CHAPTER 16 MASSAGE AND TOUCH THERAPIES

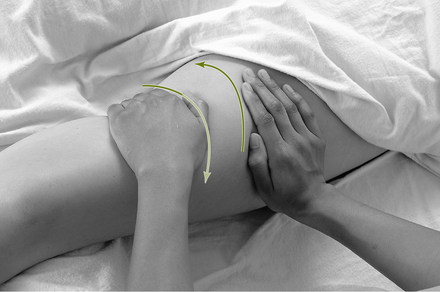

Manipulation as a therapeutic practice has existed for thousands of years. Although the date of origin of the earliest forms of manipulative therapy is unknown, it has been recorded that Hippocrates was skilled in the use of manipulation and taught it in his school of medicine, more than 2000 years ago. In China the history of manual therapy (tui na) predates the development of the technology necessary to produce the needles used for acupuncture, 3000 to 5000 years ago (Figure 16-1).

Figure 16-1 A patient receiving manipulation of the shoulder. Joint manipulation has always been an important feature of Chinese medical treatment.

(Courtesy The Wellcome Trustees, London.)

All the world’s cultures can demonstrate the use of manipulation as a form of therapy. However, much of this information has been passed on as an oral rather than a written tradition, so documentation is difficult or impossible to obtain in many cases. Consequently, the types of manipulative therapy presented here are those for which information is readily available. Although this chapter describes the basic principles and theories of many well-known modalities, it is not totally inclusive of all that exist, nor does it include an extensive discussion of those that are mentioned.

THE BODY’S MATRIX—FASCIA

Whether the modality targets the osseous, muscular, visceral, or even acupuncture structures, it affects, in one way or another, a common integral component—fascia, the colloidal matrix of the body. Fascia comprises one integrated and totally connected network, from the soles of the feet to the attachments on the inner aspects of the skull, and divides the body by diaphragms, septa, and sheaths. However, fascia is so much more than just a background element with an obvious supporting role. It is a ubiquitous, tenacious, living tissue that is deeply involved in almost all of the body’s fundamental processes, including its structure, function, and metabolism.

When any part of the fascial network becomes distorted, resultant and compensating adaptive stresses can be imposed elsewhere on the structures that it divides, envelopes, enmeshes, and supports, and with which it connects. The consequences of a structural cascade are not limited to the structural elements of muscle, tendon, ligament, bone, and disk. Pressure can also be imposed on the neural, blood, and lymph components, which course alongside and through them, and on the visceral organs and glands. Varying degrees of fascial entrapment of neural structures can, in turn, produce a wide range of symptoms and dysfunctions, such as by triggering the neural receptors within the fascia that report to the central nervous system (CNS) as part of any adaptation process. The sources of such signaling might include the pacinian corpuscles, which inform the CNS about the rate of acceleration of movement taking place in the area; the highly specialized, sensitive mechanoreceptors and proprioceptive reporting stations contained in the tendons and ligaments; or the hormones excreted by the glands, which serve as the chemical messengers of metabolism.

Massage and other manual techniques can be used to manipulate the connective tissues, affecting the fascia by altering its ground substance, elongating shortened tissues, and improving the biochemical environment of the cells. A diverse array of massage techniques and systems of application can offer a variety of affects on isolated tissues, overall structural integrity, and general well-being of the individual.

MASSAGE APPLICATION

As with other manipulative forms of therapy, the use of massage predates written history (Figure 16-2). The Greek physician Aesculapius, credited as the inventor of the art of gymnastics (Nissen 1889), became perhaps the first practitioner of the “one cause, one cure” approach when he abandoned the other forms of contemporary medical treatment in favor of massage to restore the free movement of body fluids and return the patient to a state of health. During the Renaissance the physician Ambroise Paré, author of a widely used surgery text, espoused the application of massage and manipulation and was reportedly the first to use the term subluxation. In 1813, Pehr Henrik Ling, a gymnastics instructor, founded the Royal Gymnastic Central Institute, where his theory of massage as passive gymnastics was developed. This work was the genesis of what is now referred to as “Swedish massage,” and Ling is now considered by many to be the father of massage.

Johann Georg Metzger, a Dutch physician and student of Ling, developed a basic classification of massage techniques. Although Metzger’s work was never published, his students von Mosengeil and Helleday wrote and published descriptions of the techniques. In the late nineteenth century the prominent French physician Marie Marcellin Lucas-Champonnière advocated the use of massage therapy in the treatment of fractures, arguing the case for consideration of soft tissue union in the healing process. His students, the English physicians William Bennett and Robert Jones, effectively brought massage to England. Bennett incorporated the use of massage at St. George’s Hospital in London around 1899, and Jones used massage therapy at the Southern Hospital in Liverpool. Jones taught both James Mennell, author of the text Physical Treatment by Movement, Manipulation, and Massage (1917) and a tireless advocate of massage, and Mary McMillan, who was very influential in the introduction and promotion of massage in the United States.

There are many others who contributed both to the development of massage techniques and to documentation of massage through research and writing. Early in the twentieth century, several made significant and long-lasting contributions:

Development of Essential Theories of Massage

As awareness of this form of treatment grew, so did the science of physiology, and the two entities became intertwined with the growth of the scientific basis of medicine. Some authors attribute the development of the physical therapy profession as being an outgrowth of massage. Many other forms of so-called bodywork, an assortment of which are discussed in this chapter, are also outgrowths of massage and its various techniques and styles.

One essential theory of massage therapy is based on the principle that the tissues of the body will function at optimal levels when arterial supply and venous and lymphatic drainage are unimpeded (“rule of the artery”). When this flow becomes unbalanced for any reason, muscle tightness and changes in the nearby skin and fascia will ensue, which may result in pain. The basic techniques of massage are designed to reestablish proper fluid dynamics and are directed at the skin, muscles, and fascia, although nerve pathways occasionally are included. In general, articulations are not directly addressed in this form of therapy, although they certainly may be affected by the applied techniques.

Obvious contraindications to massage or areas to avoid during the application of massage include skin infections or melanoma, bleeding (especially within 48 hours of a traumatic event causing bleeding into tissues), acute inflammation (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, appendicitis), thrombophlebitis, atherosclerosis, varicose veins, and immunocompromised state (to avoid transmission of infection from massage practitioner to patient). In addition, a number of endangerment sites require that extra caution be exercised, such as the region of the carotid artery, supraclavicular fossa, posterior knee, femoral triangle, and abdominal cavity. Specific training may also be required, such as for intraoral applications or for work with lymphedema and cancer patients.

The techniques of massage are generally applied in the direction of the heart to stimulate increased venous and lymphatic drainage from the involved tissues. Muscles are addressed in groups, with one group being treated before advancing to the next. Different combinations of techniques are used depending on the objectives of treatment. Treatment typically begins with more gentle, superficial techniques before progressing to deeper, more aggressive applications. Massage is usually performed with a powder, oil, or other type of lubricant applied to the skin of the patient (or client), who lies prone, supine, or laterally on a table, or who may be seated in a massage chair. Verbal communication between the practitioner and patient is important, because the practitioner will use the cues given by the patient as a guide during the treatment.

The visceral effects of massage include general vasoactivity in somatic tissues as regulated by the autonomic nervous system. Also, effects on blood pressure and/or heart rate (usually decreases in both) can be observed as the person relaxes during the treatment.

Massage Techniques

There are five basic techniques of massage, and all are of the passive variety (i.e., the practitioner does the work). These techniques are effleurage, pétrissage, friction, tapotement, and vibration. There are numerous variations of these basic techniques, which may create different outcomes within the tissue. For instance, effleurage applied at a moderate pace with lubrication increases blood flow and lymphatic drainage. However, effleurage applied with almost no lubrication at a very slow pace produces a shearing force on the tissue that focuses more on changing the ground substance of the fascia. These variations in application provide a vast array of styles, methods, and versions of massage, each with its own foundational platform, despite their common roots in the basic techniques.

