Chapter 10

Mobile device forensics

Abstract

In Chapter 10, we’re going to take a closer look at cell phones and the technology that powers them. We’ll look at the types of networks as well as the components that form them. Cell phones are not the only mobile device with potential evidentiary value. Global Positioning Systems (GPSs) are gaining more and more attention from investigators. As such, we’ll look at what kind evidence we may be able to recover from a GPS unit. Finally, this chapter will examine the special handling techniques required to preserve fragile evidence on these wireless devices.

Keywords

Global Positioning System (GPS)

TDMA

GSM

Subscriber Identity Module (SIM)

Personal Identification Number (PIN)

Personal Unlock Key (PUK)

call detail records

Short Message Service (SMS)

triangulation

waypoints

“Three objects were considered essential across all participants, cultures and genders: keys, money and mobile phone.”

—Jan Chipchase, Nokia

Information in this chapter

• Cellular Networks and How They Work

• Overview of Cell Phone Operating Systems

• Potential Evidence Found on Cell Phones

• Collecting and Handling Cell Phones as Evidence

• Cell Phone Forensic Tools

• Global Positioning System Function and Potential Evidence

Introduction

The phones riding on our hips and sitting in our pockets are true marvels of technology. These “mini-computers” are capable of delivering much of the same functionality that was once the lone province of desktops and laptops. We can browse the Internet, send and receive e-mail, shoot pictures and videos, and plot our location on a map, just to name a few of the possibilities.

Cell phones and other mobile devices can make a case airtight. Just ask Dan Kincaid of Boise, Idaho. When the Boise police arrested Kincaid for burglary, they also seized and searched his Blackberry cell phone. It paid off. His e-mail history contained several messages that would eventually help convince him to plead guilty. After being spotted, Kincaid e-mailed his girlfriend, saying, “Just trying to find a way out of this neighborhood without getting caught.” “Dogs bark if I’m between or behind houses…” He went on to write, “Cops know I have a blue shirt on. … I need to get out of here before they find me” (Shachtman, 2006).

At their core, today’s smart phones are fundamentally computers with radios attached to them. There is an ever-evolving world of cell phone hardware, with no slowdown in sight. Like their larger cousins, these small-scale devices can create artifacts that can be recovered and used as evidence.

Cellular phones and other mobile devices present yet another challenge for examiners. Walk into any cell phone store and you’ll be confronted with a vast array of cell phone makes, models, and operating systems. The various devices in turn support many different services and applications. To further complicate things, there is no established hardware interface. You’ve probably run across this issue one time or another when you upgraded your phone. Odds are, when you got a new phone, you had to get a new charger and data cables as well. Keeping pace with the cabling, operating systems, and so on is quite a challenge. The good news is that this seems to be getting better, with many phones now including mini-USBs in their handsets.

Cellular networks

Evidence can be located not just in the phone or memory card, but on the network itself. As examiners, we need to understand the basic operation of cellular networks and the location(s) of any potential evidence.

