- EPIC BIKE RIDES OF THE WORLD -

CUBA’S SOUTHERN ROLLERCOASTER

Pounded by surf, overshadowed by mountains and deeply imbued with revolutionary history, this lonely ride along Cuba’s Caribbean coast pulsates with natural and historical drama.

Cuba is full of dichotomies and its roads are no exception. Take Carretera N20 for instance, the 106 miles (170km) of potholed asphalt that runs along the south coast between Santiago de Cuba and the rustic village of Marea del Portillo, a spectacularly battered thoroughfare that could quite conceivably be described as the nation’s best and worst highway. Shielded by purple-hued mountains that tumble down to meet the iridescent Caribbean, it scores ten-out-of-ten for craggy magnificence. But, lashed by hurricanes and beset by a severe lack of maintenance, it can be purgatory for aspiring drivers. Not surprisingly, few cars attempt it, leaving the road the preserve of goats, vaqueros (cowboys) and the odd two-wheeled adventurer on a bicycle.

During nearly 20 years of travel in Cuba, I have traversed this epic highway in numerous ways, most notoriously on a protracted hitchhiking trip involving at least a dozen changes of vehicle, from a terminally ill Fiat Uno to a truck where the only other passenger was a dead pig. But my preference, if time and weather allows, is to tackle it on a bicycle. As visceral experiences go, this is Cuba as its most candid. The salty air, hidden coves, and erstwhile revolutionary history conspire to form a proverbial Columbian voyage of discovery that becomes more magical the further you pedal.

Fidel Castro and his band of bearded guerrillas lived as fugitives in these mountains for over two years in the late 1950s and the sense of eerie isolation prevails. Indeed, so deserted is the road that, in the handful of bucolic hamlets en route, farmers use it to air-dry their coffee beans, kids hijack it for baseball games, and cows parade boldly down the middle of the sun-bleached thoroughfare as if the motor car had never been invented.

Base camp for anyone attempting the ride is Santiago de Cuba, the nation’s second largest city and, in many respects, its cultural capital. Heading west from here, the journey is best split into three stages. While route-finding is easy, the ups and downs of the highway as it curls around numerous headlands present a significant physical challenge. Be prepared. Roadside facilities range from scant to non-existent.

© Jeremy Woodhouse | Getty Images

a rural church in Santiago de Cuba

The first time I ventured out on a borrowed bike, I carried inadequate provisions and ended up knocking on the doors of isolated rural homesteads to ‘beg’ for water. Sure, I met some very obliging campesinos (country dwellers) offering liquid refreshment (including rum!), but the head-lightening effects of the dehydration probably weren’t worth it. To avoid a similar fate, arm yourself with a robust bike and carry plenty of food and water.

The first recently repaired section from Santiago to the small town of Chivirico sees a modest trickle of traffic. Look out for growling camiones particulares, the noisy trucks that act as public transport in these parts. Around Chivirico you might spy another unique Cuban-ism, the amarillos, government-sponsored transit officials named for their mustard yellow uniforms; their job is to stand by the side of the road and flag down passing vehicles for hitchhikers.

“This remote region has remained utterly unspoiled, a glorious ribbon of driftwood-littered beaches”

Chivirico also has one of the route’s strangest epiphanies, the Brisas Sierra Mar, an unpretentious all-inclusive hotel that springs seemingly out of nowhere 40 miles (65km) west of Santiago. Treat yourself: there is precious little accommodation for the next 62 miles (100km).

CLIMBING PICO TURQUINO

Cuba’s highest mountain, Pico Turquino (1974m), is regularly climbed from Hwy 20, starting from a trailhead at Las Cuevas just west of El Uvero. It’s a steep and gruelling 10-hour grunt to the top and back, but no specific mountaineering skills are required. The ascent must be made with a guide, but can be split over two days with a night spent in a basic mountain shelter.

West of Chivirico, traffic dwindles to virtually nothing, while the eroded state of the road can make the going ponderous, even for cyclists. Fortunately, the magnificence of the scenery makes slow travel highly desirable.

This remote southeastern region has remained utterly unspoiled, a glorious ribbon of driftwood-littered beaches and crashing surf backed by Cuba’s two highest peaks, Turquino (1974m) and Bayamesa (1602m). Such settlements that exist are tiny and etched in revolutionary folklore. El Uvero at the 60 mile (97km) point has a monument guarded by two rows of royal palms commemorating a battle audaciously won by Castro’s rebels in 1957. Further west, La Plata, the site of another successful guerrilla attack, maintains a tiny museum. Just off the coast, vestiges of an earlier war lie underwater in the wreck of Cristóbal Colón, a Spanish destroyer sunk in the 1898 Spanish-American war. Today it’s a chillingly atmospheric dive site.

By now the steep headlands and tropical temperatures will have turned your legs the consistency of overcooked spaghetti. La Mula, around 6 miles (10km) west of El Uvero, is a rustic campismo with basic bungalows where you can recuperate just metres from the ocean.

On day three as the road crosses from Santiago de Cuba province into Granma, I like to pull over at one of the wild, Robinson Crusoe-like beaches and admire the increasingly dry terrain. Dwarf foliage including cacti is common, a result of the rain shadow effect of the Sierra Maestra. Aside from sporadic ramshackle villages, civilisation is confined to occasional bohios (thatched huts) dotting the mountain foothills. Sometimes, you’ll inexplicably spy a lone sombrero-wearing local pacing alongside the roadside, miles from anywhere, clutching a machete.

The tiny fishing village of Marea del Portillo is equipped with two low-key resorts that guard a glowering dark-sand beach framed by broccoli-green peaks. Don’t be deceived by the home-comforts. You’ve just arrived in one of the most cut-off corners of Cuba. To the north, crenelated mountain ridges shrug off clusters of bruised clouds. To the west sits Desembarco del Granma National Park, famed for its ecologically rich marine terraces. For me, this is paradise personified, a chance to resuscitate my bike-legs, carb-load at the hotel buffet and go off into the wilderness to explore some more. BS

TOOLKIT

Start // Santiago de Cuba

End // Marea del Portillo

Distance // 106 miles (170km) along a rutted but easy-to-follow road.

Getting there // The nearest airport is Aeropuerto Antonio Maceo, 4 miles (6km) south of Santiago de Cuba. From here there are daily flights to Havana, and direct flights to Canada.

Bike hire // This is rare and unreliable in Cuba. Most serious cyclists bring their own bikes with them.

Where to stay // Club Amigo Marea del Portillo (+53 23-59-70-08; www.hotelescubanacan.com); Campismo La Mula (+53 22-32-62-62; www.campismopopular.cu); Brisas Sierra Mar (+53 22-32-91-10; www.hotelescubanacan.com)

When to ride // The best time is mid-November to late-March. However, the road is prone to flooding and closures. Check ahead in Santiago.

© Pierre Logwin | Alamy

a coast road in the Sierra Maestra

- EPIC BIKE RIDES OF THE WORLD -

MORE LIKE THIS

CUBAN RIDES

LA FAROLA

Hailed as one of the seven modern engineering marvels of Cuba, La Farola (the lighthouse road) links the beach hamlet of Cajobabo on the arid Caribbean coast with the nation’s beguiling oldest city, Baracoa. Measuring 34 miles (55km) in length, the road traverses the steep-sided Sierra del Puril, snaking its way precipitously through a landscape of granite cliffs and pine-scented cloud forest before falling, with eerie suddenness, upon the lush tropical paradise of the Atlantic coastline. For cyclists, it offers a classic Tour de France-style challenge with tough climbs, invigorating descents and relatively smooth roads. La Farola starts 124 miles (200km) east of Santiago de Cuba and is thus best incorporated into a wider Cuban cycling excursion. You could also charter a taxi to drop you off at the start point.

Start // Cajobabo

End // Baracoa

Distance // 34 miles (55km)

GUADALAVACA TO BANES

Talk to savvy repeat visitors in Guadalavaca’s popular resort strip and you’ll discover that one of the region’s most epiphanic activities is to procure a bicycle and pedal it through undulating rural terrain to the fiercely traditional town of Banes 21 miles (33km) to the east. This beautifully bucolic ride transports you from the resort-heavy north coast to a gritty slice of the real Cuba in a matter of hours along a road where you’re more likely to encounter a horse and cart than a traffic jam. Some of the resorts lend out bikes but pedalling these basic machines can be hard work; in-the-know visitors often fly in with their own bikes (Holguín’s Frank País international airport receives direct flights from the UK, Canada and Italy).

Start // Guadalavaca

End // Banes

Distance // 21 miles (33km)

VALLE DE VIÑALES

Viñales is a small farming community that does a lucrative side-business in tourism. It sits nestled among craggy mogotes (steep, haystack-shaped hills) in Cuba’s primary tobacco-growing region. With about as much traffic on its roads as 1940s Britain, the region – which is protected as both a Unesco World Heritage site and National Park – is ideal for cycling. Various loops can be plotted around the valley’s multifarious sights, which include caves, tobacco plantations, climbing routes and snippets of rural Cuban life. Riders can hire from the Bike Rental Point in Viñales’ main plaza. Or your casa particular (private homestay, of which there are dozens in the village) may have bicycles available to rent.

