CHAPTER 31 YOGA

The practice of yoga has spread from India and become popularized throughout the world. Over time, many different schools of thought and styles of practice of yoga have flourished. Although a few schools focus on the original deep spiritual aspects of yoga, many people understand yoga to be a posturing and breathing technique to induce relaxation. This is a preliminary aspect of it; however, the true practice of yoga goes deep into mysticism and occultism. The philosophy of yoga addresses some of the greatest mysteries of life and the universe as it deals with the obscure astral and spiritual planes of human existence. Yogic literature is replete with statements attesting that true yogic knowledge is “revealed” wisdom and that it cannot be learned by reading books, listening to lectures, performing postural exercises, or using breathing techniques. It is regarded as a secret knowledge that cannot be imparted by words, but only experienced through sincere and dedicated practice. This revealed wisdom is beyond the limits of the individual intellect and imagination. It is a knowledge that describes methods to achieve direct consciousness of Divinity and Reality through meditation and intuition. Although yoga viewed as a physical culture involving postural exercises and breathing techniques has provided tremendous benefit to the world as a means of relaxation, it is important for a holistic practitioner to have a preliminary understanding of the deeper spiritual aspects of the science of yoga. A review of the complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) literature reveals a scant amount of modern rigorous research on the benefits of the postural exercises and breathing techniques; but research into the mystical aspects of yoga using contemporary methodology is nonexistent. This chapter briefly discusses the history and philosophies of yoga.

Let us start with the definition of the word yoga. Yoga is a Sanskrit word that is derived from the root yuj, which means “union” or “to join.” This union is understood by the popular mind-body-spirit movement that has flourished recently to mean that the mind, body, and spirit are harmoniously joined together. Although this is partially correct, the real meaning is a union of the Jivatma (human soul) with the Paramatma (Divine Soul), or the merging of human consciousness with that of Divine Consciousness. The spiritual journey involves expanding the human consciousness until it is one with Divine Consciousness. To achieve this state of unification is considered to be the highest goal of human life, and this is the meaning of yoga. The mental process and discipline through which this union is attained is also called yoga. Thus, in essence, yoga is the ways and means of achieving the goal and it is also the goal itself. In ancient India, yogic scholars have experimented and developed methods of training and practice to efficiently help the interested seeker to achieve this goal. This experimental nature of the techniques is what makes yoga a true science of spirituality.

A problem that exists when discussing yogic philosophy is that it was originally written in Sanskrit. Many Sanskrit words and yogic philosophies do not translate perfectly into English. Some concepts in yogic literature do not have an equivalent in Western belief systems. Yogic science is a very specific and complex science. The difficulty in translating the concepts has led to many oversimplifications that have been detrimental to the true understanding of yoga. As yoga has spread throughout the world, various different schools of practice have evolved. Different techniques and methods have been developed over the years. Some schools continue to stress the importance of the true goal of yoga, whereas others have oversimplified the practice to focus on physical aspects of yogic techniques to improve balance and flexibility, induce relaxation, and so on. An in-depth evaluation of yogic science and the various different schools and styles of practice is beyond the scope of this chapter. Rather, this chapter focuses on explaining the fundamentals in a simple and succinct manner.

BACKGROUND AND HISTORY

The history of yoga starts around 1500 bc in the Indus Valley civilization that is now present-day India and Pakistan. Evidence of yogic beliefs and practices may be observed in the ancient Vedas, a collection of Sanskrit texts regarding “knowledge” of humanity, God, and the universe. According to Indian tradition, the Vedas were revealed through a vibrational medium (shruta) to seers (rishis) in the form of poems or hymns based on their mystical insights and are regarded as “revealed wisdom.” This wisdom was not heard and perceived by the intellect as is commonly understood, but was intuitionally felt at a subtle vibrational level. The yogic truths are based on the experiences of mystics, saints, and sages who have experienced them throughout the ages. In India, these individuals were referred to as rishis. Swami Vivekananda, an influential spiritual leader of the early twentieth century and authoritative expert on Vedantic knowledge, describes rishis as follows: “They who having attained the supreme soul in knowledge were filled with wisdom, and having found him in union with the soul were in perfect harmony with the inner self, they having realized him in the heart were free from all selfish desires, and having experienced him in all the activities of the world had attained calmness, . . . having reached the supreme God from all sides, had found abiding peace, had become united with all, had entered into the life of the Universe.” (Vivekananda, n.d.) (see also Chapter 7).

This mystical tradition continued to flourish in India, and in the period between 600 bc and about 300 bc, the Upanishads were composed, which further described philosophies pertaining to yoga such as paramatman (Divine Soul), atman (human soul), moksha (liberation), and dhyana (meditation). It was also around this time that the Bhagavad Gita (Song of the Lord) was written. The Bhagavad Gita discusses three key elements of yogic philosophy: karma (action), bhakti (devotion), and jyana (knowledge from introspection). The Bhagavad Gita illustrates the divine relationship between humans and Divinity. In 200 bc, the sage Patanjali compiled a history of oral tradition regarding yoga into the Yoga Darshan or Yoga Sutras, which give specific details of classic yogic practices.

FUNDAMENTAL CONCEPTS

To understand how yoga is a science of spirituality, it is important to understand the fundamental concepts that are a part of this system of beliefs. Yogic philosophy addresses the basic questions of human life: (1) Who am I? (2) Why am I here? (3) What is the nature of suffering? (4) What is the method of escaping suffering? Yogic philosophy basically deals with the nature of humanity, God, and the manifest universe and the relationship among the three. It also deals with the way our thoughts and actions influence our spiritual journey and details ways and means of bringing our thoughts and actions into a regulated state. Yogic philosophy asserts that this spiritual journey is germane to all human beings independent of race, class, intelligence, and so on, but exists as a latent phenomenon. The preliminary aspect of the journey begins when we begin to question the nature of our existence. The awakening of this dormant phenomenon occurs when we choose to undergo the quest to understand the nature of our existence, and the journey ends when we merge our consciousness with the Divine Consciousness.

