SEVEN

What One Is Forced by Nature to Do

When carnage on the Western Front gave way to a shell-shocked peace in November 1918, the Old World rocked on its haunches, its vaunted civilization dreadfully tarnished. Across the Atlantic, the United States entered a decade of unprecedented self-confidence. Mass-production industries from textiles to automobiles fueled a consumerist boom, banishing the unpleasant memories of wartime and providing a renewed sense of national mission. In the cities, New York in particular, there emerged a youthful culture of instant gratification in which American fashions, technologies, music, and movies were preferred to those of Europe. “It was an age of miracles, it was an age of art, it was an age of excess,” wrote F. Scott Fitzgerald, summing up the sense of liberation that swept through his generation. “We were the most powerful nation. Who could tell us any longer what was fashionable and what was fun?”

Not that all young Americans were seduced. To some, this was no emancipation, merely enslavement to old conventions concealed beneath garish distractions. Considering themselves outcasts within their homeland, a small cohort of literary tyros—a “lost generation,” according to Gertrude Stein—headed to Europe in search of solemn purpose. “A young man had no future in this country of hypocrisy and repression” is how Malcolm Cowley recalled the sentiment that drove him and his clique to the Left Bank and beyond during the twenties. “He should take ship for Europe where people know how to live,” where art and intellectual freedom were prized. As a middle-aged man who had long ago experienced his European rites of passage, and for whom the war, in which he had not fought, had precipitated the most creatively satisfying years of his life to date, Van Vechten did not share the disaffection of many of the clever young men who had come of age against the backdrop of industrialized slaughter. Certainly, he despaired at the provincialism and puritanism he still detected at the heart of the nation’s culture, but as the 1920s began, he could not have agreed with Cowley’s idea that Americans simply did not know “how to live.” With every passing year New York’s cosmopolitan luster seemed to shine more radiantly; living had never been such fun for Carl.

Into this life of gaiety and promise arrived a new companion who encapsulated the youthful giddiness of the moment. Blessed with soft, conventional good looks—full, plum lips and innocent doe eyes—Donald Angus arrived at the Block Beautiful one afternoon in 1919. The excitable nineteen-year-old fop of a boy was eager to meet the man whose writings on the opera and the ballet had charmed him with their arch wit. Van Vechten was keen to meet Angus too. Their introduction had been facilitated by Philip Bartholomae, a successful playwright, Broadway producer, and irrepressible gadabout with whom Angus had briefly been romantically involved. Such introductions were a key means by which Van Vechten met potential new lovers, safer than cruising and less irksome than going through the elaborate pickup rituals. When Van Vechten answered the door to Angus that afternoon, it was probably in his mind that this meeting would lead to more than a conversation about books.

Many decades later Angus still clearly remembered his first time inside the Van Vechtens’ apartment. His eyes were drawn to the clutter of oriental trinkets and the rich scarlet paper studded with gold dots that covered the walls, most striking in such a small apartment. Following his own advice about eschewing interior decorators and their notions of good taste, Van Vechten had hung that wallpaper during one of Marinoff’s working absences. On numerous occasions throughout their marriage she returned from a trip away to find the furniture rearranged, sometimes new curtains in place and whole rooms redecorated. This time his impatience to transform the living room meant he had decided to paper around the furniture rather than go to the effort of moving tables and chairs. Slapdash though the decoration may have been, to Angus the interior of 151 East Nineteenth Street matched the bohemian elegance of its celebrated residents. For at least part of the afternoon Marinoff was also there, and even though Angus was hardly an innocent, the couple was wonderfully glamorous to him. Van Vechten found Angus instantly attractive, the kind of sunny, high-spirited, and effeminate boy that he liked best. As they talked and drank, Angus felt Van Vechten’s gaze crawling across him, sizing him up with a penetrating stare, at once both warmly playful and coldly scrutinizing. For women, and for some men he knew to be gay, Van Vechten had an intense greeting ritual. For several unsmiling seconds he looked steadily into their eyes, often gripping one of their hands between both of his, the way a charismatic preacher might with a member of his congregation. It made some people understandably uncomfortable. Angus was one of those who loved being the sole focus of Van Vechten’s attention, feeling as though nothing in the world mattered more in those few seconds than the connection between him and the remarkable man opposite.

When Marinoff left the apartment for a theater engagement, Van Vechten took Angus to one of his favorite Village hangouts for dinner and drinks. Almost immediately after that first encounter a physically and emotionally intimate affair began; it lasted for one intense year before drifting into a more casual arrangement for the remainder of the twenties. It was an important relationship for them both. Approaching forty, “Carlo” was no longer able to play the neophyte in search of a knowing teacher, as he had with Gertrude Stein, Mabel Dodge, and various others. Instead he would give to Angus what they had given him, an education in how to live, lending him books to read, playing him phonograph records, and even arranging jobs for him with publishers and theater producers. In return Angus offered youth, beauty, and an outlet for Van Vechten’s need to instruct, lead, and be admired.

It is difficult to know precisely what Marinoff thought of her husband’s new relationship, which was his most involved with another man since they had met. Letters between Carl and Fania from this period betray the same affectionate mutual dependency they had always done, though the sexual passion of their early correspondence had evaporated, as it had in their domestic life. There were no more descriptions of the physical yearnings each experienced in the other’s absence, only their unwavering love and their need for companionship. Van Vechten still called Marinoff his baby, but he no longer told her how he wanted to cover her naked body in kisses, and Tom-Tom was never mentioned at all. Bruce Kellner, the same friend of Van Vechten’s who suggested in his memoirs that Anna Snyder may have given up a baby for adoption in 1907, speculates that the cause of this change in the Van Vechtens’ marriage may have been that Marinoff had also fallen pregnant and given the baby up for adoption during the last year or so. Central to Kellner’s speculation is one strange postscript in a letter Marinoff wrote Van Vechten in September 1918 that makes pointed reference to “Baby Van Vechten.”

