7

THE DAY OF THE SUN

BEFORE THE GLADIATOR COULD draw his sword, a large hand slapped down onto his wrist and gripped it tightly. The gladiator winced in pain as the meaty hand squeezed. The hand had a tattoo on it—four letters across the four fingers of the fist: S. P. Q. R. It was the hand of a centurion.

The centurion said, “These aren’t the ones you’re looking for. Now move along, barleymen.”

The gladiators looked at the centurion. Then they looked at the squad of soldiers behind him. Then they took their hands off their swords and walked away.

The centurion walked up to Peter. He stared at Peter, then he smiled.

Peter smiled and said, “Cornelius!” The two men gave each other a bear hug and kissed each other’s cheeks. “Cornelius, my friend, I didn’t know you were in Rome!”

“I just dropped anchor. Pudens said there might be trouble. Allow me to escort you.”

Peter looked at Cornelius’s hands. “I see the legionary tattoo. But what’s that on your other hand? V. P. M. S. What does that stand for?”

Cornelius smiled. “It stands for Vade Post Me Satana.”

Peter shook his head. “‘Get behind me, Satan.’ Thanks for the reminder of Iesua’s rebuke.”

“Relax, Peter,” Cornelius said, as he started walking in the direction of Pudens’s house. “It’s not personal. It wasn’t really about you then, and it’s not about you now. Just a little reminder to myself that the real battle is not against flesh and blood. But I’m impressed you were able to translate that so quickly. Your Latin is pretty good.”

“Ever since Pentecost.”

The morning prayer gathering at Pudens’s house was buzzing with excitement, and it was difficult to keep everyone quiet. Many Way-followers from the other gatherings had come to Pudens’s house, and the presence of both Peter and Cornelius was making it hard to get everyone to settle down.

Peter finally got their attention and said, “Everyone, I want to introduce you to a friend of ours, Cornelius. He is one of the first non-Judeans to become a believer, so he knows what it’s like for most of you, who have been grafted onto the family tree, so to speak. Cornelius, this is Anacletus. He’s our leader this morning.”

Cletus shook Cornelius’s hand. “Call me Cletus. Peter, are you sure you don’t want to lead?”

“No, just pretend I’m not here.”

Cletus smiled. “I’m sure that’s not possible.”

After the prayer meeting, the shepherds of all four gatherings met with Peter, along with the other leaders of the Way-followers in Rome. Marcus, Linus, Cletus, and Apelles were there, as were the deacons Philologus, Ampliatus, and young Clemens, as well as Julia and Prisca. Peter gathered them close. Scrap hid behind a curtain to hear what Peter was saying.

“Brothers and sisters, it’s good to be back in Rome. Thank you for watching over the flock while I was away. I bring good news from Jerusalem and the other apostles.”

Evangelization and

Conversion in the Early Church

The early church was not a “seeker sensitive” kind of experience. Especially during times of persecution, early Christians might have been suspicious of anyone who walked in off the street claiming to want to join. In fact, it’s hard to imagine anyone asking to join the church without first knowing church members intimately.

Conversion in the early church was through relationships. We have to remember that in the Greco-Roman world, people didn’t generally think of themselves as individuals the way we do today. And for those of us who live in the United States, with concepts such as personal freedom, human rights, and the possibility that one person can “make a difference” in the world, it may be hard for us to understand that none of those things would have seemed possible for anyone but the “one percent.” The Roman personality was formed as part of a group, and so a Roman person’s identity was not as an individual but as a member of a group—usually a family, but then also as a part of other connections, including patron-client networks, trade guilds, sports-team factions, and, yes, religious cults. This means that conversion into a religious movement was generally not an individual decision—or if it was the decision of the head of a household, it affected the whole household.

Add to this the fact that for Christianity, a decision to join also meant a commitment to abandon all Greco-Roman religious loyalties, and we can see that almost no one would have joined the church without bringing a support system along. This means that in the early years of Christianity, most of the conversions were conversions of families, who were then drawn into the larger family of the church. The church became their new extended family—often replacing the actual extended family that may have ostracized them.

