· 31 ·

BY ALL ACCOUNTS the happiest times in the Brookses’ mostly disconnected marriage were those long days, usually in late August, which they spent together at his fishing camp, in the wilderness along the east fork of the Ausable River, about sixty miles north of Lake Placid, in the shadow of Mount Marcy; a stretch of the river where forbidding boulders, brush-covered banks, cold water, and plentiful crayfish provided three species of trout—brook, brown, and rainbow—with what many aficionados thought was the best natural habitat in the eastern United States. Joe Brooks’s camp had well-sited tents, employed the best camp cook in the Adirondacks, and Brooks himself, despite his size and enormous hands, was widely held in high regard for his impressive river skills. He famously used a two-ounce bamboo rod, specially made for him by Leonard & Co., so extraordinarily light that a clumsy cast could break it, and yet sufficiently precise that a superior fisherman could drop a fly just where he intended, at the edge of the most seemingly inaccessible pool, and then delicately float the fly along the surface until a rising fish took it, at which point he’d reel him in, slowly, patiently, sure of his touch—like a great saxophone player, one of his guests once said, holding an impossible note.

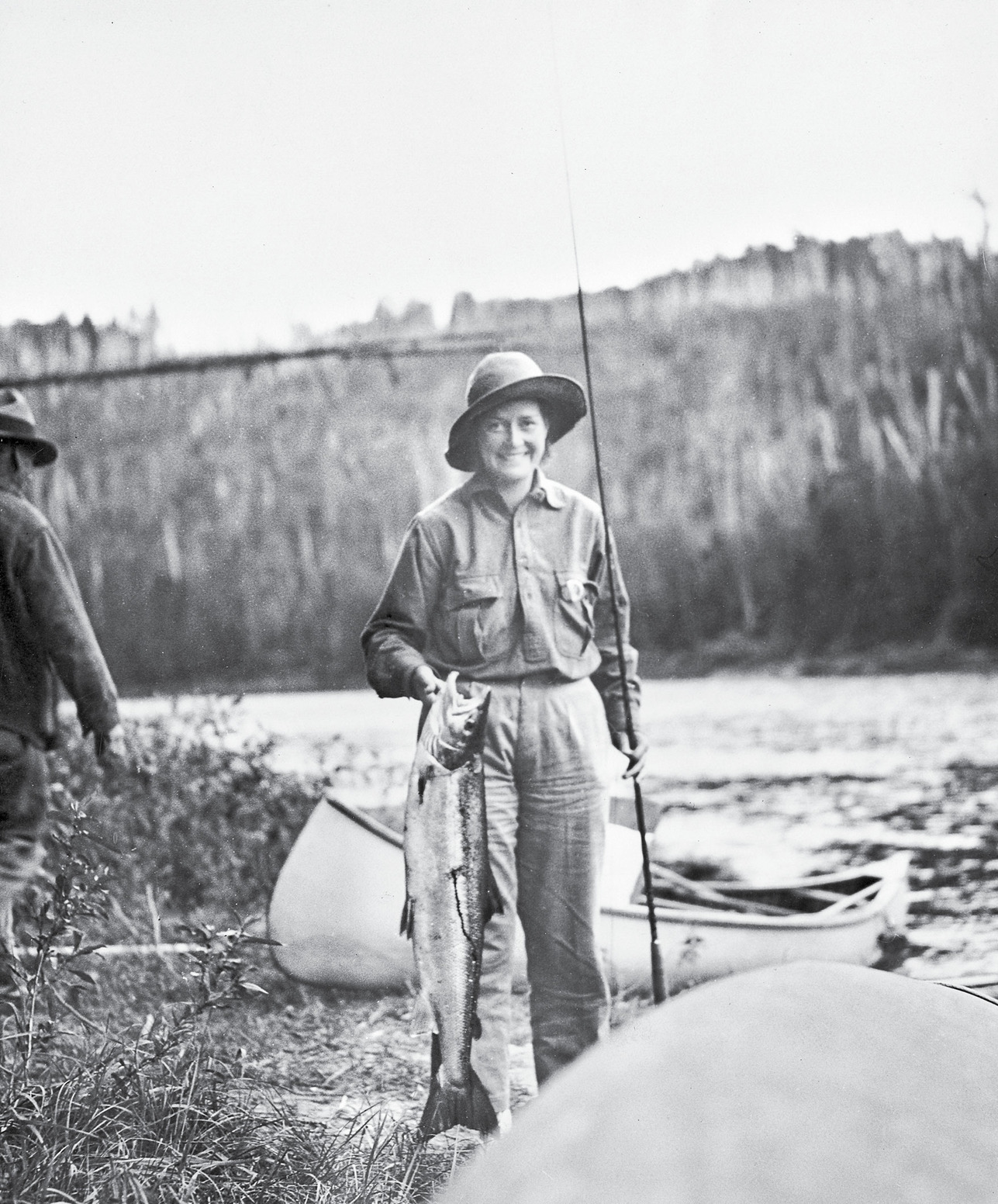

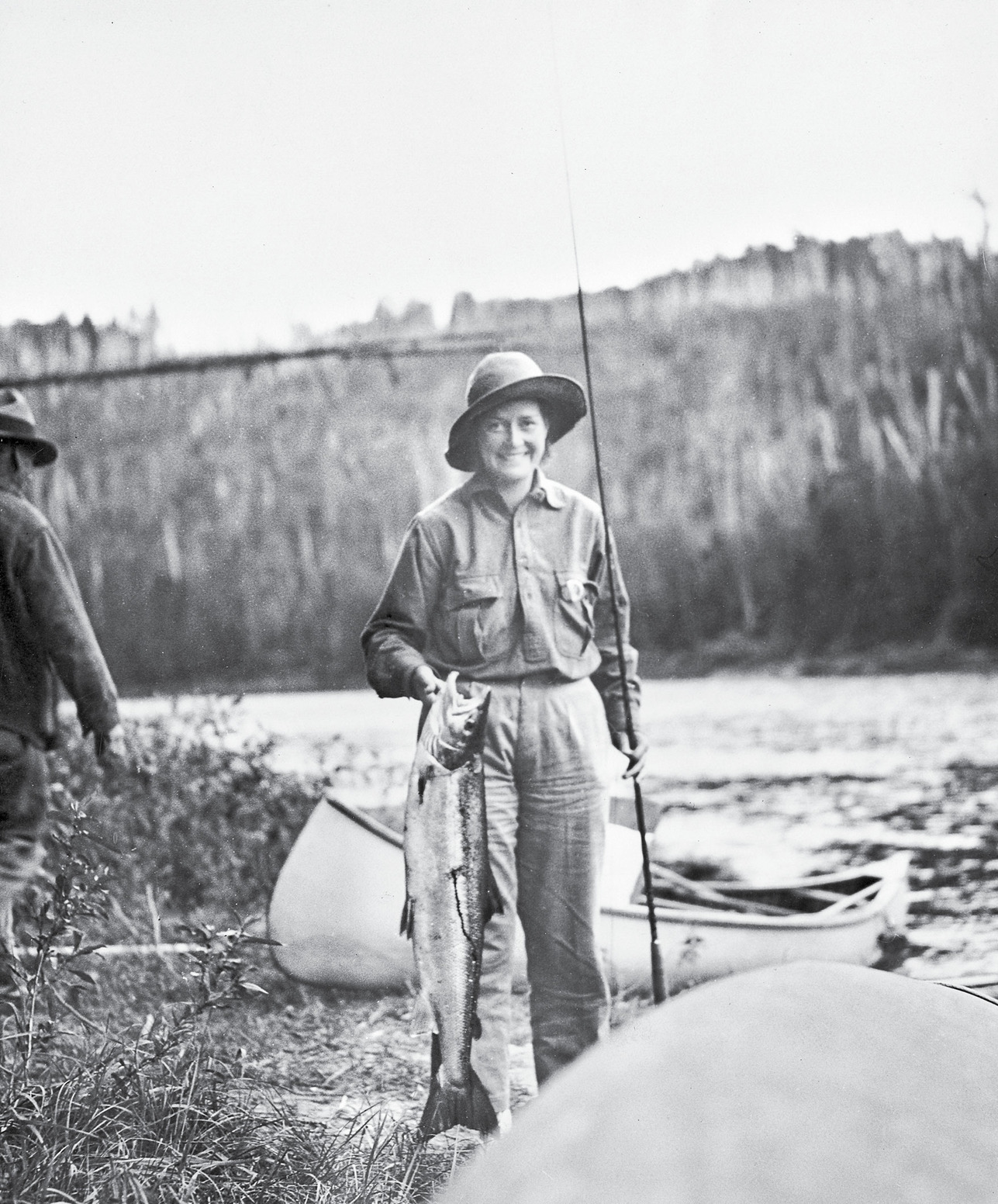

While Alicia hadn’t originally come to fishing with the natural hand-eye coordination commonly required for expert fly casting, and in the beginning often got her line hung up on shrubs or overhanging tree branches, or sometimes lost her footing on slippery rocks and took a ride downstream (with consequent fits and curses), all the same she characteristically refused to give up trying, with the result that year by year she improved, until she herself was now at an almost expert level, successfully wielding the special three-and-a-quarter-ounce rod Joe Brooks had doggedly taught her to use. As he more than once told her sister Josephine, his idea of perfect happiness was to watch his wife working the river on a late summer afternoon; it was, he used to say, as much as he wanted out of life, which was doubtless true.

Fishing on the Ausable in the Adirondacks.

Brooks and Alicia owned a single-engine Cessna together, at least that’s how they described it (a gift naturally from Joe Patterson), which they mostly used for flying in and out of fishing camp; also, toward the end of August, after a couple of weeks of living in tents, they’d sometimes stuff some proper resort clothes into a couple of valises, take off from the field outside the village of Ausable Forks where they parked the plane, and fly two hours south to the old-fashioned but thriving town of Saratoga Springs, New York, originally popular for its healing, medicinal waters, and now even more so for its August season of thoroughbred racing.