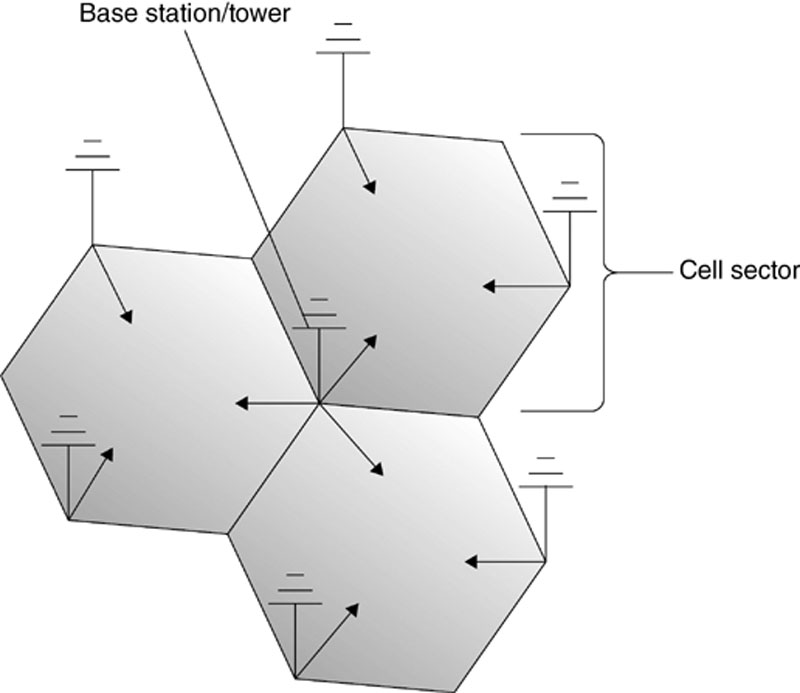

As the name implies, each cellular network is made of individual cells. Each cell uses a predetermined range of frequencies to provide service to a distinct geographic area. The size and shape of each cell varies. In fact, they can vary wildly. They can cover a few city blocks in an urban environment to more than a couple of hundred square miles in the country. The type of terrain, particularly any obstructions, is the limiting factor; see Figure 10.1.

Figure 10.1 The layout of a typical cellular network. (Illustration by Jonathan Sisson.)

The strength of the radio signal emitted from each cell is closely controlled. This is done purposefully to limit its range. By limiting the range, providers can reuse the relatively limited number of frequencies they have to work with.

Each cell has a base station that consists of an antenna (or mast) along with the related radio equipment. Together, they are known as a cell site. These cell sites deliver coverage to the individual cells. You’ve probably seen these large towers along the interstate, for example, or smaller ones on rooftops in more urban locations. Normally, each cell tower will have three panels per side. The middle panel is usually the transmitter, with the other two being receivers. The receiver panels constantly listen for incoming radio signals.

It may surprise you to know that the cell sites are not located in the center of each cell. They are actually at the junction of multiple cells, facilitating service as subscribers move from cell to cell.

Cellular network components

It takes quite a bit of infrastructure to get your phone call from that remote location back to your office downtown. Forensically speaking, each of these components could potentially provide information relevant to an investigation.

A base station consists of the antennas and related equipment.

A Base Station Controller (BSC) regulates the signals between base stations. This function is critical as phones move from place to place.

The Mobile Switching Center (MSC) processes calls within the network. As a key piece of the wireless network, the MSC holds a tremendous amount of possible evidence. It also coordinates calls between different wireless networks as well as landlines. The MSC handles SMS messages as well. The call detail records and logs are found here.

The Visitor Location Register (VLR) is a database that is linked to an MSC. All mobile devices currently being controlled by that MSC are recorded in the VLR. Interworking functions serve as doorways outside data networks such as the Internet.

Information about individual subscribers is collected in the Home Location Register (HLR). This information includes subscriber identification, billing, and services received, along with the current location of the device. The HLR also stores encryption keys. The HLR supports the Authentication Center (AuC), which is used to control access to the network. The AuC screens connections, blocking unauthorized users (Jansen and Ayers, 2007).

Text or SMS messages are the responsibility of the Short Message Service Center (SMSC). Messages may be recovered from the SMSC, but there is no hard-and-fast rule dictating how long these messages must be kept by individual providers. It is up to the individual provider to determine how long that information is kept (Jansen and Ayers, 2007).

It’s important to note that your cell phone is regularly communicating with the nearest cellular antennae, even if you’re not talking on it. When you turn on your cell phone, it automatically begins searching for the nearest cell site. Once the antenna is found, the phone then transmits identification data so the network can verify who you are and whether you have authorized access. This information would include details such as the cell phone number and the name of your service provider.

As you drive, your “connection” to the network must be transferred from cell tower to cell tower. This transfer is known as a handoff. The handoff is made as the signal strength begins to fade. Not all handoffs are handled the same way. For instance, Global System for Mobile Communication (GSM) and Code Division Multiple Access (CDMA) for networks handle them differently. A GSM network uses what is known as a hard handoff. Here, the phone can only attach to one tower at a time. The conversation is separated from the current tower and passed to the new one. The phone will then switch to the new tower’s frequency. In contrast, CDMA handoffs are considered soft handoffs. Here, a phone can connect to multiple towers at once, using the tower with the strongest signal.

Records showing when a certain phone is connected to a specific tower can be used to put someone (or, more precisely, the person’s phone) in the vicinity of a crime or to establish an alibi.

Once your call hits the cell tower, it’s then transferred to the MSC. If the call is destined for a phone that is out of the network, the MSC will pass the call to the Public Switched Telephone Network (PSTN). The PSTN will then direct the call to its intended recipient.

