Every day, when Todd Dunphy checks his e-mail, he finds messages from people begging for assistance with their smartphone plans. One December 2013 e-mail came from a person who was paying $1,200 a year for unlimited service but only using 150 voice minutes, 25 text messages, and a scant amount of mobile data each month. The issue wasn’t the person’s smartphone—a Galaxy S model that the phone’s owner liked—but the expense of the accompanying plan. “I just feel like I am paying so much money for services I don’t use, but [I can’t] find a very good [alternative] option,” the owner explained. “Please help!!!”

Dunphy has been receiving these kinds of “Please help!!!” e-mails for years. He is a former Verizon Wireless salesman, and in 2007 he co-founded a mobile analytics firm called Validas to save people and consumers money on their wireless service. The Houston, Texas–based company analyzes the cellphone bills of companies, government agencies, and consumers for extraneous charges using its own software. As a result, Validas claims to now have amassed the largest collection of wireless bill information in the United States outside of the carriers.

Sifting through the data, the company says the biggest trend in spending habits is wireless waste—the gap between the service capacity people sign up for and the amount of that service they actually use. Says Dunphy, “The only way I win, as a smartphone consumer, is when I perfectly buy and use [an exact number of gigabytes], which never happens.”

We all like to think we’re savvy shoppers. Yet Validas’s data shows that most of us spend more than we need to on wireless service month after month, year after year. Validas estimates 80 percent of American wireless subscribers are paying carriers $200 a year for excess minutes, messages, and data. On a national level that adds up to $52.8 billion of wireless waste a year. On a global level the figure could be as high as $926 billion, Dunphy says. Smartphones are the biggest source of wireless waste, because their plans are particularly expensive and complicated. According to Validas they are responsible for $45 billion, or 85 percent, of the United States’ total overspending on wireless service.

As a company that aims to lower its clients’ mobile costs, Validas has business incentives to call attention to wireless waste, and potentially to overstate its scope. But others in the industry agree that wireless waste is a problem. A New York–based company called Alekstra, which was founded by a former Nokia executive and provides services similar to those of Validas, has estimated that U.S. wireless waste is as high as $70 billion.1 A 2013 Consumer Reports survey of more than 58,000 of the publication’s subscribers found 38 percent of its respondents were using half or less than half of their monthly data allowance.2 Logan Abbott, president of MyRatePlan.com, a comparison-shopping site for wireless plans, says the vast majority of consumers don’t use all the data or minutes they’re allotted.

How do we end up with these supersized smartphone plans? The short answer is that carriers keep pushing us into pricier plans to maximize their profits. The carriers wouldn’t phrase it that way, but industry analysts say carriers are wringing more money out of their subscribers to counteract slowing growth. For years carriers grew by just signing up people who were brand-new to wireless service, but now virtually every American who wants and can afford a cellphone has one. Carriers can still boost their revenues by upgrading subscribers from basic cellphones to smartphones, which require more expensive service plans, but that group is dwindling, too. More than 65 percent of Americans already have smartphones.

Carriers are now primarily concerned with maintaining or increasing profitability, which, until recently, has meant cutting operational costs and raising rates on their smartphone subscribers. Smartphone users are obvious targets. Just by purchasing smartphones users indicate they are more capable of spending, or at least more likely to spend, than basic cellphone users.

THE PRICE OF MOBILE DATA

When estimating the cost of smartphone ownership, many consumers focus on the upfront cost of new smartphones rather than on the price of the accompanying plans. But the devices cost much less than the plans, which are a recurring expense.

Carriers sell two basic types of service plans: postpaid and prepaid. Postpaid plans are contractual agreements between subscribers and carriers, with carriers billing subscribers for service at the end of each month. Carriers traditionally gave postpaid subscribers deep subsidies on new phones. Since subsidies average around $400, and carriers typically price new smartphones somewhere between $0 and $250, carriers actually lost money each time they sold a subsidized smartphone. To ensure they recoup their costs and turn a profit, carriers make these subscribers agree to purchase service from them for a set period of time, usually two years.

With prepaid plans, customers pay for service in advance, by either purchasing credits for set allotments of voice minutes, text messages, and data bytes or prepaying for a bundle of services per day or month. Prepaid users also buy their phones on their own. Since carriers don’t take on any financial risk with prepaid plans, users aren’t required to sign contracts.

In many regions, such as Africa and Latin America, prepaid plans are more prevalent, but in the United States postpaid plans are more common, especially for smartphone owners. About two thirds of U.S. cellphone users are on postpaid plans and one third are on prepaid plans. To carriers, postpaid customers are more valuable, because they generate more revenue.

The future of the carrier business lies in mobile data. Carriers in the United States and a few other countries, such as Japan, already make more money from data than voice services and most U.S. carriers now automatically include unlimited voice in their smartphone plans. As the Wall Street Journal pointed out in October 2013, “The carriers aren’t making this change because they think customers should just have unlimited calls for free. . . . Focusing on data and giving everything else away seemingly as a freebie actually centers the companies on their main source of revenue growth.”3 Mobile data is a $90 billion market in the United States alone; globally, it is worth about $400 billion.4

Smartphones and data plans are inextricably linked. For the most part, carriers won’t let consumers buy smartphones without signing up for mobile data plans. Asymco analyst Horace Dediu calls the iPhone a “mobile broadband salesman.” Carriers “hire” the iPhone to sell mobile data plans to consumers, and the phone’s job is to move people from $50-a-month plans to $100-a-month plans by transitioning them from basic to smartphones. The prices that carriers pay Apple are essentially sales commissions for accomplishing this job. “Apple gets a huge commission in the form of a price premium and subsidy on the iPhone,” Dediu explains. “It’s the carriers saying, ‘Thanks, you’ve helped us attract more customers to our most profitable service plans.’”

Those service plans can change frequently, in both composition and price. Carriers are comfortable raising rates, because they know consumers are dependent on their smartphones and apps and many are locked into multiyear contracts. “Smartphones are close to a life necessity now,” says Dunphy. “It’s become ‘food, water, shelter,’ and ‘Do I have my phone with me?,’ and the carriers know that.”

One common carrier move is to kill unlimited data plans. A few years before the iPhone was unveiled, carriers started rolling out 3G technology, which increased their capacity to support mobile data usage. To spur consumers to access the mobile Internet on their phones, they introduced unlimited plans at affordable rates. But iPhone, Android, and other smartphone users started sucking up more bandwidth than anticipated. “Unlimited plans became the operators’ arch enemy,” says Jake Saunders, ABI Research’s vice president of forecasting. “Operators were blindsided by the small percentage of users who took those plans to the ultimate limit.” In response, AT&T and Verizon adopted tiered pricing to safeguard their networks and profits: subscribers select the amount, or “tier,” of voice minutes, text messages, and data they believe they will use per month. Subscribers who consume more than their allotments are charged a high rate for extra data usage.

Today only 12 percent of mobile subscribers around the world have access to unlimited “all you can eat” data plans, down from 15 percent in mid-2013, according to ABI Research. Tiered, wage-based plans are much more prevalent—they are available to 64 percent of mobile subscribers globally. In fact, unlimited data has become so rare that Sprint launched an unlimited guarantee policy in 2013 and is touting it as a major asset for its customers. But how long can Sprint buck the industry trend toward tiered plans? Sprint has fewer subscribers than AT&T and Verizon, so it has more bandwidth to support unlimited plans. Following its 2013 merger with the Japanese carrier SoftBank (Japan’s number-three carrier and now owner of about 80 percent of Sprint), the formerly cash-strapped Sprint also now has funds it can use for network upgrades and maintenance. Deepa Karthikeyan, an analyst for the market research company Current Analysis, says Sprint has to “pull out all stops to create a strong differentiator against the leading carriers,” for the next couple of years. But if it “gains critical traction” in the marketplace and no longer needs such enticements to lure consumers away from its rivals, she thinks Sprint may stop offering its unlimited guarantee to new customers. In a sign that Sprint is seeing network congestion, it recently warned its top 5 percent of data users that it may start reducing their mobile throughput speeds “during heavy usage times” to keep connections fast for other customers.5

When AT&T first adopted tiered pricing, the company said the change would “make the mobile Internet more affordable to more people,”6 because its lowest data tiers cost less than the unlimited plans they were replacing. That was true, but the catch is that bandwidth consumption is escalating as smartphones gain features, a wider range of high-definition media launch, and data connections get faster. Karthikeyan says that “the overall smartphone experience” keeps improving for consumers, but they are also spending more on tiered pricing plans. Subscribers may start out paying relatively little in the lowest tiers, but they quickly move up to more expensive ones, because they need more data and they are charged overage fees if they exceed data caps.

