NINE

Transcending Rigidity

Start by doing what’s necessary, then do what’s possible, and suddenly you are doing the impossible.

—Francis of Assisi

Scott and Annie fell into depression like it was a black hole. Previously, both had good-paying jobs, their two children were reasonably well adjusted, and they lived in a quiet, upper-middle-class neighborhood close to parks and shopping. When Annie lost her job she also lost her desire to do anything with the family. As her life constricted into rigid isolation, her whole family began to feel the gravitational force of the black hole. Scott became easily stressed and increasingly depressed. And with foul moods their children isolated themselves to their rooms with their computers. After a year of isolation from family and friends, they accepted a dinner invitation from their neighbors. When they discovered that one of them was a psychologist, the conversation quickly shifted to how miserable they felt. Annie complained of having no energy and feeling “stuck in a dark hole” all the time. Her doctor told her that she had chronic fatigue syndrome, then the diagnosis shifted to fibromyalgia, and then finally to prediabetes. She said, “They don’t know what’s up with me. I just feel ill and can’t seem to get out of the hole.” She turned to Scott, wagging her finger, “And this guy is no help!”

Scott shrugged his shoulders, hesitated, and then nodded his head in agreement. “Truth is, my job is torture. There are deadlines that I can’t meet and a boss I can’t please. The only time I have alone is during the two-hour bumper-to-bumper commute.” Annie interrupted, “We have been on a boatload of antidepressants. Aren’t you glad you’ve invited us?”

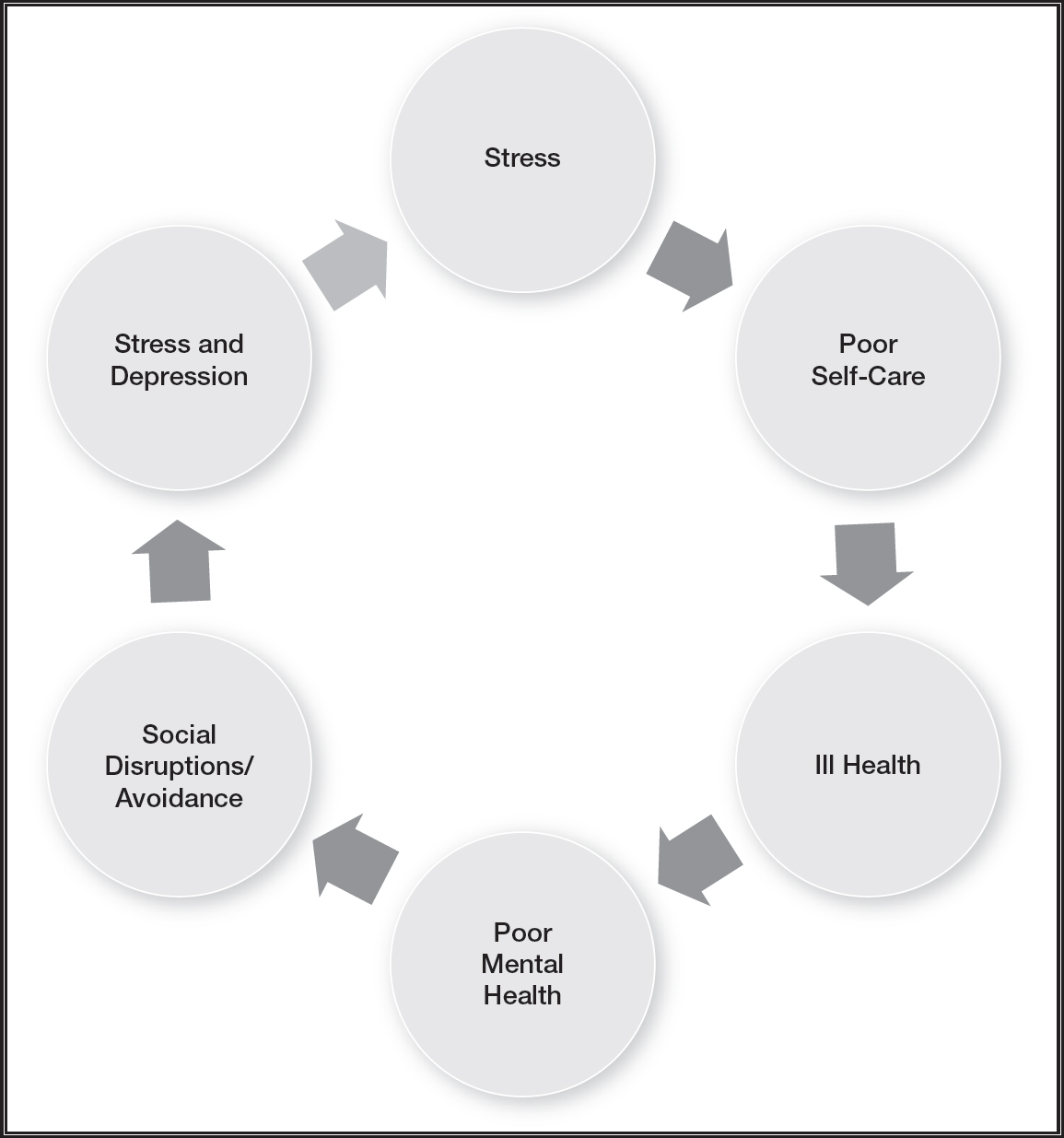

Both Annie and Scott became increasingly depressed, initially in response to stress and then isolation, poor self-maintenance, increasingly poor health, and the way they conceptualized their situation. This chapter explores the spectrum of depression and the multiple and interacting contributors. Because multiple factors contribute to depression, therapy must incorporate simultaneous interventions.

