5

THE DAY OF VENUS

PHILOLOGUS LOOKED DOWN into his clay cup. It held only water, without even the slightest bit of wine to give it flavor. He could remember his last thought before falling asleep the night before. He and his family had successfully dodged death for one more day. And now a new day was beginning. But how long could anyone postpone starvation and death? How long could a man go on living in fear of everything from crazy emperors to crumbling buildings? Philologus had been a plasterer, and he knew how many cracks in the buildings should have been repaired but were only plastered over. He knew how dangerous it was just to walk down the narrow streets or stand between two buildings.

“I hate plain water.” The frustration of unemployment was coming out in complaints about the smallest things.

Julia looked at him disapprovingly. She kept looking at him, seated there on the bench at their small wooden table, but she spoke to her children. “Children, what your father is doing right now is called complaining. Rather than being thankful that he has water, he is grumbling because he has no wine.”

Philologus sighed. “It seems like we just had a fasting day two days ago.”

“We did, beloved. But today is a fasting day, too. Which is convenient for us, since we have no money for lunch anyway. So you see, the Lord has blessed us.”

Philologus looked at Julia. She was smirking. She was not that naive, after all, but her comment did sting, since he took it as his responsibility to provide for his family. Although it was day two of the games today, there would be no circus for Philologus. He had to find work.

Stachys was shown to the front of the line of clients in Urbanus’s atrium, and Urbanus got right down to business. “I have another audience with the emperor today.”

“Do you think he will name you as prefect?”

“I believe he will. But if he does, Geta will be more envious than ever. And if he does not, I’ll be dishonored, and Geta is still a threat. But I have a plan. I need you to meet me tonight, at the sixteenth hour. The warehouses at the foot of the Aventine, by the river. Don’t be late.”

At that same moment Lucius Geta paced in his anteroom. A Praetorian rushed in and startled him.

“My lord Geta.”

“Yes, what is it?”

“It’s your wife. She has begun the first pains of delivery. May Mars give you a son!”

“Ah. A son, indeed. By Priapus, I had to expose three girls to get my boy—another would be good. Take a message to her.” The soldier reached into a leather messenger bag and pulled out a wax tablet set in a double wooden frame. He took out a stylus and stood at attention, waiting to take dictation. Geta thought about what to say. “To my wife. I hear you are about to deliver the child. May Janus protect you. I regret that business prevents me from being present at the child’s birth. If it is a boy, keep it. Your husband.”

The soldier closed the frame and put the tablet and stylus into his bag. Geta frowned. “She’s not going to like my decision. But there you have it. Now take it to her.” The soldier saluted and turned to leave.

“Wait.” The soldier turned back toward Geta. “Don’t write this down, but give a message to the midwife, so that my wife doesn’t hear it.”

“Yes, lord.”

“If it’s a girl, it’s to be drowned. Not exposed. I don’t want it picked up by a pimp and raised in a brothel. Now go.”

“Yes, lord.” And with that, the soldier was gone, and Geta resumed his pacing.

When Stachys told Maria he would be going out after the evening meeting, she seemed visibly shaken. “You’re going out at night? After we lock the doors?”

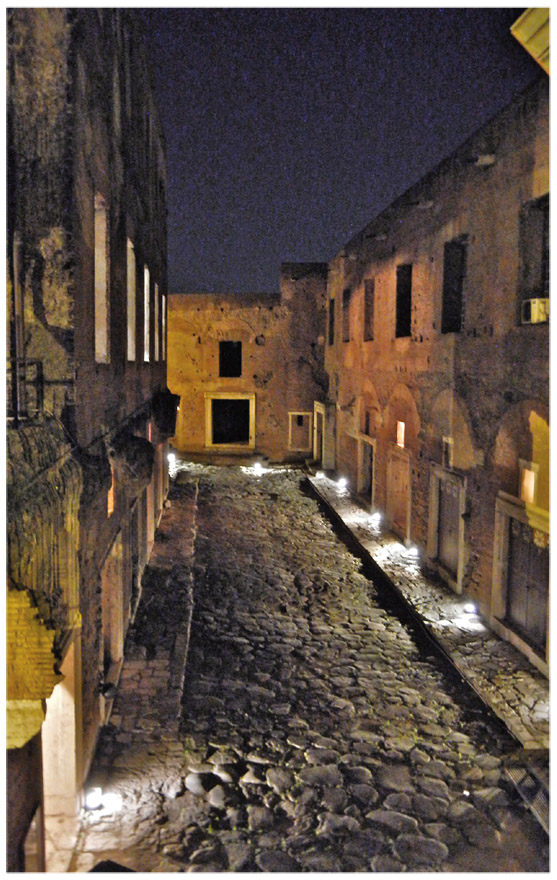

Night in Rome

It’s hard for those of us who live in populated areas to imagine just how dark it would have been at night in the ancient world. Without streetlights, or even the ambient light of a city’s skyline, there was only the moon. On top of that, there was very little of what we would call police presence at night in the city of Rome. Although there were squads of night watchmen who walked the streets, a person had to be caught in the act of committing a crime in order to be prosecuted—which made criminals quite bold at night. In fact, even the murder of a noncitizen would never have been investigated. So nighttime was considered the realm of robbers, muggers, and killers, who knew that there was no system in place to investigate crimes after the fact.