Figure 16-3 Effleurage can be applied with thumbs, fingers, palms, or forearm (as shown here).

(Modified from Salvo S: Massage therapy: principles and practice, ed 3, St. Louis, 2007, Saunders.)

Figure 16-4 Friction applied to paraspinal muscles.

(Modified from Salvo S: Massage therapy: principles and practice, ed 3, St. Louis, 2007, Saunders.)

In addition, forces may be applied to the tissue that alter its length, mobility, and density. For instance, a shear force can be applied to a superficial muscle layer to slide it laterally across the underlying muscle and disengage it from a deeper layer, which results in more mobility between the two (Figure 16-5). Stretching a muscle’s fibers can elongate the muscle and result in decompression of the associated joint(s). Elongation of a fascial plane might alter postural alignment and result in improved biomechanics of the region or of the structure body as a whole.

Variations in Application of Techniques

As mentioned previously, variations of these basic techniques produce different outcomes within the tissue. As a result, a multitude of methods, versions, and styles of massage have emerged, with many having broad perspectives regarding application. Although some of the concepts discussed later in the synopsis of various types of massage may seem foreign to the reader, it is worth remembering that many of these applications are centuries, if not millennia, old, far exceeding the experience in the practice of modern medicine. In particular, the Eastern theoretical platforms may contain concepts that do not appear to relate to Western understanding, especially those involving energy, meridians, and mysterious acupuncture points. However, with open and curious minds, even those most academically rooted in Western philosophy can find evidence to support the Eastern principles. The following discussion (after Chaitow and DeLany 2008) provides one example of how Eastern ideas can fit easily into a Western model when research provides physiological support.

Many experts believe that trigger points (see neuromuscular therapy discussion) and acupuncture points are the same phenomenon (Kawakita et al, 2002; Melzack et al, 1977; Plummer, 1980). When traditional and ah shi acupuncture points are both included, approximately 80% of common trigger point sites have been claimed to lie precisely where traditional acupuncture points are situated on meridian maps. (Wall and Melzack, 1990). Some (Birch, 2003; Hong, 2000) find the percentage to be flawed, particularly when the trigger points are correlated with acupuncture points that are seen to be “fixed” anatomically, as on myofascial meridian maps. However, they agree that so-called acupuncture points may well represent the same phenomenon as trigger points. Ah shi points do not appear on the classical acupuncture meridian maps, but refer to “spontaneously tender” points that, when pressed, create a response in the patient of, “Oh yes!” (ah shi). In Chinese medicine ah shi points are treated as “honorary acupuncture points” and, when tender or painful, are addressed in the same way as regular acupuncture points (see Chapter 27). This would seem to make them, in all but name, identical to trigger points.

It is clearly important therefore, in attempting to understand trigger points more fully, to pay attention to current research into acupuncture points and connective tissue in general. Ongoing research at the University of Vermont, led by Dr. Helene Langevin, has produced remarkable new information regarding the function of fascia/connective tissue as well as its relationship to the location of acupuncture points and energy meridians (Langevin et al, 2001, 2002, 2004, 2005).

Langevin and colleagues present evidence that links the network of acupuncture points and meridians to a network formed by interstitial connective tissue. Using a unique dissection and charting method for location of connective tissue (fascial) planes, acupuncture points and acupuncture meridians of the arm, they note that overall, more than 80% of acupuncture points and 50% of meridian intersections of the arm appeared to coincide with intermuscular or intramuscular connective tissue planes (Langevin et al, 2002).

Langevin’s research further shows microscopic evidence that when an acupuncture needle is inserted and rotated (as is classically performed in acupuncture treatment), a “whorl” of connective tissue forms around the needle, thereby creating a tight mechanical coupling between the tissue and the needle. The tension placed on the connective tissue as a result of further movements of the needle delivers a mechanical stimulus at the cellular level. They note that changes in the extracellular matrix may, in turn, influence the various cell populations sharing this connective tissue matrix (e.g., fibroblasts, sensory afferents, immune and vascular cells).

Chaitow and DeLany (2008) summarize the key elements of Langevin’s research as follows:

As more researchers seek to understand the overlap of Eastern and Western platforms, the parallels between the two will likely become more evident. In addition, as one can readily see, there are many “less than ideal” outcomes in modern patient care. It is important to consider that the following methods often offer significant relief to the suffering patient, with virtually no risk for potential injury or death. In an environment in which the costs of health care are out of control and the potential for medical error is seriously increasing, consideration for their use would seem to be practical, prudent, and economical.

The various massage styles and methods included in the following discussion are arranged alphabetically, with no indication as to which is most useful or more popular. The method’s inclusion in the list and the length of any particular discussion only indicates the authors’ familiarity and/or fascination with the method and implies nothing regarding its success, value, or appropriate use. Similarly, exclusion from this list simply indicates the restrictions applied in writing a brief chapter for this book, one that only begins to touch on the value, range, and scope of manual techniques. All appropriate touch therapies have intrinsic value, the degree of which is likely to be dependant on the practitioner’s degree of mastery.

ACUPRESSURE AND JIN SHIN DO

Acupressure is the application of the fingers to acupuncture points on the body, or “acupuncture without needles.” It is based on the meridian or channel system, which permeates Asian medical arts and philosophy. According to this system, there are 12 major channels through which the body’s energy, or qi (or chi), flows. Although most of the channels are named for specific organs, they do not necessarily correspond to the anatomical body part, but rather are more functional in nature. Interruptions in the flow of qi (prana, ki, vital energy, as described in other cultures) cause functional aberrations associated with that particular channel. These interruptions can be released by specific application of needles or fingers.

Jin shin do, or the “way of the compassionate spirit,” was developed by psychotherapist Iona Teeguarden (1978). It is a form of acupressure in which the fingers are used to apply deep pressure to hypersensitive acupuncture points. Jin shin do represents a synthesis of Taoist philosophy, psychology, breathing, and acupressure techniques. In accordance with this philosophy, the body is linked to the mind and spirit, and tender points found in the body can represent expressions of emotional trauma or locked memories (i.e., the somatoemotional component) (Figure 16-6).

Figure 16-6 Traditional Asian medicine focuses on the assessment and balancing of energetic systems.

(Modified from Salvo S: Massage therapy: principles and practice, ed 3, St. Louis, 2007, Saunders.)

The theory of jin shin do states that various stimuli cause energy to accumulate in acupuncture points. Repeated stress in turn causes a layering of tension at the point, known as armoring. The most painful point is termed the local point as a frame of reference. Other related tender points are referred to as distal points. Deep pressure applied to the point ultimately causes a release, and the tension dissipates. The overall effect is to reestablish flow in the channel and balance body energy. The context of the jin shin do treatment is as much psychological as physical and reiterates the importance of the body-mind-spirit philosophy of this treatment form.

During the treatment session the practitioner identifies a local point and asks permission nonverbally to treat it. A finger is placed on the local point while another finger is applied to a distal point. Gradually increasing pressure is applied to the local point. After 1 or 2 minutes the practitioner feels the muscle relaxing, followed by a pulsation (practitioners of craniosacral therapy refer to this phenomenon as the “therapeutic pulse”). When the pulsing stops, the patient usually reports a decreased sensitivity at the point, indicating a successful treatment. Myofascial releases are sometimes accompanied by emotional releases as painful memories are brought to consciousness.

AYURVEDIC MANIPULATION

In Sanskrit, Ayurveda means “the study or science of life.” As a healing art, Ayurveda is one of the world’s oldest and, like the Indian culture, probably predates traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). As with TCM, Ayurveda has many concepts and components, as discussed elsewhere in this book. However, several principles pervade Ayurveda (as they do in TCM) and apply to the manual component of Ayurvedic treatment.