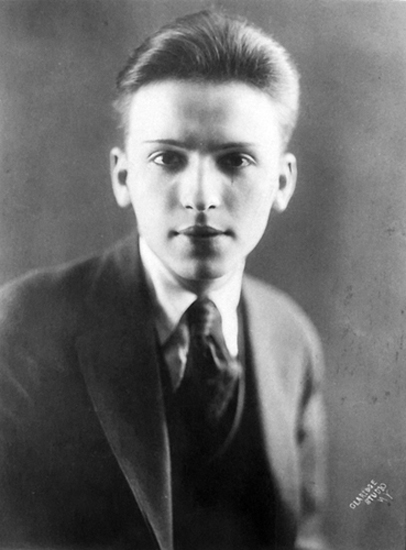

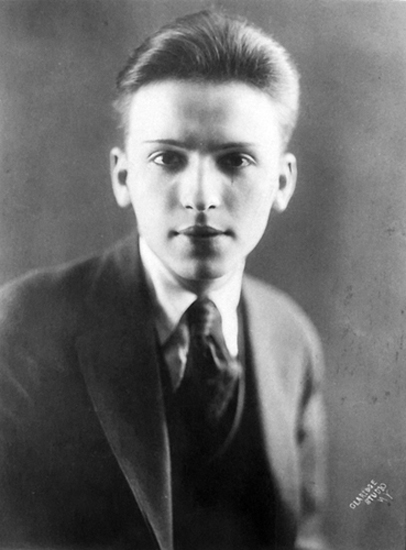

Donald Angus, aged nineteen, c. 1919

Was Marinoff referring to a child or simply using “Baby” to address Van Vechten as she often did? In an echo of the circumstantial evidence that exists for the possible adoption of Anna Snyder’s baby, a person close to Van Vechten’s family—Ralph’s wife’s sister—adopted an infant in hazy circumstances at some point between 1918 and 1920. Perhaps, Kellner ventures, the child was Van Vechten and Marinoff’s. The evidence is intriguing but not remotely concrete. It is true that around this time letters indicate that Marinoff was out of town for lengthy periods, perhaps a sign that she was attempting to conceal the pregnancy. However, her extended absences from New York for professional and personal reasons were a constant feature of the Van Vechtens’ half-century relationship and should not necessarily be seen as evidence of something untoward. It is more likely that Van Vechten embarked on such an intimate affair with Donald Angus because after seven years with Marinoff the heat of their early passion had cooled, and he felt the need for involved homosexual relationships to be so great that he could no longer ignore it. What is certain is that Marinoff knew about Van Vechten’s relationship with Angus from the start. If she harbored any jealousies or objections, she did not express them. In fact, she and Angus quickly became close friends, testament to the unusual but resilient arrangement that was the Van Vechtens’ marriage.

* * *

Several months into his affair with Angus, in January 1920, Van Vechten received his first letter from Mabel Dodge in five years. In it, she made no reference to the events in Italy in 1914 but asked for news of Fania and details of his latest work and told him about the mystical properties of a Native American ring she was forwarding, “for the good of your soul.” True to her word, she had long ago abandoned the Medici and Florence, as well as the grunt and grind of New York, to live among the indigenous peoples of New Mexico, and, free from the suffocating embrace of Western civilization, reconnect with nature. Writing just days after the Volstead Act brought Prohibition into effect, she may have thought this the perfect time to offer salvation to the pleasure seekers of Manhattan she had left behind. The ring she sent Van Vechten “has very strong (molecular!) vibrations,” she assured him, “and if you wear it you will see the effects from it in your everyday life,” though quite what they might be she did not relate, and Van Vechten decided it easier not to ask.

Within a month the two were corresponding as freely as if the recent years of silent hostility had never passed. Van Vechten was delighted to have her back in his life. Every time he received one of Mabel’s letters, he told her, his brain and muscles raced as they would had he snorted a line of cocaine. She confessed that he excited her every bit as much, though she was always wary of his caustic wit. “Your enhancing appreciation ought to be eagerly claimed and craved by all kinds of personalities of your time,” she said of his book Interpreters and Interpretations, a volume of essays on his favorite performers. “I would crave it for my own perpetuity did I not fear it more than I desire it! For there is a terror lurking in your pages though I don’t know exactly where in it lies. Maybe your wit is a little horrific at times—maybe your smile is full of little daggers.” Little did she know that at that very moment Van Vechten was securing her “perpetuity” as one of a cast of characters in his first novel.

As he approached his fortieth birthday, Van Vechten had decided to attempt writing a novel because he feared he was a spent force as a critic. He “held the firm belief that after forty the cells hardened and that prejudices were formed which precluded the possibility of welcoming novelty.” Less quixotically, he was irritated that his brilliance had earned him eminence and prestige but not fame and fortune. Writing novels, he said, “not only brings one money, it also brings one readers.” Primarily, Peter Whiffle: His Life and Works is a fictional biography of a would-be writer who spends his life preparing to write a great work of literary genius but never commits a single word to paper because of what he describes as an “orphic wall of my indecision.” Van Vechten narrates the story as himself, the conceit being that Whiffle’s dying wish was for his friend to write the tale of his life, which Van Vechten agrees to do as “a free fantasia in the manner of a Liszt Rhapsody.” Whiffle, who is essentially a composite of Van Vechten and Avery Hopwood, flits from one crowd to another in constant search of new sensations through art, illicit love affairs, alcohol, drugs, and the occult. His experiences mirror many of Van Vechten’s memories of his own early adulthood: he plays piano in a Chicago brothel, quaffs champagne in Paris, luxuriates in the riches of the Uffizi. Yet each event is like a fairy-tale reimagining of the truth in which senses are overstimulated, logic dissipates, and people from the real world are bent into curious new forms as in a Coney Island hall of mirrors. Even though he fails spectacularly as a writer, Whiffle eventually realizes that he has turned living into an art form of the highest kind, the type of project that Van Vechten himself was engaged in. “I have done too much, and that is why, perhaps, I have done nothing,” Whiffle says to Van Vechten the final time they meet. “I wanted to write a new Comédie Humaine. Instead, I have lived it.” The novel’s moral is delivered in a maxim that is unmistakably Van Vechten’s own: “It is necessary to do only what one must, what one is forced by nature to do.”

