On a chilly night in March 2013, more than 3,000 people gathered in Radio City Music Hall to watch Samsung introduce its Galaxy S4 smartphone. There was an electric feeling of anticipation inside the New York City theater as JK Shin, the head of Samsung’s mobile division, emerged from behind a curtain. Striding to the middle of the hall’s giant stage, Shin did his best to deliver a Steve Jobs–style pitch for Samsung’s latest flagship phone. After highlighting the Galaxy S4’s distinctive features, including a “touchless” interface that let users navigate the phone using hand gestures and eye tracking, Shin touted the phone as a life-changing device: “Once you spend time with the S4, you’ll realize how it makes your life richer, simpler, and fuller.”

To reinforce Shin’s message, a troupe of actors took the stage. Over the next hour the actors, backed by a full orchestra, performed a series of skits showing off the S4’s features, from its voice recognition to its health-tracking software. And besides the thousands in the hall, hundreds of people attended a “viewing party” in Times Square to watch the unveiling on gigantic billboards and more than 410,000 people tuned in to the YouTube feed to watch the event live-streamed.

Most smartphones debut at small press conferences. Apple’s product launches are larger affairs, but they are still limited to reporters and analysts and held in a local convention center. Samsung unveiled its first Galaxy smartphone, the Galaxy S, at a 2010 Las Vegas trade show; the Galaxy SII in Barcelona, at a different trade show; and the Galaxy SIII at a London exhibition center. With the Galaxy S4, Samsung pulled out the stops. For Samsung, the event wasn’t just about a device. It was the Korean company’s chance to beat Apple on Apple’s home turf. Samsung booked a famous location and hired actors, writers, and producers to put on a show in an attempt to one-up its biggest competitor.

Mixed reaction kept the Galaxy S4 launch from being a triumph. There was a near universal dislike for the skits, which were packed with embarrassing jokes. People were divided on the phone’s merits as well. Nevertheless, the consumer and media buzz generated by the launch—and the hype that preceded it—cemented Samsung’s position as Apple’s most serious smartphone competitor. The New York Times called the launch “a challenge in iPhone’s backyard.”1 AllThingsD (now Re/code) wrote, “It’s usually Apple, not Samsung that gets this kind of attention.”2 Barron’s said, “Samsung’s latest shot in the smartphone wars . . . debuted with a loud bang.”3

Selling smartphones is one of the fiercest fights in global business today. We talk about smartphone wars because the smartphone industry has become a battlefield for the world’s technology giants, which scuffle to stay ahead, and sometimes just to stay in business. These companies brawl daily, on multiple fronts, both in the courtroom and in the public eye. They pour millions of dollars into lawsuits and ads attacking each other, looking for any way to gain ground. The companies themselves use warlike terminology when discussing their competitors. Steve Jobs talked about “go[ing] to thermonuclear war”4 on Google for allegedly copying Apple’s technology and also referred to engaging in a “Holy War”5 competition with Google, on a number of fronts, including Android. Jobs’s successor, Tim Cook, vowed to “use whatever weapons we have at our disposal”6 to protect Apple’s intellectual property.

The smartphone wars are intense because the market is large and lucrative. Estimates of its size range between $250 billion and $350 billion, which is larger than the PC market and more than twice as large as the Internet advertising market, although both of those markets existed years before smartphones. Smartphones also outsell PCs by a factor of more than three to one in terms of units, even though PC shipments outnumbered those of smartphones as recently as 2010. With a billion new smartphones shipped to retailers annually, market researchers say the smartphone industry is growing 19 percent each year, while growth in the PC market declines year over year. Smartphones are also outselling basic phones globally, having accounted for 55 percent of all cellphone shipments in 2013.

Smartphones aren’t just a huge market; they can also be far more profitable than most other tech products. Their profit margins are high because smartphone makers can command lofty prices for their devices while reducing their production and distribution costs through large volumes. The iPhone is Apple’s biggest moneymaker, accounting for more than half of the company’s 2013 revenues. Analysts estimate Apple’s iPhone gross product margins are between 40 percent and 50 percent.* In contrast, gross margins for Apple’s other products, including the iPad, iPod, and Mac computers, hover between 20 percent and 30 percent, either because they are relatively more expensive for Apple to produce or because Apple sells popular, more affordable versions of those products, such as the iPad mini. Samsung’s gross margins are lower than Apple’s but show a similar gap between phones and other gadgets. Samsung’s phone business is so lucrative, it accounts for two thirds of the company’s total operating profit.

Naturally, smartphone companies want to protect their high profits. They also recognize that smartphones are the future of the Internet, computing, communications, advertising, and shopping. Failing in the smartphone market means losing influence in multiple important industries, and these high stakes fuel the smartphone wars.

ANDROID VERSUS APPLE

Hundreds of companies participate in some way in the smartphone economy, from contract manufacturers to gadget recyclers. The main players are the platform (operating system) providers, the smartphone makers, and the carriers. The leading carriers usually differ from country to country, but the platform providers and the major phone makers operate on a global scale. Among those global players, there are three main combatants: Apple, Google, and Samsung. Apple and Google power the most smartphones through their respective operating systems, iOS and Android, while Apple and Samsung sell the most smartphones.

Apple and Google together control 94 percent of the global smartphone market. Android holds 79 percent of the market and iOS has 15 percent. (In the United States, the split is 51 percent Android, 44 percent iOS.) More than 1.5 million Android devices, the majority of which are phones, are activated every day, while 794 million Android phones shipped to retailers in 2013. Apple sold 150 million iPhones in 2013. iOS initially led Android because it had a year’s head start, having debuted in 2007 with the first iPhone, but Android passed iOS in phone shipments in mid-2010.

Apple and Google have different business priorities for their smartphones. Google, at its core, is an online advertising company. It has three main business goals: to increase the number of places it can run ads; to show those ads to as many consumers as possible; and to collect and mine consumer data to improve its ads. Android helps Google do all three. Search for a business within Google Maps on an Android phone and an ad will appear at the bottom of the screen. Google earns money by serving up this data, and it earns even more if consumers engage with the ad by, for example, clicking a link to call the business.

Android devices give Google a direct route to consumers. Since Google’s Android partners preinstall its services on their phones, the operating system serves as a defense against companies that might try to inhibit Google’s access to consumers on mobile devices, says Horace Dediu, a technology analyst who runs his own consultancy called Asymco. Before the iPhone launched, Google was concerned about Windows Mobile dominating the mobile industry, so that smartphones would default to Internet Explorer and other Microsoft services, leaving no room for Google’s properties. After the iPhone launched, Google worried about being overly dependent on Apple for mobile traffic. Android creator Andy Rubin has said that, pre-Android, “it was very, very hard to get Google services in front of the faces of users on cellphones.”7

Google measures Android’s success by the number of users it reaches. To encourage device makers to use Android, Google makes the software high quality, free, and easily malleable. In a market as diverse and price sensitive as smartphones, this is a recipe for instant popularity. But Google also imposes more rules on device makers than outsiders might assume, given its many statements about openness. Phone makers that want to use the Android name, preinstall Gmail, Google Maps, YouTube, and other Google services on their handsets, or use Google’s development tools, which support in-app features such as billing for purchases, user geolocation, and messaging, must comply with Google’s compatibility requirements, which are basically tests that ensure Android apps will run smoothly on the devices. Preloading one Google service also means preloading all of them; phone makers can’t take Google Maps but pass over Google+, Google’s social networking service. This makes Android, in technology writer Steven Levy’s words, “a gateway drug to Google products and ads.”8 Google’s Open Handset Alliance phone partners further agree not to employ Android in unauthorized ways, such as “forking” Android to create noncompatible versions of the code or manufacturing devices for software companies that have forked Android. Google recently added another requirement: that new Android phones display the words, “Powered by Android,” on the bottom of their screens when they are activated. Device makers that reject these conditions can use the open-source version of Android but will have to find their own replacements for Google’s signature services and software tools.

One of Google’s most important licensed apps is its online marketplace, Google Play, which replaced the Android Market in 2012 and sells apps, songs, books, and videos. Like other platform providers, Google takes a cut of each paid app sale, but it distributes much of its earnings to its carrier and phone maker partners, reducing the amount it pockets.

