TEN

Mind in Time

If you had faith even as small as a mustard seed, you could say to this mountain, “Move from here to there,” and it would move. Nothing would be impossible.

—Jesus

Cara wanted quick relief from feeling depressed, and she found it. She was so pleased with her primary care physician for putting her on an antidepressant that she called his nurse two days later to report that she felt “100 percent better!” The nurse sounded perplexed instead of pleased. Linda sighed and then asked, “What’s up? Are you so burnt out that you can’t feel good that your patients are getting better?”

The nurse responded, “Ah . . . of course . . . I’m happy to hear it.” But she still sounded vague. With a huff, Linda demanded to talk to her doctor. He soon called her to follow up. Linda asked, “Don’t you and your nurse want to know that I am feeling better?”

“Well, uh, she, uh,” he began. “Well, actually those medications generally don’t work until three to four weeks. But, we are so pleased that you . . . ”

“What do you mean?” Cara cut in. She grew quiet. Feeling immediately glum, her depression was back like an avalanche.

BELIEF, PLACEBOS, AND THE MIND

Expectations have a powerful effect on the outcome health care treatments. The placebo and nocebo effects represent the power of beliefs that a patient like Cara forms that she will either get better or get worse as a result of a particular intervention or medication. These effects have been studied extensively in medicine during the last forty years. Theoretical support for placebo effects have been an integral part of various schools of psychotherapy, especially hypnotherapy, psychosomatic medicine, and health psychology.

A placebo can be any therapy causing psychophysiological effects or used deliberately in a clinical situation, such as when the doctor knows that there is nothing pharmacologically active in the pills but hopes the patient will do better anyway. Or placebos can be included in treatment unintentionally when the doctor himself believes that the pills will be effective but is not aware that there is nothing of benefit in the pills. Most relevant to psychotherapy is that the placebo effect illustrates how beliefs can alleviate suffering and even change biology.

The early history of medicine may partly be a history of faith in a particular treatment resulting in placebo effects. Such treatments as lizard blood, crushed spiders, bear fat, fox lungs, blistering, plastering, leeches, and bleeding may have periodically had benefit through the placebo effect. While some herbs bought today at the local health food store do actually have some medicinal benefits, others have merely a placebo effect. The key is the patient’s faith, belief, and hope in the treatment.

Cara had not only expectation of benefit but also faith that her doctor had the competence to provide relief from her suffering. Her belief in the treatment was augmented by feeling cared for beyond what family and friends could provide. The combination of empathy and expertise generated faith in his treatment. But when he informed her that the medication would not have an effect for weeks, her expectations abruptly changed, and so did her mood. Had the nurse initially responded by saying, “We are so pleased!,” Cara’s expectations and mood probably would have been quite different.

The following characteristics of a health care provider tend to increase the placebo effect:

- Good listening skills

- Empathetic attention

- Gaze attunement

- Appropriate touch

- Matching communication style (language and prosody)

- Welcoming physical appearance

- Close physical proximity

- Asymmetrical power dynamics between health care provider and patient (based on Kradin, 2008)

Incidence of a placebo response ranges from 10 percent to 70 percent, with effect averages of 35 percent (Kradin, 2008). The evidence suggests that placebos work best for subjective outcomes like pain. Placebos can be about half as effective as injection of morphine for pain reduction. When people feel that a particular medical intervention will hurt them less if pain relievers are applied, they will generally report less pain. For example, researchers applied a fake analgesic cream to two groups of people. Both groups had their forearms heated to a painful level. One group was told that they received an analgesic cream. The other group was told no medication was in it. The group that was told they had the medicated cream reported relatively less pain (Wager et al., 2004). There is also some evidence for efficacy in objective conditions (ulcers, angina), and positive placebo effects have been shown for insomnia, pain, and depression (Benedetti, 2008).

Cara experienced a type of placebo effect that reveals much about the major shift in mental health treatment. Over thirty years ago cracks began to show up in the foundation of the medical model in psychiatry, in part, because the placebo effect was revealed in a variety of studies for the efficacy of antidepressant medications. For example, a meta-analysis of three thousand patients who received antidepressant medication, psychotherapy, a placebo, or no treatment found that 27 percent of the therapeutic response was attributed to drug activities and 50 percent to the psychological factors surrounding the administration of the drug, which were unrelated to pharmacological activity (Sapirstein & Kirsh, 1988).

The placebo effect is indeed partly “in the head,” as revealed by changes in brain activity apparent in several imaging studies. We may speculate that Cara’s placebo response was consistent with responses of patients who received a placebo and were observed in brain imaging studies to show changes similar to those of patients who received Prozac (Mayberg et al., 2002). The placebo group, like the Prozac group, activated their prefrontal cortex, posterior insula, and posterior cingulate, with decreased activity in their hypothalamus, thalamus, and parahippocampus.

Studies have shown that people who believe that they are receiving a pain killer release endogenous opioids in their brains and, accordingly, report less pain. As an illustration of the role of endogenous opioids in the placebo effect, when they received opioid-blocking drugs, such as naloxone, they no longer reported pain reduction. Expectation also plays a major role in the placebo effect: when people are told that they are receiving a pain killer, dopamine is released in the nucleus accumbens as they anticipate relief from pain (Scott et al., 2007).