For more information on the growth of Christianity in the early centuries, read the works of Rodney Stark, especially The Rise of Christianity (Princeton University Press, 1996) and Cities of God (HarperOne, 2007).

“Only good news?” Philologus seemed worried.

“Yes, Philologus, only good news. Why? Does my arrival come with a dark cloud?” And then the smile left Peter’s face as he remembered the first time he arrived in Rome, coming with the news of the death of James. “Oh, right. Well, thank the Lord, nothing like that. Now I know you’ve heard about the council, but there’s something I didn’t say in my letter. I wanted to tell you in person.”

The group was silent, ears at attention.

“We have agreed that from now on we are to call ourselves . . . Christians.”

Everyone spoke at once. “Not Way-followers?” “What does it mean?” “What is a Christian?”

Prisca said, “I understand. Christians. Because we are followers, not only of the way of the Lord, but we are followers of the Lord himself. He is the way. Christian means followers of the Christos.”

“Yes, but it means more than that,” Peter said excitedly. “Remember that Christos means ‘one who is anointed.’ So just as Iesua is the Anointed One, the Messiah, we as Christians are also anointed by God and adopted as God’s sons and daughters.”

More chatter from the group. “Christians.” “We’re Christians.”

Peter continued, “We now have four thriving gatherings in Rome, each with over fifteen baptized believers at the table. And someday, when Judeans are allowed to come back to Rome, the gathering at Prisca’s shop will make five. And we’re growing. That means it’s no longer going to be practical for the deacons to be runners, taking the Thanksgiving Bread from one gathering to the rest. So I’m giving all of the shepherds—Marcus, Linus, Cletus, and Apelles—the authority to preside over the prayers that consecrate the Thanksgiving Bread. So then each gathering will have its own presider, who will function as the paterfamilias of that group of Christians. He will watch over his flock, and he will say the prayers over the bread and wine. The deacons—Philologus, young Clemens, Ampliatus—you men will assist in the serving. You will still take the Thanksgiving Bread out to any who are sick or who cannot be at the gathering, and you will care for the sick and let the shepherds know who is in need. And if a woman is sick, and there is no man in her house to chaperone, then the women will go out and care for her. Susannah will be a guide for the women, and I need you ladies also to keep your ears open to any who might be in need and let the shepherds know. If our Lord brings to our attention anyone who is sick or starving—if we can help them, we should. Even if they’re not Christians. And if any of our number should die, Philologus will be in charge of the burials.”

Marcus spoke up. “But you will be here, too, Peter. Right?”

“I will, Marcus,” Peter answered. “I’ll stay in Rome as long as I can, and I’ll share the ministry in Pudens’s house, since his gathering is the largest.” Peter paused in thought for a moment. “I remember one of the last conversations I had with our Lord. He asked me whether I loved him. And then he told me to take care of his sheep. So, just as Iesua is the Good Shepherd over us all, the flock of each gathering of the church needs a shepherd. Just as God is our Father, each gathering needs a housefather. We need this structure for several reasons. We need it so that every baptized believer will have access to the sacred mystery of the Thanksgiving Bread. And we need it so that we can make sure that the teachings Iesua gave us are faithfully and truthfully handed down from one generation to the next. And finally, we need it so that we will be able to take care of those who are sick or hungry or imprisoned.”

Marcus asked, “Is Paul coming to Rome?”

“Not anytime soon,” Peter answered. “He’s concentrating on going to places where there are no Christians yet, where people don’t know about Iesua. And, to his credit, he said he didn’t want to step on my toes by coming to Rome and trying to build on the foundation I’ve laid. He’ll come eventually, I’m sure. He wants to go to Spain, so he’s going to have to come through Rome at some point.”

When the meeting broke up, Peter took Stachys aside. He put his hand on Stachys’s shoulder and gripped it as he looked Stachys in the eyes. “Stachys, I’ll get right to the point. We’re going to need another deacon. Marcus says you’re ready for baptism, so are you up for it?”

