THE SIX (OR SO) PATRIARCHS

A SCROLL found in the Dunhuang cave library tells us that in about 475 C.E . a monk from southern India got off a boat in Guangzhou, China, a city once known in the West as Canton. Then as now it was a busy port on the Pearl River, which flows into the South China Sea.

The city was used to foreigners and also to Buddhist monks. As he walked through narrow streets filled with noisy vendors and the smells of crowds and cooking, the stranger probably attracted little attention. Yet this inauspicious moment would be commemorated in a famous koan: Why did Bodhidharma come from the West?

The traditional story of the birth of Zen begins with the arrival of Bodhidharma, who became known as the First Patriarch, in China, and continues through the lives of five more patriarchs. Each of these revered sages, the story goes, chose his best student to succeed him as patriarch of the lineage—a rite of passage marked by passing on the robe and bowl of Bodhidharma. This tradition ended with the sixth and last patriarch, Dajian Huineng, who died in 713.

As we’ll see in this chapter, this clear-cut tale of creation and succession is not the whole story of how Zen began. Many of the elements of practice and doctrine associated with Zen today made their way to China before Bodhidharma. Many other elements didn’t develop until long after the time of the patriarchs. And the exact moment Zen emerged as a distinctive school becomes more elusive the more you try to pin it down.

Madhyamaka teaches us that all phenomena are the result of ever-changing causes and conditions, without self-essence, and we identify them as particular things with particular names simply out of expedience. It’s good to keep in mind that the phenomenon called Zen Buddhism is no different.

Further, much of the tale of the Six Patriarchs, robe and bowl included, appears to be a post hoc invention of the seventh century that was superimposed over a much more complicated history. Framing early Zen history as simply about six particular men is a very artificial way to tell the story.

Nevertheless, the Six Patriarchs are so embedded in how Zen understands itself that it’s difficult to put that story aside. So it is a story I will tell. And, as is traditional, we’ll begin with Bodhidharma. To better understand the story of Bodhidharma, however, we need to begin by exploring the status of Buddhism in China at the beginning of the sixth century.

Early Chinese Buddhism

It’s believed Buddhism arrived in China in the first century C.E ., during the Han dynasty (206 B.C.E .–220 C.E .), a time of relative political stability. By the time Bodhidharma stepped onto a dock in Guangzhou, Buddhism had been in China for more than four centuries.

According to legend, one night the Emperor Ming of Han (28–75 C.E .) dreamed of a shining, flying god, and this somehow inspired him to invite two Buddhist monks to the Han court. It’s more likely that the first Buddhists in China were monks from Gandhara and Bactria who followed merchants on the Silk Road.

By the beginning of the second century, a few Buddhist communities had been established in China. It’s believed the first of these was in the Han capital of Luoyang, in present-day Henan Province. We will be returning to Luoyang frequently as we trace the story of early Zen.

By the end of the second century, Buddhism was popular enough that an official in central Jiangsu, near modern-day Shanghai, made a name for himself by erecting a Buddhist temple and sponsoring elaborate ritual bathings of a gilded Buddha. These acts of piety—plus the free food and drink offered at the ritual bathings—gave this official a large following. I regret to say that his subsequent career as a homicidal warlord called his sincerity into question.

At the beginning of the third century the period of stability was closing. Although the Han dynasty didn’t end officially until 220 C.E ., the empire had been crumbling into chaos for about forty years by then. The demise of the Han was followed by a bloody period in which China splintered and resplintered into multiple kingdoms—first three, then several more—that were often at war with each other. For our purposes, it isn’t necessary to go into all the details of the political fragmentation, except to say there was a lot of it. This phase of China’s long history was filled with epic battles, psychopathic warlords, and celebrated heroes, plus ever-shifting alliances and boundaries.

The most significant splintering was between north and south. At the beginning of the fourth century, northern China was invaded by five tribes of nomadic people from the west and north. Luoyang, by then the capital of the western Jin dynasty (265–316), fell to Xiongnu nomads in 311. It’s said that ten thousand of the city’s defenders were slaughtered in their final battle.

