STEP 4

Empower

Communication. It’s the first thing we really learn in life. Funny thing is, once we grow up, learn our words and really start talking, the harder it becomes to know what to say, or how to ask for what we really need.

—Grey’s Anatomy Television Series, Shonda Rhimes Second Season, “Something to Talk About”

Michael and Lisa are back in my office one week later with their 12-year-old daughter, Abby. This is the first session that Abby has attended, so I spend some time introducing myself. Because she has never been in family therapy, and in order to make her feel comfortable, I also take a few minutes to explain to Abby what her parents and I do when we meet together. I let her know that she can join in today’s conversation if she likes, and that I look forward to hearing her input. Then I turn the focus to reviewing Michael and Lisa’s week with them. In order to help the family understand the importance of homework, it helps for you to hold the family members accountable every week for following through on it. Last week, Michael had agreed to spend some time every day working in the yard to destress. Lisa agreed to practice progressive muscle relaxation and to write about all of her concerns and feelings in a journal for 10 minutes a day.

THERAPIST: So, how did your homework go? Did you practice your coping activities for the week.

LISA (with an acerbic tone): Well, one of us did.

THERAPIST: How so? (I am careful not to collude with Lisa’s sarcastic tone.)

LISA: I did my homework every night.

THERAPIST: How was that for you.

LISA: It was such a break! I cannot believe how taking just a 10-minute break could recharge me.

THERAPIST: You are seeing the benefits of coping proactively. I’m really glad you were able to take the time to do that, Lisa.

LISA (smiling): Thanks. I only wish that Michael would do better.

THERAPIST (I pause and look at Michael): Michael, how did your homework go?

MICHAEL (looking somewhere in the distance out the window): Okay.

THERAPIST: Tell me about it.

MICHAEL: Well, I spent time with Abby when she (Lisa) was relaxing. But I guess I never made it out to the garden to get any work done.

THERAPIST: Good! I’m glad to hear you spent time with Abby.

LISA (folds her arms): You were supposed to do something with Abby, to interact with her. I don’t call watching sports interacting.

THERAPIST: (I wait for Michael.)

Michael (growling, as he looks back out the window): Here we go again.

When deployments involve high levels of chronic stress and/or traumatic events, returnees may be experiencing bereavement, posttraumatic stress, or depression. When there has been a physical injury, returnees as well as family members need time to psychologically adjust to the disability or associated difficulties, such as chronic pain. In the first few weeks following deployment, the family may need to be guided to give the returnee extra space in order to readjust. However, over time, it is important for returnees to address any problems that linger. With time, service members can resume their role as a spouse or partner and, if children are involved, their role as a parent.

Many returnees experienced the harsh realities of war. They may have witnessed suffering and death, destruction, or atrocities. Many have to come to terms with killing people during war. Many returnees have difficulty dealing with some of those realities. Some may have horrific memories that they frequently reexperience. They may need time to grieve and to come to terms with moral injustices that they may have witnessed. All of these experiences often result in changes in the military family.

One of the key issues that come into play following disabling injuries is the shift in roles and responsibilities between partners. Even when physical or psychological injuries are not an issue, deployment-related shifts in roles and responsibilities require attention. When the changes lead to new patterns of behavior, a family must flexibly adapt to those changes. However, if family members do not communicate what they are experiencing, what they are feeling, or how they have been impacted by change, other family members can feel confused, angry, and resentful.

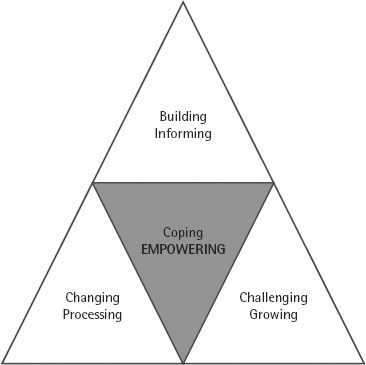

In Step 4, we help family members communicate on a deeper level, so they feel more connected as a unit. In doing so, we help family members strengthen their trust in each other. In this step, you will learn ways to facilitate open communication among the family members. Family members will learn to go beyond their feelings of vulnerability with one another and to focus on each other’s strengths. As part of this step, family members will be able to face and express their feelings of sadness and anger to their loved ones.

