Besides a trip to Puerto Rico to meet his dying grandmother, Roberto had never been out of the northeastern United States. But a mere thirty-six hours after seeing the digital photo on Mr. Ponson’s laptop he was tossing his knapsack and Gulliver’s carrying case into the backseat of a funny taxicab — pale green instead of yellow — at Orly airport in Paris.

“Do you speak English?” he asked as he slid into the backseat.

“Of course,” the driver snapped.

Roberto gave him the street address of Monsieur Pierre Ponson, and off they went. From the way the gruff driver weaved in and out of the airport traffic, Roberto figured the meter must speed up along with the tires. Soon they were barreling down a highway that reminded him more of New Jersey than of the Paris he’d seen in movies. But before long the roadway rounded the side of a hill, and there, gleaming in the bright morning sunlight, were the Eiffel Tower and the spires and steeples of the great French capital.

Soon the driver was slaloming down a grand boulevard bordered by trees with mottled, peely bark and kiosks plastered with advertisements for strange-looking products. Cars didn’t stick to lanes: Driving seemed to be a total free-for-all. Even when the driver turned down a cobbled street far narrower than any in Queens, he managed to swerve around other cars.

The street widened out onto a little square, and the taxi screeched to a halt across from the bakery — it had the word boulangerie in gilt letters on the window — the one from the picture in the Ponsons’ living room. Roberto counted out some of the foreign currency he’d exchanged dollars for at the airport. He had no idea how much to tip over here, so he gave fifteen percent, which got an honest-to-goodness smile from the surly driver.

After the taxi screeched away, Roberto just stood there a moment on the hosed-down cobblestones, carrying case in one hand, knapsack in the other, eyes fixed on the top of the Eiffel Tower, which was visible over the roof of the building opposite. On the overnight flight he’d dozed off about twenty times, and each time he’d woken up, he’d wondered if he’d done the wrong thing in depleting his Hollywood fund to pay the airfare. But now that he was here, inhaling the mingled odors of freshly baked bread and wet stone, gazing up at the famous tower, he somehow knew he’d done the right thing.

A bell over the door tinkled when he walked into the boulangerie. A pretty girl about his age smiled at him from behind a glass case displaying all sorts of delicious-looking breads and pastries. She spoke to him in French.

“Sorry, je ne parle pas français,” he said, using his one French phrase. “Is Monsieur Ponson around?”

The girl turned to a doorway screened with hanging strands of colorful beads and called out something in French. Soon Monsieur Ponson emerged through the beads — instantly recognizable from the photo despite the fact that his dark face and hair were considerably lightened by a dusting of flour. He came around the counter grinning and embraced Roberto as if he were a long-lost member of the family.

“Bienvenue à Paris,” he said. “Welcome to Paris.”

The French Mr. Ponson was far thinner than the American one, which was kind of surprising, considering his profession, and he spoke in a lyrical way that was pleasing to the ear. He called Roberto Robert (Row-bear).

“Robert, I wish you to meet Felice.”

Roberto put down the carrying case and knapsack and offered his hand across the counter. This seemed to take the girl by surprise, but after a moment she reached over and gave his hand a quick shake. Her huge brown eyes, peering out from under clipped brown bangs, had a tinge of purple in them, like Dr. Pepper.

“You must be hungry from your voyage,” Mr. Ponson said. “You will have brioche? Croissant?”

“Wow, thanks. But . . . is Gully really here?”

Mr. Ponson picked up Roberto’s knapsack and led the way to a door in the back of the shop. Roberto grabbed the carrying case and followed the man up a narrow staircase to a sort of garret apartment. The furniture in the living room was pretty modern; on a white formica table, toasters were winging their way across the screen of a laptop. Mr. Ponson motioned to Roberto, who set down the carrying case and followed the man down a little hallway that led to a kitchen. A scrawny Lhasa apso was curled up asleep on the floor by the stove.

“It is him?” Mr. Ponson whispered.

Roberto stared for a few moments, then nodded his head.

“He’s exhausted,” Mr. Ponson whispered. “The first two days he just sit and shiver, but he finally fall asleep. He choose the warmest place.”

Roberto wanted to pick Gulliver up, but the poor dog clearly needed his sleep, so he followed Mr. Ponson back out into the living room.

“How’d you . . . How’d he get here, sir?”

“Pierre.”

“Pierre.”