Stachys was stunned for a moment. “I’m sorry, Peter.” Stachys shook his head. “Marcus has no idea. He means well, but I am not ready for baptism. You don’t know what I’ve been through.”

“I heard a little about it. But it sounds like you’ve turned a corner with your faith. From what I hear, it sounds like you’re ready to make the commitment to live as a Christian.”

Stachys couldn’t look Peter in the eye. “It’s not that. I can make that commitment now. But you don’t know . . . what I did. What I said.”

“Sit down here.” Peter gestured toward a bench. Stachys sat down on the bench, and Peter sat next to him. Stachys thought that Peter was sitting a little too close for comfort. Peter leaned in toward Stachys and whispered, “Tell me.”

Stachys didn’t feel ready to talk about it. But deep down he knew he needed to tell someone. “The first time . . . when they asked if I was a Way-follower . . . I said no. I denied being part of the family, so how can I ask to be initiated to the family’s table?”

Peter smiled. “Oh, Stachys. You couldn’t know this, but I once asked the same question.” Peter’s tone of voice changed as his eyes suddenly became red and watery. “Even though I walked with him on the water . . . briefly. Even though I had all the proof I should need for my faith to be solid as a rock, I still denied him. Not once but three times. At the very time when Iesua needed friends the most, I said I was not his friend. Stachys, I know what it’s like to be afraid. And I know what it’s like to act out of fear and say and do things that later made me ashamed and horrified to think that it was I who did and said those things. But Iesua forgave me. He had compassion on my weakness. And look at me now, sailing all over the empire as his ambassador. If I can be an apostle, surely you can be a deacon.”

“But do you really want me? There must be others more qualified.”

“Stachys, sometimes the ones who needed the most forgiveness are the ones who are the most grateful and become the most enthusiastic ambassadors of our Lord. And I’ll tell you something else. Before his ascension he gave me and the other apostles the authority to forgive sins in his name—to go and find his lost lambs and bring them back to the flock. So in the name of Iesua, I release you from your sin, freeing you to serve him. And I seal you with the sign of his passion, the once-and-for-all sacrifice for the forgiveness of all who claim him as their Lord.” Peter used his thumb to trace a small cross on Stachys’s forehead. “And as soon as you are baptized, you will be one of the deacons of the church at Rome.”

In the afternoon, all of the Christians of Rome gathered at the River Tiber, just south of the cattle market, near the Greek Quarter. The sun was bright but not hot. The breeze was cool and healing. Peter waded into the shallow part of the river near the bank and motioned for the catechumens to follow him. Stachys, dressed in a new white tunic, was the first to move down into the water. He was followed by a few families with their children and several others. Stachys was suddenly hit by the gravity of what was about to take place, and he felt like he needed more time to prepare for it, so he stepped aside to let the others go first.

When it was finally his turn, Stachys walked up to Peter, the cold waters of the Tiber swirling past his thighs. He bowed his head, and Peter put one hand on Stachys’s head and the other on his shoulder. “Stachys,” Peter began, “Do you believe in the one true God, and no others?”

“I do.”

“Do you believe that there is no salvation but through his unique Son, Iesua the Christos, and that there is no other name under heaven by which we may hope to be saved?”

“I do.”

“Do you believe that he conquered death by dying and inaugurated the resurrection by rising from death?”

“I do.”

Peter gently pushed Stachys down into a kneeling position. The cold water was now up to Stachys’s shoulders. “Stachys, I baptize you in the name of the Father . . . and of the Son . . . and of the Holy Spirit . . . as our Lord Iesua commanded us to do.” With each of the names of the persons of the Trinity, Peter pushed Stachys’s head underwater, then pulled him up again by the back of his tunic. Maria was smiling so hard her face was starting to hurt. But she didn’t care. This was the day she had been waiting for.

Then Peter put both of his hands on Stachys’s shoulders. “Stachys, receive the Holy Spirit.”

When the baptisms were done, and all of the newly baptized Christians were confirmed in the faith with the gift of the Holy Spirit, Peter addressed the group. He could see a small crowd gathering behind the Christians as onlookers stopped to see what they were doing. He recognized this as a chance to plant the seeds of faith in whoever might be listening.