Google values Android apps because they help it sell ads, which contribute the “vast majority”9 of its mobile revenues. Calculating what that means and the amount of money Google makes off Android specifically is tricky. Android is presumed to be profitable as a Google business division (based on advertising generated through Android). Rubin said it was in a 2010 AllThingsD interview,10 and Android has grown exponentially since then. But Google doesn’t break out mobile ad sales in its financial results and rarely discusses them in detail during its earnings calls. The most recent occasion when Google specified its mobile revenues was in October 2012, when it said it had a “mobile run rate”11 of $8 billion a year. Based on that number, analysts estimated the company pulled in approximately $5 billion a year from mobile ads and services across all smartphones (not just Android).12 Google’s mobile revenues have increased since October 2012, but it’s not clear by how much. For example, in June 2013, Google said a new video ad format helped YouTube triple its mobile revenues since late 2012.13 Bloomberg quoted an analyst who estimated this meant Google was reaping as much as $350 million from YouTube mobile ad revenues per quarter, but Google did not specify an amount itself.

Much of Google’s mobile ad money is believed to come from iOS, since Google is the default search engine on the iPhone. Advertisers generally pay higher rates to reach iPhone users, because iPhone users are more likely to engage with mobile marketing campaigns and make purchases on their phones, according to the marketing data provider comScore.14

If Google measures its success through advertising, Apple’s core business is selling mobile devices. Like Google Play, Apple’s App Store isn’t a major profit source for the company. Says Dediu, “iTunes is to Apple what Android is to Google—a business not designed to make money in and of itself but to sustain another business.” The App Store is expensive to operate because Apple pays not only for the technology infrastructure, Web hosting, and payment processing but also for the army of people it employs to inspect apps and communicate with developers. “Apple considers the quality of its app offerings to be very important, so it invests a lot into app certification, which is very costly,” says Michael Vakulenko, strategy director at the London-based market analysis firm VisionMobile. VisionMobile has estimated that, on average, it costs Apple about $2,500 to put an app in the App Store, regardless of whether it is a free or paid app.

The flagship iPhone is Apple’s profit engine. Apple is believed to pocket more than $200 in profit from each one, due to efficient manufacturing and high sales prices. Apple also leverages its size and cachet to squeeze low prices from component makers and other suppliers. It also rigorously limits the number of iPhone models it sells. By mostly restricting its smartphone offerings to its three most recent models—for instance, the flagship iPhone 5S, the cheaper iPhone 5C, and the older iPhone 4S—it can exploit economies of scale in sourcing and manufacturing.

Sales to carriers are the other half of the iPhone profit formula. Though other smartphone makers charge carriers a discount wholesale rate for their phones, Apple demands full price. Carriers pay about $650 for every flagship iPhone they purchase. Apple also forces carriers to buy a certain number of iPhones in a given time period. For example, in 2011, Sprint agreed to purchase $15.5 billion worth of iPhones over four years in exchange for the right to finally sell the device.15 Carriers loathe Apple’s tough terms, but most acquiesce to its conditions because the iPhone is incredibly popular with consumers, and iPhone users buy expensive mobile broadband plans, which ultimately help the carriers.

Carrier support has helped keep the iPhone’s price sky-high for years—a rare occurrence in an industry where smartphones generally experience dramatic price drops a few months after launch. By 2011, Apple was so flush with iPhone and iPad profits, it passed oil and gas company ExxonMobil to become the world’s most valuable company by market capitalization. ExxonMobil retook the title in the spring of 2013, but Apple has since managed to reclaim the market-cap crown, in part due to ExxonMobil’s own challenges, including higher production costs for oil and natural gas.

In 2013, Apple introduced the iPhone 5C, which was $100 more affordable than previous iPhones, and in 2014, it launched a version of the handset that was $70 cheaper, with a smaller amount of internal memory, in major markets outside the United States. But Vakulenko doesn’t think Apple will unveil a truly low-cost iPhone for a few years, because Apple prizes product quality and profitability above market share. As Tim Cook likes to say, “We have never been about selling the most.”16 Instead, Apple creates value for iPhone users by maintaining an ecosystem that connects developers to consumers. Vakulenko says that as long as that ecosystem is large enough to sustain itself and be competitive with that of Google’s Android, Apple won’t worry about the need to introduce a low-cost iPhone. “It’s a delicate balance,” Vakulenko explains. “Apple is trying to optimize profit, so it will go as low as it thinks it can go [price-wise] to satisfy the needs of its [ecosystem], but it will also stay as high as possible to keep the company hugely profitable.”

ECOSYSTEM WARS

Most people think of the smartphone wars as individual companies and phones competing head to head, but the industry is also a war of ecosystems. Apple and Google both operate self-reinforcing ecosystems based around apps. These ecosystems helped Apple and Google grab power within the smartphone industry several years ago, and now help them preserve their power.

The iOS and Android ecosystems function essentially the same way. They link two groups that normally have difficulty communicating: developers and consumers/users. The groups feed each other, and the resulting sales feed Apple and Google. More precisely, the large number of iOS/Android apps attract users. Those users attract new developers and encourage them to produce apps. Those apps then attract new users to iOS/Android. It’s a positive feedback cycle that benefits the entire ecosystem, particularly the ecosystem owners, Apple and Google.*

Vakulenko says these “network effects” are found in all computing systems. Computing companies have welcomed developers and third-party apps since the 1980s. As a computer maker, Apple understood the strength of this model though Steve Jobs initially resisted the idea of opening up the iPhone. As a provider of cloud computing and Internet-based services, Google also understood it. Smartphone makers without computing experience, such as Korea’s LG and Motorola, grasped the concept late. Other phone makers established ecosystems relatively early, but they weren’t app-based. Vakulenko says the BlackBerry ecosystem mostly connected BlackBerry users to each other through messaging technology, and Nokia’s Symbian ecosystem mostly served the needs of phone makers and carriers. Since those ecosystems didn’t foster the development and distribution of apps, they didn’t catch on like iOS and Android did.

Successful smartphone ecosystems flourish for years. Network effects enable these ecosystems to grow exponentially. Strong ecosystems, such as iOS and Android, further lock in users by selling them smartphone accessories. People who spend money within a smartphone ecosystem are less likely to defect to competing platforms, because they don’t want to give up their purchases. Habits are also hard to break, and people build up comfort and familiarity with the way their smartphone platforms are designed and operated. To lure these consumers away a new ecosystem has to match those apps and accessories as well as offer something uniquely appealing.

Smartphone ecosystems also lock in developers by convincing them to invest considerable time and effort learning their specific coding languages and business systems. “There’s a complex set of issues developers need to master on a new platform, from how to use [software tools] to how to monetize their apps,” says Vakulenko. “Once developers get proficient, they need a very, very good reason to jump somewhere else and learn again from scratch.” The most popular ecosystems, such as Android and iOS, also provide developers with useful tools, such as ways to translate their apps into foreign languages. In smaller ecosystems developers have to handle these tasks themselves or forgo them entirely.

These high switching costs have kept users and developers loyal, forging iOS and Android into smartphone empires that can ward off upstart ecosystems that try to replace them. So far, only one newer ecosystem has managed to gain a foothold, and it’s a small one. Windows Phone is the industry’s distant number three, with about 3 percent of global smartphone sales.

Windows Phone faces an uphill battle. Timing is a crucial factor in the smartphone wars, and Windows Phone was a few years behind the competition. By the time Microsoft phased out Windows Mobile and brought Windows Phone to market, it was late 2010. iOS and Android had already rounded up and locked in droves of consumers and developers. Also, until early 2014 Microsoft monetized Windows Phone through licenses to phone manufacturers, reportedly charging companies including HTC and Samsung somewhere between $5 and $15 for every Windows Phone handset they sold. This business model put Microsoft at a disadvantage in an Android-dominated world. “Smartphone vendors are already squeezed so much trying to get costs down,” says Dediu. “On top of that, you have Microsoft saying you have to pay this license. The alternative is Google, who says, ‘You don’t have to pay for Android, which is just as good, if not better.’”