For Your Information: Social Isolation, Mental Health, and Social Sharing

As mentioned previously, when a returnee is suffering from symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or depression, his or her symptoms can directly and indirectly compromise social relationships within a family. Both disorders are associated with social isolation and emotional numbing, which can make people less likely to seek out and engage in relationships with others. Service members and veterans who have PTSD, in particular, have been shown to socially withdraw from others over time, compared to those without PTSD (Keane, Scott, Chavoya, Lamparaski, & Fairbanks, 1985; King, Taft, King, Hammond, & Stone, 2006). In fact, the more severe the PTSD, the more they lose relationships with nonveteran acquaintances (Laffaye, Cavella, Drescher, & Rosen, 2008).

Ironically, most scholars agree that one must process thoughts and feelings about traumatic events with others in order to overcome the impact of the event (e.g., Foa & Kozak, 1986; Lepore, Silver, Wortman, & Wayment, 1996). However, the response from the listener is very important. When someone shares about trauma and receives negative reactions to the sharing from others, they are more likely to continue to have severe symptoms of PTSD (Ullman, 2003), as well as other psychological and physical difficulties (Ullman, 2003; Ullman & Filipas, 2001). Thus, the role of the family and friends in supporting each other following stressful events is very important.

Identifying and Sharing Emotions

In earlier steps, family members began to share their needs and wants with one another. These earlier steps can give you an indication about each family member’s ability to share and trust other members of their family. In Step 4, we continue to build the family’s ability and willingness to share by delving more deeply into emotions. Many families will transition well to this stage, but some family members may be reluctant to share what they are going through or may have difficulty identifying emotions.

If family members do not feel supported by one another, they will need to develop trust in order to become resilient as a family unit. Some family members may not possess the communication skills or know how to show support toward others. Some family members prefer not to share feelings because they fear being judged or misunderstood. Some family members may have difficulty being empathetic, or they may feel uncomfortable when others are sharing their feelings. As a clinician, you may need to coach family members on how to “hear” negative emotions. Empathy is the ability to sense other’s feelings and attitudes. If families are to thrive, each member must have the capacity to listen to and accept how others feel.

Making It Real: Identifying Feelings

We begin with a simple exercise to see how willing and able each member is to identify and share feelings with each other.

Exercise Directions: Please go to Family Handout 4.1. Please have the family do the following.

- Say to the family: “__________ (say all of their names and make eye contact with each of them), many people find it uncomfortable to listen to others who are feeling negative emotions. It can be difficult to listen to someone who is suffering. Often, our first inclination is to change the subject. Sometimes we may feel compelled to try and fix the problem. Either approach can invalidate that person’s feelings.”

- Then lead a discussion around the following questions:

1. What feelings are you experiencing right now?

2. Did you experience any other feelings in the last week?

3. If someone else in your family is feeling very bad, does it make you feel uncomfortable?

4. When you feel bad, what can others around you do to support you?

Talking Points

Back to Michael and Lisa. Earlier, Lisa shared that she was feeling frustrated that Michael has not shared much about his experiences during deployment. When returnees have experienced dangerous and potentially traumatic events, it can be difficult to weed through their experiences and know what to share with their families. However, in suppressing his emotions, Michael has become less responsive to the needs of his wife, Lisa, and daughter, Abby. Michael is in a Catch-22 situation, like many other returnees. He is bearing his burdens of war, which makes him feel disconnected from his family. And his family, Lisa and Abby, sense his detachment and feel like Michael doesn’t trust them or love them the same anymore.

During this exercise, Michael denied that he was having any feelings, and he shared that his emotions had been “numb” since he returned from deployment. However, Michael also said that he feels very uncomfortable when others express sadness, fear, and other negative emotions. He said that, when he feels bad, he prefers that others “leave him alone.” Abby, on the other hand, was able to identify her feelings. She said that she was feeling “sad” at the moment and had been feeling “angry and sad” in the previous week. Like her father, Abby feels uncomfortable when others express negative emotions. Unlike Michael, however, she said that she would like others to “listen to her” to show their support when she feels bad. Furthermore, Lisa shared that she, too, had been feeling angry and sad. She said that she felt somewhat comfortable having others share negative emotions with her. Additionally, she said that when she shares negative emotions, she would like others to listen to her and give her a hug.

