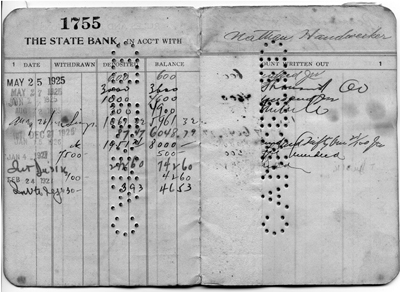

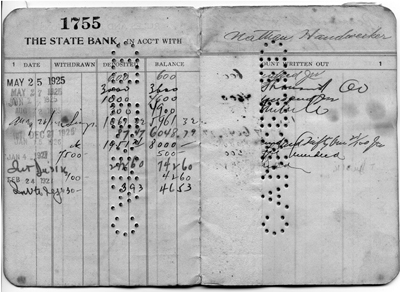

“It was just a single restaurant, but the place was run with procedures that rivaled IBM.” Nathan’s 1925 bank ledger.

BACK IN 1917, the year after Nathan opened the store, Kenneth F. Sutherland Jr. got himself named the district leader of local Brooklyn Democrats. The son of a machine boss from nearby Gravesend, Sutherland gradually rose in the party ranks to wield nearly as much influence as his father. Familiarly addressed as “Senator” after he served a stint as a state congressman, he became Nathan’s longtime political ally.

Sutherland’s other nickname was “Little Corporal,” a nod to both his stature and his Napoleonic tendencies. He enjoyed the kind of power and reach that could make someone a governor of the state. Coney Island had always followed the “big man” model of politics. The crescent of sandy seaside wasteland had been a prize fought after by a lot of competing interests, and the battles had been close and bitter ever since the dawn of the nineteenth century. Land grabs, graft, and backroom deals were the norm.

Twentieth-century bosses couldn’t possibly compete with the corruption of the legendary John Y. McKane, the post–Civil War overlord of Coney Island who once publicly made the forthright claim that “houses of prostitution are a necessity” in any seaside resort. One of McKane’s henchmen was Kenneth F. Sutherland Sr., a.k.a. “the Czar of Coney Island,” who served a stretch in Sing Sing for election fraud. He died in 1910 after being “horribly mangled” in a subway accident.

The son inherited the sins of the father. By the 1930s, Kenny Sutherland Jr. had Coney Island firmly in his grip. Nathan was right there beside him. The immigrant from Habsburg Galicia well understood the big-man style of power. He formed an easy association with Sutherland, becoming, according to one observer, “as close as cousins.” The two of them essentially came up together, the one using successive terms as state assemblyman and senator to cement his power, the other witnessing his business succeed beyond his wildest dreams.

Food was Nathan’s passport to influence. He joined the Coney Island Chamber of Commerce, eventually serving as president. Courtesy of his good friend Max Kamiel, Nathan also became an initiate in the mysteries of Freemasonry. When the political powers of the Sixteenth District flocked together, Nathan always catered the event.

Every year, the political elites of the area went away for a weeklong Catskills retreat. The so-called Monroe Boys (named after Monroe, New York, where they sometimes gathered), also referred to as the “summer group,” included insiders and old-timers: councilmen, the borough president, judges, and congressional representatives and their minions from all over Brooklyn, but especially from Coney Island. Backs were slapped, hands were glad-handed, and backroom deals were hammered out.

“They were all there, the biggest of the big, and they would really let their hair down,” remembered summer group member Pat Auletta, father of writer Ken Auletta and lifelong Coney Island resident (he was one of a series of people to claim the title of “mayor of Coney Island”).

The annual retreat centered around eating, drinking, and playing cards. The big shots were inveterate practical jokers. Disdaining the mundane idea of giving a hot foot, they would ignite a whole fire underneath the bed of a napping fellow Monroe Boy. They once had one of their group, a Brooklyn judge, falsely arrested and put in jail, supposedly for stealing a car.

Every year for the event, Nathan would supply hot dogs, hamburgers, and perhaps a side of beef. He would shuttle back and forth from the store to the Catskills retreat, bringing supplies for the hungry politicos. The obvious success of his business and its geographic centrality in the Coney Island landscape—the store was hard to miss with its huge, busy billboards blaring out above Surf Avenue—established Nathan Handwerker’s local bona fides.

Eventually, courtesy of his achievements and his participation in such insider rituals as the summer group retreat, Nathan took his place as an integral member of the Brooklyn establishment. In contemporary political parlance, he was a job creator. The store had become a major local employer, “the General Motors of Coney Island,” in the words of one insider.

Back when he started out, Nathan had worried about interference from local power brokers for daring to offer a nickel frankfurter. He came to understood that in America as in Europe, good connections made for good business. The Jewish immigrant, a perennial outsider, had arrived at last, if only as a caterer.

