Apple, Google, Microsoft, and Samsung

APPLE

“We’re going to make some history together today.” With those now famous words, Apple CEO Steve Jobs took the stage to debut the iPhone at the annual Macworld conference in San Francisco on January 9, 2007. After running through some other announcements, Jobs pulled an iPhone out of his jeans pocket. The phone’s design was striking. It had a glossy, 3.5-inch high-resolution screen dotted with colorful icons and surrounded by a shiny, stainless-steel rim. At 4.5 inches by 2.4 inches by 0.46 inches, the iPhone was also thinner than most other phones on the market.

Original iPhone (far left) and newer iPhones (Yutaka Tsutano/Flickr)

Jobs spent the next 90 minutes electrifying his audience as he outlined the iPhone’s features. There was the “revolutionary [user interface], the result of years of development”; a “supersmart,” multitouch screen that could discern gestures and “works like magic”; an operating system “five years ahead of what’s on any other phone”; iPod software that let users “touch your music”; a virtual keyboard that’s “really fast to type on”; and the “first fully usable browser on a cellphone.”1 Apple, said Jobs, wanted to “leapfrog” current smartphones and create “a product that’s way smarter and easier to use.” To punctuate his point Jobs displayed a photo of some leading smartphones. The picture included a Palm Treo, a BlackBerry Pearl, a Symbian-powered Nokia E62, and a Windows Mobile–powered Motorola Q. “After today, I don’t think anyone’s going to look at these phones in the same way again,” Jobs said, and although his presentation was laden with hyperbole and showmanship, he was right. Next to the iPhone, these high-end phones, which had comparatively small screens and built-in QWERTY keyboards, suddenly seemed passé.

Jobs hadn’t always been so enthusiastic about smartphones or supermobile computing. He didn’t like the way the carriers controlled the smartphone business, and he was acutely aware that the smartphonelike Newton had been a failure. Jeff Hawkins recalls approaching Apple in 2003 with Ed Colligan and Donna Dubinsky to discuss a possible collaboration with Handspring. Jobs wasn’t interested. As Hawkins tells it: “Steve goes up to the whiteboard and starts drawing. He says, ‘At the center of the world is your Mac, and then there’s music and video and this stuff. And there’s a teeny little circle over here, which is a handheld. Maybe some people have that. It’s not really very important.’” Hawkins had a different opinion. He leaped up to the board, drew a handheld computer, and told Jobs, “No, Steve, I disagree. This is going to be the center of your world.” Hawkins, Colligan, and Dubinsky think the meeting influenced Jobs to get into the smartphone business.

In his biography of Jobs, Walter Isaacson writes that the catalyst was cellphones’ encroachment on iPods, which was obvious by the mid-2000s. According to Isaacson, Jobs told the Apple board of directors, “Everyone carries a phone, so that could render the iPod unnecessary.”2 In 2005, Sony Ericsson introduced a line of Walkman music phones, and Nokia announced its intention to sell music phones branded XpressMusic, showing Jobs he was right to be wary of phone makers. Phones in both series had built-in MP3 music players.

Besides the music-phone threat, Jobs came to see cellphones as a large and lucrative new market. Apple was selling tens of millions of iPods a year, but cellphone makers were selling hundreds of millions of phones.3 Jobs started talking to Motorola about putting an iPod inside one of its cellphones. In 2005, the two companies unveiled the music-focused ROKR E1—the first cellphone that let people download music from iTunes, transfer it (via a computer and USB cable) and listen to it on an integrated iTunes music player. Dubbed the “iTunes phone,” it generated a huge amount of attention but was poorly received, due to its clumsy (non-Apple) software, sluggish response time, limited storage, and boring design. Jobs knew Apple could do a better job. As Phil Schiller, Apple’s marketing chief, explained in 2012: “At that time, cellphones weren’t any good as entertainment devices. That made us realize—maybe we should make our own phone.”4

Apple’s efforts to develop what would become the iPhone were shrouded in secrecy. Abigail Sarah Brody, a former Apple designer who contributed to the phone’s software, says the work was mysterious, exciting, and demanding. Brody had been at Apple since 2001, mostly designing the professional photo, video, and music editing applications Apple sells to Mac computer users. One day, in 2005, Brody was invited to become part of a team of three that included an engineer and an executive—one of a number of small groups Apple set up to assist with the iPhone’s design. She accepted. The trio’s assignment was to create a user interface for an upcoming device. All they were told was that the device used a “multitouch” screen.

Before the iPhone, few people were familiar with multitouch. Regular touchscreens, such as the type used in early smartphones and ATMs, can’t recognize gestures, because they can’t accurately decipher contact points from more than one finger or hand at a time. Research on multitouch technology began in the 1980s, but the specific kind used in the iPhone was mostly created in the late 1990s and early 2000s. That’s when a Delaware start-up called FingerWorks began leveraging research from the University of Delaware’s computer and electrical engineering department. According to a 2004 press release, FingerWorks’s technology consisted of “hardware and software elements for sensing, tracking, and interpreting the motion of multiple hands and multiple fingers on a touch imaging surface.”5 Apple, which had also developed some multitouch technology in-house, acquired FingerWorks and its technology in 2005.