Figure 5.1. A Roman street with shops at night, Markets of Trajan, Rome

On the other hand, nighttime was when all the transportation of goods took place in Rome. By law, no cart traffic was allowed within the city wall during the day, with the exception of some construction carts and anything under the authority of the Vestal Virgins. So everything had to be moved at night. Porters, cart drivers, and construction workers shouted and swore as carts pounded and scraped the paving stones of the major roads, and the fire brigades ran to and from the nightly apartment fires around the city.

Therefore, although it was very dark at night, it was also very noisy. Nevertheless, going out at night was considered a dangerous enterprise. Most people stayed inside behind locked doors after dark, and those who were out at a banquet or other social gathering until after dark would normally plan to have slaves waiting for them with torches to light the way and to serve as bodyguards.

“I don’t have a choice. My patron requested me. What can I do?”

“Well, we know you can’t say no to him,” she said with contempt.

“That’s not fair.”

“You’re going to talk to me about fair?” Maria paused, then sighed. “Listen, it’s dangerous out there at night. And there’s no moon tonight, so it’s going to be completely dark. You’ll need to take a torch. You’re not going alone, are you?”

“I have to.”

Marcus said goodbye to the people who were leaving the morning prayer gathering. Then he turned to those who had stayed. “All right, now. Time for school. Let’s sit over here. Stachys, come on, we’re having school.”

Stachys sighed. Although he had decided to postpone his baptism, he couldn’t come up with an excuse to get out of the school meeting, and he certainly didn’t want to get into a discussion about his decision with Marcus. So he walked over to the group without saying anything, determined to sit in the back and stay quiet.

Marcus faced the catechumens. “We’ve been talking about the expectations of a baptized Way-follower, because, well, you have to know what you’re committing to. You know that the lifestyle of a Way-follower is very different from what most people are used to—and what most people would expect of a patriotic Roman. I think that’s why we’re called Way-followers—we follow a different way and live a different lifestyle. There are so many things that the Romans do, and even consider good, that we are not allowed to do. And we’ve already talked about a lot of them. But today I want to tell you that they all come from one place, or they all stem from one source: idolatry. The worship of false gods is the root of all of the sins of the Romans. And believe me, I understand, the Roman gods can be very attractive. Say the right words, and they promise you will have control over your friends and enemies, and lovers will flock to you. The problem with that is, they can’t keep their promises because they’re just made of painted wood, or stone. They don’t exist. But if you believe that they do, well, if you believe that one lie, you’ll believe them all. You’ll believe that sex and gossip and humiliation and death are all forms of entertainment. If you worship creation rather than the Creator, it’s a short step to worshiping yourself.”

Roman Virtues

The classic Roman virtues, which come from Stoic philosophy, were wisdom, courage, self-control, and justice. These may sound like they could be compatible with Christian morals, but the Roman virtues were conceived only with the upper classes in mind and were understood in such a way that they served the needs of the powerful. In other words, Roman virtues had no thought about helping those less fortunate; they were really intended to equip those with authority to make rational decisions that would benefit them in the long run. So while a Christian is expected to practice self-control, the motivation is so that we do not sin against God and others and so that we don’t take advantage of others. The Roman virtue of self-control was motivated by a utilitarian self-interest: I should discipline myself now so that I will benefit later (not so that others will benefit from my discipline).

Another difference between Roman virtues and Christian morals is seen in the difference between Roman philanthropy and Christian charity. Roman philanthropy consisted of the tradition of making donations to the city of Rome, often in the form of building monuments or sponsoring games and shows—but all in the interest of increasing the fame and honor of the donor. Christian charity, on the other hand, was based on the conviction that all people are created in the image of God and are therefore created equal—a belief that the Romans would have thought ridiculous. To read more about the contrast and conflict between early Christian morality and the ethics of the Romans, see my book How Christianity Saved Civilization: And Must Do So Again, cowritten with Mike Aquilina (Sophia Institute Press, 2019).

