· 16 ·

LEDYARD SMITH was not Alicia’s only suitor, or even the most impressive, but he seemed to be cut from different and more interesting cloth than her other beaux, as people used to call them, or “young men” or “swains” and so forth. Not that he wasn’t from the same proper, prosperous Midwestern background as most of his rivals: For instance, young Daggett Harvey (of the railroad dining-car Harveys) or Sage Cowles (of the Minneapolis newspaper publishing Cowleses) or Princeton junior Adlai Stevenson (also from a newspaper publishing family, in downstate Illinois), or for that matter Smith’s fellow Yale classmate, Jim Simpson, son of the president of Marshall Field & Co., and perhaps his chief competitor. As it happened, Smith and Simpson were each fair haired, tall, athletic, both formed in the same Anglophile, Eastern prep-school mold at St. Paul’s, and friends of a sort. But where the Marshall Field heir was cool, assured, and self-contained sometimes to the point of arrogance, an unusually gifted college athlete who already played polo at an international level, Ledyard Smith was more of a warmhearted, enthusiastic outdoorsman with an adventurous spirit; an undergraduate archaeology student, he was sufficiently proficient to be heading south soon to Guatemala, on a dig among newly discovered Mayan ruins for the Carnegie expedition.

The time we are talking about is the summer of 1926, six months or so after Alicia’s coming-out party at the Blackstone. There’s a photo portrait from that period: a youthful, pretty face, though one perhaps not yet fully formed or well defined, and wearing a somewhat anomalous expression that might be described as demure or even maidenly. Given the all-too-real reputational hazards for a girl her age (nineteen and some), and in her position, of not being an actual maiden, it’s more than likely she was still intacta, as the horrible Church Latin adjective put it; but while not being a seriously “bad” girl, she was definitely not a “good” girl either. By the conservative standards of the midwest, she was probably somewhere on the near or far edge of being “fast,” as well as footloose; which is to say that, having failed her entrance exams to Bryn Mawr college, she hadn’t bothered or quite got around to applying anywhere else; and what with her father busy in New York with his ever-more-successful tabloid (and ever-more-complicated personal life), and with her mother preoccupied with Elinor, and if not Elinor then with something else, Alicia was mostly content to spin her wheels as a horse-riding society girl, going to parties, shuttling between Chicago and Libertyville, and now nearby Lake Forest, with its sporty Onwentsia Club.

Alicia, demure debutante, at her coming-out at the Blackstone Hotel, Chicago, 1925.

In July, when young Ledyard Smith disappeared into the Guatemalan jungle, “four mule-riding days from the nearest trading-post,” as he put it in an early letter, for a while he seems to have had Alicia’s mostly devoted and certainly romantic attention. More letters followed (most of which she kept all her life). For example: “Our little boat upriver was so crowded with Indians I couldn’t stand up and for once in my life I was almost glad you weren’t with me…but at last we are on our way to the Oaxtun mahogany camp, which I think will appeal to you if or when you come down.” And: “How was our child, the little dog, and what can I bring him and you from the wilds…?” And: “I love you terribly, dearest. Let me know if you love me and exactly how much you love me.” Alicia replied to these endearments with her own warm protestations of love, as well as her eagerness for life in a Central American rain forest. But the truth was, she had not grown up with many examples of constancy in her life (aside from those noble sentiments expressed in the nineteenth-century poems her father loved to recite out loud). Besides, her other suitor, the impressive Jim Simpson, was not in Guatemala but right next door, so to speak, scoring goals on the polo field of the Onwentsia Club. In early December, when Ledyard emerged from his dig, he returned to Yale, sought out Simpson at Scroll and Key (the “secret society” both men belonged to) and in a spirit of Ivy League chivalry, politely asked his rival to step aside; when neither man would give up the quest, they ended up exchanging one of those sweet, weird handshakes of bygone days, accompanied by the obligatory wish that the best man win.