After Apple “pulled” Brody into “the secret iPhone project,” as she describes it, she was given a multitouch screen so she could see what it entailed. It was “a crude prototype,” but she guessed she was working on a future phone. “After seeing the iPod, it was very logical that the next thing for Apple to make was an iPhone,” she explains.

To determine what size the phone’s icons should be, Brody measured how far her thumb could reach across the screen when she held the prototype. She asked the engineer in her team to do the same, since he had larger hands. “It was very simple; just using our bodies as a means to measure,” she recalls. “We wanted to have proper ergonomics and consistency in the user interface.” For the next six months Brody’s team focused on creating supremely user-friendly software.

Apple won kudos for the effort it put into the iPhone’s design, and it was an instant hit. People had speculated for years about a possible iPhone, but most thought it would be a cellphone infused with iPod features, like the ROKR E1. Apple easily exceeded expectations. Some reporters expressed skepticism about Apple’s foray into a highly competitive industry and the iPhone’s comparatively high price ($499 to $599, depending on the amount of storage capacity). But most raved about the device and Jobs’s thrilling presentation. As the New York Post put it: “Apple Cells It—Breakthrough iPhone Wows High-Tech Fans and Wall St.”6

Post-Macworld, Apple shares hit a then record high, while those of competing phone makers, including Motorola, Nokia, Palm, and RIM, slumped. Online searches for “iPhone” spiked as consumers clamored to learn more about the device. A Deutsche Bank analyst described initial customer interest as nothing less than “rabid.”7

The iPhone went on sale on June 29, 2007. Over the next year Apple sold 6.1 million. A $200 price drop (from $599 to $399) that Apple instituted in early September spurred purchases in the last quarter of 2007, though the move initially angered the early adopters who had bought the phone at full price. (Apple appeased those customers by giving them $100 in Apple store credit.) In 2008, Apple sold 14 million iPhones, handily beating its sales goal of 10 million for that year.

Not everything about the iPhone was as revolutionary as Jobs claimed. The camera was just two megapixels, had no flash, and couldn’t record video. The phone had no GPS, didn’t synch with Microsoft Outlook’s corporate e-mail client, and couldn’t edit Microsoft Office documents. Most controversially, the iPhone was only available on AT&T and ran on its EDGE network instead of 3G. The disparity between EDGE, dubbed 2.75G, and 3G was mostly one of speed. EDGE was about three times faster than GPRS but two times slower than 3G technology, which was live in 160 cities across the United States by the time the iPhone went on sale. The allure of 3G was mobile multimedia—the ability to quickly load Web pages, download music, and even stream online videos to their phones. A 2007 New York Times article noted, “Early reviews of the iPhone, while positive, have faulted the slower [EDGE] network because it will limit the palm-size wireless computer’s greatest strength—making the Internet easily accessible on the go.”8

Other phones at the time did support 3G, but where the iPhone leapfrogged over other smartphones was its user experience. It was a phone designed to serve users first, rather than carriers. People loved navigating their iPhones by tapping, swiping, and pinching their fingers. The Guardian called multitouch “the soul of the iPhone,”9 because it affected everything the user did on the device. Compared to other smartphones, the iPhone’s software felt speedy. “In typical smartphones at that time, the user interface was sluggish,” says former Nokia manager Jari Kiuru. “After pressing a button you’d have to wait for things to happen. The iPhone had a fast reaction.” The iPhone even seemed intuitive. Embedded sensors could detect ambient light conditions and the phone’s physical orientation and proximity to a user’s face. The sensors dimmed the phone’s screen accordingly and shifted its icons when the user rotated the phone. The device almost felt alive to former Ericsson CTO Nils Rydbeck. “Apple made the iPhone human, like an extension of your senses,” he says. “Steve Jobs moved smartphones from a technical mess to a thing you love.”

The iPhone also figured out how to translate the desktop Web experience to a much smaller screen. In his Macworld presentation Jobs characterized the iPhone as a “breakthrough Internet communicator” that “put the Internet in your pocket for the first time ever.” This was another instance in which he wasn’t exaggerating. On the iPhone the mobile Web seemed less cumbersome and limited, even without 3G. Instead of a simplified WAP mobile browser, the iPhone ran a mobile-optimized version of Safari, the Web browser Apple developed for its Mac computers. Through Safari, iPhone users could access the entire Web as it was originally designed, not just sites adapted for smartphone viewing. There was no laborious scrolling. Instead, users touched the screen to zoom in and out of sections they wanted to read. Safari also let users open multiple websites and switch between them, like on a desktop computer. Historian Marc Weber calls the iPhone “the first usable device for the mobile Web. . . . The iPhone wasn’t the first smartphone, but it was the first phone really designed as a primary way to access the Web regularly.”

