In 1998 the formidable Mrs Gwynneth Dunwoody, Member of Parliament for Crewe and Nantwich, introduced a question in the House of Commons, in London, which was reported in the very serious official Government journal, Hansard. ‘What plans has the Culture Secretary for the repatriation of Winnie-the-Pooh?’

It seems he had none.

Mrs Dunwoody had met Pooh and the other animals on a visit to New York and thought they looked very sad. Like the Elgin Marbles, she declared, they should be in their original home. So she organised a petition.

Tony Blair and President Clinton were locked in discussion over the possibility of war in Iraq and the Global Economy at the time. unsurprisingly, in reply to questions when Mr Blair appeared on ABC’s Good Morning America, he said that Winnie-the-Pooh was ‘down the agenda’. The White House issued a statement declaring that the subject was not expected either to be on the formal agenda for the President’s meeting with Mr Blair but that it might come up in informal conversation.

Newspapers in both countries covered the confrontation with banner headlines ‘Free the Hartfield Five!’ they protested in Britain. ‘Pooh on You’ and ‘Brits Ignite a Poo-Haha’ replied the New York Times .

Mayor Rudolph Guiliani made an emergency visit to the Donnell Children’s Room and issued a statement. ‘Like millions of other immigrants, Winnie-the-Pooh and his friends came to America to build a better life for themselves and they want to remain in the Capital of the World.’ He said that he had personally assured Pooh that he should not be bothered by the British Parliamentarian who was demanding his return.

So that was that and Pooh remained an American citizen.

He had outlived most of those who had been his friends and family.

Anne (Darlington/Ryde) died in 1958. Blue and Moon and she had been lifelong friends, writing often. Milne himself saved first editions for her and wrote lengthy doggerel verses in them, signed Blue. A copy of his 1950 book of short stories A Table Near the Band, is signed with ‘25 years’ love’.

Her daughters, Julia and Katie, treasure especially the heartrending sadness of Moon’s own letter to their grandparents when Anne died at the age of only thirty-eight:

‘Dear Bill and Marjorie,

I learnt this morning of Anne’s death. It is almost as though a sister had died.She was so very close to me when we were children and she has remained close to my family ever since. I think she possessed more kindness and sympathy than anyone I have ever known.’

Remember my affection and admiration for dear Anne, but don’t write back, please.’

Moon.

Daphne Milne died, almost unnoticed in London on 22 March 1971.

Elliott Graham, Winnie-the-Pooh’s devoted guardian, died in 1988. He was in his 83rd year. His charge of forty years was, by then, safely secure in New York Children’s Library.

Christopher Robin Milne died in 1996. For almost half-a-century he had lived a happy, book-lined, life with his wife, Lesley and their daughter Clare, in the Harbour Bookshop, Dartmouth, Devon. His father’s biographer, Ann Thwaite, wrote an obituary for The Times in which she said: ‘Christopher Milne was a remarkable man who triumphantly survived a remarkable childhood, though not without considerable pain on the way.’

Finally he escaped the shadows of the past and his three autobiographies The Enchanted Places, The Path Through the Trees and Hollow on the Hill, offer his readers a rare glimpse of a very private, yet inescapably public man and his passion for the countryside, learned all those years ago as a little boy with his teddy bear in Hartfield. He had proved, as Eeyore had claimed, ‘this writing business’ is not ‘all stuff and nonsense.’ He could do it, too.

Peter Dennis, Pooh’s Ambassador Extraordinary, died in 2009. He had adopted a characteristically courageous, death-defying, attitude to the end, throwing himself into work and life. His last gift to the bear to whom he had devoted so much of his professional life, was a set of recordings of his friend Christopher Milne’s autobiographies.

Shepard died in 1976. Many years before, A.A. Milne has written a poem which included the words “when I am gone, let Shepard decorate my tomb”: Shepard was never invited to fulfil these wishes and it is rather sad that his own grave bears the drawings not of Pooh and Piglet but of those other much loved characters, Mole and Ratty.

