TWO

The Social Self

For those communities, which included the greatest number of the most sympathetic members, would flourish best, and rear the greatest number of offspring.

—Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man

During the first few minutes of her first session Clara complained, “My parents never really wanted me.” She described how both parents were highly successful professionals who had little if any time for her. With grandparents far away and no siblings, she had no sense of family. To please her parents she became one of the top students in all of her classes through graduate school, yet that did not garner their attention. She complained that she felt empty, adding, “There’s always been this feeling that there is something missing in me.”

As an adult she attempted to establish a close intimate relationships, but her brief romantic encounters ended with both her and her potential partner acknowledging the existence of an emptiness between them. She asked me, “Where does this emptiness come from?” With her aging parents needing her help to move into an assisted living environment, even the thought of spending time with them was annoying. In response to this expectation, she hired a social worker not only to deal with the move but also to talk to them about their “incessant complaining about losing their independence.”

She looked at me with astonishment and asked, “What am I supposed to do with their feelings?” Almost in the same breath she noted that she asked the same question to the man whom she dated for the third and last time. “All he could say was, ‘If you don’t know, I can’t help you’!”

Humans are fundamentally a social species. We thrive within positive relationships and suffer without them. Clara complained that she felt that there was something missing in her. The implicit emptiness she felt with others mirrored her underdeveloped sense of self. Though she managed to excel through graduate school with a well-developed executive network, her salience network was impoverished and used her default-mode network to bemoan relationships gone sour.

How malleable are our brains to fill the emptiness that she described with implicit memories of insecurity? Are there circuits in the brain that would enable her to develop the capacity for secure relationships and even intimacy? If so, how might psychotherapy promote this capacity? This chapter answers these questions. It is useful to begin by exploring how early experiences shape an infant’s brain.

NURTURED NATURE

The brain of infants has considerable redundancies and many more neurons than that of the obstetricians who deliver them. There is a significant degree of extra undifferentiated potential that permits them to adapt to their unique family, community, and culture. The infant’s brain is also far more malleable than an adult’s. Of all other species, humans spend the longest time in the hands and supervision of caregivers. Our brain is wired by experience in a social context, and the range of possible social experiences is vast.

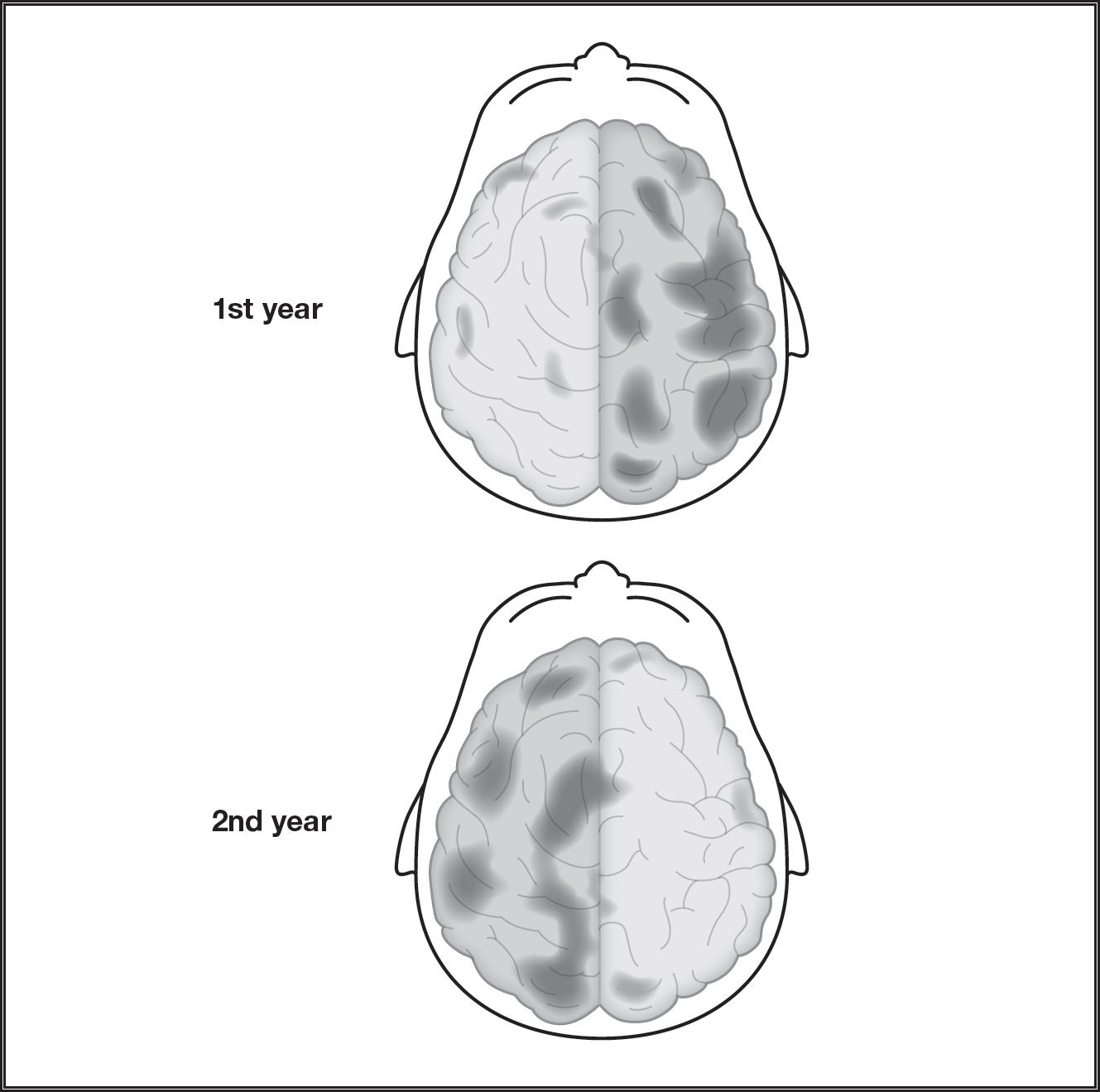

During the first year of life the right hemisphere, relative to the left, tends to be more active (Chiron et al., 1997). The right hemisphere is more adept at picking up the nonverbal emotional nuances of communication so dominant in infant-parent communication. Early development builds implicit-emotional memory of whether or not approaching people offer comfort and safety. For Clara avoidant attachment became her implicit memory system and mode of social interaction. As she grew older the socially sanctioned reference points for intimate relationships collided with her discomfort and lack of intimacy-building skills.

Figure 2.1: The relative dominance of each hemisphere as a child develops. During the first year of life, for example, there is relatively more activity in the right hemisphere followed by the second year with more activity in the left hemisphere.

