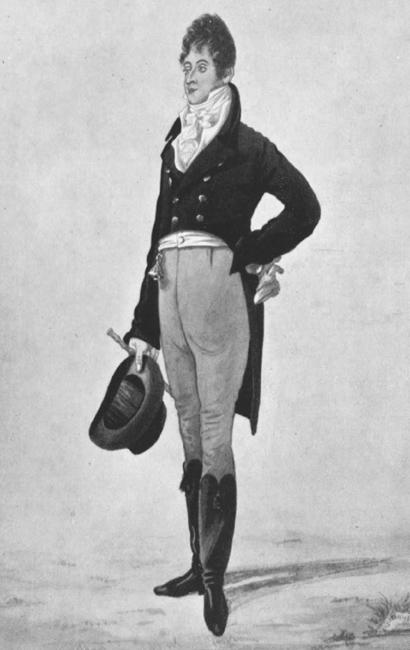

Portrait of George ‘Beau’ Brummell (Robert Dighton, 1805). George Beau Brummell used subtlety to frame his ego with an arrogant insouciance, which was doggedly emulated by his followers – including his ‘fat friend’ the Prince Regent.

JANE MAKES little comment about men’s apparel, but in the understated elegance she writes for Mr Darcy it is easy to see the hallmark of Beau Brummell. It is testament to the power of a prodigious personality that Beau Brummell, through his connection with the Regent, was able to influence such a profound change in dress almost single-handed. The genus of the idea – the English country gentleman’s cut-away riding coat, tight pantaloons, tall boots and tall hat – had been batted back and forth from England to France for years but it was Beau Brummell who made it the only acceptable way for a fashionable gentleman to dress. Under his direction, the style à l’anglaise was drawn away from the discordant statement of the Revolution and into modernity, creating the ensemble that would be the basis of the male wardrobe for the next hundred years.

The Regency gentleman was no stranger to colour: combinations of black, white and sage green; purple, white and yellow; or blue, crimson and canary were all thought to be in good taste even with the addition of accessories in other colours. Beau Brummell encouraged a more subtle palette of a well-tailored dark cloth jacket, plain light waistcoat, tightly fitted light leg wear and freshly laundered starched linen. These hallmarks of sobriety were defined by taste and self-assured style rather than the rich overstated trappings of hereditary status.

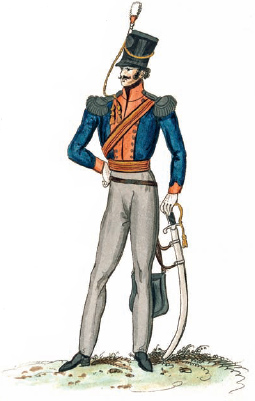

Lord Byron wrote of George Beau Brummell as being the second most important man in Europe after Napoleon – placing himself as a modest third! This cannot have been very pleasing to the poor old Regent who reputedly felt himself a rather disappointing portly second in the fashion stakes, and compensated for his lack of personal glamour by constantly tweaking the details of the uniforms belonging to his regiments. Beau Brummell had been in the Prince of Wales’ Regiment the 10th Hussars from 1794 to 1798, and being part of this most glamorous regiment can only have compounded his already fastidious approach to dress.

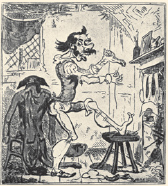

Applying classical principles of line and proportion along with subtle tonal shades, the silhouette was defined by its tailoring. Classical statues showed men tall, lean limbed, broad shouldered and heroic. They also often showed them unclothed, so naturally a trouser to define a strong well-turned leg would be bias cut and skin-tight in a light neutral shade almost the colour of flesh. For those with less than heroic proportions, the art of the tailor sculpted them anew from cloth, padding puny shoulders and arms, puffing out sunken chests and corseting well-fed stomachs. Even a scraggy or twisted leg could be made more ‘poetic’ by judicious padding but, as the cavalry officer who wrote The Whole Art of Dress advised, ‘in which cases a slight degree of stuffing is absolutely requisite, but the greatest care and circumspection should be used.’