Both Ayurvedic and Chinese theory present five basic elements. In contrast to those of Chinese theory (fire, water, earth, wood, metal), however, Ayurveda defines space (ether), air, fire, water, and earth as the five basic elements. These elements flow through the body with one or more predominating in certain areas, corresponding to specific organs, emotions, and other categories. Prana, or the life force (qi, ki), also flows through the body, permeating the organs and tissues, and is especially concentrated at various points along the midline of the body, known as chakras.

The unity and balance of body, mind, and spirit have deep cultural roots in Ayurveda. Body structure and a person’s actions, feelings, and beliefs all reflect his or her constitution. The human constitution is based on the relative proportions and strengths of these three constituents (mind, body, spirit) and the five elements. Three basic types of constitutions (doshas) are recognized, which are based on different combinations of the five elements. The first, vata, is a combination of air and space and is reflected in kinetic energy. The second, pitta, combines fire and water and reflects a balance between kinetic and potential (stored) energy, which is expressed in the third constitution, kapha, a combination of earth and water.

The manipulative treatment developed within the Ayurvedic tradition offers three types of touch. Tamasic is strong and solid, firmly rooted in the earth (and might be well suited for a kapha constitution). The application is fast, and time is needed for the mind and spirit to “catch up.” Tamasic might correspond to high-velocity low-amplitude technique (osteopathy, chiropractic), tapotement (massage), or rubbing and thumb rocking (TCM). The second type of touch, rajasic, is slower and is used to expand and integrate initial manual explorations and findings. It is more in resonance with the mind and spirit. As mentioned earlier, greater depth can be achieved with less tissue resistance due to the makeup of the body fascia. Effleurage (massage) and myofascial release (osteopathy) might correspond to this type of touch, which in turn might be more suited to a pitta constitution. The vata constitution might benefit from the third type of touch, satvic, in which the application is very slow and gentle and can follow the intention of the mind and spirit. This might correspond to cranial osteopathy, sacro-occipital technique (chiropractic), counterstrain (osteopathy), Trager work, the Feldenkrais method, or healing or therapeutic touch.

In a massage-oriented treatment, different oils are used as lubricants according to the constitution of the individual and the problem to be treated. The patient is prone or supine, lying on either side, or sitting up, with the positions arranged in a specific sequence. Strokes are applied either toward or away from the heart, also in a specific sequence. Another technique, which is rarely encountered, uses the feet to perform the manipulation. The practitioner stands above the patient, who is lying prone on a reed mat, and applies the technique with the feet. Oils again are used as lubricants, and to maintain balance, the practitioner holds onto a cord strung lengthwise above the patient. The strokes go from the sacrum up the spine and out to the fingers, then back down to the feet. One side is done, then the other. The patient then lies supine, and the process is repeated.

Techniques can be direct or indirect relative to motion barriers. They can also be active or passive. Both the patient and the practitioner act as partners during treatment, exploring tissue and motion in an attempt to unlock the body and restore the unimpeded flow of prana and constitutional balance. Visualization, nonverbal communication, and mind intent are elements of treatment, regardless of the technique employed.

ENERGY WORK

Energy work refers to the techniques that have developed either as part of ancient traditions (e.g., qigong, Qi Gong) or as recently “discovered” methods in which the practitioner manipulates the bioenergy of the patient. The theory of bioenergy basically states that a life force, or vital energy, permeates the entire universe. This energy flows through all living things in distinct patterns. These patterns of flow are reflected in the meridian system (where qi, or chi, is the name of the life force) originally conceived by the Chinese and in the chakra system of Hindu tradition (where the word prana is used to indicate this force). Various forms of exercise have been developed for the cultivation of bioenergy, including yoga, internal qigong, and t’ai chi.

Three basic concepts are important in understanding energy work: intent, cooperation, and the tripartite nature of the human. Intent is important in that the practitioner projects his or her mind intent to heal into the patient. For this reason, that intent must go one step further than the “do no harm” doctrine of Western therapeutics to an attitude of love and concern. Intent also assumes a high level of visualization. Cooperation implies the partnership between the practitioner and patient as participants in the healing process, with neither being exclusively active or passive. The tripartite concept refers to the acceptance of three parts of the human: body, mind, and spirit. This concept is envisioned in the much older Asian cultures as going beyond religion, whereas Western cultures rely on belief systems driven by faith. In addition, the “scientific,” reductionist approach of conventional Western medicine is rather dismissive of spiritual aspects and has only recently acknowledged the mind-body connection. Although there are many systems of energy work, four are included here, two rooted in Eastern teachings and two developed in Western application.

The Chinese term qigong (or qi gong, Qigong, Qi Gong) refers to the manipulation of bioenergy and loosely translated means “qi work.” Qigong can be internal, in which an individual can strengthen and balance the flow of qi within the self, or external, in which a trained practitioner can project his or her qi into a patient to induce a therapeutic effect.

Although the vast majority of the vital energy of an organism is contained within the body, some of it radiates off the skin, the “aura,” which has been visualized using Kirlian photography. The qigong practitioner is able to palpate the meridian system through this aura, locate points of blockage, and free these blockages by projecting his or her qi into the patient, using intent and visualization. As in Trager work, the Feldenkrais method, and yoga, specific “external qigong” exercises have been developed that, when performed by an individual, serve to cultivate qi within the self. Qigong is also a natural result of long-term “internal” martial arts training, in which practitioners are capable of seemingly superhuman feats of strength and balance.

Reiki (literally “universal energy”) is a method that most likely originated from qigong as practiced by the Chinese Taoists and Buddhists. It probably disappeared from practice in Japan at some point, only to be “rediscovered” by Dr. Mikao Usui in the mid-nineteenth century. Usui was interested in determining the nature of spiritually oriented healing power, as expressed through such individuals as Jesus Christ and the Gautama Buddha. After much study, including a doctorate from the University of Chicago, he began an extended period of fasting and meditation. At the end of this period, he reportedly received a vision and the ability to channel “reiki” through his body to effect healing in others. From that point, he continued healing, eventually training others in his method. Usui handed the title of Grand Master to Dr. Hiyashi Chugiro, who in turn passed it to Hawayo Takata, a Hawaiian woman of Japanese descent. In this way, reiki was exported from Japan to the West.

For practitioners, reiki must be “received” from a master or teacher. Only then is an individual able to effect healing. There are three degrees of reiki training. The first-degree practitioner is capable of giving a basic treatment with the hands on the patient, or about 1 inch away from the skin if touching is not possible. The second-degree practitioner can effect healing with the hands removed from the body, and treatments can be given at a faster rate. The third-degree practitioner is referred to as a “master” and is qualified to teach reiki.

The objective of reiki treatment is to restore internal harmony to the body and to release any blockages, which may be physical or emotional. The five principles of reiki are as follows:

During a reiki treatment the hands of the practitioner are placed with the fingers together on the patient. As energy is transferred from giver to receiver, the hands and the area treated become warm, which indicates a release of tension in the area and an increase in the blood flow. The head of the patient is treated first (four locations or positions), followed by the front (five positions) and back (five positions) of the body. Each position is held for 8 to 10 minutes (or less, if the practitioner is above first degree). Problem areas may be held longer until a result is sensed. The hand positions correspond to the energy points or chakras, identified in Hindu tradition, as well as other points. The treatment is completed with a series of general myofascial techniques, including kneading, counterforce, and stroking (effleurage), to close the energy channels.

As with other energy-oriented manipulative techniques, reiki requires significant verbal and nonverbal communication between the giver and receiver, who act in partnership. Permission must be granted both consciously and subconsciously for healing to be successful. Somatoemotional release is quite possible in this treatment.

