TWELVE

Papa Woojums

For more than a decade alcohol and parties had been Van Vechten’s means of escape from the mundane realities of life. It seemed to him, surrounded by youth and gaiety, and with a belly full of booze, as if he need never grow up or grow old but forever remain the wide-eyed adventurer he had been when he arrived in New York in 1906. With the convergence of illness, bereavement, economic crisis, and the passing of his literary career, the pretense became impossible to maintain. To stay fresh, young, and vital, he would have to reinvent himself as he had done so many times before.

The initial phase of his latest transformation took place in the seat of an airplane in the fall of 1931. Van Vechten had long harbored an ambition to fly. Air travel was bound to be of interest to him: a cutting-edge adventure accessible to only a special few. He gasped at the exploits of the great early aviators, especially Charles Lindbergh, whose bravery as much as his celebrity fascinated him. Van Vechten took his first plane trip in October of 1931, when he flew to Richmond, Virginia, and found the experience exhilarating. In flight he was able to perform feats he had previously managed only in a metaphorical sense: racing at remarkable speed high above the humdrum lives of the earthbound; risking life and limb in search of a new thrill. The moment he landed he telegrammed Marinoff about it and wrote excitedly to friends to tell them that he had now joined the ranks of the airborne. In an interview she gave to a New York newspaper a few months later, Marinoff confirmed that her husband “tinkers with planes, flies in them to everywhere, and all the time,” adding that this new passion of his was infinitely preferable to his last. “I have tasted all the drinks in all the speakeasies … and I am tired of them. I have memories of hundreds of parties in apartments, in nightclubs, in Harlem, in the Village. It was a phase in the life of this generation. It was very hollow. I never liked it,” she said, the last utterance perhaps a trifle disingenuous.

Aside from experiencing the thrill of his maiden flight, there had been another motivation for traveling to Richmond that fall. In July his friend Hunter Stagg had put him in touch with Mark Lutz, an idealistic thirty-year-old journalist on The Richmond News Leader who added a refreshing, youthful presence to the town’s aging literary scene. Lutz had been on vacation in New York that summer and was hopeful of meeting Van Vechten, a man he had heard much about yet never encountered in the flesh. Van Vechten too was intent on getting acquainted, for Lutz was one of the young men about whom Stagg wrote gossipy letters during long, hot Virginian afternoons when he should have been working. As early as 1926 Stagg mentioned Lutz in response to Van Vechten’s teasing that Richmond lacked any attractive young men. “Taylor Crump is good-looking,” Stagg protested, “and Berkley Williams, and in a way, Mark Lutz. So there.” When they first spoke, Van Vechten suggested Lutz come to a gathering he was hosting at his apartment. Already having plans for the evening, Lutz attempted to politely decline the invitation, but Van Vechten was insistent: whatever other engagements he had could be arranged for another time; a party at the Van Vechtens’ was not something anybody in Manhattan could afford to miss. Lutz had no choice but to relent, his diffident southern manners no match for Van Vechten’s Manhattan high-handedness.

Just as Donald Angus had been, Lutz was attracted to Van Vechten for his worldliness, his self-confidence, and his sophistication. Van Vechten was never interested in anyone who played hard to get, and in some measure he surely took to Lutz because the young man was fascinated by him. Yet Lutz was not the frolicsome gadfly that Angus had been when they met, and he was certainly no debauchee. He was a more sedate companion for a less frenzied period of Van Vechten’s life. In one of his notebooks Van Vechten pondered the things that made Lutz interesting. Most unlike his own profligate ways, Lutz was cautious, parsimonious even, and a nonsmoking teetotaler. He was also highly superstitious, believed himself to have psychic powers, and followed peculiar rules, such as never swatting flies in airplanes, an act that seemed to him a tiny perversion of the laws of nature. What they did have in common was an interest in the plight of African-Americans and their culture. As a liberal-minded journalist from Virginia, Lutz was always seeking out examples of the brutalities of segregation and worked to expose them in his work if and when he could. At the time of their first meeting, in July 1931, the infamous Scottsboro Boys trial, in which eight young black men were sentenced to death for the alleged rapes of two white women in Alabama, had just concluded, and Lutz fiercely backed the campaign to get the convictions overturned. Pressure groups and organized campaigns were not Van Vechten’s thing, but he did put Lutz in touch with Langston Hughes, who was heavily involved in the matter and had spoken out publicly about the injustice of the trial.