Another ancient city of significance, Chang’an (near today’s Xi’an), fell to the Xiongnu in 316, marking the end of Han Chinese control in the north. The Jin emperor and his successor were captured and killed, and at least a million people—including many Buddhist monks—fled south to escape slaughter.

Among those who remained in the north and survived was a woman named Zhu Jing Jian (ca. 292–361), who is recorded as the first Chinese woman to receive ordination as a novice nun. She was ordained, the records say, by an Indian teacher in Luoyang in 317. Later, she founded a convent in Chang’an.

North and South

Many people fleeing the nomadic armies in the north crossed the Yangtze River into southeastern China. A cousin of the slain Jin emperor assumed his title and established a new court in Jiankang, or modern-day Nanjing. The Jin officials who had escaped the Xiongnu joined him there. Thus began the Eastern Jin dynasty (317–420), which, though nominally a monarchy, functioned more as an oligarchy of squabbling aristocratic families.

About this time, a shift was taking place in the relationship between Buddhism and the Chinese people. At first, the religion was associated with the many merchants coming from the western regions, as well as with missionaries from India. Although some Chinese had taken an interest in Buddhism and had even joined the monastic sangha, educated and aristocratic Chinese people primarily remained Confucian.

But as the Han intelligentsia of China congregated in the south, this attitude changed. Educated people finally came into contact with Buddhist monks and scholars who were not “barbarians,” meaning they were either ethnic Han Chinese or thoroughly Sinicized. Chinese scholars learned of a rich philosophical tradition as sophisticated as their own. A “gentry Buddhism” that stressed learning, philosophy, and debate developed among the southern Han aristocrats.

The situation in the north was messier but in some ways more fertile for the dharma.

At the time Luoyang fell in 316, north China had already been fracturing into small, short-lived states. The period from 304 to 439 saw sixteen such states wink into and out of existence there.

The nomadic tribes that had conquered the north were not a genteel crew; many of their leaders maintained power through brutality and terrorism. One such leader was Shi Hu, head of the Later Zhao polity (319–351), who sometimes slaughtered the entire populations of villages he captured. He also executed officers who disagreed with him and murdered at least two of his wives. Once Shi Hu grew angry with his own heir and had him killed, along with the heir’s consorts, their twenty-six children, and over two hundred retainers.

Yet even amid this chaotic violence, Buddhism was embraced in the north. A missionary named Fotudeng (232–348) came from Kucha, a small central Asian kingdom, and managed to impress the terrible Shi Hu and other northern warlords. He did this, ancient sources say, through magic tricks, such as conjuring a lotus from a bowl of clear water. Fotudeng also had a reputation as a seer, and he became Shi Hu’s personal oracle and spiritual adviser.

Improbably, Shi Hu, who could be “charitably described as a psychopath,” 1 became a patron of Buddhism. It was said he built nine hundred monasteries and temples. And although Fotudeng comes across in history books as an opportunistic hustler, many of his disciples are remembered as outstanding scholars and practitioners who held their teacher in high regard.

There may have been more to Fotudeng than magic tricks. One can imagine him playing a dangerous game of doing whatever he had to do to placate the monstrous Shi Hu and allow Buddhism to flourish. In time Fotudeng’s many disciples traveled and taught throughout north China and possibly as far south as Guangzhou, where we’ve left Bodhidharma by the dock.

The Translators

The spread of Buddhism into China was aided by improved translations of Buddhist sacred texts. Among the many translators who brought the dharma to China, two stand out.

Dharmaraksha (ca. 230–307) was the son of a Kushan merchant living in Dunhuang. He received a Chinese education and was also prolific in Indian and central Asian languages. A sixth-century catalog of Chinese Buddhist texts attributed 154 translations to him, including the Pancavimsatisahasrika Prajnaparamita Sutra (better known in English as the Perfection of Wisdom in Twenty-Five Thousand Lines) and the Lotus Sutra.

But Dharmaraksha didn’t just passively sit in a temple translating texts. He traveled west to Gandhara to collect sacred texts not yet available in China. He also traveled to other cities in north China, spreading knowledge of these scriptures as he went.

