Along the River

On the small airplane heading north, facing the Himalayas, which emerged from the dense tropical clouds, I remembered a book received, at nine or so, from my father’s hands, on a day spent home with fever. It was called The Most Beautiful Mountains and Most Famous Climbs. On the cover was Monte Rosa, my first and only so far. I had already tasted its rock and ice in the summer, but by winter the mountain had become a distant memory, so I spent long hours in bed with that book of color photos, to cure myself of the flu and nostalgia. I looked at the profiles of Everest, K2, and Nanga Parbat, I read about the men who had climbed them, I learned names and altitudes with the doggedness of a child for whom memorizing is a magical act that offers the illusion of possession. I dreamed of becoming a mountaineer then, reading about Messner and Bonatti as if they were Stevenson and Verne, and Tibet and Nepal were secret kingdoms, treasure islands.

Thirty years later I still knew the shape of Dhaulagiri, the westernmost of Nepal’s eight-thousand-meter peaks. The airplane flew below it, grazing the puffs of clouds lit by the sun, and left it to the east. Other dark peaks emerged in front of us, a chain of them at about five thousand meters. As we had hoped, the fog stopped against that wall. Then under the propellers I began to observe sharp ridges, gorges that dropped into the morning shadows, gullies dug by landslides in the rainy season. I looked at Remigio glued to the porthole and thought I knew what he was looking for: a landscape he could read, a script he knew.

Ever since I had gone to live in the mountains, the valleys had begun to interest me more than the peaks, the inhabitants more than the climbers. I was fond of the idea that there was only one great people in the highlands of the world, but that was just romanticism; in the Alps we were now citizens of the immense European megalopolis, or of its wooded periphery. We lived, worked, moved, had relations like city dwellers. Did mountain people still exist? Was there an authentic mountain somewhere, free from the city’s colonialism, its integrity intact? This was the spirit in which I had gone to Nepal a few years earlier. I had toured the most popular areas only to discover that even in the Himalayas modernity was bringing its gifts: roads, engines, telephones, electricity, industrial products, the blessed well-being desired in exchange for an ancient culture, poor and destined for extinction, just like alpine culture. I had to look harder, go farther.