A fundamental aspect of yogic philosophy is the belief that the cosmos is composed of two principal elements, purusha and prakriti. Purusha is composed of the Divine Soul and all souls of living things, including the human soul. Prakriti is the cosmic substance in the form of the physical world and the manifest universe. Human beings are composed of both purusha and prakriti, because their souls are a part of the Divine Soul and their outer selves are a manifestation of the cosmic substance in the form of the physical body. Prakriti does not have any conscious energy and exists in an inanimate state. The purusha is the Divine Soul, which is the animator of prakriti. The purusha is the source or base of everything in the manifest universe. Prakriti is the outer physical world and universe and our outer physical selves, including the body, mind, thoughts, and perceptions. The purusha is the substratum of all these things. All manifestations in the cosmos exist as a combination of both purusha and prakriti. Yogic philosophy states that essentially the human soul and the Divine Soul are the same. Through the process of human birth, the human soul becomes subjectively separated from the Divine Soul and must spend time in the manifest universe to make an attempt to become united with the Divine Soul again in consciousness. Yogic philosophy states that individuals are “bound” when they only identify themselves with prakriti, the outer self and the manifest universe, and are “freed” when they identify themselves with the purusha, the true inner self. In essence, yogic philosophy deals with the nature of God, humanity, and the manifest universe and the relationship between the three.

THE NATURE OF DIVINITY

Although yogic philosophy deals with God and soul, it is not considered to be a religious doctrine. It emphasizes that divinity is inside everyone and proposes scientific methods for achieving this realization. God is referred to by many different names, including Brahman, Purusha, Isvara, Paramatma, Nirguna Brahma, and Saguna Brahma, and there are subtle differences in the exact meanings of these terms. God is sometimes referred to as the Divine Soul who is without attributes. Different authors use the various terms interchangeably depending on the nature of the topic of discussion. At times God is referred to as a divine being with attributes, and the many names of gods of the Hindu pantheon are used as representations of God. However, the fundamentals of yoga refer to a divinity that is without attributes.

Many different schools of thought developed in yogic philosophy to describe the nature of God, either as a divinity without attributes or as a divinity with attributes. The two popular beliefs regarding the nature of God are embodied in the nondualistic and dualistic schools of thought. Adi Shankaracharya was a yogic scholar of the eighth century who expounded on the concepts of nondualism. The nondualistic philosophy states that the human soul and the Divine Soul are equal and the same. In the nondualistic school of thought, God is the Divine Soul that exists without attributes. The Divine Soul is said to be infinite, incorporeal, impersonal, unchanging, eternal, and absolute. The Divine Soul is the divine ground of all matter and sentient beings in the universe. Although the Divine Soul is the origin of all existence, forces, and substances in the material world, it is beyond the perception of the senses. It is this aspect of being beyond the perception of the senses that creates a difficulty in comprehending the experience of the Divine Soul. Because the Divine Soul is beyond the senses, it becomes difficult for the imagination to envision what this experience might be. The experience of the Divine Soul cannot be described, but is often termed Sat-Chit-Anandam (Infinite Truth, Infinite Consciousness, Infinite Bliss).

The Divine Soul is formless and attributeless and cannot be described to be this or that. The problem arises when humans try to offer devotion or attempt to surrender to a God without attributes. Yogic methods attempt to achieve conscious awareness of this Divine Soul without attributes, but to wrap the human mind around an entity that is without form and function is quite difficult. This difficulty led to the birth of the dualistic school of thought. Because an attributeless God is difficult to fathom, the dualistic school of thought describes God to be with attributes. The purpose is to create an object of devotion that the human mind can perceive. The various gods of the Hindu pantheon represent different deities with godly attributes used by yoga followers to offer devotion and practice self-surrender. Over time, different sects and schools developed, each with its own personal deity. Also, certain schools have chosen a guru or spiritual teacher to be their object of devotion. This technique has been said to be a very efficient method of progressing on the spiritual journey, provided that the guru is one of the highest caliber who is merged with Divine Consciousness.

As noted, the nondualistic school of thought states that God is the substratum that courses through all souls and substances in the cosmos, and that there is no difference between the Divine Soul and the human soul. The dualistic school interprets the relationship between God, humans, and the universe differently. The dualistic school of thought states that differences exist between God, the human soul, and the manifest universe. Regardless, both schools of thought hold that even if a God with attributes in the form of a deity or guru is used as an object of devotion, the real ultimate God is an absolute divinity without attributes. In the end, the differences in the two schools of thought may be only a matter of semantics, because both claim that the goal of life is to merge the individual human soul with the Divine Soul.

THE NATURE OF THE MANIFEST UNIVERSE (PRAKRITI)

Yogic philosophy describes the origin of matter and the different phenomenon inherent to matter that make up the manifest universe. It states that in the beginning there was nothingness. Then a primordial stir occurred that sent out a wave of creation. This primordial stir is said to have been the awakening of the dormant will of God. From this primordial stir came the existence of prakriti (the manifest universe). When matter at its most primal subatomic state came into existence, so did its sense of individual identity apart from other forms of matter and apart from the Divine Consciousness. This is the basis of ego, or the “I-am-ness” of matter. As the complexity of physical matter evolved, so did the complexity of the individuating principle. Matter evolved to become the various objects and beings in the universe. The individuating principle evolved to include not only ego, but also intellect, mind, and consciousness.

Yogic philosophy details the creation of the manifest universe. It evolved from the basic subatomic particles to grosser and denser entities. Further complexities of the manifest universe include the five subtle potential energies of nature: sound potential, touch potential, sight potential, taste potential, and smell potential. These subtle potential energies correspond to the five fundamental elements of nature: ether/space, air/force, fire/energy, water/liquid, and earth/solid. This phenomenon of the five elements is also seen in other spiritual movements of the East and in Ayurvedic medicine and Chinese medicine. These five elements are related to the five “organs” of sense: hearing, feeling, seeing, tasting, smelling. To interact with the physical world, the five “organs” of action came into being: expressing, performing tasks, moving, excreting, and procreating. As matter evolved to denser and denser forms, it became the manifest universe with all matter and living beings. The variety of objects and creatures of the world are all composed of different proportions of the five potential energies and the five elements of nature.