The other thing the iPhone got right was timing. By the time the iPhone debuted, mobile Internet access was critical for many people. The iPhone met this need and went on sale just as networks were getting fast enough to support Web-centric smartphones. The first iPhone may not have fully leveraged top network speeds, but subsequent iPhones did. Wi-Fi was pervasive by 2007, giving users another connectivity option when AT&T’s network slowed. People had their home and office Wi-Fi and the 11,000 public hot spots AT&T operated nationwide, including in airports, Barnes & Noble bookstores, and McDonald’s restaurants.10 Apple also capitalized on the fact that consumers had started buying smartphones for personal use. The iPhone’s potential audience was much broader than the business elite.

Apple’s timing caught phone makers flat-footed. At the time, RIM, Palm, Motorola, and Nokia led the U.S. smartphone market, in that order. None of them had anything equivalent to the iPhone. Most of them downplayed the threat in order to reassure their investors, and also because it was not yet apparent the iPhone would succeed. Padmasree Warrior, who was then Motorola’s CTO, published a blog post on Motorola’s website the day after Jobs’s presentation. After complimenting the iPhone’s design, Warrior noted, “There is nothing revolutionary or disruptive about any of the [iPhone’s] technologies.”11 Eight days after Macworld, Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer scoffed at the iPhone’s design and price during a CNBC TV interview. “That’s the most expensive phone in the world,” he said, “and it doesn’t appeal to business customers, because it doesn’t have a keyboard.”12 Around the same time, the Korea Times, an English-language South Korean newspaper, quoted an anonymous Samsung official as saying, “Although we are waiting to see how U.S. consumers will react, we are not impressed by [the iPhone’s] features.”13

In a conference call with analysts later that month, Nokia CEO Olli-Pekka Kallasvuo said the iPhone would “be good for the industry” and wasn’t “something that would in any way necessitate us changing our thinking [about] our software and business approach.”14 RIM’s co-CEO Jim Balsillie made similar remarks in June 2007. “[Apple] did us a great favor, because they drove attention to the [smartphone] space,” said Balsillie. “We think that the attention to [the iPhone] . . . has, quite frankly, been overwhelmingly positive to our business.”15 Ed Colligan, who by that time was Palm’s CEO, had a more measured response. In an April 2007 analyst call, Colligan said, “I think [the iPhone] will reach a slightly different [customer] segment [than] what we’re going after.” But he added, “We’re taking it as a serious competitor [and] competitive threat.”16

Yet to smartphone pioneers, including Hawkins, Canova, and Rydbeck, the iPhone felt like validation. Hawkins had already departed Palm to pursue his true passion, neuroscience, and subsequently founded a data analytics start-up called Numenta. He saw in the iPhone the kind of phone he tried to make in the early 2000s. “Apple broke the floodgates open,” Hawkins says. “Now we had a true handheld computer that wasn’t constrained by carriers.” When Canova first saw the iPhone he remembered the Neon prototype he built for IBM and that phone’s tilt sensor-equipped screen. Canova says he thought, “Wow, they did it. I had this idea way back, but they managed to do it.” Rydbeck, too, felt a deep sense of satisfaction: “I thought, ‘Finally, this product is right; finally, a guy who understood exactly what we wanted to do.’ I was as happy as if it were my own company.”

Nevertheless, the iPhone wouldn’t completely fulfill their vision until it supported third-party applications, a fundamental smartphone qualification. As some research firms noted at the time, the first iPhone’s lack of this capability technically classified it as a very high-end feature phone. “While the iPhone is undoubtedly clever and capable, it is not correct to call it a smartphone,” concluded a January 2007 ABI Research commentary.17

Other smartphones had incorporated apps from outside developers for years, but Jobs opposed the idea. As Isaacson’s biography recounts: “[Jobs] didn’t want outsiders to create applications for the iPhone that could mess it up, infect it with viruses, or pollute its integrity.”18 When he first unveiled the iPhone, Jobs clearly viewed it as a closed device. In an interview with the New York Times, he said: “[Apple] define[s] everything that is on the phone. You don’t want your phone to be like a PC. The last thing you want is to have loaded three apps on your phone, and then you go to make a call and it doesn’t work anymore. [iPhones] are more like iPods than they are like computers.”19

According to Isaacson, Apple executives and board members were early to recognize the value of third-party iPhone apps. In the hopes of swaying Jobs, they enumerated the benefits that consumers and Apple would reap from having a wide array of them. Jobs’s inner circle also stressed the competitive angle. Other smartphone companies, such as Microsoft and Nokia, were courting developers for their platforms. Jobs’s advisers warned him that if Apple didn’t start recruiting too, developers would end up supporting Apple’s rivals.20

By mid-2007, Jobs had softened his stance. In June Apple started encouraging developers to write apps for the iPhone using Web 2.0 standards. This meant developers could employ recent versions of Web coding languages, such as HTML, JavaScript, and CSS, to create Web apps that would run inside the iPhone’s browser, rather than native iPhone apps that users installed on their home screens and could remain active in the phone’s background while users did other tasks.