His association with Sutherland paid off in concrete ways. With the rise of car culture in America, Nathan’s Famous depended less on foot traffic and more and more on customers who arrived by automobile. Lack of parking was a perpetual concern. Plus there was the pesky problem of a pair of fire hydrants along the curb. They interfered with the vehicles that piled up two or three deep during busy periods.

Might it be possible to have the hydrants moved farther down Surf Avenue? And while you are at it, could the bus stop in front of the store please be placed somewhere else? That would give Nathan’s Famous clear street frontage to work with. An expensive proposition, digging up the water lines and relocating the fireplugs. And people always screamed when their bus stop was displaced. But Kenny Sutherland got it all done for his good friend Nathan.

Favors flowed the other way, too. Pat Auletta said that Sutherland was definitely an authority figure for Nathan. “If Kenny Sutherland told him to jump off the Empire State Building, I think Nathan would have done just that,” Auletta recalled.

Sutherland might have been at the apex of the Coney Island food chain, but he still couldn’t be everywhere at once. He relied on the local constabulary as the physical expression of his power. True to form, the big man granted Nathan’s Famous the incredible benefit of having its very own cops.

Veteran manager Jay Cohen: “Nathan’s being located as it was, and as many people that visited the place in the summer months, it required a lot of police to cover the area for crime, for pickpockets, and things of that sort.”

Friendly police officers were valuable for what they could do—crime suppression, traffic control, breaking up fights—but also for what they would not do—write parking tickets.

“If a car was double-parked, the driver ran across the street and picked up three hot dogs, a bag of french fries, and a soda,” Cohen said. “He’d go back to his car and eat. As management, we did not want him to be harassed by the police writing him up with summonses.”

Courtesy of Nathan’s good standing with the powers that be, two police officers were assigned to the sidewalks in front of the store at all times. Each cop worked an eight-hour shift, and there were three shifts per day. Joe Handwerker usually handled the greasing of palms, allowing Nathan to stay out of the fray.

“At the end of the week, every one of those men—which makes six tours, because there’s two men each—would get two dollars per day as their tip to make sure that they stayed on the premises,” Jay Cohen said. “If the management had trouble with a rowdy customer, a policeman would step in. Of course, he would take your side, because after all, in his own way, he was on your payroll.”

The baksheesh didn’t stop with the beat cops. The mounted police would also receive what Cohen referred to as “our two-dollar-a-day retainer.” At the end of every season, the lieutenants and captains at the local precinct house also got their due. Emissaries from the store would visit and introduce themselves. Envelopes changed hands. Whenever a new police chief took office, Joe Handwerker made a pilgrimage with a paper bag full of money.

“It was a known fact that Nathan’s was good people to the police department,” Cohen said.

Good in more ways than one. Eventually, Nathan actually created a second break room at the store, next to the employees’ break room but reserved for the exclusive use of the police. The employees’ dining room also saw a lot of blue uniforms.

“They knew that they could come in the back door and eat,” Cohen said. “There was many a day when the employees’ dining room had twenty to thirty policemen eating there. Eighty percent of them never paid. That’s the way Nathan ran the business.”

At times, the cops caused problems instead of heading them off. “At four o’clock in the morning, we had to stop selling beer,” recalled Hy Brown. “We had to turn off the spigots on a Friday night at four and on Saturday night at three. We had a lot of drunken cops there, all off duty.”

Brown remembered one cop practically assaulting him during an early-morning confrontation. “He took a scissors and cut off my tie. He wanted beer, but we had turned off the air inside, so we couldn’t draw beer outside.”

The demanding cop took out his service pistol and laid it atop the counter. What could Hy Brown do? “I gave him beer.”

Arguments and fistfights, yes. But because of the highly visible presence of the police on the block, the store was never robbed. Except once.

Nathan had gotten his hands on a $1,000 bill that someone came to him to cash. He knew the holder of the bill, a local resident, and the holder knew that Nathan’s Famous was an all-cash business. The bank wouldn’t take such a large denomination, so Nathan was the next best bet.

A circulating thousand-dollar bill was a very rare thing. To collectors, they were worth more than face value. Their official use would soon be suspended, since electronic banking transfers were becoming the norm, and such big bills were being used primarily by organized crime.

The particular bill in question was a Federal Reserve Note from a 1934 issue that featured a portrait of President Grover Cleveland. Nathan decided to hold on to his prize. He had it framed and posted it behind the french fry station, where the store had various signs of all sorts on the wall.

“$1,000—we will present this bill to anyone who can prove that we don’t use pure Mazola cooking oil for our fries.” Placed above bubbling vats of hot oil, the sign was visible but not reachable by the public.

At 3:00 A.M. on a night in 1939, a trio of thieves decided to claim the bill without proving anything at all, yea or nay, about the store’s use of pure corn oil.