Getting there // Viñales is easily reached from Havana by bus

Distance // Whatever you feel like

© Mark Read

a Cuban cigar roller in the Valle de Viñales

- EPIC BIKE RIDES OF THE WORLD -

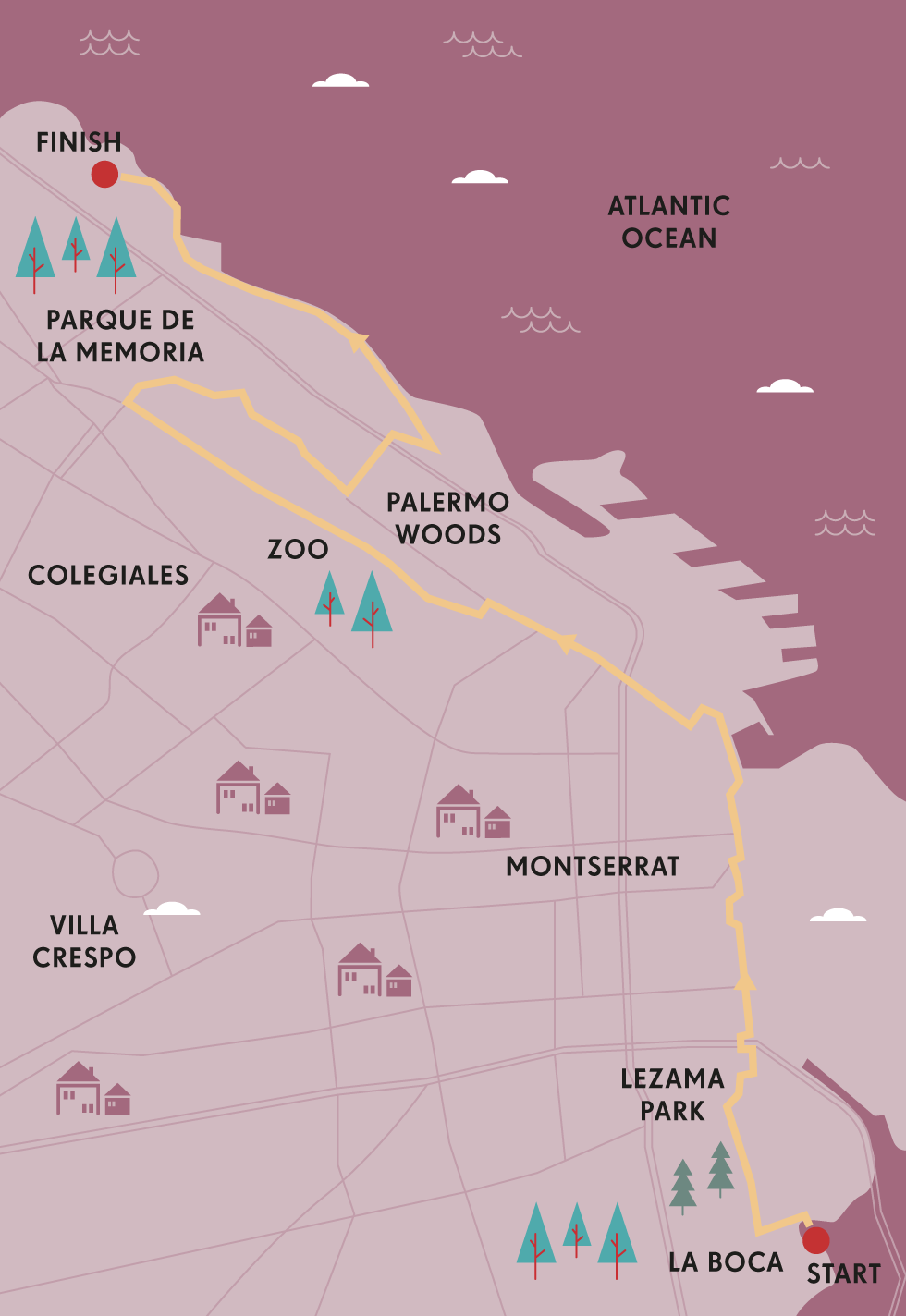

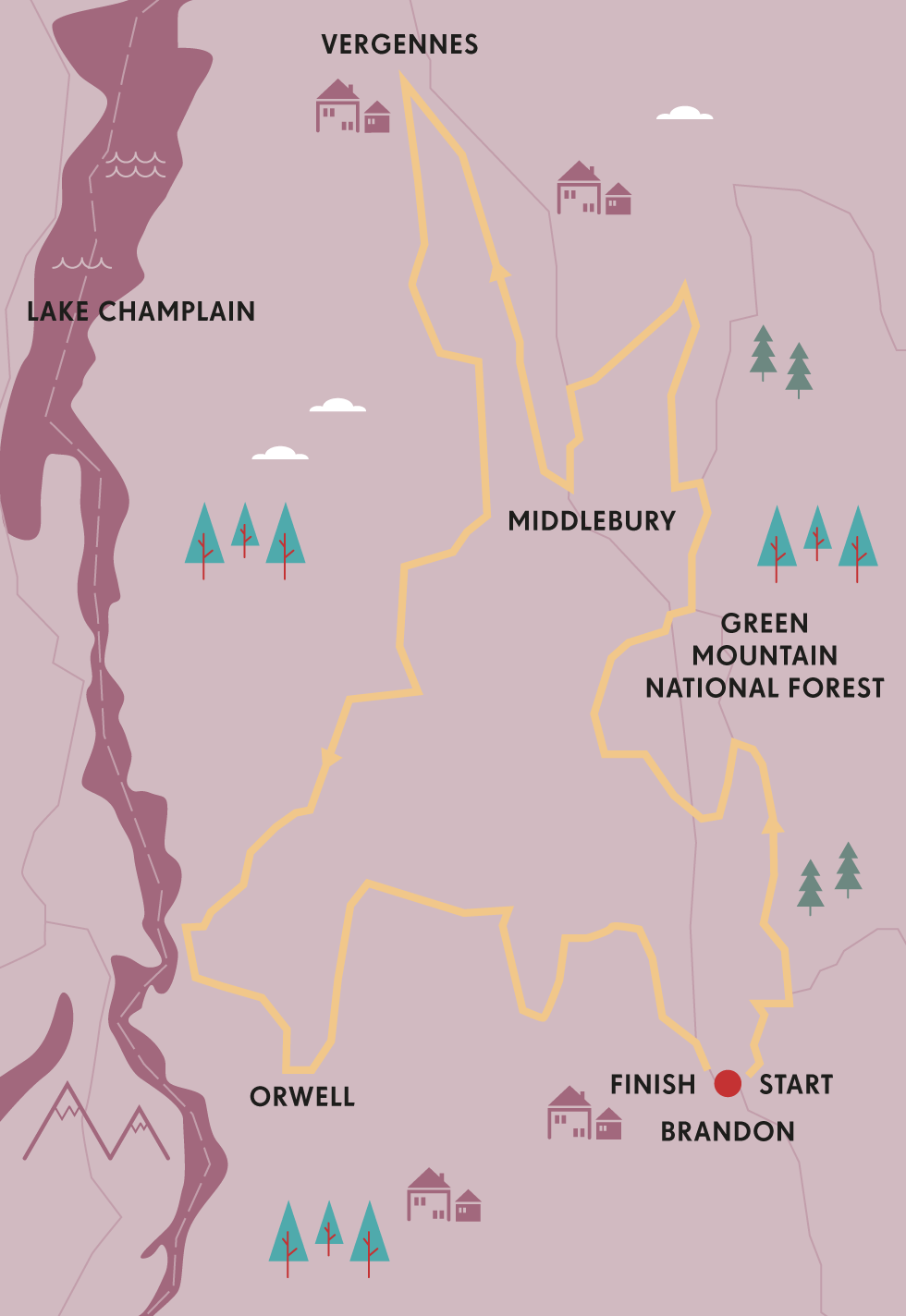

TO THE TIP OF PATAGONIA

Cyclists rub shoulders with gauchos and guanacos in southern Argentina, braving howling wind to reach the tip of the South American continent.

Out on the bolt-straight roads of the Argentinian pampa (vast plains) my handlebars stay true, but my mind wanders. The open expanse of Southern Patagonia is a pensive place, a vast and empty land that stirs memories and emotion, like a calling to fill its void.

As my legs spin, I hum along to the buzz of knobbly tyres on smooth asphalt. I listen to the snap of my open shirt, which flaps behind me like a cape. I try and clear my head. But like any meditation, I become stuck on certain thoughts, clanking around like coins in a washing machine. Before long, an ostrich-like rhea waddles out of the camouflage of the plains. I smile, my spirits lifted. Then, a guanaco, the camelid native to these parts, breaks rank and jumps daintily over the endless fence line I’ve been following. It makes a chuckling sound as I pass, as if remarking on the ridiculousness of my toils.

It’s a sentiment that seems to be echoed by others. Once, I see the blur of a passenger photographing me from a minivan that hurtles past. What must they be thinking? I guess I must look a little crazy, bearded and unkempt, out here in the emptiness. Later, a couple flag me down to quiz me about my bike. We talk a while by the roadside. I’ve noticed a distinct soulfulness in Argentinians, perhaps intensified by the thought-stirring sparseness of their land. ‘Que lindo este viaje,’ the man says, gesturing to his heart, and shaking my hand warmly. ‘What a beautiful journey.’

A beautiful journey indeed, and one that captures Patagonia’s contemplative character, its windswept isolation and its spectacular vistas. Indeed, the ride down from El Chaltén showcases one its finest moments; the granite silhouette of Monte Fitz Roy is the stuff of picture postcards and mountaineering legends.

© Cass Gilbert

heading into the Patagonian hills

I pedal on. As asphalt peters out, I plough my way through deep, corrugated ripio (gravel), gliding from one side to the other in search of the truest line. In this light, it’s hard to even tell what time of day it is. It could be just before sunset, but in fact it’s early afternoon. Scale plays games on the pampa, and distance takes on a different quality; perhaps a more mysterious form of measurement is appropriate, like leagues. Only roadside shrines mark the passing of time, and drainage culverts, into which cyclists sometimes burrow to escape the howling winds.

And those winds! They’re incessant. Thankfully, my southerly trajectory means they’re in my favour much of the time. But when they’re not, it’s like slamming against a steel wall. A particular tactic is thus required: strategic hops from one wind-free or rain-sheltered enclave to another. Most are abandoned buildings, skeletal husks that resonate former lives. Like hallowed secrets, the exact locations of these sanctuaries are swapped around a carton of wine at a campsite, or scrawled onto a crumpled map out on the road.

Among the most popular is the so-called Pink Hotel on Ruta 40, the legendary road that spans the entire length of this country. An abandoned complex set on a solitary stretch of pampa, the Pink Hotel has long shielded a migration of riders from the howling, tent-crushing wind that gathers with gusto each afternoon. On the night I pass through, it’s a surprisingly social premises. I’m one of five riders heading south, joined by a French-Canadian couple braving the elements north. We roll out our mats on the hotel’s parquet floor and sign the guestbook: the canvas of a graffitied wall, onto which cyclists scrawl their names and a precis of their journeys.

PENGUIN COLONIES

No visit to Patagonia is complete without an encounter with its most characterful residents. Of the two penguin colonies en route, one involves a ferry ride to Isla Magdalena, home to 60,000 pairs of Magellanic penguins. Like drunkards dressed up for a ball, they stagger around in the high winds. The other is at Parque Pingüino Rey in Bahia Inútil, where cyclists can camp near a group of majestic King Penguins that stand up to 1m tall.