SOCIAL BRAIN NETWORKS

Though underdeveloped, Clara’s social brain circuits needed to be primed. Though there is no actual “social brain,” some brain circuits are associated with social interactions. Psychotherapy is the interpersonal sculpting that integrates these circuits (Cozolino, 2017), which include the orbital frontal cortex, insula, cingulate cortex, and a few socially sensitive types of neurons. The anterior insula and anterior cingulate contain a unique type of neuron, known for its spindly shape, unique size, and highly connected quality, called the spindle cell.

Social Brain Components

- Orbital frontal cortex

- Amygdala

- Insula

- Cingulate

- Temporal parietal junction

- Mirror neurons

- Spindle cells

- Facial expression modules

Highly social mammals who have been observed displaying empathy-like behavior, such as whales, elephants, and great apes, also have well-developed anterior cingulate and anterior insula (parts of the salience network), and spindle cells within those structures (Allman et al., 2011). At birth humans have approximately 28,000 spindle cells, growing to 184,000 by age four and 193,000 by adulthood. By comparison an adult ape has 7,000.

Spindle cells are rich with serotonin circuitry, intimately connected to mood, social ties, expectation, and reward. They provide a means to grasp an intuitive sense of the emotions of another person, enabling us to make snap, intuitive judgments that are fused with emotion and social sensitivity. While people like Clara need to learn to kindle their activity, spindle cells are vulnerable to abuse and neglect, and they may be impaired in neurodevelopmental disorders (Allman, Watson, Tetreault, & Hakeem, 2005). We can hypothesize that therapists routinely cultivate spindle cell activity to hone alliance-building skills and to detect the emotional nuances of their clients.

So-called mirror neurons were initially discovered in macaque monkeys when they fired after the monkey observed the movement of another individual (Rizzolati & Arbib, 1998). For example, when an individual observes another move an arm but does not do so himself, he fires neurons as if he is moving his own arm. It is believed that mirror neurons were useful during evolution to predict goal-directed behaviors of other individuals. They may have provided an adaptive advantage to predict how to stay safe from potential danger if an observed individual means harm.

Mirror neurons may be found in various areas of the prefrontal cortex, posterior parietal lobe, superior temporal sulcus, insula, and cingulate cortex, which are all associated with social skills. Though they are quite controversial, people have speculated that mirror neurons provide the capacity to experience empathy (Iacoboni, 2004). Others are not convinced that they represent a specific type of neuron. They may be related to motor neurons that are co-opted into firing after observing ourselves move and then later observing another individual make the same movement (Hickcok, 2014). However mirror neurons are understood in the years to come, they and other socially responsive components of the salience network facilitate emotional attunement and empathy. Though Claire had not yet developed these skills, she would cultivate them.

CULTIVATING EMPATHY

The capacity to emphasize with another person is a foundational social skill. As psychotherapy is fundamentally built on social skills, it involves the capacity of the therapist and client to coactivate parts of their brains that bring them closer to a shared understanding. Together these social brain circuits represent the means through which empathy is given and felt.

The area of the brain associated with physical pain overlaps social pain (Lieberman, 2013). Empathy is associated with activity in both the anterior insula and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) (Craig, 2015). Both of these areas are associated with the anticipation of pain, emotional reactions to pain, and understanding the feelings of others (Singer et al., 2004).

While the ACC and insula become active when we experience pain and when we empathetically witness pain in another person, the somatosensory cortex gets activated when we directly experience pain. The density of oxytocin receptors in the ACC is associated with the degree of empathy.

The salience network, which includes the insula, especially on the right side, promotes gut or intuitive feelings about another person. Together with the ACC, the anterior insula provides the capacity for empathy, which comprises the awareness of our own bodily state. In other words, feedback loops from our body are intertwined with feelings about another person.

People like Clara are likely undeveloped in these areas or have actively inhibited these abilities. As a result, they possess less social sensitivity, blunted empathy, and less awareness of their own feelings and bodily states. At the beginning of therapy Clara seemed ill aware of her own body states. In the extreme, those with severe abuse may also exhibit lower heart rate, arousal, and amygdala activity (Vogt & Sikes, 2009).

It was initially difficult for Clara to develop empathy for her aging parents. An opportunity presented itself during one session, when she was suffering from pain from a strained back and began to express concern for her parents. Through the overlapping neural networks between her physical pain and social pain we were able to bridge discussing her thoughts and feelings about cultivating more empathy for her parents.

Feeling rejected during childhood is the antithesis of empathy. Bullying, one type of social pain, has received considerable attention in the media due to a number of widely publicized adolescent suicides. The core of the emotional social brain, the amygdala and anterior cingulate, is activated by verbal abuse and ridicule and deactivated by social support (Coan, Schaefer, & Davidson, 2006; Teicher, Samson, Polcari, & McGreenery, 2006). Social support can coregulate a child’s emotions to promote less amygdala activation and more prefrontal activation (Tottenham, 2014). Buffering social stress with support increases amygdala and prefrontal cortex connectivity to promote secure attachment and reduce anxiety.

