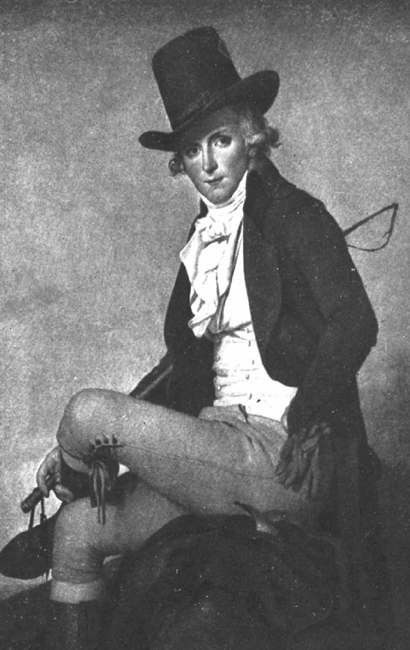

Portrait of Pierre Seriziat (Jacques Louis David, 1795). The cut-away redingote, formhugging suede buckskins, top boots, tall hat and pristine neckcloth spoke of a bolder, faster lifestyle more natural in the fresh air of the countryside.

FOR MALE FASHION it was the ‘battle between broadcloth and silk’ as Balzac had termed it in 1798, and the broadcloth had triumphed. Gone were the old prim white stockings and buckle shoes of the eighteenth century; the mannered ennui of pretty silks and vile gossip was overtaken by young men who stepped in with fresh air clinging to their clothes and mud spattered on their boots. Their style and virility spoke of a bolder, faster life more natural in the fresh air of the countryside. Casual yet suave, the riding coat or redingote became the central piece of the male wardrobe. It could be singleor double-breasted, either tapering towards the back in the style of a morning coat (which remained the more formal), or the sporty square ‘cut-in’ coat with the front amputated below the waist to leave only tails at the back. This became the norm for informal ‘undress’ after 1810 and was, with longer tails, the style preferred by the Dandies.

Where neckcloths became hugely important, shirts were not regarded as such and were one of the sewing tasks assigned to female relatives rather than professional tailors. In November 1800 Jane rushed to complete a batch for her brother: ‘I have heard from Charles, and am to send his shirts by halfdozens as they are finished; one set will go next week. The “Endymion” is now waiting only for orders, but may wait for them perhaps a month’. In Mansfield Park Fanny Price works diligently to ensure that her brother’s linen is ready when he goes to sea, and in Northanger Abbey Catherine Morland is supposed to be making cravats for her brother but finds other activities far more interesting.

Breeches, the staple of the eighteenth-century wardrobe, were increasingly neglected in favour of more comfortable sporting wear. As they made an aristocratic statement they were sidelined into formal ‘full dress’ and remained the only garment acceptable at Court, at the smartest Pleasure Gardens, and also the prestigious Almack’s Club.

The name derived from the character from commedia dell’arte, the ‘Pantalon’ or pantaloons became the forerunner to trousers. Pantaloons were considered so worryingly revolutionary that in 1807 the Russian Tsar had troops set up roadblocks to examine travellers’ leg wear, and anyone discovered wearing them had their pantaloons forcibly cut off at the knees. Related to the tight buckskin breeches worn for riding by English gentlemen since the mid-eighteenth century, they were frequently made of a semistretch fabric like stockinette or were bias cut, the skin-tight pantaloons giving the virile look of a classical statue. Worn with knee-length half boots or Hessians, pantaloons came to mid-calf and were tied with ribbons at the sides.

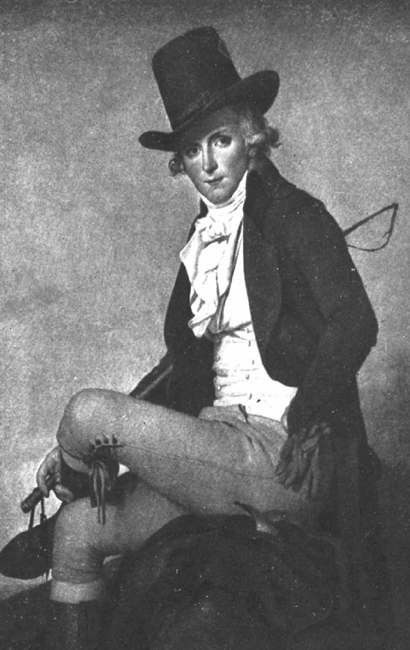

Journal des Dames 1790. The redingote at the beginning of its evolution; worn in bold striped silk with breeches and buckle shoes, it still retains the old refined formality.