Apple’s policy eased the way for a broad community of Web developers to create iPhone apps, since they wouldn’t have to learn the intricacies of the phone’s operating system. But the policy also meant iPhone apps would have limited functionality because they would only be active inside browsers and would not work when users were offline or had poor network connections. Developers were vocal about their displeasure. InformationWeek observed, “Even though Jobs says Web-based apps ‘look and behave exactly’ like native apps, some Mac software developers don’t buy it. Words like ‘lame’ and ‘weeeeak’ [have] popped up in response on blogs and message boards.”21

Jobs eventually embraced a compromise: the iPhone would support native apps created by outside developers, but Apple would vet all apps and distribute them exclusively through iTunes to ensure quality. In October 2007, Apple announced it would release a software development kit in coming months. Apple also posted a message on its website, signed by Jobs, that said, “We are excited about creating a vibrant third-party developer community around the iPhone and enabling hundreds of new applications for our users.”22 Apple delivered a beta version of its promised SDK in March 2008 and a final version in July.

The Apple App Store opened on July 10, 2008, 13 months after the first iPhone went on sale and in time for the new iPhone 3G, which Apple billed as “twice as fast at half the price,”23 because it ran on 3G networks and cost $199 to $299. When Jobs introduced the App Store, he told USA Today, “We think there’s never been anything like it.”24 This was, again, a slight exaggeration. Independent app stores such as Handango had been around since the late 1990s or early 2000s, initially distributing PDA apps and later selling ones for BlackBerry, Palm, Symbian, and Windows Mobile. In 2008, Handango offered more than 16,000 smartphone apps through its app portal.25

Apple centralized its app operations tightly around iTunes and the iPhone. It not only built the App Store into iTunes, but also built the store directly into the iPhone, enabling users to quickly discover and enjoy iPhone apps. People simply purchased them with a click—or selected them in the case of free apps—and downloaded them wirelessly over cellular networks or Wi-Fi. At the time, Handango and a company called Handmark had partnerships with some carriers and smartphone makers that placed their app software on select BlackBerry, Palm Treo, Symbian, and Windows Mobile phones. These on-device storefronts let consumers browse and download apps over the air like the App Store, but the latter soon passed them in quality and diversity. Apple’s strict standards and comprehensive software tools, combined with the iPhone’s large, bright screen and intuitive user interface, produced apps that looked better and did more than those of other smartphones.

When the App Store debuted, Jobs called it the “biggest launch of my career.”26 The store boasted more than 550 apps, including big names like eBay, Electronic Arts, Facebook, Major League Baseball, the New York Times, Oracle, and Salesforce. In the first 72 hours after its launch, consumers downloaded 10 million apps. Jobs called the results “staggering” and “a grand slam.”27

By December 2008, the App Store stocked more than 10,000 apps. Many of them were so entertaining that USA Today’s Ed Baig compared browsing apps in iTunes to “trolling through the aisles of a toy store.”28 Games proved to be the most popular, as they still are.

Smartphones have hosted games ever since the IBM Simon. After RIM gave BlackBerrys color displays in 2003, it started loading a game called BrickBreaker onto them. BrickBreaker was just a simple clone of Atari’s Breakout arcade game and involved little more than bouncing a ball into a layer of bricks to destroy them. Nevertheless, BrickBreaker amassed a loyal following of tense executives who depended on it for stress relief. Between 2003 and 2010, Nokia tried to bring a video game console–like experience to smartphones with a mobile gaming platform called N-Gage. N-Gage enabled users to download popular titles such as soccer games branded by FIFA, the international governing body of the sport, onto their phones and compete against other people online. But since N-Gage never achieved mass popularity, the iPhone is widely considered the first smartphone that doubled as a gaming machine.

At the end of the App Store’s first six months, Super Monkey Ball from the Japanese video game publisher Sega was one of the bestsellers among paid apps. The game cost a steep $9.99 and involved guiding a bubble-encased cartoon monkey through mazes. Another game, Tap Tap Revenge, which measured how accurately users could tap out a song’s tempo on their phone screens, attracted even more downloads, because it was free. Social networking, Internet radio, and location-based apps were also highly popular.

The iPhone had become a true handheld computer with a broad range of potential features, just like IBM, Palm, and others had imagined years earlier. With the introduction of the App Store, Apple formed its own, self-sustaining ecosystem between consumers, developers, and the iPhone. Like Japan’s i-mode, the iPhone was really a software and services framework tied to a phone, and it was the iPhone ecosystem that pushed the entire smartphone industry forward. Once again, Apple had caught other smartphone companies on the hop. Within a few months, however, a new rival would emerge, presenting Apple with its first real competition.

ANDROID

Unbeknownst to Apple, Google began developing its own smartphone in 2005. The project stemmed from a 2002 meeting at Stanford University between Google’s cofounders, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, and Andy Rubin, an engineer with a deep interest in robotics and mobile technology.29 Rubin began his mobile software career in the early 1990s, when he helped develop the PDA operating system and user interface Magic Cap at General Magic, a start-up Apple had spun out as a separate business. Several big-name companies, including Motorola and Sony, produced Magic Cap PDAs, which won attention for their sophisticated graphics and built-in wireless data connections but struggled in the marketplace.