Placebo-Nocebo: Two Sides of Belief

The flip side of the placebo effect is the so-called nocebo effect: the negative effects from a placebo. Upward of 25 percent of patients receiving a placebo report adverse side effects, with 7 percent reporting headaches, 5 percent somnolence, 4 percent weakness, and 1 percent nausea and dizziness (Kradin, 2008). Whether positive or negative, the placebo response can be understood as a dramatic shift in the mind-body. For a nocebo response, mind-body systems self-organize away from an attractor governing homeostatic normality, while for a placebo response the movement is back to its previously established attractor of homeostatic normality (Kradin, 2008). The term attractor, borrowed from nonlinear dynamical systems, is a property of complex adaptive systems to explain how new order emerges from chaotic conditions. Some have suggested that we rename the placebo response the “meaning response” (Moerman, 2002). The meaning of a placebo or nocebo can be considered the attractor.

Like positive placebo effects, nocebo effects have also been identified with specific brain areas associated with pain, including the anterior cingulate cortex and insula, key parts of the salience network. Our anticipation of pain—in other words, expecting to receive a painful stimulus and what to do about it—plays a role in the perception of the pain by the prefrontal cortex through its gating and filtering of sensory information (Koyama, McHaffie, Laurienti, & Coghill, 2005).

Because expectation frames perception, the belief in psychotherapy can have major effects on outcome. In Ericksonian hypnosis the “expectancy set” had been understood as a powerful ingredient for positive outcome. Forty years ago, while giving a grand rounds talk at the University of New Mexico, Jerome Frank, psychotherapy researcher and author of the Power of Persuasion, hypothesized that one of the most powerful variables to psychotherapy benefit was the client’s expectation of relief of suffering. I looked around the room at the psychiatric residents as they scratched their heads. One of them chirped up incredulously, “If what we are doing can be boiled down to influencing the patient’s belief that he will get better, then what’s the point of our training in psychotherapy techniques?” To that Frank promptly replied, “You’re here to gain confidence and then exude it to your patients.” He went on to say that psychotherapy is garnered with many rituals and socially agreed upon expectations that something special will happen. To drive home that point, our offices are anointed with degrees hanging on the wall, sessions last fifty minutes, and as therapists we exude empathetic confidence. All these contextual specifics and meaning-making distinctions ec effect of the particular therapeutic technique employed. Had Cara been embedded in a society that believed that prayer, sand painting, or ritual dance were curative, her faith in one of those interventions would have influenced her recovery.

Yet, belief alone is not enough. Top-down and bottom-up processes interact. If Cara believed that she was receiving a medication that would not work until three to four weeks, she may have endured that much time before responding positively. Though her belief influenced the efficacy of the medication, it did not completely determine the outcome. She may have experienced some, a lot, or no relief, influenced not only by her belief but also a variety of other mind-brain-gene feedback loops, as described throughout this book.

The placebo effect demonstrates how the mind self-organizes felt meaning down to biological levels. Not merely a top-down causation, the placebo also represents constructed meaning emergent from bottom-up sensations. After Cara’s conversations with her nurse and doctor, she began to notice a variety of side effects from the antidepressant, of which she had been previously warned. Because the sensations were called side effects, she believed that the medication must be slowly working. In response, she felt less depressed. Was this reaction, too, a placebo effect? It may have been a combination of both placebo and medication.

The point is that placebo effects work through interactions with multiple social and biological factors. Top-down belief and bottom-up biological processes interact to contribute to outcome. Belief alone does not determine mental health, but it is an indispensable factor.

The greater the number of reasons to believe in the effect of psychotherapy, the greater likelihood that the client will experience a positive outcome. In other words, the more the client believes that there are biopsychosocial factors, including genetic, immune, brain activity, and cultural, that provide evidence-based scientific support for the interventions, the better the outcome. While modifying one belief factor may produce a ripple effect, changing others, the shear critical mass of multiple factors combined produces long-lasting mental health.

Attitude and Positive Psychology

I am fundamentally an optimist. Part of being optimistic is keeping one’s head pointed toward the sun, one’s feet moving forward. There were many dark moments when my faith in humanity was sorely tested, but I would not and could not give myself up to despair.

—Nelson Mandela

Taylor moved to the Bay Area, enticed by a lucrative job offer to join one of the tech giants of Silicon Valley. As a software engineer, he perfected algorithms that no one else had, making him a valuable commodity in an intensely competitive field. Initially, the job brought him a great deal of satisfaction and pride, buoyed by praise from management and peers. He found himself trying to fit in with his peers, emulating them by buying a $100,000 car, eating in high-end restaurants, and consuming only the finest wines.

To his dismay, the glow of the new job and environment soon faded. He thought his success would impress his father, but like everything else he had accomplished, it was never enough in his father’s eyes. He and his wife bought a house high above Los Gatos with a spectacular view of the bay on one side and redwood forest on the other. That did not impress his father, either.

The novelty was gone as he established what he called a “monotonous” routine at work. He became convinced that his vacations to Paris, Bali, and the Seychelles Islands, all to five-star hotels, were essential for “downtime.” But even the luxury and pampering began to wear thin. He expected the same level of extreme gratification from everything and everybody. His dopamine pathways had become tired. Prompted by what he considered a hollowness to his life, he shifted to wanting without liking and was left feeling empty yet wanting more.