As Stachys sat in the school meeting listening to Marcus criticize every Roman value he had ever been taught, Urbanus went again to the Palatine Hill to meet with the emperor. This time Claudius was not in the throne room. He was in a smaller audience room, reclining on a brass couch with a down mattress and pillows. Urbanus noted that he was being invited farther into the residential area of the palace than last time, and that must be a good omen. He looked with admiration at the elaborately painted walls, with faux architectural elements, garlands, wreaths, and great scenes of banquets and picnics from floor to ceiling.

Figure 5.2. Painted wall from a Roman villa (National Roman Museum at Palazzo Massimo, Rome)

Figure 5.3. Painted walls from a Roman villa (National Roman Museum at Palazzo Massimo, Rome)

“Hail, son and father of gods . . .”

“Yes, yes,” Claudius interrupted. He paused, then grimaced, holding his stomach. Then he leaned to one side and broke wind loudly. The food tasters rolled their eyes, and a few of the attendants tried their best to stifle their giggles. Agrippina was visibly embarrassed, and Narcissus looked impatient. Claudius seemed annoyed at the various reactions. He shouted at Narcissus, even though Narcissus was close by.

“Narcissus!”

“Yes, lord?”

“Take dictation!”

Narcissus called for a wax tablet and stylus. “Ready, lord.”

“To my co-consul, Antistius Vetus, and the senate. Brother senators, since it is unhealthy and most grievous to the internal organs to suppress the wind which comes from the natural processes of digestion, I propose and advise the Senate to affirm that it is a natural, and most acceptable thing, for a Roman man to fart at will, an act which should in no way draw attention to itself, nor result in ridicule, derision, or revulsion. Signed and sealed, et cetera et cetera, Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus.”

The emperor turned back to Urbanus. “Narcissus advises me to make you prefect of the grain supply.” There was a long pause. Urbanus didn’t know whether to express gratitude or desire for the position, but it didn’t matter because he couldn’t put any words together in time for a response. “Well? Do you want the position?”

“Yes, lord. I would be honored to hold that post.”

“Of course you would be honored. That’s obvious. But would I be honored by you holding the post? That’s what I’m trying to figure out. And I want to do it quickly so I can make my sacrifice to Mars and still get to the arena for today’s executions. By Priapus, it seems like the games get more and more boring with every passing year. So . . . what will you do if you are prefect of the grain supply?”

Urbanus thought for a moment. He wasn’t prepared for the emperor’s question. A thought popped into his head, but he immediately dismissed it. He struggled to think of something else to say, but the silence was becoming uncomfortable, and the emperor was becoming visibly annoyed. Then he said it. It surprised him to hear the thought that he had just dismissed coming out of his mouth. But it just came out, and there it was. There was no taking it back. “I met a man named Philologus who can’t feed his family, and when he went for the distribution of bread, they ran out before he got any. I would want to make sure a man like Philologus can feed his family.”

Back at Stachys’s house, the school meeting ended with a prayer, and the catechumens dispersed. Stachys noticed that Maria was packing a picnic lunch. “What’s this?” he asked her.

Maria gave him a look. “Don’t you know what today is?”

“Should I?”

“Tertius’s mother? The anniversary of her death? We’re going to the cemetery. And you’re coming too.”

Stachys sighed. Normally he was grateful that Maria remembered dates. But he was feeling overwhelmed and more than a little distant from his wife. He nodded his agreement.

They walked in silence, with Tertius leading the way, across the Field of Mars. A cohort of new legionary recruits was practicing marching drills on the field to the west of the Theater of Pompey, so they had to walk around the soldiers to the south, then go north along the river to cross over to the Vatican Hill. Tertius was momentarily distracted by a group of mimes doing a skit in the street to advertise their show later that day. Then a funeral procession blocked their path, and they had to wait while the oboe players and professional mourners walked slowly by, the mourners in their mourning robes with their purposely messed-up hair. Eventually they made their way up the hill, to the cemetery at the back of the Circus of Caligula, and came to Urbanus’s family tomb. As a freedman of the household of Urbanus, Stachys and his family were entitled to be buried in the mausoleum.

Figure 5.4. Remains of a Roman mausoleum with urn niches, Ostia Antica

Figure 5.5. Fragment of a wall painting from a mausoleum with urn niches. Notice the spaces for the names of the deceased below where the niches would have been. The names themselves have faded. (National Roman Museum at Palazzo Massimo, Rome)

Stachys lit a lamp, and the three of them ducked their heads and went into the cubicle that held the burial place of his first wife. Stachys had spent a small fortune for the sarcophagus, carved with elaborate scenes of Elysium, with its gardens and grapevines. There were two faces carved into the side: the face of Tertius’s mother and a blank face, waiting for the sculptor to carve the features of Stachys’s own face when he died. Stachys’s heart turned a bit melancholy when he saw it. The death of his first wife had been hard on him, especially with Tertius losing his mother at barely one year old. Stachys thought about the prospect of his own death, and although suicide would preserve his honor, he knew it would break his family’s hearts, and so he knew he could never go through with it. But he remained stoic and showed no emotion.