Despite its out-of-the-way, upstate location, Saratoga was an unexpectedly cosmopolitan place, where you could gamble legally on horse races, or illegally at the several casinos on the other side of the lake, where well-known big bands played, and Hollywood celebrities such as Bing Crosby and Clark Gable mingled with the Eastern racing elite. Alicia and Joe usually stayed at the United States Hotel, one of the older and better hotels, which had been around since the 1890s, when Commodore Vanderbilt’s New York Central had helped make the town an attractive destination. Even in the late 1930s, Saratoga seemed to belong to a bygone era, with American flags and patriotic bunting on display, horse-drawn carriages competing with automobiles, dry-goods stores and soda fountains and a long dusty avenue called Broadway. The rich men who owned thoroughbred stables elsewhere in the country, and sent their horses by rail to Saratoga, walked about in linen suits and straw hats; their ladies sat in private boxes at the track, shaded places where “colored” butlers served mint juleps and Sazeracs, and changed their dresses throughout the day depending on hour or mood. August at Saratoga with its muted, well-bred atmosphere of carnival, drew “the best people” from all over the country, from Newport, Bar Harbor, Philadelphia, and certainly many from Long Island’s North Shore: Phippses, Whitneys, Vanderbilts, and Bostwicks. Not surprisingly, in that week of late August 1938 Harry Guggenheim was there too; he almost always went up there for the season, as Alicia almost surely knew he would.

A few more words about Mr. Guggenheim. At the time he was forty-eight years old and a man of many attributes. For one thing, in an era when there were fewer than one hundred millionaires in the nation, he was immensely rich: the grandson of Meyer Guggenheim, an immigrant whose silver mine in Leadville, Colorado, began the family’s mineral empire; the only son of Daniel Guggenheim, one of seven brothers who expanded the original silver business into copper mines and smelters across the American West and into South America. For another thing he was highly intelligent, both practically inquisitive as well as erudite. Privately tutored for years at home to protect him from anti-Semitism, he had enrolled at Yale, but soon after arriving at college he noted that he was refused permission even to try out for the freshman tennis squad despite his strong qualifications, and promptly left New Haven, along with his manservant, enrolling in Cambridge University across the Atlantic, where he distinguished himself in engineering studies and also won his tennis “blue.” Later he worked as an engineer and project manager at the family’s mines in Peru and Chile. In his late twenties he served as a distinguished United States ambassador to Cuba from 1929 to 1932. By the time he and Alicia made their initial connection, he had become a substantial power in the world of aviation, first as an early friend and patron of the still hallowed Charles Lindbergh (Lindbergh had written We, the famous account of his transatlantic flight, in a guest room at Falaise), and more recently as director of the important Guggenheim Fund for the Promotion of Aerodynamics. In his spare time (so to speak) he had also developed a growing interest in thoroughbred racing, deploying part of his North Shore acreage for stables and raising horses, several of which were now up in Saratoga for the races, along with their owner, who gave every appearance of being a bachelor, and a rather debonair bachelor at that, but was in fact still married to his second wife, Carol Morton, a member of the Morton Salt family, by report a kindly, nature-loving alcoholic who increasingly kept to her own world, emotionally as well as geographically.

Of course Alicia Patterson Brooks was also still married, in some ways even more married than Harry Guggenheim, since her husband was right there with her in Saratoga, although for the most part not so much with her as around the lake at the casinos. Joe Brooks had never been much of a horse fancier except for the betting part, but Alicia loved horses, always had; even though she no longer rode as an avocation, she still knew her way around stables and trainers, was known to other horse people, and during those four or five days in August it appeared that she was fast becoming known to Harry Guggenheim, who asked her to view the races with him from his private box at the track, which she did on numerous afternoons. Then, too, she began getting up early, leaving her sleeping husband in their bed at the United States Hotel for a brisk walk to the racetrack, where she stood beside Harry Guggenheim while he watched his horses work out, timed their runs, conferred with his trainer. One morning after the workouts, she remembered, he asked her to meet him later in the day, at the afternoon auction, when he said he would be bidding on some of the yearlings and would value her opinion. Tipton’s Auction House was the oldest in the country, a big, dusty, barnlike structure out near the racecourse, with a small auditorium, a rectangular walking arena for the horses, and a pavilion for special guests. Alicia, who had been short of feeling special lately, seems to have felt herself a special guest of Harry Guggenheim’s and later, after the bidding was over, in the course of which he’d flattered her by taking her advice on several offers, they took a walk outside, down by the New York Central tracks, past the empty boxcars for the horses, past the siding where they parked the owners’ private railroad cars. She remembered, or claimed to remember, that Harry had on a dove-gray linen suit with a yellow tie; she thought she carried a straw hat in her hand because the wind was blowing; and when he took her by the arm to help her across one of the tracks, something she could easily do by herself, his hand just under the elbow, the lightest of touches but still something so definite, she knew there was going to be a lot more to it than that.