· 3 ·

BY EARLY 1904 Joe Patterson had taken the hint—surely numerous hints—from senior Tribune editors as to his slim chances of slipping even modestly progressive editorials into the paper. But instead of entirely backing off (as Alice begged him to do, once reminding him to “think about which side your bread is buttered on”), he only shifted tactics, now devoting his energy to producing a less overtly political and more or less consumerist supplement for the Sunday edition, which he was allowed to title the “Workingman’s Magazine”—a four-page insert featuring information and advice for white-collar office workers on such topics as “travelling tips” and “business opportunities”—which was generally well received by readers though scarcely noticed by those on high.

Then in March came a frantic summons from his mother for him to come immediately to Washington—alone, sans Alice; this was specified—to help out with a new family crisis: the wedding of his younger sister, Cissy Medill Patterson, nineteen years old, with flaming red hair, porcelain-white skin, a piquant slightly upturned nose, and the air and manner (which would stay with her all her life, for better or worse) of the proverbial “wild child.” As an older brother Joe was fond of Cissy and she of him, though neither had much in common beside the bond of siblings in a family of disordered grownups. Most emphatically she was neither populist nor progressive, nor for that matter much of anything just then beyond determined to be married to a Polish-Russian nobleman by the name of Count Josef “Gigy” Gizycki, more than twenty years her senior, handsome in the then-approved international style of brushed-back hair and waxed mustache, certifiably aristocratic with a castle in eastern Poland, many acres, peasants, horses, debts—and alas very little money—and on the whole with a persona, as one might call it, that seemed fairly to shout a warning to willful nineteen-year-old American heiresses. But Cissy was intent on becoming Countess Gizycka, and had already provoked a first crisis by making a press announcement of her own engagement. The second crisis, following rapidly from the first (and thereby causing Joe’s summons to Washington), stemmed from what might be called a contractual disagreement between the principals, which is to say between the dashing, impecunious Gigy, who expected to be paid for his services—and paid rather well—and Cissy’s parents, notably her father, the morose, moralistic Robert Patterson, who took the position that upstanding Americans neither wished to sell their daughters nor for that matter wanted to buy a son-in-law, even one with an impressively unpronounceable title.