For A.A. Milne himself there seems to have been no funeral when he died in 1956: there was the rather surprising memorial service for a man who was an atheist, but no recollection among family or friends of what Daphne did with her husband’s remains. The Dictionary of National Biography says he was cremated at Tunbridge Wells: but this is impossible since the Crematorium was not opened until 1959. This launched us on extensive but fruitless investigations around archives in Kent, Sussex and London. As our quest for Pooh’s story was coming to an end, researcher Sally Evemy decided to double check several cemeteries and crematoria. When she telephoned the Downs Crematorium in Brighton they again found there was nothing ‘on the system’. But probing their paper records produced an astonishing revelation.

The Downs is situated high above Brighton looking out towards the English Channel. It was to here, on 3rd February – a bitterly cold winter’s day, on which the East Grinstead Courier headlined ‘Arctic Spell Hits Road and Rail Traffic’ – that the remains of the genius, A.A. Milne, were driven across Ashdown Forest towards Brighton an hour away. There is no suggestion of a funeral, or of any mourners present. The Crematorium staff say that his ashes were scattered over the upper Memorial Garden.

Today the only memorials to the author who created one of literature’s great immortals are the blue plaque on his home in Chelsea, that overlooking the slopes of Ashdown Forest and perhaps, most important of all – the elderly British-born teddy bear who inspired him.

In England, there is to be a new web-site appeal for recognition of the inspiration that Pooh’s life and thoughts have been to so many and the immense contribution his commercial acumen has made to the welfare of the disabled and deprived.

The problem is, where and what should that memorial be? A statue? A blue plaque? A museum? Could The Elms in Acton where it all began be the ideal setting? Or would the Conservators of Ashdown Forest, perhaps, now welcome the publicity?

Whatever is decided, whatever happens on the way, the real Winnie-the-Pooh sits safely in his air-conditioned American retirement home welcoming homage from far and wide. Far away across the Atlantic, in Sussex, pilgrims from around the world still follow in his footsteps to the Enchanted Place on top of the Forest, where as A.A. Milne promised all those years ago ‘a little boy and his bear would always be playing.’

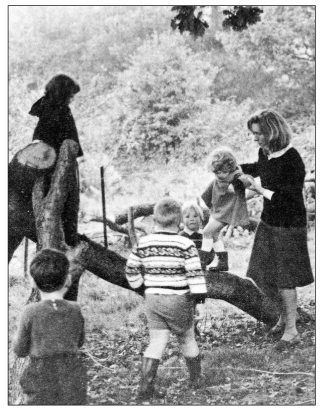

Waiting for Pooh – Shirley Harrison with Hartfield playgroup children.

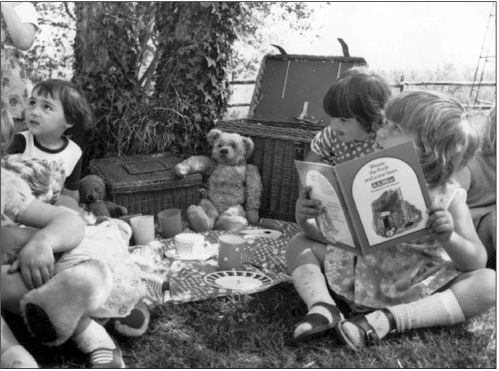

Story time with Winnie-the-Pooh and Hartfield playgroup children. (c. Mike Champion)

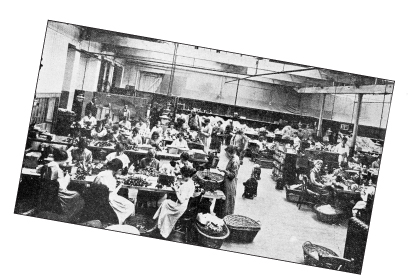

Teddies galore! The Farnell factory in the grounds of The Elms in Acton, where Pooh was ‘born.’ (The Toy and Fancy Goods Trader)

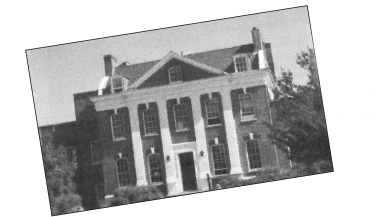

The Elms - the Farnell family home, now Twyford Church of England High School.