We’ve all experienced dropped calls or a loss of signal at one time or another. One of the potential causes is dead spots. Dead spots can be caused by a gap in the cell coverage or obstructions to the signal. Cell phones are heavily dependent on having a clear and unobstructed (or very close to it) path to the cell tower. Obstructions can be tall buildings, mountains, and large trees.

Cell phones support two kinds of messaging services, SMS and Multimedia Messaging Service (MMS). SMS are what we normally refer to as text messages. We get the name Short Message from the limitation of the maximum size of each message: SMS messages have a maximum length of 160 characters. MMS offers improved functionality over SMS. MMS messages aren’t limited to 160 characters.

Types of cellular networks

Cellular networks can be differentiated or defined in how they transmit data. These transmission schemes include CDMA, GSM, and Integrated Digitally Enhanced Network (iDEN).

Code division multiple access

CDMA was originally a military technology that was eventually released for use by the public. CDMA uses spread spectrum technology to transmit data. This technology permits several phones to send and receive through a single channel. Each part of these separate conversations is labeled with a specific digital code. The carriers that use CDMA technology include Sprint, Verizon, Alltel, and NEXTEL. CDMA phones typically do not use SIM cards. CDMA networks use Electronic Serial Numbers (ESNs) to identify individual handsets (Barbera, 2010).

Global system for mobile communication

As the name suggests, GSM phones can be used internationally. GSM uses Time Division Multiple Access (TDMA) technology. Worldwide, GSM is the most widely used transmission mode. Unlike CDMA, GSM phones use SIM cards. GSM carriers include AT&T, Verizon, T-Mobile, and Cellular One. The International Mobile Equipment Identity (IMEI) is used to identify handsets (Barbera, 2011).

Integrated digitally enhanced network

iDEN provides two-way radio-like functionality, also known as “Push to Talk.” Like GSM phones, they also use SIM cards. iDEN carriers include NEXTEL, Sprint, and Boostmobile.

Prepaid cell phones

At their core, prepaid phones operate like other cell phones in that they use radios to transmit data and must connect to a network. The difference with prepaid phones is that they create some significant investigative hurdles, particularly when trying to identify the subscriber. For one, they can be paid for completely with cash, essentially leaving little to nothing in the way of a paper trail. This makes identifying the purchaser much harder.

Like other cell phones, however, we can identify the area where the phone is being used as well as the calls that are sent and received. With prepaid phones, the information we’re looking for will be held by two entities. The phone provider will hold any subscriber information, and the network provider will maintain the call detail records.

Operating systems

A phone’s operating system (OS) has a significant impact on any forensic examination. The OS determines what artifacts are created and how they are stored. Modern cell phone operating systems include Symbian, Apple iOS, Windows CE and Windows Mobile, Google’s Android, and Blackberry OS.

Originally, the Symbian OS was a product of a partnership between Nokia, Sony Ericsson, Motorola, and Psion. Sony Ericsson rolled out the first Symbian-run phone in 2000. In 2008, Nokia bought the rights to the OS. Nokia recently made Symbian open source. It’s used today in Nokia and Sony Ericsson handsets (Barbera, 2010).

Blackberrys were first introduced in 1999 by the Canadian company Research In Motion (RIM). Businesses and governmental entities are heavy Blackberry users. Blackberry phones synchronize with Novel’s GroupWise and Microsoft’s Exchange. As such, they are quite proficient in handling e-mail, calendars, and the like. The Blackberry OS supports multitasking as well as a variety of applications. This operating system is proprietary, and versions are specific to each carrier. That means that the Verizon version of a specific phone would be different from the AT&T edition (Barbera, 2010).

Android is an open-source OS that is currently developed by Open Handset Alliance. In 2005, Google acquired the Android OS from Android, Inc. In 2007, the Open Handset Alliance was formed and it has been developing the OS ever since. The Open Handset Alliance “is a group of 84 technology and mobile companies who have come together to accelerate innovation in mobile and offer consumers a richer, less expensive, and better mobile experience” (Open Handset Alliance, 2007). Some of the members include Sprint, T-Mobile, LG Electronics, Inc., Kyocera, Motorola, Google, and eBay. Thousands of third-party apps are available to augment Android’s core functionality. Android is found on handsets produced by Motorola, Sony Ericsson, and HTC (Barbera, 2010).