Carriers have also been increasing data prices. Consider the short history of AT&T’s data plans for the iPhone. The iPhone launched in 2007 with a $20 unlimited data plan. A year later, when the iPhone 3G debuted, AT&T upped the price of unlimited data to $30. In June 2010, AT&T switched to tiered pricing, which meant new iPhone 4 buyers had to choose between paying $15 for 200 MB or $25 for 2 GB. Today an individual AT&T iPhone user can still pay $20 for data but will get only 300 MB, and buying 2 GB costs $40. Verizon’s plans have followed a similar trajectory and are even more expensive. Until July 2011, unlimited data on Verizon cost $30. After it moved to tiered plans, $30 bought 2 GB. As of May 2014, $30 will buy 500 MB on Verizon, and 2 GB costs $50.*

New types of mobile data plans can cost consumers even more. Multidevice shared-data plans allow subscribers to use a set amount of 4G LTE data among different types of devices and pay only one monthly fee. These plans look pragmatic on paper, since the costs and data can be divvied up many ways, including among family members. But analysts say the plans can easily accelerate consumers’ data consumption and costs, on top of which they must pay a monthly line access fee for each device (independent of data usage). The result is that these plans end up being 10 percent to 15 percent more expensive than other mobile data options, according to Saunders.

Multidevice plans are also more effective at locking in subscribers, since it’s more complicated to switch service and carriers when multiple devices and people are involved. Ralph de la Vega, the president and CEO of AT&T’s wireless business, has described the company’s Mobile Share plans as “a good plan for us from a loyalty point of view.”7 AT&T showed its enthusiasm for multidevice shared-data plans in October 2013 when it dropped its regular tiered plans and began requiring new subscribers to sign up for Mobile Share plans. Only 9 percent of global mobile subscribers currently have access to multidevice shared-data plans but that number has nearly doubled since May 2013, showing that carriers are quickly adopting this newer type of plan. Saunders expects more carriers will follow, noting, “Operators realize . . . they can get more money out of the user” with them.

Consumers would make better choices if they understood what they were buying. In July 2013, AT&T, Sprint, T-Mobile, and Verizon offered a total of nearly 700 combinations of smartphone plans, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis.8 Which plan is best? The only honest answer is: it depends. Dunphy advises consumers to buy voice minutes, text messages, and data the same way they buy milk. He means that people should take more care to buy only what they need, since anything left over will be thrown away (or taken away by the carriers, in the case of wireless plans). “Smartphone plans are supercomplicated, with lots of variations,” admits Dunphy. “But we’re trying to get people to think about the way they buy other things in life and apply that thinking to their wireless plans.”

The problem is that mobile data is not sold the way most products are. In order to select a data tier, consumers must estimate how much bandwidth they will use in a month. But most people have no idea how to quantify mobile data, which can fluctuate due to a number of variables. An e-mail with attachments takes up more bandwidth than a text-only e-mail. Browsing graphic-heavy, video-enabled websites requires more data than surfing simple sites. Streaming video over 4G is more bandwidth-intensive than 3G video. Streaming high-definition video can eat up more than twice the amount of data as standard video.

Even carriers disagree about the amount of data a particular activity will consume. Verizon says downloading a song will eat up 7 MB; AT&T says 4 MB. Verizon says sending a text-only e-mail should take 10 KB; AT&T and Sprint say 20 KB. AT&T estimates video streaming will consume 2 MB a minute; Sprint and Verizon say it’s more than double that, on average. The three companies also list different rates for music streaming (500 KB or 1 MB per minute) and Web surfing (either 256 KB, 400 KB, or 500 KB per page). These are just estimates, which will vary by smartphone model and operating system, and which reflect technological differences between the networks, such as download and upload speeds. Nevertheless, the variance between the carriers’ numbers may increase consumer confusion about data rates and consumption.

Uncertainty breeds risk aversion. People overspend because they are anxious they will exceed their voice and data quotas. Most consumers would rather oversubscribe and know they’ll stay within their plans’ bounds than pay less and have to worry about penalties. Carriers may stoke those fears to make more money. “Sales reps will say, ‘Go with a fifteen GB plan; you have a teenager, you need that,’ [even if you don’t],” says Dunphy. He blames the industry’s sales commission system, which he claims has not changed much since he worked in a New Jersey Verizon Wireless store in the early 2000s. He says: “Every single thing [your carrier sells you], someone is getting a commission on. When a sales rep sells you a higher plan when you should be on a lower plan, it’s because he’s getting paid based on the size of that plan. The system is built like that. Your bill is directly tied to commission.”

Carrier Economics

Carriers say they need to charge more because their upfront expenses keep mounting. Bandwidth alone is a huge cost. Cisco, the data-networking giant, says smartphones devour 48 times more mobile data than basic phones, because people use them more like computers—surfing the Web, uploading photos to Facebook and Instagram, and streaming music from Pandora. AT&T says mobile data traffic on its network increased more than 30,000 percent between 2007, the year it launched the iPhone, and 2012. Ericsson’s latest Mobility Report, which it publishes annually based on data from its mobile networking business, forecasts that global smartphone traffic will grow 10 times between 2013 and 2019, when it will reach 10 exabytes, or 10 billion gigabytes per month.9

To keep pace, carriers are spending billions on wireless spectrum—a broad swath of radio frequencies that can carry a variety of communications information, from radio to TV to smartphone signals. Spectrum is a finite resource, so demand far outweighs supply. The government is responsible for allocating spectrum—to carriers, broadcasters, the military, police, emergency medical technicians, and other groups—and licenses for its usage can be purchased in government-hosted auctions or in company-to-company deals. These can cost millions or even billions of dollars. In 2012, Verizon paid four cable companies, including Comcast and Time Warner Cable, $3.9 billion for spectrum with nearly national coverage. In 2013, Sprint paid U.S. Cellular, the country’s number five carrier, $480 million for spectrum in the Midwest, and AT&T paid Verizon $1.9 billion for spectrum Verizon was not using in 18 states. In 2014, T-Mobile bought some more of Verizon’s unused spectrum, in several places across the country, for $2.4 billion in cash and spectrum swaps. Carriers pay these huge sums because spectrum gives them capacity to support their users; running low leads to dropped calls and data slowdowns on their networks. People in the wireless industry often call spectrum the lifeblood of mobile communications.

The spectrum shortage is driving expensive mergers and acquisitions. In 2013, T-Mobile spent $1.5 billion to merge with the midsize carrier MetroPCS and Sprint paid $3.5 billion to acquire the portion (approximately 49 percent) of the wireless broadband provider Clearwire it didn’t already own. In 2014 AT&T purchased the midsize carrier Leap Communications for $1.2 billion. The buyers gained new subscribers and other assets, but a need for spectrum drove the deals. As the tech news site Gigaom put it, “The big four [carriers] are becoming chop shops, buying up smaller players and stripping them to get at their airwaves.”10

To stay competitive, carriers have also spent billions upgrading their networks to LTE, to be faster and more efficient. Even after a carrier has rolled out an LTE network nationally, it still needs to continually expand capacity because speeds dip as more smartphones move onto the network. Faster networks also enable people to do more on their smartphones, which further increases traffic on networks, necessitating even more equipment upgrades and spectrum purchases. Cisco estimates that a 4G-connected smartphone generates more than three times more traffic than a smartphone on a slower connection. Verizon has said its LTE users consume more than twice the amount of mobile data as its 3G customers. U.S. carriers spent $11 billion on LTE equipment and software in 2013, according to the technology research firm iGR, and will spend a cumulative $38 billion on LTE equipment and installation, as well as $57 billion to keep their networks running, through 2018.