“Three guys started an argument,” recalled Nathan’s son Murray, a teenager at the time. “One of them drew the attention of the workers. The other two jumped over the counter and ripped the sign off the wall. They had a car waiting for them. The three ran out to their car, and off they went.”

A thousand dollars, gone in a puff of getaway car exhaust.

Except …

Nathan notified police of the theft. Authorities caught the IQ-challenged culprits in New Jersey when they tried to pass the bill. Collected along with it was the sign from the french fry station’s back wall. To everyone’s surprise except Nathan’s, the bill proved to be counterfeit.

Before he would agree to cash it, Nathan of course had gone to the bank and checked out the validity of the bill himself.

“They told him, ‘No, it’s a counterfeit.’ They wanted to take it away from him, they wanted to condemn it and withdraw it from the market,” Murray recalled. “But they knew he wasn’t going to pass it off to someone else, so they gave him the bill.”

Nathan had told no one about the counterfeit. He did not pony up the cash for the holder who had offered it to him but simply posted the bill as if it were real. A couple of lessons can be gleaned here. One is that Nathan always held his cards extremely close to his chest. Another is that he had the kind of pull in the neighborhood that a bank would allow him to keep a thousand-dollar bill that by law should have been confiscated and destroyed.

Reality is like sculpting clay in a PR agent’s hands. Perhaps Murray’s version of the story was shaped by publicity ace Morty Matz. Jack Dreitzer always claimed that he was the one who found the fake $1,000 bill, discarded on a sidewalk in Coney Island. “I turned it over and it was an ad for a French brassiere company,” Dreitzer said.

Mazola continued as the store’s brand of choice. Around that time, Nathan’s Famous, the number-one consumer of cooking oil in the New York metropolitan area, developed a novel delivery system for its prized ingredient. Nathan installed a five-thousand-gallon tank atop the store. Originally, it contained simple sugar syrup that was delivered via copper pipes to the drink vats. Converted to a tank for corn oil, it was connected to a system of gravity-fed tubing that distributed the precious liquid to the voracious deep fryers down below.

As much as the frankfurter was the star of Nathan’s Famous, the potatoes were celebrated also. Deep-fried to a golden brown, they were sold in small cellophane bags, the store’s logo printed on the side. A serving usually came with small, extra-crispy leftover pieces that were, to some, the best part of the meal.

The production process of the crinkle-cut fries rivaled the complicated ballet of frankfurters on the grill. The crispy potatoes were so popular that it took ten fryolators to keep up with demand. (Two smaller fryolators were reserved for other menu items.) Each one of the deep-frying appliances was drained and filtered in the early hours of the morning, tended by a four-man cleanup and rotation crew trained to keep the oil pristine.

“We rotated the oil from left to right as we filled the frylators, and we filtered them at night,” explained Hy Brown. “We used the same procedure, and we started over fresh with the fryolators on the left. That was the secret of the crispy, crunchy potatoes that we had.”

Filter devices cleaned impurities from the cooking oil. Oil from the first fryolator was filtered and transferred to the second, the second to the third, and so on. After the used liquid had been cycled through all ten cookers, the crew transferred it to huge barrels that would later be picked up by waste oil companies.

The fresh potatoes went through a two-step frying process. They were peeled, cut, and cooked at 325 degrees until soft, all processes that occurred in the back kitchen. Workers brought the once-cooked fries to the counter in “wires,” as the large, round metal frying baskets were called. The temperature in the front fryolators was held at 375 degrees, and the fries were finished off there. Whenever the oil started to “cream up”—display a frothy surface—that meant it was dead and could no longer be used.

“Once a fryolator got creamy, it was no good anymore because it would soak the product with oil,” said Brown. “It had to be pretty clear oil for us to cook with it.”

Tanker trucks filled with corn oil pulled up in the alley beside the store twice a week, pumping their contents up to the huge reservoir on the roof. The big Mazola tank would be joined later by the celebrated hot dog clock—with a huge, six-foot-wide dial that sported a pair of wieners for hands—as high-visibility beacons for Nathan’s Famous of that period.

* * *

Nathan’s semiofficial police force patrolled the sidewalks on the block, and Nathan made certain that other members of New York’s Finest felt welcome inside, too. But there was another layer of regulation that kept the business on track. In-house policing proved every bit as essential to success as beat cops and friendships with Coney Island’s power elite.

Business and management practices that Nathan put in place addressed problems of employee theft, yes, but also issues of inventory, production, and sales. Homegrown yet sophisticated, organic yet rigorous, a system gradually came to control all aspects of cooking, serving, supplying, and managing the menu items for which customers eagerly lined up.