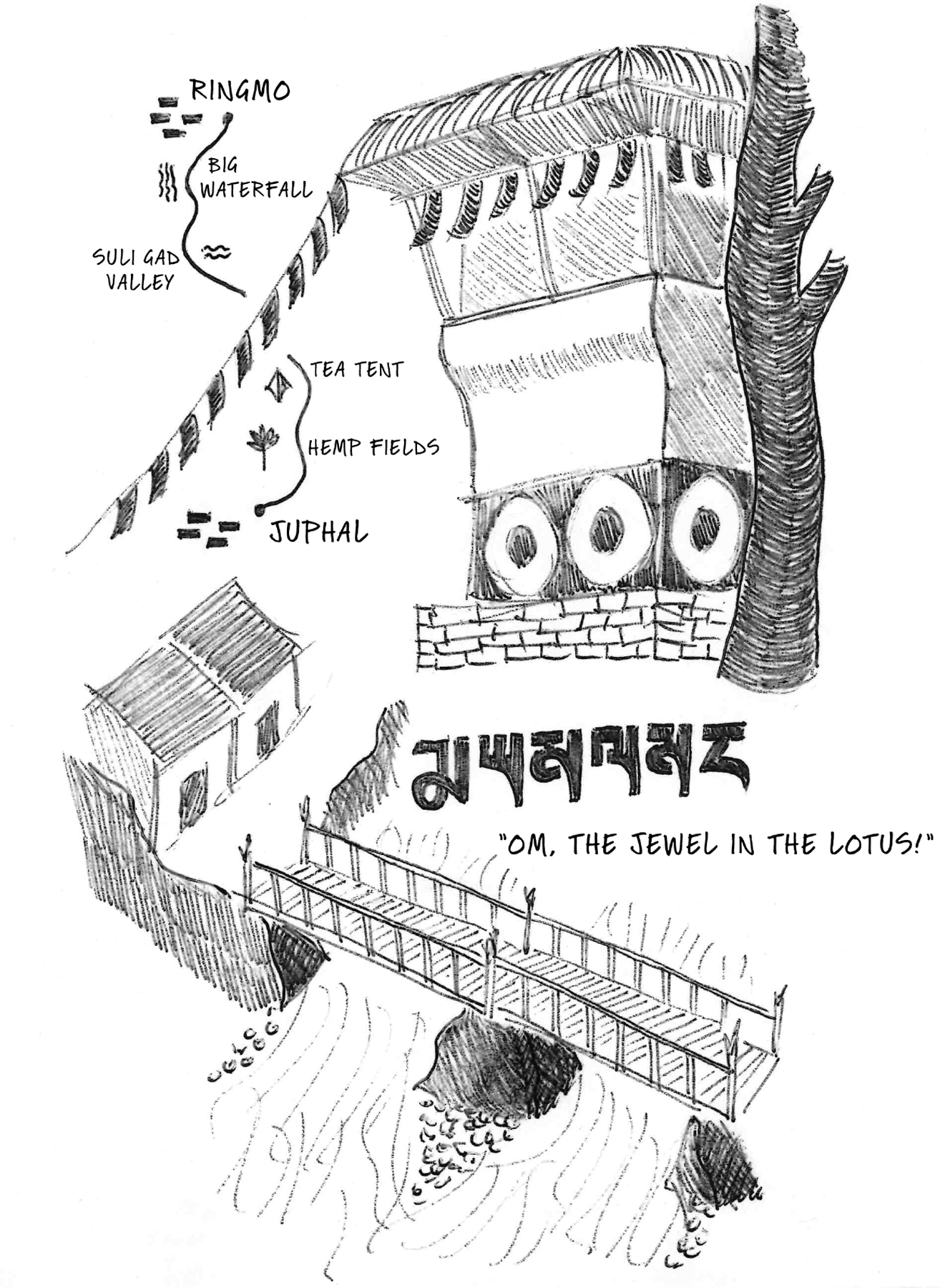

The pilot whose moves I was watching veered gently, following the lines of a valley in the sun. He zeroed in on a short dirt runway, no more than a hundred meters in the middle of a slope, and lowered us for landing. We touched down and braked between the houses of Juphal, the beginning of the long trail to the north: low stone huts, terraced fields all around, almost ready for harvest that season. I still had the sweat of a sultry tropical morning on me, and as I climbed down the stairs I immediately felt the clean smell of the mountain. In the time it took to collect my rucksack the twin-engine had already taken off.

Sete was forty-seven, a Tamang from eastern Nepal. Wide cheekbones, narrow eyes, brown skin, he had been loading wicker doko baskets on his back since he was a boy. After becoming a cook and high-altitude porter, and having climbed Everest, Makalu, Cho Oyu, Dhaulagiri, and Shisha Pangma in that capacity, he too had descended into the valley with age. Now he worked summers and winters in the Monte Rosa shelters, and in the fall he worked as a guide for exploratory expeditions such as ours. He spoke Italian and laughed often. I wondered if it was an innate joy or one of the tricks of the trade, a way to avoid direct questions. He had been in Juphal for a few days already, putting together the caravan, which consisted of him, his brother, five boys working in the camps and the kitchen, five others with animals and transport, and twenty-five mules laden with all we could use in nearly a month of walking. Plus the ten of us coming from the Alps made forty-seven animals and men. Tents, equipment, food, kerosene for cooking, mule feed, and personal baggage were loaded onto the packsaddles. The only thing we didn’t bring was water: finding a stream every night and the space to camp was Sete’s task; he had never been to Dolpo but had little faith in our maps. He preferred to ask muleteers and passing peasants for the way. It was hot in Juphal and I was trying to figure out what to bring in my backpack and what to load onto the mule, so I asked him when I would need heavy clothing.

“Higher up,” he said.

“What do you mean by ‘higher’?”

He pointed distractedly to a Y-shaped stain on the map I had laid out, the big Phoksundo Lake lying between two valleys.

“And how long will it take to get there?”

“Four days hopefully.”

“Hopefully?”

I checked the altitude of the lake: thirty-six hundred meters. At twenty-five hundred, where we were, corn was growing. Descending from Juphal to the valley floor we crossed rice fields, terraces planted with barley and millet, and lush vegetable gardens. The houses had flat earthen roofs on which hay and chili peppers dried out. Much of the life of the village seemed to take place up there, and it was all female: young women beat barley with long sticks, the old women winnowed it in the breeze that carried away the chaff; below, in a stone basin, a little girl was washing her hair with laundry soap. Elongated yellow gourds, strange peas with thorny pods, even bunches of cherry tomatoes populated that treeless slope, where only the Himalayan cedar, a conifer that had an African air to it, produced shadows between the gardens.

Looking around me, I thought of the terraces invaded by brushwood, the dry-stone walls in ruins, the irrigation canals swallowed by forests, which I used to see in the Alps. I thought about when our mountain was just as well cared for and when this one would experience abandonment. Was it a road I saw down there? Yes, there was a dirt road alongside the river and just as we reached the road we passed a small truck; a couple of years ago, as far as they told us, there was only one mule track there.

At this news I exchanged glances with Remigio. He was born in a village where until the seventies you had to climb up to it on foot; then the road came and he saw the village empty out entirely during his life. Once he told me: when the road comes it always seems made to bring things in, but then you realize it was made to take things away. He was watching two workers fixing the road with a shovel and pickax. I think he was reliving a scene from his childhood.