“It was Tuesday. On Tuesday morning I always take the Turkish bath.” Pierre grinned. “The heat remind me of home, I think. I walk back by the Seine and this dog sits by himself staring down at the water.”

“The Seine?”

“The river, just over there. It go through Paris. So this dog look like the one in the picture François send me. And then I see the collar. This unusual collar, no? So I click my tongue, and he look up. He look at me hard. Then when I turn to go, he follow me. So I give him some food, but he don’t eat. Like I say, he just sit shivering, mostly. I take a picture and send it to François.”

“Could you show me where you found him?”

“Don’t you wish to rest after your voyage?”

“Oh, I’ll find a youth hostel later. First I — ”

“Youth hostel? But you stay here.” Pierre opened the door to a small room with a bed in a nook under a dormer window. “It is not deluxe, but just for you,” he said.

“Wow, that’s . . . thanks.” Carlos had given him two hundred dollars spending money, but it wouldn’t have gone far if he’d had to rent a room.

“Let me wash, and I show you,” Pierre said, setting the knapsack on a chair.

“You can take off now?”

“It is my shop. And I have a very good apprentice.”

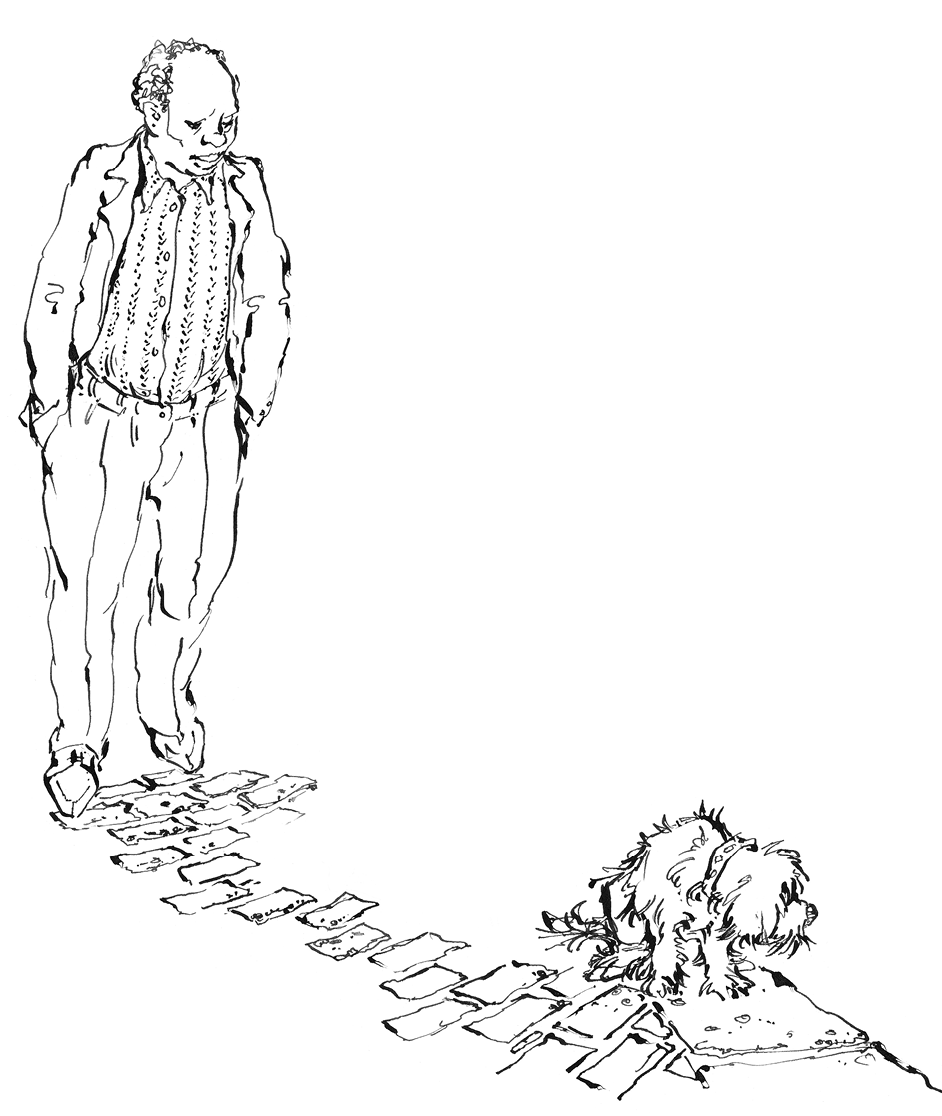

Pierre soon emerged from the bathroom minus the dusting of flour. On the walk to the river, several people greeted him by name, including an old woman sweeping out the gutter with a broom made of twigs. Soon Roberto had his first look at the Quai. Set up by a long stone wall overlooking the river were stalls offering used books and prints and maps for sale. Pierre led the way toward a low stone bridge, but instead of crossing it, he turned down a set of stone steps that took them to a lower riverbank, where several boats were tied up. Two cabin cruisers, a small barge, and a tourist boat called L’Esprit de la Seine with pictures of tourist attractions like Notre Dame Cathedral and the Eiffel Tower painted on the stern. It was by this boat that Pierre stopped.

“The dog was right here,” he said.

A gnarled-up man in a faded blue Breton fisherman’s jacket and a beret was smoking a smelly cigarette on the deck of the tourist boat. When Roberto asked if he spoke English, the man squinted at him and said, “A leeetle, yes.”

“Do you know anything about a dog, sir? A Lhasa apso?”

The man shrugged, mystified. Then Pierre said something in French, and the two of them started an animated conversation that made Roberto wonder if he should have taken French instead of Drama as his elective last year. After about five minutes, Pierre thanked the boatman and led Roberto back up the stone steps to the Quai.

“We have a little lunch, yes?” he said.

“Great. But what did he say about Gully?”

Pierre led him down a side street to what was clearly a very popular outdoor café. They squeezed into rickety metal chairs at a small table, and Pierre ordered something called croques monsieurs and, to Roberto’s delight, a carafe of white wine with two glasses. Best of all, the waiter filled both glasses without carding him.