Having habituated to an exceedingly comfortable lifestyle, a stable nuclear family without challenges, and a job that eventually demanded little of him but paid enormously well, he took for granted his life situation and wanted more. More of what, he wasn’t sure, but it seemed like “something was missing.” Dissatisfied with emptiness, he began seeing a therapist to discover the “right diagnosis.” Had he seen a therapist embracing the archaic medical model, the diagnosis might have been depression, followed by medication. But he was fortunate to see one of our postdoctoral psychology residents, Sara, who was well schooled in the neuroscience of the pleasure pathways and combining it with research in positive psychology. She was especially familiar with the research on life satisfaction, known in the popular press as happiness.

Positive Psychology Has Deep Theoretical Roots

The paradox of happiness was described by Taoist philosopher Chang Tzu (350 BC), who said, “You will never find happiness until you stop looking for it.” More recently, the fleeting and unexpected moments of life satisfaction have been described as “stumbling on happiness” (Gilbert, 2007). What is new is that research has been applied to the theory. Attitudes have been associated with different emotional outcomes.

To Taylor’s initial dismay, Sara suggested that he work on cultivating the capacity to practice gratitude. He told her that she must be “stuck, just like everyone else, on the idea that wealth and happiness were the same thing. How trite!” But the so-called global happiness reports have consistently shown that wealth alone does not buy happiness. In fact, lotto winners generally gravitate back to their earlier mode of functioning after the initial glow of their new-found riches wears off. Like a Lotto winner, Taylor found himself back to self-criticism, the echo from his father, right where he started prior to taking the lucrative new job. Like a drug, his lavish lifestyle exhausted his sense of satisfaction. He felt as if his chance of happiness was flushed down Donald Trump’s gold-plated toilet.

Researched Positive Attitudes and Behaviors

- Gratitude

- Compassion

- Acceptance

- Optimism

- Forgiveness

Taylor maintained that the real issue for him was that his father’s message that he was never good enough meant that “enough is never enough.” The truth was that his father did not feel good enough. In short, the misery was his father’s emptiness, which didn’t have to be shared with Taylor. Feeling less responsible for his father’s feelings took time. One session was canceled when his wife had the flu. She was not completely recovered when he returned. He complained that without her usual expression of warmth and playfulness he felt at a loss. Certainly he was a beneficiary but also he enjoyed seeing her contentment. He said that she had the ability to be satisfied and grateful wherever they were.

At the most basic level, the pivot toward gratitude began for him as a simple expression of the thankfulness for her recovery. By widening his scope and practicing gratitude, he focused on how she directed his attention to seemingly simple things that brought him satisfaction. While on the one hand he had previously taken for granted his wife’s “no strings attached” generosity, on the other hand he had fixated on his father’s insatiable selfishness. He realized that he had been pouring his efforts down his father’s empty drain and taking his wife for granted. With that spark in gratitude for his wife, their relationship shifted. He slowly directed his attention to those people that he had taken for granted. He developed a habit of starting the day by reminding himself of how lucky he was not for his wealth but for his opportunity to use it for social purpose.

Gratitude and Its Benefits

- Highly grateful people compared to their counterparts tend to experience greater life satisfaction and hope (McCullough, Emmons, & Tsang, 2002).

- They also tend to embrace a sense of spirituality, a belief that all things are connected. The combination of mindful focusing on the area around the heart and intentionally expressing gratitude has been reported to enhance positive emotional states (McGraty & Childre, 2004).

- Gratitude and positive emotional states correlate with relatively more activation of the left prefrontal cortex), anterior cingulate cortex, and pregenual anterior cingulate (Fox, et al.,2015).

Sara was able to tap into Taylor’s capacity to be playful that he enjoyed with his wife as a conduit to express generosity and compassion for others. Because he had far more than enough wealth for his family, he slowly learned that the cliché “giving is receiving” did not simply reflect empty platitudes. One of his new hobbies was finding ways to benefit the community as an anonymous benefactor. Just before Christmas he found out where his company’s janitors lived and delivered presents to their homes. Not wanting any direct credit for his generosity, he put the presents on their front porches, rang the doorbell, and then ran to hide in the bushes across the street, watching to ensure they answered the door and found the presents. He also stopped going to five-star restaurants and resorts. Instead, he started traveling to third-world countries for a “reality check,” ensuring all the while not to behave like an entitled tourist.

Mental Health Benefits of Promoting Gratitude

- Diminished depression

- Diminished anxiety

- Diminished stress

- Increased joy

- Increased enthusiasm

- Increased optimism

- Increased well-being

- Increased life satisfaction

Overall health improves, including enhanced sleep, more exercise, and lower blood pressure.

The prosocial benefits of gratitude include enhancements to romantic relationships, increased social bonds, and the tendency to volunteer more.

By expressing generosity and kindness to others, Taylor promoted positive feedback loops within his relationships, at work, in friendships, and in his marriage. Kindness to others promotes psychological benefits for the giver, including diminished depression, anxiety, and addiction. We can hypothesize that his acts of kindness produced a “helper’s high.”

Brain Areas Associated With Generosity

- Pleasure centers his brain (Moll, et al., 2006)

- Inferior parietal cortex (Weng, 2013)

- Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Weng, 2013)

- Vagus nerve (Steller, et al., , 2015)

These rewards stem from the dopaminergic reward system. A positive emotion “family tree” has been recently proposed, with an array of neurotransmitters stemming from enthusiasm (Shiota et al., 2017). Though emotions cannot be reduced to specific neurotransmitters or hormones, the concept of a spectrum of positive emotions associated with enthusiasm is attractive.