DIFFERENT SHADES OF BLUE

How common is depression, and is it a modern syndrome? Generally, one in ten people in the United States have suffered from depression once in their lives. Studies of current hunter-gatherer societies and extrapolating back in time to our ancestors indicate that depression was as common as among people in modern societies (Stieglitz et al., 2015). Despite its common occurrence throughout prehistory and recorded history, depression is not a discrete psychological disorder with one etiology and a clear set of symptoms (Maletic & Raison, 2017).

Women outnumber men with depression two to one. Women seek therapy for depression more often than men do, and when they do their symptoms appear on the surface like what is commonly regarded as depression. It was easier for Scott to talk about stress than depression. Indeed, he did suffer from a mix of stress and depression, but the stress symptoms were more obvious. Men may exhibit symptoms that can be misconstrued only as chronic stress, irritability, anger, and recklessness when depressed. Despite the differences, one common factor was that both Annie and Scott became ill, which increased their depression.

Gene-Environment Interactions

Because depression is not a finite disorder with one etiology and one recommended treatment, reductionism has led us down a blind alleys. The quest to find a gene that specifically causes depression has come up empty. Despite meta-analyses of genome-wide association studies involving thousands of subjects, no specific genes responsible for depression have been identified (Major Depressive Disorder Working Group, 2013). Genes, the environment, and individual behavioral differences interact.

As described in Chapter 3, one of the most widely researched gene-environment interactions associated with depression has been on the “short form” of the gene for the serotonin transporter. Compared to the long version, the short version is associated with an increased risk, not a cause, of developing mood disorders. The risk increases in response to stress, especially if the stress occurs in childhood (Sharpley, Palanisamy, Glyde, Dillingham, & Agnew, 2014). In people who suffered adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) or possess the short version of the serotonin transporter gene, the structures in the salience network could be undermined. On the other hand, social support can moderate the effects of the serotonin transporter gene, minimizing the risk of depression (Kilpatrick et al., 2007).

More women than men have the short version of the serotonin transporter gene, which is associated with anxiety and depression when switched on by threats or stress. The process is not as simple as once thought: the short version does not cause depression but, rather, tends to increase a person’s sensitivity to the environment, whether stressful or positive (Homberg & Lesch, 2011). In fact, those with the short form and who also receive enhanced nurturing during childhood are more resilient later in life than those without the short form and had also received enhanced nurturning.

The interaction among ACEs, the short version of the serotonin transporter gene, the reduction of the affect regulatory neurocircuits, and the development of major depression can take many forms (Frodl et al., 2010). People who endured ACEs are at greater risk for developing depression and receptivity to treatment (Uher, 2011). ACEs combined with the short version and subsequent stress have been associated with an increased risk for suicide (Sharpley et al., 2014). Sociocultural factors can trigger epigenetic affects by the stress, inducing power disparity between men and women. For example, Annie crashed into the glass ceiling of nonequal pay for the same job. After being passed up for promotions, she took on more work delegated to her by the promoted men that she previously supervised. Eventually, she went on disability with a diagnosis of depression.

Neurotrophic Factors

One of the ways that our brain stays healthy is through the release of neurotrophic factors (meaning growth-enhancing substances). They enhance flexibility (neuroplasticity) and growth (neurogenesis). When these factors are not operative, our brain begins to shut down into rigid mood states we call depression and ultimately dementia. A variety of neurotrophic factors have been identified, including brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), glial-cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), fibroblast growth factor, and nerve growth factor.

BDNF is the most researched of the neurotrophic factors. It promotes brain growth, neuroplasticity, and neurogenesis, especially in the hippocampus. While it has been shown to enhance cognition and stabilize mood, its depletion or absence is associated with depression and dementia. Accordingly, people with low BDNF, such as those who are obese, tend to have smaller hippocampal areas and are also more inclined to suffer from depression.

Though BDNF has been getting all the press, GDNF has increasingly been shown to play a crucial role in neuronal and glial health, and so with cognitive functions, mood regulation, and resiliency to stress. It is an important modulator of monoamine synthesis and so plays a key role in the development and survival of dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine. These neurotransmitters are the main targets of many of the antidepressant medications. Each plays important roles in mood stability, energy, and motivation.

Genetics, Epigenetics, and Depression

The gene regulating BDNF synthesis has two different alleles, leading to different genotypes: People who carry the Met variant of the gene regulating BDNF synthesis and those carrying Val variant (Maletic & Raison, 2017).

- The Met/Met genotype is associated with decreased BDNF regulation and distribution; with structural brain changes associated with depression, memory deficits, and decline in reasoning skills; and with reduced gray matter volume in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, orbital frontal cortex, amygdala, and hippocampus.

- The Val/Val genotype is associated larger hippocampal volume and, if depression is present, a better response to treatment.

- Epigenetic changes, including hypermethylation of the BDNF gene, have been proposed to be a factor in depression and suicidality and may provide the platform for some of gene-environment interactions (Lockwood, Su, & Youssef, 2015).