By the start of 1932 Van Vechten and Lutz were engaged in a love affair of the deepest intimacy. When they were not together as, because of the great distances that often separated them, was frequently, they sent each other letters, postcards, and clippings from newspapers and magazines almost every day for the next three decades. In his will Lutz requested that Van Vechten’s letters to him, perhaps as many as ten thousand, be destroyed after his death, but Van Vechten seemingly kept every piece of mail he had received from Lutz. In them all subjects are raised: from family bereavements, to international diplomacy, to rows with work colleagues, to race relations, reflecting the extent to which each was involved in the other’s life. “It was disappointing to have NO word from you in the mail of yesterday,” Lutz wrote on one of the rare occasions he found his mailbox empty one morning. More than a decade into their relationship he spelled out exactly how important Van Vechten had been to him from their first meeting in 1931. Before then, he said, he had played the field, but meeting Van Vechten had changed him: “I settled down to ONE … and would not change it for a MILLUN.”

At almost exactly the same moment that he found a new lover Van Vechten discovered the artistic calling he had been seeking. His friend Miguel Covarrubias had recently returned from Europe with a marvelous gadget, a new Leica camera that was lightweight and portable, yet capable of taking exceptionally crisp pictures. Photography was not new to Van Vechten. His relationship with the art laced its way through his life, usually in close concert with his valorization of the famous. As a child he lived among his stage idols through their cigarette card photographs and placed friends in dramatic poses before the family’s box camera. At the Times he recorded his association with opera stars through photographs. Being photographed himself by Nickolas Muray, one of New York’s most fashionable photographers during the 1920s, was an important moment to him, confirmation of his celebrity status. Photography to Van Vechten was a quintessential modern art, combining technology, spectacle, and glamour, though the cost of equipment and the time commitment involved in perfecting a technique had never permitted him to be anything other than an occasional practitioner. As Covarrubias demonstrated, the Leica allowed the amateur a freedom and a degree of precision previously unimagined. Always an early adopter of technology, and eager to test himself in a new element, Van Vechten soon bought one for himself. He turned unused space in the apartment into a makeshift darkroom and studio, and by January 1932 the new hobby was becoming a full-time obsession. Van Vechten roped in Mark Lutz to help him in his early shoots. Lutz set up lights and posed in front of the lens, allowing Van Vechten to experiment and learn from his mistakes. When Lutz was unavailable, other members of the jeunes gens assortis were employed to lend a hand, notably Donald Angus, and the artist Prentiss Taylor, who on “bright winter Saturdays” accompanied him on shoots in Harlem as well as a trip to Copenhagen in upstate New York to photograph the gravestones of Van Vechten antecedents long since dead.

Despite the amateur setup, Van Vechten was convinced from the start that the gift of taking a good photograph, and in particular a good portrait, was his. “Great photographers are born, not educated,” he believed, and if not great quite yet, he suspected it was only a matter of time. As early as February 1932 he boasted to Gertrude Stein that Stieglitz had pledged to hold an exhibition of his work and told Max Ewing that he was struggling to decide whether his first show would be photographs of Harlem or portraits of the great and good. Stieglitz never hosted a Van Vechten exhibition and almost certainly would not have offered one to such a novice. Probably Van Vechten’s bulletproof ego decided that he deserved an exhibition mounted by the godfather of American photography, and that was what counted. The facts, again, were irrelevant to his sense of truth. By June he was even comparing his capabilities, favorably, to those of Stieglitz’s when he sent Mabel Dodge some examples of his work, including a self-portrait. These, he declared, were just a taste of his considerable talent.