Maria opened the basket of food and set out lunch on the lid of the sarcophagus.

“Can I do it?” Tertius asked.

Stachys nodded. “Of course. Go ahead.”

Maria poured some wine into a small clay cup. Tertius took the cup and poured the wine down the libation hole in the sarcophagus lid. The three of them ate their lunch without much conversation, except when Tertius begged Stachys to tell stories about his mother. It was always awkward for Stachys to tell stories about his first wife that would please his son without making his new wife uncomfortable. But he had come to appreciate Maria for taking part in the memorial meals. He looked at his son, who seemed so young. Still such a little boy. So young to be given to a tutor. Stachys could feel that his heart was softening, but he steeled his resolve against changing his mind.

Figure 5.6. Libation hole in the lid of a grave marker. On the anniversary of a loved one’s death, people gathered at the burial site for a picnic called a refrigerium, and part of the ritual included pouring some wine into the hole for the deceased. (Capitoline Museum, Rome)

At Urbanus’s home on the hill, Sabina was getting ready for an afternoon at the theater. She relished the process of choosing the brightest colors to wear and the most expensive jewelry. Urbanus was always telling her to tone it down, for fear of the evil eye, but she never listened—in fact, his pleas only made her exercise the freedom of her noble will all the more. She smiled at her ability to disregard her husband’s wishes as her slave put on her gold bracelets. She was of the senate class, after all, and he was only an equestrian. Sabina wondered to herself whether she would have married Urbanus if she had had more time to choose a second husband. Had she settled for him just because the end of the mourning period was coming up, with its two-year remarriage deadline? But the more she thought about it, the better he looked to her in comparison to other men. He was a good man, after all, and a good husband. He provided for her well, but more important, he took good care of her. No, she decided as she rested her sun parasol on her shoulder, she had not settled for him. She had chosen him.

Sabina had invited Maria, Rhoda, Julia, and Prisca to join her at the baths, but they had declined. She thought it was odd that these Way-follower women, who were mostly poor, would spend the money to go to the private women-only baths. Where was the fun in that? But at least she could look forward to their company at the theater. Sabina had used the fact that they declined her invitation to the baths to coerce them into accepting an invitation to the theater. The women had been very reluctant at first but eventually relented and agreed to attend. Sabina smiled to her herself with pride over her small victory. Today promised to be much more entertaining than spending time with the stuffy old senators’ wives.

Philologus noticed that Julia was preparing to go out and worried that she might be planning to spend the last of their money. She assured him that it wasn’t going to cost them anything, but he pressed for details. When she finally admitted where she was going, he shook his head. “You’re going to the theater? I really wish you wouldn’t. You know Marcus says that Way-followers shouldn’t go to the theater. They have the Bacchus dedication, with the live sex show, and then the plays are all about laughing at other people’s misfortunes. That’s not what we do, Julia.”

“We’re going to arrive after the dedication. And the rest is not that bad. Anyway, the noble lady Sabina invited us, and we’re trying to tell her about Iesua.”

“But how can you tell her about Iesua when you’re at the theater? Isn’t that kind of a mixed message? I heard they have a play called Cinyras and Myrrha about father-daughter incest!”

“I don’t know about that play. I think we’re going to see Verae Matronae Romae. I want to find out what kind of schemes Agrippina is up to.”

“It’s not real, Julia, you know that. Whatever they do on stage, it’s not what the real Agrippina is doing. It’s a farce. Do you think the emperor’s wife is really involved in all that intrigue, committing adultery, and murder?”

“Just take care of the children until I get back, my dove. ” And with that Julia was out the door.

The Theater

The Roman theater was a decaying remnant of the Greek theater. Whereas Greek theater had two kinds of plays—tragedy and comedy—Roman theater replaced the comedy with an erotic musical farce known as the pantomime. Tragic plays continued to use masks and followed the tradition of all roles being played by male actors, but the pantomime did away with the masks and included actresses, who were expected to provide a lot of nudity.

Pantomimes often entertained audiences by humiliating real people and famous families. They included elements of slapstick and vaudeville-like song and dance as well as real sex and fighting on stage. By the late first century there were also snuff plays, in which a condemned criminal could be cast in a role that would end in the character’s—and the criminal’s—death on stage.

