Chapter One

The Rocky Mountain News, one of Denver’s local newspapers, forecast on January 1, 1925, that the city would begin the year buried under an old-fashioned blizzard.

The actuality was more of a gentle blanketing of snow. A cross between the light flurries that swirl back into the air on gusts of wind, and the heavy drifts that ice into mounds on utility and telephone wires, weighing the wires down so low that they sometimes snap and fall to the ground. A snow that’s back-breaking to shovel and makes streets nearly impossible to drive down, but that is great for rolling into jolly snowmen or compressing into deadly snowballs.

It was the kind of snowfall that inspired old-timers to swap stories about the times, seventy or eighty years back, when the territory that is now Denver was home to buffalo herds and populated by camps of Arapaho and Cheyenne Indians, … when Denver was only populated with makeshift trading posts and mining camps that had sprung up between the confluence of Clear Creek and South Platte River.

“Yeah, and how about all them gosh-durn buildings in every direction. Banks, hospitals, schools, churches, libraries, hotels — even one built by some colored fella name of Ford — and cinema palaces,” one of the grizzled old men would say.

“Yep. And don’t forget the elite dry goods stores and fancy amusement parks, roller coasters, Ferris wheels, and all. But that ain’t the top of it. Now, houses and what not, springing up far out as can be,” someone equally as timeworn would add.

“Truth to tell,” yet another old-timer would pipe in. “But it’s them country club bunch of sons and daughters what really got my dander up. They just plain showing off. I mean what’s a body need with thirty rooms in one house? Why they almost need their own brick factory to build one of them monstrosities. And then there’s them blasted automobiles. Instance, last week, some crazy fool driving a long yellow DeSoto just about runned over me.”

“Yep, know what you mean,” the conversation would start all over again, “Denver jest ain’t what it used to be.”

There was one topic, however, even newcomers could join in on—the majesty and beauty of the Rocky Mountains. The snowcapped peaks stretched thirty-miles north to south along the western boundary of Denver, as if created to be a daily reminder of God himself. Wagon trains crossed them to go west, journeys that could take four, five, sometimes six weeks or more … and many just couldn’t make it across the steep passes or out of the deep canyons.

Now, in the two or three generations since the trail and mining days, small towns were nestled throughout the Rockies, while communities along the foothills, such as the little city of Golden, looked out over Denver and the other flatland settlements.

Indeed, it was to the summit of Golden’s Table Mountain that young lovers drove to park and watch the swirl of red, purple, and yellow light ebb from the plains sky as Denver’s street lamps came on.

Margaret Browne only knew of such excursions when she overheard her stepson Kyle and his friends plotting a drive to Golden in a family automobile. Margaret didn’t like Kyle being twenty-five miles from home, especially with the bunch of hooligans he had taken up with lately, and forbid him to go. Lately, however, he disobeyed and went anyway.

It wasn’t that she didn’t trust Kyle, who, after all, at seventeen, was really a young man; it was just that she tried to protect him from his father who always accused Kyle of doing something wrong.

Devin didn’t trust anyone. He wouldn’t even permit Margaret, a grown woman of thirty-four, to learn to drive.

Today, though, was not a time for worrying. Kyle and Devin had gone off on their own, leaving Margaret alone in the house with her mother-in-law Mother Browne and their butler Walter, which meant a rare chance for Margaret to leave the house without having to tell Devin where she was going.

Margaret had to hurry. If Devin came home unexpectedly, he most certainly would make her stay home. And she certainly didn’t want to ask Walter to lie for her, which she had already done several months ago, only to see by the look on his face that it wasn’t something he was comfortable doing. She had to leave now, while Walter had gone to the drugstore for Mother Browne’s new prescriptions. She didn’t want to leave her mother-in-law alone, but she had little choice.

Margaret went to the hall closet and took her coat, hat, and ice skates from their hook, and retrieved her sketchbook and pencils from their hiding place in a box marked “Tree Ornaments.”

Thankfully, she’d made sure to put the gloves Kyle had given her for Christmas in one of her coat pockets, so she didn’t have to go back upstairs for anything.