The caravan kicked up dust and the river’s freshness started calling me from down below: when Sete picked a spot for setting up camp, I was the first to take off my shoes and dip my feet in the turbulent water of Bheri River. It was turbid and metal gray, from a glacier.

“Where does this water come from?” I asked.

“From the mountain.”

“What mountain? Dhaulagiri?”

“Hopefully.”

Sete would say “hopefully” instead of “maybe,” and this gave his replies a strange oracular tone. Wherever the water came from, I had studied the maps and knew where it wound up: in the Karnali River, whose source was in Tibet; then after seven hundred kilometers it poured into the Ganges. Sitting there on a boulder, among the gnats and ferns, I told myself that my feet were soaking in the water of the sacred river.

“You’ve already been up there, haven’t you?”

“Where?”

“On Dhaulagiri.”

“Yes, that’s right.”

“How was it? Do you remember?”

“Long,” Sete said. Then he went into the kitchen tent to supervise preparations for dinner.

I lay down to dry myself in the sun and took out the book I had brought with me from the bag. It was The Snow Leopard by Peter Matthiessen, published in 1978 and still on the shelves of every bookstore in Kathmandu, where worn paperbacks passed through the backpacks of new trekkers. That book also had something to do with my journey. In fact, it had partly inspired it, because I would be retracing a good section of the path described there. We were the same age, The Snow Leopard and I, though it may have only been a coincidence. I was now reading it for the second time.

From what I knew about him, this Matthiessen was quite likable: born in 1927 in New York, in the fifties he was part of the second generation of American expatriates in Paris, emulating Hemingway and Fitzgerald, with less luck. He also had a young wife, an apartment on the Left Bank, and notebooks to fill. Although he never produced anything memorable in France, he had been one of the founders of the historic literary magazine Paris Review before going back home to cultivate two passions: naturalistic studies and the exploration of the psyche. Impatient with domestic life, he soon divorced and started traveling. In the sixties he became an environmentalist and traveled far and wide in Latin America and Southeast Asia. He had explored the cultures of the natives and experimented with peyote, ayahuasca, mescaline, then a longer phase with LSD, keeping accurate accounts of his experiences. Finally, like others, he wound up dabbling in heroin. The seventies with their failed promises disappointed him, or perhaps he was his own source of disappointment, entering midlife with the realization that he had accomplished little. He grew tired of hallucinogens, became interested in Buddhist practices. He continued to write without great results.

From his point of view, it was the evolution of a quest. Then his second wife, with whom he had been on-again and off-again for some years, fell ill with brain cancer and died shortly after. Peter found himself a widower, the father of a small child, and lost in many ways. The invitation of a zoologist friend who would be going to Nepal to study the behavior of the bharal, the blue Himalayan sheep, came providentially. The destination of the expedition was Shey Gompa, the “Crystal Monastery” in the heart of Dolpo, where hunting was forbidden by the local lama and the wild bharal proliferated. With a little luck, their main predator might be seen, the elusive snow leopard, that “most mysterious of the great cats,” which has never been observed by anyone, or almost. Wouldn’t that be a good way to start over, or at least make a perfect escape? Matthiessen left his son to a couple of friends and departed. Here “was a true pilgrimage, a journey of the heart,” he wrote, to “the last enclave of pure Tibetan culture left on earth.” With these lines and a map drawn by hand began the diary that would bring him fame. As had happened to me before, I stumbled upon the book a little too late to know its author: Matthiessen had died in 2014, almost ninety years old, a tall, thin old man with a marked face and very light eyes. I looked at them in a black-and-white photo that I used as a bookmark and they seemed so clear to me, eyes without shadows, without secrets.

I also liked drawing maps. I would keep a journal like his, during moments of rest jotting down observations in a black notebook I had brought, strong but soft enough to fold and put in my pocket. I inaugurated it that evening. While I was finishing my notes for the day they called me for dinner: the first meal of rice and lentils in the mess tent, the first night in the little pup tent. I entered it together with the book, the pen, and the notebook, with the roar of the water that flowed by my head.

Nicola was lying in his sleeping bag next to me, an intimacy I would quickly get used to. Besides, he and I were constantly discovering surprising similarities between us: not only had we been born a few hours apart, but the same went for our fathers as well. We had both grown up in Milan (he just outside), spent some time in New York (he lived in Harlem while I lived in Brooklyn), and fled to a mountain cabin (he to Valtellina, me to Valle d’Aosta), and had never met until a year earlier, when we immediately recognized each other. We had lived parallel lives, and a dialogue in our tent could sound like this:

“Do you remember that November, the night of Obama’s election?”

“Sure, I was on the Lower East Side, listening to a concert, a black trumpet player who wept as he played.”

“In Harlem the women were hugging each other on the street. It was like witnessing a revolution.”