The novel was published in 1922, a literary year best remembered for two towering masterpieces of high modernism, Ulysses and The Waste Land, as well as early novels by a couple of future colossi of American letters, The Beautiful and Damned, by F. Scott Fitzgerald, and The Enormous Room, by E. E. Cummings, both of which crackled with the rebellious energy of the young postwar generation. That same year Sinclair Lewis gave capitalist America a swift poke in the ribs with Babbitt. It was a remarkable crop for one year, and at first glance the brittle decadence of Peter Whiffle seems glaringly out of place in that milieu. Yet the novel was not quite the florid misfit it now appears. Van Vechten was one of a number of successful but now mostly obscure novelists from the twenties loosely bound together by an appreciation of frivolity and fantasy, whom the literary critic Alfred Kazin aptly dubbed the Exquisites. All were united by an obsession with aesthetics, imagining themselves to be Oscar Wilde or J-K Huysmans with an American accent in an ambitious age of automobiles, airplanes, and moving pictures. The notional figurehead of this group was James Branch Cabell, whose novel Jurgen caused a scandal upon its publication in 1919. Though set in some indeterminate past, the novel deals with a thoroughly twentieth-century concept—sexuality—and is full of Freudian imagery, phallic symbolism, and very obvious double entendres. Van Vechten was a huge admirer of Jurgen, and its spirit of salacious adventure resounds throughout his own fiction.

Peter Whiffle also makes more sense when placed into Van Vechten’s bespoke canon of American fiction, which he publicized in magazine articles in the late teens and early twenties, one populated by unusual and long-forgotten writers, most of whom discarded realism for fantasy and scabrous pleasures of the flesh. At the center was the great lost American genius Herman Melville. Van Vechten’s tart, mannered sketches of life among New York aesthetes could scarcely be more dissimilar to Melville’s sprawling tales of travel and adventure. Yet in Melville’s voracious appetite for life, his taste for subversion, and the threads of sexual ambiguity that run through his work, Van Vechten detected a kindred spirit, one he thought should be recognized as a giant of the nation’s artistic heritage. Since the publication of his last novel, The Confidence-Man in 1857, Melville’s reputation had dwindled rapidly. By the time of the First World War his name was unknown to all but a tiny literary elite. The Melville revival began in earnest in 1921, when Carl Van Doren devoted an entire chapter in his book The American Novel to Melville’s work. In a smaller way Van Vechten joined the fray later that year with a piece about the character of the American novel in a Yiddish newspaper edited by Jacob Marinoff, Fania’s brother, in which he suggested that Melville was one of the foundation stones of the nation’s literature. A month later the first biography of Melville was published: Herman Melville: Mariner and Mystic, by Raymond Weaver, which Van Vechten reviewed positively in the pages of The Evening Post on New Year’s Eve 1921. The following January he issued the most strident claim made by any agent of the Melville revival, comparing Moby-Dick to Hamlet and The Divine Comedy in both the majesty of its construction and its importance to a national literary tradition. It is, he said, “Melville’s greatest book, assuredly one of the great books of the world,” the sort of opinion that is entirely commonplace in the early twenty-first century but seemed conspicuously eccentric at the time, if not willfully perverse.

In Moby-Dick, Mardi, and Pierre, Van Vechten identified Melville as someone more than a writer: he was an intrepid adventurer whose epic imagination was matched only by his unflinching bravery. Here was a true “cosmopolitan, a sly humorist,” Van Vechten said, “[a] man who ballyhooed for a drunkard’s heaven, flaunted his dallyings with South Sea cuties, proclaimed that there was no such thing as truth, coupled ‘Russian serfs and Republican slaves’ and intimated that a thief in jail was as honourable as General George Washington.” It was the sort of description that could have been written of Peter Whiffle and surely one that Van Vechten hoped might one day be written of his creator.

* * *

When Mabel Dodge received her copy of Peter Whiffle, she was delighted that Van Vechten had captured so perfectly the emancipated spirit of their society. “Why don’t you decide to be a kind of chronicler of your time & do dozens?” she suggested. “Times change—it would be an amusing record. Like Saint Simon & S. Pepys.” In her curiously shamanic way, she had unknowingly suggested a type of project that he had already begun. In February 1922 Van Vechten started a diary to capture the events and atmosphere of the times, beginning just weeks before Peter Whiffle was published and ending amid the Depression in 1930. Like the minute scrawls of his college diaries, this was not a confessional journal through which he mediated his demons, but rather what he called his daybooks: lists of the people, places, and objects that whirled in and out of his life, his instincts as a writer overruled by the compulsions of a collector. Perfunctory though many of the entries are, they amount to a striking document of 1920s’ Manhattan, full of the fights, flings, petty jealousies, and indiscretions of the canonical names of the decade—and, of course, a fast-flowing stream of revelations about his own life.

“The Twenties were famous for parties,” he wrote in a recollection of the decade in the 1950s; “everybody gave and went to them; there was always plenty to eat and drink, lots of talk and certainly a good deal of lewd behavior.” For once Van Vechten was guilty of understatement. In the unexpurgated, private pages of his daybooks the fevered excess of what he called “the splendid drunken twenties” fills every page, the entries themselves often scribbled through the fog of a hangover. His social calendar was crowded and wildly diverse. During a typical three-week period in late April and early May 1922, his engagements included a recital by the composer George Antheil, a tea party at the Stettheimer sisters’ with Marcel Duchamp, an after-show party with Eugene O’Neill at the Provincetown Playhouse, a performance of the vaudeville revue Make It Snappy, starring Eddie Cantor, and Geraldine Farrar’s farewell appearance at the Metropolitan Opera House, all dotted around the ubiquitous cocktail parties.