Billion-dollar infrastructure investments have divided carriers into classes. AT&T and Verizon, which together hold about 67 percent of the U.S. wireless market, have more than enough subscribers and revenue from subscriber fees to offset their costs. Verizon reported a healthy 49.5 percent wireless service margin in 2013, and AT&T’s wireless margin for the year was 41 percent. For smaller carriers, such as Sprint and T-Mobile, which hold 16 percent and 14 percent of the U.S. wireless market, respectively, “the picture is much bleaker,” says Greg Linden, a researcher at the University of California, Irvine, who has studied the economics of the smartphone industry.

Sprint and T-Mobile executives have publicly argued that they should be allowed to combine forces to narrow AT&T and Verizon’s lead. In separate February 2014 calls with analysts, T-Mobile CEO John Legere said, “Over time, this industry is ripe for the impact of further consolidation,” and Sprint CEO Dan Hesse asserted that “further consolidation in the U.S. wireless industry”—outside of AT&T and Verizon—would improve the wireless industry’s “competitive dynamic” and be “better for the country and better for consumers.”11 But a Sprint–T-Mobile merger would likely rouse government resistance, if not opposition, due to antitrust concerns. Both the FCC and the Justice Department have stated that they believe the U.S. wireless industry needs four large carriers to remain competitive.

One issue that unites all carriers is their frustration with popular, bandwidth-heavy services such as Netflix and YouTube. Carriers call these services over-the-top, or OTT, because they run on top of their networks and cause congestion without paying for the data traffic they create. In October 2013, Google said that 40 percent of YouTube’s traffic comes from mobile devices, including smartphones, up from 25 percent in 2012 and 6 percent in 2011. Verizon recently said video accounted for 50 percent of its wireless traffic and will rise to 66 percent by 2017. Michael O’Hara, chief marketing officer of the GSMA industry group of carriers and related companies, says, “There’s a disconnect between the [network] investment required by operators and [the fact that] the revenues generated [from the networks] are predominantly flowing to content companies.”

Carriers have struggled for years with this conundrum. In some areas of the world, they have struck deals with the OTT service providers clogging their networks. Google has paid Orange, the France-based carrier, an undisclosed fee since 2012 for the (mostly YouTube-related) traffic it sends across Orange’s network.12 The idea that payments for mobile services can and should be differentiated could pave the way for a number of future pricing changes, depending on the local “network neutrality” rules. (Those rules are currently in flux in the United States.) Dunphy thinks American smartphone bills will eventually resemble cable bills, with OTT services priced separately and bundled into packages similar to the way cable companies charge for channels. “Carriers could have a package in which you get 2 GB and all your Facebook and Twitter [access] included,” explains Dunphy. “To get YouTube, they might make you pick the highest plan.”

THE UN-CARRIER MOVEMENT

It’s easy to criticize carriers—and many people do. Carriers’ customer satisfaction and corporate reputation ratings are usually dismal. Telecommunications companies ranked number 15 out of 17 industries in a 2013 survey commissioned by the Reputation Institute, a New York City–based advisory firm that provides “reputation consulting.”13 Its rating suggests American consumers view telecom companies as even less reputable than the pharmaceutical, utility, airline, and energy industries, and only more reputable than banks and “diversified” financial companies. Some carriers are aware of this. In a speech at an industry conference in 2012, Sprint CEO Dan Hesse lamented the situation, saying, “[E]ven the cable and oil industries rate higher with consumers than we do.”14 Many American smartphone users, however, would probably sympathize more with cellphone inventor Martin Cooper when he says: “I spent my whole life battling with carriers. They come out of a monopoly environment and try to tell you what you want. The motivation of every carrier is to get customers to spend as much money on their networks as possible. We’ve built a system where the motivations of carriers are counter to the public interest.”

There are a couple of areas in which the Big Four carriers—AT&T, Sprint, T-Mobile, and Verizon—are slowly becoming more consumer-friendly: phone subsidies and upgrade policies. On the one hand, carriers want customers to upgrade their phones, because upgrades keep customers locked into contracts and loyal. On the other hand, carriers don’t like paying subsidies for phone upgrades. They didn’t mind fronting that cost when a lot of their customers were switching from basic to smartphones and from 3G smartphones to 4G smartphones, because those changes led to more data usage, giving carriers a revenue boost. But now that consumers are upgrading from 4G smartphones to other 4G smartphones, carriers get smaller payoffs from footing subsidies. In December 2013, AT&T CEO Randall Stephenson told an investor conference that the phone subsidy model “has to change” because carriers are now in “maintenance mode” and “can’t afford to subsidize devices [aggressively]” anymore, according to CNET.15 ABI says subsidies are carriers’ single largest cost over the lifetime of a subscriber’s contract, eating up 68 percent of the revenue derived from a typical 24-month service agreement.

Between 2011 and 2013, carriers have rolled out a number of changes to reduce their subsidy expenses and improve their margins, including altering their discount, fee, and eligibility policies to discourage upgrades. In January 2011 Verizon canceled its long-standing New Every Two program, which let subscribers shave $30 to $100 off the already discounted price of a new phone if they had completed at least 20 months of their two-year contracts. In 2011 and 2012, AT&T, Sprint, and Verizon increased the upgrade fees they charged subscribers who bought new phones on subsidy. Those fees now hover between $30 and $36, about double what they were in 2011. In 2013, AT&T and Verizon lengthened the amount of contract time subscribers must complete to qualify for subsidized upgrades (from 20 months to 24). To thwart subscribers from acquiring new phones on subsidy and leaving early, AT&T, Sprint, and Verizon also raised the early termination fees (ETF) they charge subscribers who don’t fulfill their two-year service contracts. ETFs for smartphone users have doubled since 2009, from about $175 to as much as $350.

In 2013, after years of instituting higher fees, longer upgrade cycles, and stiffer penalties, the wireless industry started emphasizing lower prices and greater consumer choice. T-Mobile has been one catalyst for change. Under CEO John Legere, who assumed his post in September 2012, T-Mobile is trying to improve its perennially fourth-place prospects by branding itself as a maverick “un-carrier.” As an “un-carrier,” T-Mobile purports to “break the rules” of the “out-of-touch wireless carrier club” and take the customer’s side.16 As Dunphy puts it, “T-Mobile basically said, ‘What does everyone hate about wireless service in the U.S.? Let’s say we agree with all those things and introduce new policies to combat them.’”

T-Mobile kicked off its un-carrier strategy by slashing prices and eliminating conventional subscriber contracts and subsidies. T-Mobile’s Simple Choice plans, which launched in March 2013, sell smartphones at full price and let customers pay off the cost through monthly installments, usually over two years. The setup is similar to 0 percent financing for a car. T-Mobile customers pay for their voice, text message, and data service via a separate monthly fee.

The Simple Choice plans relieve T-Mobile of the burden of subsidizing new smartphones while giving consumers a manageable way to pay down their phone expenses over time. The setup also saves consumers money. Most people don’t realize it, but approximately $20 of a traditional postpaid monthly smartphone bill compensates the carrier for its phone subsidy. That $20 doesn’t show up as a separate line item on subscribers’ bills, but it is included in their overall monthly fees. Since the subsidy reimbursement is built into subscribers’ monthly bills, carriers continue charging it even after they recoup their subsidy costs, which usually happens between the twentieth and the twenty-second month of a two-year contract. “Carriers end up making an extra $20 a month on your contract,” says Sina Khanifar, an activist who advocates for consumer rights in tech matters. “It’s a big financial game that relies on consumers not understanding the economics.”