Greek theaters were usually built into hills, so that the audience sat on the rise of the hill, giving everyone a good view of the stage. However, the Romans, being more advanced architects and builders, did not need to build on a hill but rather built up the theater as a freestanding structure or as part of a larger complex. Like gladiatorial arenas, theaters had separate seating sections for men and women.

Theater season was April to November, taking a break in the colder months since the theaters were open to the sky. Like the games and other shows, plays always began with pagan ritual, and so they not only paid homage to the Greco-Roman gods but also became a kind of participation in idolatrous worship.

The theater was one of the few places where the common people had a voice. In the safety of numbers, a theater audience could shout slogans expressing political dissatisfaction and even boo the emperor. However, that could backfire if the crowd became riotous; the emperor Caligula once massacred an entire theater audience because they protested a tax increase.

Early Christian writings tried (often in vain) to get Christians to stop going to the plays and other spectacles, since the humiliation, fighting, and public executions only served to add to the cheapening of human life and dignity. As several early Christian theologians wrote, if Christians are not allowed to do something, then they are also not allowed to watch it.

At the time of our story, there were at least three theaters in Rome. The Theater of Balbus was near the Circus Flaminius on the south side of the Field of Mars. The Theater of Pompey was part of a large complex in the center of the Field of Mars. The Theater of Marcellus was near where the city wall met the River Tiber. This latter theater was later the model for the Colosseum.

Figure 5.7. Remains of a Roman theater, Ostia Antica

The women all met at the entrance to the Theater of Balbus, next to the Circus Flaminius. They went in and sat in the women’s section, as close to the stage as they could and still have enough room to sit together. The play was beginning, and Sabina spoke to the group in a whisper. She was playing the hostess, talking to them as if they’d never been to the theater before. Rhoda rolled her eyes a bit but didn’t say anything. The rest of the women were polite and listened.

“I know it might be hard to keep up with the story,” Sabina said. “This is one of Secundus’s most famous tragedies. Just remember that the men in white masks are playing the roles of the women, and the men in the brown masks are playing the roles of the men. The white costume means that one is supposed to be an old man, and the colorful costume means that one is supposed to be a young man. Yellow costume means a courtesan, short tunic means a slave. Um . . . purple costume is a rich person, red costume means a poor person. You’ll get it as the play goes on.”

The women followed the play well enough to be a little embarrassed by a few scenes. When it was over, they stood up and turned toward Sabina. “Now it’s time for a pantomime,” Sabina said.

“I want to see Verae Matronae Romae,” Julia said excitedly.

“Are you sure?” Sabina said. “They’re doing Catullus’s Laureolus at the Theater of Marcellus.”

Maria grimaced. “Oh . . . Catullus . . . I don’t think that’s a good one for us.”

“All right, then,” Sabina said with a smile. “Verae Matronae it is.”

The women made their way to the Theater of Pompey, where the pantomime was already underway. A woman who was playing the part of Claudius’s late third wife, Messalina, was dirty-dancing with a man playing the role of Silius, her lover, while another man playing the role of Claudius was limping and stumbling around the stage, seemingly oblivious to what was going on. The audience howled at Claudius’s pratfalls and shouted, “Take it all off!” as Messalina and Silius groped each other. The woman playing Messalina was wearing a royal toga and crown, and was producing gift after gift out of the folds of the toga as the audience laughed. Finally she produced a long sword and started tiptoeing toward an unsuspecting Claudius. But a group of men playing Praetorian guards came from behind the scenery and mimed killing Silius, at which point Messalina turned the sword on herself and played out an extremely elongated death scene, to the cheers of the crowd. Everyone on stage then broke into a song. Sabina seemed to know the lyrics, but the other women could only make out the refrain:

Life is brutal, but at least it’s short.

Maria wondered at the kind of life one would have to lead to have the free time to be able to learn the songs of the theater shows by heart.

“She didn’t really kill herself,” Sabina said to the other women. Maria was starting to feel as though they shouldn’t be at the show, but the other women wanted to hear what Sabina had to say. “No, she didn’t kill herself. Narcissus had her killed quietly without waiting for Claudius’s permission. And then Claudius promoted him.”

The second act began with another woman, very scantily clad, who was playing the part of Agrippina, Claudius’s new wife. She chased the limping Claudius around the stage, and every time he fell, the audience laughed as she helped him up to resume the chase.

Rhoda leaned toward Sabina. “I heard she’s his niece.”

“That’s right,” Sabina said, waving a feather fan in front of her face. “He forced the senate to change the law forbidding marriage to a niece. But marrying a niece is better than marrying a whore like Messalina.” She passed the fan down the row so the other women could take turns with it and get a break from the heat.