The Dopamine Reward System and Enthusiasm

- Serotonin: pride

- Testosterone: sexual desire

- Oxytocin: nurturant love and contentment

- Cannabinoids: awe and amusement

- Opioids: attachment, gratitude, and pleasure

ACTION-ORIENTED EMPATHY

Cultivating compassion and warm-heartedness for others shifts attention away from narrow interests and suffering (Dalai Lama, 2012). Compassion arises from empathy, as feeling with someone. It is not only wishing to see the person relieved of suffering but also the willingness to do something about it. This distinction describes an essential aspect of psychotherapy because therapists are best at forming an alliance when we express compassion.

Psychodynamic, attachment, and Rogerian theorists have long maintained that when clients feel felt uncritically, they can generate self-compassion. The neurophysiology underlying this feedback loop may involve the anterior cingulate cortex, which is associated with empathy. Expressing compassion generated a positive feedback loop for Taylor, by kindling compassion for himself. Instead of criticizing and judging himself, Taylor took a balanced approach to negative emotions, neither suppressed nor exaggerated, by a willingness to nonjudgmentally accept and acknowledge his humanity.

With self-compassion, the key is the enhancement of self-kindness (Neff, 2011). By doing his best to confront challenges, Taylor behaved in accordance to Reinhold Niebuhr’s Serenity Prayer, making a realistic effort each day on what he could do and not wasting energy on trying to do what could not be done, such as pleasing his father. Without this balanced effort, there was always the potential for self-criticism, consistent with a core belief conveyed by his father that he was unworthy. By acknowledging that perfection was not possible, he could make his best effort, and that was “good enough.”

Self-criticism is associated with relatively greater activation of the amygdala, right prefrontal cortex, higher cortisol, and increases of adrenaline, as well as with decreased performance and decision making and less resilience following setbacks. Self-compassion is associated with activation of the left prefrontal cortex, insula, decreased cortisol, and increased oxytocin, with clarity of thought and resiliency (Neff, 2011). Self-compassion is by nature antithetical to narcissism, with benefits to relationships embodied by compassion.

The Benefits of Self-Compassion

- Psychological, such as lower rates of depression, anxiety, recovery from posttraumatic stress disorder, and eating disorders

- Physical, such as alleviating chronic pain, improved lower back pain, and reduced inflammatory response

Self-compassion provided the successful integration of self-referential information to project Taylor into the future with an optimistic bias. The connections between his default-mode and executive networks mobilized his attention and working memory to support a positive stream of thought through the loop between his dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and hippocampus. When he reflected on his past, accessing a library of recent episodes and autobiographical memories to plan for a meaningful future, he moderated the feelings generated by his salience network. These loops operating in his mental networks co-constructed new meaning that embraced gratitude, compassion, and optimism.

Prior to cultivating gratitude, compassion, and forgiveness, Taylor had described himself as fundamentally a pessimist. Yet, he discovered that his old motto, “No good deed goes unpunished,” boxed him into an odd form of self-punishment. Whereas pessimism is a retreat, optimism is lean-forward attitude.

The Neuroscience of Optimism

- Increased left prefrontal activation, associated with approach behaviors and positive emotions (Fox, 2013)

- Increased orbitofrontal cortex activation, associated increased resiliency (Dolcos, 2016)

- Enhanced emotion regulation, associated with decreased anxiety and decreased amygdala activation

CONTEMPLATIVE ATTENTION

Ryan had seen a variety of therapists to deal with intermittent bouts of stress and a mix of generalized anxiety and dysthymia. He “never seemed to find the time” to follow through with the lifestyle changes that they recommended. Then a friend invited him to an evening talk on mindfulness, and he was sold. He told his friend, “Who needs all that diet and exercise stuff? If I just give myself a fifteen-minute mindfulness break during my hectic day, and I’m good, right?”

His friend rolled his eyes. “It sounds like if McDonalds had a mindfulness drive-through lane you would think that was enough.”

“That’s a great idea!” he responded, missing the point.

How does meditation enhance mental health? And how do these practices relate to positive psychology? Despite the recent hype, methods of quiet contemplation, prayer, and meditation have been practiced for at least two thousand of years. Why has there been a consistent tradition? In fact, prior to the emergence of the major theologies, hunter-gatherer societies had shamans, medicine men and women, curanderos, and so on, who may have practiced trance induction, during which they found reverence for their existence. With the advent of the major sociotheological systems twenty-five hundred years ago, contemplative practices were codified into conceptual frames that reflected their host societies (Arden, 1998).

The long history of contemplative meditation in the Christian tradition was practiced with the Desert Fathers in the third century, Saint Augustine and his focus on “the eye of the heart,” the Medieval Christian mystics (including Meister Eckhart, Saint Teresa of Avila, and Saint John of the Cross), the monastic orders, and more recently Thomas Merton, who began as a Trappist monk and became an insightful synthesizer of Buddhism and Taoism within the Christian tradition. While the term meditation has only recently become popular in Christian circles, the more traditional terms were contemplation and contemplative prayer. In his book Christian Meditation (2005), James Finley, a one-time student of Merton’s, outlined methods of meditation, including sitting still and upright, eyes closed or lowered, focusing on slow, deep breathing and nonjudgmental compassion. These methods are consistent with those practiced in the East.

Millions of people within the Alcoholics and Narcotics Anonymous programs have been transformed not only through sobriety and social support but also through the belief in a “higher power.” At the heart of all major theologies and their respective contemplative practices is the cultivation of meta-awareness, which promotes a soothing sense of security and transcendence.