Since T-Mobile charges lower service rates than its competitors, its customers save money immediately and increase their savings the longer they hold on to their phones. T-Mobile’s strategy also lets customers see how much their phone really costs, how much their service really costs, and how close they are to paying off their phones. David Pogue, in a New York Times review, said T-Mobile’s policies were “much more fair, transparent, [and] logical” than other carriers’ policies.17

Critics say T-Mobile’s Simple Choice plans are less radical than the carrier professes. The company calls the plans “no contract” and “contract-less,” because customers can leave any time they want. But customers must pay the remaining balance on their phones when they leave. As CNET has noted, the device payment agreement essentially acts like an early termination fee, which means, “For many, the monthly installments constitute another contract, just one that’s worded in a different way.”18 In April 2013, the attorney general in Washington state, where T-Mobile is based, accused the company of deceptive advertising for “promis[ing] consumers no annual contracts while carrying hidden charges for early termination of phone plans.”19 In the resulting court-ordered agreement T-Mobile agreed to state “the true cost” of its phones more clearly in its ads.20

Consumers have largely embraced T-Mobile’s un-carrier changes, which also included the introduction of an early-upgrade plan for people who want to change their smartphones frequently, and free, unlimited data for Simple Choice subscribers in more than 100 foreign countries, and eliminating overage fees for customers who exceed their plan limits. In 2013, the carrier began signing up more new postpaid customers than it lost for the first time in four years. In a January 2014 note to investors, Barclays Capital telecom analyst Amir Rozwadowski said T-Mobile’s gains, which amounted to more than 2 million T-Mobile-branded postpaid (net) subscribers in 2013, were “better than expected” and “clearly indicate that its un-carrier strategy continues to resonate with subscribers.”*21

Competitors reacted by lowering prices, increasing data allotments, and introducing more flexible plans that let consumers upgrade phones faster and opt out of long-term service contracts provided they paid full price for their smartphones or acquired them on their own. To emphasize the changes, AT&T and Verizon renamed their plans—to Mobile Share Value and More Everything, respectively. While FierceWireless, an influential wireless industry newsletter and news site, cautioned against calling the changes a “price war,”22 because the discounts weren’t drastic and the consumers who saved money on service fees were also paying more for their smartphones, a New York Times article said T-Mobile’s success had put “the other carriers in somewhat of a defensive crouch.”23

Though T-Mobile’s un-carrier policies are a conspicuous new influence in the wireless industry, they are not the only force driving change. The demographics and economics of the maturing U.S. smartphone industry are also prompting these moves. As Rozwadowski has written, “Smartphone penetration has clearly surpassed the steep part of the adoption curve for the overall market with the remaining growth coming from . . . more price sensitive subscribers.”24

Amina Fazlullah, policy director at the Benton Foundation, a Washington, D.C.–based nonprofit that advocates for the public interest use of communications technologies, says U.S. carriers are realizing they need to offer lower prices and more consumer-friendly provisions to keep growing. Fazlullah says: “Because T-Mobile and [to some extent] Sprint have taken more aggressive stances on trying to compete on a consumer-friendly scale to attract consumers, we’ve seen AT&T and Verizon try to soften their stance and try different ways to bring people in, too. A piece of this is driven by [industry] competition, but also the reality that this is the last group of untapped [smartphone] consumers. Every carrier knows the last frontier for [smartphone] penetration is vulnerable populations, such as low-income Americans and minorities. New customers will be in those socioeconomic groups, and they need more flexibility and the ability to back out of a service if they have a change in income. There’s no way for those families to sign up for services that are incredibly expensive and really lock you down.”

UNLOCKING

Consumer advocates say unlocking phones—breaking the software locks that tie phones to a single network—is one way to reduce costs for consumers. “Unlocking is a way to let vulnerable populations’ dollars go further,” says Fazlullah. “It lets people go from provider to provider and decide who’s giving them a better deal while being able to retain their phones.” Unlocking phones also helps international travelers save money by enabling them to change their SIM cards to those of a local carrier and avoid roaming fees.

People have been unlocking cellphones since the early 2000s, but unlocking has always occupied a legal gray zone due to the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), a wide-ranging copyright protection law Congress passed in 1998. Though the DMCA was designed to prevent people from illegally copying and distributing music and movies, the government has interpreted the law’s anti-circumvention provisions to also prohibit unlocking. These provisions, which appear in Section 1201 of the DMCA, outlaw people from tampering with software locks that control access to copyrighted works. Since a smartphone’s software can be copyrighted, disabling or removing the locks that carriers or phone makers place on that software in order to prevent user access can be considered a breach of the DMCA.

Consumer advocacy groups have long protested this interpretation. They argue that copyright law is being erroneously applied to a situation in which there is no copyright infringement or content piracy. “It’s a weird loophole,” says digital rights activist Sina Khanifar. “The language used in the DMCA makes the law incredibly encompassing.”

Khanifar is a San Francisco–based software programmer and technology entrepreneur and one of the leading advocates of unlocking. About a decade ago he established a small unlocking business to help pay his college bills, but he stopped in 2005 when Motorola sent him a cease-and-desist order. Khanifar says that at the time he was 20 years old and terrified at the prospect of being punished under the DMCA, which carries penalties of up to $500,000 in fines and five years in jail per offense. Motorola eventually dropped the case after the prominent civil liberties attorney Jennifer Granick—currently the Director of Civil Liberties at Stanford Law School’s Center for Internet and Society—gave Khanifar pro bono legal help. Khanifar emerged convinced that companies were leveraging the DMCA to squeeze consumers and entrepreneurs.

After Granick assisted Khanifar, she and other civil liberties activists pressed the Library of Congress, which oversees the U.S. Copyright Office, for an exemption to the DMCA’s anticircumvention rules. As head of the Library of Congress, the Librarian of Congress has power to issue DMCA exemptions, but the exemptions expire after three years. Activists wrangled an exemption in 2006 and again in 2009. But in October 2012, Congressional Librarian James Hadley Billington reversed his position, citing the “ready availability of new unlocked phones in the marketplace,”25 presumably from retailers like Amazon and Best Buy. By January 2013, it was no longer legal to unlock new cellphones.

Consumer advocates are battling that decision through grassroots campaigns. They worry that the ruling sets a dangerous precedent for government intrusion in people’s lives and belongings. “The question is, when you buy a phone, do you really own it and its software, and can you modify it?” says Khanifar.

In early 2013, Khanifar started an online petition that requested the White House to legalize unlocking. The petition resonated with “the pretty large percentage of people who have had the experience of trying to change [cellular] networks and not being able to,” said Khanifar, and it amassed more than 114,000 signatures in 30 days. In response, the Obama administration issued a supportive letter that said it was “common sense” that “consumers should be able to unlock their cellphones without risking criminal or other penalties.”26

About six months later, the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA), a Commerce Department agency that advises the president on telecommunications and information policy issues, formally asked the FCC to require carriers to unlock consumers’ devices upon request. That sparked negotiations between the FCC and the Cellular Telecommunications and Internet Association (CTIA), the main trade group for the U.S. wireless industry. At the time, most U.S. carriers already allowed some of their subscribers to unlock their phones, but they hesitated to publicize or liberalize their policies, because unlocking conflicts with their business models. On the postpaid side, unlocking threatens the carrier practice of recouping phone subsidies by signing subscribers to exclusive, multiyear contracts. On the prepaid side, unlocking makes it easier for shady businesses to buy mass quantities of prepaid phones that have been slightly subsidized for marketing purposes, unlock the phones, and sell them for profit. “Consumers and consumer advocacy groups are the only ones who fight for unlocking,” says Khanifar. “No big companies ask for it; all the money is on the other side of the table.”

In the end, the FCC delivered an ultimatum: “It is now time for the industry to act voluntarily or for the FCC to regulate.”27 In December 2013, the country’s five largest carriers—AT&T, Sprint, T-Mobile, U.S. Cellular, and Verizon Wireless—committed to adopting six standards related to unlocking. By March 2014, the carriers had posted their unlocking policies on their websites and started unlocking postpaid and prepaid smartphones and tablets for eligible consumers who requested the service. People on postpaid smartphone plans qualify for carrier unlocking only if they have completed their two-year service contracts, fully paid off their phones on a no-subsidy financing plan, or paid an ETF to get out of their contracts early. Still to come: a system that either notifies subscribers when their devices qualify for unlocking or automatically unlocks the devices remotely; a reduction in the time needed to respond to unlocking requests to two business days; and a process for unlocking devices for military personnel who show proof of overseas deployment.