“Brothers and sisters,” he shouted. “The one true God sent his Son into the world to offer forgiveness and reconciliation. All he asks is that you turn to him in faith and remain faithful to him alone. When you do this, and are initiated to his table in the way we have done here today, you receive two gifts: forgiveness of your sins and the indwelling of the Holy Spirit. These gifts will lead you to salvation and eternal life. This is the promise that the one true God has made to you, and to your children.”

As Peter led the newly baptized Christians out of the river, the first to congratulate Stachys was Ampliatus. He grabbed Stachys’s hand and shook it vigorously. “Welcome to the Lord’s table . . . brother.”

Stachys sighed and smiled. He returned the handshake. “Thank you . . . brother.”

“Pardon me,” Maria said with a tear in her eye. “May I give my husband a kiss?”

For the rest of the day, Peter visited all four of the active home gatherings, talking to as many of the people as possible and asking everyone to spread the word that the evening agapē meal and worship would be for all of the Christians of Rome, all together at the house of Senator Pudens. While he was at Stachys and Maria’s house he blessed the unions of Stachys and Maria and of Philologus and Julia.

Sabina watched the couples as Peter blessed them. She squeezed Urbanus’s arm. When it was over she whispered to him, “I want that. I want that kind of marriage. Not a contract, but that . . . what did he call it? One flesh. Where I have only you, and you have only me. And we don’t have to worry that one of us is going to leave if a better match comes along. Is there any way we could have that?”

Urbanus turned to face his wife. “My dear, you’re the one who married beneath your status. If anyone were going to worry, it would be me. But the truth is, I don’t think we’re going to have any choice in the matter. That’s the kind of union that’s expected of these Way-followers. It will be expected of us . . . when we join them.”

That evening, Pudens’s atrium was overflowing with joyful people, all excited to have Peter among them again. They milled around as Peter walked through the group greeting old friends and meeting new ones. Urbanus and Sabina arrived with their daughters, Tryphaena and Tryphosa. After a while Pudens called everyone together and welcomed them to his home, and then led the group into his private auditorium, where he often read to his household or sponsored lectures. The walls were painted with colorful and elaborate patterns of garlands and geometric designs. An expensive-looking chair with a back on it was placed at the front of the room on a platform, with a curtain behind it. The men gathered on the left side of the room, and the women and children on the right.

Peter deferred to Linus, who led the opening prayer. After the prayer, Maria chanted, “Lord, have mercy,” and the whole group echoed back the words.

Then Peter nodded to Marcus, who took up his scroll and began to open it. Marcus said, “I’m so glad our brother Peter is back in Rome. As you know, I’ve been working on writing the story of the time when Iesua was with his disciples. I call it The Memoirs of Peter. But I can’t finish it without more help from the man himself.”

Peter interrupted him. “Brother Marcus, please don’t call it The Memoirs of Peter. My name should not be in the title. It’s not really about me. I hope you’re including as many of the stories about Iesua as you can, so if anything, it’s the memoirs of all the apostles.”

Marcus nodded humbly and began to read:

Iesua took Peter, James, and John and led them up a high mountain apart by themselves. And he was transfigured before them, and his clothes became dazzling white, such as no fuller on earth could bleach them. Then Elijah appeared to them, along with Moses, and they were talking with Iesua. Then Peter said to Iesua, “Teacher, it is good that we are here. We will make three tents: one for you, one for Moses, and one for Elijah.” He didn’t know what he was saying because they were so terrified. Then a cloud came, and overshadowed them. Then a voice came from the cloud, saying, “This is my beloved Son, listen to him.”

The people gathered were amazed at the story, and after a brief silence, they began asking Peter to tell them what it was like to be there. Peter sat down in the chair at the front of the room. He smiled and said, “This is another reason why your memoir should not be named after me. I just don’t come out looking all that good in these stories. Oh well, the Lord wants me to stay humble, I suppose. What was it like to be there? To be honest, I almost wasn’t there. I was so scared I almost ran away.”