Therapeutic touch, another form of energy work, was developed by Dr. Dolores Krieger (1992) and Dora Kunz in the late 1960s and early 1970s. In this style of bodywork, energy is directed through the hands of the “giver” (either on or off the body, usually off) to activate the healing process of the “receiver.” The therapist essentially acts as a support system to facilitate the process. Therapeutic touch treatments typically last 20 to 25 minutes and are accompanied by a relaxation response and a decrease in perceived pain. Although skeptics have claimed that this technique merely elicits a placebo effect (an interesting concept in itself), successes have been reported with comatose patients, patients under anesthesia, and premature infants.

Therapeutic touch posits that humans are open energy systems, bilaterally symmetrical, and that illness is the result of an imbalance in the patient’s energy field. The healer places himself or herself between the patient’s illness and the patient’s energy field to effect the healing process. The receiver must accept the energy of the healer and the necessity of change for the healing to occur. This should happen both consciously and subconsciously.

There are two phases of the treatment: assessment and balancing. Before balancing the practitioner “centers” himself or herself, entering a state of relaxation and awareness. The hands are moved around the patient’s body at a distance of 2 to 3 inches. The patient’s energy field is encountered and assessed by feeling for changes in temperature, pressure, rhythm, or a tingling sensation. Simultaneously, the practitioner nonverbally requests the permission of the patient to enter the patient’s field and effect a change. During the balancing phase the healer (sometimes referred to as the “sender”) then attempts to bring the two energy fields into a harmonic resonance through intent and visualization.

The attitude of the sender is one of empathy and compassion. The intent of the treatment is to facilitate the flow of vital energy, to stimulate it, to dissipate areas of congestion, and to dampen any areas of increased activity. In addition, the concept of rhythm and vibration is used, with color observed as a product of different frequencies within the field. At the beginning of the treatment, at the end of the treatment, or at both times, the practitioner “smoothes” out the patient’s energy field by running the hands from head to toe. This sometimes has a cooling effect and is referred to as unruffling.

Healing touch, as developed by Barbara Brennan (1988), is similar to therapeutic touch in that the healer seeks to balance the energy field of the patient. A specific sequence of techniques is used in which the healer encounters, assesses, and treats different layers of the patient’s visible “aura,” correcting any imbalances and smoothing out the field. Healing touch is somewhat more spiritually oriented that therapeutic touch, using techniques such as channeling and employing colors and crystals to assist in the process.

These “energy-based” techniques (in addition to many of the other techniques mentioned) emphasize the importance of psychoemotional cooperation and participation by the patient (i.e., the mind-body connection) for successful application. In addition, the mind intent of the manipulator comes into play as the director of his or her internal energy outward and into the patient. This concept is quite controversial by Western standards of scientific analysis.

Although critics refer to these and other manipulative techniques as “pseudoscience” because of a lack of supportive evidence, the power of the technique and of the mind are not to be undervalued. Clinical outcomes studies have indicated that the intent of both the patient and the clinician have a demonstrable effect in determining treatment outcome. This evidence sheds new and interesting light on the placebo effect as a real phenomenon (especially in light of the fact that placebos are “effective” in randomized drug trials about 30% of the time). It also indicates that treatment of the somatic component of disease can be approached effectively through acknowledgment of the “three-legged stool” model of the human: body, mind, and spirit.

FELDENKRAIS METHOD (AWARENESS THROUGH MOVEMENT, FUNCTIONAL INTEGRATION)

Moshé Feldenkrais (1904-1985) was an Israeli physicist who developed a system of movement and manipulation over several decades (Feldenkrais, 1991). The Feldenkrais method is divided into two “educational” processes. The first, awareness through movement, is a sensorimotor balancing technique that is taught to “students” who are active participants in the process. The students are verbally guided through a series of very slow movements designed to create a heightened awareness of motion patterns and to reeducate the CNS to new patterns, approaches, and possibilities (as in learning t’ai chi).

The second process is referred to as functional integration. This is a passive technique using a didactic approach, not at all unlike Trager table work (see discussion later in this chapter). The practitioner acts as “teacher” and the patient as “student.” The teacher brings the student through a series of manipulons to reestablish proper neuromotor patterning and balance. Manipulons are a manipulative sequence of information, action (as initiated by the practitioner), and response. They are gentle and are treated as exploratory, with the therapist introducing new motion patterns to the patient. Manipulons are referred to as “positioning,” “confining,” “single,” or “repetitive.” They can also be “oscillating.” In all cases the teacher plays a supportive and guiding role while creating a nonthreatening environment for change. Functional integration can be considered a combination of passive, articulatory, or functional techniques.

LYMPH DRAINAGE TECHNIQUES

Manual lymph drainage techniques incorporate application of light pressure to the skin and superficial fascia in a particular pattern that encourages an increase in the movement of lymph. In addition, lymphatic pumps are rhythmic techniques applied over organs, such as the liver and spleen, to increase drainage. The thoracic diaphragm is also sometimes used as a lymphatic pump, because movement of this structure creates increased abdominal pressure, which “pumps” the nearby cisterna chyli, a dilated portion of the thoracic lymph duct that serves as a temporary reservoir for lymph from the lower half of the body (Figure 16-7).

Figure 16-7 Lymphatic flow can be enhanced with manual lymph drainage techniques.

(Borrowed with permission from Chaitow L, DeLany J: Clinical application of neuromuscular techniques: practical case study exercises, Edinburgh, 2006, Churchill Livingstone.)

The hand stroke used in lymph drainage is distinctly different from effleurage. Effleurage that is applied in the direction of the heart can also increase the venous and lymphatic drainage of the involved structure(s). However, deeply applied effleurage can inhibit lymph movement and even result in damage to the lymphatic vessels, particularly if the region is already engorged with excessive lymph. Using very light pressure, lymph drainage applies a rhythmic short stroke that creates a short pulling action on the skin and superficial fascia, which is then abruptly released. A turgoring effect encourages the movement of lymph into the lymph capillary. The lymph then moves along the vessels, which empty into progressively larger lymph vessels, until the lymph eventually rejoins the vascular system at the subclavian veins.

Lymph drainage therapy is useful in a variety of clinical settings to encourage overall health and is profoundly useful in postsurgical and posttrauma care. The edema associated with sprains, strains, and a variety of sport injuries can often be quickly reduced with these techniques. The Vodder method of lymph drainage therapy and the Chikly method of manual lymph drainage are the two most popular methods in this highly effective and broadly applicable modality. Although the aims of the two methods are similar, the styles of application and of teaching are moderately different. Developers of both methods have published textbooks and journal articles to support their concepts.

MUSCLE ENERGY TECHNIQUE

Muscle energy technique (MET) can be applied directly or indirectly to individual muscles as well as to muscle groups (Chaitow, 2006). When MET is applied directly (i.e., toward the motion barrier, or in an attempt to lengthen a shortened or spastic muscle), the technique is based on the principle of reciprocal inhibition, which states that a muscle (e.g., flexor) reflexively relaxes as its antagonist (the associated extensor) contracts. Conversely, if a muscle in spasm is contracted against resistance and then relaxed, the effect often results in increased range of motion (ROM), or reduction of the motion barrier. This indirect application is based on the principle of postisometric relaxation (also known as postcontraction relaxation) (Lewit and Simons 1984).

This technique is one of the few “active” techniques in manual therapy, that is, the patient does the work. A distinction of MET is the amount of effort exerted by the patient. Usually, less than 20% of the total strength of the muscle is brought to bear during the interval of contraction. Another way of showing this is through the “one-finger rule,” in which the amount of force necessary is the force needed to move a single finger of the practitioner when the practitioner lightly resists the contraction. This is in contradistinction to the proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation technique often used in physical therapy, which employs a maximal muscle contraction and may expose the patient to risk of injury. A thorough knowledge of muscle attachments and their motion vectors is necessary to apply MET effectively and efficiently.