Khanifar says the CTIA agreement is “definitely a victory” for his campaign, because the new policies and principles will simplify and expedite smartphone unlocking through carriers. But he cautions that it is “only a start,” because the reforms don’t challenge the carriers’ central role in unlocking phones. Khanifar’s philosophy is simple: “Once you buy something, you should be able to do with it what you want.” By leaving carriers in charge of phone unlocking, the CTIA agreement stops far short of that standard.

Activists are hoping federal legislation will give consumers more control. Until early 2014, Khanifar and his colleagues had backed the Unlocking Consumer Choice and Wireless Competition Act proposed by Senator Patrick Leahy (D-VT) and Representative Bob Goodlatte (R-VA) in March 2013. The Leahy-Goodlatte bill legalizes unlocking only until 2015, when the Librarian of Congress is scheduled to revisit the issue yet again. The tech news site Techdirt said the bill “just punts the issue until later.”28

But the bill also had two things going for it. It was the most likely to get passed, and it seemed to address a point often overlooked in laws related to unlocking: the need to legalize unlocking as both a business and an individual right. Unlocking requires modifying a phone’s software, which consumers can do by downloading and running a special program or by punching in a code purchased online that updates the phone’s settings. The first method can be tricky, so for many smartphone users the right to unlock their phones is useless unless they can also hire professionals to do the unlocking for them. But under the DMCA, people who unlock other people’s phones face the same penalties Khanifar did in 2005, because they are considered to be violating the law “willfully and for purposes of commercial advantage or private financial gain.”29 Even the Librarian of Congress’s exemptions technically permitted individuals to unlock only their own phones.

The threat of a DMCA penalty keeps big companies out of the unlocking business. The shops that do unlock phones operate semi-underground. “It feels seedy to unlock phones,” says Parker Higgins, an activist at the digital rights nonprofit the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF). “That’s unfair for consumers; it should be a very straightforward thing.”

Activists thought the Leahy-Goodlatte bill was going to make unlocking straightforward because it allowed consumers to ask “another person” to unlock their phones, meaning users could solicit third-party service provider help, but in February 2014 Goodlatte amended it to exclude unlocking phones “for the purpose of bulk resale.” Such a policy was likely intended to thwart the unethical mass purchase and resale of new prepaid phones for profit, but it would also inhibit recyclers and refurbishers from unlocking and selling phones—a limitation that groups such as the EFF say would hurt consumers and the environment by restricting easy access to low-cost, used handsets.

Activists are now promoting another bill. Proposed in May 2013 by Representative Zoe Lofgren (D-CA), the Unlocking Technology Act aims to revise the DMCA so that nothing would be considered a DMCA violation unless it actually infringed copyrighted material. The bill would also add new language to the DMCA that explicitly states that unlocking is not infringement and thus is not a violation of it. “It’s really an ideal bill for solving unlocking and other DMCA problems,” says Khanifar. The bill is still in the committee review stage.

Activists plan to keep pushing for DMCA reform. Says Khanifar, “These are really important questions that are really central to how we will interact with technology going forward.”

PLANNED OBSOLESCENCE

Another type of waste occurs when smartphone makers prod consumers to buy new phones by quickly introducing more sophisticated replacements for current ones, discouraging repairs for those that are broken and malfunctioning, and phasing out software updates.

The iPhone is an oft-cited example of this planned obsolescence. People say Apple essentially replaces the iPhone each year by issuing a new model. Radical updates, such as changes to the phone’s screen size, only occur every two years, but each new iPhone offers enough improvements that a number of people ditch their serviceable, one-year-old iPhones every year.

People like iFixit CEO Kyle Wiens also say Apple makes it tricky to fix broken iPhones. iPhones are impressively durable, considering their elegant design, but their glass screens can crack if they are dropped onto hard surfaces. When the glass on an iPhone breaks, the phone’s liquid crystal display (LCD) often also needs to be replaced, because the glass and the LCD are glued together. In addition, Apple seals iPhone casings tightly, hindering access to its battery, which can be problematic because all smartphone batteries degrade over time and need to be replaced. Wiens says his iPhone 4S needed a new battery after 11 months, adding that “Apple makes very high-quality products, but it’s not interested much beyond the twelve- to twenty-four-month range.”

Of course, all smartphone makers prefer that consumers buy new phones instead of repairing their old ones. As the New York Times noted in an October 2013 article, the fact that Apple is accused of planned obsolescence more than most other companies is “partly a function of just how big a player it is, and how suspicious consumers become when a luxury product so closely associated with excellence doesn’t meet their expectations.”30 Apple has also tweaked the design of newer iPhones (the 5 and later) to make repairs easier and now offers screen replacements for the 5 and 5C as a convenient, while-you-wait service in its stores.

Whether or not the iPhone truly is an example of planned obsolescence, more smartphone makers are launching their phones the same way. HTC, Samsung, and others have established their own flagship smartphone “families” that they update annually with new models. HTC, LG, Motorola, and Samsung also complicate repairs in some of their phones by fusing the LCD to the glass screen or adhering other major components together. A number of new smartphones, including the HTC One (M8), Moto X, and the Nexus 5, lack easily removable batteries. In fact, iFixit considers the HTC One (M8) to be a far harder phone to repair than the iPhone 5C or 5S.

Planned obsolescence is also a software issue, and here Apple performs better than other smartphone makers. Apple typically supports iPhones with iOS updates for three years after launch. John Gruber, the influential Apple commentator, has argued that Apple’s comprehensive software upgrade policy proves that the idea that Apple “somehow booby-traps its devices to malfunction after a certain too-brief period to spur upgrades to brand-new products” is a “pernicious lie.”31 In a December 2013 post on his Daring Fireball website, Gruber pointed out, “Where is the mobile operating system that does a better job supporting older hardware than iOS?”32

In comparison, Android phone makers typically stop releasing updates 18 months postlaunch. Sometimes hardware limitations prevent software updates. For example, processors on older smartphones may not be robust enough to run newer operating system features. Carriers can also hold up smartphone makers’ software rollouts with lengthy approval procedures. But smartphone makers usually avoid updating their old phones for two other reasons: creating, testing, and distributing new software requires time and money, and they want consumers to buy new phones anyway.*

The silver lining of planned obsolescence is rapid innovation. The industry’s frenzied pace engenders faster, lighter, and more powerful smartphones every year, or even every few months. Software also gets more intuitive and intelligent with each upgrade. Consumers benefit from these improvements. But despite these perks, people such as Wiens deplore planned obsolescence, because it pushes consumers to spend money on new phones when at least some of them would be content with their current ones. Wiens would prefer that consumers repair their phones rather than replace them. “We’re on a freight train of consumerism,” says Wiens. “Manufacturers are pushing the pedal to the metal as fast as they can, and that’s not necessarily the best thing for consumers, the environment, or society.”

ESCALATING E-WASTE

When we rapidly upgrade and discard our smartphones, they contribute to the larger problem of electronic waste—a broad term applied to used electronics that have been thrown away, donated, or sold to a recycler. E-waste is one of the fastest-growing types of municipal solid waste, meaning waste created by and collected from houses and office buildings in towns and cities. A technology research firm, TechNavio, calculated that the world generated 58 to 63 million tons of e-waste in 2013. According to the StEP Initiative, a partnership of U.N. organizations, companies, governmental institutions, NGOs, and science organizations focused on fighting e-waste, global e-waste will reach 65.4 million tons a year by 2017.

Cellphones are one of the largest sources of e-waste, because people buy and throw out a disproportionately large number of them. Technological advances, wear and tear, design trends, marketing campaigns, and planned obsolescence make phones obsolete (or seem obsolete) faster than other gadgets. On average, Americans keep their cellphones for just 18 to 20 months. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)’s most recent e-waste report, Americans discarded an estimated 135 million mobile devices—meaning cellphones, smartphones, PDAs, and pagers—in 2010. That was more than four times the number of computers and more than five times the number of TVs Americans discarded that year.

Cellphones not only increase e-waste volume, they—like many e-waste materials—can be health hazards. Cellphone circuit boards and batteries usually contain at least one toxic metal, such as lead, which can cause neurological and developmental disorders; cadmium, which can result in kidney, bone, and lung disease; and beryllium, which is associated with lung and skin diseases. These toxic metals are safely contained when a phone is functioning but can be released when they are pulverized, incinerated, or buried in landfills.