“Then not much changed, though.”

“But it was beautiful just to be there.”

After all, I thought, we are the Matthiessens of our times. There was enchantment and disappointment in our New York, just like in his Paris. I had written tales of sailors while sitting on a Brooklyn pier, Nicola had started painting people walking while looking out at the Harlem avenues from his window. Later he painted the people from the mountains, more curved, always from behind, as they returned from the fields with their tools on their backs.

“Are you sleepy?”

“Not at all.”

“I feel like I’m in my mountain cottage again, when the nights never end.”

“But in the cottage I have grappa.”

“In mine there’s whiskey.”

“You feel like reading me something?”

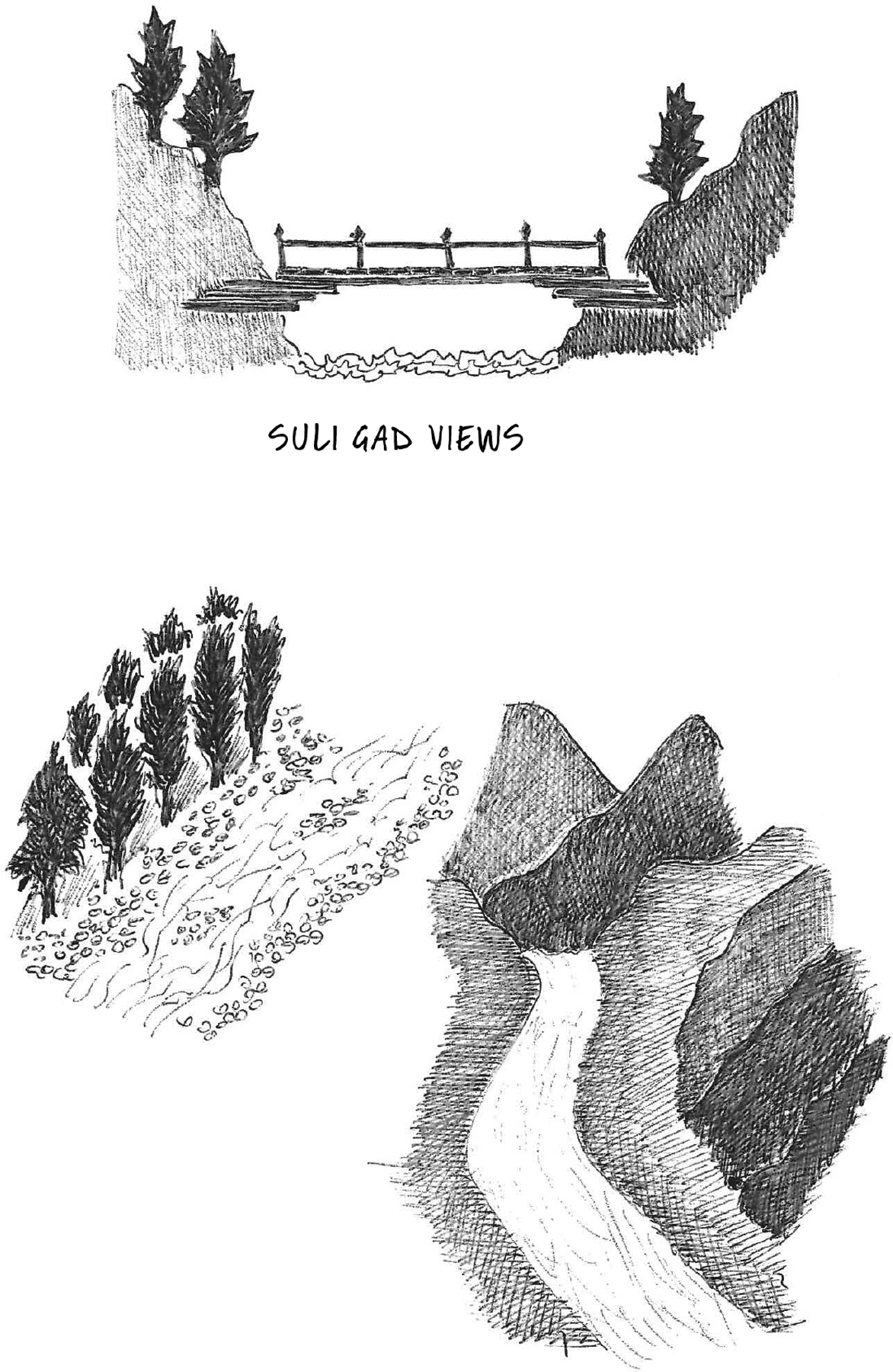

There we were, a painter and a writer. He was left-handed and I was a righty; we divided the sides of the tent, so that the good hand could take what it needed. In my case the book, the caravan’s third forty-year-old. I read aloud to him: “Listen here: ‘I wonder if anywhere on earth there is a river more beautiful than the upper Suli Gad in early fall. Seen through the mist, a water spirit in monumental pale gray stone is molded smooth by its mantle of white water, and higher, a ribbon waterfall, descending a cliff face from the east, strikes the wind sweeping upriver and turns to mist before striking the earth.’” After a few lines Nicola was no longer listening to me. Often Matthiessen’s hallucinatory visions lulled him to sleep suddenly, so I said good night and went on reading in solitude.