The reek of bootleg gin hung permanently in the air like background radiation. The Van Vechten family table in Iowa had always been dry, but neither Carl nor Ralph followed their father’s abstemiousness, and both were enthusiastic drinkers their whole adult lives. Prohibition did nothing to curb either’s habits, and in Carl’s case it only increased its attraction, turning what had previously been a largely benign indulgence into another marker of bohemian sophistication, another medium of rebellion. He had two regular bootleggers: Jack Harper, who with his wife, Lucile, also ran a trendy speakeasy, and Beach Cooke, one of New York’s most successful hooch merchants. He and Marinoff were never without a sizable stash of champagne, gin, and whiskey, and out-of-town friends knew that the Van Vechtens could always fix them up with good-quality liquor. Easy access to alcohol was as important to Van Vechten’s public image as a Manhattan trendsetter as was his acquaintance with Gertrude Stein. When Ralph came to visit New York in the summer of 1922, Carl took him for a night out at Leone’s, a highly fashionable speakeasy, where Ralph proceeded to embarrass his little brother by bungling Prohibition etiquette. Impressed by his surroundings, Ralph had inquired about getting a membership card, but to protect his reputation as a respected banker, he assumed an obviously false identity to do so. Ralph “makes a provincial ass of himself” was Van Vechten’s exasperated judgment in his daybook.

“Provincial” rather than “ass” was the insult here, about the worst thing Van Vechten could imagine being said about anyone. Florine Stettheimer completed a portrait of him around this time that perfectly captures his self-image as the embodiment of contemporary chic and so pleased him that he sent photographs of it to friends far and wide, including Gertrude Stein in France. In it he sits with his legs crossed in a black suit in the middle of his red and gold apartment, as sleek and slim as the cigarette balanced between his clawlike fingers, though in reality the onset of middle-aged spread was expanding his frame quite rapidly. Surrounding him are his cherished possessions: his erudite books and prowling cats, his objets d’art and piano. And in the corner is a fairground sign lit up by electric lights suspended above a miniature merry-go-round, a reference to the title of one of his volumes of essays, but also a metaphor for the life that he led, a brightly colored whirl of amusement.

The only thing missing from Stettheimer’s canvas was Van Vechten’s coterie of friends, of both sexes, young enough to be his children. They all were either beautiful or talented, or both. The hyperactive silent movie star Tallulah Bankhead became a particular favorite. She could often be found making an exhibition of herself at the Algonquin Hotel, where Van Vechten spent oceans of time either in the dining room or upstairs, taking illicit cocktails in the private quarters of Frank and Bertha Case, the couple who ran and later owned the hotel. Bankhead’s loud extroversion annoyed many of the Algonquin’s more serious-minded patrons, but Van Vechten found her antics hilarious. At one of his parties she provided a star turn when she “stood on her head, disrobed, gave imitations & was amusing generally.” For more sedate reasons, he also found the company of the not-yet-famous George Gershwin, an “egotist” of “considerable charm,” to be a welcome addition to any social occasion as he filled the room with the strains of his early compositions “Swanee,” and “I’ll Build a Stairway to Paradise.” Van Vechten himself had been playing the piano at a party in April 1922 when he met another dazzling young talent, F. Scott Fitzgerald, for the first time, the same night that the publisher Horace Liveright, in a drunken moment of horseplay threw Van Vechten off the piano stool and broke his shoulder.

Tallulah Bankhead, c. 1934, photograph by Carl Van Vechten

The youthful friends and lovers, the parties and the constant drinking: they all were ways of trying to repudiate the passing of his own youth. Van Vechten regarded himself as a late starter who had wasted the first sixteen years of adulthood and had only begun to fulfill his potential after the life-changing events of 1914. He was determined to make up for lost time and did so by turning the city into his playground. This frivolous, self-indulgent atmosphere formed the backdrop for his next book, The Blind Bow-Boy, a whip-smart, funny, and deceptively insightful novel about a group of New York sybarites. It is Van Vechten’s best piece of fiction and one of the great forgotten American novels of the 1920s. The story, which has a far more conventional structure than Peter Whiffle, is essentially an off-kilter retelling of A Rake’s Progress in which Harold Prewett, a timid, straightlaced college graduate, is sent to Manhattan by his wealthy father to be educated in the ways of the world by Paul Moody, a socialite and louche gentleman of leisure. On the surface, Moody is a younger Van Vechten; he got the job as Harold’s “guide to fast life” because he is “of good character but no moral sense” and had once been sentenced to the Ludlow Street Jail for refusing to pay his ex-wife alimony. However, it is Moody’s beguiling female friend Campaspe Lorillard who expresses Van Vechten’s interior world, his core personality and opinions on life. It is she who lives on the Block Beautiful, who rhapsodizes about Manhattan and reads widely and voraciously, casting her eye over her circles of friends while musing on the curiousness of “the manly American” and the hidden desires that lurk within us all.

Between them, Moody and Lorillard introduce poor innocent Prewett to avant-garde composers, fairground snake charmers, speakeasies, casual sex, fine dining, and all the other sensual pleasures of 1920s Manhattan. It is a story of Harold Prewett’s loss of innocence and self-discovery that cleverly doubles as a coming-of-age tale for the United States. When Prewett, a representative of Van Vechten’s puritanical and conservative America, is taken on his first trip to Coney Island, he is assaulted by the spectacle of modern consumerism: “Ferris wheels, airplane swings, merry-go-rounds, tinsel and marabou, hula dolls, trap-drummers, giant coasters, gyroplanes, dodge ’ems.” Prewett is overwhelmed; Lorillard, ecstatic. “It’s superb,” she gushes. “It’s all of life and most of death: sordid splendour with a touch of immortality and middle-class ecstasy … It is both home and the house of prostitution. It is … complete experience. It is your education.”