- Epigenetic factors play a role with some women having a mutation in CREB-1 gene, which is turned on by estrogen and is associated with depression.

- Altered expression of GABA and glutamate transmitter genes has been found in depressed people who ended their lives with suicide (Fiori & Turecki, 2012).

A decline of BDNF and GDNF leads to demyelination. Diminished neurotrophic support alters energy supply and increases oxidative stress and neurotoxicity, all contributing to depression (Maletic & Raison, 2017). These corrosive dysregulations further contribute to depression by impairing the brain structures that regulate mood and executive function including the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (PFC), orbitofrontal cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala.

Impairment in the ACC, a key part of the salience network, is associated with those depressed clients who have resigned, do not perceive conflict between the demands in the environment and their state, and have lost the will to change. With impairment to the dorsolateral PFC, a key part of the executive network, they perceive the conflict between their environment and state but are unable to activate goal-oriented behavior to facilitate change.

Inflammation-Depression

Many illnesses cause and exacerbate depression. Depression also makes many illnesses worse. An extensive study of approximately a quarter million people from sixty countries found that having a medical condition increased the risk of also having depression by 300–600 percent. The risk of depression increased to 800 percent with two medical conditions (Moussavi et al., 2007). Those illnesses associated with higher levels of inflammation are also associated with more depression than are illnesses with less inflammation (Raison & Miller, 2001). Inflammation appears to represent the central factor.

Both Annie and Scott suffered from the positive feedback loop between depression and their poor health. Scott was diagnosed with metabolic syndrome and Annie was warned that she was developing type 2 diabetes. The synergistic effect between depression and illness goes beyond the obvious that they were less motivated to engage in behaviors that manage those illnesses. With their energy dissipating, neither of them felt like doing the very things that could lift their depression.

Risk Factors for Depression Also Associated With Inflammation

- Medical illness

- Psychosocial stress

- Sedentary lifestyle

- Obesity

- Diabetes

- Metabolic syndrome

•Cardiovascular disease

- Infection

- Gut microbiome imbalance (dysbiosis)

- Autoimmune disorders

- Diminished sleep

- Social isolation

- Poor diet (e.g., skewed ratio of omega-3 to omega-6 and high in simple carbohydrates)

- Smoking and second- hand smoke

- Air pollution

- Winter for those with seasonal affective disorder

There are significant biological links among depression, inflammation, and ACEs. Early-life trauma or deprivation are associated with an elevated incidence of depression and illnesses such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease (Raison, Capuron, & Miller, 2006). Depressed people with a history of early-life trauma tend to have abnormal levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines (PICs), such as interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor. These associations predict unfavorable courses of illnesses and treatment outcomes for depression (Nanni, Uher, & Danese, 2011). Inflammation represents a common factor between ACEs and adult poor health (Danese, Pariante, Caspi, Taylor, & Poulton, 2007).

Depression that runs in families tends to co-occur with various inflammatory illnesses. For example, some families that are positive for major depression are also positive for fibromyalgia and irritable bowel syndrome (Wojczynski, North, Pedersen, & Sullivan, 2007; Raphael, Janal, Nayak, Schwartz, & Gallagher, 2004). Factoring out second-hand smoke, children and adolescents of depressed parents are at an increased risk for asthma and other respiratory conditions (Goodwin, Wickramaratne, Nomura, & Weisman 2007).

Chronic inflammation can develop as a result of poor self-care practices, obesity, and/or metabolic syndrome and is associated with autoimmune disorders and cardiovascular disease, which are all associated with depression. These multidimensional causal interactions can impair social competence and contribute to interpersonal conflict, which combined with depression and hostility are associated with elevations in PICs. The relationship between depression and hostility can increase the risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular illness, as inflammation increases insulin resistance (Suarez, Lewis, Krishnan, & Young, 2004). The more severe the depression, interpersonal conflicts, and hostility, the greater the mortality risk.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, by 2009 suicide surpassed auto accidents as the number one cause of injury-related death in the United States. Though many factors contribute to suicide risk, it is important to note that as depression associated with inflammation increases, so does suicide risk. Plasma concentrations of the PICs (interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor alpha) are higher, while levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-2 are lower in those attempting suicide, compared to depressed people who did not attempt suicide or nondepressed people (Janelidzes, Matte, Westrin, Traskman-Bendz, & Brundin, 2011).

Overall, an association between depression and chronic inflammation has been a consistent finding in studies of people across the life cycle. Causal interactions occur among perceived stress, loneliness, depression, and inflammation (McDade, Hawkley, & Cacioppo, 2006). These interactions have gained so much interest that a syndrome referred to as “sickness behavior” has been consistently associated with depression.

Sickness Behavior

Since the mid-1990s, the range of symptoms associated with depression and chronic inflammation have been dubbed “sickness behavior” because those afflicted, like Annie, appear, feel, and behave as if they are ill. Sickness behavior is characterized by disturbances in mood, cognition, and neurovegetative behaviors that mimic major depression and contribute to it (Dantzer & Kelly, 2007). Chronic inflammation and sickness behavior associated with it are characterized by disruptions in appetite and sleep, as well as decreased social and self-care behaviors and deficits in learning and memory. When feeling overwhelmed with all these symptoms of sickness behavior, Annie felt ill, so she acted ill. Her sedentary behaviors inadvertently made her more depressed and feel even more ill. She thought that she needed to “recoup” or “get over” the “illness” by resting. When she made a brief attempt to pull out of the self-perpetuating spiral, she initially felt worse over the short term, so she disengaged before discovering that over the long term she would have gradually felt better had she stayed engaged. She escaped the brief period of discomfort, so she did not see the long-term benefit of engagement, that is, until she began therapy.