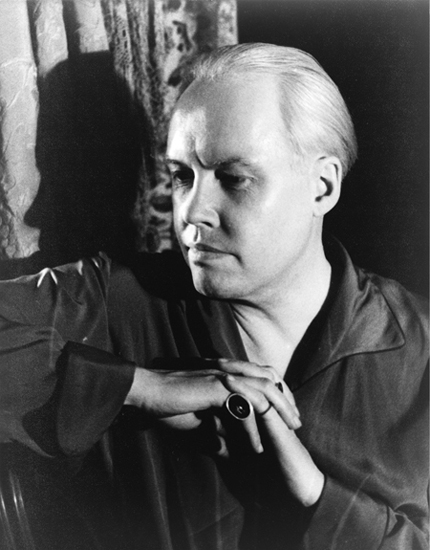

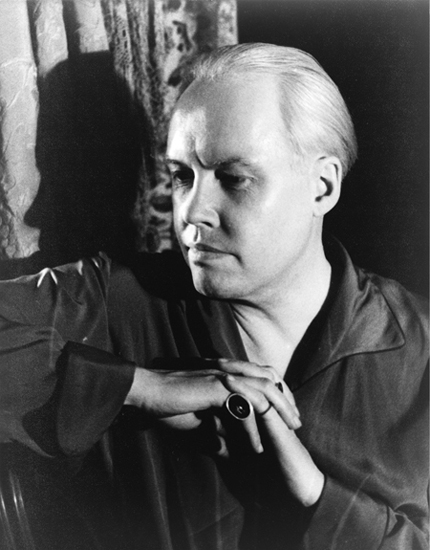

Carl Van Vechten, self-portrait, c. 1934

In truth, the photographs he took in the early 1930s were of wildly varying quality. Many were enchanting, but many others poorly lit, peculiarly composed, or spoiled by fussy backgrounds that seem more a reflection of the photographer’s taste than the sitter’s personality. It is the number and range of his sitters that are extraordinary. “My first subject was Anna May Wong,” he often claimed, “and my second was Eugene O’Neill.” Though that was not strictly so, it was a trademark Van Vechten embellishment in that it articulates a general truth, in this case the volume of celebrated people who sat in front of his camera. In addition to Wong and O’Neill, Bill Robinson, Langston Hughes, Bennett Cerf, Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, Henri Matisse, Gladys Bentley, George Gershwin, Lois Moran, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Charles Demuth, to name but a few, all were shot within roughly the first year of his photographic career. Scattered among the artists and impresarios were various interesting people outside the public eye. Over the years Marinoff posed endless times, of course, and usually in some extravagant costume: a belle epoque society lady; a flamenco dancer; resplendent in an Indian sari. Numerous other relatives were captured, as were favored domestic servants, window cleaners, doormen, and Sarah Victor, the pastry chef at the Algonquin Hotel. Even Harry Glyn, a bootlegger and pimp whose services Van Vechten had used on occasion over the years, was summoned for a shoot.

Anna May Wong, c. 1932, photograph by Carl Van Vechten

The discipline of portrait photography was tailor-made for Van Vechten. It indulged not only his voyeurism but also his fascination with exceptional people and the immense pleasure he took in being in their company. It was no coincidence, either, that photography seized him at a point in his life when change was taking place all around him and outside his control: the deaths of friends and loved ones, the economic situation that transformed New York’s social world, and the end of his writing career. With photography the holder of the camera had complete power; moments in time could be frozen forever. Van Vechten discovered that he was able to dictate the entire process of producing a photograph from beginning to end. The one variable was the attitude of his subjects, but he soon found that he was able to rely on his ebullient charm to get from them exactly what he wanted.

At Apartment 7D his shooting space was small and quickly became hot under the studio lights. In coming years he moved to larger premises, but in all his studios there was a closeness, an atmosphere of emotional intimacy. All around lay the clutter of Van Vechten’s props and backdrops—crumpled sheets of colored cellophane, posters, rugs, African sculptures, floral wallpaper. To the sitters who arrived this was clearly neither an artist’s workroom nor the studio of a commercial artist but the den of an obsessive hobbyist. Observing him at work at close quarters for many years, Mark Lutz believed Van Vechten’s greatest attribute as a photographer had nothing to do with technical expertise or artistic flair but rather with his ability to put people at their ease, that silky charisma he had first used to get stories and photographs as a Chicago journalist. An arm placed lightly across the shoulder and some rich encomiums would do the trick for most. Even when a high-profile movie star came for a session, Van Vechten was unfazed: “a few glasses of champagne and he or she would pose contently and without self-consciousness,” Lutz recalled. Once things felt suitably loose, Van Vechten would position his subject and photograph quickly “in about a twentieth of a second” before self-consciousness arrived to spoil the moment. Occasionally, it would take considerably more effort. When Billie Holiday came for a shoot in 1949, Van Vechten struggled for two hours to break through her contrary, sullen exterior. It was only when he retrieved some shots he had taken of Bessie Smith, Holiday’s great heroine, that she let her guard down. “She began to cry, and I took photographs of her crying, which nobody else had done,” he remembered; “later I took pictures of her laughing.” Holiday ended up staying until five in the morning, telling Van Vechten and Marinoff her life story, and Van Vechten thought it one of his finest moments, a devastating combination of his charm and artistic skill used to capture an American icon. “There are no good photographs of Holiday except the ones I took of her,” he said a year after her death.