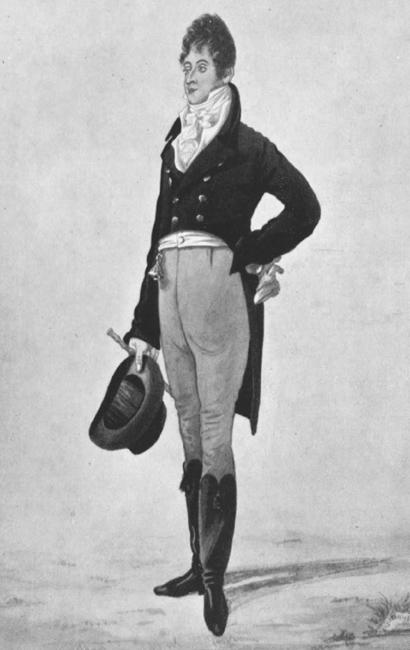

Henry Brougham, 1st Baron Brougham and Vaux (by Sir Thomas Lawrence c. 1810).Although Beau Brummell introduced a subtle palette, it was often worn with a sense of drama, as befitting the young journalist and co-founder of the Edinburgh Review shortly after he was called to the London bar.

Hamburger Journal der Moden und Eleganz, 1802. About Tom Lefroy with whom she had a flirtation, Jane wrote to Cassandra, ‘he has but one fault, which time will, I trust, entirely remove – it is that his morning coat is a great deal too light.’

The dandy was not the decorated fop of the eighteenth century, but exemplary of modern man informed by classicism and the heroic model set by Nelson and Wellington. Cut and fit were everything, creating a codified language for those in the know. Brummell’s credo was, ‘If John Bull turns to look after you, you are not well dressed’. Wealth was whispered in the skill of the tailor, not the precious fabrics, and class was implied by the hauteur given by a correctly tied cravat that held the head high causing movement to be limited and precise. In his biography of Brummell, Captain Jesse recalls:

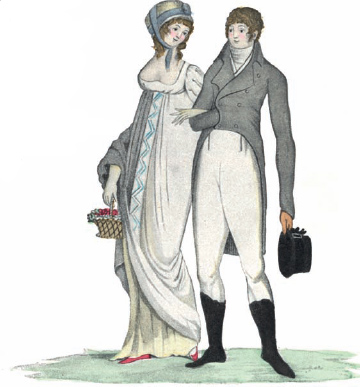

Brummell as a Young Man (engraved by J. Cooke). Tying the perfect cravat could take hours, and many attempts, each starched neckcloth discarded if it did not tie correctly the first time. Captain Jesse saw Brummell’s valet ‘coming downstairs one day with a quantity of tumbled neckcloths under his arm, and being interrogated on the subject, [he] solemnly replied “Oh, they are our failures.”’

The collar which was always fixed to his shirt, was so large that, before being folded down, it completely hid his head and face, and the white neckcloth was at least a foot in height. The first coup d’archet was made with the shirt collar, which he folded down to its proper size; and Brummell then standing before the glass, with his chin poked up to the ceiling, by the gentle and gradual declension of his lower jaw, creased the cravat to reasonable dimensions, the form of each succeeding crease being perfected with the shirt which he had just discarded.

Lieutenant Henry Lygon, 4th Earl of Beauchamp (miniature by John Smart Junior, 1803). Thought to have been painted shortly after he matriculated from Oxford and gained the rank of officer in the 13th and 16th Light Dragoons. The dashing uniforms of the Prussian Hussars were a huge influence on the uniforms designed for the British military, not least the increasingly fancy designs contributed by the Prince Regent.

Brummell’s dress ethos was the first step in social mobility allowing for those like Pen’s father in Thackeray’s Pendennis to slip up a class from moneyed trade to the middle class of minor gentleman. Otherwise social mobility was through the Navy where there were opportunities to gain wealth from the ‘prize money’ divvied up between the crew when an enemy ship was captured, or the Army, where officers were invited to mix with the best families in England and had unprecedented opportunities to make money in foreign lands.

A Gentleman’s Toilet (Lewis Marks, 1800). Women were not the only ones to wear falsies; men resortd to their own artifice, and ‘false curves’ were popular to make a puny leg more ‘poetic’.

With two brothers serving, Jane’s affiliation lay strongly with the Navy, who were rapidly redeeming their seamy reputations through victory and heroism. With the Navy protecting England with an ‘impenetrable wooden wall’, the militia were left to keep order within. Aside from a few locally contained riots there was not too much to do, and the militia quite swiftly earned a reputation for being more interested in drilling and parties than any kind of action.