Symptoms of Sickness Behavior

- Feelings of helplessness

- Depressed mood

- Cognitive deficits

- Loss of social interest

- Fatigue

- Low libido

- Poor appetite

- Somnolence

- Pain sensitivity

- Anxiety

- Anhedonia

It is important to put in perspective how sickness behavior plays a role in adaptation. Considering that during our hunter-gatherer 50 percent of people died by adolescence of various types of infections and various pathogens, our immune functions and specifically short term inflammation became a prominent defense.

However, chronic inflammation adversely affects the central nervous system, resulting in lethargy and withdrawal. The effect of PICs on the basal ganglia slows movement and leads a person to lie low and conserve energy while the immune system fights off the threat. When ill, we hunker down and avoid movement, involvement with others, and engagement in long-term goals as we wait until our body fights off the virus or infection. In short, the identification of infection or a virus, facilitated by the activation of the body’s inflammatory response system, is also a powerful depressogenic stimulus (Maletic & Raison, 2017).

There are major metabolic costs of mounting a fever. The activation of the immune system promotes sleepiness, especially slow-wave sleep and suppression of REM sleep. Also, when awake, slowed movements, social withdrawal, fatigue, and diminished appetite all conserve energy to fight off whatever ails us. The behavioral aspects of sickness behavior, such as irritability, anger, and even anxiety, could be understood as methods of keeping others away for the benefit of both the ill person and those immediately nearby.

Sickness behavior is essentially depressive behavior. When Annie and Scott failed to engage in regular physical activity and withdrew socially, they simultaneously potentiated depression and inflammation. Because they felt ill, less motivated, and less capable, they failed to exercise and to engage socially and experienced more depression. Like sinking in quicksand, they sank in more depression brought on by inflammation and then sickness behavior.

PICs contribute to depression by altering the levels of dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin through a variety of pathways that reduce the availability of their amino acid precursors, such as tryptophan, which is necessary for serotonin synthesis (Schiepers et al., 2005). Low levels of these neurotransmitters represent just one of the many inflammatory contributors to depression and anxiety. PICs also have significant effects on the hypothalamus and the hippocampus, which can play a role in sickness behavior.

PICs can activate the enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), which depletes tryptophan, the primary amino acid precursor of serotonin. Thus, IDO indirectly lowers serotonin. IDO catabolizes tryptophan into kynurenine and its metabolite, quinolinic acid. Elevated IDO and quinolinic acid have been associated with increased suicidality. Inflammation-induced quinolinic acid can spur excitotoxicity through direct activation of NMDA receptors.

Loss of neurons as well as glia cells in mood-relevant brain areas such as the subgenual ACC has emerged as one of the hallmarks of depression. Compromised functional and structural integrity has been found in the amygdala-ACC circuitry, along with reduced ACC, amygdala, and hippocampal volumes, which are associated with greater risk for depression (Pezawas et al., 2005).

PICs increase the activity in the default-mode network and the salience network. In so doing, Annie’s physiological condition became her concern, rather than engaging in the immediate environment. As she succumbed to withdrawal and inactivity, her depression took a downward spiral. Less activity, lower energy to fuel movement, and fatigue led to feelings of anhedonia, so she had less motivation to maintain social ties. Her social withdrawal led to less pleasure, more time for rumination on the futility of making any effort, and feelings of worthlessness. Her therapy reversed this retreat. Increasing social support has long shown to buffer stress and help lift depression and has been shown to lower levels of inflammation.

It important to make clear to depressed clients that feeling ill makes them act ill and that if they behave like they are ill, the feelings of depression will increase.

Stress-Depression Synergy

Scott’s depressive downward spiral began with stress. Changes to his neurotransmitters and neurohormones associated with stress led to progressively tenser and more depressing experiences. The commute to work and dealing with Annie’s depression combined to prime his stress circuits. As Scott’s depression increased, his stress toleration decreased. And as stress increased, so did depression.

Depression is associated with dysregulation of body’s threat detection circuits, including the sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, and the immune system. When out of balance, mood disorders, illness, and stress-induced release of epinephrine and norepinephrine combine to stimulate the release of PICs. Increased activation of his sympathetic nervous system and low activation of the parasympathetic branch increased inflammation and depression.

The link between anxiety and depression is associated with disruptions in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis:

- Increased levels of cortisol, norepinephrine, and epinephrine (adrenalin)

- An enlarged and hyperactive amygdala

- Enlargement of the pituitary and adrenal glands, elevated corticotropin-releasing hormone, and adrenocorticotropic hormone hypersecretion

During his third therapy session Scott revealed that his mother was an alcoholic. In response to postpartum depression, she started to drink just after he was born. According to family members, she spent much of his first year in her bedroom, and he spent a great deal of time in the crib until his father came home from work. Studies that indicated that babies of depressed mothers have hypersecretion of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) associated with maternal deprivation or severe stress. Their altered set point for CRH neurons and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity contributes to a tendency to overreact to stress during adulthood and develop depression.