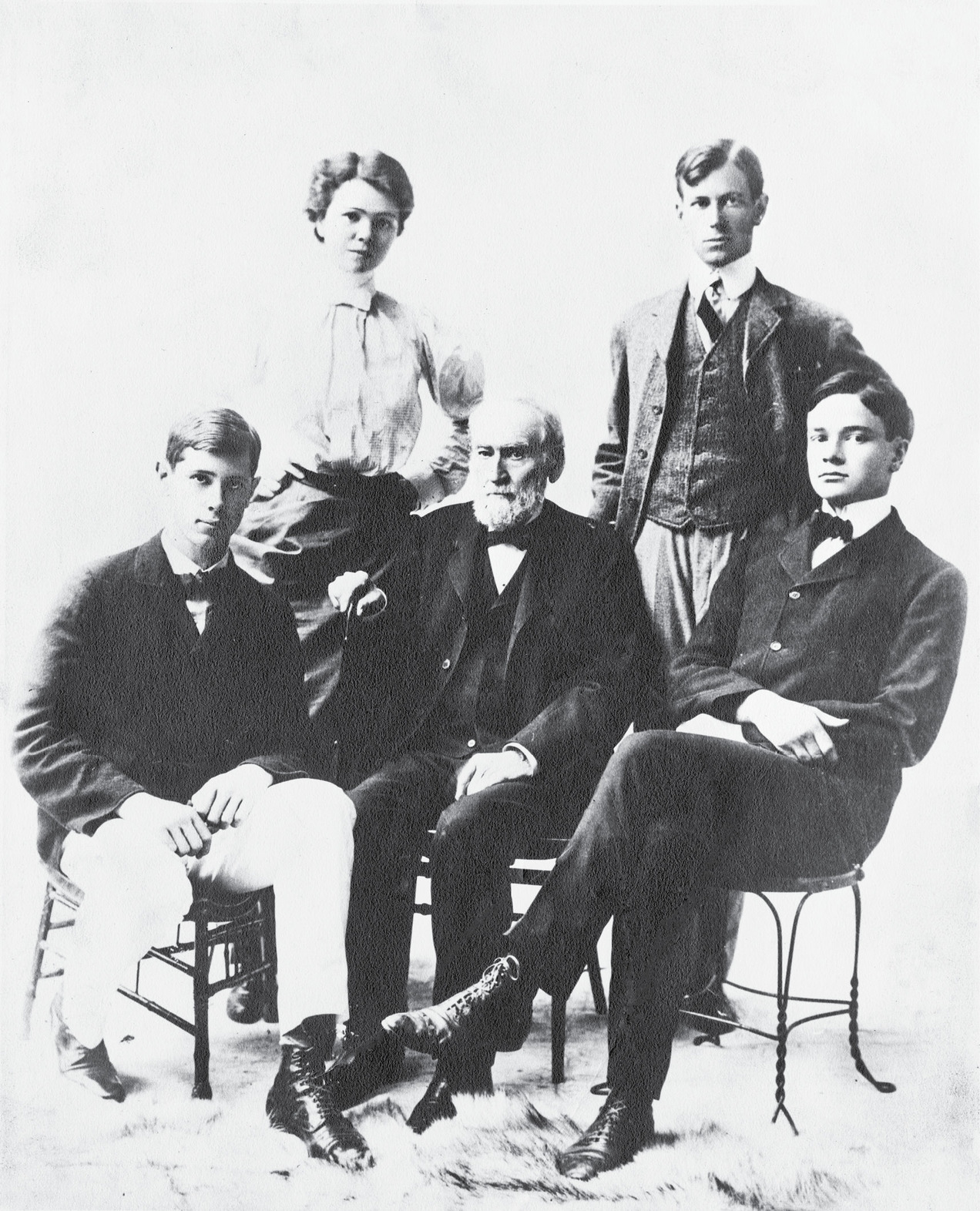

Joe Medill, founder of the Chicago Tribune, one of the original “Lincoln men,” with his grandchildren: (clockwise) Eleanor “Cissy” Patterson; Medill McCormick; Joseph Medill Patterson; Robert R. “Bertie” McCormick.

By the time Joe arrived in Washington on the morning of March 4, entering the marbled splendor of 15 Dupont Circle with a valise in one hand and a copy of the “Workingman’s Magazine” in the other (in the hope that his father might finally consent to read it), the Patterson-Gizycki nuptials were in ever-more-serious disarray. The bride was locked in her room upstairs, threatening suicide should the wedding not take place. Somewhere downstairs Nellie Patterson was attempting to placate a Roman Catholic bishop and a trio of priests who had been hastily enlisted, first to consecrate the vast secular edifice by sprinkling holy water about the premises, then to perform the ceremony—a liturgical compromise presumably between the Pattersons’ stern Protestantism and the count’s smoky Russian Orthodoxy. The father of the bride, perhaps understandably, was nowhere to be seen. The putative bridegroom himself was reported to be defiantly incommunicado a mile or so distant, behind the walls of the Russian Embassy.

Much against his will, or at least his commonsense impulses, Joe was persuaded by his mother (who seemed to have evolved a rather more flexible attitude to dowries than her husband) to take a hansom cab over to the czar’s embassy and there try to arrange a compromise with the haughty Gizycki. This too turned out to be more easily said than done. Joe Patterson, a Yale man and prince of Chicago, was accustomed to a certain high level of American sophistication and behavior. But with Count Gigy and the other Russian aristocrats gathered around him at the embassy, he quickly found himself out of his league. When Patterson showed up in the embassy billiard room, Gigy just laughed at him, and not a kindly laugh either; and when Joe, repeating the family line, told the count that in America they did things differently, Gigy snidely replied to the effect that that was why America was so provincial, so uncultivated, and so on. In the end, for better or worse, an understanding was achieved, which is to say the Pattersons gave in: A “distribution” to Count Gizycki of so many dollars was agreed on, payable in such-and-such a way, according to such-and-such a schedule. Whereupon the wedding took place. The Catholic bishop, assisted by the trio of priests, united the unlikely couple in Holy Roman matrimony; flowers, champagne, and even a wedding cake were produced. However this was still not the end of the drama, for the groom was expecting not merely the promise of future dollars but an actual here-and-now check, a down payment, so to speak. This in turn was the last straw for Robert Patterson, citizen of Chicago and the Middle West, plainspoken son of the Great Presbyterian. He wouldn’t write one; not then, not there. And so, while the new countess was upstairs changing into her traveling clothes, the newly married count turned on his heels and left for Union Station by himself, declaring that he would travel back to Europe without her. As it happened, Nellie Patterson (who already enjoyed being the mother of a countess) had a checkbook handy of her own, with an ample balance. She soon wrote out a check for ten thousand dollars, and once more prevailed on Joe to take another hurry-up hansom cab, this time to the train station, bringing with him both the check and his sister. Which he did, handing both over to his infuriating new brother-in-law and even staying around long enough to wave a sentimental American good-bye to the departing couple.

IT SHOULDN’T COME as much of a surprise that Countess Cissy’s marriage eventually ended no better than it began; rather worse, in fact, seeing that by then there was a child involved. But that, as they say, is another story for another time. Meanwhile, let us hold for a moment on Joe Patterson, now in his second-class carriage on a Baltimore & Ohio train, heading back to Chicago. As one of those young men (and surely he is still young, though fast growing older) who stoutly claimed how he always liked to learn from his experiences—well, a biographer might unprofessionally wonder what might he have lately learned? That his father’s patriarchal posture was something of a mask, that he can’t even protect himself; that his mother, another character better suited to the stage, is too tightly sewn into her own costume to be of much use to anyone else; that his sister is at once spoiled, beloved, and incorrigible; and that fancy-pants Europeans are no better than one would expect, besides being snootily unreliable witnesses to the American life he cherishes? But possibly he has known much of this already. As the train travels westward into the Pennsylvania twilight, does he stare out the grimy window? Does he read? Read what? Keep in mind, moreover, that he is not really the hero of this narrative, not the key player. In any case the key player is a she, has not been born yet, has not even been thought of, in the way such things are thought of. In the meantime he is here in this story, one might say, to provide context, a kind of ballast. And we also know this about him, because years later, so many years later, his wife (now a grandmother) remembered it: that in his suitcase, which his mother herself had packed, beneath some shirts and whatnot, still perfectly folded, clean, and crisp, lay the same copy of the “Workingman’s Journal” he had brought down and presented to his father, who had returned it to him, obivously still unread.