Matthiessen had used a very specific word for his journey: “gnaskor, or ‘going around places,’ as pilgrimages are described in Tibet.” A pilgrimage is a path of purification in every culture, but in going around places there is no point of arrival, which is fundamental for pilgrimages as we meant them. Jerusalem, Rome, Mecca: without a destination, how do we know if we have been purified? I found a connection between this need for a holy city at the end of the journey and the mountaineering obsession with mountain peaks: ever since I was a child I felt I used the summit as a metaphor for heaven, and the word “ascent” in a spiritual sense. Whereas I remembered that the most important Tibetan pilgrimage consists of going around Mount Kailash, which for that culture is sacred. Kora in Tibetan, “circumambulation”: Christians plant crosses at the tops of mountains, Buddhists circle around them. I found violence in the first gesture, kindness in the second; a desire to conquer as opposed to embrace.

My pilgrimage began with a suspension bridge, steel cables pulled from one side of the river to the other, which led into the Suli Gad gorge, leaving the last road behind. For many days we would no longer see motor vehicles. We went up a narrow and arid valley, with the frothy stream below us and the lammergeiers circling above our heads, stopping to watch us from the cliff faces. Where the vegetation reappeared, we entered among tall plants that took me a while to recognize from the leaves. The scent was familiar. Was it possible? Hemp grew everywhere around us, very high, thick, luxuriant, near the deserted winter stables we came upon, on the land fertilized by dung. I noticed the mules grazing on it happily. I snapped a leaf off and slipped it into my breast pocket like a flower, thinking of Matthiessen and the hippie motto I’d seen on some T-shirt in Kathmandu:

NEVER

END

PEACE

AND

LOVE

“You see?” Remigio said. “They’re making hay over there.”

He pointed to the other side of the gorge where some women were working, bent over with small, thin sickles. The two of us had also spent hours in the fields, among mowers, tractors, balers, and trailers loaded with loose hay on which I sat while he drove. This was why the Nepalese technique interested us: here they took it away in their doko baskets, along a path that cut the slope and disappeared over a ridge. There must be a village back there, we told ourselves, and we wanted to know what it was like. We still couldn’t see any men, only very small boys, little more than children: they had formed a human chain to pass a jerry can of water that the first had filled in the stream and the last would carry around to quench the mothers’ thirst.

The shade of the forest welcomed us like a blessing. The hay was hung to dry on the branches of the cedars and pines, in long braids similar to lianas. On a rock wall I saw the mantra Om Mani Padme Hum painted, six symbols I had learned to recognize and a sound I occasionally heard being chanted: “Om, the Jewel in the Lotus!” A mysterious verse open to a thousand interpretations, which alludes to the unseen hidden within the seen. Outside there is the lotus, the form, the transient; within it, there is the jewel: the precious substance, which endures. What was hiding in those braids of hay? What was in the flight of the lammergeier, in a wild pear tree in the middle of the woods? I cut a hard and unripe fruit from it, chewed it, but it puckered my mouth and I had to spit it out. I wanted to apologize to the tree.

In the afternoon, freed from the packsaddles, and perhaps still under the effects of cannabis, the mules rolled joyfully on their backs, scratching away the burden of the load. I watched the porters and the mule drivers: they were boys of about twenty, wearing jeans and sneakers with thin soles; under the doko baskets they had curious eyes and attempts at fashionable hairstyles. They set up camp next to a small house with an outdoor table, two benches, a pile of empty bottles, a drying rack from which I intuited that the cannabis all around was a comfort the inhabitants of the valley appreciated; I preferred beer and went in to see if they had any. In the house, which looked like an emporium, or maybe it was a bit of both, a woman in broken English asked me where we were heading.

“Phoksundo,” I answered, pointing at the window. “Shey Gompa. The Crystal Mountain.”

“It’s far,” she said, holding out a bottle of beer that had a raised brand on the glass and a different one printed on the label. A Heineken that somehow had become an Everest. The woman refrained from asking the next question, which was why do we Westerners come so far to toil, sleep on the ground, suffer the cold, and be covered in dust with no apparent purpose but to turn away from our warm beds and fast cars, but I could read it in her face. If she had had the words to formulate it, would I have found the ones to answer?