Tracking e-waste has inherent challenges, and the lack of reliable data produces widely varying statistics. Estimates of the percentage of used American cellphones that are collected for recycling range from 60 percent (from a 2013 study by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Materials Systems Laboratory and the National Center for Electronics Recycling)33 to just 11 percent (the EPA). Once collected, a portion is sent overseas, but here too estimates run the gamut, with environmental advocates saying 50 percent of the e-waste collected by recyclers gets exported and the MIT/NCER study saying the amount is around 10 percent.

These various groups do, however, agree that at least some e-waste is exported. Like conflict minerals, it traverses the globe through a complex chain of people and companies, each propelled by its own motives. A typical chain might start with a dishonest e-waste collector pretending to hold a recycling fundraiser for charity. After people donate their used gadgets, the collector sells them to a broker. The broker then picks them up and ships them out of a nearby port—probably to Hong Kong. From Hong Kong, the cargo will probably get smuggled into China, to small companies that pay the brokers for the scrap.

This chain of events ends in places like the southeastern Chinese town of Guiyu, which is often called the world’s e-waste capital. China is a cost-effective place for Americans to send e-waste, because imported goods arrive constantly from China, and the enormous containers that carry them return relatively empty. “It doesn’t cost much to ship a load of stuff from New Jersey or Oakland, California, back to China,” says Michael Zhao, a video-journalist who made the documentary E-Waste: Afterlife, on e-waste in China, in 2011.

Guiyu’s proximity to Hong Kong and numerous Chinese factories make it a convenient spot to drop off international e-waste and resell it domestically. In fact, Guiyu and Foxconn City are located in the same Chinese province (Guangdong), about 180 miles apart from each other, and like Foxconn Guiyu relies on migrant labor from poor, rural provinces. “Probably, someone from their village said, ‘Hey, come here, it’s way better than tending a farm at home,’” says Zhao, who has visited Guiyu several times. Migrants may choose Guiyu over factory jobs, because the town’s system of small workshops, each of which typically employs fewer than ten people, allows families to live and work together.

Guiyu is home to 150,000 people who run and staff more than 300 companies and 3,000 individual workshops engaged in e-waste recycling. The town’s main trade is immediately obvious to any visitor. “On seemingly every street, laborers sit on the pavement outside workshops ripping out the guts of household appliances with hammers and drills,” said one CNN report. “The roads . . . are lined with bundles of plastic, wires, cables, and other garbage.”34

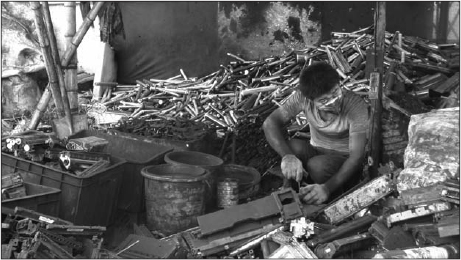

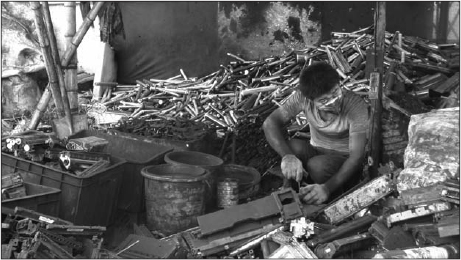

Guiyu laborers harvest these parts from computers, computer peripherals such as monitors and printers, TVs, and cellphones. Zhao says workers follow the same basic steps to disassemble both computers and phones. They remove the outer metal or plastic casing to uncover the circuit board and other components, then cook the circuit board to melt its solder. The cooking process produces toxic fumes, but it allows the chips to be removed from the board fully intact. Those chips are dusted off and resold, often under the pretense that they are new.

Worker dismantling toner cartridges, covered with toner, in Guiyu, China (Basel Action Network/Flickr)

When Zhao first visited Guiyu in 2006, he saw another set of workers immersing those circuit boards in buckets of burning acid to extract valuable metals, such as gold, silver, and copper. The buckets emitted thick, toxic smoke. Zhao’s film shows one of these workers warning onlookers, “Go away, you can’t handle this; it’s too choking. The sky is burning black.”35 Zhao recalls: “I tried to take a quick look at what was going on inside one of the vats, but the smoke burned my eyes immediately. . . . Those guys wear a pair of gloves [to protect their hands from the acid] and that’s it. I don’t know how they can deal with it for so long.”

Zhao says these acid vat plants paid more than Guiyu’s other entry-level e-waste jobs and thus were able to find willing workers. “These people are mostly concerned with economics,” explains Zhao. “They’re not thinking how bad their health will be ten years from now.”

Naturally there are health consequences to both living and working in Guiyu. The town has been processing e-waste since the early 1990s, and years of burning, melting, and acid-stripping e-waste have left the air, water, and soil polluted with lead and other toxic metals. “You smell Guiyu before you get there,” says Zhao. “It smells of burning wires and circuitry.” A 2010 study conducted by the nearby Shantou University Medical College found as many as eight out of ten Guiyu children had lead poisoning, which can affect mental and physical development.

The Chinese government banned the import of toxic e-waste back in 2000, but Guiyu continues to receive and process e-waste due to corruption. The local government reaps a “significant portion . . . of its annual revenues” from the practice and does not enforce regulation, according to a 2013 StEP Initiative report.36 “Beijing wants to get rid of [the illegal e-waste business], but the local government isn’t ready yet, because of economic considerations,” says Zhao. “If [local government officials] follow the rules, it’s basically death to the local economy, and they haven’t found another business to replace it.”

There has been progress. In 2013, China launched a ten-month campaign, Operation Green Fence, to firm up enforcement of its e-waste laws. The initiative stationed customs officials at Chinese ports to check the quality of foreign scrap. Shipments that exceeded the Chinese legal limit of 1.5 percent of contaminants were returned to their originating countries, causing a significant drop in e-waste imports. On Zhao’s most recent Guiyu trip, in 2013, he saw fewer dilapidated workshops and no acid vat plants. He says, “There are still piles of junk [on the ground], but they are much smaller and less obvious than a few years ago.”

Another change in recent years is that much of the e-waste in Guiyu now comes from within China. China’s burgeoning middle class is buying more gadgets, and the country is now home to at least 1.2 billion cellphones, many of which will be discarded in coming years. “People in cities often have two or even three cellphones at the same time, and they upgrade fast,” says Zhao. “China has become a major source of e-waste by itself, and the majority of these hundreds of millions of cellphones will stay in China.” The influx of domestic e-waste hinders Guiyu from implementing more sweeping environmental reforms. “The whole place is still built on this dirty process, and it’s not going to get really clean anytime soon,” says Zhao. “E-waste is an important issue, but there are so many other [health and safety] issues in China.”

Guiyu is one of China’s most internationally famous e-waste sites, but informal e-waste markets and slums exist elsewhere in China, and there are large e-waste dumps in or near Bangalore, Chennai, and New Delhi in India, Karachi in Pakistan, and Lagos in Nigeria. Agbogbloshie, a suburb in the Ghanaian city of Accra, is sometimes called the e-waste capital of Africa. Agbogbloshie originally took in used electronics, mostly from Europe, for resale in its local market. Similar to China’s turn inward, Agbogbloshie is busy these days processing Africa’s proliferating domestic e-waste. In 2010, residents of Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Liberia, and Nigeria generated between 50 percent and 85 percent of the e-waste in their countries, according to a 2011 report.37 As in Guiyu, used-electronics imports from industrialized countries exacerbate West Africa’s local e-waste problem. The report notes that up to 30 percent of West Africa e-waste originates from residents using “used [electronics] of unclear quality”38 imported primarily from Europe, but also from Asia and North America.

Looking for metals to reclaim in Agbogbloshie, Ghana (Fairphone)

International treaties exist that forbid the trade of nonfunctioning e-waste. However, the United States is not a party to them. The Basel Convention is a U.N.-sponsored treaty that regulates the export and import of hazardous waste. It became effective in 1992 and has been ratified by 181 countries that pledge not to export hazardous waste unless the receiving country gives prior written consent and the trade is done in an “environmentally sound”39 manner. The United States signed the Basel Convention in 1990, but never ratified or implemented the treaty, so it is not bound by its terms.