Humans, including their organs of sense and organs of action, are also a combination of the subtle potential energies and elements of nature. The human being, in essence, is a microcosm of the macrocosm of the universe. Human beings interact with the phenomenal world through the organs of sense and organs of action. When humans attach themselves to the phenomenal world that they perceive with the senses and manipulate by action, they subjectively experience the pleasures and pains associated with this attachment. So in one sense, it seems that nature serves to keep humans hidden from their real selves by keeping them involved in the complexities of the material world. However, yogic literature says that the true purpose of nature is to provide the necessary experiences for the unfolding of the human being’s higher consciousness. It is humans’ ignorance (avidya) of their inner selves that binds them to the material world and its objects. This perception is referred to as maya, the illusory manifest universe. Taking the inner journey and gaining conscious awareness of the inner divinity in themselves, humans break free of the complex illusory power of the manifest universe. When the association with maya is removed, the condition of spiritual liberation (moksha) can take place.

THE NATURE OF HUMANITY

Humans are composed of both purusha and prakriti. As purusha, humans contain a portion of the Divine Soul in the form of the human soul. As prakriti, they contain a portion of the manifest universe in the form of the physical outer coverings of the body. In a simplistic sense, it appears that the physical body is the only covering to the human soul, but in reality the human soul is hidden under innumerable coverings. The spiritual journey of human beings involves increasing the consciousness to move from the outer physical body through these innumerable coverings to get to the divinity of the inner self. As these layers are traversed, an intuitional knowledge “reveals” itself, and the individual gets an opportunity to experience the soul. An essential element of the mystical practice of yoga is to remove these coverings layer by layer. Although there are innumerable layers or coverings to the soul, the human being is said to be composed of three bodies: the physical body, the astral body, and the causal body. This is similar to the traditional Chinese medicine view that the human being is composed of the physical body and the ethereal body.

The outer body is the physical body, which is a component of the manifest universe and is made up of the five basic elements of nature. The outward aspects of the physical body result from the mixture of the genetic components of the mother and the father. The physical body goes through the changes of life as it is born, grows, decays, and then dies. At death, it is meant to return to nature to reenter the food cycle. The physical body contains the five organs of sense and the five organs of expression that interact with the material world. Yoga states that there is a fundamental unity among all living creatures and all that exists in the universe. Yoga stresses the importance of the physical body’s living in cosmic equilibrium and harmony, because we affect our surroundings and our surroundings affect us. The steps recommended for achieving this equilibrium include eating a simple natural diet, avoiding indulgences, and taking only the minimum from nature to maintain our existence. The practice of yoga attempts to bring about this harmony by bringing the physical body under the conscious control of the mind. When this is achieved, the body can enable higher spiritual pursuits. The physical body is the grossest part of the human body, and each successive layer has a greater subtlety to it.

The middle body is the astral body composed of prana (life force), manas (mind), buddhi (intellect), chit (consciousness) and ahankar (ego). Every living being has an astral body. The astral body is connected to the physical body through the layer of prana from which vital energies flow to the physical body. The layer of prana of the astral body has a shape similar to that of the physical body, but is more subtle than the physical body. Prana is the subtle life force that courses through the astral body. It is similar to the qi or chi of ancient Chinese beliefs. Prana exists in every form of matter in the manifest universe. As has already been said, prakriti or matter is inanimate and needs purusha to activate it. Prana activates matter by linking matter to energy on the physical level. The physical body is inanimate without the currents of prana. Prana is often referred to as “breath,” but it is actually the force or energy that keeps up the activities of the physical body. The currents of prana flow along well-marked channels into every organ and part of the body. There are over 72,000 nadis (subtle energy channels) through which prana flows. These should not be confused with the nervous system, which is part of the physical body. The channels of prana have a very close similarity to the meridians of acupuncture. All matter in the manifest universe has a layer of prana, and the physical world is dependent on this flow of energy. Similarly, the physical body is also dependent on the flow of energy from the layer of prana. When prana ceases to function, the physical body dies.

Beyond the layer of prana is the layer of the mind. The mind should not be construed to be the brain. The brain is part of the physical body, whereas the mind is part of the astral or ethereal body. In an unregulated state, the mind produces spurious thoughts, both positive and negative. The input from the five senses also influences the quality and wandering nature of the mind. The mind does not involve reflexive reaction, such as moving one’s hand away from a hot object. Such reflexive actions are part of the brain and nervous system, which exist in the physical body. The mind’s activity moves in an unregulated manner when the individual associates himself or herself with the outer physical body and the feelings of comfort, joy, misery, and sorrow that accompany this association. As this association becomes stronger and stronger, the power of the mind keeps the individual’s consciousness unaware of the inner human soul. Through sincere and dedicated spiritual practice the mind can be regulated. In a regulated state, the mind can be trained to look inward to ascertain the nature of the soul. When the mind is regulated, it becomes the most powerful vehicle for the spiritual journey. As the process of creation of the manifest universe occurred, the individuating principle of the mind also spread throughout this universe. Yogic theory states that the human mind is related to this Universal Mind and has latent functions and powers similar to those of the Universal Mind.

Beyond the layer of the mind is the region of consciousness, intellect, and ego. Although the words mind and intellect are used, these words are not perfect translations from the Sanskrit words manas and buddhi. In yogic knowledge, the mind and intellect are not part of the brain. The brain is part of the physical body. The mind and intellect are part of the astral body, and they are more subtle than the prana. Beyond the mind and the intellect is the ego. The term ego does not correlate with the traditional usage of the word in Western psychology. It is not the ego of Freud’s id, ego, and superego theory, nor is it the part of the human mind from which conscious urges and desires arise, nor an inflated feeling of self-pride or superiority to others. The ego in yogic theory refers to the sense of “I-am-ness.” In the densest form of ego, it is the “I-am-ness” of the material world in which we associate ourselves with our professions, our hobbies, our likes and dislikes, our ties to others, and so on. In the subtlest form of ego, it is the “I-am-ness” of the human soul feeling separated from the Divine Soul.