Young Gentleman on the Grand Tour 1812. The redingote having reached its Regency ideal; the practical lines and practical fabrics equipped the gentleman for a new era of action.

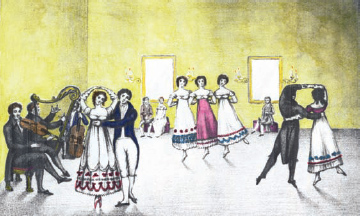

Le Bon Genre, c. 1810. Double-breasted waistcoats with shawl collars became popular in the 1790s and remained so into the second decade of the nineteenth century. Tied at mid-calf, pantaloons could be worn as they are here with striped stockings and modern lace up shoes, or with boots.

Boots were the democratic ideal, taken up by the Parisian bon ton; the English boot reigned supreme for its superior quality and fit. The most fashionable were the ‘top-boot’: worn with breeches and buckskins and looking like a riding boot, they were black knee-length leather with a light coloured top. Worn with pantaloons and inspired by the uniform boots worn by the Hussars, Hessians had a high curved front reaching just below the knee where the ‘V’ shaped notch was decorated with a hanging gold tassel, or silver for mourning. Also to be worn with pantaloons, Hussar boots or ‘buskins’ resembled short calf-length Hessians but without the tassel. After 1819 the Wellington boot was added to the available repertoire – named for the Duke, they were very similar to the top-boot but without the coloured turnover.

Tom and Jerry Sporting a Toe among the Corinthians at Almacks (Life in London by Pierce Egan, 1822). Nothing less than formal ‘full dress’ was acceptable at the prestigious Almack’s Club, as the Duke of Wellington discovered to his chagrin when even he was turned away for wearing trousers in 1814.

Previously, hats had been confined to the tricorne model, but even though highwaymen had managed, they were impractical for riding to hounds as they were apt to fly off at high speeds. A high crown was useful (if scant) protection against head injuries, and also had a nice status look. The receding brim and growing crown which combined in the round hat eventually grew into the top hat.

An Evening at Frascati, 1809. For Court or evening wear the opera hat or cocked hat resembled the military bicorne (see gentleman background left). It was worn with the points to front and back like Nelson rather than side-to-side like Napoleon. It was a chapeau bras, most frequently tucked under the arm rather than worn.

This full dress evening gown with asymmetrical Grecian style tunic from 1811 shows that the romance with Neoclassicism continued unabated.

The divergence of the lives of men and women was marked entirely by their clothes: when they both wore silk and lace and habituated the same drawing rooms, they shared courtly love or gossipy intrigue. With the advent of the nineteenth century, if they weren’t at war or at sea, gentlemen were eyeing horses at Tattersall’s, racing curricles, or were at their club. The only time they would really interact with women was in the evenings at the theatre, opera, Pleasure Gardens, or dancing, where formal full dress of the old order was required.

Although women’s styles were simpler there were still the demarcations of ‘full dress’, ‘half dress’ and ‘undress’ that ruled the propriety of fashion, and English etiquette was set almost like a trap to pull rank on newly moneyed arrivistes even if fashions were more democratic. ‘Undress’ or déshabillé referred to simpler gowns worn at home in the morning, often with a cap. Made of warmer, more practical materials, they would often be looser and more comfortable for sitting writing letters, sewing or reading. ‘Half dress’ covered smarter more formal ensembles for activities such as afternoon promenades, visiting, or even trips to the opera. ‘Full dress’ was the most formal, the most ornate, and had the lowest décolletage. Worn for balls, Almack’s, the premier Pleasure Gardens, and the most luscious parties, it was also the correct wear for attending Court, where it was worn with a headdress of upright ostrich feathers.