Other such places of calm come and go. At a lonely outpost near Tapi Aike, Fabien the police officer ushers me in, as he has done to so many cyclists before me. He feeds me a hearty dinner, and together we watch dubbed movies late into the night. And there’s Panadería La Union, about which I hear stories months before I actually arrive. Its location is triple-ringed excitedly on my dog-eared map, and a note scrawled to the side: ‘Bakery. Delicious empanadas and cakes. Hosts cyclists for free.’

Breaking the monosyllabic mood of Southern Patagonia, there are also moments of startling eloquence. Sometimes, it’s as simple as a lenticular cloud, or a team of muscular horses watching me ride by. At other times, it’s raw geology. In El Calafate, I head out to Perito Moreno Glacier. Spanning 2.5 miles (4km) in width, the sight itself is as impressive as the sound it emits: an incessant soundtrack of gurgles and murmurs, of deep, resonant rumbles and thunderous crunches.

I ride on, away from Ruta 40, forging my way closer to the coastline, until finally I cross the Strait of Magellan to Tierra del Fuego, the Chilean and Argentinian archipelago that lies off the southernmost tip of the South American continent. It’s named after the myriad of fires once kept by the indigenous Yámana – a hardy folk who walked barefoot through snow. By now, I’m a member of my own impromptu cycling collective, pilgrims drawn from around the globe, pedalling by day and sharing stories by night.

For many, riding to the very tip of the South American continent is the end of long, arduous and undoubtedly beautiful journey; adventures that have unfolded since Colombia, Mexico or even Alaska. And now here we are. Together, we cycle through the gates of Ushuaia. Connected by a rush of similar emotions, we high-five. We hug. We look round in slight disbelief. Yes, we’ve arrived. Ahead, the road has finally run out. CG

“Together we cycle through the gates of Ushuaia. Connected by a rush of similar emotions, we high-five”

TOOLKIT

Start // El Chaltén

End // Ushuaia

Distance // 714.5 miles (1150km)

Getting there // Fly or bus into El Calafate, and out of Ushuaia.

When to ride // The best time to visit the area is during Patagonian summer – from November to March.

How to ride // Head north to south, or face a soul destroying headwind much of the way.

Where to stay // Bring a stout tent, and keep your eyes peeled for abandoned houses!

What to take // Weather can be notoriously mixed; pack plenty of layers and reliable waterproofs.

Detours // Allow time to day hike in Argentina’s world class Los Glaciares National Park, explore Torres del Paine in Chile, or connect this route with the 621-mile (1000km) Carretera Austral.

© Cass Gilbert

riding with horses on the Patagonian pampa

- EPIC BIKE RIDES OF THE WORLD -

MORE LIKE THIS

REMOTE RIDES

SALAR DE UYUNI, BOLIVIA

Cycling atop the salt crust of Bolivia’s Salar de Uyuni – and the more petite but perfectly formed Salar de Coipasa – is an undisputed highlight of many a South America journey. It’s a high-altitude ride that takes five or six days, segmented by an opportunity to resupply with water and food at the midway settlement of Llica. As the largest salt flat in the world, cycling here provides an other-worldly experience. There’s nothing quite like pitching your tent on a bleached white canvas, seasoning your dinner with the salty ground on which you’re sitting, and awakening in the morning to a glow of ethereal, lavender light. This journey can only be undertaken in Bolivia’s winter, as during summer the salt lakes are inundated by seasonal rain.

Start // Uyuni

End // Sabaya

Distance // 186 miles (300km)

CANNING STOCK ROUTE, AUSTRALIA

Riding Western Australia’s Canning Stock Route is a monumental challenge. In fact, it’s only been successfully completed by a handful of riders. Given the extended sections of soft sand, dunes and corrugation that typify such a vast, remote and unforgiving desert, this is a route that can only be undertaken on a fat bike, sporting a colossal tyre size of at least 4in in width. You’ll also need to carry enough food for more than 30 days, and water for four- to five- day stretches at a time. Despite the 51 old wells that punctuate the route, only a handful can be relied upon. But for anyone prepared to tackle this physical and logistical feat, the reward is complete, unmatched desert solitude.

Start // Hall Creek

End // Wiluna

Distance // 1243 miles (2000km)

FRIENDSHIP HWY, TIBET–NEPAL

Bookended by the cities of Lhasa and Kathmandu, the Friendship Hwy crosses the Tibetan plateaux via a series of high elevation passes, the highest of which reaches 5251m. Given that much of the pedalling takes place at over 4000m – across the Roof of the World, as it’s often called – pre-ride acclimatisation is vital, particularly if flying into Lhasa. The journey itself takes 3 weeks, including a detour to Everest Base camp, promising stunning views of the planet’s highest peak. Elsewhere, the Himalayan showcase continues, with the likes of Cho Oyu (8241m) and Shishapangma (8042m) prodding into the atmosphere. Leaving the Land of Snows is like entering another world; Nepal’s green backdrop provides a sudden and stark change from Tibet’s vast and windswept plateau. Given the political sensitivity of the area, independent travel can be limited. Currently, the Friendship Hwy can only be ridden as part of an organised group.

Start // Lhasa, Tibet

End // Kathmandu, Nepal

Distance // 594 miles (956km)

© Nancy Brown | Getty Images

Lake Namtso on the Friendship Hwy, north of Lhasa

- EPIC BIKE RIDES OF THE WORLD -

THE NATCHEZ TRACE PARKWAY

The Natchez Trace coasts through three Southern states of America, with thousands of years of history beneath your wheels and the sounds of Elvis in your ears.

At the northern terminus of the Natchez Trace Parkway, a milepost sticks up like a thumb on the side of the road. For many bikers, the brown sign represents the final lap, an exclamation point punctuating a two-wheeled odyssey that started two states away in Mississippi. For southbound cyclers like me, however, the marker is just the beginning. ‘Mile one,’ I exclaim ceremoniously, translating the sign’s three digits.

Over 10 days, I will pedal 444 miles (714.5km) from Nashville to Natchez, with a small wedge of Alabama in between. During my journey on the National Park Service road, I will roll through thousands of years of history, and not necessarily in order. I will follow in the footsteps of giant sloths and Chickasaw tribes, Kaintucks (Ohio River farmers and boaters) and Elvis, and Civil War soldiers and Oprah.

During hours-long rides, I will share the two-lane paved road with a handful of cars and motorcycles (the maximum speed limit of 50 miles/80km per hour deters rushed drivers), kindred spirits in padded shorts and helmets (peak season is autumn) and countless critters, including armadillos both dead and alive. And in and out of my saddle, I will experience Southern traditions that touch all aspects of life, from grits to music to football.

The New Trace, a straight arrow that dates from 1936 and roughly parallels the original foot trail, is not as arduous as the Old Trace, a meandering dirt path studded with rocks and roots. Nor is it as perilous: the poisonous snakes, tribal attacks and bandits appear only in yellowed accounts.

© Jeff Crass | 500px

Nashville, capital city of country music

But the communities are still dispersed like distant beacons. I have to watch the clock and my pace if I want to arrive at my lodging before nightfall – or, in the case of Leiper’s Fork, to catch open mic night at Puckett’s Grocery & Restaurant.

The 19th-century village, about 15 miles (24km) from the Trace entrance in Tennessee, is a darling among Nashville stars (the Judds, Carrie Underwood) and troubadour musicians seeking an impromptu jam (Aerosmith bandmates). When I enter Puckett’s, two young guitarists are electrifying the crowd with a Jimi Hendrix cover. I’m introduced to the unofficial mayor of Leiper’s Fork, a towering grey-haired man in a baseball cap named Goose.

‘This is one of the prettiest parts of the country, especially on the Trace,’ Goose yells into my ear, mentioning the maple and oak trees lining the parkway. He then directs my gaze to the stage, pointing to the keyboardist, who plays with Neil Sedaka, and the guitarist, who tours with Ted Nugent. He widens his sweep to point out Naomi Judd’s husband and a CIA agent who I am supposed to forget as soon as I see her.

THE HOME OF ELVIS

The birthplace of Elvis is the B-side of Graceland. In Tupelo you can visit the 15-acre park complex that houses both his humble childhood home and a museum of memorabilia. There’s also the legendary Tupelo Hardware Company, which still sells tools and instruments. Inside the store, stand on a black X that marks the spot where the future rock n’ roll star picked out his first guitar.

I don’t have much time to ease into the Trace. The longest distance – 72 miles (119km) – falls on the second day. The Tennessee portion is the hilliest, slowing my speed and stretching my energy reserves. Informational placards and historic sites further impede my progress. At the Meriwether Lewis National Monument, I meet a New Orleans-bound skateboarder tending to his injuries after a crash and the Nashville couple who have been cheering me on with fist-pumps through their sunroof. We discuss the rumour that the famed explorer died of syphilis. But the National Park refuses to gossip. An interpretive sign by a stone memorial elusively explains that his life ‘came tragically and mysteriously to a close.’

“At FAME Recording Studios, an employee invites me inside Studio A, where Aretha Franklin cut two hits”

In Florence, at Milepost 338, a group of motorcyclists huddle around Tom Hendrix to hear the emotional tale of his great-great-grandmother. As a Yuchi girl, he explains, she was forced to leave her tribal land in Alabama for Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma. She was restless, however, and reversed course. She spent five years searching for her way back home.

In the 1980s, Tom started to collect millions of pounds of rocks and build the 1½-mile/2.5km-long Te-lah-nay’s Wall to honour her life and spirit. The eastern portion runs in a direct line and represents the Trail of Tears; the western section sprawls in many directions, symbolising her meandering return route.

At Muscle Shoals, about 20 miles (32km) off the Trace in Alabama, is where some of the biggest names up and down the radio dial have recorded, such as Otis Redding, Etta James, Paul Simon, Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones and Band of Horses. At Muscle Shoals Sound Studio, a museum guide encourages me to shake a pair of maracas in the booth where Mick Jagger and Keith Richards belted out three songs on ‘Sticky Fingers’. A German tourist ducks into a sacred but still-operating space: the bathroom where Richards wrote ‘Wild Horses’.

At FAME Recording Studios, an employee invites me inside Studio A, where Aretha Franklin cut two hits and Alicia Keys played the piano for the 2013 documentary film, Muscle Shoals. In Studio B, he tells me that Duane Allman once slept and performed here. For the next 60-odd miles (97km) to Tupelo, I have Southern rock stuck in my head.