FOR YOUR INFORMATION: STIGMA ABOUT MENTAL HEALTH

Despite military-wide education programs designed to decrease stigma about mental health problems, stigma continues to prevent people from seeking appropriate care. Research shows that concerns about stigma are particularly salient for those who currently suffer from emotional problems (compared to those without problems). Active-duty, reservist, and National Guard OEF/OIF returnees who screen positive for mental health problems consistently report high levels of stigma (e.g., Hoge et al., 2004; Pietrzak et al., 2009).

Many of the stigma-related beliefs held by veterans and active-duty service members reflect concerns about discrimination by others for having mental health problems. For example, active-duty soldiers and Marines returning from Iraq or Afghanistan were concerned, should they seek mental health care, that “My unit leadership might treat me differently” (36.5%), “I would be seen as weak” (35.4%), “Members of my unit might have less confidence in me” (34.2%), or “It would harm my career” (27.0%, Hoge et al., 2004).

Additionally, emerging research shows that OEF/OIF returnees who screen positive for mental health problems have concerns about stigma. For example, recent research shows that some returnees fear that family members would have less confidence in them if they “knew” they had a mental health problem, and they would see them as weak (Whealin et al., 2011). When family members view mental health problems as a sign of weakness, such family members (and peers) may covertly and overtly discourage returnees from talking about their problems (Lorber & Garcia, 2010). In other cases, however, returnees may overestimate the amount of stigma-related beliefs that family members hold and keep symptoms to themselves. In either case, returnees experience shame or guilt for having such symptoms, which only compounds the problem.

When someone suffering from emotional problems holds stigma-related beliefs about mental health, they commonly avoid sharing negative emotions for a variety of reasons. For example, some people may equate having emotions, such as fear or sadness, with weakness. Alternatively, others may not want to burden family members with their troubles. Still others may feel that if they share their feelings, they will “lose control.” It will be important for you to take some time in the session to explore the family’s beliefs about mental health and sharing of experiences.

Helping the Family to Share

In therapy, take time to encourage family members to listen without judging others in the family, especially when they are expressing painful emotions or their fears about expressing emotions. As mentioned earlier, some returnees may have trouble identifying or sharing their emotions. Many returnees believe that expressing their feelings is a sign of weakness. In cases like this, you can emphasize that sharing emotions does not weaken a person. It can be helpful to point out that sharing emotions makes the emotions less intense.

Sharing emotions can also help connect people and make them feel less isolated from others. Reinforce that the avoidance of sharing emotions and problems usually just makes the problems worse and can lead to physical and emotional health problems. Normalize the expression of emotion and validate family members’ emotions. This can make the process of sharing easier (please see Family Handout Step 4.2).

The Problem of “Sucking it Up”

In the case of Michael, Lisa, and Abby, it was important to address Michael’s discomfort about others expressing negative emotions. Michael said that he believes that expressing sadness and other negative emotions is a sign of weakness. Earlier in our session, Michael had said he had a “suck it up” attitude; that no matter what happens, a service member should be able to “suck it up.”

With a client such as Michael, it is important to find out what he or she might be thinking when others share emotions with him or her. Michael said that when Lisa shares negative emotions with him, he feels “helpless” when she is distressed. Lisa explained to Michael that he doesn’t need to solve her problems when she is distressed. Rather, she just wants to share part of who she is with him. Last, I discussed with the family that emotions such as sadness are normal reactions to witnessing highly stressful and, at times, morally incomprehensible events. I talked about how “sucking it up” can be protective during war, but stuffing emotions is no longer adaptive once a service member returns home.

Improving Listening Skills

Some family members will have no problem attending to the needs of others in their family, but some family members will need more guidance to understand others’ points of view. Michael had mentioned that sometimes it was difficult for him to listen to others. Lisa had specifically voiced concerns that Michael does not listen to their daughter, Abby, when she is feeling upset. You may need to help a family member(s) understand that empathy is essential for healthy communication and, ultimately, for healthy relationships with those whom they love.

Making It Real: Deepening Communication

In this exercise, we get to a deeper level of communication and trust among family members. Open the exercise by addressing the various types of sharing styles that each family member has. It is ideal that family members share with each other in a conversational style during this exercise. Also, it may be necessary to help family members keep in mind that their experience may be very different from that of others in their family. It is vital for family members to value others’ right to their feelings and opinions. Even if a family member cannot relate to another family member’s feelings and/or opinions, he or she should still be guided to respect their opinions.