She walked out onto the front porch and looked directly to the mountains. The peaks were hidden by a bank of clouds that also covered the sun, and it had started snowing again. The day was gray and somber. The temperature was three or four degrees below zero.

She put on her gloves, walked down the porch steps to the sidewalk, and began the ten-block hike to the trolley stop on Seventeenth Avenue. She remembered to line her boots with newspaper, insulating her feet against the cold, so her only real worry was not to slip on the seemingly invisible black ice that covered the flagstone sidewalks.

Most homeowners on Grant Street, however, were conscientious and prided themselves on keeping the walks of their affluent neighborhood well-salted.

Margaret had walked only two blocks when a young woman with an infant in her arms passed by going in the opposite direction. The woman’s gloveless hands were turning blue. Frostbite.

Margaret took two more steps, stopped, hesitated an instant, then pulled off her gloves and ran back toward the woman. “Here,” she blurted as she came shoulder-to-shoulder with the woman, and held out her gloves. “Put these on. I’ll hold the baby for you.”

The woman looked at Margaret in disbelief, but handed the bundled infant over. The woman was shivering, but struggled to talk. “I, I, I don’t know what to …”

“Please,” Margaret said, as she pulled the baby’s yellow blanket closer to its face, “there’s no need to say anything. I already know.”

Ten minutes later, three blocks from her trolley stop, Margaret’s hands turned painfully blue. She pushed her hands deeper into her coat pockets and tried to walk faster. She attempted to ignore her numb toes. After all, suffering an afternoon of winter weather was nothing compared to what she stood to gain for the rest of her life.

As Margaret waited for the trolley, she took her hands from her coat pockets and placed them palms down on her stomach. The baby growing in her womb was so helpless. She had to tell Devin soon that she was pregnant. But what if even that didn’t stop him from beating her?

She tried to keep from feeling the pain in her bruised shoulder. She wasn’t going to allow anything to keep her from searching for her daughter.

Devin didn’t know that she’d had a child seventeen years ago or he never would have married her. Somehow, she had to find the courage to tell him that too.

Clang. Clang. The trolley screeched to a stop and Margaret stepped on.

She chose a seat with as few people nearby as possible, and sat down with a deep sigh of relief. She filled the adjoining seat with her ice skates and sketchbook and hoped no one would ask for the seat. Her hands and feet ached as they began to thaw. She realized that the morning was already gone.

Clang. Clang. The trolley bell turned Margaret’s attention to the passing scenery.

Many storefronts along Seventeenth were still decorated for Christmas with candy canes painted on the shops’ windows and pine wreaths hung on their doors. She had the feeling that she wasn’t so much passing through a commerce district, but rather through a lovely alpine village. “Peace on earth, good will to men,” Margaret said softly, truly meaning it.

The seasonal tiding made her think of Gwen, who was Jewish, but had been her best friend since childhood. Now their lives were as opposite as ginger ale and champagne, especially now that Gwen had inherited her parents’ fortune. Yet she and Gwen still loved each other like they were the sisters each had longed for.

Margaret gazed out at the East Denver Ice Cream Parlor and Confectioner, where Gwen had kissed her first gentile boy, and the Rexall Sundry and Drug Store, where Margaret had shoplifted some rouge. She had been so overcome with guilt that she had run straight home and spent an entire six hours on her knees reciting “Hail Mary” and “Our Father” over and over again.

There was also the nameless and wonderfully mysterious antique shop where they’d had the most fun. They seldom purchased anything, but the owner hadn’t seemed to mind. He let them spend hours sorting through the overburdened clothes racks for items to try on, and they found everything from antebellum hoop skirts to Red Cross uniforms to black silk kimonos.

Margaret never would forget when Gwen found the red hoochie-koochie dress with the fringe all around it, put it on, and sashayed around as if she were one of those women on Market Street.

“Pennsylvania,” the trolley conductor sang out. Two riders exited the car at the rear as new riders boarded at the front. The token box chimed with the deposit of each eightcent fare.

One of the new riders, an attractive Negro woman who seemed somehow ageless, walked by the several empty seats at the front of the trolley and made her way to a seat in the rear of the trolley.