Financially secure, Van Vechten had the freedom to pick and choose his subjects and never had to compromise for the sake of meeting a commission or appealing to a particular audience. He refused to sell his work too and only ever gave away prints or permitted them to be reproduced as a personal favor. That degree of autonomy allowed him to produce an enormous portfolio of work strikingly different from any other major American photographer of the era. The 1930s marked the start of a golden age of photojournalism in the United States, with magazines such as Life and Sports Illustrated giving photographers the opportunity to share their work with millions, bridging the gap between the artistic tradition of Stieglitz and Steichen and the functional mass-market photography that appeared in popular newspapers. The New Deal also freed up millions of dollars for government bodies such as the Farm Security Administration to fund the work of Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, Louise Rosskam, and other social documentarian photographers whose work fell somewhere between art and journalism as they captured an ailing rural and small-town United States colliding with the forces of modernization. Van Vechten existed entirely outside the social documentarian tradition, yet he used much of the same vocabulary to describe his work, insisting that the purpose of his photography was also “documentary.” He saw it as his mission to document a different America, one of modernity and sophistication that he had seen develop over the last three decades, inhabited not by the average folks of the nation’s heartland but by a cosmopolitan breed iridescent with talent and personal magnetism. In the fantasia of his studio the outside world evaporated; the Depression, the New Deal, and all the other facts of 1930s America ceased to exist. Nothing remained but the individual and the act of self-expression.

In that sense Van Vechten’s photographs were a fluid continuation of his novels. His gaze through the camera was that of an elitist; his concern was to immortalize outstanding individuals, the brilliant and the beautiful. His rigid individualism kicked against the trend he discerned among many young artists of the 1930s for politicizing their work with leftist dogma. When Langston Hughes sent him Good Morning, Revolution, a collection of his latest poems that was as staunchly ideological as the title suggests, Van Vechten was dismayed. “The revolutionary poems seem very weak to me,” he wrote Hughes, who at that point was traveling the Soviet Union. “I mean very weak on the lyric side. I think in ten years, whatever the social outcome, you will be ashamed of these.” Of course Hughes’s political views were his own concern, he said, but he worried that in servicing them in his poetry, he had sacrificed his individuality, the essence of his genius. He urged him to abandon this new direction and rediscover the warmth and personality of his earlier work. “Ask yourself … Have I written a poem or a revolutionary tract?” As if to underline his own commitment to the cause of individual expression, he concluded the letter by letting Hughes know that “I am still taking photographs: Better than ever.”

As far as Van Vechten was concerned, politics, especially the politics of the left, could only corrupt or dilute individual character and was therefore antithetical to art. A half dozen years later he summed up his position when he wrote his friend Noël Sullivan about Paul Robeson’s growing attraction to socialism, at which he was equally appalled. Politics in all systems and irrespective of ideological persuasion, he informed Sullivan, is nothing more than a game played by megalomaniacs. For those who want to change the world the best they can do is to lead by example and invest their energies in self-development, because ultimately “the only person one can improve is oneself.” Even the rise of fascism in Europe could not rouse him to take an interest in politics. On March 7, 1934, Marinoff went with Lawrence Langner and Armina Marshall to join twenty thousand other spectators at Madison Square Garden, to watch a mock trial of Adolf Hitler put on by the American Jewish Congress. As a proud Jew herself Marinoff was eager to attend and acutely concerned about the situation in Germany. But Van Vechten chose to spend the evening indoors, exercising his Promethean powers in the darkroom, creating his own tiny universe populated by talented and fascinating souls, untouched by the complications of the real world.

* * *

It might be a stretch to say that Van Vechten was now living a quiet and healthy life, but it was certainly a world away from the self-destruction of the late twenties. His drinking was under control, and the constant business of taking and developing photographs provided a diversion from temptation. He also made frequent trips to a health resort at Briarcliff Lodge in Westchester County under the supervision of Dr. William Hay, a naturopath whose regimen of vegetarian diets and colonic irrigation was a popular fad with the Van Vechtens and many of their friends in the early thirties.