MYOFASCIAL RELEASE

Myofascial release is a gentle technique that uses knowledge of the physical properties of the fascia as it relates to muscles (Figure 16-8). Although some skill is necessary to apply this technique effectively, it is simple to learn and easily applied. The practitioner uses light and deep pressure, depending on the target structures, to palpate motion restriction within the fascia and moves toward or away from the restriction. The position is held until a “release,” or softening, is felt, the perception of which is the most difficult aspect of application. The tissues are then slowly returned to their original position. The release can be the relaxation of muscles, changes in the viscosity of the ground substance of the fascia, the slow breaking of fascial adhesions, or the realignment of the fascia to a more appropriate orientation.

Figure 16-8 A crossed-arm myofascial release (MFR) can be applied broadly to the tissues to alter the ground substance of the fascia.

(Modified from Salvo S: Massage therapy: principles and practice, ed 3, St. Louis, 2007, Saunders.)

Myofascial–Soft Tissue Technique

The myofascial–soft tissue technique is a combination direct-indirect massage technique for reducing muscle spasm and fascial tension. It is similar to pétrissage, except that more parts of the hand are typically employed. This technique can be used as a prelude to the high-velocity low-amplitude technique.

NEUROMUSCULAR THERAPY (NEUROMUSCULAR TECHNIQUES)

Neuromuscular therapy (NMT) is a precise and thorough examination and treatment of the soft tissues of a joint or region that is experiencing pain or dysfunction. As a medically oriented technique, it is primarily used for the treatment of chronic pain or as a treatment for recent (but not acute) trauma; however, it can also be applied to prevent injury or to enhance performance in sports.

NMT emerged on two continents almost simultaneously, but the methods had little connection to each other until recent years. In the early twentieth century, European “neuromuscular technique” emerged, primarily through the work of Stanley Lief and Boris Chaitow. For the last several decades, it has been carried forward through the writing and teaching skills of Leon Chaitow, DO. The protocols of North American “neuromuscular therapy” also derived from a variety of sources, including chiropractic (Raymond Nimmo), myofascial trigger point therapy (Janet Travell, David Simons), and massage therapy (Judith DeLany, Paul St. John). Over the last decade, Chaitow and DeLany (2002, 2008) combined the two methods in a two-volume text that comprehensively integrates the European and American™ versions. NMT continues to evolve, with many individuals teaching the techniques worldwide.

One of the main features of NMT is step-by-step protocols that address all muscles of a region while also considering factors that may play a role in the presenting condition. Like osteopaths, neuromuscular therapists use the term somatic dysfunction when describing what is found during the examination. Somatic dysfunction is usually characterized by tender tissues and limited and/or painful range of motion. Causes of these lesions include, but are not limited to, connective tissue changes, ischemia, nerve compression, and postural disturbances, all of which can result from trauma, stress, and repetitive microtrauma (stress due to work and recreationally related activities). Consideration is also given to nutrition, hydration, hormonal balance, breathing patterns, and numerous other factors that impact neuromusculoskeletal health. A distinct focus of treatment is the identification and treatment of trigger points, noxious hyperirritable nodules within the myofascia that, when provoked by applied pressure, needling, and so on, radiate sensations (usually pain) to a defined target zone (Figure 16-9).

Figure 16-9 Neuromuscular therapy (NMT) focuses attention on locating and treating trigger points (TrPs). TrP referrals from sternocleidomastoid can produce a variety of symptoms, including facial neuralgia, headache, sore throat, voice problems, hearing loss, vertigo, ear pain, and blurred vision.

(Borrowed with permission from Chaitow L, DeLany J: Clinical application of neuromuscular techniques, vol 1, ed 1, Edinburgh, 2008, Churchill Livingstone.)

Although the European and American versions have unifying philosophical threads, there are subtle, yet distinct, differences in the palpation methods. Both methods examine for taut bands that are often associated with trigger points and both use applied pressure to treat the pain-producing nodules. However, European NMT uses a slow-paced, thumb-drag method, whereas and NMT American™ version uses a medium-paced thumb or finger gliding stroke. There is also a slightly different emphasis on the manner of application of trigger point pressure release (specific compression applied to the tissues) for deactivation of trigger points. In addition, American NMT offers a more systematic method of examination and treatment, whereas European methods use less detail in palpation of deeper structures, preferring to incorporate positional release and other methods for the deeper treatment. European methods also focus significantly more on superficial tissue texture changes than their American counterparts.

Both European and American NMT support the use of hydrotherapies (hot and cold applications), movement, and self-applied (home care) therapies. Both suggest homework to encourage the patient’s participation in the recovery process, which might include stretching, changes in habits of use, and alterations in lifestyle that help to eliminate perpetuating factors. Patient education may also be offered to increase awareness of static and dynamic posture in work and recreational settings, and to teach the value of healthy nutritional choices. Referral to another health care practitioner may also be considered, especially when visceral pathology is suspected.

A successful foundation includes taking a thorough case history, including the patient’s account of the precipitating factors, and performing a complete examination of the soft tissues. Although many decisions will be individual to each case, the NMT protocols are performed while keeping a few basic rules in mind. Superficial tissues are treated before deeper layers, and proximal areas are treated before distal regions. Every palpable muscle in the region is assessed, not just those whose referral patterns are consistent with the person’s pain or which are thought by the practitioner to be the cause of the problem.

The first aim is to increase blood flow and soften fascia. Although gliding strokes are often the best choice, sometimes tissue manipulation (sliding the tissues between the thumb and finger to create shear) works better. Depending on the stiffness of the tissues, hot packs might be used to further encourage softening. Then the gliding strokes and manipulation can be repeated, alternating with the application of heat, or a few moments can be allowed in between for fluid exchange.

Once the tissues have become softer and more pliable, the practitioner palpates for taut bands. These bands, in which select fibers are locked in a shortened position, vary in diameter from as small as a toothpick to larger than a finger. At the center of the band there is often a thicker, denser area that is associated with trigger point formation.

Once the fiber center is located, it is evaluated for a trigger point, to which pressure is applied until a degree of resistance (like an “elastic barrier”) is felt. Sufficient pressure is applied to match the tension, which provokes or intensifies the referral pattern to the target zone. The applied pressure should be monitored, so that what is felt by the patient is no more than a moderate level of discomfort (7 on a scale of 1 to 10). Although the patient may feel some tenderness in the area that is being pressed, usually the focus is on the pain, tingling, numbness, burning, or other sensation in the associated target zone of the trigger point. The common target zones are usually distant from the area and are predictable. They have been well illustrated in numerous books and charts.

As the pressure is sustained, within 8 to 12 seconds the sensations being reported should begin to fade as the practitioner feels a softening of the compressed nodule or (rarely) a profound release. The pressure can be sustained for up to approximately 20 seconds, but longer than this is not recommended because this “ischemic compression” reduces blood flow.

Trigger point treatment (by pressure, needling, spray and stretch, or other method) can be repeated several times within the therapy session, with a few moments between each application to allow fluid exchange to occur. Each time treatment is reapplied, the practitioner should notice the need to increase the level of applied pressure to stimulate the same level of sensation. In some cases, the tenderness and referred sensations will be completely eliminated within one session.

As the final step, the fibers associated with the taut band should be lengthened. This might include passive or active stretching if the associated attachment sites are not too sensitive. If the attachments are moderately tender, inflammation should be suspected and elongation performed manually to avoid putting stress on the attachments. This can be achieved by using a precisely applied myofascial release or a double-thumb gliding stroke in which each thumb simultaneously slides from the central nodule to a respective attachment, applying tension to the band as the thumbs slide away from each other.

Specific training in the use of NMT protocols is necessary, because many contraindications and precautions are associated with NMT use. The protocols can be incorporated into any practice setting and are particularly useful when interfaced with medical procedures. Many complex conditions can benefit from the thorough protocols and treatment strategies used in NMT.