Peter was lost in thought for a brief time. “I was with Iesua and the Zebedee brothers. We were on the holy mountain, and our Lord willed that we should see the majesty of his resurrection body. Looking back on it now, he looked very much the same as he did after his resurrection, when it was hard to recognize him. But that time, the light of his glory was so bright I fell in a faint, and my eyes were blinded. I remember seeing nothing, but hearing his voice as he was talking with Moses and Elijah—though I couldn’t hear what they were saying. When I could see again, well, I can’t even describe it to you. I’ll tell you, that thing I said about building three tents? I was just trying to get Iesua’s attention so he would remember we were there and not burn us to a crisp with his glory. I didn’t know what I was saying. But I’m glad I didn’t run away, because if I had, I might not have heard the Voice. You know, many people started to follow Iesua, but a lot of them didn’t last. They left him. Yes, it’s true. But I could never leave him, in part because I heard the Voice.”

Peter thought for a time and then went on. “All of us here, we all came from different places. It seems as though so many people in Rome are from somewhere else. Judea, Phrygia, Cappadocia, Egypt—even Asia. Some of you were there at Pentecost. A few of us knew Iesua personally. But it doesn’t matter where we come from or who we were before. Because now we are Christians. Now we are the church. I heard Paul say something at the council. He said no matter whether we are Judean or not, slave or free, man or woman, we are all one in our Lord Iesua, the Christos. In fact, we all come to him like the thief on the other cross, trying to have faith, hoping he will give us that peace that comes from the hope of paradise.”

A voice from the back of the room shouted, “When will Iesua come back? It’s been almost twenty years!”

Peter smiled. “It isn’t for us to know times or seasons. But the fact that he has delayed his return is an act of mercy. He’s waiting for as many people as possible to come to reconciliation with God through him. Also, since he seems to be delaying his return, it’s good that Marcus is writing down the story, for as you know, some Christians have already died, and more may die, and we may even find ourselves with second- and third-generation Christians—our descendants who will have to hand the faith on to people who never met anyone who walked with Iesua. But don’t worry, a thousand years are like a day to God. So any delay does nothing to diminish the promise.”

“So where was I?” Peter continued. “Yes, the hope of paradise. The transfiguration and resurrection of our Lord show us that we are not to believe the fables of an afterlife as a shadowy existence, as the myths of Hades and Elysium claim. And we are not to believe in the afterlife as a disembodied existence, as the philosophers teach. No, we believe in the resurrection, which even King David prophesied in the psalm that begins, Keep me safe, O God, in you I take refuge. The philosophers, in fact, can’t even agree on what it means to be blessed. The Pythagoreans say reason is the key to the good life. The Sophists claim individualism and relativism. Socrates said it was law, and Plato said it was justice. The Skeptics say the best thing you can do is admit you don’t know. The Cynics prefer detachment, and the Epicureans pursue pleasure. The Stoics claim to have defined virtue, but look around you—are the Romans virtuous? Are they happy? No, Iesua said that the ones who are blessed are the poor, and those who mourn, and the humble, and the hungry. Those who show mercy, and those who make peace. The pure . . . and the persecuted.”

Marcus muttered to himself, “I should be writing this down.”

Peter continued, “But why should those people be happy or feel blessed? Because they know they will inherit the resurrection life in God’s eternal empire. They put their hope in something bigger than life.”

Cletus led the prayers, which went on for quite a long time with such a large group. But eventually the prayers came to a conclusion, and Pudenziana and Prassede brought the bread and wine forward and placed them on a small table in front of Peter. Peter nodded to Rhoda, who led the gathering in the singing of a text from the prophet Isaiah:

Holy, Holy, Holy, is the Lord of hosts.

All the earth is filled with his glory!

Holy, Holy, Holy, is the Lord God Almighty,

Who was, and is, and is to come!