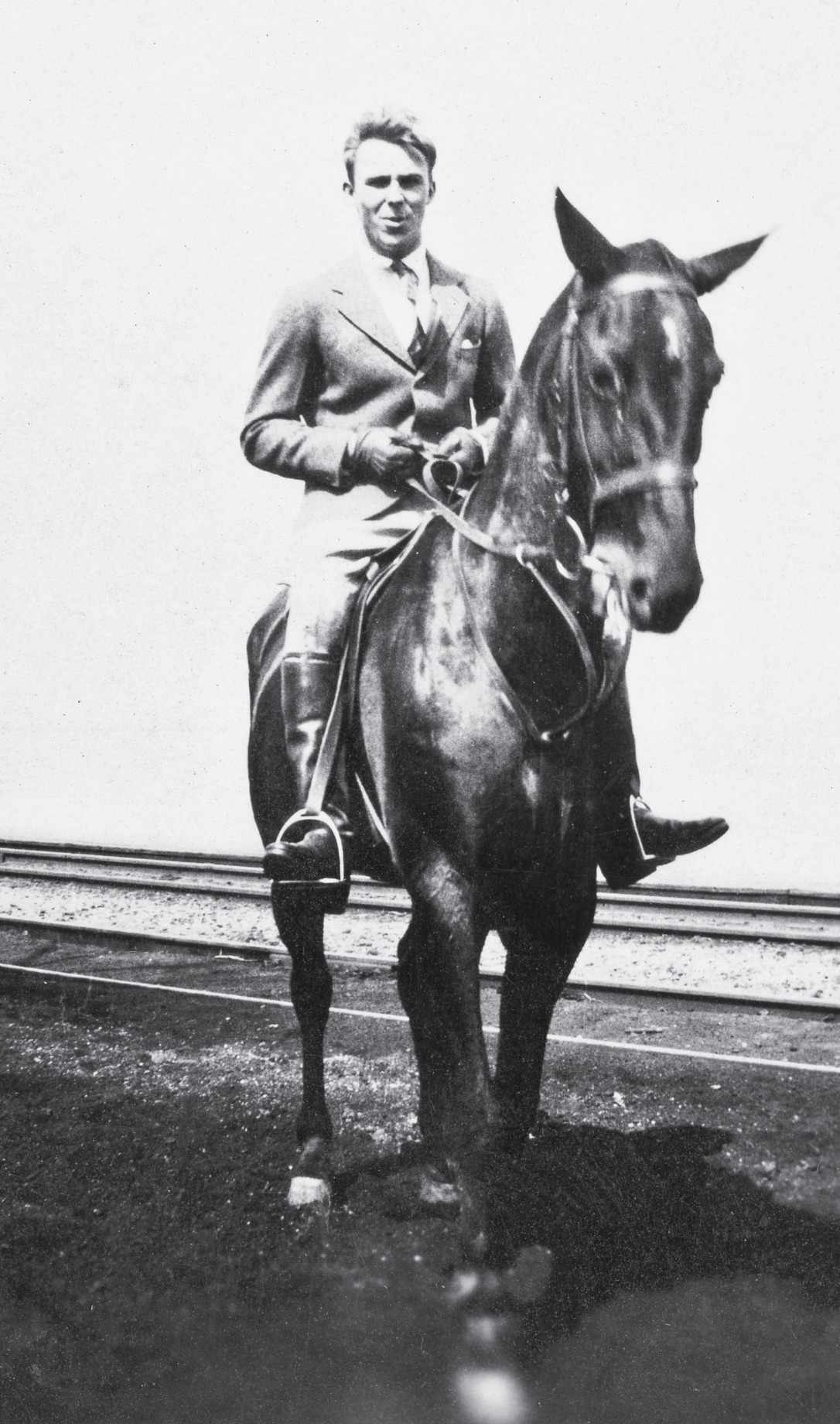

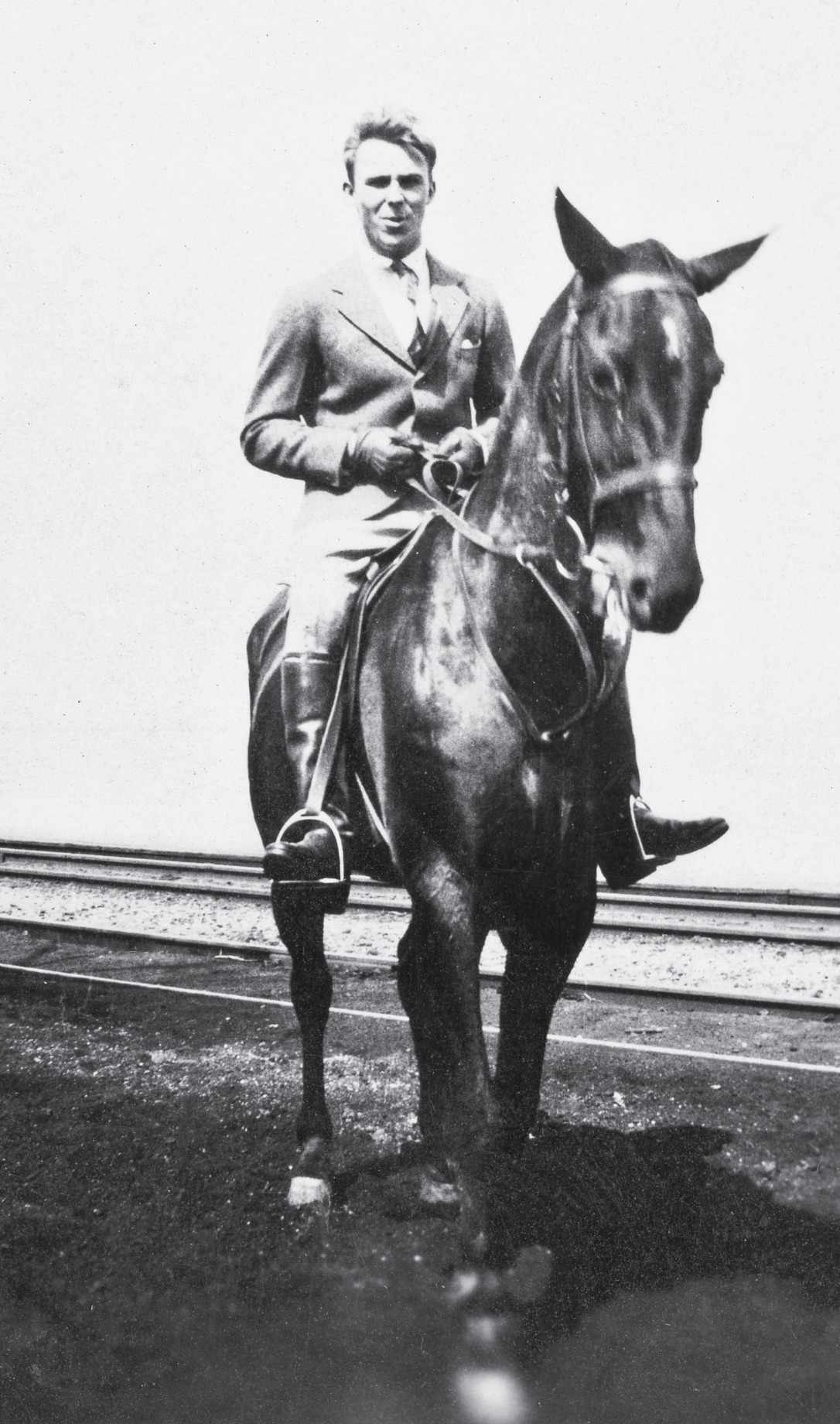

Polo-playing Jim Simpson, department store heir and Alicia’s mother’s favorite.