For 361 miles (581km), I have biked solo. But one morning, I unexpectedly become a duo. A French-Canadian in striped long underwear sidles up next to me and strikes up a conversation that endures for more than 80 miles (129km). We become a trio when a former turkey farmer from North Carolina joins us.

We count down the final distance together, with the French-Canadian throwing up his arm at significant intervals. At the three-mile (5km) mark, I start to feel a mix of elation and deflation. At the last mile (1.6km) of Natchez, I pedal slower, savouring it as much as I did the first in Nashville. AS

TOOLKIT

Start // Nashville, Tennessee

End // Natchez, Mississippi

Distance // 444 miles (714.5km)

Getting there // From Natchez, the airports aren’t that close. Alexandria (Louisiana), is 70 miles (113km) away; Baton Rouge (Louisiana) is 90 miles (145km). Catch a Greyhound bus to the start of your ride or hire an airport shuttle. Nearby bike shops can box and ship your wheels.

Where to stay // For overnight options, cyclists can pitch a tent at more than a dozen campgrounds, including several bicycle-only sites, or pedal into Collinwood, Tennessee; Florence, Alabama; and Houston and Kosciusko in Mississippi.

Where to eat // The Trace does not provide any food concessions beyond the rare vending machine at a rest stop. Pack meals in panniers.

More info // www.natcheztracetravel.com

© Carol M. Highsmith | Getty Images

FAME recording studios in Muscle Shoals, Alabama

- EPIC BIKE RIDES OF THE WORLD -

MORE LIKE THIS

ALL-AMERICAN RIDES

RAGBRAI, IOWA

Short for the Register’s Annual Great Bicycle Ride Across Iowa, RAGBRAI connects the dots of small towns stretching from the western shores of the Missouri River to the eastern banks of the Mississippi River. The ride, held during the last full week of July, started in 1973 as a six-day excursion, and every year the organisers plot a new route, shuffling the eight host communities procured for overnight stops. Despite the changes, several constants persist: the course distance and the direction from west to east, to avoid strong headwinds and biking into the sun. The landscape highlights country life, with red barns, silos, and fields carpeted in corn, wheat and sunflowers. And, contrary to pancake jokes, your legs will learn that Iowa is not flat.

Start/End // Changes annually, with the itinerary released in late January (www.ragbai.com)

Distance // On average 468 miles (753km)

More info // www.ragbrai.com

BLUE RIDGE PARKWAY, VIRGINIA TO NORTH CAROLINA

The iconic Blue Ridge Parkway rises and falls like a roller-coaster track running from Virginia’s Shenandoah National Park to North Carolina’s Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Most bikers budget about 10 days to complete the 469-mile (755km) route, which crosses four national forests and features 176 bridges, more than two dozen tunnels and hundreds of historic sites. Riders will experience the America that inspires patriotic songs: uninterrupted forests, burbling rivers, splashy waterfalls, vibrant wildflowers or foliage (depending on the season), and mountains haloed in clouds. Roadside diversions abound, such as the Blue Ridge Music Center, Julian Price Memorial Park and Craggy Gardens. Time your visit to Waterrock Knob with the sun’s sky spectacle.

Start // Shenandoah National Park near Waynesboro, Virginia

End // Great Smoky Mountains National Park near Cherokee, North Carolina

Distance // 469 miles (755km)

GREAT ALLEGHENY PASSAGE (GAP), MARYLAND TO PENNSYLVANIA

The chirps of bike bells have replaced the toots of train whistles that once rang through the corridors of the Great Allegheny Passage (GAP). The 150-mile (241km) biking and hiking trail (no cars allowed) sprang from mostly abandoned railbeds laid between Cumberland, Maryland. and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The trail is flat and leisurely, and coasts by some remarkable landmarks. On the 13-mile (21km) Frostburg-to-Meyersdale leg, for example, the wow list includes the Mason–Dixon Line into Pennsylvania; the 3,300ft-long Big Savage Tunnel, which was named after the stranded 18th-century surveyor who had offered himself up as food to save his men; the Eastern Continental Divide, the trail’s highest point at 2390ft; and the curved Keystone Viaduct. Charming towns such as Confluence, on the Youghiogheny River, and Ohiopyle, a hyperactive hub of outdoor activities, entice bikers to hop off and stay awhile.

Start // Cumberland, Maryland

End // Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Distance // 150 miles (241km)

© Pat & Chuck Blackley | Alamy

autumn foliage on the Blue Ridge Parkway, viewed from Waterrock Knob

- EPIC BIKE RIDES OF THE WORLD -

A CIRCUIT OF SAN JUAN ISLAND

A breezy half-day spin around San Juan Island passes fragrant lavender farms, groves of misty pines, gorgeous coastline, and pods of orcas.

Nestled between Seattle and the Canadian border in the postcard-perfect Puget Sound, San Juan Island is one of several that comprise the archipelago of San Juan Islands. Each of the islands are filled with stunning sights and quaint diversions that make a lovely escape for casual cyclists. Each island also has a particular appeal for people who love to travel with their bicycle – the laidback cruising on Lopez Island versus the slightly more heart-racing terrain of Orcas Island – but the picturesque San Juan Island is just right, offering maximum views and a taste of adventure that is approachable for a wide range of riders.

I discovered the bicycle-friendly roads that circle San Juan Island offer something new around every bend – rocky outcroppings that plunge into sparkling waves, lofty groves of Douglas fir, migratory birdlife, bucolic farms and miles of coast. But this 35-mile (56km) ride has just as many excuses to get off the bike, including a pair of picturesque harbour towns, roadside farm stands, and historic sites that speak to the region’s colourful past. The biodiversity of such a small island is fascinating – from dense conifer forest and open farmlands to picturesque beaches. Modestly rolling terrain, 247 annual days of sunshine, and breathtaking scenery makes it an ideal destination to ride.

My partner and I began at the island’s main port, Friday Harbor, connected by frequent ferry service to Washington. After fuelling up on breakfast at one of the harbourside cafes we were on our way.

Heading south out of town on Argyle Rd, we followed the signs to the American Camp visitor center, one of the two former 19th-century military camps that make up the San Juan Island National Historical Park. A ranger was on hand answering questions about the so-called Pig War, an 1859 boundary skirmish between the British and the US. The conflict owes its colorful name to the incident that sparked it: a dispute between an American farmer and an employee of the Hudson’s Bay Company who owned an unruly pig. Fortunately, the pig was the only casualty.

© Danita Delimont | Alamy

looking out over the San Juan archipelago with Mt Baker in the distance

A few more miles south and we reached South Beach, which has incredible views across the Strait of Juan de Fuca to the snow-capped drama of the Olympic Mountain range. We continued south to the Cattle Point Lighthouse along a steep bluff and paused at pull-offs for mesmerising views of Vancouver Island, Olympic National Park and Port Angeles.

Continuing west and north we made our way to Lime Kiln Point State Park – known to the locals as Whale Watch Park – which is one of the island’s most popular spots for a picnic. If you’re here in the summer, you have a good chance of spotting a pod of orca whales. There are volunteer whale watchers at the most popular overlooks, scanning the waves for orcas and other species of whales that include gray, humpback, and minke. This is a good excuse to park the bike, as the area is great to explore on foot. We wandered around an historic lighthouse, an interpretive centre with hands-on exhibits and displays about the orcas, and an ancient lime kiln. This is where you should top-up your water as well, as the slightly more vigorous riding is about to begin.

“Volunteer whale watchers scan the waves for orcas and other species of whales that include gray, humpback and minke”

Leaving Lime Kiln Point, the road gains a couple of hundred feet of elevation, passing some of the most spectacular coastal sights on the entire ride. Over the hill, we cruised down to San Juan County Park. If you missed the whales at the first stop, try again; the unfortunately named Smallpox Bay is another good spot to look for the pods. This part of the island is home to all kinds of other wildlife as well, including deer and bald eagles. Turning left on West Valley Rd, we rolled past the curious gang at the Krystal Acres Alpaca Farm – which has a great gift shop of locally made goods – before seeing signs for English Camp. Situated on an open, grassy patch, this is another good place for a rest.

THE ORCAS OF SAN JUAN ISLANDS

The San Juan Islands host three resident pods of black and white orcas – a population of just over 80 whales, many of whom are known on a first-name basis by the locals. The orcas call these waters home between May to October. If you want to see them up close, consider a kayaking excursion – but your chances are just as good to spot them as they swim near the shore.

As we continued down the road toward Roche Harbor, we started thinking about lunch. Locals recommended the Westcott Bay Shellfish Company, a small family farm that produces deliciously briny oysters and has no-frills picnic tables where you can enjoy the sun, and shuck your lunch. But we were in the mood for something a bit heartier, so headed into town.

Centred around a tidy port and the stately Hotel de Haro, the marina at Roche Harbor is a charming lunch stop. Lime production was a major industry here during the late 19th century, but these days the small harbor is a magnet for yachting retirees from the Pacific Northwest. Explore the lanes of the historic village before making your way to the San Juan Islands Sculpture Park, a 19-acre park with more than 150 works by local and international artists, including some amazing kinetic sculptures.

Back in the saddle, it was a straight shot back to Friday Harbor – just under 10 flat miles (16km) on Roche Harbor Rd. Halfway back, we passed the lovely Lakedale Resort – a lakeside hotel with some options for glamping – before arriving at the final diversion, San Juan Vineyards. We did a bit of tasting (we earned it!) before bringing a glass out to the patio and taking in the warm evening light. A quick three miles (5km) more brought us back to the start in Friday Harbor, for hot showers and an elegant dinner. NC

TOOLKIT

Start/End // Friday Harbor

Distance // 35 miles (56km).

Getting there // Get to the island via the Washington State Ferry from Anacortes (www.takeaferry.com) or from Seattle’s seasonal Victoria Clipper. Seasonal ferries also depart from Bellingham or Port Townsend.

Bike hire // There are plenty of bike rental options in Friday Harbor, including high-end road bikes.

Where to eat/stay // Friday Harbor is San Juan Island’s largest town, and has a host of dining and sleeping options. Romantic B&Bs are scattered all over the island.

When to ride // The best time of year for a visit is between late April and early September.

More info // For complete information on visiting the island, including cycling resources, see www.visitsanjuans.com.