Prisca was shaking her head. “It’s still incest. Nothing good can come of it.”

Julia whispered, “The one I feel sorry for is young Brittanicus. His mother is dead, and now his stepmother has gotten her own son adopted by Claudius. That’s not going to end well.”

Maria frowned. “Ladies, let’s not assume that all stepmothers are evil. Being a stepmother is a tough job. I can only imagine what it’s like if your stepson is a prince.”

Julia and Prisca gave Maria a knowing look of agreement. Sabina said, “Don’t be fooled. The women have the real power. Agrippina rules Rome, make no mistake. She sits on a throne and rides around the city in a chariot, like a general or a priest. The men think they have it all worked out, with the laws in their favor, even giving them complete freedom to kill or have sex with whomever they want. But the women—we have our own forms of power, don’t we? We control the dowries, and we have magic. We have spells and incantations, and if all else fails, we have potions. History may be the story of great men, but they are just marionettes on a stage. It’s the women who hold the strings.”

The other women looked at each other. All eyes landed on Maria. “Sabina,” she said. “About the magic. The spells, the curses, the amulets.” She gestured toward the medallion around Sabina’s neck. “They don’t really work, do they? I mean, you don’t really believe they work?”

“Maybe they don’t, but maybe they do,” Sabina answered. “Anyway it’s worth a try.”

“I don’t think so,” Maria continued. “What I mean is, we believe that those things are, at best, a distraction from the real Deity. And at worst, they could bring evil spirits into your home.”

“Really?” Sabina’s eyes went wide. “You think that could happen?”

“Way-followers believe that putting your trust in magic is a kind of superstition. We put all that away like a girl puts away her dolls when she grows to be a woman. Astrology, too.”

“Alright, now you’ve gone too far,” Sabina scoffed, waving her hand in the air. “What could possibly be wrong with astrology?”

Someone in the crowd shouted, “Hey, Claudius! How about sending the merda carts around to clean up the streets?!” The audience burst into laughter.

Now the chase on the stage turned into a dance, with a steady stream of nude women dancing in from one side, looking at Claudius seductively and then miming their suicides as Agrippina handed them the sword, each in their turn. Then the woman playing Agrippina started stripping in front of Claudius, who mimed being embarrassed. The crowd went back to shouting, “Take it off!” and she didn’t disappoint them. The play ended with the actors having sex on stage, and then a patriotic song, with the whole audience joining in. Julia was starting to look as though she felt sick, and Prisca was blushing and looking down at the floor. Maria and Rhoda realized it was time to leave, so they started getting up and ushered the other women out of the theater, making their goodbyes and thank-yous to Sabina as quickly as possible.

When Julia returned home to her apartment, Philologus and the children were not at home. She wondered where they could be but wasn’t too worried about it until she heard a loud rumbling noise. Her heart skipped a beat. The loud rumbling turned into an even louder crashing, and Julia knew what was happening. A building was collapsing nearby. She couldn’t tell how close it was, so she couldn’t know whether the collapsing building was going to bring her building down with it. So she ran for the stairs.

Outside the noise was deafening. Everywhere people were running out of the buildings and into the street, pushing and shoving their way without even knowing which direction they should go. Julia called for her children. She spun around, looking in every direction, but she could not see them, and she could barely hear her own voice as she screamed their names until her throat was sore. The streets between the buildings were so narrow that not much light could find its way to the ground, and now a cloud of dust was rolling along the street, blocking out what little light there was in a gritty haze. Julia tried to figure out where the collapse was so she could run away from it, but she couldn’t see farther than the length of one building, and she knew that if any of the walls around her fell she would be crushed. She could hear yelling and crying, and she strained her ears to see whether any of the voices belonged to her children.

Julia kept calling out her children’s names even after her voice gave out. She ran to the end of the building and looked around the corner. People seemed to be running in the direction of the Forum of Augustus, so she ran that way too, hoping that her children were also running away from the collapse, praying that she would find them at the forum.

When the dust cleared, and her children were nowhere in sight, Julia ran back toward the collapsed building. She found it, now a pile of rubble, plaster, and wooden beams, and went to help pull the survivors out. All the while she kept scanning her surroundings, looking for her children. She was nearly blinded by her tears as she came upon the broken body of someone else’s child, pulling the small, lifeless form from a heap of plaster and stone. Then she found another, and she was paralyzed. She desperately prayed to the Lord that her children were safe.