In 1994, when it became clear that the Basel Convention wasn’t enough to stop global e-waste dumping, the countries that ratified the treaty introduced an amendment known as the Ban Amendment. The Ban Amendment specifically prohibits the export of hazardous waste from wealthy countries that are part of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) to non-OECD countries. So far, 78 countries, including the European Union, have ratified the amendment. It will be entered into force if thirteen more countries that were party to the Basel Convention in 1994 sign it.

The United States has not signed or ratified the Ban Amendment. Environmental activists say corporate interests prevent the government from taking action. “There tends to be a kneejerk response that if something restricts exports, it’s antibusiness and harms our economy,” says Barbara Kyle, the national coordinator of the Electronics TakeBack Coalition (ETBC), a San Francisco–based coalition of environmental and consumer organizations that promotes responsible recycling of consumer electronics. E-waste may still leak from European countries to places such as Agbogbloshie despite the Ban Amendment, but as Kyle says, “They’re definitely [doing] better than us [at tackling e-waste exports].”

Currently the United States has only one e-waste export rule, and it relates to cathode ray tubes, the glass vacuum tubes that were used in TV sets and computer monitors before flat screens became popular. Cathode ray tubes each contain several pounds of lead, so companies are supposed to notify the EPA and get permission from the receiving country before exporting them for recycling. In July 2013, a federal court fined a Colorado-based company called Executive Recycling $4.5 million and sentenced its CEO to two and a half years in prison for smuggling more than 100,000 used cathode ray tubes to China and other countries. The ruling, which was the first U.S. conviction for an e-waste exportation crime, scared dishonest recyclers, but experts say most e-waste infractions continue to go unnoticed and unpunished. “Electronics recycling is almost entirely unregulated as an industry [in the United States],” says Kyle.

Environmental advocates hope a bill called the Responsible Electronics Recycling Act (RERA) will bolster U.S. e-waste export regulations. RERA aims to create a new category of e-waste called “restricted electronic waste.” Gadgets that contain toxic materials would be considered restricted electronic waste and banned from export to non-OECD or non-EU nations. Violators would incur criminal penalties. Kyle says the bill was designed to be consistent with the Basel Convention and the Ban Amendment. “Similar aims would be accomplished, just through legislation and not a treaty,” she says.

RERA was first introduced in Congress in 2011, but the bill never moved out of the committee stage, despite bipartisan support. In July 2013, RERA was reintroduced with the backing of a large coalition of electronics recyclers that have U.S. operations. The group, which is called the Coalition for American Electronics Recycling, has more than 125 members, including the world’s biggest electronic recycler, Britain’s Sims Recycling Solutions, and North America’s biggest recycler, the Houston-based Waste Management. The coalition is championing RERA as a job creator. It estimates RERA will foster up to 42,000 jobs in the United States by mandating that more e-waste be recycled domestically. Apple and Samsung are also listed on the bill as official supporters.

Activists are confident RERA will pass now that it has strong business backing. But another big industry association, the Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries (ISRI), opposes the bill and has lobbied against it in the past. In July 2013, ISRI criticized RERA for “identifying environmental risk based simply on geographic location rather than responsible operating practices,” an approach it called “outdated.”40 ISRI also said the bill violates U.S. trade obligations by discriminating against non-OECD countries. But Kyle says some rules are necessary to prevent the worst forms of e-waste from being sent to countries that have poor records of managing toxic materials. “RERA does put restrictions on what form of stuff can get exported, but it is not anti-export,” she insists.

SMARTPHONE TRADE-INS

One way to counteract e-waste is to reuse gadgets and prevent them from becoming e-waste in the first place. Smartphones are uniquely qualified for reuse, since they are more likely than other gadgets to be refurbished and resold due to consumer demand. A smartphone can have several lives and owners without requiring major changes to its hardware or software. Usually it just needs to be reset to its default software to clear personal data and to be outfitted with a new SIM card, so it can operate with a different phone number. In terms of environmental impact, reuse is preferable to recycling, because it is a more efficient use of resources.

The challenge with smartphone reuse is that people tend to hang on to their old phones. People either don’t realize that the phones have monetary value, are concerned about erasing personal information from them, or want to keep them as backup devices in case their new phones break or malfunction. Kyle calls this the “dead cellphone drawer” problem. That’s the drawer where people store their most recent phone, or maybe even every cellphone they’ve ever owned.

A number of companies are trying to pry open these drawers by offering consumers money to trade in their old smartphones. Many of these companies operate online. They solicit used smartphones via their websites, ask consumers to mail in their phones, and send payment via mail or an online service such as PayPal.

Gazelle is the largest of these online trade-in sites. The Boston-based company buys, resells, and recycles used smartphones, tablets, iPods, and Mac and Macbook computers, with smartphones making up the majority of its transactions. Gazelle’s business illustrates why smartphones have strong reuse potential. For logistical reasons, Gazelle purchases devices only from consumers located in the United States, but the smartphones it buys go on to have second lives all over the world. After wiping the phones’ software to remove personal data, Gazelle lists phones that are in demand and in good condition on eBay and Amazon. Gazelle CEO Israel Ganot says 30 percent of Gazelle’s inventory is resold this way. The remaining 70 percent goes to around 30 wholesalers for resale, mostly in Africa, China, India, and Latin America.

Consumers in developing economies are eager buyers of used smartphones. Carriers in those regions usually don’t subsidize phones, so new smartphones can cost as much as $800 to $1,000 when import taxes or other tariffs are added. These consumers may also have limited access to smartphones because of regional supply shortages or distribution obstacles. “If you live in the middle of China, there are no Apple stores,” notes Ganot.

Ganot says he can always find buyers for Gazelle’s smartphones. What he needs are more phones to sell to them. The smartphone subsidy system is one factor preventing more Americans from trading in their phones. Ganot says Americans don’t recognize how valuable their smartphones are because we pay relatively little for them. “Most of us, when we buy a subsidized phone from a carrier, will pay $200,” he explains. “So, consumers think [their phones] are worth nothing after using them for a few years, but actually they can get as much as what they paid originally [if they trade them in].”

Companies like Gazelle were early to spot smartphones’ resale value. Most carriers and phone makers took longer to launch trade-in programs that target resalable devices and offer people a financial reward. Initially smartphone companies offered only takeback programs that recycled people’s old, beat-up phones (and offered no compensation). Some takeback initiatives benefited charities, such as Verizon’s HopeLine program, which has donated used phones to organizations against domestic violence since 2001. Others were state-mandated. California, Illinois, Maine, and New York have recycling acts that require companies selling cellphones in their states to take back used phones and recycle them. In other states and countries, smartphone companies operate takeback initiatives on a voluntary basis.

Today almost all of the major smartphone companies offer trade-in programs, usually managed by outside logistics providers. Trade-in and takeback programs are the main ways smartphone companies burnish their environmental credentials and counteract the e-waste they help create. Publications such as Newsweek regularly cite Sprint as a “green” company, due to its extensive trade-in and takeback efforts, which Sprint says have resulted in the collection of more than 50 million wireless devices. Sprint’s site tells visitors they can “make a difference today” by trading in their phones and keeping them out of landfills.41

Sprint isn’t just interested in being green. Trade-in programs are another way for carriers to expand their margins—in this case, by affordably acquiring phones that can be refurbished and resold to consumers, either in the United States or abroad or deployed as replacement handsets in carriers’ phone-insurance programs. Carriers make more profit from these transactions than they do selling new subsidized smartphones, because there is no subsidy involved in a used-phone trade-in. As the market researcher Pyramid Research published in a recent report, “The increasing weight of smartphone subsidies on mobile operators’ profitability and the growing demand for used smartphones in emerging markets create fertile land for buyback and trade-in programs.”42

Like the carriers, smartphone makers buy back their old phones for several reasons. They too want to encourage phone upgrades by giving consumers funds to buy new phones. Phone makers may also want to resell these used phones in developing economies, harvest the phones for replacement parts for repairs, or just keep as many phones as possible off the secondhand market, so consumers will have to buy new phones.