Exercise Directions: Please go to Family Handout Step 4.3.

- In this exercise, we follow up on the feelings that were expressed earlier. Guide the family to share more about how they are feeling. You may start out by saying:

- “I would like you to share more about the feelings you expressed earlier. However, when one person shares, it’s important for the other family members not to interrupt, but just to listen. We can use the stress ball as a reminder that one person has the floor. Here are some guidelines for listening to others when they are expressing how they feel:

1. First, take time to provide the person with your full attention.

2. When your family member shares, just listen. Focus on what the other person is communicating. Do not interrupt or think about what you want to say next. Try to put aside any need to rescue the person.

3. Simply let the person know that you support them and are there for them by nodding or encouraging them to share more.

4. Last, ask the person if there is anything you can do to help.

Talking Points

This exercise was a good opportunity for Michael to practice his listening skills. In our previous session, we had identified his need to begin to communicate more effectively with his daughter, Abby. Here is how things went for our family.

THERAPIST: Who would like to go first?

MICHAEL: Abby, I’d like to know why you feel sad and angry.

ABBY: You don’t even want to be my father.

MICHAEL: That’s not true, Abby. (sounding calm but surprised at this bit of information) Where did you get that idea?

THERAPIST: Michael, remember that your role is to listen and support how Abby feels.

MICHAEL: I’m sorry, Abby, I’d like to hear more about why you think I don’t want to be your father.

ABBY: Well, you never want to be with me. When I showed you the mug I made for you last week, you didn’t even look at it!

MICHAEL: Is there anything else?

ABBY: When I won the school spelling bee last winter, you didn’t even say anything!

MICHAEL: What can I do to help you, Abby?

ABBY (earnestly): I don’t know. I guess I just want you to listen to me.

MICHAEL (gets down on his knees next to Abby): Abby, I had no idea. . . . Daddy’s just . . . Daddy’s just not feeling well right now. It has nothing to do with you. I will do my best to listen to you.

After all members of the family have had a chance to share and listen, please open it up for further sharing on a feeling level. The goal here is to stay at the heart level—at the emotions.

THERAPIST: Lisa, Michael, Abby, let’s take some time to open the floor, for each of you to share with each other how you are feeling. (Pause) Michael, would you like to share your reactions first?

MICHAEL: Well, first I want to say that I am proud of the accomplishments that Abby and Lisa have made in the last year. I know it wasn’t easy with me being so isolated. I didn’t know that Abby was angry. I feel like a shit.

Lisa and Abby seem to not know what to say, so after a moment, I jump in.

THERAPIST: Tell us more.

MICHAEL: Well, I feel so ashamed. I cannot support you two anymore. I feel like a failure as a husband and father. I let down Frank (the private who was killed during an attack) and I let down you.

LISA: Anything else?

MICHAEL: I guess I’ve been feeling sad. I haven’t been able to push through it. I’ve been feeling sad and that’s why I’ve pushed you two away.

Because Michael seems finished with his sharing, I nod to Lisa.

LISA: What would you like from us?

MICHAEL (puts his head in his hands then looks at each of them): I would like you to forgive me for letting you down.

LISA: I never felt that you let me down, Michael. I am so proud of you. I am proud to be your wife. Thank you so much for sharing how you feel with me.

ABBY: I’m proud of you, Dad. I think I have the strongest Dad in the world.

How the Ice Got Broken

This last exercise broke the ice for Michael. Up to this point, he had not been able to shed his military identity to even recognize the sadness that he was experiencing. With some extra support, Michael was able to share a little about the attack he experienced when his truck encountered an IED. He told us that, although he was hurt himself, it was even more difficult for him to see Frank, the private who worked for him, get seriously injured. He said that he still thinks about the event. Sharing his experience (even without the gory details) provided Michael with emotional support and helped his family to know that they are important enough to share this part of his life with them.

This exercise helped bridge the gap that was keeping this family detached from one another. The key to healing the military family is to enable family members to risk being vulnerable by sharing, to focus and hone in on each other’s strengths, and to help family members begin to build each other up.