REFLEXOLOGY

In the Asian meridian system of the body, all the major meridians or channels are represented in the hands and feet. Because acupuncture is usually not done on the soles of the feet because of their sensitivity, a system of foot massage was developed in China. William H. Fitzgerald, who called it “zone therapy,” introduced this system to the United States in 1913. Now referred to by Dwight Byers and others as reflexology, the technique involves the application of deep pressure to various points on the hands and feet by the thumbs and fingers of the practitioner. The feet receive the preponderance of attention in this method, with various identified points not only corresponding to the energy channels of the body but also to specific organs and systems. When treatment is given, areas of tenderness or texture change are identified and pressure is applied. This has the effect of opening that channel and allowing body energy to flow unimpeded through its entirety. When all points are successfully treated, the energy system is flowing and balanced (see Chapter 19).

ROLFING AND OTHER STRUCTURAL INTEGRATION METHODS

Rolfing, a form of structural integration, was developed in the middle of the twentieth century by Ida Rolf. Rolf, who had a PhD in biochemistry, sought help from an osteopath after being dissatisfied with conventional medical treatment of her pneumonia. After this experience, Dr. Rolf embarked on a lengthy period of study, including yoga study, which resulted in the manipulative system that now bears her name (Rolf, 1975, 1997, Rolf and Thompson, 1989). In 1971, she founded the Rolf Institute of Structural Integration in Boulder, Colorado, which now trains and certifies practitioners of this style.

The theory of Rolfing is based primarily on physical consideration of the interaction of the human body with the gravitational field of the earth. As a dynamic entity, the human body moves around and through this field in a state of equilibrium, storing potential energy and releasing kinetic energy. In this system, form (potential energy) is in direct proportion to function (kinetic energy), and the balance between the two is equivalent to the amount of energy available to the body. In simple terms, the worse the posture, the more energy we consume on a baseline level, and thus the less we have available for normal activity. Furthermore, the physical energy of the body is in direct proportion to the “vital energy” of the person. Ideally, the body is always in a position of “equipoise,” but this is seldom, if ever, the case.

Rolfing traditionally involves a 10-session treatment protocol designed to integrate the entire myofascial system of the body. Photographs are taken of the patient before and after each session or at the beginning and end of a series of treatments to evaluate progress. The body is treated as a system of integrated segments consolidated by the myofascial system. Attempts are made through “processing,” as the treatment is called, to lengthen and center through the connective tissue system by a series of direct myofascial release techniques. As distortions in the system are released, the patient may experience pain. The pain experienced is not merely structural, however. It is thought that emotions are expressed through the musculoskeletal system as behavior, which is reflected in various postures and movement patterns (i.e., the widely accepted psychological concepts of pavlovian conditioning and body language). In other words, the musculoskeletal system is viewed as a link between the body and mind. Emotional or physical traumas are stored in the body as postures, which mirror a withdrawal response from the offending or painful agent. Over time, compensatory reactions occur, but the body ultimately decompensates (fails in adaptation to the imposed stresses), which results in somatic or visceral dysfunction. The direct technique seeks to put the energy of the practitioner into the system of the patient in an attempt to overcome the resistance to change embodied in the withdrawal response. As releases are effected through the treatment, the emotional component may also be expressed (i.e., a somatoemotional release).

The result of the treatment is a feeling of balance and “lightness” experienced by the patient. In addition, the patient should experience a heightened sense of well-being, because the treatment releases the effects of emotional trauma. Thus the feeling of lightness is more than simply an increase in the basal physical energy in the body; it is an increase in the body’s vital energy as well.

From Rolf’s work sprang a number of other systems of structural integration. Among those who developed their own styles, several stand out with innovative thinking. One of these, Tom Myers, a distinguished teacher of structural integration, suggests that we consider the body to be a tensegrity structure. Tensegrity, a term coined by architect-engineer Buckminster Fuller, describes a system characterized by a discontinuous set of compressional elements (struts) that are held together, and/or moved, by a continuous tensional network. The muscular system supplies the tensile forces that erect the human frame by using contractile mechanisms embedded within the fascia to place tension on the compressional elements of the skeletal system, thereby providing a tensegrity structure capable of maintaining varying vertical postures, as well as carrying out significant and complex movements.

Myers (1997) has described a number of clinically useful sets of myofascial chains. He sees the fascia as continuous through the muscle and its tendinous attachments, blending with adjacent and contiguous soft tissues and with the bones, providing supportive tensional elements between the different structures, and thereby creating a tensegrity structure. These fascial chains are of particular importance in helping to draw attention to (for example) dysfunctional patterns in the lower limb that may impact structures in the upper body via these “long functional continuities.”

Chaitow and DeLany (2008) note, “The truth, of course, is that no tissue exists in isolation but acts on, is bound to and interwoven with other structures. The body is inter- and intra-related, from top to bottom, side-to-side and front to back, by the inter-connectedness of this pervasive fascial system. When we work on a local area, we need to maintain a constant awareness of the fact that we are potentially influencing the whole body.”

SHIATSU (ZEN SHIATSU)

Shiatsu means “finger pressure” in Japanese. It originally developed as a synthesis of acupuncture and anma, traditional Japanese massage. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, anma became more associated with carnal pleasure and subsequently lost its place as a therapeutic practice. Shiatsu further diverged and became systematized in the twentieth century, with the Nippon Shiatsu School opening in the 1940s. Today, shiatsu is practiced worldwide in a multitude of practice settings. Although it has a strong root in energy-based medicine, the physical nature of its practice offers a quality more similar to massage than energy work.

As with other Asian-derived systems, shiatsu employs the meridian or channel concept of the human body. The points along the channels are referred to as tsubos (Japanese for “vase”). Shiatsu theory states that when a channel becomes blocked, the tsubos along it can express a “kyo” state (weak energy, low vibration, cold, open) or a “jitsu” state (strong energy, high vibration, heat, closed). The hands are used for three purposes: for diagnosis, for treatment, and for maintenance (to strengthen the newly attained balance).

During a shiatsu treatment the practitioner (or “giver”) uses acupressure to open or close jitsu or kyo tsubos, respectively. The technique is applied using the thumb, elbow, or knee, positioned perpendicular to the skin of the “receiver.” The body part used by the practitioner and the duration of application depend on the state of the tsubo. Acupressure is combined systematically with passive stretching and rotation of the joints to stimulate the flow of ki through the channels. Treatments are described for the whole body (basic) and for each of the 12 major meridians.

Several issues have been raised in this chapter in discussing the Asian styles of manual therapy that are also relevant here to shiatsu. The intertwining of body-mind-spirit is evident as a holistic method of treatment born of an ancient philosophy. The practitioner-patient (giver-receiver) relationship is one of partnership, because each is a participant in the healing process. This is born of the yin-yang principle (giver = yang, receiver = yin). The intention of the practitioner plays a major role in the effectiveness of the treatment; the giver is a nonjudgmental observer or plays an empathetic role. As opposed to the more neutral “do no harm” principle of Western caregivers, there appears to be more of a natural expression of love as a defined part of these systems (as with reiki). Intuition is also an important part of the treatment, because each session is an exploration of the process of healing and of the individuals involved (see Chapter 20).

SPORTS MASSAGE

Sports massage has emerged throughout the world as a valuable tool in prevention of and recovery from injury and for enhancing performance and increasing skills in the sport. Professional sports teams have long recognized the values of sports massage applications, employing athletic trainers, physical therapists, and massage therapists who often travel with the teams to administer care during the season and also work on team members during off-season. The practitioners are responsible for assessing the tissues using manual techniques, but also must consider the habits of use during the associated sport, determine which dysfunctional mechanics are actually useful adaptations by the body in response to stresses imposed by the sport, and incorporate particular strategies and methods of treatment and prevention of injury, depending on what is discovered.