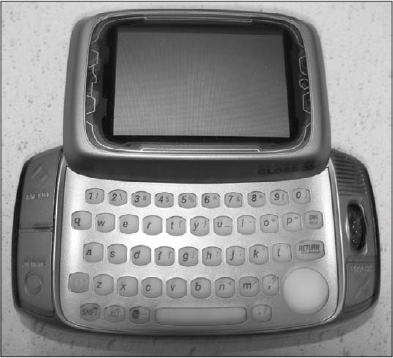

Rubin drew upon that experience in 1999 when he cofounded a start-up, Danger Research Inc., which designed a smartphone platform called hiptop and a trendy series of smartphones that T-Mobile sold under the name T-Mobile Sidekick. Rubin wanted Sidekicks, or hiptops, as they were known internally, to be consumer versions of BlackBerrys—cheaper and more entertaining but similarly data-centric.30 When T-Mobile began selling Sidekicks in October 2002, they were one of the first smartphones to feature always-on cellular data—the GSM/GPRS connections RIM and Handspring had raced to incorporate into their devices. Danger leveraged two-way data to let users send and receive e-mail and chat over instant messaging services anytime, anywhere.

Original Danger Hiptop/T-Mobile Sidekick (David Mueller/Wikimedia)

Sidekicks spearheaded a number of other significant smartphone features, including an on-device app store. Starting in 2004, Sidekicks shipped with a built-in program called the Download Fun Catalog that featured apps, wallpapers, and ringtones, complete with descriptions and screenshots, and enabled users to download them straight to their phones. The charges showed up on their phone bills. “We knew that third-party software would be critical to our success, so we made it easy [to buy and sell apps and install them],” explains Chris DeSalvo, who was a senior software engineer at Danger from 2000 to 2005. “No extra setup, no hassle.” Though more limited in scope than the iPhone’s App Store, the Download Fun Catalog had the same basic functionality, four years earlier, and people actually used it. DeSalvo says some Sidekick developers made $40,000 or more per month off app sales in the catalog’s early years.

Sidekicks were also one of the first phones that let users wirelessly synchronize and save their phone data to an online account. Danger’s cloud storage system automatically saved everything users did on their hiptops, which enabled them to manage far more data, such as e-mails, than their phones would have been able to hold on their own since smartphones didn’t have much storage capacity at the time. “By having our servers hold it all we enabled the hiptop to dynamically flush old stuff out and pull new stuff in, knowing that we could always do another shuffle later on, if you needed to see that old stuff again,” says DeSalvo. This service had hiccups, including a 2005 hack of personal data from socialite and Sidekick user Paris Hilton’s account and a 2009 server outage that erased user data. But many consumers liked the idea of backing up their phone data in case of phone loss, theft, or damage and other smartphone companies later introduced similar services.

Though Sidekicks blazed a trail, they were never broadly popular and still don’t get much recognition for their innovations. DeSalvo thinks distribution, marketing, and most of all timing curbed the phones’ sales—and, consequently, their legacy. “We were just too early,” he says. “We had all this great stuff, and no one had any idea that they wanted or needed it.” It didn’t help that T-Mobile largely marketed Sidekicks to teens. “The hiptop was presented as a cutesy fashion accessory for kids rather than a powerful tool that could unchain you from your desktop computer,” laments DeSalvo.

In 2003, Rubin left Danger and cofounded Android Inc. The initial plan was to create a software platform that would let users move photos off their digital cameras and store them in the cloud, but the start-up decided to develop an “open-source handset solution” after realizing phones were a far larger target market than cameras.31 Larry Page, who was interested in mobile technology, had kept in touch with Rubin following their meeting at Stanford, and in 2005, the two met to discuss Android. Soon after, Google quietly acquired the start-up, reportedly for $50 million,32 making Android a wholly owned subsidiary.

Still, Android operated so stealthily that rumors of a Gphone didn’t surface for more than a year. In December 2006, The Observer, a British newspaper, reported that Google had met with Orange to discuss a “branded Google phone” with “built-in Google software.”33 In March 2007, a Boston-based technologist with “an inside source” blogged that Rubin was building a “BlackBerry-like, slick device” with a 100-person team.34 Speculation escalated, with many believing Google was creating a no-cost, completely ad-supported phone. In September 2007, the Los Angeles Times noted, “The Google phone is like the Roswell UFO: Few outsiders know if it really exists, but it has a cult following.”35

Google tried to quiet this speculation in November 2007 by announcing the creation of Android and the Open Handset Alliance. Google characterized Android as “the first truly open and comprehensive platform for mobile devices,”36 because it would be free and available to anyone who wanted to use it, and could be customized. The alliance was a coalition of 34 technology companies, including Google, other software providers, manufacturers, and carriers that would collaborate on Android with a “common goal of fostering innovation on mobile devices.”37 Google executives emphasized that the new operating system, based on the free, open-source software Linux,* would “power thousands of different phone models.”38 This disappointed those anticipating an iPhone-like Gphone. An Advertising Age article bemoaned “the fact that the Google Phone turned out to be not an actual phone but just a giant nerd committee.”39