Even short-term stress can prime depression. The levels of dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin can drop for ninety minutes after stress. Lower levels of all these neurotransmitters have been associated with depression. For example, low levels of dopamine are associated with psychomotor retardation and with decreased blood flow to the left dorsolateral PFC. Because the left PFC, relative to the right, can inhibit amygdala activity, a depressed and anxious person like Scott needs to kindle the left PFC through approach behaviors.

Figure 9.1: The synergistic depressive effects of poor self-care, ill health, social withdrawl, and stress.

The combination of depression and excessive amygdala activity promotes anxious and depressed memories (Davidson et al., 2003). Scott’s emotional state when particular memories were encoded made it more likely to recall memories when he was that particular mood, referred to as state-based memory. In other words, when he was depressed and anxious, it was more likely that he recalled memories laced with both anxiety and depression. This did not mean that there weren’t things that happened in his past that were positive. Essentially, state-based memories are the emotional lens that he used to recall memories.

The same applied to his perception of events in the present. His anxious and depressed emotional state tainted his perception, making neutral events feel negative. During periods of depression and anxiety this resulted in attaching emotional significance to normally trivial events and considering them important.

Scott developed a tendency to believe that the challenges at home and work meant either that he was cursed with bad luck or that God was testing him in some way. He wasn’t quite sure which of these possibilities was the reason for his stress, but he believed that it was all happening as part of his fate.

Social Stress and Depression

Scott suffered from significant job stress in part because his stress level was high before he arrived at work. As he got ready to leave each morning, Annie told him how badly she felt and that he was partly at fault. During and afterward, he felt an agitated increase in depression. Then he endured the two-hour commute while ruminating on the depressing and anxiety-provoking events. He grew convinced that there was little in his past to feel good about.

Already stressed by the time he arrived at work, he tried to hide out from his boss and his coworkers. This combination of withdrawal and avoidance drew scrutiny and criticism from not only his boss but also his coworkers. His brain was primed for more threat, and he assumed that it would come from all of them. With his amygdala sensitized by cortisol, his anxiety became more likely during his periods of depression. Contributing to a downward spiral, an overactive amygdala led to elevated levels of norepinephrine, and CRH reduced his serotonin level, increasing the risk of depression as well as anxiety.

Suffering rejection that is difficult to reconcile can deflate self-esteem and self-respect. Worthlessness to others can promote social emotions such as shame and guilt. These socially related emotions represent conflicts with oneself and depression. The association of social stress, trauma, and depression has been shown across cultures and societies. For example, during a twelve-month period women in Zimbabwe had an 87 percent burden of stressful life events, and 30 percent reported simultaneous depression. At the other extreme, women in rural Basque reported no stressful life events and had a 2.5 percent prevalence rate for depression (Brown, 1998). The bottom line is that acute stress, especially if it involves humiliating, socially rejecting, entrapping feelings, is causally related to depression (Maletic & Raison, 2017).

Scott felt rejected, depressed, and ill at the same time. As noted earlier, social withdrawal protects others from our illness, and it is part of the constellation of symptoms of sickness behavior. Our capacity to form and maintain relationships has been fundamental to our evolution, development through the life cycle, and health. It is therefore no surprise that poor-quality or no relationships can have a devastating effect on mood. Just as being rejected, ostracized, abandoned, or isolated could have meant death to our hunter-gatherer ancestors—and suffering these major stressors as ACEs during development often results in multiple ill health consequences—so do they at any point during the life cycle result in anxiety and/or depression.

The ACC is involved in detecting social pain and physical pain (Muller-Pinzler, Krach, Kramer, & Paulus, 2016). The dorsal (top) portion of the ACC is sensitive to social rejection. Ill health can also sensitize the dorsal ACC, via PICs contributing to social anxiety. In other words, when ill we tend to feel rejected by others and depressed.

The ACC is positioned at the intersection of dopamine neurons, periaqueductal gray, hypothalamic, and amygdala circuits, making it crucial for the detection and regulation of arousal and drive. This makes the ACC important for instigating adaptive responses to negative emotional stimuli such as anxiety and depression. It serves as an important switch to either engage the fight-or-flight response or enhance the sensitivity between the salience and executive networks to bodily distress signals (Maleic & Raison, 2017).

Revolving Internal Conflict

Both Annie and Scott had been feeling paralyzed by indecision, not knowing what to do to get out of their depressive rut. They felt like their circuits were jammed. Accordingly, depressed people tend to not activate the ACC or to shut it down in the face of difficult situations. The ACC is a monitoring system that activates when we face uncertain situations or demands that may have multiple interpretations, some of which potentially could go wrong. Active during conflicts, ambiguous situations, and consciously experienced feelings, it is important to help negotiate difficult situations. The ACC is chronically underactive among depressed people, and its activity increases when depression lifts.

The cognitive and affect regulatory deficits with depression are associated with reductions in the following:

- Neuronal densities in the dorsolateral PFC

- The ventral PFC

- The ACC

Abnormal ACC functioning has been one of the central neuropathic correlates of depression. The dorsal ACC has generous connections with the dorsolateral PFC, and so executive network functions such as working memory and decision making suffers. In contrast, the rostral/ventral (bottom) part of the ACC is involved in emotions and is preferentially connected to the amygdala and so with threat detection (Davison et al., 2002). Sadness overactivates the ventral ACC, the amygdala, and the insula, reducing of activity in the dorsal ACC and dorsolateral PFC.