Over four decades ago, to discover common threads among these methods, I woke before sunrise to meditate in the ashram next door; then, during a year-long trip circling of the globe through Asia, the Middle East, and Europe, I stayed briefly in different religious communes and ashrams, conversing with religious devotees, monks, and priests about their practices. Later studying and then practicing hypnotherapy further reinforced my belief that among all these practices are common factors that promote mental health. The theologically based beliefs, consistent with positive psychology, all seem to cultivate compassion and the belief in interdependence. There are several common methods: hypnosis, contemplative meditation, prayer, and relaxation exercises.

The following factors are common to prayer, meditation, relaxation exercises, and hypnosis. They are calming while reducing the troubling symptoms of psychological disorders and chronic health conditions.

- Deep, gentle, and focused breathing to slow the heartbeat and provide an accessible focal point for attention. The emphasis is on the exhale, emphasizing pressure on the diaphragm, which is associated with stimulating the vagus and the parasympathetic nervous system.

- Shifting attention to the here-and-now, to activate the prefrontal cortex, which calms overreactivity of the amygdala. With a focus on the present moment, the amount of time spent ruminating about the past and worrying about the future shrinks.

- A nonjudgmental attitude helps shift away from rigid expectations to flexible acceptance of whatever occurs.

- Observing body sensations and thoughts allows detachment from pain or general discomfort while simultaneously not denying its existence.

- Labeling anxious and depressing thoughts allows detachment of the thoughts from the emotions.

- A relaxed posture can dissolve body tension, which can be achieved by stretching through traditional yoga or a hybrid yoga.

- A quiet environment provides an opportunity to learn how to relax without distractions.

Contemplative Attention and the Mind’s Operating Systems

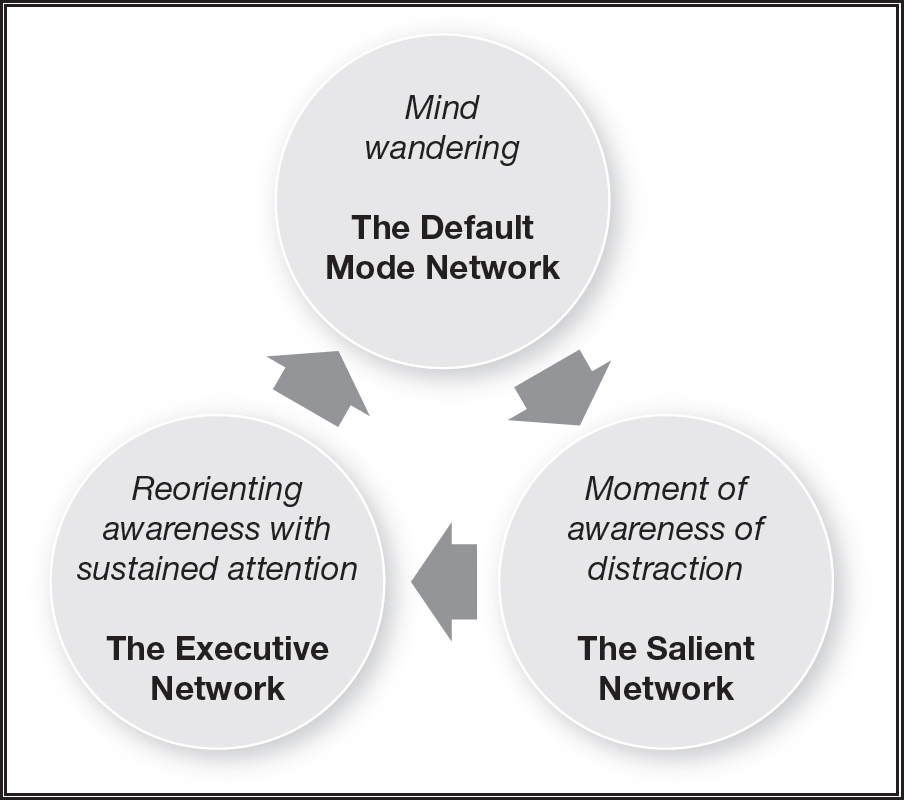

Meditation, hypnosis, and contemplation can be thought of as attentional methods of orchestrating the balance among the mental networks. Overall, meditation improves attentional flexibility, as the practitioner is less likely to get caught in repetitious ruminative thoughts (Slagter et al., 2007). Like hypnosis, during meditation one disengages attention to fixed narratives generated by excessive default-mode network activity and instead with the executive network promotes nonjudgmental awareness of thoughts, sensations, and emotions as they arise and drift away.

The executive network is critical to the moment-to-moment monitoring of experience during meditation. With the salience network’s contribution to subjective awareness of body and emotional feeling states to executive network’s attention to decision making and working memory, the variety of mental operating networks training methodologies can be collectively considered as means of contemplative attention. The focus on the breath, a word, or a phrase include broadening the attentional field to observe without judgement. The focused attention is on a calm non-reactive awareness of sensation, emotions, and thoughts as they arise and fade away.

In one study, two types of meditation practices were compared; Kundalini meditation, which involves breath manipulation and an emphasis on somatic awareness, and Tibetan meditation, which emphasizes open monitoring of moment-to-moment experiences. No differences were found between the meditation groups in heartbeat detection, but they both functioned better than for people in the control group who did not practice meditation (Lutz, Slagter, Dunne, & Davidson, 2008). Both meditation practices provide connectivity between the executive and salience networks through attention to somatic feeling states.

Figure 10.1: The contemplative experiences and the cycle of the activation of the mental operating networks.