The third body is the causal body, which houses the human soul. Yogic theory states that all our actions and thoughts create a causal effect on the outside world and also on our causal body. These subtle impressions produced by all our thoughts and actions create coverings around the soul. They control the formation and growth of the other two bodies and determine every aspect of our lives. Beyond these coverings is the soul, which is indestructible and unchangeable. The soul remains a passive onlooker to all the activities of life. At the time of death, both the causal and astral bodies (which remain together) separate from the physical body. The physical body disintegrates into the five elements to reenter the food cycle. If in this lifetime the human soul does not achieve merger with the Divine Soul, the causal body and astral body become reincarnated.

Yogic theory discusses the phenomenon of reincarnation. At the time of death the physical body dies and returns to the basic five elements of nature. The soul, which is trapped in the causal and astral bodies, takes another journey. Liberation (moksha) is the condition in which the individual’s consciousness has evolved to an extent that the individual is freed from the cycle of birth and death. If the condition of liberation is achieved in this lifetime, the soul is spared from the cycle of birth and death. If the individual does not achieve liberation, the soul along with the causal body, astral body, and all the impressions from past thoughts and actions come back to the manifest universe to take up another life. A belief in the theory of reincarnation is not required to practice yoga, because the goal of yoga is meant to be achieved in one’s current life.

PATANJALI’S YOGA SUTRAS

Sage Patanjali is credited with compiling the philosophy of yoga into the Yoga Sutras. This book deals with the definition of yoga, the goals of yoga, the obstacles on the path of yoga, and the ways and means of achieving the goals. Patanjali also describes the different stages of progress and the different stages of consciousness that are achieved with steady progress. According to I.K. Taimini (1961), Patanjali describes the obstacles that distract the mind as being disease, languor, doubt, carelessness, laziness, worldly-mindedness, delusion, nonachievement of a stage, and instability.

Patanjali defines the goal of yoga as chitta-vritta-nirodha, which translates as “inhibition of the fluctuating states of mind” or “whirlpools” of the mind. When the mind is regulated and exists in a state of stillness, the individual experiences his or her consciousness in its essential and fundamental nature. When the mind is unregulated, the individual’s consciousness is assimilated into the various fluctuating states of the mind. The five fluctuating states of the mind are described as (1) knowledge from direct cognition, (2) knowledge from a false conception, (3) experience based on fancy or imagination, (4) sleep, and (5) experience based on memory. To achieve a state of stillness in the mind, the fluctuating states of the mind need to be regulated. Suppression of the fluctuating nature of the mind is the goal of yoga.

You can try a brief exercise to illustrate the difficulty of achieving a stillness of the mind. Try to examine the contents of your mind without making any particular effort for 5 minutes. Try to catalogue the varying fluctuations of the mind. For most, it will be difficult to go even a few seconds without the mind’s being involved in one of its five states. The rapidly changing mental images that present themselves are derived from the ever-changing impressions produced by the outer world through the vibrations impinging on the sense organs, memories of past experiences floating in the mind, and mental images connected with anticipations of the future. Meditation is the vehicle that allows one to develop the ability to suppress the modifications of the mind, so that one can experience one’s true inner self.

Patanjali also details the afflictions (kleshas), obstacles on the path to attaining the goal of yoga, that must be overcome for the spiritual aspirant to progress on his or her spiritual journey. Yogic philosophy also states that these afflictions or obstacles are the root cause of human suffering. The five obstacles are ignorance, egoism, attraction to specific people or objects, repulsion toward specific people or objects, and the strong desire to continue living or a fear of death. Ignorance refers to a lack of awareness of the inner divinity and is the root cause of all of the other afflictions. Ignorance is not lack of knowledge, but refers to a spiritual ignorance in which the individual takes the material world to be Reality and remains ignorant of his or her true inner divinity. This leads to egoism or “I-am-ness,” in which the individual’s consciousness associates itself with the physical body and its sense organs, which experience the manifest universe (prakriti). This is when the individual becomes “bound” to prakriti. As this involution progresses, the association of the consciousness with the physical body and the illusory objects surrounding it becomes strengthened. Then, the individual starts to associate the pleasures and pain the individual experiences with the illusory objects of the manifest universe. This leads to a sense of attraction or repulsion toward objects and persons that cause pleasure and pain. This attraction and repulsion to innumerable persons and things in the manifest universe condition the individual’s life, and the individual begins to think, feel, and act according to the biases produced by these bonds. Yogic philosophy states that when the individual is bound to these attractions and repulsions, the person curtails his or her individual freedom. This binding is considered to be the cause of most of human misery. The last obstacle is a strong desire for mortal life or fear of death, which results from the compounding effects of the first four obstacles. A sincere and dedicated practice of yoga is the means for attenuation of these obstacles on the path to realization. As one progresses on the spiritual journey through yoga, there is a reduction of the obstacles, which leads to a reduction of the detrimental effects these obstacles have on meditation and progress on the spiritual path.

As one progresses and evolves along the spiritual path, the subtle essence of one’s inner nature slowly reveals itself. Yogic literature states that with some spiritual progress, the mind becomes regulated, and its capacity for higher functions and greater levels of consciousness grows. The sincere spiritual aspirant can use this regulated mind and turn its attention inward to understand the nature of the manifest universe, the Divine Soul, and his or her true inner self. As this understanding of the relationship between prakriti and purusha unfolds, the individual mind begins to understand the functions of the Universal Mind. When this occurs the mind can become harnessed to develop certain powers (siddhis). The powers described by Patanjali include clairvoyance, knowledge of past and future, telepathy, communication with previously liberated souls, extraordinary strength, and so on. Patanjali stresses that although one may acquire these powers, the sincere spiritual aspirant should shy away from these powers. They serve as temptations and distractions along the journey, and the aspirant should remain focused on the true goal of yoga. Patanjali states that these powers become manifest as consciousness expands, but the spiritually adept aspirant also gains the wisdom not to misuse these powers.