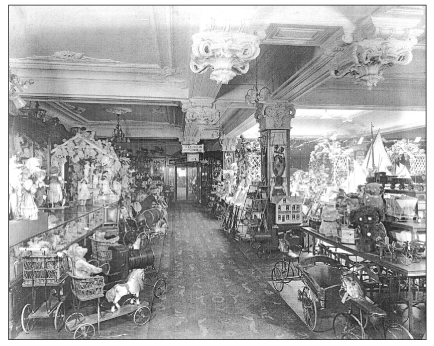

Harrods toy department in 1921 – as Pooh knew it. (c. Harrods)

Mallord Street, Chelsea –Pooh’s first home.

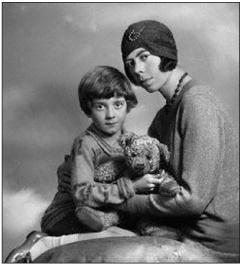

Daff with Moon and Pooh. (c. Marcus Adams, Camera Press)

Nanny Nou in retirement. (The Pitt-Payne family)

Moon, Blue and Pooh. (Source unknown)

Lieutenant Colebourn with the bear cub Winnie, who came from Canada to live – and play with Christopher Robin – in London Zoo. (Gord Crossley of the Fort Garry HorseMuseum, Winnipeg)

London walks. Anne Darlington and Christopher Robin. (Dr Katie Ryde –Anne’s daughter)

The Orangery at Plas Brondanw, Wales – where A.A. Milne started to write When We Were Very Young. (Robin Llewellyn, Portmeirion)

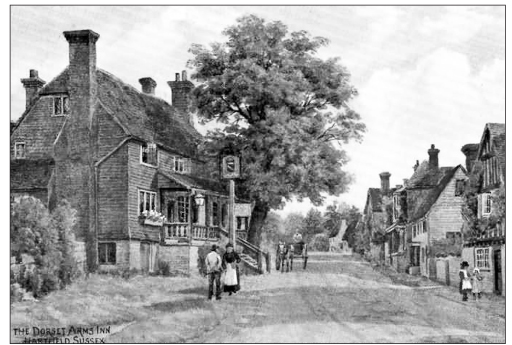

Painting of Hartfield as Pooh knew it.

Welcome to Hartfield! The village sign. (Alex Harrison)

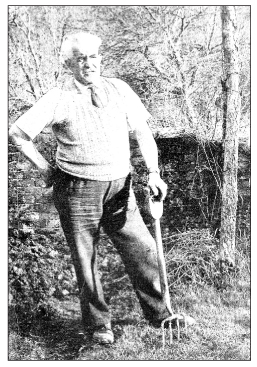

George Tasker, the gardener who created he gardens. (Peter Tasker, his son)

Christopher Robin’s playmate, Hannah Symons, who lived in Cotchford Lane. (Tim Rooth, her son)

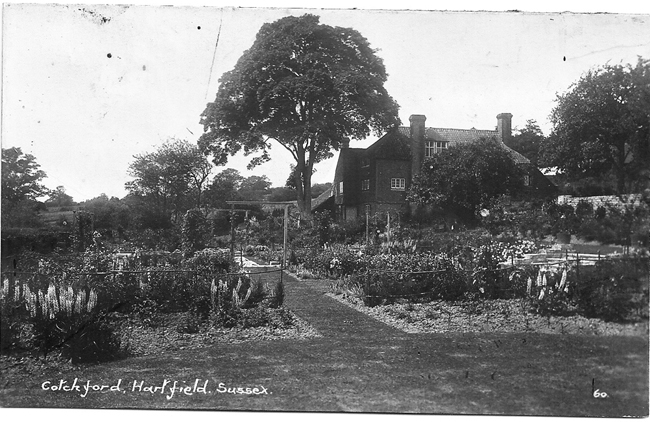

The gardens at Cotchford Farm just after the Milnes moved in. (Peter Old)