‘Morning Dress’ (La Belle Assemblée, 1814). Domestic bliss: mother and baby in matching white ruffles. Her cap is trimmed with pink ribbon, and her bodice has pink ‘braces’ that cup the bosom giving extra support.

Whereas gentlemen’s clothes changed to reflect their changed lifestyle, the most significant changes for women were to the silhouette. Although in Paris the high-waisted silhouette was lauded as the apex of the refinement of classical antiquity, in England the ‘waist-less gown’ was frequently greeted as an abomination especially by male commentators – as in the satirical song, Shepherds, I Have Lost My Waist:

Shepherds, I have lost my waist, Have you seen my body? Sacrificed to modern taste, I’m quite a hoddy-doddy! For fashion I that part forsook Where sages place the belly; ‘Tis gone – and I have not a nook For cheesecake, tart or jelly. Never shall I see it more, Till common sense returning, My body to my legs restore, Then I shall cease from mourning. Folly and fashion do prevail To such extremes upon the fair A woman’s only top and tail, The body’s banish’d God knows where!

Fashionable ladies could not have paid much attention, as the waist remained high until the mid-1820s, with only a brief hiatus whilst Napoleon excluded England from trade with Europe. The first ‘Grecian’ gowns were simle shifts of muslin with practically no shape except that given by a ribbon tied beneath the bosom. It was a style most suited to the young and slender, and although it did not carry the political significance held in France, the freedom and comfort of a light gown worn with little underpinning and flat slippers must have been a relief that many women were unwilling to give up.

Wiener Moden, 1816. A long-sleeved evening gown of white gauze with pink satin roses and a striped satin petticoat worn with pink shoes and white gloves.

Gowns were décolleté even for day when the neckline might be ‘V’-shaped or square with a tucker. The round gown had bodice and skirt joined with a seam round the waistline, whereas open gowns were split at the front – as they had been for much of the eighteenth century – allowing an underskirt of contrasting colour or fabric to show.

‘Half Dress’ (Ackermann’s Repository, 1816). Half dress of pink and white striped percale with Mameluke sleeves, knots of green ribbon and white ruchings. After 1810 skirts were more frequently shorter with decorative details around the hem.

The petticoat was a dress worn beneath the robe or open gown as another layer of formal garment rather than underwear. The petticoat provided a convenient extra layer that could be used to give a contrast or depth of colour allowing the outer dress to be gossamer thin. A modern variation appearing at the turn of the century was the tunic dress, extremely popular for its Greco-Roman overtones; it had a tunic often in a contrasting colour bordered in gold, worn asymmetrically over a plain dress.

It could also allow the richer fabric of the outer dress to be tucked out of the way when walking through muddy lanes without the danger of showing an indecent ankle. But even this was not without criticism as Elizabeth Bennet found when she arrived at Netherfield to visit her sister after a three-mile cross-country walk. Miss Bingley couldn’t wait to say: ‘I hope you saw her petticoat, six inches deep in mud, I am absolutely certain; and the gown which had been let down to hide it not doing its office.’ Older dresses were often recycled as petticoats, as Jane Austen mentions in a letter in December 1798.

Trains became a feature of gowns for day and evening wear in 1800 as Oliver Goldsmith notes:

As a lady’s quality or fashion was once determined here by the circumference of her hoop, both are now measured by the length of her tail. Women of moderate fortunes are contented with tails moderately long but ladies of true taste and distinction set no bounds to their ambition in this particular.

‘Evening Dress’ (Ackermann’s Repository, October 1817). Beautiful evening dress with tiers of Vandyked lace and rouleau bound with strings of pearls.

Men were often less enthusiastic, complaining of tripping over them, but many gowns had a method of allowing the train to be pulled up out of the way like those of Catherine and Isabella Thorpe, who ‘pinned up each other’s train for the dance’ when they were dancing at the assembly rooms in Northanger Abbey.

It is impossible to underestimate how important dancing was to the Regency lady; there were so few opportunities to meet that eligible bachelor with ten thousand a year, and so much competition in the flooded marriage market that every ball or assembly had to be approached strategically with the perfect gown as the most important element.