As for the object of all these knightly attentions, Alicia was neither especially desirous nor obviously ready to sign her life away to either boy, or man, or in fact to anyone at all. But then, in the way of large, conveniently faraway planets that suddenly change course and inconveniently start looming closer, both her parents, each in his or her own way, apparently decided to take an interest. First, her father, after returning unexpectedly to Libertyville one too many times and finding his daughter still out in the middle of the night, “driving around,” decided to bring her to New York, install her in a room in his apartment, and give her a low-level reporting job on the Daily News. This interesting experiment lasted three months, more or less, with Alicia by no means unwilling to run errands or trot around, notebook in hand, taking notes for the society page; in the end it largely foundered on young Miss Patterson’s chronic though cheerful confusion as to where exactly she was supposed to be, and when, and such details as, for example, who was it she had just interviewed? Meanwhile, back in Illinois her mother had been pursuing a different and altogether more ambitious strategy. This being a time when parents were fond, in thought and practice, of “settling down” their children by marrying them off, Alice Patterson had several businesslike conferences, or chats, with Mr. and Mrs. Simpson, and together they came to the sound conclusion that the best thing for young Jim and Alicia would be to make their evidently close friendship legal.

When Alicia first got wind of the maternal push for a Simpson marriage, she was still in New York, still corresponding with the distant, beguiling Ledyard, and was distinctly cool to the idea. “I really don’t think I want to marry Jim, now or ever,” she wrote her sister Josephine. “Please don’t tell mother because I know they’ll [sic] be a complete explosion when she finds out.” But by June 1927 she was back on the Libertyville farm, unceremoniously bounced from her job on the Daily News, personally fired by none other than her pompous uncle Bert McCormick (since the war now preferring to be known as Colonel McCormick, or just “the Colonel”), feeling isolated and sorry for herself, and in a mood to agree to an August wedding to Simpson. At which point Ledyard Smith reappeared, on a two-week leave from his Guatemala excavations, first looking for his beloved in New York, next pursuing her to Libertyville, where, catching her in a different mood, he apparently persuaded Alicia instead to fly the coop with him, back to his tent in the jungle.