Windows Phone managed to pick up momentum anyway, in part because of RIM/BlackBerry’s decline. Windows Phone was the world’s fastest-growing smartphone operating system in 2013 (though it also started from a much smaller base), and it accounted for more than 10 percent of the smartphone market in some European countries by early 2014, thanks to Nokia’s historic strength in Europe. Nonetheless, in April 2014, Microsoft took the dramatic step of making Windows Phone free for smartphone makers. Microsoft appeared to realize that nothing short of free distribution would enable it to grow the Windows Phone ecosystem beyond itself and Nokia, whose cellphone and smartphone business it was on the brink of absorbing.

The big question is how Microsoft plans to make money off Windows Phone now that it is giving it away. Microsoft’s new CEO, Satya Nadella, who succeeded Steve Ballmer in February 2014, frequently talks about how he is directing the company to embrace a “mobilefirst cloud-first” world. Vakulenko approves of that plan, as it shifts Microsoft’s focus from “the stagnating PC business” to “high-growth areas.” PC shipments have been sliding since mid-2012 and posted their largest-ever annual decline (of 10 percent) in 2013. But Vakulenko maintains that “it is not clear how exactly Microsoft will . . . build a profitable business in these areas.” He notes that successful smartphone platform providers either use services to increase the value of their devices (Apple) or commoditize devices to achieve the widest distribution possible of their services (Google). Microsoft is pursuing a different strategy that uses devices to sell cloud-computing services, such as its online Office 365 service. Nadella has said the company’s new mission is to “deliver the best cloud-connected experience on every device.”17

Even if Microsoft fails to establish Windows Phone as a major growth market, it will probably continue to fund Windows Phone to bolster its ecosystem. In a 2013 PowerPoint presentation it posted online that outlined its “strategic rationale” for acquiring Nokia, Microsoft wrote: “Success in phones is important to success in tablets” and “Success in tablets will help PCs.”18 In other words, Microsoft believes a person who buys a Windows Phone is more likely to buy a Windows tablet and a Windows computer, especially with its recent introduction of “universal” apps that will work across all Windows devices. Tim Cook has said this is true for Apple, stating in 2012, “What is clearly happening now is that the iPhone is creating a halo for the Macintosh [computer]. The iPhone has also created a halo for iPad.”19 In other words, the smartphone wars aren’t just about phones. They’re also about full ecosystems of devices and services.

APPLE VERSUS SAMSUNG

Like smartphone platforms, smartphone manufacturing is a two-horse race. Here, instead of Apple and Google, the two are Apple and Samsung, and they are so far ahead of other phone makers that they currently claim more than 100 percent of global smartphone profits. In the fourth quarter of 2013, Apple took 76 percent of smartphones profits while Samsung took 32 percent, according to the investment bank Canaccord Genuity. Apple and Samsung were able to amass 108 percent of the profits because other smartphone makers lost money or just broke even.

While Apple leads the industry in profitability, Samsung leads in volume. Samsung is the world’s largest smartphone maker by unit sales, selling about 31 percent compared to Apple’s 15 percent. Outside of Samsung and Apple, the market splinters. No other company holds more than a 5 percent share.

Analysts often describe Samsung as a “fast follower” because it sweeps into a market after other companies have laid the groundwork. It has done this for decades, with one book about the company describing its strategy as follows: “Samsung’s main thrust boiled down to picking specific areas to achieve key differentiation, the most successful of which was the mobile cellular phone. Samsung then focused on flooding the market.”20

Even now Samsung floods the market. It has the largest product portfolio of any major smartphone maker, enabling it to attack Apple at the high end of the market and Nokia at the low end. “The Samsung business model is about muscle, not finesse,” says Dediu. “Companies like Apple establish a beachhead and Samsung expands it, then gets out before there’s nothing interesting left.” In the United States alone Samsung offers close to 50 smartphones at prices ranging from $300 to free with a two-year contract. Globally Samsung sells more than 70 different smartphones across three operating systems. “While Apple has [mostly] been sticking to its ‘release one model a year’ philosophy, Samsung took a different path, expanding its lineup from premium to mid- to low-range smartphones,” says the Korea Times’s Kim Yoo-chul. Many Samsung smartphones are unremarkable, but Samsung has turned its high-end Galaxy S and larger-sized Galaxy Note into household-name franchises that together accounted for more than 100 million shipments in 2013.

Flooding the market isn’t a winning strategy by itself. What sets Samsung apart is its more integrated approach toward production. In smartphone manufacturing, integration is a major advantage, because it allows companies to move quickly and wield more control over phone appearance and performance. Apple is able to integrate its hardware and software because it designs the iPhone, its operating system, its core services, and some of the phone’s most important components, such as the iPhone’s processor. Samsung is able to integrate its phone hardware down to the component level because it makes many of its phones’ parts, including screens, processors, and memory chips. These particular components attract high consumer interest and are some of the most expensive parts, which has been a boon to Samsung.

Most smartphone makers outsource the creation of their components and operating systems to other companies. Apple and Samsung’s synergies enable them to be first to market with the most cutting-edge smartphones. Being first is important, because carriers and retailers are always looking for new phones to promote and consumers are always looking for innovative phones to buy. In this hypercompetitive industry, speed and control translate into sales and profits.

Tight integration and comprehensiveness aren’t Samsung’s only weapons: it also uses marketing to outflank its competitors. In 2012, Samsung spent more on global marketing ($11.6 billion) than on R&D ($10.3 billion). More than $400 million of that money went to the United States for ads that feature its phones. Apple spent 17 percent less ($333 million) on U.S. ads for the iPhone that year. In 2013, Apple increased its spending 5 percent to about $351 million, and Samsung reduced its by 10 percent, but still spent more—about $363 million.21 In 2014, Samsung paid an estimated $18 million to run commercials during that year’s Academy Awards broadcast—a deal that resulted in host Ellen DeGeneres using a Galaxy Note 3 to organize a star-studded “selfie” photo that, when pushed to Twitter, became the most retweeted tweet ever.22 Reuters has called the company “the world’s biggest advertiser.”23

Samsung also invests in co-marketing, which are payments phone makers make to carriers and other retailers to promote their phones. (In contrast, Apple expects carriers to devote much of their marketing budgets to iPhone ads to meet the sales obligations in their iPhone contracts.)24 Carriers use co-marketing funds to run TV, online, outdoor, and in-store ads about devices and to offer special promotions. For example, when a carrier gives consumers a free Samsung phone with the purchase of another Samsung smartphone, and heavily advertises the offer, Samsung is probably paying some portion of those expenses. Smartphone makers say Samsung gives carriers more co-marketing money than other companies do, which makes sense given its size and profitability. The more money Samsung gives carriers, the more ads and promotions they run featuring Samsung phones.

Samsung’s next target is the big smartphone ecosystems. As a phone maker, Samsung doesn’t need to establish an app ecosystem; it already participates in those of Android and Windows Phone through its devices. But having its own ecosystem would give Samsung more control over its products and yield more profit. As Dediu has written, “Samsung must either stretch into becoming one of the ecosystem contenders or be relegated to a commodity hardware company.”25

Samsung has been trying to build an ecosystem since 2009, first by introducing its own smartphone operating system bada, which it used outside the United States and has since retired, and now by backing the open-source, Linux-based Tizen, which also has support from the chip maker Intel and six Asian and European carriers. In March 2013, Aapo Markkanen, a senior analyst for the market research firm ABI Research, wrote, “All signs are pointing to Samsung trying to pull off a Great OS Escape [from Android to Tizen] within the next year or two.”26 Samsung prepared for this escape by creating its own Android-based apps that duplicated some of the functionality of Google’s. Samsung also spent freely to shore up its weakness in software. Internally, Samsung directed half of the employees in its research and development division to work exclusively on software projects. Externally, Samsung hosted its first-ever developer conference in San Francisco in October 2013, followed by a gathering for European developers in London. The goal: to recruit developers to make apps specifically for its devices, first on Android and later on Tizen. Samsung also went on a Silicon Valley hiring and construction spree. In less than a year it established a start-up accelerator and a strategy and innovation center and broke ground on a new campus for R&D and sales staff.

