most service members return to normal functioning within one to three months (Alexander, 1995). However, nearly 39% of service members with a mTBI still have symptoms and problems associated with their injury up to a year later (Terrio et al., 2009). Other service members experienced significant neuropsychological problems for years after they were injured. This is called post-concussion syndrome or post-conconcussive symptoms (PCSx), which is defined as “a persistent constellation of symptoms marked by cognitive, emotional, and physical complaints for many months to years after injury” (Benge, Pastorek, & Thornton, 2009).

Polytrauma Syndrome

Because OIF/OEF veterans may incur so many injuries that require care, the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) now classify more complex cases as polytrauma syndrome (Department of Veterans Affairs, 2009). Service members who present with polytrauma syndrome have sustained injuries to multiple body systems, which may or may not include TBI. When service members present with symptoms that cannot be clearly categorized, this is referred to as medically unexplained symptoms (MUS), which can include physical, psychological, or cognitive problems (Uomoto & Williams, 2009).

Postdeployment Multisymptom Disorder

Researchers have suggested that it is typical for returning service members to have the combination of postconcussive syndrome, chronic pain, and PTSD (Clark et al., 2007; Clark et al., 2009; Lew et al., 2009). Furthermore, researchers have concluded that this combination is unique to OIF/OEF returnees (Walker, Clark, & Sanders, 2010). Lew et al. (2009) found that 42% of returning service members had chronic pain. There appears to be an overlap of these symptoms in OIF/OEF returnees (Clark et al., 2009). As such, Walker, Clark, and Sanders (2010) proposed that this multisymptom presentation should be called postdeployment multisymptom disorder (PMD), which may include problems such as sleep disturbance, irritability, concentration and attention difficulties, fatigue, headaches, musculoskeletal problems, affective disturbance, apathy, personality changes, substance abuse, avoiding activities, problems in work or school, problems in relationships, and hypervigilance.

Blast Injuries

Improvised explosive devices (IEDs) cause what are called “blast injuries,” which appear to be more unique to the OIF/OEF wars (Moore & Jaffee, 2010). There are four levels of blast injuries: primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary. We briefly describe them here.

Primary Blast Injuries

Primary blast injuries are typically caused by what is referred to as “barotrauma.” That is, when an IED explodes, the pressure of the blast causes trauma to the tissues. Service members who sustain primary blast injuries can have any of the following (or combination of injuries): ruptured ear drums, pulmonary embolism, ruptured colon, ruptured small or large intestine, damage to the kidneys, spleen, or liver, facial fractures, or serious eye damage or blindness (DePalma, Burris, Champion, & Hodgson, 2005).

Secondary Blast Injuries

When the explosion has settled to some degree, fragments and chunks of metal can cause serious shrapnel wounds and penetrating injuries. These are considered to be secondary blast injuries and have been found to be the leading cause of death and injury in service members and civilians (DePalma, Burris, Champion, & Hodgson, 2005).

Tertiary Blast Injuries

Tertiary blast injuries are caused by structures collapsing, such as vehicles and buildings, and “they result from people being thrown into fixed objects by the wind of explosions. Any body part may be affected, and fractures, amputations, and open and closed brain injuries occur” (DePalma, Burris, Champion, & Hodgson, 2005, p. 1338).

Quaternary Blast Injuries

Quaternary blast injuries are essentially any injuries that were caused by the force of the blast, which did not fall into one of the other three classifications. Quaternary injuries may include burns, poisoning from chemicals and gases emitted from the explosion, asphyxiation, or exposure to radiation or asbestos.

Treating Wounded Service Members and Their Family Members

The point to understand is that service members can sustain one or more than one level of blast injury. They may sustain serious second- or third-degree burns requiring skin graft surgeries. They may be deaf or blind as a result of the blast. They may have mild or serious TBI. It is likely they will have chronic pain and PTSD. As such, returning service members will have a lot of physical as well as mental healing to do after these events. Once they have been medically discharged and sent home, their rehabilitation will continue. It is imperative that the family be educated and supported as well, so they can support their loved one. However, that process begins with you having information about how to help the service member and family, from the clinical presentation to assessment and treatment.