© mlharing | Getty Images

the San Juan Islands have three pods of resident orcas

- EPIC BIKE RIDES OF THE WORLD -

MORE LIKE THIS

ISLAND RIDES

VIEQUES ISLAND, PUERTO RICO

Six miles (9½km) off the southeastern coast of Puerto Rico, Vieques is a little strip of paradise – just 21 miles (38km) long and four miles (6½km) wide. Much of this enchanted place was owned by the United States Navy until 2003, when two-thirds of the island transitioned from a bombing range to lush nature reserve. Pedal down its long, dusty roads to find secluded beaches otherwise inaccessible by car. Many of the best of these have no names, but Red Beach is worth seeking out; the blonde crescent strip of sand lies beyond the cracked asphalt airstrip of the former Camp Garcia. Even during the high season (between late November and May) you’ll have the place mostly to yourself.

Tour // Black Beard Sports (www.blackbeardsports.com) has rentals and leads tours

NANTUCKET ISLAND RIDE, USA

Filled with New England ambience, history, and fresh-air vistas, Nantucket is a relaxing destination that’s perfect to explore by bike. The island is only 14 miles (22½km) long and three and a half miles (5½km) wide, so a dedicated cyclist can spin around its entirety in one day, but you’ll be better off to take some short rides around town and to the outlying beaches. Start with the boutiques and restaurants on the cobbled streets of historic Nantucket Harbor before navigating the network of smooth bike-paths past ocean views, migratory birds, and windswept beaches. Refuel on bowls of chowder among the rows of neat gray-shingled cottages in the old fishing village of Saiconset.

Bike hire // The Island Bike Company (www.islandbike.com) has a range of bikes, including cruisers and roadies

DINGLE PENINSULA, IRELAND

Between the craggy range of mountains and rocky cliffs that plunge into the Atlantic, the Dingle Peninsula is a joy for cyclists, who can ride a demanding day-long loop that passes historic ruins, roaring coastline, and amazing beaches. The peninsula is something of an open-air museum, dotted with more than 2000 Neolithic-Age monuments built between 4000BC. and early Christian times. The village of Dunquin has many crumbling rock homes that were abandoned during the famine. You’ll also pass the Gallarus Oratory, one of Ireland’s most well preserved ancient Christian churches. As you near the end of the loop, pull off for a quick stop at the 12th-century Irish Romanesque church with an ancient cemetery before returning to Dingle Town, where you’ll find plenty of pubs (many of which are hardware stores by day) to toast the adventure.

Start/End // Dingle Town

Distance // 25 miles (40km)

© Jan Miko | Shutterstock

there are few straight roads on the Dingle Peninsula, Ireland

- EPIC BIKE RIDES OF THE WORLD -

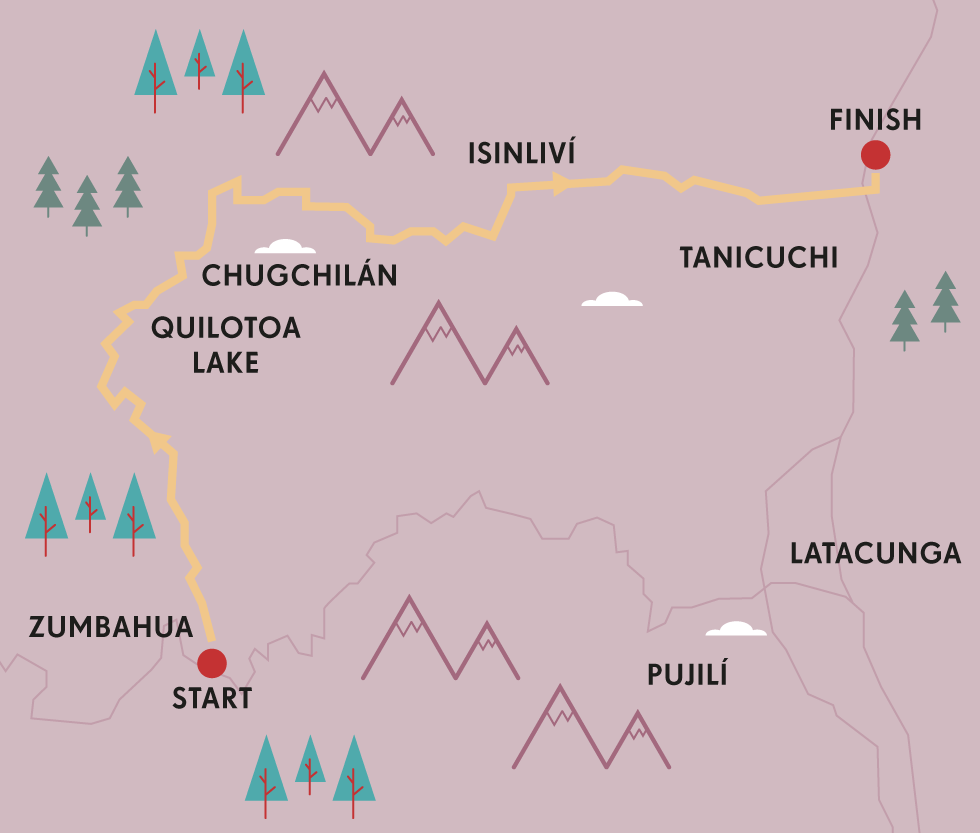

FAMILY BIKEPACKING IN ECUADOR

Picturesque Quilotoa Loop feels suitably off-the-beaten-track, but with a range of comfortable digs along the way, cyclists can recharge before tackling Ecuador’s tremendous inclines.

For those unfamiliar with the topography of South America, let me assure you of this: the Ecuadorian Andes are a deeply crumpled land. A slim band squeezed between the expanse of the Pacific Coast and the vast sprawl of the Amazon, it abounds with microclimates, determined more by geography and altitude than by any season. Within these folds, one steep-sided valley dovetails into the next. Cradled between two volcanic ranges, they form the Avenue of the Volcanoes, as coined by Alexander von Humboldt, the Prussian naturalist who journeyed through the continent in the 19th century.

Big mountains, big views... and, above all, big climbs: adventurous cycling, without doubt. But family friendly? Yes and, somewhat surprisingly, very much so.

We shared our Ecuadorian adventures with three brothers I’d first met while cycling through the country three years prior. Mountain guides by trade, they lived offgrid on an organic family farm outside Quito. In the interim, we’d kept in touch – and we’d all had children. When the chance came to visit Ecuador once again, this time I travelled with my partner and our two-year-old son Sage, so we might experience this beautiful and unfeasibly rugged country together.

In any shape or form, this ride would have been epic enough. Apart from the quiet dirt tracks, small mountain settlements, and fluffy roadside llamas, its backdrop was nothing short of spectacular: high altitude Ecuadorian paramo, the alpine tundra for which the country is known, and the emerald-tinted, 2mile (3.2km) wide Quilotoa crater lake, a definitive highlight along the Avenue of the Volcanoes.

© Cass Gilbert

pedalling into the wilds of Ecuador

But factor in no less than eight bicycles and five accompanying trailers, charged with a payload of children ranging in age from six months to three years, and such a journey takes on an even more memorable character. Despite the afternoon downpours and the occasional synchronised meltdowns, our pint-sized expedition proved to be an incredible life experience for everyone.

Together, we blazed a trail of family mayhem through the countryside. We rubbed shoulders with poncho-clad horse riders, picnicked amongst fields of quinoa, visited an indigenous market, and lingered in village playgrounds.

We kept distances short, and tried to harmonise riding times with napping schedules. When our three toddlers needed a break, we stopped and played football, helped them climb trees, or just explored the land. And what a land it was. A fertile patchwork of vertiginous fields clung to steep-sided slopes, surrounded by both soaring peaks and crumbling canyon cliffs. Pigs scuffled around by the road, men sauntered by with machetes on their hips, and women crammed their colourful shawls with fresh corn, their felt hats peeking out through the foliage.

MARKETS

Ecuador’s markets are not to be missed: vibrant colours, towering displays of food and a real sense of community. Fresh fruit juices and delicious snacks abound – grilled plantain is safe to eat, and a sure-fire toddler favourite. Usurping the main square each Saturday, there’s Zumbahua’s market – at the beginning of the Quilotoa Loop. Or, as a separate trip, don’t miss Otavalo, the best place to stock up on beautifully knitted jumpers and ponchos for children.

“Reaching the summit was rewarded with a feast of local produce, cheese and ripe avocados that had filled our panniers”

The route itself looped south-east through Ecuador’s Central Sierras. After stopping to applaud the natural watery wonder of Quilotoa, and scout briefly along the knife edge of its crater, it took us through the small settlement of Chugchilán, where we detoured into the dewy delights of the Illiniza Cloud Forest. There, fingers of mist curled through the trees, enveloping the land, filling every nook and cranny with silence. When the sun occasionally permeated through, it was subtle and shadowless, painting the mountains in gigantic, camouflaged swatches.

Up and down we rode, rarely a flat moment for respite. Climbs had our derailleurs clattering frantically through the gears, spinning our legs in the lowest cadences we could find, the ballast of our toddler cargo weighing us down. In immediate riposte, descents demanded we pull on brake levers like reins on a horse, lest our trailers shunt us forwards. Added to this, the terrain was often bumpy, sometimes even cobbled. Yet when I looked back to check on Sage, more often than not he was sound asleep, oblivious to our efforts.

Travelling over the winter holidays, we celebrated Christmas in Isinliví, a picturesque settlement perched in one of the region’s verdant valleys. As we came to appreciate, South Americans know how to party, whatever time of the year. The main square awash with revellers, countryside cowboys and a roving brass band that relentlessly circled its stony streets. To Sage’s delight, it even boasted an antiquated funfair, featuring a merry-go-round that spun with dizzying speed.

Isinliví was also our last staging post before we tackled the longest climb of the trip, a Herculean undertaking that involved 1000m in altitude gain, on an unpaved road at that. Inevitably, this final undertaking had us all off the bikes and pushing, our Lilliputian team of toddlers enthusiastically lending a helping hand too. When the summit finally came, it was rewarded with a feast of local produce, cheese and deliciously ripe avocados that had filled our panniers. Then, with a last gaze out towards the highland paramo, we dived into the whirligig descent that lay ahead, the flags of our trailers snapping in the wind.

Despite the diminutive daily distances, I won’t lay claim that family bikepacking is easy; without doubt, it poses its own set of mental and logistical challenges, quite apart from any physical toils. But I couldn’t more highly recommend trying one out, wherever it may be in the world, for however many days you may have. Gather the troops and brew up a plan. Choose a route that everyone will enjoy. Take the time to luxuriate in being off the bike as much as you are on it. I can guarantee that such undiluted family time will warm the heart and feed the soul. For everyone involved. CG

TOOLKIT

Start // Zumbahua

End // Lasso, on the Pan-American Hwy.