The one marvel of modern New York that Van Vechten could not write about overtly was homosexuality, though the subject is woven right through the story, using the language of codes and symbols that were a vital part of gay life in the real world. The effeminate clothing, vocabulary, and mannerisms of certain characters mark them out as homosexual without any categorical identification. The most obvious example is an English aristocrat by the name of the Duke of Middlebottom, a double entendre that seems to have eluded most readers at the time, whose motto is “A thing of beauty is a boy forever.” Some of the codes were censored when the novel was published in Britain, but in the United States the book was left untouched. Either the references went unnoticed, or in the “anything goes” atmosphere of the Jazz Age, a little leeway was considered acceptable.

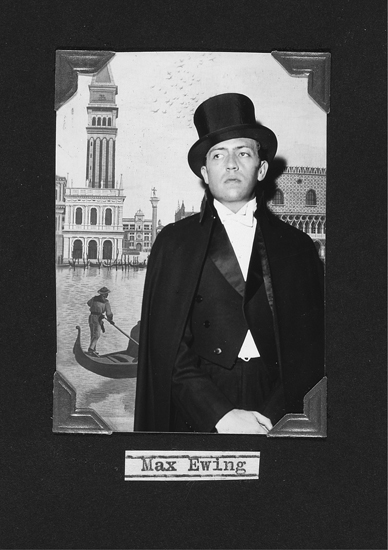

The Blind Bow-Boy is a masterpiece of camp, written decades before the term and concept came into existence, and it sealed Van Vechten’s hero status to a small but discerning group of gay, literary-minded cosmopolitan men. Van Vechten was one of the first cultural figures to draw New York’s gay subculture into mainstream visibility, leading ultimately to the so-called pansy craze of the early 1930s and the huge success of overtly homosexual cabaret performers such as Gene Malin. As the historian George Chauncey explains, the revolt against Prohibition that created the speakeasy culture fostered other types of cultural rebellion, including the increasing prominence of homosexuals in public life. A year after The Blind Bow-Boy was published the magazine Broadway Brevities complained about the “impudent sissies that clutter Times Square.” There had been other American writers to include veiled themes of homosexuality in their novels, but few had done it with such verve or indelicacy as Van Vechten. His novels spoke to a gay audience with an urgency that many heterosexual readers, even those who admired his work, did not experience. One reader wrote Van Vechten to thank him for portraying his sexually unconventional characters not as freaks but rather as people in search of happiness because “that is what any so-called pervert wants although he risks jail everytime he reaches for that happiness.” Another young fan who picked up on the subtexts and codes was Max Ewing, a midwestern boy studying at the University of Michigan. Ewing, homosexual and a talented writer, began corresponding with Van Vechten in 1922 for a profile in a student newspaper. Their correspondence made no explicit reference to anything sexual, but there can be no doubt that by the time that Ewing visited Van Vechten in New York for the first time in October 1923 both knew of their shared orientation. The evening Ewing arrived in town, Van Vechten took him to a party in honor of The Blind Bow-Boy, thrown by Lewis Baer, a member of what Van Vechten had begun to call the jeunes gens assortis, the group of young, handsome gay men whom he collected around him and who, like Donald Angus, received the benefits of his educating influence. The term had originally been coined by Jacques-Émile Blanche to describe Mabel Dodge’s coterie of young men, but when Van Vechten appropriated it—admittedly with tongue in cheek—it acquired an extra layer of significance.

Max Ewing, c. 1932

Seen from a distance of eighty or ninety years, the 1920s often seem a time of striking sexual liberation but usually of a distinctly heterosexual nature. Images of flappers in thick lipstick and high hemlines being pursued by girl-crazy men, as in Anita Loos’s Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, and the love stories of glamour couples, such as Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbank, have created a popular notion of a time in which men were men and women were women. Many of the emblematic writers of the era who have been laid to rest in the mausoleum of Great American Novelists are also of a priapic and unambiguously heterosexual sort. Van Vechten wrote novels that offer a glimpse of the pansexual currents of the moment. In a pre-Stonewall world homosexuality was not openly expressed and embraced, but it was there all the same; you just had to know how to decipher its symbols. And with Van Vechten, those symbols were far from Delphic. Long after Van Vechten’s death—and some years after the Stonewall revolution—one of his young male admirers said it best: “He knew everyone knew, but he wasn’t going to carry a placard down Christopher Street on Gay Day.”

* * *

The Blind Bow-Boy hurled its author to new heights of popularity. That summer of 1923 Carl Van Vechten was celebrated as a literary sensation. Sinclair Lewis wrote a letter of congratulation that delighted him because it got closest to identifying what he had attempted to express. “It is impertinent, subversive, resolutely and completely wicked,” Lewis raved. “You prove that New York is as sophisticated as any foreign capital.” The influential Chicago critic Fanny Butcher lauded him as one of the most essential novelists of the moment, and The Blind Bow-Boy was probably the sole Van Vechten novel that Scott Fitzgerald genuinely admired. A new friend, the Vanity Fair artist Ralph Barton, thought Van Vechten worthy of one of his caricatures, considered an unofficial sign that one was a star in the 1920s. Universal Pictures even entertained the idea of adapting The Blind Bow-Boy into a movie. After a lengthy period of consideration Van Vechten’s contact at the studio, Winnifred Reeve, eventually got in touch to say that it was going to pass up the opportunity to buy the rights to the picture but forwarded the reader’s report as way of explanation and for his amusement. The reader summarized the novel as a tremendously fun tale revolving around a “sissy hero” who is given “a liberal education in matters of sex.” The book would be of great interest to the “neurotic cognoscenti,” the report concluded, “but not for the radio or motion pictures.” Van Vechten noted each letter of congratulation and each word of praise in his daybooks. All the attention came as a relief, confirmation that he really was the special talent that he had believed himself to be for so many years.