It is important that the practitioner understand the biomechanics of the sport and the way in which the body might adapt to the imposed stresses. What might seem like a dysfunctional mechanic to be released in a nonsporting body might be a necessary or normal occurrence for that athlete. For instance, the external and internal ROM is often displaced posteriorly in a pitcher’s shoulder. This possibly occurs in the humeral shaft as a result of the torsional forces imposed on it through years of windup movements, particularly when these forces are placed on the youthful bone. If normal ROM tests are used, the external rotation would appear to be excessive and the internal would appear to be reduced, although overall the degree of ROM is the same as in a nonpitching shoulder. The uninformed practitioner might attempt to increase internal ROM, believing this to be reduced, and thereby destabilize the joint and overstretch the joint capsule, making the shoulder more vulnerable to injury.

Sports massage therapists often appear at neighborhood sport events to provide pre- and post-event massage. The techniques used warm up the tissues close to the time of event participation are significantly different from those used after the event to enhance recovery. Likewise, those used in the off-season to alter mechanics or those used in injured players differ from those used to prepare participants for play. It is important that the practitioner understand when to use which techniques, when ice and heat are appropriate, and just how much therapy is enough without overtreating the tissues. Professional sports massage training is suggested for all practitioners who work with athletes, whether in the field or in the clinic.

STRAIN-COUNTERSTRAIN

Strain-counterstrain (SCS) technique, originally called “positional release technique (PRT),” is a very gentle, passive technique developed by Lawrence Jones, DO. The practitioner usually palpates a muscle in spasm (often associated with strain) while the patient reports on his or her sense of discomfort. The patient is next brought into a position that shortens the muscle or eases the dysfunctional joint (counterstrain), which exaggerates the motion restriction. The patient then reports on the level of ease. This position is held usually for 90 to 120 seconds, and the patient is then slowly returned to the original position. The technique is designed to interrupt the reflex spasm loop by altering proprioceptive input into the CNS and can be followed by gentle stretching of the involved muscle. Tender points are also treated in this manner: the patient is brought to a position of ease, held in the position until a “softening” or change in tissue texture is felt or the tenderness subsides, then slowly returned to the original position.

Similar to SCS/PRT just discussed is functional technique (functional positional release), but the latter relies a little more on the practitioner’s palpation skills than on the patient’s reporting. The practitioner places a hand or finger on a tender area and searches for the most distressed tissue. The patient is then positioned until a “position of ease” is produced or until the discomfort is significantly reduced, and the patient holds this position for a certain period, usually at least 90 to 120 seconds and sometimes considerably longer. The patient is then brought slowly back to the original position. It is possible that as the position of ease reduces nociceptive and aberrant proprioceptive input to the CNS, an interruption of facilitation associated with pain and spasm is achieved. Realignment of fascia is also a result of the functional technique, and it is possible that the actin and myosin filaments are able to “unlatch” due to approximation of the two ends of the fibers.

TRAGER WORK (PSYCHOPHYSICAL INTEGRATION AND MENTASTICS)

Milton Trager, MD, was originally a boxer and gymnast and developed (almost by accident) his technique of psychophysical integration more than 50 years ago (Trager, 1994). To obtain the credentials he believed were necessary to bring his technique to the medical community, he obtained a medical degree from the University of Guadalajara in 1955. While there, he was able to demonstrate his technique and treat polio patients with a relatively high degree of success. After developing the technique over many years in his medical practice, he began to teach the method in 1975. The Trager Institute (Mill Valley, California) was founded shortly thereafter and is responsible for dissemination of information and certification programs.

Trager work is a two-tiered approach, along the lines of the Feldenkrais method (see previous discussion). The psychophysical integration phase, also known as “table work,” consists of a single treatment or a series of treatments. Mentastics, as described later, is an exercise taught to patients so that they may continue the work on their own.

Psychophysical integration is essentially an indirect, functional technique. The patient lies on a table, and the practitioner applies a very gentle rocking motion to explore the body for areas of tissue tension and motion restriction. No force, stroking, or thrust is used in this technique, merely a light, rhythmic contact. The purpose is to produce a specific sensory experience for the patient, one that is positive and pleasurable. Any discomfort serves to break the continuum of “teaching” and “learning.”

The focus of the treatment, however, is not on any specific anatomical structure or physiological process, but rather on the psyche of the patient. An attempt is made to bring the patient into a position (or motion) of ease, in which a sensation of lightness or freedom is experienced. This sensation is “learned” by the patient during the process of sensorimotor repatterning. In the words of Dr. Trager, the patient learns “how the tissue should feel when everything is right.” This mind-body interaction is the core of the treatment, in which the patient’s psyche is brought to bear on the CNS to break the feedback loop of pain → guarding → muscle spasm and induce a change. The result is deep relaxation and increased ROM (i.e., the sense of lightness).

Patterns of behavior and posture are learned during a person’s lifetime in part as reactions to trauma or withdrawal from pain, either physical or emotional (see discussion on structural integration). Initially, the body may be able to compensate for such reactions, but it will eventually decompensate, which results in various somatic or visceral symptoms. The Trager treatment “allows” the patient to reexperience what is normal through this exploratory process.

The practitioner seeks to integrate with the patient by entering a quasi-meditative state of awareness referred to as the “hookup.” This allows the practitioner to attend acutely to the work at hand and feel very subtle changes in tissue texture and movement, not unlike the level of attention necessary to practice cranial osteopathy (see later discussion). Without any specific anatomical protocol, the work is very intuitive, and “letting go” is necessary by both parties. The practitioner maintains a position of “neutrality” and makes no attempt to “make anything happen,” because it is actually the patient who is sensing and learning. The practitioner’s role is one of a facilitator, in which he or she seeks to provide a safe and nurturing environment for the patient to explore new and pain-free patterns of motion.

Mentastics, the continuing phase of Trager work, is short for “mental gymnastics” and follows table work. A basic exercise set is taught, and patients are instructed to practice on their own. These exercises consist of repetitive and sequential movements of all the joints, designed to relieve tension in the body. They are to be performed in an effortless, relaxed state of awareness, in which the individual “hooks up” with the self. The basic principles of Hatha Yoga and t’ai chi are used in these exercises. Once the set is learned, individuals can then continue to explore independently, creating their own custom-designed series.

Practitioners of Trager work have reported success (not necessarily cures) in patients with multiple sclerosis, muscular dystrophy, and other debilitating diseases. Athletes have also reported significant improvements in performance as a result of applying Trager techniques.

TUI NA

Tui na is a manipulative practice within TCM. The literal translation is “pushing and grasping.” Tui na, the forerunner of shiatsu in Japan, is more than 4000 years old and predates the manufacture of acupuncture needles. Tui na may be practiced by TCM physicians as part of their general practice, or they may specialize in it, as do members of the osteopathic profession.

As with the other Chinese medical arts, tui na is based on the meridian or channel view of the human body, the yin-yang principle, and the five elements theory. The organs of the body exist not only as anatomical structures, but also in a functional context (e.g., the “triple burner”), as well as in relation to one another. Yin and yang, as opposite forces, coexist in equilibrium with one another. Of the 12 major meridians of the body that correspond to the organs, six are yin, the others yang.

Qi, or vital energy, is a universal force that permeates everything. It is manifest as five separate elements: fire, wood, metal, water, and earth. The organs of the body are categorized accordingly. Qi flows through all the meridians once each day in 2-hour cycles. Therefore each meridian, and thus its associated organ, has its daily strong and weak periods. When the flow of qi is impeded in any channel, that organ or function may become dysfunctional, resulting in disease.