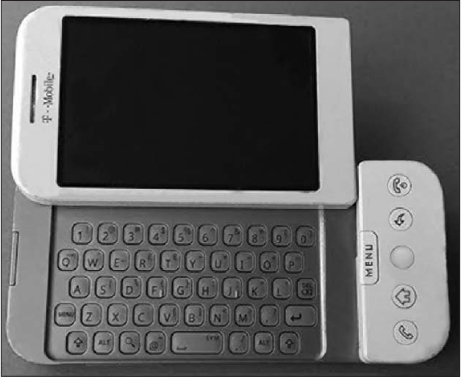

The public wouldn’t see the first Android phone until September 23, 2008, when a launch event was held in New York City. By that time people knew the mythical Gphone was real, because most of the major details had leaked, including the phone’s name (G1), manufacturer (HTC), exclusive U.S. carrier (T-Mobile), and basic design (large touchscreen with slide-out QWERTY keyboard and a trackball for navigation). As expected, the G1 integrated multiple Google properties, such as Gmail, Google Calendar, Google Maps, Google Talk instant messaging, Google Search, and YouTube. A speedy, full-fledged Web browser and the user’s Google account tied everything together. “Suddenly, the hodgepodge plethora of Google applications and services have a single point of connection and synchronization,” reported eWEEK.40

T-Mobile G1, the first Android smartphone (Elizabeth Woyke)

The G1 went on sale in late October, priced at $179, $20 less than the iPhone. Early reviews tended to applaud Android, find fault with the phone’s hardware, and critique T-Mobile, which was still rolling out its 3G network nationwide. David Pogue, the former New York Times technology columnist, gave the G1’s software an A– (“smartly designed”), the hardware a B– (“thicker, heavier and homelier than the iPhone”), and T-Mobile a C (“one of the [country’s] weakest networks”).41

Comparisons to the iPhone were inevitable. A New York Daily News headline read, PHONE FIGHT! T-MOBILE TEAMS WITH GOOGLE TO TAKE ON APPLE’S KINGPIN.42 But the iPhone easily beat the G1 on most counts. Virtually no one preferred the G1’s bulky design to the iPhone’s unless they were big fans of built-in keyboards. Google’s mobile app store, then called the Android Market, also rated low marks. It debuted on the same day as the G1 with far less polish than the App Store. The Guardian described the market’s assortment of about 50 apps, few of which came from big brands, as “desperately thin.”43

Unbeknownst to the public at the time, the G1 was Google’s Plan B. Google originally aimed to introduce its first Android phone in late 2007 but postponed the release after seeing Jobs’s unveiling of the iPhone. As journalist Fred Vogelstein details in his book Dogfight: How Apple and Google Went to War and Started a Revolution, Rubin and his team intended to launch Android with a small-screen, QWERTY-keyboard phone, but when they saw the iPhone’s multitouch screen, they realized they too needed to offer a touchscreen and shifted their efforts to a different phone that became the G1.44

Google’s governing idea for Android remained the same: to create an operating system that would appeal to anyone who used Google services. DeSalvo, who joined Android as a senior software engineer in 2005, says: “We wanted the G1 to be a seamless extension of the relationship you already had with Google [on your computer]. You should be able to start a draft Gmail on your desktop, walk away, pick it up later on your G1, finish editing, and send it. A chat you were having on your desktop in Google Talk should be right there on your phone, [too].”

The iPhone couldn’t do this type of fluid, over-the-air data syncing, but the iPhone’s stylishness made the Android team nervous. “The scrolling [on the first iPhone] was supersmooth, the colors were great, the icons and typography were gorgeous,” DeSalvo recalls. “Visually, the software we had at the time was nowhere near as good.” The contrast between the two phones and platforms was obvious: the iPhone was “an extremely beautiful realization of a very limited device” while Google’s Android prototype was “a much uglier realization of a very powerful device,” he says.

The Android team knew first impressions mattered to consumers. To compete, Android would have to exploit features the iPhone couldn’t or wouldn’t offer: tight coupling with a user’s Google accounts and broad uptake across multiple carriers. “Google already had insane numbers of users. If we could convince just a few percent of them to get an Android phone, then we’d be a huge success,” adds DeSalvo.

Android took time to catch on, and the G1 wasn’t an iPhone-level hit. The first iPhone sold 1 million units in 74 days. The iPhone 3G passed that mark in three days. It took the G1 about six months to cross that line. But its integration of Google services, its speed, and the ability to customize it gave the G1 a unique appeal. CNET wrote, “In a battle of pure looks, Apple’s iPhone would win hands down, [but] the real beauty of the T-Mobile G1 is the Google Android platform, as it has the potential to make smart phones more personal and powerful.”45

Like the iPhone, Android borrowed from its predecessors. The G1’s large touchscreen was an obvious reference to the iPhone, but the phone also had hiptop DNA. Its slide-out keyboard resembled the Sidekick’s, and not by coincidence. “All of us loved our hiptop keyboard,” DeSalvo says. “We had put a lot of work into its design [and figured out] what makes a really great thumb keyboard.”