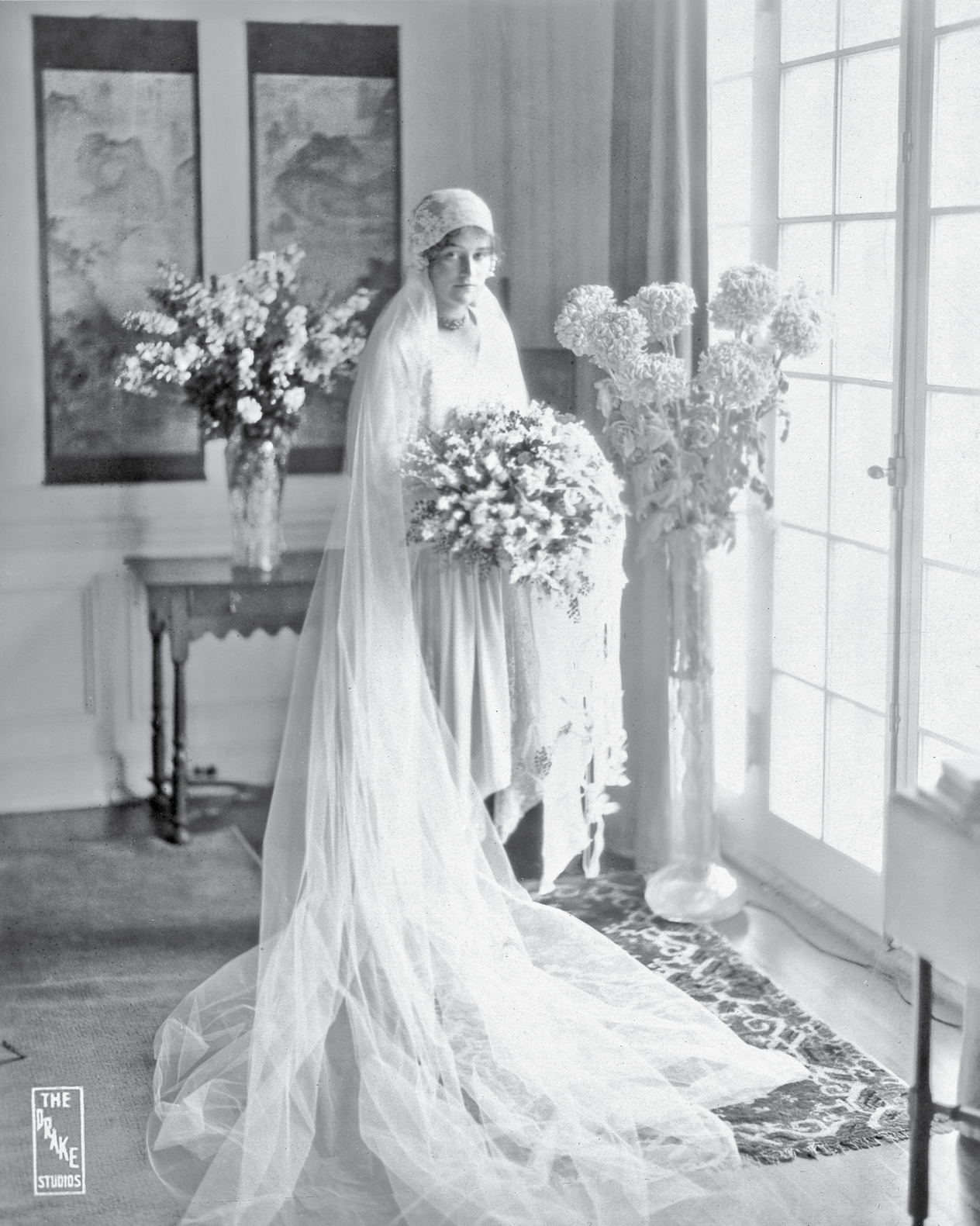

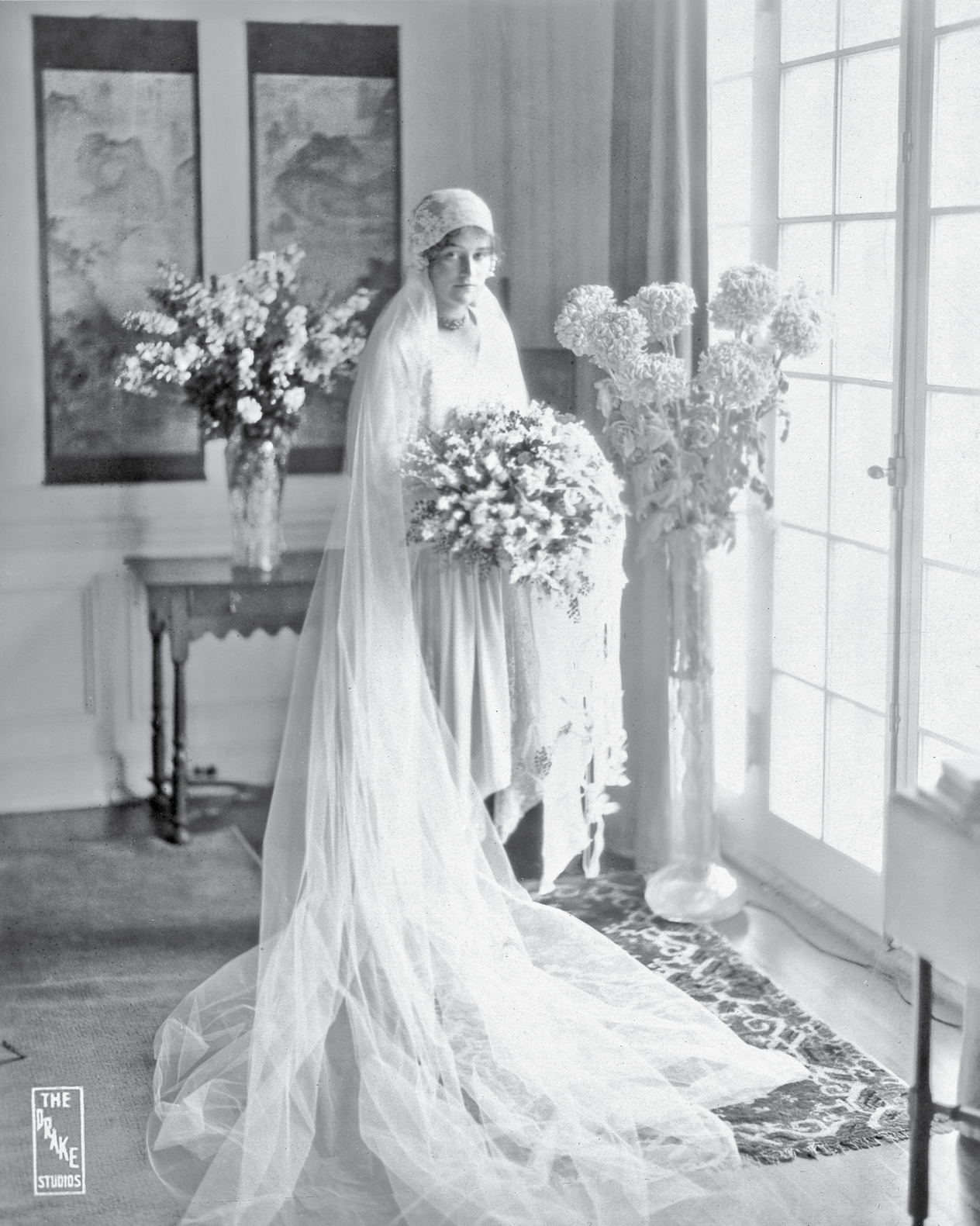

Alicia in white satin and lace before her Lake Forest wedding to Jim Simpson, 1927.

Some of what ensued sounds today like a scene, or several scenes, from one of the romantic comedies of that era. For instance, in the Boston Herald, August 19, 1927: “Society Girl Betrothed to One Man, as Another Gets License to Wed Her.” From the New York Times of the same day: “Mr. Ledyard Smith, a young archaeologist with the Carnegie Expedition, explained that he had been in a hopeful and romantic mood” when apparently all by himself he had obtained a marriage license in Waukegan, Illinois (a town notorious for overnight marriage licenses), somehow “unaware that his intended was already engaged to another.” Perhaps a better exegesis of this odd tale was that Alice Patterson, on being tipped off about her daughter’s escape with Ledyard to the marriage-mills of Waukegan, had quickly sprung into action: first calling in her chips among Chicago’s society reporters so as to announce her errant daughter’s retroactive engagement to Simpson, and then browbeating her not-quite-ex-husband to send out a similar story to newspapers across the country.

The bride and groom, with (left) sister Josephine, as noted in the Chicago Evening American.

Faced with this force-majeure countermove, Alicia folded and returned to Libertyville, while poor Ledyard fled the scene, still trying to explain to sardonic reporters how, or why, a man might take out a wedding license on his own, returning to the safety of the Guatemalan mahogany forest. (NOTE: It’s worth mentioning that Ledyard Smith stayed the course in archaeology, in due course becoming Professor Ledyard