Cotchford Farm – much the same today as in 1924 when it was home to Pooh. (Alastair Johns)

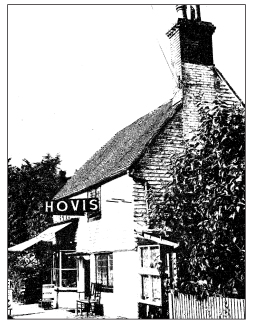

Mrs Jacques ’ bakery – where Christopher Robin bought his bullseyes. (Dawn Boakes, Mrs Jacques’ grand-daughter)

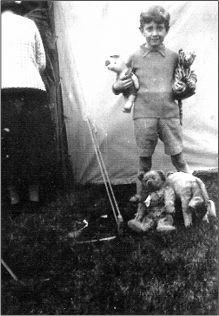

Christopher Robin in 1929 at the Pageant of Ashdown Forest with the animals. (Trevor Trench, Michael Hall School, Forest Row)

Posingford Bridge in 1907 – before it became Pooh Bridge – with the men who made it. (Mike Parcell )

Schooldays. Moon and Anne start school. (Dr. Katie Ryde, Anne’s daughter)

On Ashdown Forest - where Piglet learned to jump. (Alex Harrison)

Inside Gills Lap – Pooh’s Enchanted Place. (Mike Ridley)

The grown ups who, as children, took part in the Pageant of Ashdown Forest. (Angus Beaton)

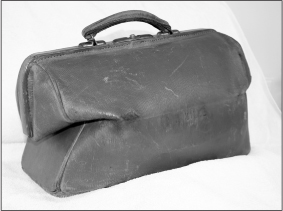

Christopher Robin’s first-ever grown-up school bag with his initials inscribed. Given by Mrs Milne to Bill Belton, Mr Rabbit Man. (Alex Harrison)

Pooh and friends – Eeyore, Kanga, Piglet and Tigger – at home in the New York Children’s Library. (c. New York Public Library – NYPL)

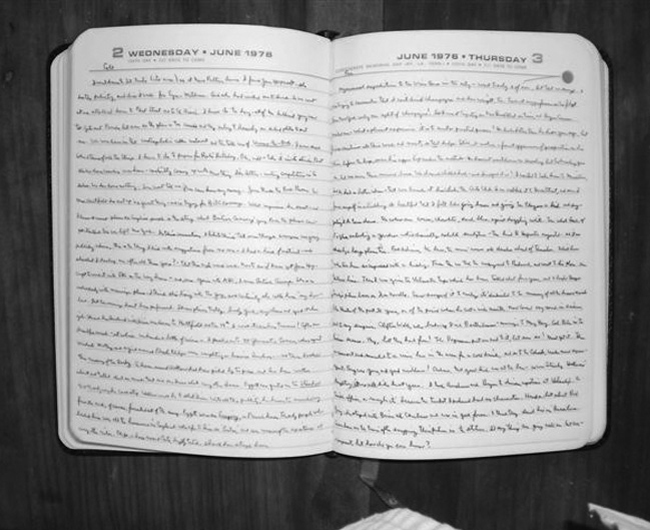

The Elliott Graham diaries. (photo Duncan Field)

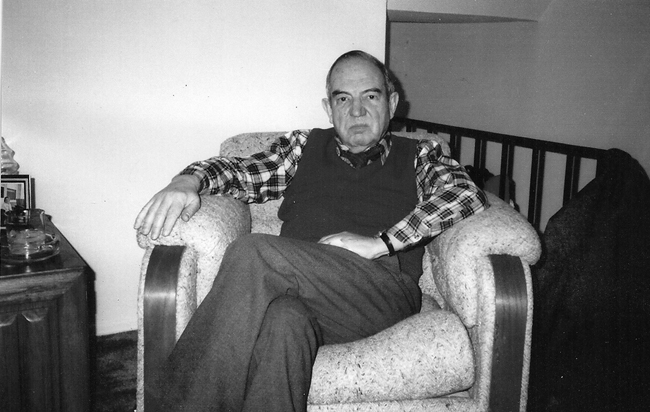

Elliott Graham, who looked after Pooh for 40 years. (Judy Henry, his niece)