Distance // 68 miles (110km)

Getting there // Both Zumbahua and Lasso can be easily accessed by bus from Quito.

Where to stay // Hostal Llullu Llama in Isinliví. For ecominded luxury, the Black Sheep Inn, near Chugchilán.

What to take // Pack light and make use of traveller-friendly accommodation en route.

Climate // Put aside several days in Quito to acclimatise before heading into Ecuador’s high country.

Hot tip // Ecuador’s inclines can be long and unreasonably steep (but ultimately rewarding!).Trucks regularly ply Ecuador’s mountain roads. For a few dollars, flag down a driver, and enjoy a lift to the top of the next mountain pass.

© Cass Gilbert

keep spirits and sugar levels up with regular stops at street markets

- EPIC BIKE RIDES OF THE WORLD -

MORE LIKE THIS

FAMILY BIKEPACKING RIDES

SALIDA, COLORADO, USA

The Great Divide Mountain Bike Route (GDMBR) is famed for its Herculean race, in which self-supported riders tear across the Rockies. But broken up in bite-size portions, it also has all the ingredients for a series of wonderful family bikepacking adventures. Indeed, it doesn’t get much better than the high grasslands and aspen groves above Salida, Colorado, especially during the technicoloured splendour of autumn. There, a dirt road loop can be formed using Aspen Ridge and the backbone of the GDMBR. Salida’s polished, historic redbrick downtown – distantly echoing an insalubrious past as a Wild West railroad settlement – also features a park in which to picnic, a playground, a climbing wall and a river to soak in. Kid trailers are almost as common as the dual suspension mountain bikes that roam the streets.

Start/End // Salida, Colorado

Distance // 52 miles (84km)

More info // www.bikepacking.com/routes/family-bikepacking-salida

WHITE RIM, UTAH, USA

Even within the vast expanse of the American South West, Utah holds its own particular appeal. There’s an inordinate number of national parks and natural wonders vying for attention: a medley of canyons, cliffs, buttes, arches and tabletops, hewn over millennia from its quintessential red rock. The White Rim Trail, in the south-eastern portion of the state, is a rare bicycle touring gem, simply because it’s difficult to imagine how a ride could be more perfectly formed. Located in the heart of Utah’s Canyonlands National Park – eroded into shape by the mighty Colorado and Green Rivers, this 97-mile (156km) loop boasts a succession of one superlative panorama after the next. Combine this with a wellpacked dirt road, sublime camping potential and complete, utter desert silence, and it’s everything you seek in a weekendsized adventure.

Start/End // near Moab, Utah

Distance // 97 miles (156 km)

More info // www.nps.gov/cany/planyourvisit/whiterimroad.htm

CONGUILLÍO NATIONAL PARK, CHILE

The Conguillío National Park lies at the northern tip of the Chilean Lake District, and envelopes the 3125m Llaima Volcano. It’s a lunar landscape where islands of fertile earth lie stranded between lava flows frozen in time – or at least until the next eruption. Quiet mountain roads make for great, if challenging, family bikepacking, combining an exploration of the park with a ride to Lonquimay, through the neighbouring Reserva China Muerta. Dotted through the area, standing nobly in tranquil groves, are the enchanting Araucaria araucana or ‘Monkey Puzzle’ trees, so named as it was thought that climbing them would flummox even a monkey. These bizarre, bandy, Seussianlike creations reach up to 40 m high, their tentaclelike branches surely protecting them from any primate intrusion while also fascinating children.

Start // Melipueco

End // Lonquimay

Distance // 50 miles (80km)

© James Schwabel | Alamy

riding through downtown Salida, Colorado

- EPIC BIKE RIDES OF THE WORLD -

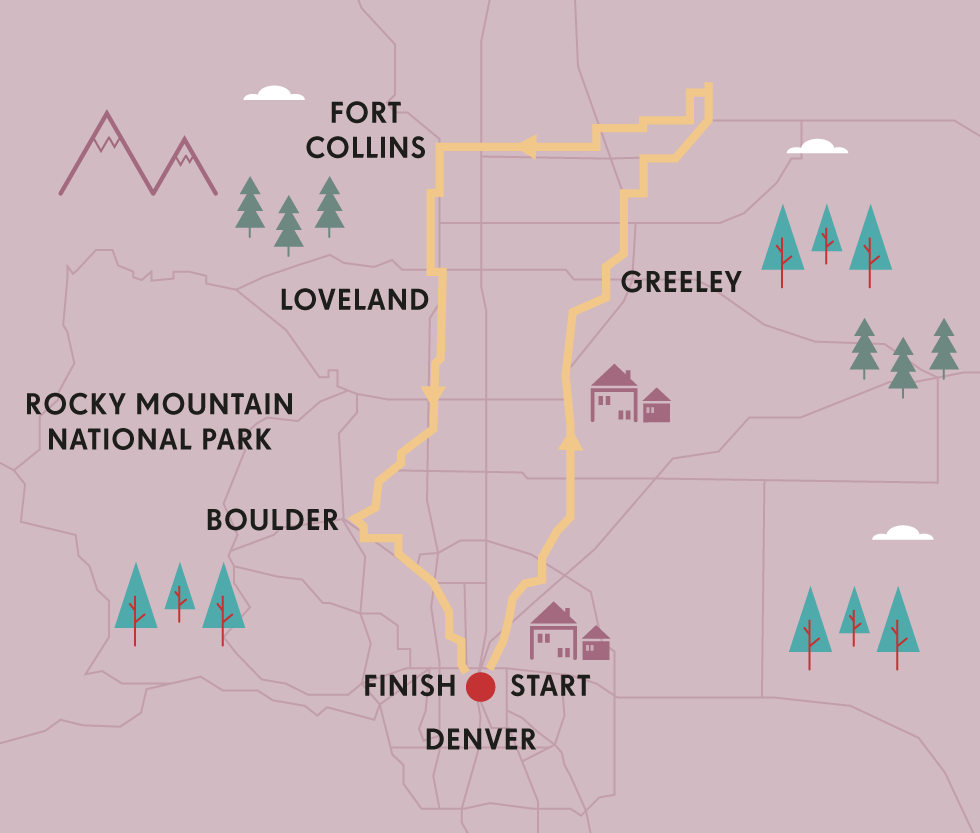

COLORADO BEER BIKE TOUR

Year-round sunshine, world-class cycling, and hundreds of breweries – quench your thirst after a long day on the bike with some of America’s best craft beer.

Iget off the bike, legs full of lead and heart thundering, face tingling from the wind and mouth full of cotton. If this was a typical ride, I’d grab my water bottle and find the nearest cheeseburger. But taking in the scenic regions of Colorado’s north by bike is anything but typical. On this ride, I’ll savor the marriage of the region’s two perfectly complementary pastimes at every stop: mind-blowing cycling and mouthwatering beer. A blissful 20-mile (32km) descent from the mountains and an icy pint of citrusy, grassy, dry-hopped double IPA? This is my kind of recovery regimen.

Colorado has long been a hotspot for road cycling and mountain biking, and boasts more microbreweries per capita than anywhere else in the US. For a beer-loving cyclist, it’s a no-brainer.

I start in the state’s capital, Denver, which has transformed from a frontier cow town into an urban capital of the American west. The city itself might be destination enough for casual cyclists – an excellent bike network includes long, leisurely routes along the Platte River Parkway, the Cherry Creek Bike Path, and trails to neighbouring suburbs. You can even use the excellent B Cycle program, which has bikes stationed throughout the city. But one look at the peaks of the ‘14ers’ (local speak for a 14,000ft mountain [4267m]) looming on the horizon, and I knew that a serious two-wheel adventure was ahead.

Denver is the perfect embarkation point for my beer-themed trip. I was a month early for the endless tasting at September’s Great American Beer Festival – but consoled myself with a fun, boozy overview of the city’s breweries from the Denver Microbrew Tour. A few of my favourites include the Great Divide Brewing Company, where the spectrum of seasonal beers are all beautifully balanced (be careful, many of them are over 7%), an outpost of the excellent Breckenridge Brewery, and the weekly rotation of taps at the Denver Beer Co.

© Bill Ross | CORBIS

Denver at dawn

Fully hydrated and rested up, I hit the road. My next major stop would be Fort Collins, a college town that perfectly merges Colorado’s beer and bike cultures. Although a serious cyclist could do the trip in a long day, I took the 100-mile (161km) route into two days with an overnight in Greeley. With the pancake-flat roads and a tailwind, I blasted out of Greeley for a cruise through the unending green expanse of the Pawnee National Grassland, a magical sea of swaying hip-high grasses that were once prime buffalo hunting land. There’s something hypnotic about the rhythmic sway of the prairie.

“Riding west brought me to Fort Collins, the essence of the trip, its bike-packed streets dotted with great breweries”

Navigating a few extra miles brought me to the Pawnee Buttes, two 300ft formations that leap dramatically out of the flatlands. Aside from free-roaming cattle, these back roads are mostly free from traffic, and toward the end of the day I caught the flash of a white-tailed antelope bounding through the fields.

Riding west brought me to Fort Collins, which straddles Colorado’s topographical divide, at the point where the Rockies begin their rise. This town is the essence of the trip: the bicycle-packed streets of Fort Collins are dotted with great breweries. And the city is mad about cycling: the Fort Collins Bike Library offers free bikes to anyone who passes through.

THE COLORADO TRAIL

With some 535 miles (861km) of twisting singletrack, jaw-dropping views, and rollercoaster elevation, the Colorado Trail is one of the world’s great long-distance mountain bike journeys. Riding the entire trail – from Denver to Durango – takes about 20 days, and requires re-supply in mountain towns along the way. For the more casual rider, there are numerous day-rides that will give you a taste of this epic adventure. For complete information: www.coloradotrail.org.

This first stop in Fort Collins is the New Belgium Brewery. This employee-owned operation has brought its passion for bicycles, beer and sustainability to an international audience in recent years. The guides give me a playful walk through the facility that ends in a carnival-like tasting room before I head back to town for a stop at the Odell Brewing Company, a remarkable small brewery with the best IPA of the trip. If the sun was up, I would have hit the beer garden at Equinox Brewing, but the jagged horizon suggests that a good night’s rest is in order.