Smith, and eventually chairman of Yale University’s preeminent Department of Archaeology, where by the end of a long and distinguished career he had been recognized as one of the pioneers in the excavation and interpreting of the great archipelago of Mayan ruins that runs south from Mexico into Central America.) Two days later the recent runaway bride, her face now swollen by tears and a bad case of hives, accompanied her mother to dinner with her future Simpson in-laws at their Tudor villa in suburban Glencoe. And five weeks later Alicia Patterson and James Simpson, Jr., were duly married, at a small, mostly private ceremony in the former Patterson farmhouse in Libertyville (by now convincingly transformed into a Georgian mansion), with the ruddy-cheeked, very Episcopal rector of St. Paul’s School officiating, and the scion of a rival Chicago department store as best man. The lovely Elinor, now Mrs. Russell Codman, had been designated matron of honor but called in sick at the last moment. Uncle Bertie McCormick, recent terminator of Alicia’s journalism career and copublisher of the Tribune, arrived in a maroon Rolls-Royce, with three bodyguards to protect him from what he called “new business competition” by the Chicago mob. For doubtless many reasons, the bride, who had seemed surprisingly self-possessed throughout the service, burst into loud sobs at its conclusion, and couldn’t or wouldn’t stop crying for long minutes, though apparently quieting down enough to whisper loudly to her father to the effect that, while she may have agreed to a wedding, her intention was to stay married to Simpson for only one year, no less but no more.

Once a farmhouse, the Patterson house in Libertyville, Illinois, early winter.