Apple’s popular iOS can be found not only on the iPhone but also on other mobile devices, such as the iPad and the iPod touch. iOS is based on Apple’s Mac OS X, which is used on their laptops and desktops. iPhones make heavy use of third-party apps that are purchased/downloaded from the Apple App Store.

Windows Mobile is Microsoft’s OS developed for the smart phone and mobile device market. Like its competitors, Windows Mobile also supports a huge array of apps.

Cell phone evidence

Now that we’ve looked at how cell phones and networks function, we can look at some of the information they hold that may qualify as evidence. It’s important not to focus on one source, as relevant evidence can be found in multiple locations within the handset and the network.

Table 10.1 lists some of the potential evidentiary items found in modern smartphones.

Table 10.1

Potential Smartphone Evidence

| Call History | Text Messages | |

| Pictures & Video | Deleted Text Messages | Browser History |

| Contacts | Location Information GPS | Chat Sessions |

| Calendar | Voice Memo | Documents |

The Personal Identification Number (PIN) is used to secure the handset. Three consecutive, unsuccessful attempts to enter the correct PIN will result in the user being locked out. The Personal Unlock Key (PUK) will be needed to unlock the SIM after this lockout has occurred. Typically, a PUK can only be supplied by the provider of the SIM card (Barbera, 2010).

You have probably noticed when typing an e-mail or text on your phone that, many times, the phone will complete words for you. This is called predictive text. Predictive text was developed to make texting easier on phones that lacked full QWERTY (the standard computer and typewriter keyboards). Those phones use three letters per key, forcing the user to scroll through multiple letter options before selecting one. With predictive texting technology, the device attempts to predict the word most likely intended by the user. These guesses are based on a database dictionary containing thousands of words, names, abbreviations, slang terms, and so on (Mobile-phone-directory.org, 2009).

What is most interesting, from a forensic perspective, is that these systems are capable of learning. Words, abbreviations, slang, and the like entered by the user is assimilated into the database. E-mail addresses and URLs can also be stored. If this database is recovered, it can produce some interesting evidence. For example, pedophiles could have routinely entered common abbreviations for child pornography, such as CP. A drug trafficker could routinely enter slang or a code word for a given product when texting a buyer.

Several companies produce this technology. Some examples are Tegic Communication’s, T9 (www.T9.com), Motorola’s iTap, and ZiCorp’s eZiText (Kessler, 2011).

Call detail records

Call Detail Records (CDRs) are normally used by the provider to troubleshoot and improve the network’s performance. CDRs are also valuable to examiners. They can show us:

• Date/time the call started and ended.

• Who made the call and who was called.

• How long the call lasted.

• Whether the call was incoming or outgoing.

• The originating and terminating towers.

Although the CDRs can tell you a lot, what they cannot tell you is who actually made the call.

You get what you ask for; therefore, it is important to understand the difference between the CDR and the subscriber information. Subscriber information and CDRs are not the same. Typical subscriber information would include things such as the name, address, and telephone number. Other items included with subscriber information are account numbers, e-mail addresses, services, payment mechanisms, and so on.

Every service provider keeps all of these records for a predetermined period of time. The time period is spelled out in their data retention policies. The retention period is also not uniform across all of the data types. For example, some carriers may keep SMS data for only seven to fourteen days. By contrast, cell sector information could be kept for a year or longer. The takeaway here is that you don’t have an unlimited amount of time to file the necessary paperwork to ensure that the records you seek won’t get purged.

Carriers generally maintain meticulous records of subscribers and their activities for billing and other purposes. This stockpile of information can be enormously helpful during an investigation. These carrier records can tell us the subscriber’s name, address, additional phone numbers, Social Security number, and so on. The credit information on file can give investigators billing addresses, credit card numbers, and more.

The CDRs describe the specifics of each incoming and outgoing call. These should not be confused with toll records. Toll records refer to landline information rather than mobile phones. When asking for the call detail records, you must specify a date range. It’s a wise practice to pad your request with a day or two on both ends.

The CDRs, when combined with the physical addresses of the towers, can show us a call’s origination and termination locations. These records also show the cell sites that were used, the length of the call, the time the call began, the numbers dialed by the target phone, and so on (Jansens and Ayers, 2007).

The billing records do not represent a complete list of inbound and outbound calls. The call logs will include data that have not yet made it into the billing system.