Two other new riders, a boy and girl about twelve years old talked excitedly and, like Margaret, had their ice skates with them. They stood in the aisle near her and stomped slush from their galoshes and shook snow from their caps. Margaret turned her face back toward the window to avoid the assault of moisture.

Just as she looked out the window, she saw a car skid across the icy street, crashing into a telephone pole. The radio broadcast she heard that morning came to mind. The announcer warned of downed power lines throughout the city. She tried to visualize what it all must look like.

South Denver and Englewood were mostly residential, but there were also orchards and sanatoriums. Obviously, those repairs would come last.

North to the stockyards and factories of Globeville, and west to the mills and breweries of Golden, many people needed safe roads to get to work, so crews were probably at work in those areas already.

She had never been to the east suburbs and airfields, so couldn’t picture that part of the city. Maybe Devin would take the family on a drive out that way some weekend. Then again, the last time they’d been on a Sunday outing Devin had caused an accident and had had to spend the night in jail for punching out the other driver. If only he would allow her to learn to drive.

Margaret closed her eyes and hoped the gentle hum of the trolley’s motion would quiet her thoughts. It didn’t. Within seconds her mind was aflame again with guilt and dread.

Why had she fooled herself all these years into believing the impossible, into believing that Devin would eventually fall in love with her and no longer compare her to his deceased first wife, believing that she, the daughter of a humble dry goods merchant, would eventually be welcomed into his family’s social circle—Denver’s Sacred 36?

Rather, she had to finally accept that she and Devin would always occupy separate worlds - his, primarily polo fields and country clubs, hers, the working-class neighborhood.

Devin hadn’t even seemed to notice or care that she had

retreated into a life of household duties and church bazaars. Her only saving grace was that she had begun to sketch nature scenes, and had found that she had a talent for it. She’d even secretly sold a few of her sketches to a local curio shop that reproduced the scenes on postal cards.

“Clarkson,” the conductor announced. This time, however, Margaret was too lost in thought to notice those who came or went. Instead, she was replaying scenes of how Devin’s behavior had drastically changed during the last year. Before, he’d been merely inconsiderate; but, during the last months he’d become brutish.

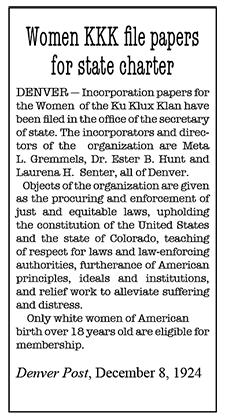

It was as if something about this newest scheme of his—some kind of membership campaign for a secret organization—had unleashed his most vile nature. He had become more than a little cruel and violent.

There had to be more explanation than the fact that her father had fallen behind on his monthly deposits into Devin’s bank account with these deposits. The Brownes had managed for so many years to keep up appearances, and, before Father Browne died, to pay off his gambling debts. But what could it be?

Margaret’s question led to thoughts of her father. She loved Angus deeply, but wished at least once a day that he hadn’t insisted upon her marrying Devin. Even after all these years, she could still hear her father’s argument.

“Listen lassie, this is a mighty good match. It’s not everyone that can marry into a first-class family like the Brownes. Trust me, there’s a long line of other girls who wish they were in your very place.”

Margaret wondered if this sacrificial social climbing existed among other races and cultures, or was it simply the white race’s shortcoming? She found herself back worrying about Devin, hoping that he hadn’t mortgaged their house, which his grandfather had built during the Gold Rush.

She felt a flutter in her womb and glanced back out the window. How ironic. After years of disappointment and heartache, and shedding her final tears for the child that she was apparently never going to have, she was at last pregnant. Three months.

Still, she couldn’t shake the sense of mourning, only, for which child? The one she’d raised? The one soon to be born into a loveless marriage? Or, the one who had been …

No. She had to stop doing this to herself.

She saw a bony, filthy mutt scratching earnestly into a mound of hardened, dirty snow. An ache clenched her chest.

“Don’t worry, you miserable thing,” Margaret whispered, even though the dog couldn’t possibly hear her, “spring isn’t so far off.”

Clang. Clang. The trolley continued east down Seventeenth, past Capitol Hill toward City Park. If only she could make it that far before her breakfast retched back up.