At sunset, as I sipped my Everest by the river, I discovered that Matthiessen had had a similar encounter. But he had actually been asked: “I shrugged, uncomfortable,” he wrote. “To say I was interested in blue sheep or snow leopards, or even in remote lamaseries, was no answer to his question, though all of that was true; to say I was making a pilgrimage seemed fatuous and vague, though in some sense that was true as well. And so I admitted that I did not know. How could I say that I wished to penetrate the secrets of the mountains in search of something still unknown?”

I put the book down and looked at Suli Gad. As the sun set, a smell of moss came down the valley along with the water. Even without knowing what you are looking for, I thought, a stream is the best way forward: it always points out the direction, you go up toward your own source, and as you see it become clearer you feel yourself becoming purer as well. I imagined the big Phoksundo Lake reflecting the glaciers from which it was born. I immersed my hand in the icy water and it seemed like a promise of that snow.

That old hippie was right. I had never seen anything like the Suli Gad valley either. I walked alone, occasionally crossing a companion, and I lost myself in the contemplation of water. Along the river the shapes struck me with such force that I often sat down to draw: Himalayan cedars, pines that looked like the Arolla pine, birch trees with yellowed leaves. A bridge made of logs stuck in the banks and jutting into the void, the posts of the railing carved by a skilled woodworker. A pile of mani stones, large river rocks on which mantras for the village’s protection were engraved (Sete advised us to always pass to the left of such shrines, respecting the clockwise direction that governs the universe for Buddhists). Corn cobs on the roof of a house and a woman stirring fermented barley in a cauldron, from which she would make chang, a kind of murky beer, or rakshi, the raw distillate the Nepalese imbibed to get drunk. Then puddles, rapids, shores of white gravel, islets of ferns, sandy bends. Two women riding a mule passed me while I was drawing.

I thought I heard them laughing or maybe it was a trick of the water, the mirth of a waterfall. Matthiessen: “I look about me—who is it that spoke? And who is listening? Who is this everpresent ‘I’ that is not me?

“The voice of a solitary bird asks the same question.

“Here in the secrets of the mountains, in the river roar, I touch my skin to see if I am real; I say my name aloud and do not answer.”

Going up the stream, I came across a square-shaped tent, made of thick military green canvas, with a pair of windows and a hole at the top, from which a blackened chimney protruded. Remigio was there waiting for me. Outside the tent, a boy was splitting wood from a cedar trunk, a horse tied to a tree chased flies away with its tail, a baby with a sooty face stared at us.

“That’s me when I was seven,” Remigio said.

“What did you do when you were seven?”

“In the summer I would go up to the high pastures with my mother. We had a stable and a common room where we ate and slept. In the seventies the first tourists passed by on the path. They were curious, but I was ashamed because I was always dirty, and because of the life we were living.”

The boy didn’t know he was facing his future self; Remigio smiled at him and he ran away. I, on the other hand, began to understand that all those mountain people were half shepherds and half merchants, so I looked into the tent to ask if we could have tea. I was right: a girl made us sit on cushions around the stove in the warm and smoky darkness and put the kettle on the fire. As we waited I looked above me and noticed strips of meat hanging to dry on a wire. From the smell I assumed it was a goat. Pots, jars, rice bags, rags, basins, and cups littered half of the tent at ground level.

“Everything on the ground, just like in my mom’s kitchen,” Remigio confirmed.

I put my lousy Nepalese to the test with the girl, who could have been the boy’s sister, though more likely his mother. She must have been twenty years old. Tato pani: hot water. Mito tsa: good! Didi: girl. Ramro didi: beautiful girl. She smiled and poured me another cup of her black tea with powdered milk and juniper smoke.

The first snow appeared in the late afternoon at the end of a lateral valley: a peak from the Kanjiroba Himal, a chain that rises to nearly seven thousand meters, shone above the dark slopes when the sun no longer reached us. It reminded me that woods, streams, and valleys were just preludes to what was awaiting us, and my mood changed. After lingering a bit to write and draw, I was relieved to find my companions. Our row of pup tents was already set up near a village, mules grazed, and the smell of soup came out of the kitchen. I sat at a table with the others, and while they were chatting, I checked the map: it said that Sanduwa, where we were, was at 2,960 meters.

“Is everything all right?” Nicola asked me, handing me a bottle. He’d managed to get more beer, vintage Everest straight from the cellar.

“Yeah, sure,” I lied.

“Tomorrow we start climbing.”

“It’s a pity to leave the river.”

“Yeah, it was a beautiful river.”

We toasted to Suli Gad by clinking the bottles. Nicola noticed something was wrong, but I didn’t want to explain it to him. Anyway, there was plenty of time for him to figure it out by himself.