Android also incorporated software notifications, which had been another hiptop innovation. Prior to Sidekicks, most mobile devices besides BlackBerrys didn’t have a good way to tell users they had new voicemail or remind them of an upcoming appointment. On Sidekicks, notifications subtly appeared at the top of phone’s screen to inform users of missed activity. For the G1, DeSalvo and his colleagues improved on that system by adding a virtual “window shade” that listed notifications, which users could pull down from the top of the phone’s screen with their finger. Other smartphones, including the iPhone, would later adopt this feature.

Google designed the G1 to convey its philosophy about smartphones. Google wanted mobile technology to emulate the more open world of the desktop computer and Internet. Whereas the iPhone and App Store were a “walled garden” carefully tended by Apple, users and developers would rule Android and the Android Market. “By making a lot of the source code free for others to use we knew that it would get picked up and used in ways we couldn’t think of,” says DeSalvo. That, in turn, would benefit Google’s corporate interests as a search and advertising provider. The Open Handset Alliance and Linux were key parts of this strategy.

FROM LAGGARD TO LEADER

The ascendancy of the iPhone and Android, and the speedy adoption by U.S. carriers of a fast, fourth-generation (4G) wireless data standard, called Long Term Evolution (LTE), repositioned the United States as the center of smartphone innovation, with Silicon Valley as the new capital of the smartphone world. In 2012, the then–FCC chairman Julius Genachowski trumpeted these developments in a speech that said the United States had gone “from laggard to leader” in mobile technology.46 He said:

Four years ago people were talking about mobile innovation in Asia and mobile infrastructure in Europe and describing the U.S. as a backwater. Today the U.S. is the clear world leader on mobile innovation. U.S. companies invented the apps economy, and in four years the percentage of mobile devices globally with U.S.-made operating systems has grown from twenty percent to eighty percent. On mobile infrastructure, the U.S. is now leading the world in deploying at scale the next generation of wireless broadband networks, 4G LTE. . . . Today the U.S. has more LTE subscribers than the rest of the world combined, and we’re on a path to maintain leadership into the future.

The changes the iPhone and Android wrought were more than geographic. Smartphones had always had more features than basic cellphones and feature phones, but after the iPhone and Android gained momentum, smartphones needed to be true mobile computers to compete effectively in the market. For many smartphone makers this shift required jettisoning their operating systems. Older platforms couldn’t match Apple and Google’s software prowess, which made it challenging to sell phones and entice third-party developers to write apps. These companies had to either align themselves with Google and Android or build their own mobile computing platforms. Companies that chose the latter needed to develop that software as quickly as possible while still selling and supporting phones based on the software they were phasing out. It was a tricky maneuver, and many smartphone companies fumbled the transition. Some that had led the industry in the early 2000s would cease to exist just a few years later.

One company that decided to take on Apple and Google was Microsoft. Around 2009, Windows Mobile was losing developer and licensee support in part because it couldn’t match the iPhone or Android in aesthetics or ease of use. Windows Mobile didn’t support multitouch, and it felt clunky on regular touchscreen phones. As the Guardian observed at the time, Windows Mobile “has an image problem. . . . [T]he Windows phone platform has been regarded as a dull tool for corporations instead of a strong player in the consumer market, and its user interface has never been much to write home about.”47 Or as tech reporter Dan Frommer put it, “[It] isn’t that Microsoft didn’t see the mobile revolution coming. It just peaked way too early, and wasn’t prepared when Apple showed up with something a lot better.”48 Microsoft realized it needed to start coding a new solution from scratch rather than continue to tweak its mobile software. In 2010 it scrapped Windows Mobile and introduced more modern software. To highlight its break with its past, Microsoft rebranded its smartphone software yet again, this time calling it Windows Phone.

Meanwhile, Nokia’s global reach kept Europe, Symbian, and itself at the top of the smartphone sales charts until 2011, but it started to sputter after Android’s release for some of the same reasons as Windows Mobile. Symbian’s code was bloated from years of additions and revisions, causing app developers to shun it. Nokia had also steered Symbian away from supporting touchscreens, which left Nokia playing catch-up once smartphones became synonymous with multitouch technology. Under a new CEO, Stephen Elop, Nokia started phasing out Symbian in 2011 and adopted Windows Phone as its smartphone operating system. The Symbian misstep cost Nokia its smartphone crown, and by 2013 Nokia had slipped to number ten in global smartphone sales.

In September 2013 Microsoft announced it would pay $7.5 billion to purchase Nokia’s smartphone and cellphone business, and to license Nokia’s patents and mapping services for 10 years. Nokia is now a very different enterprise, one focused on developing and selling telecommunications network infrastructure, mapping and location services, and advanced wireless and Web technologies—not phones.

Nokia’s decline and Windows Mobile’s weakness gave Android an opening. “Once those two platforms fizzled out, Android was the obvious choice to fill the vacuum,” says DeSalvo, the former Android software engineer.

About a decade after introducing the R380, Ericsson exited the cellphone business. Over the years, its focus had shifted to selling telecom equipment and services. Designing consumer phones was a better fit for its handset partner, Sony, which acquired Ericsson’s share of their joint venture in 2011 and turned Sony Ericsson into a Sony subsidiary. Sony CEO Kazuo Hirai has said he wants mobile products, including smartphones, to be one of the company’s three main growth areas for the future.