She closed her eyes for a brief moment, but was unsettled by what she saw when she reopened them — Dr. Woods’ office.

The sting of the past pain flooded her mind. No matter how earnestly she attempted to force the memory away, every detail of Dr. Woods’ dingy back room was as clear to her as the day her father had taken her there.

She remembered the smell of antiseptic that overwhelmed her, wondering if she was somehow about to be strapped to that same narrow bed.

Equally unbearable was her recollection of the nurse, a squat, heavy-set blonde with wire-rimmed glasses that spoke with an accent of some kind—Hungarian or maybe Polish—who had taken her wailing baby into the next room never to be seen.

“Not good. Not good,” the woman had said when Margaret begged to hold her newborn baby. “She have new mama now.”

The nurse had quieted Margaret’s pleas by pressing a cloth full of chloroform to her face, but as she drifted off to sleep, Margaret clung to the memory of the word “she” as if it were a satchel full of gold nuggets.

It was morning when Margaret awoke to a new nurse, who claimed to know nothing about any such baby. Her only role, the new nurse had declared, was to have Margaret dressed and ready to go home when her father drove up to the office’s rear entrance to pick her up.

Margaret could still see her father’s expressionless face when he leaned across the seat of his Model-T to push open the car’s passenger door. He sped off as soon as she was inside the car and said nothing to her during the ride home.

Like everything else her father had refused to acknowledge—his past, Margaret’s mother, the father of Margaret’s baby—they didn’t discuss the baby either. In fact, as soon as they had arrived home, and for all the months and years afterward, she and her father went on with life as if nothing out of the ordinary had happened; not that Margaret didn’t try every once in awhile to bring up the subject. Her father simply ignored her questions or left the room.

Exhausted by the memory, Margaret turned her attention to her fellow trolley riders.

A redheaded man of about twenty was sitting across the aisle. She decided that her father might have looked very much the same in his own young adulthood, forty-five or fifty years ago. But that was only a guess, because she didn’t know her father’s age nor had she seen a photograph of him as a young man or boy. He probably hadn’t allowed any to be taken. She wasn’t absolutely sure that his real name was Angus O’Shea.

Again, Margaret wondered if the forbidden topic of his youth had anything to do with the scar that extended down his face.

She also thought of her mother, who had abandoned the family when Margaret was only six. She hated thinking of her mother, who had never so much as written to explain. If it hadn’t been for two old busybodies she’d overheard gossiping at a Holy Cross bake sale, she wouldn’t have known that her mother had returned to her homeland in Norway. It had been the first time she felt happy that she looked most like her father. Before then, she had cursed her unruly red hair and the stubborn streak she had inherited from him as well.

“Humboldt.” Again, the trolley braked and its front and rear doors flung open. A swirl of snow flakes swept in on a gush of cold air and reminded Margaret of her destination.

Her spirits lifted. She slipped a hand underneath her coat and tenderly caressed her stomach. She realized soon she would have to stop wearing a corset.

With her free hand she pulled a rosary from her coat pocket and entwined the long string of glass beads around her fingers. “Hail Mary, full of grace,” she recited. “The Lord is with thee. Blessed art thou among women; blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus. Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners, now and at the hour of our death. Amen. Hail Mary, full of grace. The Lord is with thee.”

Once more, her thoughts drifted to the early morning when Devin stumbled in, inebriated and stinking of bootleg whiskey and cheap cologne. He had threatened her with his fist at finding his supper cold.

She had to face the truth. Devin was becoming increasingly dangerous to her and the baby.

The trolley’s gentle rocking came to a sudden stop and jolted her. She reached out to the seat ahead to brace herself. She looked at her hand and for a moment was alarmed.

Her wedding ring was missing, but she suddenly remembered her visit to the pawn shop. For the one hundred and twenty-five dollars she had received for her ring, she had settled the coal and grocery bills. She also attempted to pay Walter his monthly wages, but he had refused to accept. Instead, she used that money to pay Mother Browne’s doctor and have the leaky roof repaired.

She put her palm to the window and rubbed in circles until the heat of her hand defrosted the ice crystals. More shops came into view.