I never could have become a mountaineer. As a young boy I soon discovered I was susceptible to altitude sickness; my stomach was a merciless altimeter: it would start to turn on me after three thousand meters and torment me to the summit at four thousand, where I arrived foggy, often vomiting, so all the beauty of those mountains was lost on me, and what remained was just a feeling of hard-won conquest. For years I returned hoping that at a certain point the sickness would pass, but it didn’t. To make up for it I started to become familiar with it. I knew when it was coming, and I learned that it would disappear if I descended. It became part of my going to the mountains, with my mind insisting, spurring, cajoling; the body obeying with difficulty and imploring me to go back, until the day when I’d had enough of that struggle and it struck me as absurd to keep fighting. Mountaineering could have remained a childhood dream. If the glacier pushed me away, there were always meadows and woods that would welcome me gladly. I hadn’t climbed above three thousand meters in more than twenty years.

Not until I got to Sanduwa, where the valley forked: the village of Murwa and the last cultivated terraces to the northeast, to the northwest a deep canyon hollowed out below by the Suli Gad. I let the others go ahead and I was left alone. In front of me, beyond the canyon, there were badlands with precarious boulders balanced above high red pinnacles and jagged furrows caused by runoff in between; the water gushed from the bare earth in several places, as if it were emerging from a landslide. Which was what actually happened, the great primordial landslide from which Phoksundo was created: where the valley closed, the path became steep, climbing for the first time after days along the banks of the stream. All around, the forest that had protected me until now was reduced to dwarf cedars, thorny bushes, dog rose shrubs, dust-gray junipers.

On that slope my old altimeter kicked in again: 3,300, 3,400, 3,500 meters. My lungs felt the impoverished air, my alarmed heart began to beat too fast, my stomach contracted. I slowed down. If I’m suffering at 3,500 meters, I thought, how will I get over the 5,000-meter passes? I tried not to think about the future, the other 1,000 or 2,000 meters of altitude difference, and to concentrate on controlling my feet, legs, and lungs so that they wouldn’t get into trouble, so I could keep my breath deep and regular instead of panting. I could keep my stomach down only if I stayed calm. Calm was really the key to everything, the true opposite of fear. Preoccupied with this interior work, I hardly noticed the point where, beyond me, the canyon ended and the majestic Suli Gad waterfall appeared: the water exploding halfway down the slope and falling white with foam, then flowing joyously toward the distant Ganges. I would have liked to take a bit of its lightness and soak up some of its strength for the days to come.

Finally, after passing the landslide, the path entered a hollow and eased up. Around me the sound of water vanished and pine shade reappeared. I saw new mountains on the horizon, these covered with glaciers, and pastures still green at their feet; in the pastures isolated black spots roamed, the first yaks of the journey. I spent whole summers living among the high mountain pastures in the Alps, and the grazing beasts made me feel at home. So did the soft green of the grass, the deeper green of the Himalayan pinewoods, and the gentle shapes of the peaks. Two large red-and-white chortens, similar to three-story pagodas, acted as a gateway to that world; as I passed them I came across a girl who was running. I was slow, heavy, absorbed in my controlled pace, whereas she was so light that the breeze of her run tousled her long, black shiny hair flowing over a burgundy dress and embroidered wool belt.

“Namaste!” I greeted her in Nepalese.

“Tashi delek!” she answered in Tibetan. From her language, the dress, those swift feet, and her Mongol features, I could see we were already over the border. The two chortens stood on a hill and as I approached the top I saw the houses of a village and, a little farther, at the bottom of the valley, the blue of Phoksundo Lake. Not the turquoise I had read about but the oil of my mood. Or was it just the sky clouding over?

Sete found us a bed by about noon. After a few nights in a tent and the prospect of who knows how many more with the Dolpo earth under our backs, it was not bad to be able to sleep on something soft and get some rest. So I spent the afternoon clearing my mind and walking around the village. But then I saw that Ringmo was more than a village; it was a real town from which caravans left for the north. Yaks, markets, and merchandise were everywhere, as were prayer flags. I looked at the square and flat houses, the stone walls, the small windows with their frames painted light blue, the piles of wood and the haystacks on the roofs. It was a language I recognized: even in the Alps the light blue of the windows keeps flies away, or at least that’s what they believe, and with the coming winter, hay and wood are these highlanders’ gold. In a courtyard, some carpenters worked pine trunks using primitive planes, squaring them to make construction beams. A woman sitting under a portico spun sheep’s wool with automatic gestures: the spindle in the right hand turned, the left unraveled the wool, the hands moved without looking; similar to those of the monk repeating his mantra with a mala in his hand during the puja, the blessing ceremony of a new home. There were three under construction around the country. The owner of an emporium told me that they were not houses but hotels, and although the news worried me, I found them beautiful, all in wood and stone, with beams and handworked panels. New hotels were born from the woods and rocks, old chortens crumbled back into the mountain. Even the stairs that went up to the roofs were carved out of the trunks, like pirogues. Remigio and I went to study them with the idea of building one on our return. The wind was blowing and tattered flags waved on every roof.