Just as riding costume offered men a freedom of cut that was so desirable that it was translated into ordinary wear, it did the same for women. Providing a more practical yet still fashionable ensemble, the riding habit frequently enjoyed male styling, taking its inspiration from the gentleman’s greatcoat towards the end of the eighteenth century, and sporting military braid at the beginning of the nineteenth. Usually made from woolen, or in summer linen fabrics, it became popular for travelling and more energetic activities. Brides often chose a new riding habit as their going-away outfit. In Emma, Jane Fairfax is wearing hers for a boat trip at Weymouth when she is nearly ‘dashed into the sea’ only to be saved by Mr Dixon who ‘with the greatest presence of mind, caught hold of her habit’.

A Group of Waltzers, 1817. Dancing was a wonderful opportunity for a young lady to display her beauty and grace; it also offered a very rare chance for her to speak to a beau without being overheard by her ever-present chaperone.

The Squire’s Door (after George Morland, c. 1790). A stylish riding habit with wide lapels and caped shoulders is based on a gentleman’s greatcoat. Her hat echoes the new taller masculine styles as worn by the gentleman in the background.

La Belle Assemblée (February 1813). The caption read: ‘A stone coloured habit, trimmed round the body with swansdown, and ornamented entirely across the bosom with a thick row of rich silk braiding to correspond … Large bear or seal skin muff; stone coloured kid gloves, and black kid sandals.’

‘Spencer’ (Ackermann’s Repository, 1817). For an English winter – indeed, many days in an English summer – a muslin gown would have been too cold and the Spencer was readily taken up for warmth, as Jane notes in June 1808: ‘My kerseymere Spencer is quite the comfort of our Evening walks.’

From the late 1790s, for daywear, redingotes, pelisses, and riding habits, sleeves for both men and women were very long, fitted to the wrist and covering the back of the hand to the top of the thumb. For evening ‘full dress’ the short puffed sleeve reigned supreme until 1807 when La Belle Assemblée announced: ‘the long sleeve is very generally introduced in evening dress but is ever composed of the clearest materials; sometimes of lace, patent or spider-net, and embroidered book muslin.’ Even so, the accepted formal short sleeve was so established that in 1814 Jane wrote:

I wear my gauze gown today long sleeves & all; I shall see how they succeed, but as yet I have no reason to suppose long sleeves are allowable. Mrs. Tilson has long sleeves too, & she assured me that they are worn in the evening by many. I was glad to hear this.

She wrote in another letter later the same year from London, ‘long sleeves appear universal, even as Dress.’

Jane Austen’s pelisse, c. 1814. Made in twill weave silk with a repeat design of oak leaves, it would suggest that she was quite tall and slender at approximately 5 feet 7 inches, with a 30–32-inch bust, making her a modern UK size 6 or US size 2.

The Spencer became the most fashionable solution for keeping warm, remaining in style until the second decade of the nineteenth century. It was named after Lord Spencer who when he singed his coat tails whilst warming himself in front of the fire removed the tails and wore the coat without! It translated to women’s wear, coming into fashion in the 1790s as a short fitted jacket only as long as the bodice, usually with long fitted sleeves and high collar. Typically made of woollen cloth, or possibly silkor velvet, it was almost always a strong colour, in contrast to the white skirt of the gown beneath, and had the added advantage of complementing the lines of the gown.

Another development of the late 1790s was the pelisse. Like a coat, it was an over garment that could be added for warmth on cold days, cut with a high waist and skirt to follow the line of the gown it was worn with. It had the potential for glamour as Fanny Price found in Mansfield Park when, during a visit to Portsmouth, judgment was passed on hers – ‘she neither played on the pianoforte nor wore fine pelisses’ – and she was found less than socially desirable.

The pelisse came into its own as gowns narrowed after the turn of the century partly because it complemented the leaner line, and partly because the thin muslin gowns with scant underwear were leaving ladies positively chilled. The pelisse was a welcome outer layer for warmth and being a heavier fabric – velvet or wool in the colder months, and sarsenet or silks in summer – it provided a new scope for decoration.