Information kept by the carriers will likely have a short, predetermined shelf life. Each carrier has some discretion on how these data are preserved and how long they’re stored. This is usually described in the company’s retention policies. In light of this practice, the legal paperwork should be generated and served sooner rather than later. This will help to ensure that your evidence won’t get purged before it can be preserved and collected.

Cell phones can be located (with varying degrees of accuracy) by a few different means. Triangulation is one of the better-known methods. In triangulation, the phone’s approximate location is determined using its distance from three different towers. The distance is calculated by determining the signal delay from the phone (or handset) to the three towers. A directional antenna can also be used for this purpose. Again, the signal delay is used to determine the distance, but this time, only two towers are needed since they are also able to determine the direction. Finally, the location can be determined via GPS using latitude and longitude.

Collecting and handling cell phone evidence

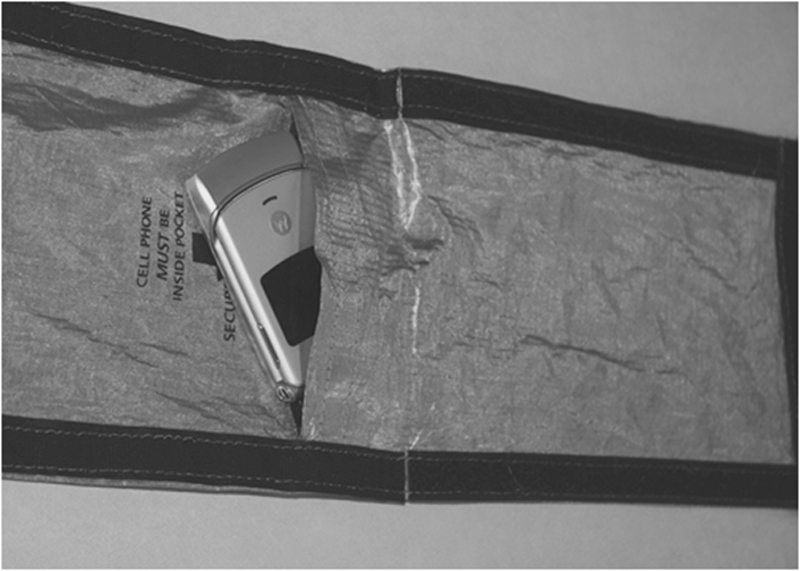

Because cell phone data are not unlike other forms of digital evidence, the fundamental principles in handling digital evidence apply to cell phones as well. Job one when dealing with cell phones is isolating the target phone from the network. Isolating the phone is imperative. Aside from the danger of it being remotely wiped (by the suspect or carrier), any inbound calls, messages, or e-mails could overwrite any potential evidence. We can effectively isolate the phone using a Faraday bag or arson can. A Faraday bag, shown in Figure 10.2, is a special container constructed with conductive material that effectively blocks radio signals. An arson can is really nothing more than a clean, empty paint can. These containers can be found in hardware or home improvement stores.

Figure 10.2 A Faraday bag and cell phone.

If the phone is on when you recover it, leave it on. If there will be a significant delay in getting the phone to the lab, you may want to consider turning it off. This is done to ensure that the battery doesn’t completely drain. If it does, you run the risk of locking the phone. If the phone is protected with a PIN, turning the phone off will result in the phone being locked when it’s turned back on.

Isolating the phone with the power on creates some concerns regarding the battery life. Remember, while the phone is on, it will continually attempt to connect to the network, further draining the battery. A dead battery could also trigger the security function, locking up the phone.

If the phone is off, we can remove the battery as well as remove and initial the SIM card. We’ll also want to photograph the phone, front and back. During this process, we’ll want to pay particular attention to the identifying numbers underneath the battery (the IMEI, ESN/MEID). We’ll also want to isolate the phone from the network, just like a powered-on phone.

Before conducting a forensic exam, it’s important to identify the make and model of the handset you’re dealing with. This information can help you get a full understanding of the phone’s functions, features, and capabilities. The make and model of the phone can be typically found under the phone’s battery. This same information can also be found in the phone’s file system.

As with computers, we only want to access or examine the original evidence as an absolute last resort. Ideally, a forensic tool should be used to first acquire the data, giving the examiner a copy to work with. In the end, however, a manual examination may be the only alternative. Should this be necessary, you will have to articulate your reasoning for taking this course of action. Detailed documentation will be very helpful in accounting for your interaction with the device and establishing the integrity of any evidence that is recovered. Documenting a manual examination typically relies heavily on photographs as opposed to the digital evidence itself. In this instance, the examiner painstakingly navigates through the phone, taking photographs of the screens as he or she goes.