Van Vechten’s new glitterati status was of no interest to the members of his family, who were shocked and embarrassed by the contents of his latest book. When Peter Whiffle was published, Charles Van Vechten had ordered copies for friends and relations and beamed with pride when people around town asked him questions about his boy, the novelist. While the book may have been a little racy at times, it all was handled in a civilized, intelligent manner. The Blind Bow-Boy, however, was smut from start to finish. “The new book is a very well written picture of depravity,” wrote an exasperated Charles after reading the offending volume. “Not a decent character in the book. It will shock and disgust many readers. While apparently written to amuse it isn’t amusing at all.” He still intended to order copies for various friends who were fans of Peter Whiffle, but “what they may think of it, I don’t know.” Just before Christmas Charles wrote again to say that though the book was a Cedar Rapids bestseller, nobody ever dared discuss it with him. Uncle Charlie offered praise of what he thought was a “very clever” novel, which was “here and there brilliant,” but teased Van Vechten that other members of the family took a dimmer view: “Aunt Mary says that it is a dirty book and that you ought to be ashamed of yourself.”

Van Vechten was anything but that. Success as a novelist brought notoriety, influence, and wealth. “Very suddenly, out of the clear sky,” he remembered of 1923, “I began to make a great deal of money.” When his brother, Ralph, came to New York on business in December, Van Vechten took him, Avery Hopwood, and their friend Ernest Boyd for a slap-up meal at the Algonquin. The occasion was recorded in his daybook with the information that he, rather than Ralph, paid. At the age of forty-three Van Vechten could finally afford to pick up the check. It was a far more important milestone than he would like to have admitted. In the Van Vechten family making money was the mark of a successful man, and the need to make his writing pay had been a constant refrain from his father for the last twenty years. Ralph had been no less attentive on the matter in recent times. After one rebuke from his brother in February 1919 about the parlous state of his finances, Carl had replied with a lofty defense of his art. “The kind of writing I do requires time for reflection,” he said, as well as all manner of expenses. “It is one thing or the other for me, either to settle down for a career of a mediocre journalist or to strive for something better.” He had finally managed to achieve what had thus far been illusive: fulfillment of his creative ambitions combined with the financial success that his family valued.

Making a point to the folks in Cedar Rapids was at the heart of Van Vechten’s intentions for his next novel, The Tattooed Countess. Concerning the teenage rebellion of an ambitious and artistic boy named Gareth Johns against the dull rectitude of a midwestern town in the summer of 1897, the story is an obvious retelling of Van Vechten’s own adolescence. Van Vechten’s escape route from Cedar Rapids had been college life in Chicago. Johns finds his way out of Maple Valley in the embrace of Countess Ella Nattatorini, a woman who left town many years ago to seek a life of refined indulgence in Europe, marrying an Italian aristocrat along the way before his death left her a wealthy widow, free to travel, live, and love as she saw fit. Recently turned fifty and jilted by a caddish French lover, she returns to her hometown to visit her kindhearted but prudish sister and scandalizes the local gossips by smoking cigarettes, wearing makeup, and having a French phrase tattooed on her wrist, “Que sais-je?,” an apparent reference to the ironic skepticism of Michel de Montaigne. Bored rigid by the people of Maple Valley and their narrow universe, she eventually embarks on a passionate affair with the seventeen-year-old Johns, the one person in town in whom she detects a spark of life.

Nobody emerges from The Tattooed Countess particularly well. With few exceptions, Maple Valley’s residents are portrayed as benign but comically small-minded, while the countess, for all her sophistication, “alert intelligence,” and “abounding vitality,” is presented as the proverbial mutton dressed as lamb, “at that dangerous and fascinating age just before decay sets in.” Rarely was Van Vechten crueler in print than in ridiculing this creation of his, a middle-aged woman who still had the temerity to think herself attractive to younger men. For that sin, Van Vechten thought, she deserved to be pitied and scorned. To his friend Hugh Walpole, to whom the novel was dedicated, he derided the countess as “a worldly, sex-beset moron,” who was taken for a ride, in every sense of the term, by a “ruthless youth” of “imaginative sophistication.” To the poet Arthur Davison Ficke, with whom Van Vechten enjoyed swapping sexual gossip, he suggested The Tattooed Countess had a double meaning as “the Countess was certainly full of pricks.” The ironic similarities between her predicament and his own—a middle-aged man of expanding waistline and receding hairline, still yearning for the attentions of brilliant boys—does not appear to have struck him. Of all the characters, Gareth Johns, the “ruthless youth” in possession of “imaginative sophistication,” fairs best. Although his yearning for a life of excitement makes him cynical and calculating beyond his years, he takes control of his situation and ultimately gets what he wants when the countess whisks him off to Europe. There was never any ambiguity about who was the model for Johns, and Van Vechten’s sister, Emma, believed he had got his teenage self down to a T. There are even veiled hints that Johns, like the adolescent Van Vechten, struggles with his sexuality. Despite being slavishly adored by the Countess, his beguiling English teacher, and a pretty female schoolmate, Johns never feels a spark of passion for any of them. He simply exploits their affections and discards them when their purposes have been served.