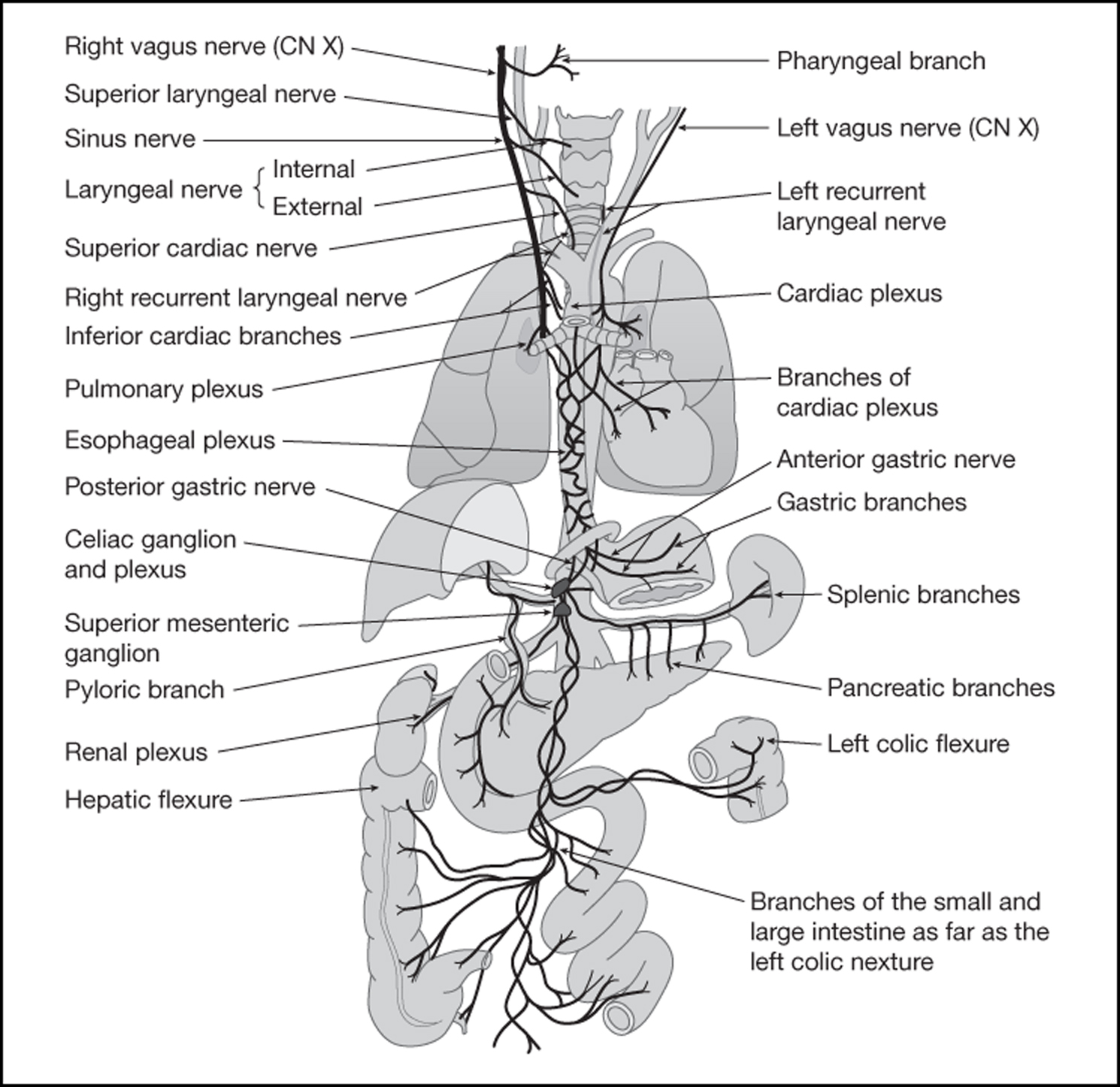

THE VAGAL BRAKE

Through primate evolution, the emergence of the systems of the vagus nerve made possible more sophisticated social engagement skills that combined the ability to regulate affect while simultaneously negotiating the subtle nuances of communication. The myelinated vagus nerve system forms the key part of the parasympathetic nervous system. The vagus (meaning wanderer) enervates many of the organs in the thoracic cavity, as well as the muscles in the lower part of the face and vocal cords. The polyvagal system has also been referred to as the social engagement system because people with a well-functioning vagus possess the capacity to regulate their heartbeat down while expressing emotions without defensiveness (Porges, 2011). To facilitate social engagement, the upper vagal system connects with the smile muscles, the inner ear, and the vocal apparatus used in prosody (Porges, 2011).

Social competence necessitates putting the brakes on a rapid heart rate and masking a frightened or angry facial expression when engaging in potentially tense communication. However, people who have endured adverse childhood experiences tend to have an undeveloped vagus system and are more apt to overreact or remain hypervigilant in response to socially stressful situations. The ability to stay calm while engaging others was not a skill Clara’s parents taught and so represented a goal in therapy.

The vagal brake, with its social engagement system, and affect regulation are interdependent capacities. Together, affect regulation and positive relationships represent two related aspects of mental health. What happens if a child is exposed to no social engagement? This can happen with maternal depression.

Figure 2.2: The vagus nerve system and its connections to the organs in the thorastic cavity.

The Psychoneuroimmunology of Social Support

- Decreased cardiovascular reactivity (Lepore et al., 1997)

- Decreased blood pressure (Spitzer et al., 1992)

- Decreased cortisol levels (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 1984)

- Decreased vulnerability to catching a cold (Cohen et al., 1997)

- Decreased anxiety (Coan, Schaefer, H. S., & Davidson, R. J. (2006)

- Increased natural killer cells (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 1984)

- Slower cognitive decline (Bassuk et al., 1999)

- Improved sleep (Cohen, 2004)

- Lessened depression (Russell & Cutrona, 1991)

THE EFFECTS OF MATERNAL DEPRESSION

Mary, a thirty-two-year-old accountant, was first seen by a psychiatrist in our department for postpartum depression and immediately put on a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. During a team meeting I expressed concern that she was receiving only medication and took her on as a client. Mary’s depression not only was a problem for her but also was potentially devastating to her infant. For this reason she was asked to come to the first session with her baby.

Like all infants, her baby was primed to engage her, without which he would not thrive. After birth, Mary’s son, Austin, reflexively oriented to her eyes, but he did not find warmth and nurturing. He found a blank stare. I immediately engaged him with positive facial expressions, a high voice tone, and animated prosody. I told Mary that, though she did not feel that she had it in her to engage with her son, his brain would thrive with engagement. To demonstrate, I began to hide my face behind my hands, peeking and then hiding again. Austin began to smile, as if awaken from a stupor. Mary did engage him, and to her astonishment, when he smiled she felt a little better each time. It became an antidepressant feedback loop.

The still face paradigm illustrates a snapshot of the devastating effects of parental depression on a child. In the still face paradigm a mother is asked to show no facial expression (Tronick, 2007). In response, the baby initially tries to entice her into playfully interacting. Eventually the baby becomes agitated, distressed, and finally gives up, looking despondent. If exposed to a still face for an extended period, the baby no longer approaches novel toys and receptivity and interactions with the environment shut down.

Parental depression acts to shut down the infant’s social brain circuits to neutralize what normally thrives on playful interaction. Because an infant’s brain has yet to develop cortical circuits, it relies on subcortical areas such as the amygdala. Because the amygdala is a relevance detector, it cannot tolerate the ambiguity of a still face. Neutral faces provoke more amygdala activity in children than in adults (Tottenham, Hare, & Casey, 2009). As infants mature they learn to tolerate neutral faces and ambiguity by increased cortical processing, especially in the prefrontal cortex (Casey et al., 2005). A fully operational prefrontal cortex helps us navigate through an often ambiguous world.

If you respond to a client with the psychoanalytically traditional “neutral” stance, presuming that he will develop transference, you may replicate his depressed parent.

We can derive significant implications from the still face paradigm for the long-term mental health of a child and into adulthood. If a child’s principle caregiver maintains an expressionless face for extended periods of time, as would have occurred with Mary’s postpartum depression, the child is deprived of critical emotional nourishment. Just as a balanced diet, sleep, and exercise are foundational for a healthy brain, so are animated interactions and facial expressions from parents. Positive or negative care can either turn on or off genes critical for the structure of the brain associated with affect regulation and social skills (Callaghan, Sullivan, Howell, & Tottenham, 2014). Failure to thrive because of lack of emotional nurturance can result in a lack of coherence in the salience network.