Voicemail is another potential source of evidence that shouldn’t be overlooked. Typically, to access the voicemail, you will need the password-reset code from the carrier. When collecting voicemail evidence, there are a couple of options. The carrier can simply provide you with an access code or can deliver a copy of the data itself. This detail should be worked out early on with the provider, especially if you prefer one method or format to another.

At the scene, you should be on the lookout for additional handsets, SIM cards, and the related power and data cables. The power cable will help the lab ensure that the volatile memory is left intact until it can be properly collected and examined. Don’t forget that, while the phone is on, it will continually seek to connect with the network, rapidly draining the battery.

Subscriber identity modules

Subscriber Identity Modules (SIMs) can be valuable evidence all by themselves. They store a vast amount of information and should be collected and analyzed.

The SIM contains a couple of numbers that will be of particular interest. The first is the International Mobile Subscriber Identity (IMSI). The second is the Integrated Circuit Card Identifier (ICC-ID). The IMSI is used to identify the subscriber’s account information and services. The ICC-ID is the serial number of the SIM card itself. The SIM can contain:

• Subscriber identification (IMSI)

• Service provider

• Card identity (ICC-ID)

• Language preferences

• Phone location when powered off

• User’s stored phone numbers

• Numbers dialed by the user

• SMS text messages (potentially)

• Deleted SMS text messages (potentially)

The SIM cards contain several individual components including a processor (CPU), RAM, Flash-based nonvolatile memory, and a crypto-chip. They are used in all phones but are present in GSM, iDEN, and Blackberry handsets.

A PIN may be in place to protect the SIM data. PINs are four to eight digits in length. As an added layer of security, only three attempts may be made to enter the correct PIN. After the third unsuccessful attempt, the data can only be accessed with an eight-digit PUK, along with a new PIN. Attempts to enter the PUK are also limited. After 10 failed attempts, many SIM cards will permanently deny access with a PUK.

Cell phone acquisition: physical and logical

The data on a cell phone can be acquired in one of two ways: physically or logically. A physical acquisition captures all of the data on a physical piece of storage media. This is a bit-for-bit copy, like the clone of a hard drive. This acquisition method captures the deleted information as well. In contrast, a logical acquisition captures only the files and folders without any of the deleted data. Data can be collected using nonforensic tools, such as those used to synchronize or back up the data on the cell phone (Jansen and Ayers, 2007). While this process is similar to the one used to acquire a hard drive, there is one important difference: In this instance, no write-blocking device is used. The phone must be able to interact with the phone’s hardware and software.

A manual examination entails interacting with the device via the keypad or touch screen. Although examining or interacting with the original evidence is never our first choice, sometimes it may be the only option. For example, in cases where time is of the essence, it may be necessary to forgo proper forensic procedures. Those situations may include locating a missing child or preventing an imminent violent act of some sort. In other situations, it may not be possible to even mine the data or extract them in a way that would preserve their integrity. This could happen in cases where forensic tools and techniques haven’t caught up with the latest technology.

Cell phone forensic tools

As you might suspect, there are many, many different tools available to examine a phone forensically. These tools can come in the form of hardware or software. One of the realities is that not all of these tools support all cell phones. To further complicate matters, two tools that actually support a given phone may not read and recover the same information.

What follows is a sampling of the available tools for cell phone forensics. A close examination of the functions and features shows that no single tool does it all. One glaring difference is the number of phones that are supported. Budget permitting, most labs will have multiple tools available to increase their capabilities.

BitPim is a robust open-source application that was not built for forensic purposes. BitPim is designed to work with CDMA phones that are produced by several vendors, including LG and Samsung, among others. BitPim can recover data such as the phonebook, calendar, wallpapers, ring tones, and file system (http://www.bitpim.org/).

Oxygen Forensic Suite is a forensic program specifically designed for cell phones. It’s a tool that supports more than 2,300 devices. It extracts data such as phonebook, SIM card data, contact lists, caller groups, call logs, standard and custom SMS/MMS/e-mail folders, deleted SMS messages, calendars, photos, videos, JAVA applications, and GPS locations (http://www.oxygen-forensic.com/en/).