PATANJALI’S RAJA YOGA

Raja Yoga, or “kingly yoga,” was detailed by Patanjali in his Yoga Sutras. He describes Raja Yoga as an efficient means of achieving the goal of yoga. Raja Yoga is a systematic method used to achieve a state of stillness in the mind. It consists of eight steps or limbs and is sometimes referred to as Ashtanga Yoga. The eight steps are progressive stages of practice to enable successful meditation and realization of the goal. The steps systematically reduce the obstacles on the path to self-realization. In Raja Yoga, the method adopted for bringing about changes in consciousness is based essentially on regulation of the mind by the will of the individual. This leads to a gradual suppression of the fluctuating and wandering nature of the mind. The techniques of Raja Yoga enable the gradual elimination of all sources of disturbance to the mind, both external and internal. With progress, the mind becomes regulated and is able to achieve the stillness that is required for further progress. The eight steps of Raja Yoga are as follows:

OTHER YOGIC PRACTICES

Patanjali’s Raja Yoga is the oldest practice of yoga that has been documented. Over time, different practices have come into existence. The Bhagavad Gita describes three other paths of yoga: Karma Yoga (yoga of action), Bhakthi Yoga (yoga of devotion), and Jnana Yoga (yoga of knowledge from introspection). Patanjali’s original Raja Yoga incorporated these elements of yoga, but did not recommend practicing them exclusively. Hatha Yoga is the other yogic movement that has become popularized over the years. It deals mostly with the postural aspects of yoga. Today, there are innumerable schools of yoga, each emphasizing different aspects of practice. However, the key elements of universal love and tolerance, surrendering to the will of the Divine, and devotion to the Divine are germane to all paths. Interested individuals should take caution in picking a path that suits their stage in life and fits their spiritual goals. At the same time, individuals should note that the true goal of yoga is to merge the inner self with the Divine Self. As the Bhagavad Gita says, “A person is said to have achieved yoga, the union with the self, when the perfectly disciplined mind gets freedom from all desires, and becomes absorbed in the self alone.”

Karma Yoga

Karma Yoga describes the performance of actions (karma) in a selfless service to God as a means of achieving merger with the Divine Consciousness. Actions should be performed in remembrance of God without anticipation of reward or failure. This should become a continuous process and include all activities of daily life, such as eating, caring for children, and so on. When this practice becomes established as a continuous process, it becomes like meditation in which the individual is continually absorbed in the remembrance of God. The individual begins to think of himself or herself only as an instrument of the Divine Consciousness, and no longer considers himself or herself the doer of actions. As this stage progresses, the individual loses attachment to the work and the antecedent joys and sorrows associated with the work. As the individual surrenders to the will of the Divine Consciousness, his or her will strengthens, and the individual is able to achieve things beyond his or her self-imposed limitations. In Karma Yoga, the individual lives and works in a harmonious manner with the outside world. The person performs his or her duty in such a way that this work becomes a spiritual practice.

Jnana (Gyana) Yoga

Jnana Yoga is the path of knowledge. This path aims at attaining Divine Consciousness through studying sacred books and engaging in deep inquiry and contemplation of the eternal truths. It involves recognizing God as the Creator of the Universe; the Almighty, Omnipotent, Omnipresent, and Omniscient One; and the Source of all spiritual knowledge. The knowledge obtained through this yoga helps a person understand the true nature of God, soul, and prakriti. This enlightenment enables the individual to break attachments to material things and allows the soul to become awakened so that it may merge with the Divine.

Bhakthi Yoga

Bhakthi means “devotion,” and Bhakthi Yoga is based on complete love of and devotion to God or Divine Consciousness. The object of devotion can be any deity or divine incarnation, or one’s guru (spiritual teacher). Through constant devotion, the aspirant discovers Divinity reflected in every aspect of living and in every part of the universe. As the individual sees Divinity in everything, his or her capacity for love grows, and the individual is able to develop universal love and tolerance. Through love and devotion, the aspirant’s ego or “I-am-ness” becomes subjugated, and the aspirant feels everything to be a part of the Divine.

Hatha Yoga

Hatha Yoga was developed in the fifteenth century by Yogi Swatmarama. He compiled his teachings into the Hatha Yoga Pradipika. Hatha Yoga uses physical purification as a means to purify the mind. Compared with the seated asanas of Patanjali’s Raja Yoga, which were a means of preparing for meditation, the asanas of Hatha Yoga were developed as full body postures. Hatha Yoga also describes the various nadis and chakras of the astral body and details methods used to awaken these centers. Hatha Yoga in its many modern variations is the style that most people actually associate with the word yoga today. Unfortunately, many of these branches have ignored the deeper spiritual planes of this yoga and are satisfied with the physical health and vitality that its practice brings. In some schools, Hatha Yoga has been reduced to another form of fitness training.

Meditation

All of the yogic practices do eventually include meditation, which is the point at which all paths seem to converge. Yogic philosophy has influenced other spiritual movements, including Sufism, Buddhism, Sikhism, and Kaballah. Even these different movements also include meditation as an important part of the practice. Interestingly, the Chinese word chan and the Japanese word zen are derived from the Sanskrit word dhyan, and all these words refer to meditation. Meditation is said to be the vehicle used to travel on the spiritual journey. It is through meditation that higher states of consciousness unfold. It is also said that through meditation the various supernatural powers become manifest in the individual. Yogic literature states that the effects of meditation do not last just during the time spent meditating. The effects start to permeate throughout the day and influence all aspects of life. The goal of meditation is not just to experience the effects of meditation, but through it to achieve a condition in which the individual feels connected to the Divine throughout the day. Consider, for example, a quote from the Great Master Shri Ram Chandra Maharaj of Shahjahanpur, who founded the Sahaj Marg system of spiritual practice: “The real state of samadhi is that in which we remain attached with Reality, pure and simple, every moment—no matter how busy we may be all the time with worldly work and duties. It is known as sahaj samadhi—one of the highest achievements, and the very basis of nirvana. Its merits cannot be described by words, but can be realized by one who abides in it.”