The bond with Marinoff remained intact but no less fraught. When they were together, they sniped and bickered constantly, and when apart, they pined for each other. Marinoff, now semiretired and with fewer grand projects than Van Vechten to keep her occupied, suffered bouts of tremendous loneliness and anxiety. She spent a good deal of time with Eugene and Carlotta O’Neill at their home in Georgia, silently studying their mutual dependency, at times envying the tranquillity and normality of their relationship compared with her own peculiar marriage. She was delighted that debauchery had finally relaxed its grip on Van Vechten, though she often felt excluded by his new obsessions with air travel and photography, activities he chose to practice in the company of the young and beautiful, as if their vitality would seep into his pictures. In the summer of 1933 Van Vechten left Marinoff behind and flew out for a grand tour of the West with Mark Lutz, photographing him at every new place they visited: at the Grand Canyon; in Chinatown, San Francisco; on the beach in Malibu; outside Mabel Dodge’s home in Taos. Vacations in London, Paris, Amsterdam, Genoa, Barcelona, Madrid, Valencia, Mallorca, Marrakech, and Casablanca all followed soon after, with Van Vechten rekindling acquaintances along the way and taking more pictures of new subjects, Joan Miró and Salvador Dali included. As was invariably the case with Van Vechten’s closest male companions, Lutz quickly became a dear friend of Marinoff’s. Their adoration of the same man gave them common ground on which to meet, but Marinoff also used the friendship as a means of maintaining a romantic closeness to her husband. In the past she had been able to accommodate Van Vechten’s affairs with relative ease, perhaps because her busy and successful career as an actress had given her opportunities to express herself independently of Van Vechten. Now, without a career to invest in, she could not help feeling the time that Van Vechten devoted to his young men and his photographs was an act of rejection and abandonment. Van Vechten behaved as if oblivious that his new fixations were causing Marinoff upset. He was once again lost in self-interest; the fulfillment of his wishes took precedence over all else, including the health of his marriage. Even on December 31, 1935, when Marinoff hoped they might see out the year together by sharing lunch in their apartment, Van Vechten refused, saying he was too busy in the darkroom across the hallway to spare her an hour of his time.

His obsession with photography was total. Wherever he went he captured the world with his Leica. Even if he was walking ten blocks to meet a friend, the camera went with him in case he saw something enchanting in a department store window or was struck by the beautiful face of a waitress or a group of laughing children playing on a street corner. The old collecting instincts were channeled into a new medium, striving to capture and contain the gaiety of life in its innumerable tiny manifestations. It was another thread that connected Van Vechten the photographer to his previous iterations as novelist, essayist, critic, and reporter. A young Lincoln Kirstein joined the periphery of the jeunes gens assortis in the early 1930s and said Van Vechten’s commitment to “elegance in the ordinary” provided vital inspiration for his own work with George Balanchine that led to the establishment of the School of American Ballet in Connecticut in 1934 and in time to the New York City Ballet. It was through Van Vechten, Kirstein said, that he “first saw an American ballet had to have more to do with sport and jazz than czars and ballerinas.”

Kirstein also impressed Van Vechten, who said Kirstein’s work as a patron of the arts in New York was as important as the activities of the great Renaissance princes of Italy. Young, handsome, charismatic, wealthy, and gay, Kirstein was almost the Platonic ideal of a Van Vechten photographic subject, and Van Vechten took some excellent portraits of him that drew out much of Kirstein’s ambition and intense complexity. The best of these were shot in 1933, by which time Van Vechten had already compiled an impressive gallery of America’s key artistic figures. But at the center of Van Vechten’s catalog of excellence there was one gaping hole: Gertrude Stein. Since the end of the 1931 he had sent Stein repeated evidence of his camera skills in the form of postcard prints, but by the fall of 1933 he had yet to shoot her. He was desperate to do so and to have Stein recognize his prowess as a portrait artist. In May 1933 he pleaded with her to come to the United States, where he would photograph both her and Alice Toklas, promising that she would be overjoyed at the results. “I do nothing but make photographs now and they are good.” With Steinesque repetition he included passages virtually identical to those in letters to her throughout 1932 and 1933. His persistence was partially motivated by a nagging sense that in recent years his place in Stein’s court had been diminished. In 1914, when he wrote “How to Read Gertrude Stein” for The Trend and secured the publication of Tender Buttons, he was unrivaled as Stein’s leading American supporter. In the interim, others had moved her profile forward. In 1923 Jo Davidson enshrined her as Buddha in his famous statue, and Man Ray photographed her extensively throughout that decade. Robert McAlmon risked financial ruin in 1925 by publishing Making of Americans, a book that Van Vechten had failed to publish through Knopf, and most recently Edmund Wilson dedicated a whole chapter to Stein in his highly acclaimed book on American literature Axel’s Castle. The encroachment of these figures on territory he had staked out during the First World War stirred his natural feelings of covetousness.