Paraben Corporation offers several hardware and software products targeted to mobile device forensics. In addition to cell phones, their tools also support GPS devices such as those from Garmin (http://www.paraben.com/handheld-forensics.html).

AccessData’s MPE+ supports more than 3,500 phones. It’s an on-scene, mobile forensic recovery tool that can collect call history, messages, photos, voicemail, videos, calendars, and events. It can analyze and correlate multiple phones and computers using the same interface (http://accessdata.com/products/computer-forensics/mobile-phone-examiner).

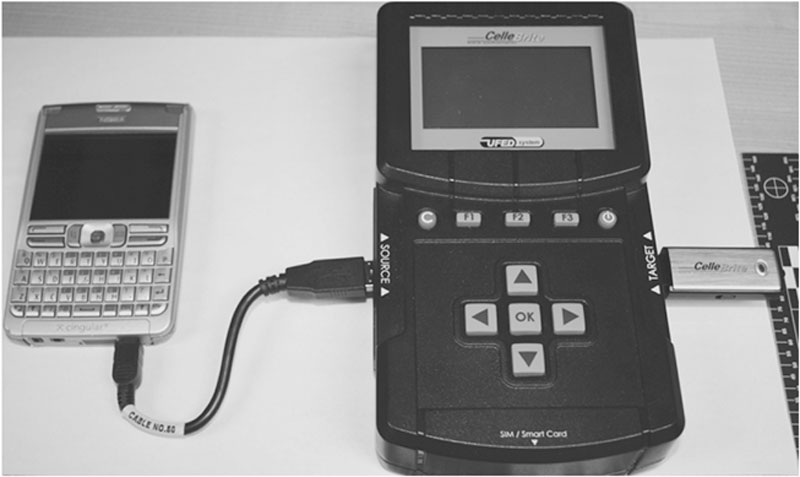

The Cellebrite Universal Forensic Extraction Device (UFED) is a stand-alone, self-contained hardware device used to extract phonebooks, images, videos, SMS, MMS, call history, and much more. It supports more than 2,500 phones and is designed to extract information at the scene. It also has a SIM card reader and cloner. As an interesting aside, Cellebrite devices (the nonforensic versions) can be found in many cell phone stores. They’re used to transfer a customer’s data from one device to another (http://www.cellebrite.com/forensic-products/forensic-products.html?loc=seg). Figure 10.3 shows a Cellebrite UFED device.

Figure 10.3 A Cellebrite UFED.

EnCase Smartphone Examiner is an EnCase tool designed to review and collect data from smartphones and tablet devices. It collects data from Blackberrys, iTune backups, and SD cards. Once the information is collected, it is easily imported into the EnCase Forensic suite for continued investigation (http://www.guidancesoftware.com/encase-smartphone-examiner.htm).

What do you do if none of these tools will retrieve the information you’re looking for? If that’s the case, it’s time to consider going “old school” and simply using a still or video camera. Although this would not be the first choice, it’s better than coming away empty-handed.

Global positioning systems

Like cell phones, a GPS can be a tremendous source of evidence. It can be used to pinpoint the location of suspects as well as the criminal acts themselves (if the device was active and in their possession at the time the crime was committed). It can also be used to show where suspects intended to go. Some GPS units can provide a great deal more evidence, including mobile phone logs, SMS messages, and images. Given these capabilities, along with large storage capacities, examining these devices is well worth the time.

The GPS was originally produced for military use but was eventually shared with everyone. There are twenty-seven GPS satellites in the GPS system. Only twenty-four are in use at a time. The remaining three are held in reserve in case one of the primary satellites goes down. A GPS receiver calculates its position through a mathematical process known as trilateration (Brian and Harris, 2011).

Not all GPS units are the same. Some are feature-rich, whereas others are pretty basic. We can separate GPS devices into four categories: simple, smart, hybrid, and connected. Simple units are designed to get users from one point to another. Most simple units can store trackpoints, waypoints, and track logs. Other features may be present depending on the make and model (LeMere, 2011).

Smart units can be broken down into automotive and USB mass storage devices. Such a unit typically has 2 GB of storage at a minimum along with an SD card. They provide the same base functionality as the simple systems. In addition, they can play MP3s, view pictures, and save favorite places.