The moves raised Samsung’s profile among American start-ups, software firms, and developers, but in January 2014 Google brought Samsung back into the Android fold by selling Motorola to China’s Lenovo and signing a 10-year patent cross-licensing agreement that lets Google and Samsung use technologies covered by the others’ patents. Since Samsung and other Android device makers regarded Google as a competitor after it acquired Motorola and began producing smartphones, shedding Motorola improved Samsung-Google relations. At the same time, Google saw a benefit in combining Lenovo and Motorola, because they would create a strong number-two Android phone vendor that could keep Samsung in check. Vakulenko says Android’s success depends on having a “balance of power” among its phone makers, and Google sold Motorola to restore that balance.

While Samsung hasn’t made its Great OS Escape yet, it doesn’t appear to have scrapped the idea, either. It continues to develop Tizen and is using it as the operating system for its Gear 2 smartwatches, which wirelessly connect to its Galaxy smartphones. Samsung executives have said that Android “still needs to be our main business,” but that Tizen will be an important secondary platform for the company.27

Samsung’s rise has already touched off a war with Apple. Samsung used to produce several iPhone parts, including the processor and screen; the very first iPhone contained a Samsung processor and memory chip. But when Samsung started challenging Apple’s smartphone sales, Apple dropped it as a key iPhone supplier. In 2010, Apple hired Sharp and Toshiba to make iPhone screens.* In 2013, the Wall Street Journal reported that Apple had tapped Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) to make iPhone processors.28 Apple’s new suppliers are leaders in their fields, but analysts say Apple primarily switched to slash Samsung’s profits and keep its iPhone technology plans and business forecasts confidential from its fiercest competitor. According to the Wall Street Journal, TSMC took several years to produce chips that met Apple’s high standards, while Sharp and Toshiba had to expand their factories just for Apple.29 In contrast, Samsung had already mastered these processes.

Samsung is anticipated to lose at least $10 billion in annual revenues if Apple fully backs away. That could happen in 2015, although some experts, including the Korea Times’s Kim Yoo-chul, don’t believe Apple will completely drop it. Kim notes that Samsung is known to guarantee on-time delivery, high levels of production, and competitive pricing to its customers, which makes it an attractive manufacturing partner. “Although it’s true that Apple is cutting its reliance on Samsung, that doesn’t mean Samsung will be excluded from the development of A-series [iPhone processor] chips,” contends Kim. “Apple is ordering some chips from TSMC as part of its strategy to diversify its sourcing, but Samsung will remain a top-tier Apple supplier.” Recent media reports in Korea and Taiwan30 indicate Samsung may retain 30 percent to 40 percent of Apple’s chip business.

PATENT WARS

Patents are another battleground in the smartphone wars. The current spate of lawsuits kicked off in 2009 when Nokia sued Apple for allegedly violating its wireless technology patents. Since then, every major smartphone maker and platform provider has sued or been sued by at least one competitor. This not so exclusive group includes Apple, BlackBerry, Google, HTC, LG, Microsoft, Motorola, Nokia, Samsung, and Sony. Of them, Apple and Microsoft have been the most proactive about protecting their intellectual property (IP) rights—or, from some people’s perspective, the most ruthless in attacking their rivals.

Smartphone patent lawsuits generally allege infringement of technical inventions or designs or both, and the plaintiffs aim to block competitors’ sales, force them to alter their phone designs or technology, or elicit large lump sums or ongoing fees. Since patents can be brandished both offensively (to sue another company) and defensively (to ward off lawsuits), the patent fights have fueled billions of dollars of patent purchases. David E. Martin, the chairman of intellectual property management firm M-CAM, describes this frenzied accumulation of patents as “the aggregation of warheads to use for litigation.”

In 2010, Apple and Microsoft teamed up with a few other tech companies to buy 882 patents mostly related to open-source software for $450 million from the computer software firm Novell. (Citing antitrust concerns, the U.S. Department of Justice later ordered Microsoft to sell back its share of the Novell patents and license them instead.) The following year, a team that included Apple, BlackBerry, Microsoft, and Sony won the biggest-ever auction of technology patents by spending $4.5 billion to buy 6,000 patents and patent applications from Nortel, a bankrupt telecom equipment provider. Nortel’s patent portfolio covered the full breadth of telecommunications, including voice communications, data networking, semiconductors, and—most valuable of all to smartphone companies—wireless technologies, including high-speed 4G LTE. Google also bid for the Nortel patents, but it lost. To compensate, Google purchased 2,000 cellular, online search, and wireless technology patents from IBM for an undisclosed sum and spent $12.5 billion to buy Motorola, its largest-ever acquisition.

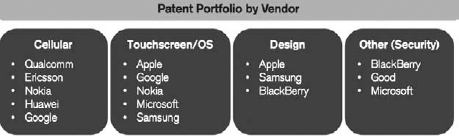

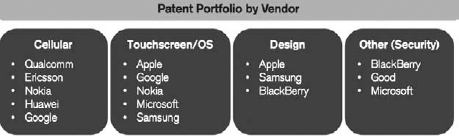

The main types of smartphone patents and the companies that hold them (Kulbinder Garcha/Credit Suisse)

Due to their pricy Nortel and Motorola purchases, Apple and Google spent more on patents than on research and development in 2011. Google has said Motorola’s more than 17,000 patents are worth $5.5 billion, but during the years Google owned Motorola, it was not able to assert them against its competitors in a significant way.* Martin says that what Google really bought was “annoyance value.” “The number of patents is valuable even if the patents themselves are worthless, because [opposing] lawyers then have to read a lot of patents,” he explains.

Much of the public attention on smartphone patent fights has focused on these billion-dollar purchases, new lawsuit filings, outsize jury verdicts, and companies’ attempts to crimp each other’s sales and imports through injunctions. However, Florian Mueller, a noted IP analyst who writes the popular blog FOSS Patents and consults on wireless devices for companies, including Microsoft, says the battle is more complex than the typical winner-take-all narrative. “This is a much more sophisticated game than a boxing match where you go into the ring for twelve rounds—or less, in the event of a K.O.—and have a result after about an hour,” says Mueller. And landing a quick knockout is tough in smartphone patent fights, which often pit deep-pocketed giants against other deep-pocketed giants. Says Mueller, “The U.S. legal system is simply very slow if there’s a well-funded, sophisticated defendant prepared to exhaust all procedural options and to stall.”

Consider the multiyear, ongoing feud between Apple and Samsung. Apple started the skirmish in April 2011 with a 373-page complaint that alleged Samsung had knocked off its iPhone and iPad software features and designs, that it needed to halt its infringing behavior, and that it owed Apple monetary damages. According to Apple’s filing:

Instead of pursuing independent product development, Samsung has chosen to slavishly copy Apple’s innovative technology, distinctive user interfaces, and elegant and distinctive product and packaging design, in violation of Apple’s valuable intellectual property rights. . . . Samsung has made its Galaxy phones and computer tablet work and look like Apple’s products through widespread patent and trade dress infringement. Samsung has even misappropriated Apple’s distinctive product packaging. . . . Apple seeks to put a stop to Samsung’s illegal conduct and obtain compensation for the violations that have occurred thus far.31

The two companies have since sued and countersued each other in ten countries across Asia, Australia, Europe, and North America in what Apple referred to as “a worldwide constellation of litigation”32 in its filings. Both companies have offered to license their patents to the other, but each rejected the proposed rate as too high. Apple also wanted any proposal to include an “anti-cloning” provision that would let it sue Samsung in the future for products it deemed overly similar to its own, according to Mueller.