Anyone could close this loop by riding straight south on the relatively flat roads that skirt the edge of the Rockies. I’ve got a pint of stout or two to work off, so I’m up for the challenge of climbing Rist Canyon to Stove Prairie Rd. This route (loved by locals and a recent stage for the USA Pro Challenge) is tough, but the scenery is incredible. Ahead, mountains roll into view in shades of purple and blue. Behind, plains reach out in a checkerboard of green. All day, I’m surrounded by pines, massive boulders and rushing creeks. Heading south on Stove Prairie Rd, I lose all that elevation through the sweeping curves that lead to Loveland. Of course, there are plenty of places to fuel up in this small town as well, starting with the family-owned Loveland Aleworks, where the creative selection of taps is frequently rotating. This stop includes a pucker-inducing explosion of summer flavour with the Strawberry Sour.

The next day, I take the 35 miles (56km) between Loveland and Boulder in a few hours, allowing plenty of time for exploring the Boulder Creek Bike Path to end the penultimate day. Snuggled up against the Flatirons, this bohemian college town is in love with the outdoors. After chatting with the local characters on the Pearl St promenade, I grab a beer at Avery Brewing, and take a self-guided tour from the catwalk. The evening ends with some noodling guitar warriors at the Draft House, which brings in local bands every weekend. Another half-day in the saddle brought me back to Denver for a well-earned rest for my legs and my liver. NC

TOOLKIT

Start/End // Denver

Distance // about 350 miles (563km) in five or six days.

Getting there // Denver International Airport is an easy connection to many cities in the US and has several daily routes to Europe, Japan, Canada and Latin America.

Bike hire // A number of Denver shops will rent bicycles suitable for multi-day trips, including The Bicycle Doctor (www.bicycledr.com), and Bicycle Village (www.bicyclevillage.com). The big REI (www.rei.com) in Denver also rents bikes and camping equipment, and can arrange bike shipping.

Where to drink // The Beer Drinker’s Guide to Colorado has reviews and maps to Colorado breweries. Denver Microbrew Tour offers a great brewery overview.

More info // See www.bikedenver.org and www.denvergov.org, which has downloadable bike maps.

© Shutter18 | Getty Images

autumn colours at Boulder Creek

- EPIC BIKE RIDES OF THE WORLD -

MORE LIKE THIS

REFRESHED RIDES

CALISTOGA WINE TOUR, USA

A weekend amble through California’s wine country is an extremely popular way to get a taste of the region north of San Francisco. Although Napa’s roads can get clogged with tourists, a good alternative is to ride the relatively quieter roads surrounding Calistoga. Pedal north out of town on Hwy 29 and take Old Toll Rd up a side valley. A steep, shaded climb will pass a couple of family wineries before rejoining Hwy 29 and reaching the summit at the Robert Louis Stevenson State Park – an excellent place to rest, picnic, and take in the views. Coast downhill to Middletown and east through the lovely valley that’s home to the Guenoc and Langtry Vineyards. Then climb Butts Canyon and descend into the flowering meadows of Pope Valley. From here, connect to the celebrated (car-free) Silverado Trail, through the adorable downtown of St Helena, and head back to the start.

Start/End // Calistoga

Distance // 62 miles (100km)

VALLEY BEER TOUR, USA

The region of Western Massachusetts and southern Vermont gets called the Napa Valley of Beer for good reason – the clutch of creative craft breweries and excellent brew pubs makes it a beer-lover’s dream. Start this trip in Springfield, a half-day train ride from New York City. Here, you can enjoy old world beer-making traditions at The Student Prince, one of the best German restaurants in Western Mass. After a stein and a schnitzel, make your way along back roads to North Hampton, a college town with a number of great brew pubs, including the 40 taps of local and far-flung beers at Dirty Truth and the rowdy outdoor beer garden at the Northampton Brewery. This ride ends just across the Vermont state line at the The Whetstone Station Restaurant and Brewery, where riders can enjoy a view of the Connecticut River and refined small plates.

Start // Springfield, Massachusetts

End // Whetstone Station Restaurant & Brewery, Vermont

Distance // 66 miles (106km)

KENTUCKY BOURBON TOUR, USA

A ride filled with rich history, heady spirits, and Southern American charm, this trip takes in six of the best distilleries along the scenic, rolling rural roads of Central Kentucky. The terrain is moderately challenging (particularly with a couple of samples under your belt), so this is recommended for more experienced cyclists. Start in Lexington at the Jim Beam distillery, where you can get a detailed map of the region and turn-by-turn instructions. Along the route, you’ll sample America’s oldest spirit at the Heaven Hill Distillery, Maker’s Mark, Four Roses, Wild Turkey, and Woodford Reserve. In addition to the delicious bourbons, you’ll find rolling hills of bluegrass and picture-perfect horse farms.

Start/End // Lexington

Distance // 30 miles (48km)

More info // www.kybourbontrail.com

© Lottie Davies

showing you the way to the next whisky stop in Kentucky

- EPIC BIKE RIDES OF THE WORLD -

NORTH AMERICA’S PACIFIC COAST

With the shimmering Pacific horizon to your right and an endless ribbon of blacktop ahead, this ride traces the dramatic western edge of North America.

For cyclists who live to ride, this is a once-in-a-lifetime trip, the kind of experience that’s a culmination of years of daydreaming and months of planning. I’d wanted to ride an extended stretch of the Pacific Coast Hwy for years, but the challenge is no joke: the jagged western edge of the continent has plenty of long, tough climbs and lonely stretches of blacktop that demand tenacity and self-sufficiency. But the rewards make it one of my favourite rides. Sunsets enflame the horizon, dizzying cliffs drop into the crashing surf, and redwood giants tower above. Over the years, I’ve ridden plenty of beautiful miles on Hwy 1, but none more exciting than the stretch between Seattle and San Francisco – an epic 980 miles (1577km) with incredible sights, great camping and plenty of diversions.

Scores of cyclists make the southbound trip on the Pacific Coast Hwy every year – mostly in the summer. I took the trip solo, but the camaraderie of the riders who gather around nightly fires at the hiker-biker campsites balanced a month of solitary days in the saddle. I met John and Margaret, a pair of sweetly sardonic teachers sporting classic ’80s touring rigs, gadget-obsessed twin sisters from Victoria BC on their way to Los Angeles, and a handful of grizzled vagabonds attempting solo trips to Mexico and beyond. And everyone had a story – about troubleshooting a mechanical nightmare in the rain, or a truck-driving redneck with an axe to grind, or climbs that seemed never-ending.

Although I was determined to camp – there are established campgrounds every 50 to 60 miles (80 to 96km) along the route with sites designated for cyclists – there are also plenty of opportunities for so-called ‘credit-card’ touring, for riders who travel light and prefer a soft bed.

The complete trip between Seattle and San Francisco can be done in 15 days (for a powerhouse cyclist with very little gear), but I took twice as long with a fully-loaded touring bike. Although I met plenty of riders ticking away miles on a tight schedule, I knew quickly that this wasn’t my style. The flexibility of my itinerary enabled some of the trip’s rewarding memories: pints of world-class beer at the Six Rivers Brewery, naps under swaying redwood trees, and clifftop whale-watching. In other words, little pieces of heaven.

© Richard Price | Getty Images

Cape Sebastian State Park in Oregon

Before leaving Seattle, I spent an extra day or two fuelling up on the city’s excellent food scene. Exploring the narrow alleys and bustling stalls of Pike Place Market, I got some fancy campfire supplies for the days ahead, and dug into the city’s best: steaming bowls of ramen and fresh-that-day crab.

I began my detours as soon as the trip began, tacking on several days to ride around the Olympic Peninsula. With misty rides on near-empty roads, the trip began with a surreal tranquility. It didn’t take long to get what I came for: brackish ocean breeze and mind-blowing vistas, as I cruised along spine-tingling cliffs, shovelling down snacks at quirky little roadside bodegas.

It took a long three days to get around the whole thing, but it was worth every minute: views of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, quiet farms, remote beaches and ancient forests. The camping was a superlative highlight.

CONTINUING ON...

Although the ride from Seattle to San Francisco is a favourite section of the Pacific Coast because of the quality of the scenery, the relatively quiet roads and the superlative options for camping, a cyclist with enough time and energy can keep pedalling for weeks along the Pacific. The stretch from San Francisco to Los Angeles is also a scenic stunner, though narrow shoulders and heavier traffic make it more of a challenge.

More of the best Pacific Coast lies in the coastal campgrounds of Oregon, which make up the bulk of the trip. I loved Fort Stevens State Park, a 4200-acre park that has incredible biodiversity – everything from gusty dunes to freshwater wetlands – and a number of historic military sites from the WWII fortification of the coast. Many of the coastal Oregon parks further south made me consider lingering a bit longer than planned, like Cape Lookout State Park, where the beachside hiker-biker sites are blissfully remote from the RV sites.

Although the camping in Oregon is the best on the trip, I discovered the most jaw-dropping vistas south of the California border. The ride here is a constant parade of awe-inspiring natural beauty, particularly when you get to the smoothly paved Avenue of the Giants, a byway surrounded on all sides by towering old-growth redwood trees. (If you’re into mid-century kitsch, there are even several that you can ride through, near Leggett.)

Riding along the edge of the so-called Lost Coast, I paused for a breather and saw the white flumes of whales, in their migration to Mexico. As I pedalled further south, I slowed for the seaside holiday towns lining the coast of Northern California. In one of them, historic Mendocino, there’s a tidy grid of cute shops and four-star restaurants next to gorgeous headlands. I also paused for fresh seafood in Point Arena – which has an amazing bakery and an historic theatre.

By the time San Francisco got near, I was in great shape for the most challenging section of the ride, Sonoma County. Thankfully, this also has the best views, with rock formations in the waters that rival the dramatic power of the famed Big Sur coastline south of San Francisco. Here, Hwy 1 offers paved rollers along the cliffs – three days in the rhythm of 20 minutes of lung-burning climbing followed by 5 minutes of glorious descending.

Reaching the coastal farms that supply San Francisco’s famed foodie culture, I knew the end was near, and stopped into Point Reyes Station for fresh oysters and locally made triple cream cheese at the Cowgirl Creamery. By the time I crossed the Golden Gate – 28 days and 980 miles (1577km) after my departure – this epic trip proved that the most magical part about going somewhere was the process of getting there. NC

“The ride is a constant parade of awe-inspiring natural beauty, particularly when you get to the Avenue of the Giants”

TOOLKIT

Start // Seattle

End // San Francisco

Distance // 980 miles (1577km)

Duration // Just over two weeks, though it’s much more enjoyable with three weeks or more.