His friendship with Stein was never in jeopardy. Ernest Hemingway had it right when he said that Stein “only gave real loyalty to people who were inferior to her.” There is no question that Stein thought Van Vechten fitted into that category, unthreatening and biddable. Though they had corresponded avidly for twenty years, Stein showed minimal interest in Van Vechten’s writing, which she thought entertaining but not true literature, especially not his bestselling novels. From any other friend Van Vechten would not have tolerated such open indifference to his achievements. From Stein he accepted it unquestioningly. He still regarded her as the brightest star in his galaxy of brilliant people; being a member of her inner circle was proof enough for him that she recognized his specialness. What grated him was the prospect that the wider world might not appreciate the closeness of their bond.

When Stein registered a literary hit in the United States during the summer of 1933, Van Vechten felt both elated for her success and bitterly jealous that he had played no direct part in it. The work that catapulted Stein into the mainstream was The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. The book, ostensibly the life story of Stein’s partner, was filled with juicy gossip about the European and American stars of the Left Bank, giving an inside look at the years of artistic foment before, during, and after the war. Written in a much more accessible style than her previous efforts, it was such a critical and commercial success that Time made Stein its cover star in September 1933, confirmation that she was at last a mainstream literary phenomenon. It was a huge moment for Stein and her supporters, a vindication of their persistent support. Van Vechten was bothered that the photograph used on the magazine’s front cover was not taken by him, but by the twenty-seven-year-old George Platt Lynes, Stein’s new favorite boy. A few weeks after the Time cover, Van Vechten wrote Stein pressing his credentials once again, hoping for some praise in return. Seeing other photographers’ shots of her gave him “a tinge of jealousy,” he said, with an almost audible pout. “You’ve seen very few pictures taken by me. When you do, I think you’ll be very surprised.” Physically unable to contain his desire to bind his name to her success, when he wrote Stein about an introduction he had been asked to write for a reprint of her book Three Lives, he referred to it pointedly as “OUR Three Lives.” Bursting to gain some public recognition for Stein’s sudden ascension, Van Vechten espied the perfect opportunity when Four Saints in Three Acts, an opera with an all-black cast, written by Stein and the composer Virgil Thomson, made its premiere in Hartford, Connecticut, on February 7, 1934.

He arrived at the opening night in the mode of Stein’s official representative. “I am getting very excited,” Stein wrote him from Paris two days before the premiere, saying she was glad that Van Vechten would be acting as her eyes and ears. It was a role Van Vechten took with conspicuous seriousness. Before the curtains parted, he stalked up and down the aisles of the auditorium three times, surveying the scene as if conducting some vital task, making a mental list of all the celebrated people in attendance, and allowing his own presence to be known. Eventually he took his seat for one of the most extraordinary nights at the theater he had ever experienced.

The performance began with a near-empty stage and a drumroll. Slowly the saints made their entrance, and the scene was infused with color. Black men and women in tunics and robes of red, blue, purple, yellow, and green filled the stage, assembling themselves in shapes, fusing, then separating. The setting was supposed to be medieval Spain, but it was clear from the beginning that this was a world detached from geography and history, existing nowhere but in the imaginations of its creators. At one point seminaked angels dressed in loincloths danced the Charleston. Tinsel habits, golden halos, and cellophane roses drifted in and out of sight. The audience was baffled but transfixed. Every word of Stein’s libretto was carefully enunciated—“pigeons on the grass alas”; “Leave later gaily the troubadour plays his guitar”—but its meaning floated off high over the heads of the those in the auditorium, as freely as helium balloons released into fresh air. When the curtain came down, there was rapturous applause.

To Van Vechten and many others in the audience this had been more than a gripping night at the theater: it was the fulfillment of a prophecy; a colloquial, multiethnic spectacle of color and unconventionality that could only have been produced in the United States and written by their great messianic figure. “I haven’t seen a crowd more excited since Sacre du Printemps,” Van Vechten wrote Stein the following day. For twenty years he had been making allusions to the audience reaction at that historic production, but this occasion merited the comparison more than any other. Henry-Russell Hitchcock, for example, was apparently so overcome at the finale that he ran up and down the aisle, tearing wildly at his fine-tailored evening clothes, while others were left gasping in tears.