Depressed people tend to get lost in negative ruminations, brooding, gloomy autobiographical memories, and depressive feeling states, leading to hopelessness. These tendencies reflect reductions in the dorsolateral PFC and ACC that strengthen connections between the salience network and the default-mode network at the expense of the executive network (Maletic & Raison, 2017).

The Depression Switch

Seriously depressed people tend to have excessive activity in the ventral ACC. Increased metabolism, increased blood flow, and reduced volume of the ventral ACC have been associated with depression, in step with the intensity of sadness (Mayberg et al., 1999). The area adjacent to the ventral ACC (referred to as Brodmann area 25) has been referred to as a “depression switch” because of its bridge between attention and emotion. The improvement of depression is associated with a reduction in activity in the ventral ACC, insula, and orbitofrontal cortex, with corresponding increases in the dorsolateral PFC, hippocampus, and dorsal ACC (Mayberg et al., 2005; Goldapple et al., 2004). When depression is successfully treated, these areas tend to show increases in hippocampus and ACC, with a concommital decrease in rumination and increase in optimism (Sharot, Riccardi, Raio, & Phelps, 2007).

Our ability to detect and correct errors is essential for our mental health. The ACC is critical for error correction and to cognitively resolve errors. Cognitive reappraisal involves recognizing the negative pattern your thoughts have fallen into, and changing that pattern to one that is more effective. Detecting errors is generally excessive for people with depression, and Scott’s therapy addressed these overly critical tendencies so that he was better able to make decisions and engage in behaviors without second-guessing himself. Successful reappraisal is associated with increased activation of the ventral lateral PFC and the nucleus accumbens (Wager, Davidson, Hughes, Lindquist, & Ochsner, 2008). However, a one-dimensional reappraisal has limited value and durability, such that reappraising his situation with the narrative that he “will hold together until Annie recovers” was tested quickly and failed. By co-constructing a broader range of meaning and feeling, his reappraisals address his stress and depression head on instead of with his usual avoidance.

Approach Versus Avoidance

The secret of getting ahead is getting started.

—Mark Twain

Scott’s increasing avoidance of peers at work and his family had been painting him into a depressive and anxious corner. While avoidant and withdrawal behaviors are associated with the overactivation of the right hemisphere, approach behaviors are associated with the left hemisphere. Accordingly, depression is associated with a deactivation of the left PFC and the motivation circuit. The most vivid example of the effect of this asymmetry is illustrated by patients with a left-side stroke, making the right hemisphere dominant. They become extremely depressed and may wonder why they should make the effort to go on living. In contrast, those with a right-side stroke, which makes the left hemisphere dominant, show a laissez-faire attitude, demonstrating more acceptance of their condition, and may regard the stroke as merely an inconvenience. The bottom line is that avoidance and withdrawal contribute to depression and that engaging in life with constructive behavior diminishes depression.

Regions of each side of the PFC contribute differently to behavior and affect: the right dorsolateral PFC is associated with avoidance/withdrawal behaviors, while the left dorsolateral PFC is associated with approach behaviors, and the right orbitofrontal is associated with negative emotions, while the left orbitofrontal cortex is associated with positive emotions.

Because Scott tended to be overwhelmed by a global perspective and withdrew from others, he overactivated his right hemisphere, which resulted in more negative emotions. To rebalance the ratio of activity between the two hemispheres, I encouraged him to construct short-term goals that were described with a positive narrative and to engage in accomplishing these goals. All these promoted a “can do” attitude and positive emotions, boosting activity in his left hemisphere.

Because it is much easier to agree that taking action is necessary than actually doing so, therapy with Annie and Scott needed to address their motivation. To put the importance of behavioral effort in perspective, I have often used the analogy of starting a car that has lost its starter. To start my semi-electric Volt, I merely press the start button. But if the starter is out, the button does nothing. Similarly, having an insightful thought is not enough to start up motivation to lift out of depression. The biological factors contributing to depression are too strong to be reversed by thought alone. I once owned a 1967 VW squareback that had a manual transmission, and on a trip to the Rockies in Colorado my starter broke. I was able to start the car anyway by parking on a hill or having friends push me while I sat in the car with my foot on the clutch peddle and the transmission “in gear.” After reaching 5 miles per hour I popped the clutch and the car started. Climbing out of depression, especially for Annie, necessitated this kind of approach. No insightful thought was enough to kindle motivation. Her motivational circuit needed to be primed much like my VW needed to be pushed. Because this circuit is essentially the habit circuit, motivation needs a push start to develop the neuroplasticity to create positive and mood-enhancing habits.

As described in Chapter 6, the nucleus accumbens, striatum, and the amygdala are in close proximity, and together they play a significant role in the motivational system. The nucleus accumbens is a peanut-size structure positioned deep within the salience network, between the striatum and amygdala. Because the striatum is involved in habits and movement, while the amygdala is involved in relevance detection, this habit circuit provides an interface between pleasure, emotions, and our actions. With executive network connections within the dorsolateral PFC controlling problem solving and planning, kindling motivation combines decision making with movement and follow-through.

Prior to therapy Annie failed to engage in rewarding activities; consequently, there was less activity in her nucleus accumbens, which resulted in a corresponding loss of pleasure. She became anhedonic, in part because her accumbens was deactivated. When she failed to move her body, there was a drop in activity in her striatum, which resulted in sluggish movement. And when she was less attentive to the here-and-now and engaged in less planning for the future, there was a drop in the activity in her PFC, resulting in poor concentration, which she described as “brain fog.”