Yogic literature describes many different techniques for meditation. Some schools of yoga advocate a visualization technique using the form of their deity or their guru as the object of meditation. An effective yogic method is described in which the aspirant chooses to use a capable guru as the object of meditation, provided that the individual has developed love and devotion for the guru and surrenders himself or herself to the will of the guru. Patanjali describes several different techniques of meditation, including meditation on the heart, which is said to be an effective method for understanding the nature of the mind and for developing a sense of universal love. Patanjali also describes meditative techniques to improve intuitional capacity as well as methods to develop some supernatural powers such as clairvoyance. Another common method for meditation is the use of sacred sounds or mantras. The primordial stir or vibration of the universe is said to be articulated as “OM (A-U-M),” which is a very popular mantra used in meditation. One mantra technique is to meditate on the sacred sound OM by mentally repeating the sound in the mind. With time and practice, the mind becomes naturally integrated with the mantra and reverberates with the sound of the mantra. This renders the mind still and enables deeper states of meditation.

STAGES OF THE SPIRITUAL JOURNEY

Regardless of which path an individual chooses, the goal of yoga remains the same. Although the outer trappings of the paths may be different, there are certain stages common to all paths. After some preliminary progress, there exist four stages of which the aspirant must gain understanding and which must be incorporated into the aspirant’s life. These four stages must be attained by every individual regardless of the chosen path. These are compulsory if the aspirant is genuinely interested in achieving the true goal of yoga. The four stages or conditions to be achieved are viveka, vairagya, shat sampat, and mumukshutva.

The first step is the acquisition of viveka. Viveka is the power of discrimination, which means the ability to discriminate between the real and the unreal, between the permanent and the impermanent, between that which is the inner self and that which is not of the inner self. As the individual progresses on the spiritual journey, the power of discrimination grows stronger, and the individual gains inner strength and mental peace. The state of viveka becomes more and more a permanent condition. This allows the individual to deal efficiently with the material world, because the individual always remains alert and does not become entangled in the trappings of the world.

The second step is the acquisition of vairagya, dispassion or nonattachment. An individual without vairagya is a slave to the attractions and repulsions of worldly life. When the aspirant gains the state of vairagya, the aspirant is not bothered by the attractions and repulsions of the material world. This aids concentration of the mind and generates a strong yearning for liberation. Vairagya does not imply that the spiritual aspirant should abandon the social duties and responsibilities of life. Rather, the individual is to attend to them as a service to the Divine. Theoretically, it is easy to talk of viveka and vairagya, but the practical application of the two on a continuous basis can be difficult. With continuous sincere, dedicated effort, the condition of viveka and vairagya can exist as a natural part of the individual.

The third requisite is shat sampat, or sixfold virtue, which brings about tranquility and regulation of the functions of the mind. The six virtues are as follows:

The fourth necessary stage is mumukshutva, which is an intense desire for liberation. In this condition, the aspirant’s attention is permanently fixed on the goal of achieving union with the Divine. To attain this stage, the spiritual aspirant must have equipped himself or herself by progressing through the first three stages. The order of achieving these stages is important, because one leads to the other and they culminate in the development of an intense desire for liberation.

INNER AWAKENINGS

The goal of yoga is to merge the human soul with the Divine Soul. The journey to this goal involves progressing through various stages of consciousness. The four stages described earlier are also part of this journey. As the consciousness expands, there is also another journey that takes place. This is the journey of the currents of prana in the astral body. Yogic literature describes the journey of the consciousness and the journey of the currents of the astral body in great detail. The journey of the currents of the astral body involves the nadis and chakras.

Nadis and Chakras

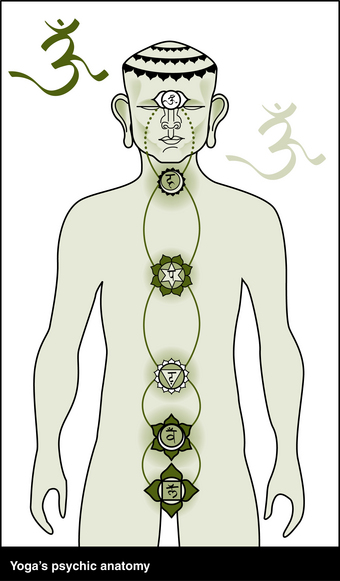

Nadis are the channels through which the prana (life force) of the astral or ethereal body are said to flow (Figure 31-1). Prana is related to the qi or chi in Chinese-based systems, and the nadis seem to correspond to the meridians of traditional Chinese medicine. As noted earlier, there are over 72,000 nadis (subtle energy channels), and the places where multiple nadis merge form chakras. A chakra is defined as a center of activity that receives, assimilates, and expresses the prana (life force). The human body is said to contain seven chakras that are aligned in an ascending column from the base of the spine to the top of the head. Although they appear to be in the spinal column, the nadis and chakras exist only in the astral body and are not actually part of the spinal column, which is a part of the physical body. The seven chakras represent various aspects of consciousness. They are described as having different colors and are visualized as lotuses or flowers. As the spiritual journey progresses, the different chakras begin to become awakened as deeper levels of spiritual subtlety are achieved.

Although there are over 72,000 nadis, the three main ones are the ida, pingala, and sushumna nadis. The sushumna nadi starts at the base of the spinal column, moves straight up the body, and terminates at the top of the head. The ida and pingala nadis also start at the base of the spinal column, but they crisscross, forming semicircular curves. The journey of the chakras starts with the awakening of the kundalini shakthi, which lies dormant at the base of the ida, pingala, and sushumna nadis at the base chakra, the muladhara chakra. The kundalini is likened to a sleeping serpent coiled at the base of the spine. As the spiritual journey marches forward, the kundalini becomes awakened and starts to move up the ida, pingala, and sushumna nadis. As it travels up these nadis, it awakens the chakras along its path. As successive chakras are awakened, they correspond to higher states of consciousness, culminating at the top, which represents the Divine Consciousness. The seven chakras are the following:

Many different texts offer different descriptions of the chakras. Some declare that each chakra has its own color, and some state that each chakra has its own vibrational sound. The chakras are also described as relating to different emotions. For example, awakening of the anahata (heart) chakra is associated with increased capacity for love and tolerance. We can get a very preliminary understanding of the chakras by reading about them, but yogic literature asserts that true knowledge of a chakra can be achieved only by the awakening of the chakra in the individual. Although many yogic practices focus on awakening the kundalini and taking the journey from the muladhara chakra to the sahasrara dal kamal, there are other inner journeys described in the yogic literature. For example, the Sahaj Marg system of spiritual training starts with the heart chakra and describes levels of spiritual attainment that goes far beyond the sahasrara dal kamal chakra.