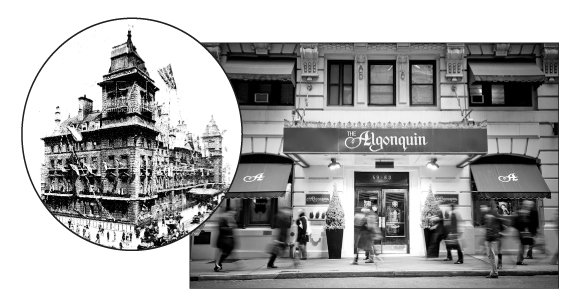

Pooh and Elliott’s favourite hotels - the Great Western Royal in Paddington (c. Steam Museum of the GWR) and the Algonquin in New York.

In 1976 Pooh returns to the Ashdown Forest to play Poohsticks with Peter Taylor from the Hartfield Playschool. (c. Mike Champion)

Pooh witnesses the engagement of a young couple at the New York Children’s Library. (photo John Peters)

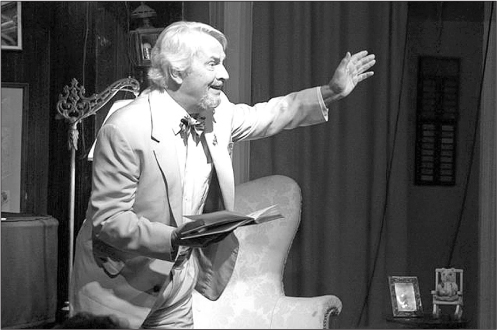

The late Peter Dennis, the actor who took his performance of Oh Bother to the United States and Britain. (Diane Dennis)

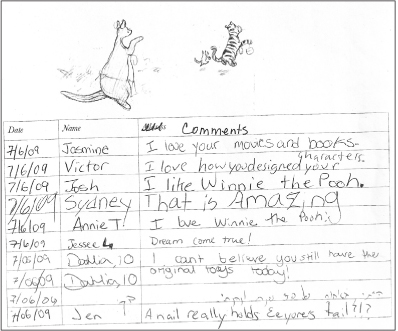

Children sign the visitors’ book in the Library.

Pooh accompanied on his travels by American author, Nancy Winters, and her own bear, Moreton Hampstead. (c. Nancy Winters)

The old bakery today -now Pooh Corner and visited by thousands of tourists from all over the world every year. (Mike Ridley)

Times have changed! The signpost to Pooh Bridge. (Shirley Harrison)

Christopher Milne’s daughter, Clare, launches a boat named after her at the Echo Centre for the Handicapped, Cornwall. (c. The Echo Centre, Liskeard)

The World Poohsticks Championships, Oxford.

The Downs Crematorium in Brighton: the Upper Memorial Garden where A.A. Milne’s ashes are now known to have been scattered. There is no plaque to commemorate his cremation.

Newly discovered entries from the Downs Crematorium ledgers: cremation number 21667 on 3rd February 1956.

|

|

Names and addresses of persons signing certificates: Doctors Hardy and Steel. |

Name of deceased: Alan Alexander Milne. |

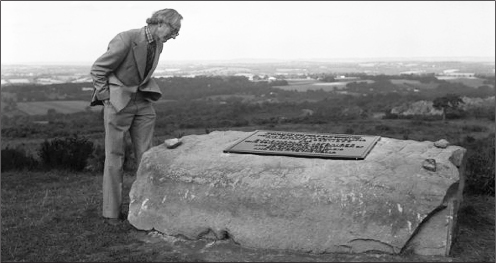

Christopher Milne stands alone, overlooking the Forest of his childhood and the plaque unveiled in honour of his father, E.H. Shepard and Winnie-the-Pooh. (c. Mike Champion)

The end of the story. Growing up – Christopher Robin off to school, kicking Pooh out of his life. (c. Punch Library)