Certified Recyclers

Trade-in programs might seem ideal solutions to the smartphone e-waste problem but collecting phones is only half the battle. If trade-in programs don’t repair, resell, and recycle the phones they receive responsibly, they will intensify the e-waste problem rather than help alleviate it. As Kyle puts it, “There are two very different [e-waste] issues: how hard a company tries to collect stuff, and then what it does with it.” The latter question is particularly pertinent for recycling smartphones. Takeback programs and charitable recycling drives are likely to net smartphones in poor condition, and even trade-in programs can attract plenty of junk. Before Gazelle streamlined its business in 2012, it accepted 22 different types of gadgets and had to send 10 percent of its inventory to recycling, according to Ganot.

Fortunately, even broken, unusable smartphones have considerable value. They are more lucrative for recyclers than other forms of e-waste because they have a relatively large amount of precious metals for their small size. Their circuit boards may contain gold, palladium, platinum, and silver, as well as copper and nickel, which are not precious metals but do have monetary value. The EPA has calculated that recycling a million cellphones can recover 35,274 pounds of copper, 772 pounds of silver, 75 pounds of gold, and 33 pounds of palladium. Recycling companies will pay more than $15 per pound for smartphone circuit boards so they can reclaim these metals, says Joel Urano, president and CEO of Capstone Wireless, a Dallas-based cellphone repair, refurbishing, and resale company.

Environmentalists know recyclers are motivated to collect smartphones, but they worry that unscrupulous recyclers will cherry-pick valuable parts, such as circuit boards, out of their scrap and dump the rest in the trash or export it to places like Guiyu and Agbogbloshie. Activists say consumers in search of ethical recyclers should look for certification credentials, for instance, from Responsible Recycling (R2) or e-Stewards.

Of the two, e-Stewards has stricter ethical and moral requirements. Both programs oblige companies to maximize the reuse and resale of the e-scrap material they receive, to safeguard their workers’ health and safety, and to wipe data from phones they receive to protect consumers’ privacy and security. But e-Stewards is the only standard that prohibits the export of hazardous e-waste to developing countries. R2-certified companies can send used electronics internationally as long as the receiving country legally accepts such shipments and the company “demonstrate[s] compliance of each shipment with the applicable export and import laws.”43

The two standards also diverge on the matter of using prison labor to process e-waste—a practice that appeals to some recyclers because of its low cost. To employ prison labor, recyclers hire UNICOR, a government-owned corporation established in the 1930s to give inmates job training. UNICOR started using prisoners to recycle computers and other gadgets in Florida in 1994 and expanded its operations to prisons in several other states in 1997. It says it teaches inmates marketable skills, but early tasks included smashing TVs and computer monitors with hammers—and without protective equipment. By the early 2000s, workers were concerned about respiratory problems and rashes. Prompted by lobbying on their behalf, the Justice Department’s Office of the Inspector General investigated UNICOR recycling facilities across the country. The resulting report, published in 2010, said UNICOR exposed workers to 31 metals, including cadmium and lead, and “concealed warnings”44 about those hazards. UNICOR started making improvements in 2003 and by 2009 its e-waste operations were being operated safely “with limited exceptions.”45 Now UNICOR is R2-certified and R2 companies can hire UNICOR to recycle e-waste, but the e-Stewards standard expressly prohibits the use of prison labor, due to ongoing concerns about health risks for prisoners and data-security risks for consumers and companies.

Smartphone recycling is a multistep process that involves some human labor and a lot of automation. Companies send smartphones to e-Stewards and R2 recycler ECS Refining in huge boxes that can hold 10,000 units. Often these phones are relatively intact but damaged beyond repair. ECS employees inspect the phones and remove their batteries, which must be handled separately, because they can cause fires or small explosions if punctured. After this triage is complete, shredder and grinder machines chop the rest of the phone into two-and-a-half-inch-long pieces. Those are spit out onto a conveyor belt, where magnets isolate glass and plastic from metal, and then separate different types of metals into piles.

The entire process, from triage to the sorting of shredded material, takes only a few hours, according to Jeff Bell, the general manager at ECS’s Mesquite, Texas, facility. Smartphones take a little longer to triage than basic phones, because their casings are harder to open and their batteries are often concealed deep within the phone. “The iPhone is a sealed unit,” says Bell. “You have to touch smartphones a little more to get the batteries out.” Once these flammable items have been removed, Bell says, his plant, which is one of three processing centers ECS operates in Texas and California, can shred 15 to 25 tons of smartphone material per hour. ECS sends the shredded material to refiners in Belgium and Canada that smelt it to recover precious metals. Those companies pay ECS based on the weight of the precious metals they are able to reclaim.

Under e-Stewards rules, ECS can export e-scrap, because it is not sending junk but rather raw materials, which other companies use to create new products. “There are no residuals when we’re done [processing a smartphone],” says Bell. “The next people take [what we produce] and turn it into a new form.” Recovered aluminum and steel are often sold at metals markets. Plastic smartphone casings have less value, but they can be sent to plastics processors that grind them into pellets, which manufacturers then buy to make new goods. Used smartphone batteries can be resold, too. Bell says various companies will buy batteries that still hold 85 percent to 90 percent of their charge and use them as replacement parts. Dead batteries go to recyclers that specialize in smelting batteries for metals, including lithium and nickel. ECS even buys smartphone chargers and charging cords, because they contain copper and steel, which can be reclaimed after shredding and chopping. Glass is the one smartphone material that is difficult to resell, because it needs to be pristine to retain its value. Says Bell, “We can resell glass if it’s usable, but typically we’re recycling it [at a glass recycler].”

ECS essentially functions as a one-stop shop for e-waste processing. Bell says approximately 10 companies in the United States can handle the same breadth and volume of material under one roof. The number of e-Stewards recyclers that can do the same is much smaller. The reason is simple: recyclers must invest considerable time and expense to get certified and stay certified. Bell’s plant has sophisticated environmental controls, including systems that monitor air quality throughout the facility and collect the dust generated by the grinding machines. ECS also provides hazardous-material respirators and uniforms for its employees and launders their uniforms to ensure they are kept clean. The company even tests its employees’ blood to certify that they are not being exposed to high lead levels from the circuit board grinding process.

There’s also the matter of record keeping: e-Stewards regulations emphasize transparency and accountability in business dealings. ECS has to track the materials it buys and sells, through inventories and shipping manifests, and share those records with its e-Stewards customers. All e-Stewards companies pay for a third-party auditing firm to check their compliance with the program’s rules and they also send Basel Action Network (BAN), the nonprofit that oversees e-Stewards, an annual licensing and marketing fee that ranges from $500 to $90,000, depending on their revenues. Noncertified recyclers have lower operational expenses and can afford to pay more for used materials. That gives companies that don’t care about rigorous recycling ethics a big incentive not to select a certified recycler. Capstone CEO Urano says prospective clients have told him, “ ‘These [other] guys are paying more and will recycle everything.’ . . . Those companies don’t ask [those recyclers] if they’re R2 or e-Stewards certified.”

A few large retailers, such as Best Buy and Staples, use certified recyclers for their takeback and trade-in programs. Smartphone companies have varied policies. Apple utilizes Sims Recycling Solutions, which is e-Stewards and R2 certified, for its iPhone recycling program. Samsung and LG have been e-Stewards “enterprise” members since 2010 and 2011, respectively, which means they’ve agreed to use e-Stewards recyclers when possible for their recycling efforts. In 2013, LG upped its commitment and now sends all of its U.S. e-waste to e-Stewards recyclers, leading BAN to call it “the most responsible electronics company operating in the United States when it comes to managing e-waste.”46 Sprint and Verizon use eRecycling Corps, an R2-certified recycler, for their device buyback and trade-in programs and T-Mobile says its recyclers are either R2- or e-Stewards-certified. Other smartphone companies say they responsibly recycle any e-waste they acquire, but they don’t publicize that they use certified recyclers, so it’s unclear how rigorous their standards are.

E-waste Solutions