IMPORTANCE OF THE GURU

Adi Shankaracharya, who expounded on the philosophy of nondualism, states, “These three things are hard to achieve, and are attained only by the grace of God: human birth, the desire for liberation, and finding refuge with a great sage.” In fact yogic literature is replete with statements attesting to the importance of finding a capable guru in undergoing the spiritual journey. Guru Nanak, who founded the Sikh movement, says on the importance of a guru, “Let no man in the world live in delusion. Without a guru none can cross over to the other shore.”

The word guru comes from Sanskrit, and its roots are gu, meaning “darkness,” and ru, signifying “dispeller.” A guru is an awakened being who has merged his or her consciousness with that of the Divine. By an application of will, the guru is able to transmit this higher consciousness to the aspirant, thereby removing the darkness enveloping the aspirant’s awareness. The spiritual path is long and fraught with obstacles of desire and ego, along with the individual’s own delusions, fears, prejudices, fixations, and stagnant tendencies. A guru is a spiritual teacher who guides the aspirant on the spiritual path and helps to remove these obstacles. The guru devotes his or her life to guiding the aspirant along the spiritual path, the summation of which is the realization of the inner self and merging of the inner self with the Divine Self. Just as the nature of spirituality is one of mysticism and esotericism, so is the nature of the guru. As Shri Ram Chandra (Babuji Maharaj) states, “A guru is a mystery that solves another mystery—that of God.”

In a world that is engrossed in satisfying the whims and desires of the physical body, it is easy to see why this spiritual journey to the inner self is not popular with the general public. And for the few who might have a casual interest in the matter, choosing a guru might be unpleasant to the ego. Dr. Georg Feuerstein, a German-American Indologist, echoes this sentiment in the following statement: “The traditional role of the guru, or spiritual teacher, is not widely understood in the West, even by those professing to practice yoga or some other Eastern tradition entailing discipleship. . . . Spiritual teachers, by their very nature, swim against the stream of conventional values and pursuits. They are not interested in acquiring and accumulating material wealth or in competing in the marketplace, or in pleasing egos. They are not even about morality. Typically, their message is of a radical nature, asking that we live consciously, inspect our motives, transcend our egoist passions, overcome our intellectual blindness, live peacefully with our fellow humans, and, finally, realize the deepest core of human nature, the Spirit. For those wishing to devote their time and energy to the pursuit of conventional life, this kind of message is revolutionary, subversive, and profoundly disturbing.”

As with all things in life, there are organizations and people who are sincere and those who are fraudulent. The same holds true for spiritual organizations and spiritual teachers. In some countries, such as India, the guru-disciple tradition is an integral part of the culture. There have, however, been self-proclaimed gurus and spiritual organizations that have duped and defrauded the naive and misguided spiritual aspirant. This has made the general public wary of joining any spiritual organization. This has done great harm to the sincere spiritual movements. The interested spiritual aspirant is encouraged to take great care in making decisions regarding joining a spiritual organization or choosing a guru.

APPLICATION OF YOGA

Perverted, negative, and excessive use of sense objects, time, and the power of discrimination is the threefold cause of both psychic and somatic disorders. Both body and mind are the locations of disorders as well as pleasure. [The inner self] is devoid of disorders; it is the cause of consciousness in conjunction with the mind, and the five elements (the senses—sound, touch, appearance, flavor, odor) and the sense organs (hearing, feeling, seeing, tasting, smelling); it is eternal—the seer who sees all the actions.

It is important for holistic practitioners to have an understanding of the fundamental aspects of yogic philosophy. When yogic philosophies and practices are understood, CAM practitioners can find ways to incorporate them into Western medicine. These philosophies have already been incorporated into Ayurvedic medicine. In fact, they are a large part of Ayurvedic practice. Ayurvedic medicine’s goals are also said to be aligned with the goals of yoga. Ayurveda suggests that overindulgence of the senses is implicated in certain disease processes, and yoga offers a way to curtail the indulgence of the senses. In Western medicine, spiritual practices such as meditation are recommended for the health benefits that they provide. Ayurvedic medicine also attests to this, but in Ayurveda the focus is on keeping the body healthy to pursue spiritual goals. Yogic philosophy views the body as a vehicle for the soul in the journey toward enlightenment. In yogic philosophy, meditation is not practiced to improve the health of the physical body; rather, health is maintained so that one can meditate and make progress on the spiritual journey. This is a radically different paradigm from that of Western medicine.

In the Western medical climate, our patients suffer from many chronic conditions such as depression and back pain. Traditional Western medicine has not found sustainable long-term cures for many of these chronic conditions. The role that CAM and holistic practitioners play in finding solutions to these chronic problems is an important one, and vital to the health of the public. Yogic philosophies and practices can become an important tool used to bring solutions for these chronic conditions. The fundamental yogic belief that all human suffering stems from the individual’s unawareness of his or her inner divinity is a powerful paradigm shift to be introduced into modern medicine. This would radically alter our approach to treatment of chronic maladies such as depression, anxiety, fibromyalgia, and chronic pain syndromes.

There is little rigorous research on the use of yoga to treat various conditions; however, there is an abundance of anecdotal information on the benefits of yoga. Yoga teachers and practitioners claim that yoga relieves stress; enhances physical strength, stamina, and flexibility; facilitates impulse control; boosts immune function; improves blood circulation; increases memory and concentration; enables positive thinking; and bestows peace of mind. There are claims that yoga provides therapeutic relief for many ailments, including heartburn, asthma, arthritis, anxiety, depression, and hypertension. Research into the field of yoga is slowly gaining momentum; however, there are no studies focusing on the deeper spiritual aspects of yoga. It is this field of knowledge that could greatly influence modern medicine.