Mothers with postpartum depression tend to pull back from their babies. They tend to touch their bodies less as early as the second day after delivery (Ferber, Feldman, & Makhoul, 2008)). In response, the child’s essential needs are starved by the depressed mother’s flat affect, flat voice, neutral expression, and overall dulled interactions. Correspondingly, infants of depressed mothers whose speech prosody is flat show EEG patterns consistent with depression (Wen, et al, 2017)).

Infants of depressed mothers

- Have overactive right frontal lobes

- Have underactive left frontal lobes

- Have lower levels of dopamine and serotonin

- Display more aversion and helplessness, and vocalize less

- Have higher heart rates, decreased vagal tone, and more developmental delays at twelve months of age

- Have higher levels of stress hormones (Field, Johnston, Gati, Menon, & Everling, 2008)

Maternal depression during the first two years of a child’s life is the best predictor of abnormal cortisol production in children at age seven (Ashman et al., 2002).

Infants with a depressed mother are faced with a difficult predicament. They are immersed in a feedback loop in which there is only one way interact: to be sad together so that they can establish coherence to their relationship. Deprived of enhancing “self”organization through mutual growth with their mother, they may take on the mother’s depressive mood, irritability, and even hostile affect. When they encounter other people the only way they are able to expand in complexity and self-coherence is by establishing relationships around depressive features that were established with their mother (Tronick, 2007). They tend to develop implicit patterns of coping that entail avoiding others and inadequate attempts to self-comfort, resulting in negative affect and less engagement with the environment.

Because we are complex adaptive systems and by are nature open systems, maternal depression shuts down children’s attempts to thrive, stunting not only mood and behavior but also cognitive development. Mutually experienced depression constricts, closes down, rigidifies, and ultimately threatens both the mother and child, with no room to grow. The mother loses coherence and complexity while her child loses the opportunity to develop the full range of capacities to adapt to a complex interpersonal world.

As an open system, a child must acquire social input from others to maintain and increase coherence, complexity, and distance from entropy. Neither fixed nor chaotic, the child’s developing mental networks construct and thrive on adaptive meaningful experiences. Because the child’s development of viable mental operating networks is a self-organizing emergent process, all his interpersonal relationships contribute to coherent and unique implicit relational knowledge.

As an infant, toddler, child, adolescent, and adult, the individual progressively leaps to higher levels of organization while feeding on contextual interactions within and between each dimension. The family affects nutrition, physical activity, and attachment style, and they reside in a particular society with a particular socioeconomic and education level and within a cultural context. All these factors contribute to the individual’s “self”-organization.

GOOD-ENOUGH PARENTING

Whereas no attunement, such as with maternal depression, is devastating, hyperattunement also undermines psychological development. Half a century ago Donald Winocott pointed out that moderate matching was superior to perfect matching. Essentially, perfect is not good enough. Moderate matching is “good enough.” By this he meant that generally consistent but not perfect caretaking builds frustration tolerance for the child.

“Good-enough” parents could have prepared Clara for the often ambiguous, sometimes stressful life experiences that she later encountered. Instead, her parents offered low levels of affective matching, which spawned her insecure attachment. Yet, had she been offered the other extreme, instantaneous soothing, she may have had difficulty developing the vagal brakes necessary to activate her parasympathetic nervous system to counterbalance the sympathetic branch during or after stressful experiences.

Children who receive excessive attention and coddling become spoiled and narcissistic. As adults they may have a tendency to become pessimistic and passive-aggressive, having been trained by their parents that they can be gratified for no effort or even by simply whining. This passive behavior tends to overactivate their right hemisphere, promoting withdrawal and negative emotions, and underactivate of the left hemisphere with its associated positive emotions and proactive behaviors.

Good-enough parenting would have offered Clara moderate matching to bolster the resiliency of her autonomic nervous system, allowing her to rise to the challenge of stressful situations and then calm down afterward to recoup. Good-enough parenting would have allotted time before she was soothed, during which she could have developed the capacity to self-sooth by activating her parasympathetic nervous system to calm herself down.

The quality of the reciprocity within the parent-infant dyad—synchrony, matching, coherence, and attunement—offers the emotional nourishment critical for healthy development. The rhythm and timing of the interaction between mother and infant are key for the developing child to build the capacity to negotiate the nuances and subtleties of relationships. Sensitivity in the midrange is most predictive of secure attachment (Jaffe, Beebe, Feldstein, Crown, & Jasnow, 2001). When bonding/attachment is enhanced by repairing mismatches, healthy “self”-organization progresses. Just as Winnocott hypothesized, good-enough parenting offers flexible matching and reparation. Through encountering many moderate, well-coped-with stressors, the child best develops approach behavior, stress tolerance, and resilience. But when repair does not occur or there are repeated unsuccessful attempts to repair the ruptures, the child develops defensive and avoidant coping behaviors that undermines later relationships. These interactions for approach or avoidance correspond to the ability to differentiate between pleasurable and painful experiences (Berridge & Kringelbach, 2008).

A good-enough therapist is better than one who pretends to be perfect. Your imperfections model the real world. It is how you use your imperfections that determines the quality of therapy. Using the misunderstandings, conflicts, and points of tension in the relationship as the focus of resolution builds positive outcomes. Mismatches are a plus when resolved. Each self-organized transition, punctuated by emotional coherence and insight, may result in dopamine release from the ventral tegmental area of both therapist and client.

“Good-enough therapy” with moderate matching helps build frustration tolerance and the ability to self-sooth. The “impingements”—affective mismatches and misunderstandings—so inherent to communication represent the grist to be resolved in therapy. How a client may be angry with you offers a valuable opportunity not only to resolve but to leap to a higher level of shared meaning, promoting “self”-organization.

Either high- or low-sensitivity reparation may promote insecure attachment. Low-sensitivity reparations can occur during long-duration mismatches when infants are constantly overwhelmed with stress and so fail to develop coping skills. High sensitivity involves intense vigilance, where matching lasts too long, with little opportunity for reparation. Infants not given a chance to confront sufficient amounts of stress with support fail to develop effective methods of coping (Tronick, 2007). Through moderate matching the infant better develops coping skills and resiliency. The mother has an opportunity to find the midrange of comfort for herself. On the other hand, high or low matching forces the mother in one extreme or the other: blunting her affect or becoming too stressful.