As a result of all of the adjustments in the family, military children are often affected. When roles and responsibilities change, with one parent coming and going from the family, it can create a confusing situation for some children. So, many military children try to test their parent (returnee) to see if they can get their way now. As in any family, children can act out. However, beyond this, in military families, children lose one of their parents to deployment, sometimes for long periods. Without very clear boundaries in place, children can act out badly and take advantage of the changes in the family structure to get what they want.

Setting Boundaries

Boundary setting is crucial for reestablishing the balance in the military family. One of the main components of family resilience is to have clear rules governing the family’s hierarchy (Haley, 2007). Many returnees feel unable to relate to their children (Gottman, Gottman, & Atkins, 2011). Others who are physically or emotionally disabled may develop a pattern of letting the other parent make all of the decisions. In this case, you can help the returnee to step back into the parent role and to define a clear family hierarchy. A first step is to rebuild a “strong parental coalition” between parents.

In the case of Lisa and Michael, both parents have to be and stay in charge. The parent who has been away on deployment may need to learn to take their position back in the parental role. Many returning service members feel guilty for missing parts of their children’s lives, and there may be times when they cave in to their kids’ requests to get back into their good graces. You can reinforce that being away on deployments does not forfeit their parenting rights. Assert that the best way to help their children adjust is to set boundaries and stick to them. This can be accomplished by having the parents ease back into making decisions together.

Bonding Activities

Michael has struggled with having physical and psychological injuries, and this has left him feeling out of sync with his family. His daughter, Abby, has also been feeling disconnected from her father. One way to help them reconnect is by giving them ways to bond again.

Using Behavior Modification on Adults Too

Behavior modification is often associated with helping children behave better. However, it can also help adults to incorporate more positive behaviors into their lives. In addition, we can use behavior modification to help military parents rebond with their children.

The How-To of Behavior Modification

Behavior modification techniques help clients directly alter their behavior in order to minimize unhealthy coping behavior—such as watching TV for 5 hours a day—and maximize healthy behavior—such as exercising or spending time with children. An effective behavior modification method is to pair a new, healthy coping behavior with a behavior the client already does on a regular basis. The activity a person does on a regular basis serves as reinforcement, thus making them more likely to implement the new coping behavior.

For example, Greg, a young Air Force Airman who recently returned from Afghanistan, was spending most of his time playing video games in the evening. His 18-year-old fiancé, Beth, felt ignored and unappreciated by Greg. In session, I negotiated with Greg to spend at least an hour with Beth per night doing something together as a couple. Together, Greg and Beth came up with activities they both could enjoy, such as playing cards, going to the gym, or watching a TV show. Once he did this, Greg could “reward” himself by playing video games. Soon, the new coping activities and couple time became habit. Behavior modification can help an individual and the family’s ability to develop and maintain adaptive coping.

Making Time for Family Time

Time that the family spends together does not “just happen” (Stinnett, 1979). Resilient families make time together happen by scheduling it into their lives. To reinforce the family hierarchy and parental coalition, Michael and Lisa need to start doing things as a family, rather than simply accommodating Michael’s isolation. Similarly, Michael should now be pushed to expand his activities, so that his isolating does not become a pattern. However, it is important to make changes gradually, so that the family has a higher likelihood for success when trying their new activities together. Here’s how family time was negotiated in session with Michael and Lisa.

THERAPIST: Michael, your coping habits, watching TV, spending time with your buddies, works for you now. However, it’s very important to begin to push yourself a little to pick up more of the habits you had before you deployed. Do you remember how you felt before deployment?

MICHAEL: Yeah, I had a lot more energy, and also a lot more patience. I used to spend a lot more time with Lisa and Abby, and to do things like work around the house and in the yard.

THERAPIST: Has your pain made it more difficult to work around the house and in the yard?

MICHAEL: Yeah, I try to ignore the pain, but I guess it is one reason why I don’t enjoy working in the yard anymore.

THERAPIST: What might be important for you then is to find a new activity that you do enjoy, that helps get your mind off your pain, while you also enjoy time with your family.

MICHAEL: Well, in my pain management program, they recommended that I begin building models again. That’s something I did when I was a kid.

THERAPIST: Okay, great idea, Michael. Maybe you can consider putting a model together with Abby, so that you can spend some quality time together. What do you think about that?

MICHAEL: Yeah, we can try that. I think she’d enjoy it too. A bonding activity. That’s good.