Where Naval uniforms in trusty blue were generally still cut from a pattern designed in the 1780s, the glamorous bright red uniforms of the militia were up to date, with tightly fitted trousers, short jackets and hessian boots. The Navy needed more than eight hundred crew for each warship and thousands of men were far away at the front line, whereas the men in the militia (like Wickham) were at home partying and using their military splendour to turn young girls’ heads, especially those rather superficial like Lydia Bennet. Older women were not immune, however, as Jane wrote for Mrs Bennet: ‘I remember the time when I liked a red coat myself very well…

Second Dragoons 1812. This soldier’s tall shako hat is attached to his jacket by a lanyard to avoid it being lost in battle and his sabretache hanging behind his knee would be more easily accessible when on horseback. He is wearing grey trousers as part of battledress. Known as ‘overalls’, they probably serve to keep his white pantaloons clean.

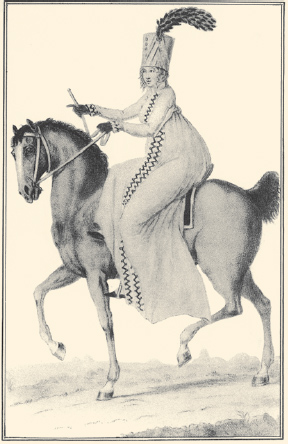

Riding costume (1798) with military inspired shako hat.

I thought Colonel Forster looked very becoming the other night at Sir William’s in his regimentals.’

In The Post-Captain John Davis wrote: ‘Women, like mackerel ... are caught with a red bait ... the blue jacket stands no chance.’ It was not surprising that all the girls – and women – liked a man in uniform because most regiments in fact selected their recruits for their tall slim stature and youthful good looks. Some colonels actually found reason to discharge their veteran officers despite their obvious value in the melee because they wanted to replace them with younger more attractive men to improve the look of their regiment and therefore its prestige. Even so, Jane’s loyalty remained with her brothers and William Price, who was ‘complete in his lieutenant’s uniform, looking and moving all the taller, firmer, and more graceful for it’ in Mansfield Park.

Most found military glamour to be the height of chic; the towering shako hats, the gleaming gold braid, and flashing sword sent a clear message of indomitable strength. Many ladies in support of their officer beaux wore a feminised version of their uniforms with hussar jackets, pelisses, and Spencers with braid and frogging, whilst for civilian gentlemen there was an interchange of fashion from military to civilian dress and back. Pantaloons and Hessians became hugely popular at least partially because they were part of the heroic military image. Pantaloons were officially sanctioned for military campaigns in 1803, but even before that officers wore them at home – ‘very proud of ourselves when at outquarters, we could thus dress, as it looked so like service’.

The Regency ‘Buck’ or ‘Blood’ so beloved of Pierce Egan was the bold, loud contrast to the waspish dandy. To the Buck, dress was only an adjunct to winning, whether racing horses, betting, or cards. They had also adapted the English country gentleman’s look but their colours were brighter, their cut less artful, and their waistcoats were patterned. Their boots were allowed to get dirty and they would never dream of wearing the dress shoes and stirrup pantaloons that dandy Londoners had adopted for half dress.

The new style of male dressing certainly had its detractors – in 1803 the General Evening Post reports of a ‘Brighton Blood’ starting his day by ‘endeavouring to give [himself] a slovenly appearance’. Jane was also less than enamoured: although Tom Bertram in Mansfield Park is something of a Buck his costume remains with the gentlemanly norm, but it is strident and odious John Thorpe in Northanger Abbey whom she characterises as:

…a stout young man, of middling height, who, with a plain face and ungraceful form seemed fearful of being too handsome, unless he wore the dress of a groom, and too much like a gentleman unless he were easy where he ought to be civil, and impudent where he might be allowed to be easy.

Military inspired styles were very popular, like this French Carriage Dress (La Belle Assemblée, March 1818) adorned by military style braid ‘frogging’, the braid made into knots and loops to be used as fastenings.

Gentleman’s Garrick greatcoat. Lady Lyttelton writes of the Barouche Club gentry in a letter in 1810: ‘a set of hopeless young men who think of no earthly thing but how to make themselves like coachmen … have formed themselves into a club, inventing new slang words, adding new capes to their great-coats and learning to suck a quid of tobacco and chew a wisp of straw …’