“You know I’m not twenty-one yet,” Roberto whispered when the waiter sidled away.

“To your first visit to la belle France,” Pierre said, clinking glasses.

The wine tasted a bit bitter, but Roberto pretended to like it. “So what did the boat guy say?” he asked.

“He does tours up and down the Seine. He docks in Le Havre — this is the port at the end of the river — and a dog jump off another boat to his deck.”

“What kind of other boat?”

“A fishing boat. How you say . . . a trawler. He talk to the crew, they are mostly Dutch, and they say they get the dog from another fishing boat, an American one, way off in the Grand Banks. The Americans say they fish the dog out of garbage, in the water near the Long Island.”

After digesting all this, Roberto said, “You think Gully got onto one of those garbage scows?”

“This he did not know. Still, it is quite a history, no?”

A croque monsieur turned out to be something like a ham-and-Swiss sandwich, only grilled and better. But Roberto was too excited to pay much attention to his lunch.

“You’ve got a digital camera, right?” he said.

Pierre nodded.

“And you’d act as a translator for me?”

“I think it is possible.”

A plan was taking shape in Roberto’s mind. He would interview the boatman and snap a photo of him with Gulliver on the boat. When he got home, he would take a picture of the beach at Far Rockaway where Gulliver had vanished. Then he would write up the story to the best of his ability and send it to the woman at the Daily News. And perhaps he could get Pierre to translate the piece into French and interest a Parisian newspaper in it . . .

His eagerness to get started was so plain that Pierre skipped his usual after-lunch espresso. He laughed off Roberto’s attempt to pay the bill, and instead of checking on his apprentice when they got back to the shop, he followed Roberto upstairs so he could lend him his digital camera.

Roberto headed straight for the kitchen. No dog was curled up by the stove. He went back and joined Pierre in the living room.

“He’s not there,” he said.

“Really?”

Pierre clucked his tongue. Gulliver didn’t appear.

“Oh, no!” Roberto cried. “Don’t tell me I came all this way and now — ”

“Was that open before?” Pierre said, pointing at the door of the carrying case.

It hadn’t been. Somehow Gulliver must have managed to open it. For when Roberto squatted down and peered inside, there the dog was, curled up inside, fast asleep.

This time Roberto couldn’t resist. He reached in and stroked the dog’s belly.

“Hey, Gully,” he murmured.

Gulliver opened his eyes. For one ecstatic moment he thought the familiar face actually was Roberto’s. But then he realized he must be dreaming and closed his eyes again.

“Gully, it’s me,” Roberto said.

Gulliver reopened his eyes. Whether he was dreaming or not, the hand on his belly was the nicest thing he’d ever felt. He twisted his head around and gave the hand a lick.