The variety of styles of meditation involve different types of interactions between the mind’s operating networks. While the Vipassana tradition is characterized by open monitoring, with the practitioner nonjudgmentally observing moment-to-moment experiences, Zen meditation is characterized by sustained focused attention, such as on a chosen object (Lutz et al., 2008). The impact of meditation training on the activity of the default-mode network during a restful state increases the connectivity with the executive network (Taylor et al., 2013). Self-centered ruminations tend to dissipate with the functional impact of the enhanced connectivity with the default-mode network. With reduced connectivity between the default-mode network and the salience network and greater connectivity with the executive network, one makes less self-referential and emotional judgments based on the misfortunes of the past and instead is more aware of the adaptive potentialities in the future. This amounts to stepping into the future instead of holding on to the past. The greater awareness of the evolving present strengthens affect regulatory capacities while generating detachment from negative feeling states.

Meditation and the Mind’s Operating Networks

- The executive network provides a present focus and affect regulation.

- The default-mode network reflects on what we have learned about our place in the world by drawing on autobiographical memories and integrating them in the present moment through the aid of the executive network.

- The salience network allows us to feel ourselves within the world.

A recent study has revealed that creativity increases with the coactivation of the mental operating systems (Beaty, et al, 2018). Normally, the operating systems shift back in forth in their ratio of activity. As we have seen throughout this book, when one network dominates the potential for psychological disorders increases. The balancing of activity increases not only mental health but also creativity.

Contemplative Compassion

Because of the wide-ranging benefits to individuals and societies, the common denominators of all the major theologies, whether on the Judeo-Christian-Islamic spectrum, the Hindu-Jainist-Buddhist spectrum, and the Taoist-Confusionist-Buddhist spectrum, have been the importance of compassion (Arden, 1998). Whether for those in our immediate environment, communities, societies, or internationally, compassion involves leaning toward and expressing kindness. Each of these theologies promotes cultivation of compassion, practiced individually and collectively through contemplative prayer and meditation.

Christian contemplation has been described by Friar Richard Rohr as “the long, loving look at what really is. The essential element in this is time” (2015, pp. 88). The connection between contemplation and compassion is action. Rohr goes on to say, “The effect of contemplation is authentic action, and if contemplation doesn’t lead to genuine action, then it remains only self-preoccupation” (p. 121). The concept of compassionate engagement is embraced by all theologies. The emphasis is on action in time, as expressed the saying, “Zen is not like chopping wood. Zen is chopping wood.”

My old friend Lisa Leghorn personifies the practice of compassionate activism. In her teens and twenties she was involved with several feminist groups and helped establish one of the first domestic violence shelters in the United States. In her efforts to understand and address the causes of injustice toward women, she moved to Equatorial West Africa for two years to research the social supports for women’s economic power in those cultures. Once back in Boston and continuing these lines of inquiry for a book called Woman’s Worth, her conviction deepened that “economic justice did not go far enough,” that broad social transformation requires fundamental changes in consciousness. When I met her forty years ago in Santa Fe she was completing that book while working evenings for Georgia O’Keefe.

Through all these experiences Lisa was becoming increasingly angry and worn down. She explored a number of modalities, searching for ways that would simultaneously sustain herself through activism while making possible a profound change in consciousness she felt was needed. She met H. E. Chagdud Tulku Rinpoche, a Tibetan Buddhist meditation teacher who introduced her to methods for “uprooting negativity” and cultivating the mind’s capacity for positive mental habits. First becoming his student, then interpreter, she eventually was ordained by him as Lama Shenpen. She began to teach Bodhisattva peace trainings, where participants from a wide variety of religious backgrounds seeking methods to become more effective in benefiting others are taught to be aware of and transform what is repeated in their minds. Instead of “pushing the pause button” on negative thought patterns, they learn to change those habits to become more fully responsive to the needs of others. Lama Shenpen’s search had culminated in the practice of combining meditation, compassion, and activism.

One the methods of meditation she teaches in the Bodhisattva peace training is contemplation, similar to some Christian contemplative methods. First she contemplates compassion, then pauses, “relaxes,” and then returns again to contemplate compassion. This paring between the executive network’s working memory and attentional capacities and the default-mode network’s restful and reflective mode supports homeostatic balance among the operating networks. Contemplation without periodic rest may subtly increase stress. By working toward balance between contemplation and rest, meditation can become increasingly integrated and effortless. Through this rhythm between consuming and digesting, repetition and pacing, the goal is to cultivate compassion that is experiential rather than merely conceptual.

By factoring in self-compassion, contemplative meditation may help balance the interactions between the minds operating networks. One learns to nonjudgmentally observe negative memories and thoughts and to detach negative affect from the thoughts and memories to interrupt the rumination cycle.

Loving kindness meditation, sometimes called metta meditation, involves wishing others well and is associated with the following:

- Increased positive emotions (Frederickson et al., 2008)

- Increase positive feelings of social connection, associated with increased vagal tone (Kok, et al., 2013)

- Reduced migraines (Tonelli, & Wachholtz, 2014))

- Improved lower-back pain (Carson, 2005)

- Decreased symptoms of posttraumatic stress syndrome in veterans (Kearney, et al., 2013)

Meditation-Augmented Therapy

To what degree do meditative practices contribute to the mental health? With all the recent attention in either applying or combining meditation to psychotherapy, it is important to consider the factors that increase positive outcomes. Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) has been studied extensively for its utility in helping people with general and mental health problems. MBSR has been shown to reduce amygdala activity in people with social anxiety disorder (Goldin & Gross, 2010). Accordingly, it is associated with decreases in negative emotions and increases in attention-related neural networks.