When Nathan started his company, his approach to record keeping was crude in the extreme. He remained functionally illiterate. In the course of constantly working with sums of money, however, his facility with numbers gradually developed. Early workers recall him scribbling business records on a back wall of the store’s kitchen, always using a stubby pencil. At the end of the year, he would paint over the numbers and start over, keeping a fresh set of records for the new year. The accounting geniuses at a top firm like PricewaterhouseCoopers might not approve, but it worked for Nathan.

At least at first. As sales volume swelled, Nathan’s Famous was on its way to becoming the busiest restaurant in America. The task of managing all aspects of the business became more difficult. Nathan struggled fiercely to keep up. All the rules he instituted flowed directly from his no-nonsense personality. The store became a mirror of the man. His personal obsessions about cleanliness, quality, and service played out in the day-to-day functioning of the store.

“It was just a single restaurant,” said Charles Schneck, “but the place was run with procedures that rivaled IBM.”

Prominent among those procedures was the Count.

“Everything at Nathan’s was counted,” said former Nathan’s manager Sidney Handwerker. “The frankfurters, the rolls, the french fry bags, everything.” Nathan knew to the dog the number his supplier delivered. He recorded how many he had left at the end of the day. He compared the tally with the amount in the till.

“We used to count frankfurters every day,” recalled Hy Brown. “We knew how many frankfurters we started the day with. We knew how many frankfurters we finished with. Any frankfurters that were broken were put in a separate box. Any frankfurters that were given out free—for employees to eat, or the police, or anybody else who was involved with free frankfurters—we had to put a chip in the register to account for it. The next day when the tallies were finished, they were always pretty close to the amount of money we took in for frankfurters.”

As a method of inventory control, it was pretty basic. But it worked because Nathan had an iron hand. His illiteracy took nothing away from his business acumen.

Former Nathan’s Famous accountant Aaron Eliach recalled showing Nathan a financial statement he had prepared. “I was very proud of myself,” he said, believing he had done excellent work.

Nathan examined the spreadsheet. “You’re $10,000 off in the inventory.”

“How would he know that?” Eliach remembered asking himself. “I didn’t think he knew anything about accounting. But I went through my numbers, and sure enough, he was right.”

Eliach realized that his client basically kept track of the store’s whole business in his head. “Whenever I discussed numbers with him, he knew exactly what I was talking about. He knew everything that was happening. I mean, the inventory wasn’t a small inventory. Ten thousand dollars wasn’t a major part of it, because we had inventory in cold storage and in warehouses. This was just numbers, so $10,000 wasn’t a material amount. How he knew it, I will never figure it out.”

“He felt nothing should interfere with business,” said Hy Brown. “Business was business. He could be the kindest, nicest guy away from the store, but in the store, he didn’t want anybody to think that he was letting down his guard.”

There was another aspect of the Count, just as vital but more troublesome. As owners of other cash businesses know, and all drug dealers come to learn, handling the money can be a much bigger headache than inventory. Banks would not take loose change. Every penny, nickel, dime, and quarter had to be packed into paper sleeves.

The money taken in at the store was in a very literal sense filthy lucre. Coins and bills both were slimed with grease, salt, sand, and sweat. The currency was often crumpled.

With paper money, the job was to count out a hundred one-dollar bills and secure them with a currency wrapper. “You had to take the greasy bills out of a box,” Nathan’s nephew Sidney Handwerker recalled. “To try to flatten them, we used to sit on them.”

Sidney remembered an incident where one of the bills he was sitting on stuck to his behind and threw off his count. “I wrapped up the hundred, and then the next one I put underneath my leg had 101 bills in it,” he said.

Nathan double-checked the kid’s work and saw that the count was off. “Go back on the sandwich station,” Nathan commanded. “You can’t count anymore.” All because a dollar bill had stuck to the bottom of young Sidney’s pants.

Eventually, the money counting operations were transferred to a small room at the back of the store, located beneath the stairs to the second floor. It was what passed for a vault on the premises, where the proceeds from the day’s business wound up. The door was made of metal for security purposes.

Rolling the coins, in particular, was tedious work. Count, roll, count, roll, for hours on end. Nathan’s oldest son, Murray, was often placed on counting duty. “In those days before the machines, you counted with two fingers,” he said. “You spread out the coins—twenty, forty, sixty, eighty. Ten dollars of quarters or nickels. It all had to be packed.”

Tallying the avalanche of coins from the weekend took all of Monday. At every step along the way, there were opportunities for employees to skim. One cleaning person was caught pocketing the coins he salvaged when he took up the store’s floorboards for a steam wash.

How to handle the immense amount of cash bedeviled Nathan for years. The old method of cigar boxes placed beneath the counter was replaced by a fancier system that used suction to vacuum paper currency away from where it was collected, transferring it to central collection boxes. But coin counting remained a thorn in the side of the business. It would not be fully mechanized until the postwar years—and even then, the modernizing process would cause friction between Nathan and his sons.