The most notable Apple-Samsung fight took place in a U.S. district court in San Jose, California. In August 2012, following a widely chronicled four-week trial that the Wall Street Journal dubbed THE PATENT TRIAL OF THE CENTURY,33 a San Jose jury decided Samsung had infringed six Apple patents—three utility (technical) ones and three of design—and owed Apple $1.05 billion in damages. The utility patents covered: so-called rubber band technology, which gives a bounce-back effect when smartphone users scroll beyond the top or bottom edge of a page; “pinch to zoom” multitouch technology, which can distinguish between a vertical/horizontal finger movement and a diagonal movement,34 enabling recognition of pinch and reverse pinch movements; and “tap to zoom and navigate” technology, which refers to users navigating to another part of the phone screen after they tap their phone screen twice to minimize or enlarge text and images. The design patents covered the iPhone’s appearance, including the distinctive metal rim that surrounds its glass display and the grid of round-cornered icons on its home screen. The more than 20 implicated Samsung phones included the original Galaxy S and SII, as well as other Android phones released in 2010 and 2011.

Six months later, citing jury errors, the judge vacated the damage fees associated with 14 of the Samsung products (later amended to 13) and scheduled another trial to recalculate them. The decision from that trial, which took place in November 2013, set the amount Samsung owed Apple at $290 million, which changed the total amount of payable damages to about $930 million. Since the revised award was about 90 percent of the amount initially determined by the 2012 jury, it was interpreted as a disappointment for Samsung. As Mueller wrote, “Samsung had challenged last year’s jury award but obviously intended to get more out of a retrial than a 10 percent discount.”35

In 2014, Apple and Samsung faced off again in the same court over a different set of utility patents* and mostly newer devices, including the Galaxy SIII, the Galaxy Note and Note II, and the iPhone 4, 4.5, and 5. Apple originally sought $2.2 billion in damages while Samsung asked for $6.2 million. The jury delivered a mixed verdict, ruling that Samsung should pay $119.6 million for infringing three of Apple’s five patent claims-in-suit and Apple should pay Samsung $158,400 for infringing one of Samsung’s two patent claims-in-suit.

The Apple-Samsung patent battle isn’t over yet. Samsung has appealed the 2012 verdict and Apple has filed a cross-appeal. Samsung has also said it plans to appeal the 2014 verdict. Smartphone patent fights can spend years winding through appeals courts. “With a very few and negligible exceptions, each and every decision by a first-instance court in these [smartphone patent] disputes has been appealed, and most of these appeals haven’t been resolved yet,” says Mueller. “Or if they have been resolved, the cases themselves are still ongoing, because the appeals court remanded them . . . for further proceedings.” With billions at stake, neither Apple nor Samsung will capitulate easily.

Many experts view the Apple-Samsung war as an attempt to hold back the competitor. “Apple and Samsung are interested in interrupting each other’s ease of market access, not in defending their patents,” says Martin. “From their perspective, the more they can interrupt each other, the better.” The suits can also be seen as a proxy for Apple and Google’s long-simmering animosity. All the Samsung devices implicated in the Apple-Samsung suits run on Android. Apple has said Android “provides much of the accused functionality”36 at issue in its Samsung suits. Steve Jobs famously called Android a “stolen product” and vowed to “destroy” it.37

However, experts such as Mueller also contend that it would be financially irresponsible for Apple to ignore allegedly infringing behavior. Since Apple’s design and brand enable it to command huge price premiums, it must “defend its uniqueness” in order to protect its core business, Mueller says. “Non-enforcement is not an option for major right holders that own valuable IP” such as Apple and Microsoft, he adds.

These companies target Android device makers instead of Google because of Android’s dispersed business structure. “[As a plaintiff] you don’t start an outright war with [an] entire ecosystem; you focus on one particular infringer,” points out Mueller. Arguing that Samsung sold infringing devices worth $3.5 billion, as Apple did in its 2013 retrial, is “a much better story” to present to a jury, he adds, than arguing that Google benefited indirectly, through advertising revenues, from patent-infringing Android devices it did not make.

Even though Google is generally not named in its Android device makers’ lawsuits, it helps its partners defend themselves, to some extent. In 2011, Google transferred nine of its user interface and wireless communications patents to HTC so HTC could assert them against Apple, which it was battling at the time over an array of user interface and technical patents. Google has participated in a few Android lawsuits as an intervenor—a third party added to ongoing litigation—though it appears to intervene only when its smaller partners, such as HTC, are involved. In those cases, Google supported its partners by defending the Android-specific parts of the lawsuits. It also makes available lawyers from Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan, its go-to law firm for patent and copyright cases. Quinn Emanuel lawyers have appeared in court on behalf of HTC (in an earlier skirmish with Apple) and Samsung (in its various Apple trials). These arrangements appear to stem from indemnification agreements between Google and Android device makers. A 2013 CNET article summed up Google’s assistance to Samsung as: “quietly lending support, coordinating with Samsung over legal strategies, providing advice, doing extra legwork, and searching for prior evidence.”38 Deposition testimony from the 2014 Apple-Samsung trial further revealed that Google also offered to handle its partners’ litigation and defense and to pay at least some legal costs and potential damages for patents that involve core Android features.

Google was a more active combatant through Motorola, which has tried to stymie Apple with patent claims. In 2012, Motorola (which by then was part of Google) sued Apple over seven patents related to its Siri voice-activated personal assistant and other iPhone features. Motorola later dropped the suit. Google also inherited an ongoing Motorola-Apple infringement dispute that began in 2010, which now involves eight wireless communication and smartphone patents.

Much of Microsoft’s smartphone patent activity is aimed at Android manufacturers. Claiming Android built on top of its computer operating-system and web browser software inventions, Microsoft has convinced more than 20 device makers, including HTC, LG, and Samsung, to pay licensing fees to it. “Microsoft’s model has been less court action, more a quiet word in the ear,” observed the Register, a British technology news site.39 Microsoft has said the agreements cover 80 percent of Android phones sold in the United States and the majority of Android phones sold worldwide. The fees are believed to run $5 to $10 per handset and are estimated to net Microsoft $1.6 billion a year, according to global investment bank Nomura Securities.40 If the estimate is correct, Microsoft’s Android licensing business was more than four times more profitable than its Windows Phone licensing business was during Microsoft’s fiscal year 2013—and thus may have helped Microsoft decide to make Windows Phone free in 2014.

Microsoft and its supporters say it is simply asserting its intellectual property rights, but Android royalties are also a way for it to obstruct Google without suing it directly. Attaching a cost to using Android reduces the software’s allure to phone makers while making Windows Phone more appealing. In 2011, Google publicly expressed its ire over this “tax for . . . dubious patents.”41 The outburst didn’t daunt Microsoft, which continues to strike Android licensing deals.

Besides tying up courts around the world, smartphone patent disputes have also ratcheted up activity at the U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC). Apple, Microsoft, Motorola, Nokia, and Samsung have all taken cases to the ITC in recent years. Companies petition the ITC because it acts quickly and has the power to bar imports of patent-infringing products. For cash-rich companies such as Apple and Samsung, injunctions (and subsequent design changes) are the real goal, not onetime damages payouts. Since most U.S. smartphones are assembled in China and must be imported, an ITC injunction could maim any smartphone company with a sizable U.S. business. Freezing a company’s shipments at the border would allow its competitors to surge ahead, at least until the company devised non-infringing modifications known as workarounds.

ITC orders aren’t always enforced or upheld, however, and presidential administrations can veto ITC bans. For decades no president exercised that power, but in 2013 the Obama administration, acting through the U.S. trade representative (USTR), overturned an ITC ban Samsung had won that affected older Apple products, such as the iPhone 3GS and 4.

Google’s latest problem is a small, Ottawa-based company. Rockstar describes itself as an IP licensing company, but reporters and people in the technology industry call it a nonpracticing entity (NPE) or a patent-assertion entity (PAE). NPEs, often derided as “patent trolls,” primarily buy patents for litigation and licensing purposes rather than to produce a product or service. In 2013, Rockstar simultaneously filed lawsuits against eight Android companies, including Google, HTC, LG, and Samsung. The Google suit alleged infringement of seven search advertising patents, while the other suits alleged all the manufacturers’ Android devices infringed seven (and in some cases just six) patents related to mobile messaging, user interface design, and data networking. Rockstar later added Google as a co-defendant to its Samsung/Android suit. Most of the Android manufacturers have filed motions to dismiss Rockstar’s suits.