Neural Correlates of Mediation

- Stress reduction through MBSR training has been correlated with incremental increases in antibody response (Davidson et al., 2009).

- MBSR training over time has been associated with reductions in gray matter densities in the right basolateral amygdala (Holzel et al., 2010).

- Long-term meditators show increased thickness of the medial prefrontal cortex and also enlargement of the right insula (Lazar et al., 2005). The medial prefrontal cortex has been associated with self-observation connected with mindfulness meditation (Cahn & Polich, 2006).

- Long-term meditation has been shown to increase thickness of the prefrontal cortex, which augments affect regulation, observance, and attention. The increased thickness of the right insula corresponds to heightened awareness of the mediator’s own body.

- Meditation has been associated with significant effects in neuroplasticity of the left prefrontal cortex and decreased amygdala response to stress (Davidson, et al., 2003).

- Memory and learning centers associated with the left hippocampus can change within eight weeks of practice (Holzel et al., 2011).

- With elevated activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and rostral anterior cingulate cortex with a corresponding decrease of amygdala activity and grey matter density, there are offsets to cortical thinning (Lazar, 2005).

- Mindfulness training is associated with greater left prefrontal cortex activation, stress reduction benefits, and increases in antibodies to influenza vaccine (Davidson et al., 2003).

One of the main common denominators among MBSR approaches involves moderating the stress response systems while activating the parasympathetic nervous system. Through activities such as yoga, meditation, and tai chi, improvements have been reported in mood and boosts the immune system have been measured by decreased production of interferon-gamma and increased production of interleukin-4, an anti-inflammatory cytokine, by stimulated T-cells (Carlson et al., 2003).

Since the late 1960s researchers and practitioners had been using biofeedback instruments to demonstrate how people attain deeper states of relaxation. More recently, there has been an intensified focus with neurofeedback instruments. Long-term meditation practitioners have been observed to produce marked increases in the brain’s electrical signals as measured in the fast-frequency oscillation referred to as gamma waves, particularly in the prefrontal cortex (Davidson et al., 2003). In contrast to the assumption that meditation is analogous to simple relaxation, the increase in gamma waves represents an increase in synchrony between the prefrontal cortex and other brain regions not associated with relaxation. Gamma and beta brain oscillations are associated with attention, perception, and learning. Synchronized activity that selects information for further processing has a much stronger impact on cells than temporarily uncoordinated activity associated with relaxation. Attention synchronization increases learning. A person may “learn” to be phobic and need to learn not to be phobic. Through relearning this new synchronized state rewires the brain. Meditation offers one of the many ways that can facilitate a new synchronized state that can augment psychotherapy to ameliorate anxiety and depression.

Mind-body programs have become a staple for many medical centers. Twenty years ago at Kaiser Permanente my mind-body class was one of many. Each of our twenty-four medical centers in Northern California had mindfulness classes. Because mind-body medicine has become mainstream, we are able to gain from large population studies throughout the world. For example, the effect on anxiety and depression was examined in a meta-analysis of 39 studies totaling 1,140 participants receiving mindfulness-based therapy for a range of conditions such as cancer, generalized anxiety disorder, and depression. The overall results indicated that mindfulness-based therapy was moderately effective for improving anxiety and mood symptoms (Hofmann, et al., 2010). Positive effects on anxiety, depression, and pain were found by a systematic study of 47 randomized controlled trials, with a total of 3,515 participants, but the effects were not superior to exercise, yoga, muscle relaxation, cognitive behavioral therapy, or medication (Goyal et al., 2014).

The effects of a variety of methods including tai chi, quigong, meditation, and yoga on the immune system were examined in comprehensive meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. The immune-system-related inflammatory outcomes indicated a moderate reduction of C-reactive protein, a small but nonsignificant reduction of interleukin-6, and no effect on tumor necrosis factor-α, immune factor CD4, or natural killer cell counts (Morgan, Irwin, Chung, & Wang, 2014). There were stronger effects from tai chi, quigong, and exercise compared to meditation, perhaps from the benefit of movement. In summary, mind-body therapies can influence some aspects of the immune system, including some inflammatory measures, but again, they are incomplete by themselves.

A “third wave” of cognitive behavioral therapy has included a mindfulness component. The most prominent of these include mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, and acceptance commitment therapy. These approaches teach people how to relate differently to their thoughts, feelings, and bodily sensations. Borrowing from Buddhism but not dissimilar to Christian contemplative methods, they promote accepting thoughts and feelings without judgment. Rather than trying to push the thoughts and feelings out of consciousness, a client may be able to indirectly reduce automatic and maladaptive reactions to thoughts, feelings, and events. The differences between these metacognitive models and traditional cognitive behavioral therapy approaches typify the following exchange: When depressed individuals say, “I am a bad and defective person,” cognitive behavioral therapists ask them to challenge the validity of that statement and develop alternative thoughts. In contrast, metacognitive-oriented therapists teach them to say: “I’m just having the thought that I’m a bad and defective person,” or “It is just a thought. It does not mean that I am in fact a bad person.” This slight change is meant to detach the thought from the emotion and reduce the destructive power of the negative thought. Labeling emotions to reduce anxiety and depression tends to inhibit tame the amygdala through the prefrontal cortex’s emotional regulation pathways.