The effort to reestablish pleasurable activities has been a staple therapeutic approach for depression for over forty years, referred to as the behavior activation technique within cognitive behavioral therapy. Annie was encouraged to engage in pleasant activities. By monitoring her mood during these activities, she grasped the connection between behavior, cognition, and emotion.

Annie’s motivation was primed by the interactions between her nucleus accumbens and incoming sensory information to evaluate emotional memory by her PFC as to whether to “go” with a healthy behavior. When she felt that a behavior resulted in a positive outcome, she strengthened those synapses mediated by dopamine, and her motivation increased to engage in that behavior again.

This neural circuit, also referred to as the effort-driven reward circuit, underlies why the behavior activation technique helps lift depression (Lambert, 2008). When the nucleus accumbens, the striatum, and the PFC were simultaneously activated, this kindles a positive mood. When the nucleus accumbens was activated by dopamine, Annie anticipated pleasure and was more motivated try to replicate the behavior again. The striatum-driven movement toward the positive habit and her PFC-generated executive functions of planning orchestrated her motivation to continue.

The motivation circuit connected her movement, emotion, and thinking, which helped lift her from depression. Because kindling these neural circuits necessitated use and follow-through, engaging incrementally in productive activities raised the levels of dopamine and serotonin, resulting in increased positive feelings, and allowed her to reap rewards of her productive behavior, boosting her sense of self-control, and self-esteem.

It is common that depressed clients do not know where to start. They can be informed that they can rev up their brain circuits to lift depression by doing the things they don’t feel like doing. Just by planning activities they kindle the PFC. Then when they move to perform the activity the striatum activates. And finally the nucleus accumbens activates when they feels the anticipation of pleasure of doing it again. Activated all together they can lift themselves out of depression.

REBALANCING THE MENTAL NETWORKS

Bob complained that his wife and friends suggested that he needed to be evaluated for attention deficit disorder. He disagreed with their opinion but did acknowledge that “at times that I’m lost in thought and get a little down.” He added, “I just can’t get some things out of my mind.” Through his fifteen years in the Alcoholic Anonymous program he understood that he was “doing a lot of stinking thinking” related to events that took place when he was drinking. However, he argued that he was trying to come to terms with hurting and being hurt by his ex-wife.

Bob’s pattern of default-mode network (DMN) activity promoted depression. His “reflections” became increasingly laced with feelings of threat, anxiety, and hopelessness. Without participation of his executive network, these ruminations took on a life of their own, with less grounding in practical reality. Bob excessively drudged up self-recriminating memories with regret, remorse, and self-pity. It was not productive time, to say the least.

Hyperconnectivity of the DMN has been a consistent feature found in imagery studies that underlie the common symptoms of depression, including negative ruminations, brooding, and excessive self-referential thought. This hyperconnectivity is so powerful that it is evident in people who have recovered from major depression and may underlie their vulnerability to relapse (Nixon et al., 2014).

Responding less to external cues, Bob was rudderless and lost in a morose sea. With tendency to be “stuck” in himself at the expense of adapting to his environment, his depression was characterized by excessive coupling of the salience network with the DMN, producing ruminations on negative autobiographical memories and negative emotional states. His ruminative stewing hijacked his working memory and other executive network functions. The emotions generated from his salience network transformed into sadness, promoting the access of state-based depressive memories.

Somatic Grounding

People with major depression may tend to have less insula activity. In fact, insula hypoactivity has been considered a risk factor for depression (Liu et al., 2010). This suggests that those who are less in contact with their body tend to be more vulnerable to depression. In contrast, increased activity and volume of the insula are associated with the successful treatment of depression (Fitzgerald, Laird, Maller, & Daskalakis, 2008). Bob regarded himself as uncoordinated and “terrible at sports” as a child. Therapy entailed increasing his attention to somatic sensations.

Bob’s failure to flexibly engage and get his mental operating systems to work together disrupted the dynamic equilibrium between them and his mental health. When his salience network and DMN became coupled together, they minimized activity in his executive network, and he became lost in melancholy rumination and depressive emotions. He ruminated on what he had endured and felt more depressed because of it.

With depression there tends to be a short-circuiting between the salience network and the DMN that allows negatively valenced emotions to enter a reverberating ruminative loop (Maletic & Raison, 2017). This loop combines state-based negative memories of past failings and disappointments with depressive feeling states, brooding, and sulking. The cognitive blunting is more like smog than fog, breathing it in as toxic. Whereas excessive DMN activity is associated with depression, an increase in the executive network activity in problem solving helps navigate out of this depressive state.

Bob’s DMN increased when his dorsolateral PFC was not engaged, such as when he was bored, experienced no novelty, or was just tired. His obsessive ruminations took over, and he stewed over the negative experiences he had with his ex-wife. Helping him break out of his depressive ruminations involved strengthening his attention skills to orient to the present moment, to reflect on what was occurring around him.

Because breaking out of a depressive DMN spiral was difficult, Bob was encouraged to work toward making the ruminations fade with exercise, social activities, and mindfulness, all demanding a here-and-now focus. For example, he engaged his executive network when he was jogging, briskly walking in the park, or having a conversation—during these activities he was less likely to drift into his depressive ruminations.