Given that fathers excite and set limits, the research paradigm referred to as the Risky Situation (RS) serves as a measure of the father and child activation relationship. The RS may better measure attachment and affect regulation for boys than the Infant Strange Situation, which may be more appropriate for girls. In the RS, the father’s caregiving behavior tends to focus on arousal and excitement as well limit setting (Paquette & Bigras, 2010). In the Rough-and-Tumble Play (RTP) paradigm, the father activates but also sets limits. When fathers do not exercise dominance in the RTP with preschoolers they are more likely five years later to have poor emotional control and high levels of physical aggression, especially boys (Flanders, et al, 2009). RTP trains the child’s prefrontal cortex to learn to set limits on affect.

The reparation of the “messiness,” rather than synchrony, is key to change in therapy and development (Tronick, 2007). Inherent to complex adaptive systems, we thrive as open, curious people who strive to resolve misunderstanding, and this is a messy process. Through self-organizing interactions we become greater than we were before. Just as the parent-child dyad is a self-organizing system, so too is the therapist-client relationship. Therapist and client adjust to one another in a mutually regulated process. Each of us identifies and makes use of increasing amounts of meaningful information emergent from higher levels of shared understanding achieved together.

SELF-REGULATION AND ATTACHMENT STYLES

Why was Clara so emotionally tone deaf when it came to relationships? She did not encounter adverse childhood experiences or even maternal depression. How does someone like her come to feel so empty? Through preverbal interactions, an infant detects the mother’s subtle changes in affect through her voice pitch, prosody, and inflection and through the quality of touch, holding, and facial expressions. Nurturing parents tend to exaggerate joyful and encouraging facial expressions. Their babies learn to detect subtle changes in mood, perhaps even microexpressions (Beebe et al., 2010). These interactions build an implicit memory of attachment or, as John Bolby called it, the internal working model of how relationships work. Accordingly, the mother-infant dyad can be referred to as shared implicit relationship (Tronick, 2007).

Overlapping terms for attachment:

- Boding

- Internal working model of attachment style

- Pro-narrative envelopes

- Schemas of being within

- Themes of organization

- Relational scripts

The early patterns of adaptation have been referred to by a variety of overlapping terms. Whatever terminology you prefer, the bottom line for Clara was that the emotional neglect shaped her pattern of “self”-organizing thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. These impoverished interactions formed her self-identity and undermined her self-esteem, depriving her of a sense of lovability. Had she enjoyed a secure attachment experience, she would have been better equipped for durable affect regulation required for intimacy later in life. Her insecure attachment schema led instead to fear modulation and avoidance behaviors, which gave her little opportunity to cultivate self-esteem and social competence.

Attachments styles represent the self-regulation methods people use to cope with stress. While those who are securely attached use multiple strategies for dealing with stress, insecurely attached people are limited to just a few. As a result, their capacity to cope with interpersonal stress can be severely limited. Clara’s socially avoidant coping methods were compensated by approach behaviors, such as getting good grades. The attention that she received from teachers and from peers during class projects gave her a sense of a narrow range of belonging. Though positive, it restricted her self-esteem and competence to particular contexts.

The Neurochemistry of Attachment

- Early attachment experiences regulate the opioid system so that the developing child can generate feelings of comfort and buffer stress. Endogenous opioids also play a significant role in providing physical pain relief, and they are also associated with reducing social pain and enhancing pleasure (Curley, 2011).

- Endogenous opioids play a significant role in attachment as part of the infrastructure of feeling soothed with comfort. In fact, variation at one of the opioid receptor genes influences attachment behavior (Barr et al., 2008).

- Feeling soothed with less pain occurs in part through opioid release into the anterior cingulate cortex.

- Maternal nurturance stimulates the release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF).

- BDNF and N-methyl-d-aspartate expression and increased cholinergic innervation of the hippocampus enhance cognition (Liu et al., 2002).

- Higher levels of BDNF buffer cortisol in the hippocampus resulting from stress and promote ongoing plasticity (Redicki et al., 2005).

- A study comparing the brains of suicide victims with normal controls found lower mRNA levels of the genes for BDNF and receptor tyrosine kinase B (Dwivedi et al., 2003).

- Oxytocin release activates the vagus nerve and so the parasympathetic nervous system, which decreases heart rate and increases relaxation.

The interaction between social support and stress reduction occurs on many levels. The neurohormone oxytocin is a key regulator of emotional and prosocial behaviors (Neuman, 2008). Released by the hypothalamus during close interpersonal contact, it promotes trust and safety. There are many oxytocin receptors throughout subcortical areas, including the amygdala and periaqueductal gray, which when activated inhibit the stress response. Oxytocin receptors on the vagus nerve system activate the parasympathetic system, leading to stress reduction (Gimpli & Fahrenholz, 2001). Because lowering defensiveness is critical for interactions with others, oxytocin facilitates a calming effect along with the capacity of what some have referred to as “mind reading” (Domes, Heinrichs, Berger, & Herpertz, 2007).

Oxytocin has received much attention in both the mainstream press and neuroscience research. A variety of studies have shown that oxytocin appears to facilitate social interactions as well as genetic variations in the levels of stress reactivity, empathy, optimism, and self-esteem, corresponding to physical and mental health (Kumsta & Heinrichs, 2013). Researchers used nasal spray containing oxytocin with subjects and found increased levels of trust and generosity when playing economic games (Zak, Stanton, & Ahmadi, 2007).

SEPARATION, LOSS, AND BUILDING TRUST

Benny and Habib were two five-year-old boys. One had been separated from his mother, and the other lost his in a bombing. The care that they received afterward contributed to dramatically different outcomes. Benny was taken away from his parents due to his mother’s drug abuse and inability to care for him. Fortunately for Benny, his mother had reframed from drugs during the pregnancy, with the support of Planned Parenthood. But within a week postpartum depression led to her slip back into drug use, from which she never recovered. Benny was sent to one foster home after another. By age seven he was briefly placed with his grandparents’ custody. As his only family contacts, they began the process to legally adopt him, but when his grandmother began treatment for cancer they placed him back in yet another foster home. The visits from his grandparents faded as his grandmother entered a hospice program. Despondent and increasingly withdrawn, Benny’s first-grade teacher requested an immediate individualized education program meeting, to include staff from our mental health department and his latest foster parents. This meeting was meant to serve as a pivotal point that brought together a therapy team. Family therapy presented infrequent opportunities for his foster parents to learn to practice building trust and being a social buffer against all of the pain, abandonment, and mistrust (Baylin & Hughes, 2016). However, his foster parents had five other foster children, which provided a major source of their income. Both worked minimum-wage jobs, and they had little time to spend in therapy and were hardly engaged with any of their foster children.