NPEs are, by nature, opportunistic in their business dealings, but Rockstar aggravates Google and Samsung more than other NPEs, because it has links to Apple, BlackBerry, and Microsoft. After the Nortel auction, Apple, BlackBerry, Microsoft, Sony, and other partners divvied up about 2,000 of the 6,000 Nortel patents and established Rockstar as a company to make money off those remaining. Although Rockstar is independent from Apple, BlackBerry, and Microsoft, and its CEO insists it selects its targets itself, the company has a direct and financial connection to Android’s biggest rivals. The tech news site Ars Technica called the Rockstar suits “an all-out patent attack on Google and Android” that drew upon “the patent equivalent of a nuclear stockpile.”42

Since most companies would rather avoid the distraction and expense of going to trial, NPEs are able to extract payments and licensing agreements from at least some of the companies they threaten. NTP, a Virginia-based patent holding company, is the smartphone industry’s most notorious example of NPE success. In 2006, RIM (BlackBerry), which was facing an injunction that would have seriously harmed its smartphone business, paid NTP $612.5 million to resolve a five-year dispute over wireless e-mail patents. Emboldened by its victory, NTP asserted its wireless e-mail patents in suits against other major smartphone companies, including carriers (AT&T, Sprint, T-Mobile, and Verizon Wireless), phone makers (Apple, HTC, LG, Motorola, Samsung), and platform providers (Google and Microsoft). In 2012, NTP reconciled with all of these companies for undisclosed terms.

The Obama administration tried to mitigate patent trolling with the America Invents Act, which was signed in 2011. Though it was billed as landmark legislation, the patent reform law primarily made administrative changes, such as updating patent-filing procedures, and experts say patents remain overly broad and easy to abuse. Congress is also trying to stamp out trolling with the Innovation Act, which is specifically designed to amend and improve the America Invents Act. The act includes patent reform provisions, such as requiring patent complaints to include more details about the alleged infringement and helping defendants recoup their legal fees if they prevail against a troll in court. The U.S. House of Representatives passed the bill in December 2013.

The Innovation Act won’t fix one of the American patent system’s chief flaws: the surplus of shoddy patents, especially software patents. (Recent attempts by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office to improve technical training for its patent examiners and judges could help, however.) “There are too many patents being issued on stuff that isn’t a true invention,” says Martin. “Getting a patent [these days] is just evidence you argued with a patent examiner until he got tired and gave you a patent.” By M-CAM’s count there are about 210,000 cell phone patents in the world, approximately 180,000 of which relate to smartphones.43 As of the end of 2013, Apple held 852 smartphone-related patents and Samsung had 1,964. “In a world of 200,000 mobile phone patents, what’s innovation?” asks Martin. “The universe is so cluttered with patents, no one really knows what they have.”

Carriers don’t generate headlines the way Apple, Google, and Samsung do. Nevertheless, the smartphone-related carrier wars should not be overlooked. Carriers fight with each other over lucrative smartphone consumers, and they fight with smartphone platform providers over industry revenues and control. U.S. carriers have their own duopoly—AT&T and Verizon Wireless, which control about two thirds of the U.S. wireless market. The number three and four largest U.S. carriers—Sprint and T-Mobile US—are employing increasingly combative and creative tactics to steal market share from the two leaders. These carrier-initiated battles shape the smartphone industry, too.

The intracarrier battles are familiar to most consumers because the tussles are highly public and are often provoked and propelled by marketing claims. Carriers pour billions of dollars into ads that attack their rivals and try to persuade consumers to switch service providers. According to Advertising Age, AT&T spent $2.91 billion on marketing in 2012, and Verizon was right behind AT&T with $2.38 billion.44

One of the most famous carrier attack ads was Verizon’s 2009 “There’s a Map for That” campaign against AT&T, which contrasted U.S. maps showing Verizon’s nationwide 3G network coverage with ones depicting that of AT&T. Unsurprisingly, the maps made Verizon’s network look far superior. AT&T sued Verizon for “misleading” consumers, which it said was causing it to lose “incalculable market share,”45 and it ran retaliatory ads in an attempt to refute Verizon’s allegations. By the time AT&T dropped the suit a month later, the clash had attracted mass attention. Advertising Age called it “a big-bucks marketing battle that’s already threatening to make the cola wars [between Coke and Pepsi] look like child’s play.”46

In 2013, Verizon renewed its map marketing attack with a series of commercials that used visual comparisons of maps—hung in a gallery like abstract art, in one ad—to show Verizon covered more of the country with 4G LTE than AT&T, Sprint, or T-Mobile. But these days the fiercest advertising war is between AT&T and T-Mobile. Recently appointed T-Mobile CEO John Legere touched off the quarrel in early 2013 when he called AT&T’s network “crap” at the Consumer Electronics Show (CES), the world’s largest consumer technology trade show.47 AT&T and T-Mobile have traded insults ever since, in both newspaper and TV ads. AT&T has said T-Mobile has twice the number of dropped calls and half the download speed as its own network. T-Mobile has accused AT&T of deliberately confusing and overcharging its customers, and Legere regularly slams AT&T on his Twitter account; he even crashed AT&T’s 2014 CES party (only to be escorted out by security). In 2014, both carriers offered to pay the other’s subscribers hundreds of dollars to switch to their networks. (T-Mobile’s “break up with your carrier” campaign also extended to Sprint and Verizon customers. Sprint later launched a similar promotion.) Analysts say T-Mobile’s aggressive marketing is helping it gain subscribers, so the carrier will probably continue hurling insults for a while.

Carrier animosity toward Apple and Google is subtler—more a case of simmering tension than in-your-face smack talk. Carriers resent the way platform providers usurped their power over smartphone subscribers and their revenues from mobile content sales. Before the iPhone launched, carriers controlled the smartphone ecosystem. Everything a user did, whether it was talking, texting, or accessing the Internet, took place on the carrier’s network, and the carrier got paid for it. Carriers also operated online portals, where they sold mobile content such as ringtones and games, steering their subscribers to these portals and pocketing most of the profit from content sales. Analysts often described this setup as a walled garden, similar to Apple’s App Store, but with carriers as the gatekeepers.

The iPhone set off a chain of events that shifted the smartphone industry’s balance of power. As the mobile industry transitioned from mobile telephony to mobile computing, platform providers and smartphone makers pushed carriers to the sidelines. Apple first loosened the bonds between carriers and subscribers. Before the iPhone, smartphone makers didn’t have close ties with their users; they let carriers fill that role. Apple co-opted the carriers’ customer relationships by selling the iPhone directly to consumers and designing it to be activated, registered, and updated through iTunes. iPhone owners started looking to Apple for information about their phones.

Apple also poached the carriers’ mobile content business by opening the App Store. Money from apps and mobile media that used to flow to the carriers through their online portals now goes to Apple, Google, Microsoft, and their platform-specific app stores. Google mollifies carriers by giving them part of the 30 percent cut it gets on app sales. “Google paid operators [carriers] because it wanted to flood the market with Android devices,” says Vakulenko. “It needed to attract operators’ support and make sure they were putting marketing into promoting Android.” But now that Android is a runaway hit, Google appears to have changed its policy. It is reportedly trying to renegotiate its carrier agreements to give itself a bigger percentage of app revenues.48

These developments threaten to make carriers into generic providers of utility services. In industry lingo, the phrases are “dumb pipes” or “bit pipes,” as in the data bits and bytes carriers transfer between their subscribers’ mobile devices and the Internet. If carriers become mere data pipes—and some industry observers say they already are—carriers will have to compete largely on price, which will reduce their profits.

To minimize their dependence on Apple and Google, carriers are backing a range of new smartphone platforms. “There’s an appetite in the industry to move away from the Android-iOS duopoly and really look at alternative operating systems,” says Michael O’Hara, the chief marketing officer of the GSM Association (GSMA), which grew out of the coalition of European carriers that agreed to deploy GSM back in 1987, and is now the world’s largest industry group of mobile-related companies. The new platforms come from either start-ups or established software providers that are expanding to smartphones. Most of them are licensing their software to multiple smartphone makers rather than making their own phones, which means they are more of a challenge to Android than iOS. Firefox OS is currently the most popular of these Android alternatives. Mozilla, the California company that makes the Firefox Web browser, commercially released Firefox OS in 2013. Some of the world’s biggest carriers, including Spain-based Telefónica, are selling Firefox OS smartphones, and Sprint has expressed interest in eventually carrying them. Some large carriers are backing Tizen, as well. NTT DOCOMO, France’s Orange, Korea’s SK Telecom, and London-based Vodafone, the world’s number-two carrier, are all members of the Tizen Association.