Within twenty-four hours Van Vechten had written an introduction for the libretto, which Random House would publish before the month was out. In it he told the story of how Four Saints in Three Acts came to be and found himself a place at the heart of the narrative. He let his readers know that it was at his apartment that Virgil Thomson had given the opera its first American performance back in 1929. More significantly, he also implied that it was his influence that gave Thomson the idea to cast black actors because it was he who had taken Thomson to a performance of Run, Little Chillun, a choral play with an African-American cast, at the Lyric Theatre in 1933—though Thomson maintained his inspiration was derived from elsewhere. When the opera opened on Broadway soon after, Van Vechten similarly ensured that his name was associated with the occasion, the point at which American high modernism punched through to the mainstream. For the program he reprised his role as a gatekeeper to Stein’s work with an introductory article entitled “How I Listen to Four Saints in Three Acts,” echoing his first Stein apologia, “How to Read Gertrude Stein,” written twenty-one years earlier.

The work that Van Vechten had done years ago in promoting Stein as a musical artist whose prose should be valued for its sound rather than its meaning was vindicated with Four Saints in Three Acts. But now that she was a bestseller and a Broadway hit, his old role of intermediary between Stein and a bewildered and hostile American public seemed redundant. To remain relevant to her cult, he had to adopt a new strategy. That summer he headed for France to take Stein’s picture for the first time. He photographed her as if this would be his one and only chance to do so, shooting several dozen frames in a range of poses and backgrounds at her home in Bilignin: reclining on a deck chair; petting her dogs; sitting on a garden wall with Toklas. The sheer volume of pictures he took suggests he was here to imprison memories rather than make art, to “document,” as he would say. None of the images were particularly satisfying and certainly no better than the ones taken by Man Ray and George Platt Lynes, the two photographers he was keen to displace as Stein’s favorites. He was less technically skilled than either of them, and outside the tightly controlled environment of his studio Van Vechten’s photography often appears generic and amateurish, the personality of his subjects diffusing into the ether. While at Bilignin, however, he did press his belief that the time was ripe for Stein to return to the United States. With her on his home turf he was sure he would be able to achieve something remarkable.

Stein arrived in New York on October 24 for a short lecture series, one that Van Vechten had helped arrange. Having worked so long for public recognition, Stein felt unusually vulnerable on this return from exile, frightened that audiences would be unsympathetic. As Van Vechten had suspected it would be, the tour was actually an immense success. What had originally been planned as a fleeting promotional visit turned into an epic seven-month homecoming parade. Without Van Vechten’s assistance, it might have been very different. He nursed and encouraged Stein through her early lectures, building her confidence and dispelling her nerves. On her first night back in the country she dined at his apartment, where he delighted her with copies of the New York papers, her arrival splashed across them all. A few days later, to help her prepare for her first lecture, “Plays and What They Are,” at the Museum of Modern Art, Van Vechten arranged for a test run in front of a small sympathetic audience in Manhattan, held at the apartment of Elizabeth Alexander, a friend of Prentiss Taylor’s and the widow of the painter John W. Alexander. A week after that, on November 7, Stein and Toklas took their first airplane ride when they flew from New York to Chicago to see a performance of Four Saints in Three Acts. Van Vechten joined them, promising to hold their hands should they get scared.

He was once again working behind the scenes to secure success, as he had for Robeson, Hughes, Firbank, and so many others. And as always, he ensured that his name was tightly bound to the artist he was promoting. Before he escorted Stein and Toklas on their flight to Chicago, he alerted the press to the photo opportunity and posed proudly in the frame next to the couple as they climbed aboard. He also distributed one of the photographs that he had taken of Stein in France to promote her lectures. The scholar Tirza True Latimer perceptively notes that the picture he chose was a close re-creation of the George Platt Lynes photograph that Time had put on its cover—Stein’s profile as she gazed across rural France—his way of blotting out the presence of a rival.

Naturally, Van Vechten photographed Stein obsessively, taking her portrait whenever he had the chance. In Virginia he photographed her before monuments and grand architectural forms, including the Jefferson Rotunda. Some of them could be mistaken for the sorts of holiday snaps habitually taken in front of the Eiffel Tower or Big Ben, but it seems there was an agreed plan between Stein and Van Vechten to use these photographs as a means of rooting her in American history, making her epic and durable. On receiving the Virginia photographs, Stein composed a letter of fulsome thanks in which she suggested they collaborate on a “pictorial history” of the United States. Stein would write the text, Van Vechten would supply the photographs, and “we will all be so happy.”