At the core of yogic practice is meditation. Yogic literature offers many techniques to enable effective meditation. The effects of meditation have been studied, and meditation has been proven to have many benefits, including reduction in stress and blood pressure. Modern medicine is making great discoveries regarding the benefits of meditation, but little research is being done on the relative effectiveness of different meditative practices. This is one area in which the field of yoga could be naturally integrated into modern medicine. Yoga offers various meditative techniques, but more importantly it has an abundant store of knowledge on ways to curtail distractions during meditation. Given that meditation has a positive effect, it becomes important for the holistic practitioner to learn the ways and means to enable deep meditative states. This is perhaps one of the most important contributions yoga can make to modern medicine.

The application of yogic principles to the fields of preventive medicine and whole person wellness is another area in which modern Western medicine might garner great benefit. Yogic philosophy recommends that the practice of yoga be incorporated into one’s existence as a way of life. Yogic literature claims that the dedicated practice of yoga leads to a cleansing of the subtle energy channels. These energy channels are said to course through all organs and parts of the body. This leads to a purification of the body and enables proper functioning of the organs. Further research is needed to validate these claims and to ascertain any benefit at the physical level. The dedicated practice of yoga is also said to lead to the condition in which the individual is grounded in the true inner self and is not afflicted by the transient phenomenal world. In our present culture, a large percentage of patients have mental disorders such as depression, anxiety, and a variety of psychosomatic conditions. When patients are taught methods that allow them to regulate their minds to understand their spiritual selves, they will develop the mental equipoise that can keep such mental disorders at bay. If the practice of yoga is started before individuals develop psychiatric disorders, it might work as prophylaxis against such disorders. Yogic literature recommends living in balance with nature. It also provides means for the individual’s faculties of body, mind, and spirit to exist in union with nature, which could lead to an increased sense of whole person wellness.

The application of yoga in modern Western medicine involves many radical paradigm shifts. This should not discourage the scientific community from pursuing a deeper understanding of yogic knowledge in order to apply it to modern medical practice. Yogic theories, at a minimum, reinforce the belief that the human is a physical, mental, and spiritual being. Yoga also supports theories of bioenergies with its detailed explanation of the various subtle energy channels in the astral body. At a simple level, it offers methods for achieving physical and mental well-being. At a deeper level, it offers methods for enlivening the inner spirit. However, yogic literature declares that higher spiritual states cannot be measured, they can only be experienced. Modern medicine, along with the mind-body-spirit movement in CAM fields, has made great strides in understanding the spirit and applying it to health, but the “unknown” aspects of this spiritual science have not been explored. The unmeasurableness of the unknown is perhaps one of the reasons that these mystical aspects have not been explored in depth. Modern science is dedicated to providing measurable and tangible results, but this is not possible for the deep mystical aspects of yoga. This arena is beyond the region of the intellect and can only be experienced by intuition. The surrogate markers of cortisol levels and brain waves do not tell the whole story. Relying on such measures is like trying to appreciate a Picasso painting by looking at a chart that details the percentage of each color used in the painting. To harvest the higher fruits of yoga for application in modern medicine will require the concerted, dedicated, and creative efforts of the professionals involved in CAM research. This will make possible a higher level of wellness and improved well-being for the individual and for society in general.

THE HEART OF THE MATTER

Beyond the senses are the objects; beyond the objects is the mind; beyond the mind, the intellect; beyond the intellect, the Great Atman; beyond the Great Atman, the Unmanifest; beyond the Unmanifest, the Purusha. Beyond the Purusha there is nothing: this is the end, the Supreme Goal.

In a world culture that promotes the indulgence of our senses and the cultivation of our ego, it is easy to understand why this journey to the inner self is not so popular. Our societies are defined by the flavors of cuisine, fashions of dress, and styles of music and various other instruments designed to satisfy the senses. Our cultures judge individuals based on wealth, professions, power, social status, and a myriad of other mechanisms designed to keep the individual’s ego attached to the material world. It would appear that the world as the manifest universe exists to keep humans occupied so that they ignore the inner self. However, yogic literature declares that the world exists to provide experiences for the individual so that the individual’s higher consciousness may unfold. This journey from the association with the outside world to the inner divinity is long and fraught with many obstacles. At a minimum, the individual should have an earnest desire to undergo the journey. Although only a small percentage of people fit into this category, yogic literature holds that the desire for knowledge of self exists in all individuals, although it is a latent phenomenon in most.

Yoga in essence is concerned with the expansion of human awareness or consciousness until it is merged with Divine Consciousness. Although the journey toward this expanded consciousness involves concepts of renunciation, this should not be interpreted to mean escapism or austerity. The human being exists as a part of the manifest universe, and the “awakened” individual is meant to live and function in the material world. When the individual experiences an expansion of consciousness, the person is meant to use this for the betterment of his or her surroundings. As a sentient being who is part of the manifest universe, the individual has a responsibility to care for the manifest universe. This responsibility includes existing in a state of balance with nature, and extends to assisting one’s fellow humans on the spiritual journey. The expanded awareness is not meant to be an escapism that occurs during meditation, but a general state of being that stays with the individual while the individual is performing his or her duties in the world.

Yoga is a complex science that has evolved over thousands of years. As yoga has evolved through the ages, many different movements and branches have been established. Some have attempted to simplify the methods to suit modern times. The innumerable organizations have adopted different methods and different goals. Some have abandoned the goal of merging with the Divine Consciousness and have chosen instead to focus on techniques to promote physical fitness and mental relaxation. The serious spiritual aspirant is encouraged to consider the true goal of yoga when choosing a path. Yogic literature repeatedly states the importance of having a capable spiritual master to gain knowledge of the deeper spiritual aspects of yoga. Regardless of the path chosen, Yoga is a lifelong dedicated practice, and the aspirant should be wary of any weekend courses that promise profound changes. The benefits of yoga are commensurate with the dedication, sincerity, and discipline that the spiritual aspirant brings to the practice.

Acknowledgments

All gratitude to Puyja Shri Parthasarathi Rajagopalachari, for all that he has given and for all that he is waiting to give.

Chapter References can be found on the Evolve website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Micozzi/complementary/

Chapter References can be found on the Evolve website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Micozzi/complementary/