Clinical Presentation

Once service members have gone home, their treatment will continue. Assuming it is a few months after they were injured, they will present with some ongoing problems related to TBI, pain, or PTSD. As stated earlier, it is very common for service members to have mTBI, PTSD, and chronic pain (Clark, Scholten, Walker, & Gironda, 2009). And you will find that there is some symptom overlap when returnees have polytrauma syndrome. Here are symptoms and problems that seem to occur in both mTBI and PTSD:

- Distractibility

- Attention deficits

- Poor working memory

- Slower processing speed

- Problems with executive functioning

- Impulse control problems

- Irritability

- Reduced verbal processing

(Adapted from Campbell et al., 2009; Cooper et al., 2010; and Morrow, Bryan, & Isler, 2011.)

Confounds With Diagnosing TBI Versus PTSD

Sometimes it can be difficult months after service members have been wounded to differentiate whether they have residual symptoms of TBI, or if it is PTSD. That is because there is an overlap between symptoms. For example, Kennedy, Leal, Lewis, Cullen, and Amador (2010) found that, “There is something about mTBI itself that conveys risk for subsequent PTSD” (p. 228). The authors suggest that clinicians address the reexperiencing symptoms from PTSD in order to ameliorate the TBI. Because of the overlap of symptoms, clinicians who assess returning service members after the traumatic events may have difficulties teasing apart and differentiating which condition is which.

Other researchers have pointed out the problems with confounding variables when assessing and diagnosing returning service members. For example, Summerall and McAllister (2010) stated: “Many service members today are exposed to multiple psychological and biochemical traumas, occasionally during the same combat episode. Clinicians evaluating these conditions should bear in mind these limitations to the current diagnostic schema” (p. 564).

Assessment Guidelines

It can be helpful to administer screening instruments to assess for specific symptoms and presentation. In addition, it is important to obtain a very detailed history. A detailed clinical assessment may include the following components:

- PTSD symptom checklist (Military), PCL-M

- Trail-making test, Part B

- Structured diagnostic interview

- Military history (where they served, how long, how many deployments)

- Psychosocial functioning before injury

- Specifics about events causing injuries (what happened before, during, and afterward)

- Medical history

- Developmental history (past school performance, history of head injuries, learning disabilities or difficulties)

- Substance abuse history

- Trauma history

- Current psychosocial functioning (relationships, current stressors, living situation, etc.)

- Current functioning (symptoms, disabilities, conditions)

Treatment Considerations

Some researchers suggest that rehabilitation and treatment efforts should focus on reducing reexperiencing symptoms with prolonged exposure therapy (e.g., Kennedy et al., 2010). However, other researchers suggest that when service members have reduced verbal processing speed, therapies such as prolonged exposure and cognitive processing therapy may not be as effective (Campbell et al., 2009). Campbell et al. (2009) suggest that “treatment for those with comorbid TBI/PTSD may require adapting these evidence-based therapies to include slower verbal processing” (p. 802). Other researchers suggest that “a recovery-oriented approach emphasizing that improvement in one functional domain can lead to improvement in another should inform treatment planning” (Summerall & McAllister, 2010, p. 568).

An extremely important consideration is that the returning service members will not go through treatment in isolation. They will reintegrate into society and into their family. This can pose several challenges (Whealin, DeCarvalho, & Vega, 2008a; Whealin, DeCarvalho, & Vega, 2008b). The added stress of injury, mTBI or TBI, chronic pain, and/or PTSD further complicates the treatment picture. The service member will face a lot of challenges in his or her rehabilitation process.

Supporting the Military Family

It is imperative that the family members, from spouse or partner to parent(s), to siblings, to extended family and friends, provide support. Having said that, it is equally important to ensure that the family is supported as well, because it can be incredibly stressful, frustrating, and emotionally painful for family members to watch their loved one suffer. At times, military family members may feel frustrated and helpless because they can’t fix the situation, and they sometimes can’t do much to help their loved one. Military families can go through huge adjustments when their loved one is injured, medically discharged, and then having long-term physical and/or psychiatric difficulties because of war experiences.

Effects on the Military Family

Because the returnee may not be fit to work any longer, a spouse may need to be retrained for a job or shoulder some or most of the financial burden. Financial strain can sometimes lead to foreclosure and further relocation. Family members may feel isolated from other loved ones because of the time, energy, and focus that goes into rehabilitation. Some spouses may not know how to handle it if their loved one loses his or her temper or says inappropriate things because of a brain injury. Some spouses may provide secondary gain when their loved one bows out of doing household chores or having responsibilities because of their chronic pain condition(s). These are just a few of many potential difficulties the military family may face, and they are all very important scenarios to consider as you turn your attention toward helping military families to heal.