Julia worked as long as she could, digging through the rubble and helping to reunite other people’s families. When her hands were raw and bloody, and the sounds of crying had dwindled, and when it was clear that there was no more she could do, Julia walked back to her apartment, hoping to find her husband and children at home. But she was disappointed. The apartment was empty. Not knowing what else to do, she started walking toward Stachys and Maria’s house.

When Maria saw Julia covered in dust and dirt, with bloody hands, she ran to her and grabbed Julia’s arms, looking into her expressionless face. “What happened? Where are the children?”

Julia tried to speak through her tears. “Building collapse. Not our building, another one. But I don’t know where the children are. I was hoping they were here.” Julia started to cry, and Maria pulled her close. Julia’s head dropped onto Maria’s shoulder, and her red ponytail bobbed up and down with her sobs.

“What’s wrong?” It was Philologus coming in, covered in black dirt from head to toe.

Julia heard his voice and ran to him. “Oh, you’re not hurt, are you? Were you buried in the collapse?”

“What collapse?

“An apartment near ours. Do you know where the children are?”

“Of course I do. They’re at Pudens’s house, with his daughters.”

Julia breathed a sigh that immediately turned into crying. Through her sobs she asked, “Where were you? Why weren’t they with you?”

Philologus smiled. “Because I got a job!”

“What?” Julia’s tears were slowing, and her face started to light up.

“Yes, I got a job. It’s dirty work, but the good news is the work won’t be done for a very long time. I’m digging grave tunnels at the quarry. Senator Pudens, he gave me an old pickaxe and told me where they were digging, and I just showed up and signed on. I have a job!”

Marcus smiled. “Congratulations!”

Stachys seemed skeptical. “Wait. If you’re digging grave tunnels, you’ll be a social outcast, no better than a gladiator, a pimp, or an actor!”

Marcus jumped to Philologus’s defense. “Stachys, old man, you’re going to have to get used to the idea that Way-followers are already social outcasts. As long as we reject the traditions of Rome, we’ll never be seen as good Romans.”

“Yes,” Philologus agreed, “and you heard Paul’s letter to the Way-followers at Thessalonica. People are going to fall asleep. Way-followers, who will need a decent burial. Maybe I can help with that. We’re going to need to take care of our dead as they wait for the resurrection. In fact, we could organize our gatherings as funeral clubs. That way everything would be legal.”

Young Clemens joined the conversation. “He may be right. . . . Funeral clubs collect dues, so we can collect money to help take care of the widows and orphans. Funeral clubs allow both men and women, free and slave, and so do we. Funeral clubs have banquets, we have the agapē meal. It’s perfect. Actually, it’s kind of poetic. Our security is in the cemeteries.”

“Well,” Marcus said thoughtfully, “we can’t make a decision on that until Peter arrives. For now, let’s get ready for the gathering.”

In another part of the city, in a butcher’s apartment on Long Street in the valley between the Quirinal Hill and the Viminal Hill, another gathering of Way-followers was beginning their evening meal. The host greeted the group’s leader. “Salve, Aquilinus!”

“Salve, brother. But I’ve told you—everyone calls me Linus.”

“Linus, then. How is your father, old Herculanus?”

“He’s well, thank you for asking.”

“Ah! Ephebus. Linus, you remember Ephebus. He serves in the house of Narcissus. And this is Bito, from the imperial house.”

“Salvete, brothers. Now, everyone! Everyone! Let’s gather for the prayers.”

After the prayers and petitions, Linus opened a scroll and read a story about a man named Daniel. He was thrown to the lions, but the one true God protected him, and the lions only licked his face, like harmless puppies. Then Linus set the scroll aside and said, “This story of Daniel happened a long time ago. But here we are in such an age that congratulates itself for being civilized, and yet people are still thrown to the lions. True, many of them are condemned criminals, but does that mean they cannot be saved? Iesua would say no, they can be saved. Iesua would say it’s not too late for anyone to turn their lives around, turn over a new leaf, and start fresh. Brothers and sisters, I know that you gathered here are not likely to commit the kinds of crimes that would result in your execution. But I want you to consider whether you are participating in murder by going to the spectacles and witnessing, yes, even cheering, for the death of those men who end their lives in the arena. Some of them, their only crime was to be a slave and be unfortunate enough to be sold to the gladiator school. Here in the midst of these three days of games and shows, I believe that we Way-followers should not be attending them—even if we are ridiculed for avoiding the circus, the theater, the arena. Iesua himself said you are blessed when they ridicule you.”