Clang. Clang. Happily, Weinstein’s Bakery was ahead. Margaret smiled because the bakery had been one of Gwen and Margaret’s favorite places during their high school years.

Mr. and Mrs. Weinstein were the nicest people Margaret ever met, and their son Isaac—before he’d gone to the war and been lost at sea—was so funny that he should have been in Vaudeville.

When Gwen’s parents were out of town, and left her with extra money, the girls went to the Weinstein’s bakery sometimes two or three times a week.

Still, no matter how often they went, Mrs. Weinstein always added an extra cookie or cupcake to both their bags that neither girl had paid for.

Even if they discovered the bonus after arriving home, Margaret always insisted that she and Gwen rush back to pay the additional nickel or dime.

As soon as Mrs. Weinstein saw the girls coming back in the door, she’d quickly send Mr. Weinstein to the basement storeroom for some suddenly needed item. And the outcome never differed.

The girls, out of breath from running, would hold out the money they owed, and Mrs. Weinstein would fold her arms, hunch her shoulders, and refuse to take it.

“So, I’m not so good with numbers,” she would say, then add, “so, the world should end?”

Almost simultaneously, Mr. Weinstein would reappear, having filled his wife’s request, and Mrs. Weinstein would shoo the girls on their way. Margaret smiled at the memory and eagerly awaited the cheery storefront coming into view.

In its place, however, stood a small boarded-up building with licks of black scarring its outer wall.

What in God’s name? Margaret gasped. Where was the bakery? She squeezed her eyes closed and swallowed hard. She couldn’t bear to look. Her thoughts became a screaming blur as the trolley continued past the burned structure.

It’s not possible she thought. That nosey butcher, with his foolish blather, couldn’t have been right. All he told were fibs. Besides, Devin had promised her that the Klan would leave the bakery alone.

“Gaylord,” the conductor called. The next stop was Margaret’s, but she was barely able to breathe. For the baby’s sake, she had to remain calm. She took a few deep breaths, forcing the air in her lungs back out.

A grizzled old man, wearing a tattered, dirty Chesterfield coat that must have once been of fine quality, was standing in the aisle, staring at her.

“Hey Duchess, ya mind?” the man asked.

His gravelly voice broke into her thoughts. “I’m sorry … what?” she asked, still hyperventilating.

“Ya mind if I sit?” he said, looking at her ice skates and sketchbook in the adjoining seat.

Margaret quickly looked and saw that all the other seats in the trolley were taken. “No, not at all,” she said, thankful to be distracted. “We’re practically at my stop anyway. In fact,” she added as she gathered her belongings, “why don’t we just exchange places?”

She scooted out of her seat and stood, expecting the man to sit, but he remained standing. He was holding out a grubby palm in which rested a shiny silver dollar. “Thanks, Duchess,” he said, “that’s right decent of ya. I’d like ya to have this … for ya troubles.”

“Oh, no, I couldn’t,” Margaret said, admiring the coin.

“It’s awfully handsome though.”

“Look Duchess, ya’d be doin’ me a favor,” the man said, then took her hand and emptied the coin into it.

“Thank you,” Margaret said, for some reason joyfully relenting. Suddenly, she recognized the man. It was Silver Dollar Joe, one of Denver’s last surviving ‘59ers, and once the most renowned tycoon west of the Mississippi.

Now he was an impoverished old man and lived under the viaducts, but would appear in various places around the city giving away silver dollars.

Margaret watched him take her vacant seat, then turn his face toward the window. She was glad that Gwen would be meeting her at the park so that she could tell her about all of this.

“Elizabeth,” the conductor called, and clanged the bell as he brought the trolley to the first stop along City Park.

Margaret took another deep breath. Now was no time to weaken. If the nightmare of her daughter being taken from her was ever going to become a dream come true of being reunited, only she could make it so.

The trolley’s rear door opened, and Margaret stepped into the crisp winter day. The sky was now cloudless and achingly blue. A few of the houses bordering the park had white smoke curling from their chimneys. The noon sun reflected blindingly bright off the snow. A perfect day.

Margaret took the closest path into the park and turned her thoughts to her child, who actually would now be a beautiful young woman of seventeen.