Vicarious Trauma in the Military Family

Vicarious traumatic stress is a term that refers to someone developing traumatic stress symptoms by hearing about someone else’s trauma secondhand and being impacted over time by someone who is suffering from PTSD. Vicarious traumatic stress can come about gradually from listening to stories or news reports about traumatic events. It can also come about by living with someone who is suffering from PTSD.

Vicarious Trauma in Family Members

Family members who develop vicarious traumatic stress can develop the same types of symptoms their service member is experiencing.

Symptoms Family Members May Experience

Some family members may find themselves thinking about upsetting stories or images even when they are not trying to think about them. Others may have dreams or nightmares about the events their service member has experienced. Like the service member, family members may feel like they have to be on guard all the time. They may become startled following sudden noises, feel very anxious, or have trouble falling or staying asleep. Family members of service members may also experience avoidance and go out of their way not to think or talk about deployment or other war-related topics. Family members can experience emotional numbing and begin to feel detached from other people, or they may feel fewer positive feelings, such as happiness.

Transfer of Beliefs to the Family

In addition to vicarious trauma, family members may experience direct stress that results from a service member’s PTSD symptoms. For example, trauma survivors who have developed hypervigilance may attempt to teach their families to be afraid of crowded or unknown environments. During deployment, service members adapted to living in a dangerous and/or foreign environment. As a result, they may have developed new beliefs and behaviors, which they can transfer to their families without even knowing it. For example, a service member who does not go to shopping malls because he has learned that crowded places can be very dangerous may pass on his fear of crowded malls to his daughter. He may be very overprotective and forbid his daughter to go to shopping malls. Over time, his daughter may adopt hypervigilant behavior and begin to avoid crowded places as well.

Other Effects on Family Members

A service member’s combat stress symptoms can also directly harm, and even traumatize, family members, especially when combined with other problems. For example, research has shown that families experience the most distress when their service member with PTSD has difficulty regulating anger and other emotions (Galovski & Lyons, 2004). When a service member is highly irritable and/or cannot control his or her anger, family members often become targets of that anger, leading to conflict and sometimes abuse. It is not surprising that postdeployment families experience more problems and divorce than other families. This is why it is extremely important for everyone in the family to understand how and why a service member’s PTSD is affecting them, and they need to take action to not harm one another.

Other Forms of Vicarious Traumatization

There are other ways that military family members can be affected by the service member’s stress. These are referred to as secondary traumatic stress and compassion fatigue.

Secondary Traumatic Stress

A term related to vicarious traumatic stress is secondary traumatic stress. Although the terms are often confused, secondary traumatic stress refers to stress reactions that are caused by directly witnessing another person’s exposure to trauma (Ruzek, 1993). The viewer’s life is not threatened, but he or she experiences fear, helplessness, or horror as a result of looking at pictures, a video, or being a bystander during a traumatic event.

Compassion Fatigue

One other related term, usually applied to those in professional caregiving positions, such as nurses, is compassion fatigue. Compassion fatigue refers to the negative changes that can occur over time when a person cares for someone who is suffering from psychological or physical ailments. Symptoms of compassion fatigue include hopelessness, a decrease in experiences of pleasure, anxiety, and a negative attitude.

The 8 Steps Visited

As long as you live.

Keep learning how to live

—Seneca, 4 B.C.–65 A.D.

In our lives, we can keep going along as we always have, expecting that things will change or improve. In the addictions or chemical dependency field, there is an adage. It states that the definition of insanity “is to keep doing the same thing over and over, but to expect different results.” As you are aware, expecting different results from doing the same thing is rather ridiculous and pretty contradictory. The reality is that if we want to grow in life, we need to be willing to change at various points in our lives. Usually, painful or joyful life experiences serve as catalysts that help us make life changes. Other times, boredom or dissatisfaction with how things are causes us to question why we are doing what we are, and to explore other options. This book is about exploring options. It is about offering solutions and different, healthier ways of doing things.

The 8-Step Approach to Healing the Military Family

The 8 Steps are essentially the roadmap to better relationships for the military family. As is part of life, there will always be normal setbacks and milestones, but within the unique culture of the military, the family experiences numerous added stressors that create significant challenges. We will help the family solve these problems, meet their challenges head on, and successfully master them.