Cynicism and irony abound in The Tattooed Countess, slyly subtitled “A Romantic Novel with a Happy Ending.” The joke there was that the “happy ending” was in fact the novel itself. As the real-life Gareth Johns, Van Vechten had come back to haunt and taunt the Midwest of the nineteenth century and in so doing created his bestselling work to date; the book sold in excess of twenty thousand copies in its first month on the shelves. Baiting provincial America was not in itself tremendously noteworthy; it was a favored sport of many writers and intellectuals in the 1920s. Since the end of the war, both Sinclair Lewis and Sherwood Anderson had written acclaimed fiction that lampooned the manners and mentalities of the Midwest, and various state-of-the-nation works such as Civilization in the United States expressed the fashionable opinion that the United States of eastern intellectuals was weighed down by the country’s old-fashioned, reactionary heartland. Van Vechten was faithfully following the trend, posing, as other writers had done before him, as the chic prodigal son returning home, holding in one hand a color-tipped cigarette and wielding a hatchet in the other, guffawing at the yokels as he hacked away.

The novel was published in August 1924. In October he visited Cedar Rapids and smirked at how accurate his derision of the place had been. William Shirer, later the acclaimed chronicler of the early years of Nazi Germany, was then a twenty-year-old college student who lived with his parents a few doors from the Van Vechtens. He recalled meeting Carl, whom he described as “a sort of invisible force, especially for the young and rebellious in our town” and talking to him about literature and life in New York. Van Vechten’s advice to him, “off the record,” was to “get the hell out of Cedar Rapids as quickly as possible.” Yet disdainful as he was of its charms, Van Vechten could never quite abandon his hometown. During his visit that fall, he wrote Marinoff that the whole place was talking about his book and described his glee at being reviled and feted all at once. He happily gave interviews for two local newspapers, smiling wryly as he protested that the novel was a work of pure imagination. Being liked by the townsfolk or gaining their approval was not important to him, but having their attention was. Tellingly, in the voluminous scrapbooks of press clippings through which he charted the progress of his public reputation over the decades, the judgments of reviewers from Cedar Rapids are always reserved a spot alongside Franklin Pierce Adams, Alexander Woollcott, and the other metropolitan writers. The Iowan critics were usually rather kind, even with The Tattooed Countess, proud that the son of a local family was among Manhattan’s brightest stars. Van Vechten never decided which he should cherish more, their praise or their opprobrium, but he kept tabs on both all the same.

* * *

The spread of Van Vechten’s fame from New York to the Midwest and beyond did not dull his efforts as a promoter of causes. Far from it; the boost to his celebrity only gave him more opportunity to put his stamp on the nation’s culture and extend his reputation as a tastemaker. It was almost a compulsion; there was nothing that made him feel more vital.

As Peter Whiffle, The Blind Bow-Boy, and The Tattooed Countess flew off the shelves, Van Vechten used his contacts and influence to further the careers of numerous American writers. He convinced Knopf to publish Harmonium by Wallace Stevens and came close to pulling off the same feat for Gertrude Stein’s The Making of Americans. Elinor Wylie felt so indebted to his public support of her novel Jennifer Lorn she gave him a copy inscribed, “Carl Van Vechten … But for whom this book would never have been read.” In cheering on American talent Van Vechten was following the postwar trend of boosting previously underappreciated American culture, from Herman Melville to Native American folk art. Indeed, it was a trend that he had been instrumental in starting with his advocacy of art as diverse as Leo Ornstein, African-American theater, and Gertrude Stein.

However, his advocacy was by no means restricted to Americans. In the early twenties one of Van Vechten’s great successes was an eccentric Englishman by the name of Ronald Firbank, whose hammy comic novels made Van Vechten’s look like sober tracts of social realism. His introduction to Firbank’s writing came in February 1922, when James Branch Cabell’s editor, Stuart Rose, recommended Firbank’s novel Valmouth, a frothy comedy of manners set in an English spa town, with a barely concealed subtext about interracial and homosexual sex carried out between characters with names such as Dick Thoroughfare and Jack Whorwood. Van Vechten saw Firbank as a fellow rebel against propriety and a man who, like him, found it impossible to dilute his true inner self. Sensing the opportunity to claim him as his latest cause, he immediately wrote Firbank to announce himself as his unofficial American publicist, revealing that he had already produced an article about him for the April issue of The Double Dealer—Firbank’s first notice in the United States—and more would follow. Firbank was bashful in his reply but also clearly excited by Van Vechten’s enthusiasm, and the two began a long-distance friendship through correspondence. Though they had never met—and indeed never did meet; Firbank died suddenly in 1926—they established a close bond, their shared homosexuality at its core, always bubbling beneath the surface of their warm and humorous letters but never overtly mentioned.

Over the summer of 1923 the two swapped gifts via airmail. Van Vechten sent Firbank a copy of the record that the United States was crazy about, “Yes, We Have No Bananas,” a song so wonderfully mindless and vulgar, Van Vechten said, it was the anthem of the national mood. In return, Firbank sent a photograph of himself that Van Vechten hung in his bathroom, in a space between a couple of his favorite divas, Mary Garden and Gaby Deslys. More important, he sent his latest novel, Sorrow in Sunlight. Set in the West Indies, the story is a fish-out-of-water tale about a black family from the country who go to the city to find their fortune and shin their way up the social ladder. Bouncing along with all the social comedy, frivolity, and innuendo that he so admired in Firbank’s writing, Sorrow in Sunlight delighted Van Vechten, who took it into his own hands to find the book an American publisher. On September 19 he wrote to Firbank to say that Brentano’s was keen on publishing it, as well as all his previous novels, for the American market. With extreme presumptuousness, Van Vechten also mentioned that he would of course write the preface for Sorrow in Sunlight should this happen. On October 30, he contacted Firbank again to explain that he had been thinking the matter over and had decided that Sorrow in Sunlight was a dreary title. A particular phrase from the novel would be much better: Prancing Nigger. With this title, he assured Firbank, audiences would know immediately that the book was exotic, naughty, and fun, and sales would increase enormously. Brentano’s agreed: he had already told the editors, and they were set on it. The final decision was Firbank’s, but Van Vechten let him know that rejecting the new title would be foolhardy. “Beyond a doubt,” he said, “the new title would sell at least a thousand copies more.”