Family rituals are basically a regular bonding activity that family members do together. In the case of Michael and Abby, they would begin to share some usual, quality time putting models together. Rituals can be as simple as this family’s repeated activities, or they can be more complicated for very special, marked occasions.

What Is a Ritual?

A ritual is a symbolic form of communication that is performed systematically over time. Rituals can help families bond and grow closer together. Rituals can help establish, clarify, and stabilize via expected roles, boundaries, and rules so that all members know that “this is the way our family is” (Wolin & Bennett, 1984, p. 401). Rituals can help facilitate change or transition, while maintaining order.

FOR YOUR INFORMATION: FAMILY RITUALS FOR TODAY’S FAMILIES

Family celebrations include the ways a family celebrates annual events (Christmas, Passover, Thanksgiving, etc.) or rites of passage (weddings, baptisms, bar mitzvahs, etc.). The celebration involves the rituals, which affirm or honor that particular occasion. Celebrations may include family traditions, special food and drink, and gifts. Celebrations help define the family, as well as mark the family’s development phase (Wolin & Bennett, 1984, p. 404).

Families today, compared to those in the past, rarely connect with a family story. Piecing together the story(ies) of family members to other members of the family can help create cohesion and a sense of stability. Even when all family members are not explicitly a part of the family story, they benefit from knowing about and participating in the telling of the story. Here are some examples of content areas that help families create a common story:

- How grandpa and grandma came to the United States

- How Mom and Dad met

- How Mom and Dad got engaged

- What Mom and/or Dad did on their deployment

- How Dad came home from deployment when junior was born

- How the family celebrated when Dad came home from deployment

- How big brother took care of his little sister when Mom was deployed

Robert and Felicia’s Family Rituals

Robert and Felicia are the career soldiers we introduced in Step 3. During Robert’s last deployment, the couple’s two boys, ages 10 and 13, had begun defying Felicia’s authority, leading her to act out and actually push their young son, Robbie. When Robert returned from deployment, the boys continued to be defiant and have outbursts of anger. Although Felicia had made significant progress in dealing with her stress, the boys seemed to continue to act out when they felt stressed. In the past month, the older brother, John, had been suspended from school for cutting classes with his friends. Family dinners were a particular issue. In our session, we recognized that dinners had become an opportunity for Felicia to criticize the boys. Often, peaceful dinners only took place when the TV was turned on.

The dysfunction in this family had become a pattern that would take time and effort to overcome. With exploration, we identified that the boys felt resented and resentful. It became clear that, because of the family’s lack of communication, John and Robbie were not getting the guidance they needed to help them cope with their stress and navigate life choices.

Talking Points

In our session, Robert and Felicia became aware that the boys needed more structure, as well as guidance and affirmation from both of them. As a family, they decided to begin a ritual—their family would eat dinner together every night, without TV. During dinner, the parents asked their sons about what they had learned in school that day and listened to various aspects of their daily experiences. This discussion allowed Robert and Felicia to learn more about the challenges the boys were facing.

By managing her stress, Felicia was able to refrain from criticizing the boys. Instead, she used the time to help the boys explore ways that they could solve problems. Importantly, both parents focused on finding an opportunity to praise their sons for making positive choices. Robert was planning to continue this ritual during Felicia’s upcoming deployment, thus providing an element of stability and order in the family.

Shifts in roles and responsibilities between partners are common with repeated deployments. However, a family can flexibly adapt to those changes. Families can learn to communicate what they are experiencing and feeling. They can support each other and build each other up. They can spend time together as a unit and create or continue family rituals. Additionally, family members can use reactive coping when their problems or anger become overwhelming. All of these positive efforts will lead to a family that not only has the parents being parents again but that also becomes a more bonded, closer family unit—and that means healing for the military family.

- Sharing emotions helps connect people with others, and so can help people feel less isolated from others.

- Sharing emotions is associated with better physical and emotional health.

- Families can learn to communicate what they are experiencing and feeling.

- It is important for family members to learn to listen to one another and validate each other’s feelings.

- Families can spend time together as a unit and create or continue family rituals.

Taking Action

Taking action will help rebuild the family. Please check off each step as the family accomplishes it.

- The family should practice identifying and expressing their feelings to one another this week.

- During family time this week, family members should take turns asking questions about the others’ week, how it was for them, and how they felt about different things that happened. Family members should practice listening and validating each other.

- The family should come up with a family ritual together, which they can do together this week.