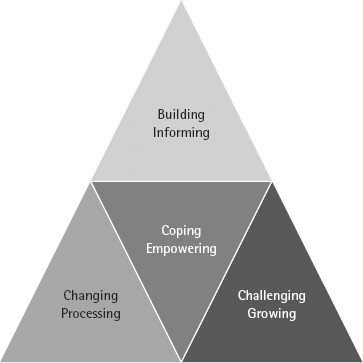

In the diagram that follows, you can see that we have defined the steps in the context of a pyramid. Within the pyramid, you will find the processes that military families will go through as they conquer each of the steps. In using this top-down approach, families will begin with building and informing, moving down to coping and empowering, then changing and processing, and finally challenging and growing. Throughout this book you will see this pyramid highlighted for the specific process through which you will lead your family.

At the core of this healing and strengthening process is positive coping and empowering. Dealing with stress in a healthy manner, and being empowered to move ahead and conquer higher challenges, are central facets in the 8 Steps. When families know how to handle stress as it impacts them, and know they have what it takes to deal with it, they will more confidently move ahead in life. They will also be stronger and more resilient in meeting life’s challenges.

Here is a sneak peak at the 8 Steps. Within each of the steps, there are very specific key issues and challenges that commonly occur within military families, so the goal is for family members to work through those issues together.

Building/Informing

At the beginning of this process, the family will start with reconnecting. The family will learn to build the connection and inform/explain their perspective. In STEP 1, family members will CONNECT with one another again. You will guide them through the process of building the connection and improving communication.

Once they have reestablished a positive connection with one another, the family will arrive at STEP 2, wherein they EXPLAIN their perspective to each other. In Step 2, you will guide the family through the process of learning how to effectively and sensitively communicate and become more informed about each other’s experiences.

Coping/Empowering

In STEP 3, you will help military family members to DISCOVER what helps in their relationship, and what coping skills will help them to more effectively deal with life’s stress. Their process will involve discovery and practice of powerful coping skills. By taking good care of themselves, the family can move to the next level.

In STEP 4, you will help EMPOWER family members. In this step, the family learns to focus on one another’s strengths. They learn to use those strengths to deal with the key issues they will face.

Changing/Processing

At this point, the family faces challenges with trust and intimacy. Family members may have inaccurate perceptions or thoughts about others in the family, which may be leading to anger and resentment. In STEP 5, you will help the family IMPROVE their thoughts, beliefs, feelings, and behaviors. You will guide them through the process of becoming more aware of their negative thoughts and beliefs, which are particularly relevant to sexual intimacy. The family will learn to break the habits of negative thoughts and beliefs and change the course of their relationship at a deeper, more intimate level.

In STEP 6, we provide healthy ways that the family can share their intimate fears, thoughts, and feelings. You will learn how to PROCESS painful experiences that military family members may have had, which to this point have prevented the family from moving ahead in their lives. The family will work together to understand and unconditionally accept one another.

Challenging/Growing

The family is now equipped to set powerful, higher-level goals for themselves because they have conquered all of the core issues that were previously holding them back. With newfound energy and trust, family members learn in STEP 7 to set positive, powerful, short- and long-term goals as individuals and as a family. You will learn how to help the family CHALLENGE themselves and work together as a family toward achieving their most important goals in life. Meeting new challenges will help the family to reach the final step’growth.

In STEP 8, the family is ready to GROW together and become resilient. They learn how to further reinforce their individual and collective strengths as a family. They learn to become resilient, able to face new challenges in their lives in ways that are now positive, healthy, and empowering for everyone.

The Road to Healing in the Military Family

Our intent is not to point out faults, focus on problems, or to judge. Our intent is to highlight areas that can be improved upon. No one is perfect. Everyone has problems. That is not the issue. The key to healing and becoming stronger as individuals and as families is to acknowledge those areas of difficulty, then to adapt and adjust accordingly. In the words of Thomas Edison, “There is a better way to do it. Find it.”

We would like to offer better ways of doing things for the family. By taking these steps and practicing these new, improved methods of interacting with one another, the family will quickly be on their way to healing, wellness, and success in their relationships. This is what we hope every military family will achieve as a result of working through this book. Now let’s get started!