Palm ceased to exist in 2011. In 2009, Palm rallied one last time, producing a well-respected operating system, webOS, and some interesting new phones. But the phones didn’t sell well, and HP acquired a financially ailing Palm in 2010. Following management changes, HP killed off the Palm brand in 2011 and sold webOS to LG in 2013, which it uses in smart TVs.

Motorola split into two companies in 2011. The part of Motorola that makes two-way radios and voice and data systems for government agencies and corporations became Motorola Solutions. Motorola’s consumer phone business, which had struggled for years to develop a successor to its best-selling Razr cellphone, became Motorola Mobility. Google announced its plan to acquire Motorola Mobility later that year and attempted to return Motorola to profitability for about a year and a half, but in January 2014 sold it to Chinese computer maker Lenovo for $2.91 billion.

BlackBerrys lost much of their allure once e-mail and instant messaging became standard smartphone features. In the 2010s, RIM weathered a series of major changes, starting with the appointment of a new CEO in early 2012; Lazaridis and Balsillie resigned, and Lazaridis retreated to a board role, then completely left the company in 2013 (Fregin had retired as a vice president in 2007). That year RIM also changed its name to that of its better-known brand and introduced a long-awaited operating system, BlackBerry 10, and several BlackBerry 10–based smartphones. The software won a decent amount of praise, especially for its virtual keyboard. So did RIM’s first flagship BlackBerry 10 phone, the touchscreen Z10.

However, both products arrived too late to reverse BlackBerry’s fortunes. BlackBerry posted dismal results for two consecutive quarters in 2013, including a $965 million loss for its fiscal second quarter. That August BlackBerry announced it was exploring “strategic alternatives,” including a sale of the company.49 Lazaridis and Fregin expressed interest in buying it, and rival technology firms offered to purchase some of its assets, such as its patent portfolio, but BlackBerry ultimately accepted a $1 billion cash infusion from a small group of its institutional investors to cover its short-term financing needs. As the New York Times wrote in November 2013, “[BlackBerry] will either fail miserably or be a remarkable turnaround. . . . [The $1 billion] investment . . . buys BlackBerry more time for an overhaul.”50 The investment deal ushered in yet another CEO—a seasoned enterprisetechnology executive named John Chen, who has pledged to return BlackBerry to profitability by early 2016 with a renewed focus on serving companies and the government.

THE EMERGENCE OF SAMSUNG

As technologies and trends change, errors trip up the seemingly infallible, and companies exploit their rivals’ weaknesses, new leaders have come to the fore in the smartphone market. One success story is Samsung, which went from holding just a 3 percent sliver of the global smartphone market at the end of 2009 to 10 percent a year later, and continued to grow until early 2014.

Originally a food-trading business that branched into sugar and textile manufacturing, Samsung entered the electronics industry in 1969 when it established Samsung-Sanyo Electronics as a joint venture with the Japanese electronics maker Sanyo. In the 1970s, after Sanyo divested its shares in the joint venture, it became Samsung Electronics, and by the 1980s it was creating cellphones for the Korean market and harboring aspirations of becoming the world’s largest electronics company.51

Network technologies helped Samsung establish itself as a global cellphone maker. Korea was one of the few countries outside the United States that decided to deploy CDMA for its 2G networks. Since CDMA wasn’t widespread, only a handful of companies in the world produced CDMA phones in the mid-1990s, and in 1996 this lucky coincidence led Sprint to offer Samsung a $600 million contract to provide cellphones for its CDMA network.52 The Sprint deal was Samsung’s introduction to the U.S. cellphone market. Korea’s manufacturing expertise, which the government began fostering in the 1970s to compensate for a lack of natural resources, also helped Samsung’s ascent.

Samsung released a device widely regarded as its first smartphone, a Palm OS PDA-phone hybrid called the SPH-i300, in 2001. Over the next few years Samsung produced a rapid succession of smartphones that enabled it to experiment with software and design. In 2004, it became the first phone maker to offer handsets based on the three major smartphone platforms at the time: Palm OS, Microsoft’s Windows Mobile, and Symbian. Around this time, too, Korea became a thoroughly connected society, with some of the world’s highest Internet and cellphone usage rates and fastest wire-line and wireless speeds. These advances gave Samsung “a great test-bed” for mobile devices and features before exporting them, says Kim Yoo-chul, a technology reporter for the Korea Times.

Samsung stumbled at first with iPhone-style smartphones, but started catching up in 2009, when the Korean government lifted restrictive mobile software and wireless Internet regulations that had stymied smartphone development and adoption. In 2010, Samsung finally broke through with its Galaxy S handsets, which were thin, fast, and had global carrier support. There was a market need for an iPhone competitor, and Samsung delivered it. As a 2013 New York Times article made clear: “Apple, for the first time in years, is hearing footsteps. The maker of iPhones, iPads and iPods has never faced a challenger able to make a truly popular and profitable smartphone or tablet—until Samsung Electronics came along.”53

* Linux software was initially developed as a PC operating system and now runs everything from computer servers to supercomputers to gadgets, and is supported by the donated efforts of thousands of programmers around the world.