Windows Phone also has benefited from carriers’ mistrust of Apple and Google. In 2013, Telefónica agreed to promote Windows Phone 8 smartphones across Europe and Latin America, stating that it wanted to “encourage the presence of additional mobile operating systems as an alternative to Android and iOS.”49

SOFTWARE WARS

Smartphone software is more than just operating systems. Apps are key to the smartphone experience, and most operating system providers make at least some of their apps available on competing platforms. BlackBerry translated its BlackBerry Messenger (BBM) software for Android and iOS, and is doing so for Windows Phone. Google issues iOS variations of its main apps, such as Google Search, Gmail, Google+, and Google Drive, its service that stores and synchronizes files on remote servers in the cloud and enables access to them via the Internet.

Microsoft produces multiple mobile versions of Bing, its search engine; Office; and OneDrive, its online file storage service. Apple is the lone holdout. Apple reserves its software innovations for its own customers. If you want to video chat on FaceTime or talk to Siri, you must do so on an iPhone, iPad, an iPod, or a Mac.

Google is more open than Apple, but only to a certain extent. Its Maps and YouTube apps have provoked fierce skirmishes between smartphone companies. The clash between Apple and Google was the most public. In 2012, Apple dropped Google Maps and YouTube from the iPhone due to competitive concerns. Both apps had been mainstays on the iPhone home screen since 2007, but Apple debuted its own map and video software on the iPhone 5. Industry insiders interpreted the move as Apple’s plan to create a “Google-free iPhone.”50 Not only was Google getting invaluable cachet from being the iPhone’s default mapping and video-playing service, it was also collecting a huge amount of data from iPhone users’ map and video searches. Google mined that information to improve its products and learn more about people’s mobile habits.

Google was also using Maps as a weapon. Starting in 2009, Google steadily augmented the Android version of Google Maps with features such as voice-guided turn-by-turn navigation and fast-loading vector maps that could be saved offline. Google refused to license these addons to Apple, viewing them as a competitive advantage for Android. Apple’s anger at being limited to an inferior version of Google Maps was one reason it removed the app from the iPhone.

Apple Maps was deeply flawed, and consumers lambasted Apple as soon as they realized its replacement technology was incomplete and unstable. Some Apple Maps directions suggested roundabout routes, Manhattan’s bustling Lexington Avenue appeared in the neighboring borough of Brooklyn, and the Huey P. Long Bridge, which spans the Mississippi River, was located on dry land inside the city of New Orleans—to name a few examples. The maps also failed to locate major landmarks, such as Dulles International Airport, one of the Washington, D.C., area’s main airports. While many of the errors were mildly annoying, some were dangerous, such as directions that instructed users to drive on train tracks and stranded people in the Australian desert.

The iPhone 5 still set a new opening-weekend sales record for Apple of more than 5 million units, but the public outcry eventually grew so loud that CEO Cook issued an apology. When Google released a downloadable, stand-alone Google Maps app about three months later, ravenous Apple users downloaded it more than 10 million times within two days. Google continues to distribute Google Maps and YouTube through the App Store as stand-alone apps.

In what has been dubbed “mapageddon,” Apple and Google still compete fiercely over mapping technology, buying at least six mapping start-ups (total) in 2013 to bolster their technology arsenals. Both are motivated by the revenue potential of serving local ads to smartphone users who conduct searches via mapping apps. While the mobile maps–based ad market is small now—about 25 percent of all mobile ads, according to one estimate—it will certainly grow. As the Washington Post has noted, “Just as the algorithm for finding information on the Web became the key to Google’s search dominance, the precision and functionality of maps will be the key to mobile dominance.”51

Google and Microsoft also fight over software. Their disputes have been less conspicuous but more hostile. Their most serious feud is over YouTube, since Google refuses to build a YouTube app for Windows Phones the way it does for iPhones. In 2011, Microsoft cited the situation as evidence of Google’s anticompetitive behavior in a complaint to the European Commission, which at the time was investigating whether Google had violated European competition law in the search and advertising markets. Microsoft also raised the issue with the U.S. Federal Trade Commission. In 2013, when Microsoft created its own Windows Phone YouTube app, Google demanded Microsoft pull it, because it didn’t comply with YouTube’s terms of service. The skirmish attracted media attention, and the two companies appeared to compromise, publicly stating that they would work together to build a new Windows Phone YouTube app.

The brawl re-ignited several months later. In August 2013, Microsoft published a blog post entitled THE LIMITS OF GOOGLE’S OPENNESS, claiming that it had amended its YouTube app but that Google used software to block it upon release.52 The Microsoft lawyer who wrote the post implied that Google was discriminating against Windows Phone because it uses Bing as its default instead of Google. In response, Google said it blocked the app because it continued to violate YouTube’s terms of service. The Verge concluded, “Both companies are acting like children, and while the fight drags on, customers lose out.”53

Microsoft appeared to capitulate in October 2013 by releasing an app that redirects users to YouTube’s regular mobile website. As CNET wrote, the new app “jettisoned all of the extra features in prior versions . . . essentially negating the whole purpose of using a dedicated app in the first place.”54 In other words, the app wasn’t really an app.

What’s really behind the Google-Microsoft YouTube squabble? Google has said Windows Phone doesn’t have enough users to warrant the resources Google would need to invest in developing apps. That argument is valid, but Microsoft is shouldering the bulk of the work and expense of the Windows Phone YouTube app, not Google. And Google does have at least one Windows Phone app: a version of its Google Search app. Perhaps Google simply wants to weaken Windows Phone by withholding one of its most popular apps.

DEVELOPER WARS

As platform providers vie to have the greatest number of app downloads, third party apps and the developers that make them have become so central to the smartphone business that companies spar over them, too. Apple is ahead at the moment, with more than 70 billion apps cumulatively downloaded since 2008, compared to more than 50 billion for Google. But due to its larger number of users, Google Play notched more than 15 percent more annual (not cumulative) downloads than the App Store in 2013, according to the mobile app analytics firm App Annie, and it is projected to pass the App Store in total app downloads soon.

Platform providers also compete over their total number of apps, which is one of the most closely watched and oft-cited metrics of a smartphone ecosystem’s size and vitality. Google is currently winning this contest, stocking more than 1 million Android apps in Google Play as of July 2013. Apple hit the 1 million mark in October 2013. Microsoft and BlackBerry have far fewer: 245,000 and 140,000, respectively.

To narrow this gap, BlackBerry and Microsoft pay developers to build apps for their platforms. Vakulenko disapproves of the strategy, noting, “You can’t buy developer love.” Developers, he says, will take the money and churn out a so-so app. But BlackBerry and Microsoft have little choice; they need to give developers a reason to work with them. In the months leading up to its 2013 launch of BlackBerry 10 BlackBerry paid small developers $100 for every compatible app they wrote. The company ended up with 40,000 new apps. It also offered up to $9,000 for more sophisticated BlackBerry 10 apps. Microsoft reportedly pays well-known developers, such as the location-based social networking service Foursquare, $60,000 to $600,000 to make Windows Phone apps.55 Microsoft has also created apps for more than 90 popular companies by taking their mobile websites, repackaging them, and stocking them in its Windows Phone store. This initiative attracted controversy, since the companies, such as the ticket seller Ticketmaster and the hardware store Lowe’s, didn’t approve or even know about the apps.56

Apple and Google are in a different position. Rather than invest large sums of money in breaking through to developers, they just need to maintain their leadership as app ecosystems. Both offer developers marketing and promotional assistance to convince them to exclusively launch their apps in their stores. Apple also attracts developers by highlighting its status as the most profitable app store. All major app stores, including those run by Apple, Google, and Microsoft, take 30 percent of an app’s sale price as a processing fee and give the remaining 70 percent to the developer. Apple regularly brags about the amount of money it has cumulatively paid out to its developers—$15 billion as of January 2014.