Peter led the group in the Our Father, and then they all prepared to receive the Thanksgiving Bread by reciting a prayer of confession from the Psalms:

Be gracious to me, O God, according to your mercy. According to the greatness of your compassion, blot out my transgressions. Wash me thoroughly from my iniquity, and cleanse me from my sin. For I know my transgressions, and my sin is ever before me. Against you, and you alone, I have sinned and done what is evil in your sight. . . . Create in me a clean heart, O God, and renew a steadfast spirit within me. Do not cast me away from your presence, and do not take your Holy Spirit from me. . . .

After Peter said the prayers over the bread and the cup, he held them up for all to see. He raised his voice and said, “I heard Iesua say, Whoever eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life, and I will raise him up on the last day. For my flesh is true food, and my blood is true drink. Whoever eats my flesh and drinks my blood lives in me, and I in him. As the living Father sent me, and I live because of the Father, so whoever eats me, will also live because of me. This is the bread which came down out of heaven; not as the ancestors ate and died; but whoever eats this bread will live forever.

“Later, Iesua would say, Take this, all of you, and eat it: this is my body which will be given up for you. Take this, all of you, and drink from it: this is the cup of my blood, the blood of the new and everlasting covenant. It will be shed for you and for all so that sins may be forgiven. Do this in memory of me. Look—here is the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world.” Peter broke the bread, and all the baptized solemnly came forward to receive it from him.

When Stachys received the bread, he held it in his hand and looked at it. He hesitated, letting the gravity of the moment sink into his mind. He remembered some words of Iesua that he had heard. Remain in me, and I will remain in you. He ate the bread, and a sense of peace washed over him, and he thought he was beginning to understand what they meant when they wished each other the peace of the Christos. When the wine was passed to him, he tried to take a small sip. He tried to be unselfish and make sure he wasn’t taking too much. But he wanted the blood of the Christos, and he couldn’t help himself. He took a big gulp and smiled.

After all of the baptized had received the body and blood, Peter addressed the gathering. “I would like to say a few things before we sing our song. First of all, I’ve asked one of our newest initiates to join the order of deacons. Brother Stachys has accepted the responsibility of service.” Everyone expressed their approval and wished blessings on Stachys as he blushed. “And finally, we will be taking a collection for the poor brothers and sisters of Rome. Many of us here are unemployed, or have not had enough work recently, and are struggling to survive.” Now it was Philologus and Julia who blushed. Peter smiled at them and continued, “Those who have some resources to spare are asked to share what they have. Brother Stachys, in his first official act as a deacon, will be going around the room with a basket. Please be generous.”

Maria and Rhoda led the hymn together. The people all knew the song because they had been singing it in their individual gatherings for a while, but this was the first time that all the Christians of Rome sang it together.

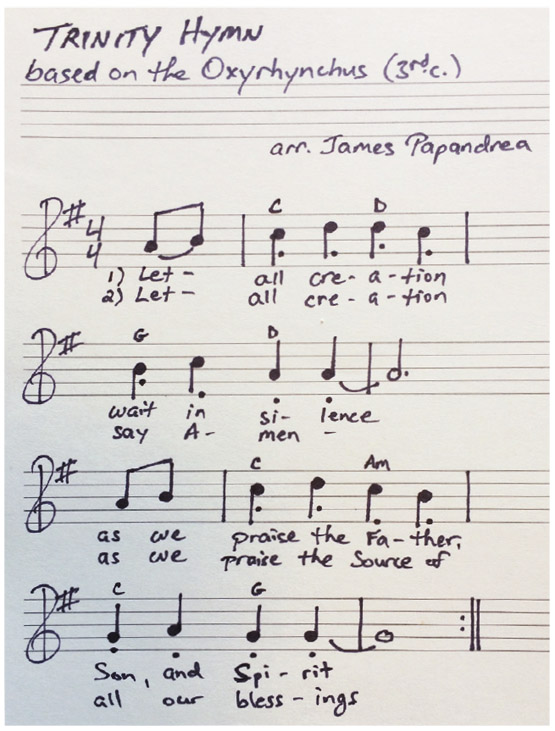

Let all creation wait in silence, as we praise the Father, Son, and Spirit

Let all creation say Amen, as we praise the source of all our blessings

Worship in Early House Churches

Just as conversion in the early church was not simply an individual’s decision, the group mentality of the Roman personality meant that worship also was not simply a matter of personal devotion. Most early Christians did not think in terms of personal Scripture study or personal prayer and meditation. For early Christians, worship was more about celebrating the group identity as people who gathered at the table of the Lord and who collectively identified with Jesus Christ as their Savior. The idea of a “personal” Savior would probably not have made much sense to them.