“Do you feel the altitude?” I asked him as we did a rough measurement of the stairs.

“I think so. I have a bit of a headache,” he said. Even though he was born at eighteen hundred meters, it was the first time in his life that he had been this high.

“Remember to drink a lot. Water, tea, soup, drink even if you aren’t thirsty.”

“Okay.”

I wanted to go and see the lake and postponed the need to lie down and sleep a while longer. Crossing a suspension bridge, I recognized a boulder Matthiessen had described, with Om Mani Padme Hum painted on it in the middle of the stream. I was impressed that after forty years it was still there, but the ruined monastery on the shore was maybe four hundred years old. A yak herder dozing in the bushes opened one eye as I descended toward the water. Two sensually curved Buddha eyes painted on the wall of a chorten also watched me through the trees. Which of us was watching, which was being watched?

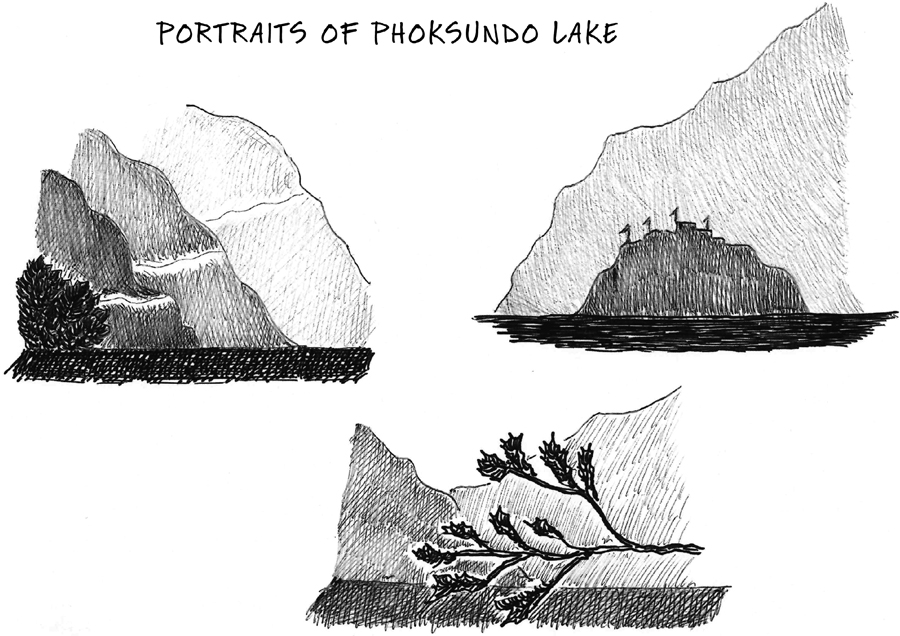

I sat down under a juniper tree full of ripe berries and picked some of them for no reason. I put them in my pocket thinking that sooner or later I would figure out why. From where I was Phoksundo appeared endless, extending out and eventually forking between very high rock walls. According to Matthiessen, who had collected local legends from there, no fish had ever lived within it, nor had any boat skimmed its surface, which made it even more gloomy in my eyes. As much as I had always liked the swirling water of streams, motionless mountain lakes disconcerted me. I tried to make friends by sketching glimpses of her in my notebook. My line was unsteady, my hand trembled, and I had to accept that I didn’t know how to draw the branch of a protruding pine that lapped the lake’s surface, or the rocks emerging like archipelagos, or the ruined monastery. I focused on an idea: that the lake reflects everything, so it is made of what is reflected in it, like me at that moment. It is the only straight horizontal line in a landscape where everything is slanted, curved, broken, irregular: perhaps this was what disturbed me. Or maybe these were just distorted thoughts from the nausea that had invaded me.

I knew from Matthiessen that Tibetans believe the mountain is inhabited by spirits—not evil spirits, but nevertheless harsh with humans, and I must have met mine. “Tibetans say that obstacles in a hard journey, such as hailstones, wind, and unrelenting rains, are the work of demons, anxious to test the sincerity of the pilgrims and eliminate the fainthearted among them.” I also knew that that demon would accompany me for the rest of the expedition, and I was willing to show him my sincerity.

It was strange to be at thirty-six hundred meters and feel like I was at the starting point, but the valley through which we had been climbing for days was suddenly forgotten; from where my eyes were I could only look up. From west to east, a crown of glaciers loomed above the basin. I had the feeling of having accessed another world: I scanned the landscape for ways to get around the lake and saw a trail carved out of the rock that went up the western shore, climbed up a promontory, then descended, or so I thought, somewhere else I couldn’t see, toward Shey Gompa and the Crystal Mountain. There, where only the imagination could go, was tomorrow’s way.