Hybrid GPS units are feature-rich and can provide a great deal of evidence. Hybrid devices possess the same features as smart devices plus some. Most notably, these devices provide hands-free access to your mobile phones via Bluetooth. This ability to interact with the cell phone can provide a secondary source of much of the data found on the phone. This would include call logs, an address book, and the MAC address of up to ten of the last phones that have connected to the unit. Finally, Short Message Service (SMS) messages can also be recovered (LeMere, 2011).

A connected unit provides hybrid features and the ability to get real-time information, including Google searches and traffic information. These units have GSM radios along with SIM cards. This functionality is subscription-based, so we may be able to obtain the subscriber information associated with the account.

GPS data can be grouped into two categories: system data and user data. System data will provide us with trackpoints and a track log. Trackpoints are a record of where the unit has been. They are created automatically by the system. Trackpoints can’t be altered by the user. By default, the system determines the interval at which they are recorded. Users can, however, modify this setting, changing the time or distance interval. The track log is a comprehensive list of all trackpoints. This list is intended to help users retrace their path (LeMere, 2011).

Waypoints are part of the user-created data. When interpreting waypoints, you need to keep in mind what they represent. Unlike a trackpoint, waypoints don’t always indicate the physical locations where the unit has been. They can be places the user intends to visit. The user can enter these locations based on the address or the actual coordinates, or from a list of Points of Interest (POI) supplied by the GPS unit manufacturer.

GPS devices are similar in many respects to cellular phones and are handled in much the same way. They can have volatile memory that may need to be preserved. When powered on, these units are constantly interacting with the satellites. This interaction can cause complications from a forensic perspective, by potentially causing relevant evidence to be overwritten or compromising its integrity.

GPS devices are cropping up in many different places. Taxi cabs, delivery trucks, and more are frequently being outfitted with GPS units. One such example of a GPS unit assisting investigators is the case of Las Vegas dancer Debbie Flores-Narvaez. Her brutal December 2010 murder showed the value of GPS evidence. Police were able to locate her dismembered remains using GPS data from a U-Haul truck. The suspect, Jason “Blu” Griffith, apparently transported her remains in the truck and was unaware that the truck was equipped with GPS. Police obtained the GPS data and used them to retrace Griffith’s movements, leading to her body (Hartenstein and Sheridan, 2010).

Evidence in the case also included text messages. The victim’s mother, Elise Narvaez, said that her daughter sent her this text message on December 1, 2010: “In case there is ever an emergency with me, contact Blu Griffith in Vegas. My ex-boyfriend. Not my best friend” (Hartenstein and Sheridan, 2010).

Summary

Our mobile technology allows us to check e-mail, browse the Internet, plot out a road trip, and instantly access other people in our lives. Many people can’t remember when, or even imagine how, they made it through the day without their smartphones. The advent of this technology has created both sources of evidence and challenges for forensic examiners.

In Chapter 10, we covered a wide range of topics on mobile devices, particularly cellular phones and GPS units. Cell networks are comprised of several components, including base stations, Mobile Switching Centers, Visitor Location Registers, and others. There are different types of cell networks, each with their own unique characteristics. Code Division Multiple Access (CDMA), Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM), and Integrated Digitally Enhanced Network (iDEN) are the most common.

Like computers, there is more than one operating system used by cell phones. Windows Mobile, iOS, Android, and Symbian were covered in Chapter 10. Cell phones can contain vast amounts of digital evidence, including e-mail, call logs, text messages, images, videos, and more.

Records maintained by the carrier can also be valuable during an investigation, particularly the Call Detail Records (CDRs). These records can provide us with dates, times, and phone numbers, as well as the originating and terminating towers used during a call. The tower information can help us determine the general vicinity in which the phone has been used.

How cell phone evidence is collected and preserved is critically important. The first priority in dealing with any mobile device is to isolate it from the network. A powered-on device that isn’t isolated is a major problem. In this state, evidence can be changed, overwritten, or destroyed. Keep in mind that certain cell phones can be wiped remotely by the suspect or the carrier. Isolating a cell phone can be done using a Faraday bag or an arson can. While Subscriber Identity Modules or SIM cards contain data worth examining, it’s important to remember that not all phones will have them.

Global Positioning Systems (GPSs) are in wide use today and function as another source of digital evidence. There are different types of GPS, units including simple, smart, hybrid, and connected. Waypoints, trackpoints, and track logs are some of the data recorded by the units that we can use. These artifacts can tell us where the unit has been and where a user intended to go.