Firbank agreed to rename the book—the “title is delicious,” he told Van Vechten in November—and arrangements were made for publication in the spring of 1924. He was sincerely thankful for, and flattered by, Van Vechten’s interest in him but startled that Van Vechten had been discussing publication deals for his books without telling him first. Van Vechten had championed causes with great enthusiasm before, but this was something else. The Blind Bow-Boy had been published just months earlier, and his ego was surging. Never before had he been so sure of the correctness of his opinions. The notion that Firbank might have objected to his interference never entered his thinking. Over the coming years this proprietorial attitude became a recurring feature of his promoting, dispensing orders and grave words of advice in a voice strangely reminiscent of the one both his father and his brother used when lecturing him on financial matters. A close friend once remarked that Van Vechten had “an autocratic way of taking possession of things he wanted.” That was especially the case when the thing he wanted could bolster his reputation. When Prancing Nigger, complete with Van Vechten’s preface, was published later in 1924, the American public knew that Firbank was Van Vechten’s discovery. Firbank apologized if some of the outraged reviews the book received from conservative critics harmed Van Vechten by association. “My books are quite unconventional,” he wrote, “and shock a lot of people (even in England) and you were brave to champion them.” Van Vechten assured him that apologies were unnecessary; riling the critics and attracting controversy were all part of the fun.

The following year Van Vechten’s certainty in his tastes spilled over into hubris when he wrote the introduction to Red, a collection of essays that was his swansong to music criticism. “I seemed always to be about ten years ahead of most of the other critics,” he wrote, immodestly but accurately, in 1925, looking back over his career as a critic. In 1915 he had published his prediction that the primal rage of Stravinsky would conquer America; in 1924 Le Sacre du Printemps finally made its New York debut. And now, he assured his readers, he was about to be proved right about African-American music too.

He may have sounded insufferably arrogant, but there is no question that he was correct. Two years earlier, in November 1923, jazz reached an important crossover moment when, accompanied by George Gershwin, the mezzo-soprano Eva Gauthier dedicated the second half of her “Recital of Ancient and Modern Music for Voice” at Aeolian Hall to ragtime and jazz tunes, an unprecedented move that Van Vechten claimed was originally his idea. There is no definitive proof of that, but it does sound strongly plausible. Nowadays Gershwin and Gauthier do not seem like such a strange pairing. In 1923 it was the sort of perverse scheme that only someone like Van Vechten would have dreamed up, like his suggestion to The Morning Telegraph in 1918 that Irving Berlin should collaborate with Gertrude Stein. In the weeks following Gauthier’s recital, American newspapers and magazines earnestly debated the question of whether ragtime and its offshoots should be taken seriously as great American art—approximately eight years after Van Vechten had caused irritation and disbelief for suggesting they most definitely should and more than a decade after he had written an apologia for ragtime in The New York Times.

One evening the following January Van Vechten stopped in at the sumptuous West Fifty-fourth Street home of the arts patron Lucie Rosen, where he and a select group of other guests enjoyed a repeat performance of Gauthier’s and Gershwin’s unique double act. After they were through, Gershwin hung around at the piano and gave a sneak preview of a brand-new piece he had written for another upcoming concert at Aeolian Hall, “An Experiment in Modern Music,” curated by the orchestral director Paul Whiteman. It was Gershwin’s first long-form concert piece, and he had a title for it that encapsulated its fusion of African-American and classical traditions, Rhapsody in Blue. Though it was only a fragment, Van Vechten was rapt by what he heard. A week before the concert he spent an afternoon in the stalls at Aeolian Hall, listening to Gershwin play the whole of Rhapsody in Blue twice. The concert on February 12, which Van Vechten attended with his friend Rebecca West, proved crucial in establishing Gershwin’s credentials as a composer and the reputation of jazz as a “serious” musical form. It was also the moment that convinced Van Vechten that his predictions about the art form were coming true.

So ardent was Van Vechten’s belief in the potential of jazz he seriously considered an intriguing proposition from Gershwin a few months after the Whiteman concert, a collaboration on a jazz opera about black America, for which Van Vechten would write the libretto and Gershwin the score. “He [Gershwin] has an excellent idea,” Van Vechten told Hugh Walpole in October ’24, “a serious jazz opera, without spoken dialogue, all for Nègres!” Despite his excitement, the project never got off the ground, though Gershwin persevered with the idea and of course eventually wrote Porgy and Bess with his brother, Ira, and DuBose Heyward. Of the respected, established music critics of the day, Van Vechten was unusual in his zeal for jazz. Even Paul Rosenfeld, the man who took on Van Vechten’s mantle as America’s leading advocate of modern music, obstinately rejected the notion that jazz could be considered great art and cited its influence on Aaron Copland as that composer’s greatest flaw. By the time he came to make his valedictory comments in Red, published in 1925, Van Vechten’s mind was certain on the matter. “Jazz may not be the last hope of American music,” he conceded, “nor yet the best hope, but at present, I am convinced, it is its only hope.”

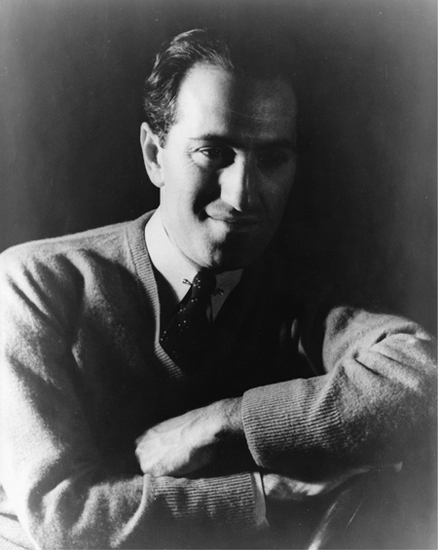

George Gershwin, c. March 1937, photograph by Carl Van Vechten