Maternal separation leads to the following:

- The potential use of alcohol and other drugs (Francis & Kuhar, 2008)

- Alterations in the development of inhibitory neurons and changes in the connections of serotonin and dopamine neurons in the medial prefrontal cortex (Helmeke, Ovtscharoff, Poeggel, & Braun, 2008)

- The downregulation of gene expression for GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) receptors in the locus ceruleus, resulting in more norepinephrine (Caldji, Diorio, & Meaney, 2003)

- An upregulation of the gene regulating glutamate receptors (Weaver et al., 2016), which contributes to anxiety and depression and difficulty inhibiting negative affect.

- Epigenetic changes to the developing child’s stress response system

- Abnormally programmed gene expression in regions such as the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex (Moriceau, Shionoya, Jakubs, & Sullivan, 2009), priming the stress system to become vulnerable to turning on too often for the wrong reason

- Plasticity between the prefrontal cortex and amygdala skewing increasingly toward the amygdala and the rest of the stress system (McEwen & Morrison, 2013)

Habib’s situation was dramatically different in terms of support and culture. I met him during a trip to the Middle East as part of a group of mental health professionals training aid workers helping Syrian refugees. His back story was not only traumatic but horrific. One day in Damascus he and his friends noticed a metal object in an alley where they were playing. One of them hit the object with a stick and the bomb detonated. Everyone but Habib died instantly. He lost both legs, an arm, and an eye. Weeks after the incident more bombing killed both parents and his brother. After his hospital was bombed too, he was carried to a refugee camp at the Jordanian border by his only remaining relative. Then his uncle died a few days later. By the time I met him he was in the compassionate care of the women who were running the Souriyat Across Borders center in Amman, a hospice for those wounded in Syria. The warmth and love exchanged were heartwarming to witness.

The warm and nurturing environment offered Habib opportunities to adapt to the major challenges of his catastrophic injuries and trauma. With unwavering empathetic support of the rehabilitation center volunteers, his healthy development was made possible through the loving family- and village-like atmosphere. He was carried around the center with the same affection a highly nurturing parent would offer a baby. Though we were visitors, not core staff, his responsiveness to interactions with my colleagues and I was heartening. He apparently was developing an ongoing, coherent sense of self that allowed him to establish new relationships based on trust.

We can only speculate that he had previously formed a secure attachment to his parents before they were killed. This may have promoted an infrastructure of psychological resources that enabled him to respond to the warmth and care provided at the center. Habib had no explicit memory of the traumatic incidents. Based on the description of his anxiety and fear when he first arrived, he had made dramatic changes and was no longer hypervigilant and agitated. He was clearly building trust and was thriving in that loving environment.

The degree to which his implicit memory of the complex trauma dominated less was reflected by the way he engaged in the world. He appeared to possess a flexible autonomic nervous system through which he could turn on his sympathetic system when needed and his parasympathetic after the challenge have been met. Presumably, the regulation of the various calming neurotransmitters systems such as the endorphin and benzodiazepine receptors allowed him to recoup when needed and self-soothe. Flexible cortisol regulation permitted him to ramp up the neurochemistry to deal with a challenge during the daytime, and then during the evening he could turn down cortisol so that he was better able to restore resources, enhance positive immunological functioning, and promote better neural growth and plasticity for cognition.

One of the principle goals of therapy with children, adolescents, and adults is to promote secure attachment, to bolster not only interpersonal skills but also affect regulation and cognitive skills.

For Benny, who had developed significant mistrust of others, building trust was fundamental. The new learning was often punctuated by extinction bursts so that he often felt more mistrustful before feeling at ease with his foster parents and me. His defensive posturing, avoidance, and pushing me away before anticipating being abandoned again slowly dissipated until it became clear that it no longer worked and was not necessary in the new, safe context. Therapy oscillated between trust and no trust until trusting resulted in no bad outcomes.

In contrast, Habib had a therapeutic community embracing him. Despite his horrific trauma, both psychologically and physically, he received robust support through constant loving attention. Benny’s loose-knit foster home and weekly therapy did not compare. I had to weave together and promote a semblance for Benny of what Habib had. From a Western “clinical” perspective Benny was receiving “appropriate treatment,” while Habib was not, but it was dramatically lacking.

VARIATIONS IN ADULT ATTACHMENT

With all the attention focused on childhood, do residual effects of attachment extend into adulthood? Indeed, it appears that secure attachment noted in childhood is associated with a lower incidence of psychological disorders in adulthood, while on the other extreme, disorganized attachment is associated with dissociative problems. Anxious/ambivalent and avoidant attachment styles are both associated with the development of depression during adulthood. While avoidant style promotes depression based on a sense of alienation, anxious/ambivalent style promotes depression based on an internalized sense of helplessness and doubt (van IJzendoorn & Bakermans-Kranenburg, 1996).

In an attempt to assess adult attachment styles, Mary Main and her colleagues have developed the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI), based on eighteen questions assessing adult attachment history. There appears to be a correlation between attachment styles in childhood and adulthood. For example, the AAI-identified preoccupied style shows strong similarities to the ambivalent style. Ambivalent babies tend to have preoccupied parents, and they later become preoccupied adults themselves who are obsessed with love and loss. They tend to be emotionally underregulated and prone to overreact to interpersonal stress. Attachment predicts adult capacity for intimacy and conflict resolution. A meta-analysis of the AAI studies indicates that insecure attachment is correlated with anxiety and mood disorders (Cassidy, Jones, & Shaver, 2013).

Children/Adults

(Infant Strange Situation)/(Adult Attachment Inventory)

Secure Free/Autonomous

Avoidant Dismissing

Ambivalent Preoccupied

Disorganized Unresolved

The preoccupied pattern typified the predicament for Carl. He repeatedly checked with his partner, Rob, about the look on Rob’s face that Carl interpreted to mean that “he was done me.” Though Rob immediately reassured him that all was okay between them, Carl would follow up by asking, “You’re sure about that, right?” Frustrated with the persistent questions, Rob sighed deeply. Carl threw up his hands and said, “You see! Why are you sighing? What did I do?” Rob told him to “get help for the sake of our relationship,” which brought him into therapy.

The AAI-identified dismissive style shows strong correspondence to the identified avoidant style of attachment identified in children in the Infant Strange Situation. Avoidant children grow up to be dismissive adults, learning to deal with parental insensitivity by shifting attention away from their emotions. They tend to be little aware of the feelings of others. Dismissive adults tend to state that they remember little of their childhood, not because of repressing difficult memory but because few emotionally relevant events occurred while growing up. Dismissing adults tend to be overregulated and rigid even though separations still provoke spikes in cortisol.