The techniques of tui na combine soft tissue, visceral, and joint manipulation. Typically, the patient is lying on a table or is seated. Soft tissue techniques, which are applied to the limbs, trunk, and head, precede joint mobilization to prepare the joint for movement and to relax the surrounding musculature. The techniques are designed to stimulate local blood flow, venous and lymphatic drainage, and the flow of qi (see previous discussion on shiatsu). These soft tissue techniques include the following:

Included in the joint manipulative techniques are the following:

Tui na can be applied to virtually anyone and has few contraindications. The existing contraindications are similar to those for massage, including skin lesions or infection, skin or lymphatic cancer, and osteoporosis. In addition, it is recommended that the low back and abdomen be avoided during pregnancy.

Anatomically, tui na is applied to the musculoskeletal system and viscera, with attention being paid to the meridians and flow of qi (as specific meridians flow through specific joints, muscle groups, and visceral structures). As with other forms of manipulative treatment, tui na seeks to produce a feeling of well-being and health in the patient. In addition, as the emotional and spiritual components of the patient are addressed, emotional release can also be produced.

VISCERAL MANIPULATION

Visceral manipulation generally involves specific placement of gentle manual forces to encourage tone, mobility, and motion of the abdominopelvic viscera and their supporting connective tissue. Although not indicated in patients with tumors or inflammatory disease, visceral manipulation can be useful in stabilizing and balancing blood flow and autonomic innervation and can even dislodge certain obstructions of the gastrointestinal system.

Methods that address manual manipulation of the viscera have been a component of some therapeutic systems in Oriental medicine for centuries and are now practiced extensively by European osteopaths, physical therapists, and other manual practitioners throughout the world. Osteopath and physical therapist Jean-Pierre Barral developed a system of training and practice of this technique that is available to all manual practitioners. Contact the Barral Institute in West Palm Beach, Florida.

OSSEOUS TECHNIQUES

In addition to methods applied to the soft tissues, a variety of techniques can be used to normalize the position of the osseous structure. Although some are discussed elsewhere in this book, the following are often used in conjunction with the afore-listed myofascial methods. Their inclusion as a supporting modality here is meant to encourage the synergistic integration of manual modalities.

Articulatory Technique

In the articulatory technique, the practitioner moves the affected joint through its ROM in all planes, gently encountering motion barriers and gradually moving through them to establish normal motion. This low-velocity moderate- to high-amplitude method would be considered a passive, direct/indirect, oscillatory technique used to restore as much motion as possible to a dysfunctional joint.

Cranial Osteopathy and Craniosacral Therapy

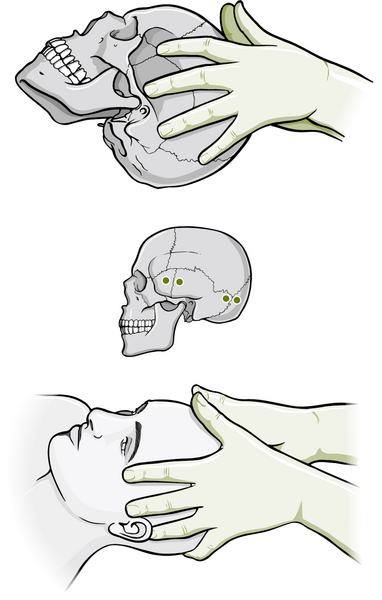

Cranial osteopathy (osteopathic techniques applied to the cranium) was developed by W.G. Sutherland in the mid-1900s. His work was based on the observation that the joints between the skull bones are meant to permit motion just as do joints in other areas of the body. While palpating these bones and joints, he discovered the existence of a very subtle rhythm in the body unrelated to respiration or cardiovascular rhythms. Sutherland named this rhythm the cranial rhythmic impulse (CRI). This impulse, he learned, was capable of moving the cranial bones through an ROM that, although very small, was palpable to well-trained hands (Figure 16-10). Cranial theory posits that there is inherent motility of the CNS, resulting in fluctuations of the cerebrospinal fluid, which bathes the brain and spinal cord. This fluctuation, in turn, moves the cranial bones through their small yet palpable ROM.

Figure 16-10 Vault hold for cranial palpation.

(Borrowed with permission from Chaitow L, DeLany J: Clinical application of neuromuscular techniques, vol 1, ed 1, Edinburgh, 2008, Churchill Livingstone.)

These concepts were expanded further in the 1970s by the findings of a research team at Michigan State University supervised by Dr. John Upledger. They discovered that the motion associated with this rhythm is not restricted to the cranial bones and proposed that, because the cranium is linked to the sacrum by the dural membranes, which cover the CNS, the motion is palpable in the sacrum as well. In addition, through the fascial-fluid system, this has effects all over the body. Motion restrictions in this system can be palpated and corrected (either directly or indirectly) through very gentle manipulation, also with global effects. Based on these concepts, craniosacral therapy emerged as a separate and distinct modality.

As releases are produced in this fascial system and throughout the body, memories (sometimes emotionally painful) can be reawakened and produce “somatoemotional release,” a form of mind-body connection. Clinical experience suggests that these experiences occur frequently, although it is not understood at this time whether this is due to the proximity of the membranes to the brain, stimulation of associated neural circuitry in peripheral tissues, or some other mechanism.

Cranial osteopathy has been controversial from its inception because of the lack of definitive, objective experimental evidence. Because research studies that could conclusively evaluate the effectiveness of cranial therapies have not been performed to date, evidence of effectiveness comes almost exclusively in the form of clinical case reports and testimonials. Successes have been reported in improving a variety of conditions, including chronic headache, cerebral palsy, autism, and behavioral disturbances. Data are now being gathered through outcome-based studies that lend credence to its effectiveness (Mehl-Madrona et al, 2007; Raviv et al, 2009).

Because of the time and effort necessary to develop this skill, relatively few osteopaths in the U.S. practice cranial osteopathy. The practice of craniosacral therapy, however, has expanded to other manual therapy fields, including chiropractic, physical therapy, massage therapy, and dentistry, with training being offered by the Upledger Institute (Palm Beach Gardens, Florida) and others.

High-Velocity Low-Amplitude Technique

The high-velocity low-amplitude (HVLA) technique is probably the most publicly recognized technique of the osteopath or chiropractor. This is a thrust-oriented technique designed to aggressively break through a motion barrier. More often than not, an audible pop is heard, the result of a brief cavitation of the involved joint. The HVLA technique can be applied directly (toward the barrier) or indirectly (away from the barrier), using short or long levers. Although often associated with manipulation of the spine, the HVLA technique can also be performed on the extremities.

Use of the HVLA technique is contraindicated in patients with osteoporosis, bone tumors, or severe atherosclerosis, and in those who are taking certain medications that make bones more brittle, such as many forms of chemotherapy. Recently, much discussion has focused on the safety of the HVLA technique when performed in the high cervical (neck) region due to potential risk to the vertebral artery. Controversy has expanded to include questions regarding the safety and accuracy of manual screening tests for vertebral artery insufficiencies (such as George’s Test and the DeKlynes Test). In March 2004, all U.S. chiropractic schools agreed to abandon the teaching and use of provocation tests such as these due to the inherent risks and high level of false data. An extensive PowerPoint presentation regarding these concerns is available (Clum, 2006).

MASSAGE THERAPY PRACTICE SETTINGS

Massage therapy is used in a variety of clinical settings, spas, private practices, and sport arenas. The expertise of the massage therapist or practitioner is essential in determining which techniques may or may not be appropriate and how the massage may be delivered. Application choices will also be based on the case presentation and may be influenced by the environment, such as a hospital or spa, as well as the allocation of time, prescribed therapy, or other associated modalities (e.g., stretching, exercise, biofeedback) that may be needed or desired. Massage is routinely applied to pediatric, adolescent, and geriatric patients. Frequently, massage therapists expand their therapeutic horizons by taking postgraduate study in other forms of bodywork or specific methods for application to certain pathologies. It is not uncommon to find a therapist who not only does Swedish massage but also employs Trager work, the Feldenkrais method, and craniosacral therapy, moving seamlessly from one to the other, as indicated by the response of the tissues and recipient.