Peter looked up into the heavens and prayed. The small gathering of sailors and passengers lifted their eyes and their hands, and when Peter’s prayer was done, they walked off singing, and the sailors headed back to their work, still singing the hymn. Peter’s eyes scanned the horizon. He thanked his Lord Iesua, the one who was before Abraham was, for the colorful sunset that painted the sparkling water. But he could not see the coastline, and that worried him. He looked forward to reaching Ostia, where the ship would finally drop anchor. Peter thought about another time when he had longed to get to shore and drop anchor. It was the time a storm almost capsized his boat—that is, until Iesua calmed the sea. And now the Way-followers were tossed about on the rough waters of the empire. Peter thought about the anchor. He thought about how it could represent stability in times of tribulation and how it could stand for the peaceful, safe harbor of heaven. The Way-followers would need a symbol to unite them. Maybe the anchor could be such a symbol—standing for the stability of the faith and the hope of peace in eternity. Peter smiled. He could not think of a better symbol to represent the Way-followers and their good news.

The city was dark as a tomb but just as loud as if it were daytime. Stachys walked with his torch, dodging the carts and wagons, trying to stay out of sight of the night watchmen. The carts made an ear-splitting scraping sound as their iron-rimmed front wheels skidded on the paving stones to turn the corners. Mule drivers shouted at each other as the carts maneuvered past one another on the narrow roads. Porters unloaded their cargos, and the bakers began their nightly work. A large, loud group of people coming from a banquet sang their way down the street, surrounded by bodyguards with torches. Someone yelled about a cart wheel running over his foot. Stachys was startled when a group of people started banging pots and pans together to call the moon back to share its light.

Eventually Stachys found Urbanus by the warehouses. He started to say something to Urbanus, but Urbanus pulled him into an open warehouse stall and put his hand over Stachys’s mouth. Urbanus crouched down and motioned for Stachys to do the same. There they waited.

Finally, Stachys whispered, “What are we waiting for?”

“You’ll see. Now be quiet.”

“Hades! It never fails. Always at the worst time, I have to go to the forica.”

Figure 5.8. The Roman forica was the public latrine, which was equipped with a running water flush system. Since most people did not have bathrooms (beyond the chamber pot) in their homes, everyone expected to use the public facilities regularly.

Urbanus rolled his eyes. “Just hold it.”

After a silence, Stachys whispered, “Urbanus, do you believe that there is one high god over all the other gods? “I don’t know. Some of the philosophers teach that there is. I suppose it makes more sense than all that rigmarole on the top of Mount Olympus. But how would I know?”

“The Way-followers believe in only one God. But it’s not just a high god over the other gods. It’s only one God. And the truly strange thing is, they say this God loves us. Isn’t that weird? I know what love is between a man and his lover. But between a god and a man? They say this God cares what happens to us. Can you believe that? They say this God cares what happens to us, and then when we die, we go to paradise to be with this God.”

“If that were true, then why don’t they just kill themselves so they can get there sooner?”

Stachys stuck out his bottom lip. “That’s a good question. I’ll have to ask Marcus. They don’t fear death, but they don’t seek it either. And if one of them dies, the others are sad.”

“The philosophers say that when you die, you come back and start all over again. That’s probably what happens.”

“You think?”

“Yeah. Trouble is, you can’t remember the previous life, so you really do have to start over. You figure it out, or you don’t. I guess the high god cares what you do, in the sense that he wants you to figure it out. But he doesn’t go out of his way to help you. Then again, if Plato was right, why did they make Socrates kill himself? . . . Now, be quiet and wait. Soon you will be avenged for being mistreated. I want you to see this with your own eyes.”

After a while they heard the brass nails of military boots coming along on the paving stones. Stachys was afraid it was one of the night watchmen. Urbanus made a sign for Stachys to be quiet. Then someone in the uniform of the Praetorians walked by the stall where Urbanus and Stachys were hiding. As he walked on, five gladiators stepped out from one of the other stalls and blocked his way. Stachys was shocked to see that the Praetorian was Geta, and then even more shocked when the group of gladiators started beating him with their fists and with clubs.

Urbanus defended his actions. “I hired the gladiators. Just to send the message to Geta that he can’t threaten my freedman. I had to do something to answer the affront to my honor.”

The gladiators finished their beating and ran off, leaving Geta lying motionless in the street. Urbanus waited for a short time, then stood up and slowly approached. Stachys followed but stayed behind Urbanus. Urbanus kicked Geta. “Va cacá!”

“What?”

“He’s dead.”

“No! Are you sure?”

“Yeah. I’m sure. Hades! They weren’t supposed to kill him.”

“What do we do?”

“Grab his legs.”

“What?!”

“Get his legs. We have to get rid of the body before the night watchmen come along. You have to help me.”

Stachys took Geta’s legs, and Urbanus took his arms, and they dragged his body to the Tiber and rolled it into the churning water.