The dismissing attachment dilemma was illustrated by Sharon and Tyler in a couples counseling session. Sharon complained that Tyler was “not there for me.” He snapped back, “I’m with you all the time, except when I’m at work! What do you want me to do, quit work?”

“No, I mean that you are remote.”

Tyler rolled his eyes and then turned to the couples counselor for an explanation. The counselor asked him what his parents’ marriage had been like. Tyler shrugged his shoulders. “Fine, I guess. No abuse, if that’s what you’re asking.”

Still not satisfied, the counselor pressed further. “Can you tell me more details of your childhood and family life?”

Tyler shook his head: “I really don’t remember much of my childhood.”

“Birthdays, holidays?”

“Just like any other days.” His parents reportedly did not make those days special in any way—no parties, no family gatherings. With very few emotionally relevant events, every day looked the same, with nothing out of the ordinary to remember.

Avoidant as a child and dismissive as an adult, Tyler saw his physical presence with Sharon as meaning he was there all the time with her—it was that simple for him. But not for Sharon. Tyler possessed very little self-awareness, so he had little awareness of Sharon’s emotional needs. His salience network was underdeveloped. Learning to be aware of his own emotional feelings facilitated sensitivity to Sharon’s.

ATTACHMENT AND THE MIND’S OPERATING NETWORKS

As noted in Chapter 1, the organization of a coherent and durable sense of self is maintained by the mental operating networks. Clara’s dysfunctional adult relationships undermined the development of and balance among those networks. When a relationship became emotionally stressful, she pulled her away, trying to avoid the pain of what felt like rejection. Her executive network was compromised by attention turned away from the present moment and instead inward for self-reflection with her default-mode network (DMN), which she used to replay the story lines of conflicts and to anticipate more of them.

Because Clara developed a dismissive attachment style, her capacity for insight about others was compromised. She found reflection about relationships difficult, in part because of underdevelopment of both her DMN and salience network. If she had been traumatized, switching between her compromised executive network and DMN may result in impairments in the functional connectivity between them (Daniels et al., 2014). Overall, therapy promotes flexible and socially adaptive shifting between her executive network, salience network, and DMN.

Increased coupling of the salience network and DMN has been associated with egalitarian, self-sacrificing, and prosocial behavior (Dawes et al., 2012). The DMN does not begin to develop until the early latency period, to participate in the emergence of social skills. It also offers a mental platform to link social cognition and self-referential thought (Mitchell, Banaji, & Macrae, 2005). As the network that developing children cultivate thoughts about themselves while reflecting upon their interactions with others, Clara used her DMN to maintain continuity while increasing complexity in her relationships: our DMN provides a means to reflect on our relationships, and our salience network provides a means to empathize.

These mental networks toggle back and forth to meet social demands. A burst of activity in the salience network signals important changes in the body in response to social situation and that it is time to snap out of the DMN and activate the executive network to make whatever adaptive behaviors are appropriate. A change in the social environment that may result in the recognition in social inequality and rejection signals the salience network to work with the DMN to reflect on what occurred and the feelings associated with it (Masten, Morelli, & Eisenberger, 2011).

A secure adult flexibly shifts from the DMN to the executive network to focus attention on cognitively demanding tasks while maintaining activity in the salience network for self-awareness. In contrast, people who are not able to shift flexibly among networks sometimes have trouble focusing on and adapting to changing circumstances in their immediate environment. This is what happened to Scott, as I discovered during his evaluation for attention deficit disorder. Interestingly, he held a graduate degree in chemistry, which he earned with high honors, and he had no difficulty with attention when studying alone. But he did find it difficult to focus on studying when people were in the room, even if they were very quiet.

Scott’s developmental history revealed much of the context to his problem with focus. He was the last born of a family of eight children and was told that he was an “accident.” Because his parents made it clear that they were “done” parenting, his siblings became his surrogate parents. Yet, they were also children and engaged in their own sibling rivalries. Scott grew up hypervigilant to all of their conflicts to ensure that he would not get roped in. As an adult with a preoccupied style of attachment, his external locus of control in the presence of others compromised the balance and flexibility between his executive and salience network.

RECIPROCAL SELF-AWARENESS

Implicit memory forms the undercurrent of interactions among family members who can share a brief glance that means much more to them than to observers outside the family—these are learned by children as part of development. Implicit communication patterns resonate to increasing degrees in people who have spent the most amount of time with the family. When they form friendships, get married, and have close work relationships they can run the risk of overinterpreting or underreacting to implicit nonverbal interactions with others outside their social networks. It is the task of therapy to discover these patterns and help clients use and modify them to conform to flexible healthy relationships.

A long-standing practice in therapy is to make note of a client’s expression, a sigh, or crossing of the arms that might denote a sudden implicit-emotional shift in the relationship. A therapist may say, “Look, what just happened between us?” This question punctuates the moment, making it memorable, and shifts the focus to the implicit attachment dynamics inherent to the therapeutic relationship.

The earliest recollections of struggles for love and safety may not be apparent in explicit memory but can be accessed implicitly through the transference relationship (Cozolino, 2017). The capacity to maintain self-awareness while reflecting on the thoughts, emotions, and behavior of others represents a key goal of therapy. These skills are dependent on our ability to consider another person’s point of view while reflecting on our own.

The overlapping concepts of interpersonal relatedness:

- Theory of mind

- Mindsight

- Intersubjectivity

- Mentalization

- Attunement

- Social intuition

- Social intelligence

According to outcome research, clients tend not to completely reveal their feelings about therapy when asked in the session. Follow-up outcome questionnaires have become standard practice to discover negative concerns that the client has about the therapy that have not been addressed. With this new information, repairing the impingements and working through and earning security can be addressed.

The implicit feeling of therapy has a major effect on what clients reflect on between sessions. Derived from their implicit memory system representing their emotional tone, clients build nonconscious knowledge of relationships that tend to be continually replicated. Gaining insight into how these emotional patterns are replayed helps change the narrative in the explicit memory system. Implicit patterns of relating are learned slowly through healthy, (good-enough) relationships. Heightened affective moments signify the coregulation of shared implicit meanings (Beebe & Lachmann, 2002).

STORYTELLING AND THERAPEUTIC NARRATIONS

Since the advent of language, telling stories has served multiple functions. As a means of enculturation, members of a society can agree on a common origin and meaning to their existence and establish and reinforce morals, ethics, and general customs for societal cohesion. Storytelling, sometimes called the narrative, provides a means through which a therapist helps a client to organize adaptive self-referential meaning.