Mindfulness-Augmented Therapy

The adoption of mindfulness-based approaches within these therapeutic modalities has been applied to specific disorders:

- Anxiety disorders, with acceptance commitment therapy (Hays & Strosahl, 2016)

- Borderline personality disorder, within the dialectical behavior therapy (Linehan, 1993)

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder, with mindfulness added to cognitive behavioral therapy (Baxter et al., 1992),

- Depression, with mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral therapy (Teasdale et al., 2000; Ma & Teasdale, 2004)

- General medical problems, such as chronic pain (Kabat-Zinn, 1982)

The practices of contemplative meditation and mindfulness attempt to look for novelty, subtle beauty, and satisfaction in each moment by activating attentional networks. This open focus strengthens the indirect dopamine pathways to inhibit impulsiveness while enlarging the scope of potential pleasurable experiences. With less impulsive habit-driven behaviors, one is better able to learn to appreciate the rich complexity of life. Instead of being disturbed ambiguity, one is fascinated by it. Much of the movement toward greater “self”-organization depends on the ability to sustain attention and appreciation for the subtleties of present moment.

THE “SELF”-ORGANIZING MIND

This book has explored the many feedback loops that contribute to mental health or ill health. The quest to find “the” factor that “causes” poor mental health or the “correct” therapy has led to dead ends. The belief in the pure essence of things, including our “core identity” as individuals, has faded as we have come to understand that DNA is not destiny (Heine, 2017). Research in epigenetics and psychoneuroimmunology has shown that genes can turn on or off and that disease processes and mental health are significantly related to our lifestyle and experience. Our brain and stress response systems adapt to our experiences. And our minds are influenced by all these interdependent systems, not a static self.

We use our mental operating networks to “self”-organize. As complex adaptive systems, we self-organize in time, neither staying completely the same nor changing completely. We can evolve and become progressively more adaptive and healthy or devolve and become ill. Time, and ourselves within it, does not stand still. Healthy minds adapt to changing environments and create situations that promote health.

Feelings play a role in the awareness of time, self, and the global emotional moment of subjective time. This subjective awareness feedback loop “self”-organizes increasing scales in complexity of a sense of self. Rather than having a static sense of self, in therapy clients learn to identify perceptual feelings of themselves across time that contribute to the subjective awareness of a sense of “me” in the ongoing present moment.

Self-organization maximizes the flexible zone between stability and change. While too much stability causes rigidity and leads to depression, too much change is chaotic and leads to anxiety. Healthy ‘self”-organization is both self-referential for stability and adaptive so that we become something greater than we had been. The mind is a self-organizing emergent process that is both influenced by and influencing its subordinate factors (Arden, 1996; Siegel, 2017). Given that the mind is a self-organizing process, its self-recursive shaping of information contributes to “self”-organization of our evolving individuality, neither static and unchanging nor always in flux.

Complex adaptive systems, such as ourselves, are composed of multiple feedback loops. The more complex the feedback loops, the more complex the adaptive system’s ability to “look ahead” in time, examining the effects of various action sequences without executing actions.

As complex adaptive systems, we thrive with openness and flexibility, maintaining continuity though self-recursive self-organization. Healthy minds are not unconstrained by chaos or rigidity that impedes growth. Unconstrained chaos in psychological terms represents anxiety, so that the person who feels out of control, activating stress systems when there is no real danger. A depressed person’s rigidity, being stuck in the past, ruminating over negative events in his life, holds onto the same negativistic story line and cultivates a depressed mood. When healthy, we are flexible and adaptable and can deal with near chaotic situations by maintaining internal stability and continuity.

Because we are complex adaptive systems, we are part of the environment (space) while adapting to our era (time). Though as Wittgenstein noted there are limitations of language, we may clumsily say that the brain is a noun (a substance) and that the mind is a verb (a process). Our minds, composed of mental operating networks and memory systems, adapt to the meanings we construct and so modify our brains and bodies.

As complex adaptive systems, the interactions among our subsystems (genes, immune systems, bodies, etc.) give rise to the emergent mental networks that represent the superordinate capacity to think, feel, sense, and behave in extraordinarily complex ways. We develop relationships with other minds with the same capacities, leading to more complex relationships within families, towns, cities, and societies. All those mutually interdependent factors self-organize through openness and nonlinearity.

The mind is an emergent “self”-organizing process that cannot be reduced to its constituent parts, its operating networks. It is profoundly influenced by all elements of the self—genes, immune and neural systems, family dynamics, and culture—and it influences each of these systems at various levels. From this point of view, the mind is a meaning-making process constructed from the nonlinear interactions among all of its contributing subsystems. Psychotherapy can help orchestrate these changes to promote a healthy mind-body by reintegrating the subsystems that had become dysregulated. Therapy must take into account that as complex systems we need to facilitate the flexible interaction among the mind’s operating networks. Within the relevant cultural framing and socioeconomic position, psychotherapy in the twenty-first century must address all these feedback loops.

In the one hundred years since the theologian and paleontologist Pierre Theilard de Chardin wrote The Phenomenon of Man, we have come to the point in evolution where we can understand the emergence of minds. In so doing, we are in a position to offer help to people whose minds work against them, in a far more integrated way than ever before. And so the practice of psychotherapy connects the domains that previously had been compartmentalized. The feedback loops within the mind-brain-gene continuum will continue to be articulated in the years to come, so that we can truly offer an integrated psychotherapy in the twenty-first century.