Gertrude Stein, January 4, 1935, photograph by Carl Van Vechten

Stein in fact was already happy. Not since Oscar Wilde’s triumphant tour of 1882 had a writer generated such excitement by traveling the nation; no American literary figure other than Mark Twain had delivered so many enthusiastically received lectures. To recognize Van Vechten’s prominent role in her triumphant return, Stein allowed their relationship to take on a new aspect, reflecting her gratitude for all the work he had done on her behalf. Among them, Van Vechten, Stein, and Toklas created a fictitious family unit called the Woojumses, the name adapted from a cocktail that Van Vechten had invented for Parties. Van Vechten became the organizing patriarch, Papa Woojums; Toklas, the nurturing Mama Woojums; Stein was Baby Woojums, the brilliant but vulnerable child who must be indulged, protected, and controlled in equal parts. He relished being Stein’s paternal guardian and gatekeeper. A matter of weeks into the tour Van Vechten wrote to Mabel Dodge to warn her that the chances of Stein’s being able to visit Taos were slim to none, so great were the demands on Gertrude’s time. Mabel was cut to the quick by the snub; Van Vechten, more than a little gratified to have got one over on his former mentor. When Stein slipped out of his grasp and went to stay with a lesser acolyte, Thornton Wilder, in Chicago, Van Vechten wrote her a letter of mock protest. “Thornton Wilder has got me down with jealousy. Don’t go and like him BETTER, PLEASE!” The tone was jokey, but the feelings of jealousy were entirely real.

Carl Van Vechten and Gertrude Stein aboard the SS Champlain as Stein waves farewell to the United States, May 4, 1935

Shortly before she left, Stein returned to Van Vechten’s apartment for a final photo session. From the studio wall Van Vechten hung a crumpled Stars and Stripes, looking at first glance as if billowing in a strong wind. In front of the flag he posed Stein and took what is perhaps the definitive image of her. With her thick, solid frame statuesque and her gaze strong and steady, she looks like a female addition to Mount Rushmore. The symbolism was not remotely accidental. Gertrude Stein was no longer a figure of ridicule but a national treasure, and the cultural forces she represented were now recognized as integral to the American experience as were the Model T and the Marx Brothers’ movies. Stein liked the photograph so much that she chose it as the front cover of her book Lectures in America. “I always wanted to be historical, almost from a baby on,” Stein admitted shortly before her death. Thanks to Van Vechten’s portrait that ambition and sense of mission were immortalized, the image intricately bound up with the public perception of Stein as an American great, a unique genius who set the United States on a new path. It was exactly how Van Vechten thought of her. He may not have been as technically slick as Lynes, Man Ray, Cecil Beaton, or the other giants of photography who took Stein’s portrait, but he had an instinctive understanding of the medium’s power to exploit symbolism and communicate myth, the mightiest weapons in the modernist arsenal. Stein was the first American artist whose reputation he affected in this way, but there would be many more to follow, from Scott Fitzgerald to Ella Fitzgerald. When he died, he ensured that his photographs would continue to embed themselves within public consciousness, bequeathing thousands of prints to institutions across the United States. On almost all of them the words PHOTOGRAPH BY CARL VAN VECHTEN are clearly embossed on the bottom of the image, his name indivisible from the artist in shot.

* * *

On May 4, 1935, Van Vechten accompanied Stein and Toklas aboard the SS Champlain. Their tour at its end, the couple returned to France with heavy hearts, nervous that yet another hideous conflict was brewing in Europe and sad to leave behind a country that felt more like home than when they had lived there. On the gangplank, journalists bombarded Stein with questions about her final thoughts on America. “It is violent and gentle,” she said. Despite all the casual brutality of the modern world, Americans had managed to preserve the kernel of innocence that had defined them in the days of her youth before skyscrapers and airplanes and nightclubs arrived. That “their gentleness has persisted while they have been becoming sophisticated,” she declared, “shows that it is genuine.” The front-page picture that accompanied Stein’s farewell messages showed the lady smiling joyously, waving her famous cap in the air with her left hand. Standing next to her is Papa Woojums, his teeth deliberately hidden from the cameras with a tight-lipped half smile, while the little finger on his left hand hooked gently into Baby’s coat pocket. It was a sign to those watching of his importance to the woman by his side, who was now a pillar of the establishment, but the gesture also displayed his enormous affection for a friend, a cause, and a fellow iconoclast. Moments later he said his goodbyes and disembarked, heading back into the embrace of the New York night, satisfied that no matter the distance between them, he and Stein would be forever entwined in their mutual legacies.