Stories serve a fundamental role in the interaction between parent and child. Storytelling represents an important part of the bedtime ritual. Stories capture attention if laced with suspense, drama, and tension and can be the most comforting way to learn life lessons when offered with resolution. They carry an emotional arc fused with cortisol in the beginning; the tension rises, with the child’s attention riveted, eyes widened, heartbeat quickened, and then a resolution is facilitated by a brave and kind hero, with the child enjoying the climax with boosts in dopamine and oxytocin. This ritual offered on a regular basis primes the oxytocin system, increasing trust with the storyteller (Zak, 2012). Because listening to stories brings the combined release of cortisol and oxytocin when the plot factors in empathy, it puts limits on the elevation of cortisol. Like therapy, the story teaches how social support and resiliency can work together.

Children and their caregivers co-construct narratives that describe and helps children make sense of their existence. Through co-constructing narratives children learn how to develop meaning and a sense of belonging. These narratives contribute to the formation of the explicit memory system within which autobiographical and episodic memories contribute the self-referential information, which the DMN taps to reflect on, to develop meaning in relationships.

Therapy entails co-constructing adaptive new narratives to be replayed during clients’ DMN periods. These storylines instill social support, slowly building trust in people who deserve trust, and a sense of security. Through the self-referencing narrative, clients learn to imagine conversations with socially supportive storylines. Co-constructive narratives offering uplifting emotional arcs, soothing storylines, or Zen koan-like stories entice clients to search creative solutions to their problems. Having heard a story seemingly related to someone else but in actuality meant for the client can be imbued with a solution focus (O’Hanlon & Rowan, 2003).

Self-referential story loops comprise narrations that we tell ourselves about our relationships. Distressing events are not dwelled on in the DMN for securely attached people as much as they tend to be with insecurely attached people. Sad stories tend to have a happy or at least hopeful ending for the securely attached, whereas an insecurely attached person fixates on negative aspects of a relationship.

Creating unexpected moments of empathy and compassion can trigger positive prediction errors. When a client sees you smile unexpectedly, it induces a release of dopamine, which is received by her nucleus accumbens so that she becomes motivated to create the conditions for that to recur. Such moments create a window of opportunity to coconstruct new narratives that build trust and hope.

In family therapy parents can learn to develop warm and engaging expressions toward their children, while storytelling fosters trust (Baylin & Hughes, 2016). The stories may include information about family conflict needing to be resolved. When the parents stay open and engaged with each other and with their children, the tension or misattunement can be worked through.

Narratives co-constructed in therapy are best if multilayered, because clients experience innumerable events in their life, and the contexts are constantly changing. No single narrative modeling their experiences will suffice. Since they interact with multiple people, flexible and adaptable narratives are effective. The fluid and changeable nature of their social experiences requires narratives that are durable with multilayered social contexts.

Collectively, the social factors explored in this chapter illustrate why the quality of the therapeutic relationship has been consistently found to be the most significant factor affecting outcome. For this reason, some have borrowed the real estate cliché to say that the three most important factors in therapy are relationship, relationship, relationship.

CULTURAL VARIATIONS

We coevolve with others within an interpersonal field, community, and culture that all provide the social feedback loops that offer context and meaning to our experience. Based on these culturally bound contextual reference points, we communicate to others and set up expectations about the values or the potential effect of our behavior. From infancy on these culturally relevant factors frame our relationships.

Infants born to parents in northern European cultures respond to adults who are not their parents differently than do infants born within an Efe (Pygmy) family. While infants in northern Europe may find it difficult to be comforted by anyone other than their parents, an Efe infant probably would find it easier to interact with everyone on a daily basis. These individuals have multiple attachments, so there are sharp distinctions between self and other (Tronick, 2007).

The Infant Strange Situation paradigm has been used throughout the world, revealing a preponderance of particular ethnic attachment styles. For example, in northern Germany and Scandinavia there are relatively more people with avoidant patterns of attachment. It is not uncommon for mothers to step away briefly, leaving their infants unattended at home or outside of supermarkets. A well-publicized incident typifies this generalization when a Scandinavian couple visited Manhattan. They left their baby in a stroller outside the supermarket and went in to purchase food. Child Protective Services arrived like a SWAT team, applying a protective perimeter around the baby. The parents emerged from the market and were alarmed to find people hovering around their baby. When the Child Protective Services workers asked why they left their baby outside, they responded with astonishment, saying “What do you mean? We do that at home all the time!”

In Japan there is a preponderance of ambivalent and hard-to-soothe infants. Mothers and infants are rarely separated. Babysitting is rare, and when it occurs it is generally with grandparents (Miyake et al., 1985). Among kibbutzim in Israel, babies have been reported to become anxious by the entry of strangers in attachment testing situations. Terrorist attacks create a xenophobia reflected in their parents and modeled by children, so that strangers are distrusted (Saarni et al., 1998).

When I lived on a kibbutz in the early 1970s I was intrigued by the group child-rearing practices. Instead of children living with their parents, they lived in separate quarters, like a dormitory, and the adults would take turns taking care of them. Bruno Bettelheim argued that this practice was meant to rid them of the inward-oriented, self-conscious personality of the ghettos of Europe and help them become more oriented toward modern society. With an extreme deemphasis on the roles of their parents, the children presumably developed multiple attachments. However, in retrospect, attachment was compromised.

Within the Gusii culture in Kenya, a mother does not often engage her infant in face-to-face play. When mothers are asked to engage her infant face to face, just as the infant responds excitedly, the mother turns away. In contrast, among the !Kung in the Kalahari infants spend 70–80 percent of their first year in constant physical contact with their mother. The remainder of the time they are handled by someone else. They are nursed four or more times an hour for short bouts (Konner & Worthman, 1980). Babies and the adults engage in animated face-to-face interactions.

Given the wide range of diverse interpersonal styles of relating, the practice and training for psychotherapy have attempted to adjust accordingly. Approximately forty years ago, while teaching counseling on the Navajo Reservation, I adjusted the conventional expectations regarding relationship-building skills, such as eye contact. Among Navajos, eye contact was discouraged and suggests disrespect. Also, in contrast to the Rogerian and later motivational interviewing concept of active listening, the Navajo conversational style was relatively more authoritarian, with the counselor telling the client what they ought to do. During the period I wrote this chapter I gave a seminar in Albuquerque and a Navajo counselor who attended approached me during the break. He maintained engaging eye contact as he asked a question. I noted that his eye contact was strong, and I asked him about the traditional practice of having little eye contact. He responded with a broad smile and said, “I’m well acculturated in Anglo society.”

Because of these cultural variations in communication styles, almost all psychotherapy training includes cultural competence as part of the curriculum. The training programs that I directed in twenty-four medical centers were all required to weave cultural competence into every aspect of training.

As psychotherapists we should not only be sensitized to the culture but also be aware of the implicit biases and microaggressions that we may make with clients of diverse backgrounds, whether it be culture, race, or LGBTQ differences.