We don’t actually know much about what music and singing was like in the early decades of Christianity. There may have been varying “degrees” of what might be called hymnody, on a spectrum going from rhythmic speaking, to intoned speaking, to chanting, to melodic singing. The songs included in our story are based on the theory that the apostle Paul quoted hymns in his letters. However, there is a lot of debate among scholars about whether the quoted passages are in fact hymns or perhaps prayers. In any case, if Paul is quoting preexisting material, then the content of these songs or prayers is very significant, since it represents the earliest Christian theological statements we have in written form. For more on these pre-Pauline hymns, see my book Trinity 101 (Liguori, 2012).

When we ask what early Christian music may have sounded like, the question becomes even more complicated. No doubt the music of the first Christians was not very different from the music of ancient Jews, but in a place like Rome, it also must have been influenced by Greek and Roman forms of music. We know for sure that they did sing, and Paul encourages his people to sing “psalms and hymns and spiritual songs” (Eph 5:19; Col 3:16; see also 1 Cor 14:15, 26). Unfortunately, we don’t know how Paul defined these three types of songs or whether they were really three different things at all.

Singing in the first churches was probably responsorial, that is, a call and response, with a leader singing a line and the people repeating it. Or perhaps a soloist sang a phrase, and the people responded by singing “Amen.” Eventually the congregations would have memorized longer passages, possibly set to music, and sung them in unison. But even if the songs were set to music, they did not have harmony the way modern music does, with different singers singing different notes based on chords. As far as we know, all singing in the church was in unison until the Middle Ages.

We also don’t know for sure whether they used musical instruments at all. If the heavenly worship scenes in the book of Revelation are a reflection of actual worship, then the early Christians may have used lyres (usually translated “harps”). They may also have used pan pipes. However, even then the music was not so much an accompaniment as it was a guide for the singers. The instrument would simply play the melody as the people sang along. In later centuries we know that many musical instruments (horns, drums, cymbals) were probably avoided by the church due to their association with pagan worship or erotic dance. Note that the instrument often translated “flute” was not actually a flute but was a reed instrument called an aulos, something like an oboe or clarinet.

The song in the story near the end of this chapter is a simplified version of an early Christian song known as the Oxyrhynchus hymn. This was a third-century hymn with music notation found on a papyrus in the city of Oxyrhynchus. The version I’ve adapted is a much-simplified, modernized arrangement, but the English words do convey the theme of the Greek text, and the tune is based on melodic phrases from the music. I’ve also added modern chords so that I can use it as a worship chorus with my students. I hope you will try it yourself and sense a connection with those who worshiped in the early centuries of our faith.

Figure 7.1. Modernized version of the Oxyrhynchus hymn (third century), adapted and arranged by the author

As the people talked and sang their way out of the gathering, Stachys went around with the basket collecting donations. When he came to Urbanus and Sabina, they stopped him. Urbanus said, “Stachys, my friend. We’ve told your man Peter that we want to join the school of the Christians, both of us, and our daughters. It may ruin our reputation, but then I’m not sure we will have much of a reputation left after all that’s happened.”

Sabina smirked. “Of course, my reputation was ruined when I married him.”

Urbanus sighed, smiled, and put his arm around Sabina. “My wife’s vocation is to ensure my humility. In any case, Peter said that we would need sponsors—to vouch for us when we’re ready to take up the lifestyle. The irony here is not lost on me, but I’m asking you, will you and Maria be our sponsors?”

Stachys smiled. “Of course, my friend. Nothing would make us happier. And soon we will call each other brothers.”

Urbanus pulled out his small leather pouch and fished out his most prized possession—the rare gold coin. He rubbed it for luck, then dropped it in the basket.