Therapy brought balance to the mental operating networks. His salience network provided information about important changes about his body sensations in response to what was happening in the environment and encoded the flow of his emotions. His DMN helped him reflect on himself and others, to access autobiographical memories, and to plan for the future and fantasize about possible positive outcomes. And his executive network took the information into working memory, prioritized, problem solved, and maintained attention, and he followed through on practical goals, behaving adaptively.

Between the Extremes

Most people are about as happy as they make up their minds to be.

—Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln suffered from periodic depression before and during the Civil War. Though the war took a major toll on him, simultaneously he suffered the death of his son and the depression of his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln. Despite the effects of acute stress and depression, he was able to manage the epic national crisis, support Mary, and orchestrate the deliberation of the “Team of Rivals” in his cabinet. Perhaps it was his capacity to reconcile opposites that enabled him to transcend depression (O’Hanlan, 2017). Being able to integrate and appreciate what is between the opposites offers a method of escaping the rigidity that depression brings.

Lincoln’s ability to invite and then reconcile opposites offers an opportunity to transcend depression. Bob developed the capacity to hold in mind the shades of gray between the memory of the pain he caused in the past and his desire and effort to be a better person in the future. He transcended the black-and-white thinking, overgeneralizing, and catastrophizing that had contributed to his depression. The cognitive skills to cultivate and appreciate the shades of gray and ambiguity strengthened his resiliency and diminished his depressive ruminations in his DMN.

Depressed people who incur damage to their hippocampus tend to lose the ability to appreciate the shades of gray and complexity inherent in most situations by reacting in a black-and-white manner and overgeneralizing. These deficits are based on faulty “orthogonalization” of information that would normally ensure that encoding new patterns does not interfere with the old and remains separable. We can say that Lincoln was a master “orthogonalizer.” Normally, sufficient numbers of dentate gyrus neurons, made possible through neurogenesis, facilitate orthogonalization.

A significant percentage of chronically depressed people have explicit memory deficits. And many people with chronic depression and those who were previously depressed show hippocampal shrinkage in the range of 8–19 percent. Potential causes of the shrinkage include increases in cortisol; excess glutamate that saturates the NMDA receptors, resulting in excitoxicity; and blocked neurogenesis, which results in no regeneration of hippocampus.

Effective psychotherapeutic interventions improved the connections between Bob’s salience and the executive networks (Maleic & Raison, 2017). Meanwhile, meditation weakened the connections between his salience network and DMN while strengthening his executive network. Bob practiced mindfulness, maintaining nonjudgmental attention to the present moment, pulling himself out of the past, and noticing the subtleties in present. He worked on neutralizing ruminations through observation of what he was doing in the present moment. When he found himself drifting into ruminations, he brought himself back to the present moment to reflect on goal-directed behaviors. He discovered that he could not make up for the past but understood that he was responsible for the present.

As he practiced mindfulness, Bob attempted to maximize attention to the novelty in each moment. Given that his depression was kindled by his focus on the past, his here-and-now observations provided an antidote to his negativistic rumination. Mindfulness targeted his depression by neutralizing monotony with attention to subtle changes in his environment and cultivation of curiosity. Through affective labeling, he learned to say, “That’s a depressing thought,” rather than “That’s depressing.” As he built the capacity to decenter negativistic thoughts and feelings, he understood that momentary events were not permanent realities. Because he had often been on autopilot, teaching him to behave with intentionality helped establish here-and-now focus to break out of depressive automatic thoughts and behaviors.

Orchestrating a Broad Approach

Since immigrating to the United States, Lyudmila sought therapy in hopes of alleviating depression. She complained that her therapist had suggested interventions that she had already tried with her previous therapists. To each therapist she said, “I tried that and it didn’t work.” In fact, she had seen many therapists over the previous few years. None of them seemed helpful enough to get her out of the dark, overwhelming hole.

Because multiple factors can contribute to depression, therapy for Lyudmila necessitated a concerted effort of multiple and simultaneous interventions. Much like a conductor of a symphony orchestra, the integrated approach involved the simultaneous orchestration of multiple feedback loops. Because depression can result from multiple factors, it was imperative to apply simultaneous therapeutic interventions.

Promoting the functions of the left PFC by encouraging active behaviors, instead of the avoidant and withdrawal tendencies of the right PFC, helped balance out the set point, the relative ratio activation between the two hemispheres. Because negativistic and self-deprecating rumination was often part of her cognitive set, helping her switch off of the “depression switch” in the ACC by challenging her tendency toward self-criticism was an ongoing process.

Because many factors can contribute to depression, she needed to understand that she had to do all the things we talked about doing at once, to climb out of depression. Tempering the right PFC bias by activating the left PFC was achieved by encouraging her to engage in specific detail-oriented behaviors.

Interventions That Bolster Underactive Brain Areas

- Social engagement

- Practice aerobic exercise

- Attend to sleep hygiene

- Improve the diet, including omega-3 intake

- Use inquiry to counter mood-congruent bias in the hippocampus

- Rebalance the left/right PFC with details and activity

- Engage the motivation circuit with goal-directed behavior

- Use mindfulness to neutralize ruminations and monotony

I began this chapter by noting that depression does not represent a finite disorder related to a specific gene and etiology. Multiple feedback loops contribute to the array of symptoms we refer to as depression. So, too, do we need to address depression with a wide spectrum of simultaneous interventions.