Google also publicizes Google Play’s revenue growth, but in more abstract terms. For example, in April 2014, Google said it disbursed more than four times as much money to Android developers in 2013 than it had in 2012. It is difficult to estimate how much money that is, since Google doesn’t specify how much its developers have earned in dollars. Google’s reticence may be due to the fact that the amount is likely far lower than Apple’s. The App Store makes more than twice the app revenue of Google Play, according to App Annie.57

Some of the most intense smartphone wars happen within app stores. Developers wage their own wars with each other. Smartphone ecosystems take care of one major developer worry: access to consumers. But stocking an app in a huge app store doesn’t guarantee sales. Making a hit app is getting harder, due to a problem the industry calls “discoverability.” In any app store a small group of apps, including the hottest games of the moment and the perennially popular, well-known services such Facebook and Pandora Radio, claim the lion’s share of users’ time and/or money. Developers outside this group must fight for scraps.

Developers are also having more trouble charging for their apps, due to the glut in the market, especially of free apps, which comprise more than 90 percent of all those downloaded. Developers give away their apps in hopes of making money through in-app purchases of virtual goods, game levels, and other extras or by convincing people to trade up to a paid, ad-free version. The trouble with these so-called freemium apps is that most consumers are content to stick with the free version.

App developers are a diverse crowd, from publicly traded companies such as Electronic Arts to precocious kids. The market analysis firm VisionMobile divides developers into eight groups: hobbyists are people who want to learn app development and have fun; explorers often work in the mobile or technology industry and are looking to make extra income on their own; hunters are professional developers who own or lead app development companies and seek to bring in as much money as possible with hit apps; guns for hire are professional developers aiming to attract commissioned or contract app work from other companies; gold seekers are start-ups focused on amassing a large audience for a free app as quickly as possible, in order to raise venture capital funding; product extenders are consumer goods companies that use apps to attract consumers to their main products; digital media publishers are magazines and news organizations that release their content through apps to lure readers; and enterprise ITs are large companies that create apps for internal employee usage. Of the eight groups, only hunters and guns for hire aggressively seek direct revenues from their apps.

Some hunter companies have minted hundreds of millions of dollars from their apps. The most notable are King, the Dublin-based producer of the candy icon-matching game Candy Crush Saga (though its 2014 initial public offering underperformed expectations); Finnish start-up Supercell, which makes the combat strategy game Clash of Clans and is valued at roughly $3 billion; and game publisher Rovio, creator of the blockbuster Angry Birds bird-and-pig–themed slingshot game. These success stories obscure the fact that 60 percent of the small, independent developers who want to make money off their apps earn less than $500 a month, according to VisionMobile.58 Creating an app costs more than $27,000, on average, for iOS and more than $22,000 for Android,59 due to the expense of paying developers and designers and purchasing tools, including computers, smartphones, and software. Struggling developers would need between four and five years just to recoup their costs.

Since consumers rely on short lists, for instance the top free apps and top paid apps in the App Store or Google Play, to filter good apps from bad, inclusion on these lists can increase downloads by many multiples. The App Store bases its “top apps” rankings primarily on an app’s download volume and velocity (meaning the number of downloads in a given time period). Google Play weighs several factors, including app ratings (from user reviews) and an app’s ability to attract and retain active users. Craig Palli, the chief strategy officer at Fiksu, a mobile app marketing firm that tracks app store trends, says the differences reflect the companies’ backgrounds and strengths: Apple’s as a seller of music, which traditionally gets ranked by popularity, and Google’s as a search company that uses complex algorithms to rank results. The Windows Phone Store takes a hybrid approach, spotlighting highly rated apps alongside more conventional rankings.

The hurdle for new and obscure apps is getting onto the lists in the first place. Since 2009, more than 500 companies have released various app-related tools to assist bewildered developers, and this booming “SDK economy”60 provides many ways to strategize an app’s release, through ads, social media, and promotions.

To spur sales, a number of developers are buying so-called mobile app install ads that encourage consumers to download apps by providing direct links to app stores. Facebook pioneered these ads in its mobile app in 2012 and Yahoo, Twitter, and Google have created their own versions. Ads alone can’t propel an app to the front of the App Store, though, so some developers break App Store rules by paying sketchy “app promotion” companies thousands of dollars to get their apps there. Silicon Valley’s GTekna says it was the first app promoter to guarantee developers App Store placement. Starting in 2009, the company charged developers $7,000 to $15,000 to push an app into the App Store’s top 25 over the course of two to three days. An app needed 50,000 to 60,000 downloads to make the list, says GTekna CEO Chang-Min Pak, so to marshal downloads the company resorted to bribery. It placed ads on websites that had large, active communities. People who clicked through the ads and downloaded apps were awarded points they could redeem for gift cards. In 2012 and 2013, Apple banned GTekna from the App Store and cracked down on similar apps.

A few upstart companies, including one called AppsBoost, have taken GTekna’s place. AppsBoost currently charges developers $20,000 to drive an app into the App Store’s top 25 free apps for a period of 48 hours, $12,000 to get an app into the top 50, and $8,000 for the top 100. An AppsBoost representative confirmed the company follows GTekna’s old model of rewarding consumers with a piece of content or virtual currency for downloading a client’s app.

Even shadier are the app promotion firms that employ “Internet water armies” of low-paid people in China and India to download apps. The name “water army” is a rough translation of a Chinese phrase and refers to these groups’ ability to flood a specified website—or app—with high ratings, positive comments, votes, clicks, or downloads. Sometimes humans aren’t even involved. There are firms in China that use automated software “bots” to download apps in massive numbers. When Flappy Bird, a free, ad-supported game that navigated a bird around obstacles, went viral in early 2014, people suspected bots had helped it notch more than 50 million downloads in just a few months.61 Its developer has stated he said he doesn’t “do promotion,”62 but did not specifically deny the allegations and later pulled it from app stores.63

These “appayola” schemes are a niche business. VisionMobile, which tracks developer usage of third-party tools in annual surveys, says only 7 percent of developers reported they were utilizing any type of “cross promotion networks” to boost their apps in 201364 and the GTekna/AppsBoost brand of cross-promotion would be a smaller subset of that category. Such systems are ultimately unsustainable. “Once everyone [starts paying for downloads], the only way you can win is to put more and more money into it,” says Vakulenko. “Eventually, the whole return-on-investment breaks down, and people start relying on it less and less.”

Apple, naturally, despises appayola. Besides booting rogue developers from its iOS Developer Program, which essentially ends their careers as iPhone developers, Apple occasionally changes its App Store algorithms to thwart manipulation. Recent evidence suggests Apple’s ranking now incorporates factors such as app rating, user retention, and user engagement as well as download volume and velocity,65 though the weight it gives them is a matter of industry debate; Palli says Apple is “making tweaks,” but has not instituted “core changes.” The cat-and-mouse game between Apple and developers will continue.

FIGHTING FAKE PHONES

It’s not just the app stores. Smartphone manufacturing and sales have a dark side. Counterfeiting and smuggling is pervasive in poorly regulated emerging economies. The fight to keep fake phones off the market is a front in a different type of smartphone war that pits opportunistic lawbreakers against smartphone makers and platform providers.

Smartphones are an ideal target for counterfeiters. All consumer electronics get knocked off, but smartphones are in a class of their own. Compared to other gadgets, they are in greater demand, command higher value, and are more portable. The global nature of the smartphone business, which spans hundreds of suppliers and subcontractors across multiple countries, also gives copycats ample opportunities to intercept phone designs and parts. As an April 2013 report about East Asian counterfeit goods from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime put it:

Gone are the days when manufacturers could shutter their plants and guard trade secrets. Today, those who hold intellectual property rights are often situated half a world away from those who make their ideas come to life. . . . In effect, counterfeit goods are an untallied cost of the growth in offshore manufacturing.66