Getting there // If you fly in and out of Seattle, you can return with your bike via Amtrak at a modest additional fee, or ship your bike for a flat fee through REI (www.rei.com).

Where to stay // Hiker-biker campsites at the Oregon State Park System are only US$5 and they never turn away cyclists – even if the park is sold out.

What to read // Bicycling the Pacific Coast by Vicky Spring & Tom Kirkendall

When to ride // You can do this trip any time of year, but summer and autumn are best.

© earleliason | Getty Images

fog rolls in off the Pacific along the North California coast

- EPIC BIKE RIDES OF THE WORLD -

MORE LIKE THIS

WATERSIDE RIDES

CRATER LAKE RIM RIDE, USA

Riders in the Pacific Northwest get a certain far-off look in their eye when they talk about the otherworldly ride along the edge of Crater Lake, one of the most rewarding day-long rides in the Western United States. The gorgeous, deep blue waters of this volcanic lake in southern Oregon have a visual power that leaves a big impression – it reflects the surrounding peaks and sky like a mirror, inspiring panoramas that will take any cyclist’s breath away. (Or maybe that’s the 3000ft of elevation change at high altitude.) A strong cyclist could do the 35-mile (56km) loop around the lake in three or four hours. But, regardless of your skills, the spectacular road is almost never flat – you’ll be climbing or descending most of the day.

Start/End // Crater Lake Visitor Center

Distance // 35 miles (56km)

GERMANY’S BALTIC COAST

With the sea as your constant companion, a multi-day tour of Germany’s Baltic Coast offers gorgeous beaches, rugged cliffs, regional seafood and the bustle of historic coastal villages. Begin this summer tour of the coast in Flensburg and head east, towards Fehmarn Island, an excellent place to observe migratory birds. Along the way, you’ll see many of the seaside resorts lining the Bay of Lübeck that have been resplendently restored. A stop several days later in Lübeck will allow you to refuel with the city’s famed marzipan treats before you pedal on to the quaint Unesco-listed towns of Wismar and Stralsund – two Hanseatic League trading centres of the 14th and 15th centuries. The second island on this trip, Rugia, presents more excellent cycling, with dramatic cliffs, white beaches, and the wild beauty of Jasmund National Park.

Start // Flensburg

End // Jasmund National Park, Sassnitz,

Distance // 279.5 miles (450km)

THE FRENCH ATLANTIC

A trip along France’s longest cycling trail, appropriately named La Vélodyssée, can be enjoyed as a day-long cruise or a multi-day epic; the full trail is about 745½ miles (1200km) stretching from Brittany in the north to the Spanish border. With the Atlantic in view for most of the ride, this journey is best be done at an easy pace that allows you to savour the region’s pleasures – including cute seaside B&Bs, historic sea ports, and beautiful beaches. Although each of the route’s 14 sections has distinctive charms, seafood lovers should make it a point to include the path from La Barre-de-Monts to Les Sables-d’Olonne, which will allow you to tuck into fresh oysters. The section between Arcachon and Léon is also stunning, as the path passes deep forests and inland lakes.

Start // Brittany

End // Bayonne

Distance // 745½ miles (1200km)

© Hemis | Alamy

riding the Côtes-d’Armor in Brittany, France

- EPIC BIKE RIDES OF THE WORLD -

MOUNTAIN BIKING IN MOAB

Few places get mountain bikers as excited as Utah’s Moab – a desert dreamscape of slickrock and singletrack revered for its riding culture and infamous 24-hour race.

When my riding partner dismounts and picks up his bike, I figure there’s no shame in doing the same. I had a feeling that any attempt to ride this particular section of trail would end with me biting some dust, sprawled on my back with all the grace of an upended blister beetle – again – but I might have given it a stab.

That’s if I weren’t exploring Behind the Rocks with Mountain Bike Hall of Fame grandee John Stamstad, and if he considers something to be unrideable, then the argument is effectively over. Stamstad is the emperor of endurance cycling – a reputation he earned, in part, right here – on the route of the legendary 24 Hours of Moab cycle race that annually ran through the Utah desertscape from 1994 to 2012.

Having effectively invented solo 24-hour mountain-bike racing and pioneered the pursuit of Great Divide racing across America, Stamstad once set a world record by cycling a mountain bike across off-road terrain for 354.5 miles (570km) in 24 hours.

Suffice to say, when he gets off his bike, it’s for good reason. This spot is named Nose Dive, and bits of broken bicycles lie scattered in the dust all around – the bleached bones of the foolish few who have attempted to ride the dive. ‘I used to be able to pick a line through here,’ Stamstad laments. ‘But the jeeps have destroyed it now. You can’t ride out of it anymore, so there’s no point killing yourself on the descent.’

© Jordan Siemens | Getty Images

looking out over the mesas around Moab

Stamstad never actually won the 24 Hours of Moab – not least because the last time he did it, he insisted on riding a single-speed bike (and still came second) – but he’s done so many laps of the legendary circuit that he could ride it with his eyes shut (and very possibly has). The race route is a shortened version of the Behind the Rocks Lunatic Loop, a 28-mile (45km) trail that is probably Moab’s least popular. A ‘sandy sufferfest’ is how the guy in Poison Spider Bicycles described it when he heard where we were heading.

But I’m desperate to experience the epic course, and now the event is in hiatus, this is the only way. My legs are eternally grateful that we only have to ride the route once, and the rest of me soon discovers that July is not a month when even Stamstad would want to be riding multiple loops for 24 hours on the trot. We’re out early in the morning – long before the day comes to the boil, when temperatures in the rare shade simmer at around 100°F (38°C) – but perspiration quickly drenches my face and fills my eyes.

Stamstad shows me around every nook and cranny of the course, recounting tales from the trails as we roll. At one point I go sailing over the bars during a technical descent, and he thoughtfully attempts to spare my blushes by describing how he once passed the erstwhile race leader at this very place, as the guy lay on the ground with concussion. I’m obviously travelling somewhat slower, and it’s only my pride that gets concussed.

24-HOUR RACING

Another Mountain Bike Hall of Famer, Laird Knight, created 24-hour MTB racing – where riders attempt as many loops of a technical off-road course in 24 hours as possible – as a team pursuit. In 1996 Stamstad entered a 24-hour race in Canaan as a team, but all four names on the sheet were a variation of his own. He did the event solo, beat most of the field and invented a new form of endurance racing.

I get back into the saddle and we continue, rounding a stunning golden edifice of almost Uluru proportions, which my companion grinningly informs me is known as Prostitute’s Butte, because of how it looks from the air. The trail then runs across a seductive section of Moab’s iconic slickrock – smooth Navajo sandstone that appears sketchy, but actually grants knobbly tyres an uncanny amount of traction, allowing riders to roll over the most unlikely gradients while remaining rubber side down.

The 15-mile (24km) race circuit finishes shortly afterwards and we seek shelter from the inferno of the midday sun. At a diner in town, the menu includes an ‘All-day Mountain Bikers’ Breakfast’, which delivers a carb-laden load that would keep most riders fuelled for the duration of a 24-hour race.

Once the worst of the heat has passed, we explore the more popular routes that slither across the slickrock and skim the rim of the canyon, making Moab a hallowed haunt for mountain bikers, irrespective of the race. Incredibly, these classic tracks were laid down during the Jurassic period, and no human intervention has been required to make or maintain them as perfect MTB trails.

That said, the mega-popular, world-renowned 10-mile (16km) Slickrock Trail itself follows a series of white dots painted onto the rocks, which do jolt you out of the amber-tinted ambience of the natural surrounds somewhat, so Stamstad takes me on the wilder Amasa Back Trailhead route instead.

This adventure, another 10-miler, sees us ascend over 1000ft, climbing across sandstone all the way to a magical mesa top, with an astonishing vista across the Colorado River and Kane Creek. Beyond the rust-coloured desert, the La Sal Mountains on the horizon still have a dusting of snow, which seems almost impossible from the furnace of the canyon.

Numerous drop-offs, technical climbs and steep descents keep us on our game throughout this return route, and rolling around close to the canyon rim – which plunges away with hair-raising severity – demands serious concentration, but it’s not just the elevation that gives me goosebumps here.

Riding back to the trailhead, as thunder rumbles in the distance and forked-tongued lightning licks the distant range, it feels like I’ve ascended some sort of higher plane of mountain biking. And then I’m bounced out of my whimsical reverie by a red rock that has waited 200 million years just to throw me over the bars of my bike and bring me back to earth. PK

TOOLKIT

Start/End // Behind the Rocks/24-Hours of Moab route: US-191, just beyond Kane Springs Picnic Area; Amasa Back Trailhead: Amasa Back car park; Slickrock Trail: Sand Flats Road.

Distance // Behind the Rocks: 15 miles (24km); Amasa Back Trailhead: 10 miles (16km); Slickrock Trail: 10 miles (16km).

What to ride // A dual-suspension mountain bike.

Tour // Ride independently, or consult the experts at Poison Spider Bicycles (www.poisonspiderbicycles.com) for guidance, or to arrange a spot on the Porcupine Shuttle, which leaves daily, taking bikers to do the epic 32-mile (51km) ‘Whole Enchilada’.

When to ride // Spring and autumn deliver ideal conditions.

More info // www.utahmountainbiking.com

© ZUMA Press, Inc. / Alamy

navigating the sandstone Amasa Back trail

- EPIC BIKE RIDES OF THE WORLD -

MORE LIKE THIS

24HR MOUNTAIN BIKE RACES

THE 24H OF FINALE LIGURE, ITALY

Moab may have been the spiritual home of 24-hour MTB racing up until 2012, but the format conceived by Laird Knight and taken to the extreme by John Stamstad has spawned many classic events all over the world. One of continental Europe’s biggest all-day bike bashes is the 24-hour of Finale Ligure in Northern Italy. Since its launch in 1999, this iconic race has seen teams and soloists compete on separate singletrack circuits, both with stunning sea views over the Mediterranean. Around the race, the Mountain Bike Festival of Finale takes place, with various bike-related activities, plus entertainment, food and drink.

Start/End // Camping Terre Rosse

Distance // It’s a 4-mile(6.7km) circuit for solo riders, and a 6-mile (9.75km) circuit for team riders.

More info // www.24hfinale.com

THE STRATHPUFFER 24, SCOTLAND