And then there was Kumarajiva (344–413), the most renowned of all the early translators. Like Fotudeng, Kumarajiva was from Kucha in central Asia. In his youth he studied with the Sarvastivadins in Kashmir, but he later converted to Mahayana. His reputation as a scholar of the dharma grew.

And then his life got interesting. In 379 Fu Jian (337–85), leader of the Former Qin dynasty of north China (351–94), heard of the great scholar Kumarajiva and desired to bring him to his court. Fu Jian ordered his general, Lu Guang, to take a delegation to Kucha and escort the scholar to his capital at Chang’an.

But Lu Guang rebelled. He did go to Kucha, but instead of returning to Chang’an, he set himself up as a warlord and made Kumarajiva his hostage. The scholar remained a captive for seventeen years. In the meantime, Fu Jian died and the Former Qin dynasty crumbled.

Kumarajiva was not forgotten, however. He was rescued in 401 after Yao Xing (366–416) of the Later Qin (384–417) ordered his armies to defeat Lu Guang and bring Kumarajiva to Chang’an.

It’s said that during his time in captivity Kumarajiva occupied himself by learning Chinese, so he was well prepared for the next phase of his career. Beginning in 402, he spent the remaining eleven years of his life translating many of the great Mahayana texts. These included the Vimalakirti Sutra and classics of the Madhyamaka/perfection of wisdom literature, such as the Ashta, the Diamond Sutra, Nagarjuna’s Fundamental Verses on the Middle Way , and a commentary on the prajnaparamita sutras attributed to Nagarjuna. Through his translations and through his many students, correspondents, and collaborators (which included several disciples of Fotudeng), he was able to raise understanding of Madhyamaka far above what it had been before in China—a necessary precursor to the appearance of an indigenous Mahayana school such as Zen.

The quality of Kumarajiva’s work remains relevant to this day. Many of the original texts are lost, and scholars still rely on Kumarajiva’s translations. A substantial portion of Mahayana sutras that have been published in English were translated from Kumarajiva.

The Scholars

I wrote earlier that many elements of doctrine and practice associated with Zen arrived in China before Bodhidharma. Two scholars in particular are worth noting for their impact on Zen.

Sengzhao (378–413) was a student and collaborator of Kumarajiva who is remembered for his influential analysis of Madhyamaka, which he made using idioms from Confucianism and Daoism. In spite of his mastery of words, Sengzhao maintained a distrust of them. “The sphere of Truth is beyond the noise of verbal teaching,” he wrote. “How then can it be made the subject of discussion? Still I cannot remain silent.” 2

The paradox of expressing the ineffable is one of Zen’s (and philosophical Daoism’s) persistent themes. I am reminded of the words of the ninth-century master Dongshan Liangjie: “Just to portray it in literary form is to stain it with defilement.” 3 Yet words can be useful, and sometimes something needs to be said.

Heinrich Dumoulin writes that the relationship of Sengzhao to Zen “is seen in his orientation toward the immediate and experiential perception of absolute truth.” 4 The prominent Buddhologist Bernard Faure notes that in the early records Sengzhao is something of a double of Bodhidharma but is also sometimes described as a rival of Bodhidharma. 5

Zhu Daosheng (355–434), who also was a student of Kumarajiva, promoted the idea that enlightenment could be realized in a single, immediate experience of insight. This “sudden enlightenment” is possible because buddha-nature permeates all beings; thus, enlightenment is already present. This bit of doctrine would become critical to the formation of Zen. At least one ancient Chinese scholar nominated Zhu Daosheng as the true First Patriarch of Zen.

The Daoist Connection?

While we’re talking about translations and scholarship, it’s worth noting that many Western histories of Chinese Buddhism explain that early translators borrowed from the vocabulary of Daoism to render a number of essential Sanskrit words into Chinese. This led, they say, to a comingling of Daoism and Buddhism during the period when Buddhism was introduced to China, and it was this comingling that created Zen.

In the twentieth century, Western Zen aficionados such as Alan Watts promoted the notion that Zen was at least as much Daoist as Buddhist, if not more so. Today the Zen-Is-Daoism theory pervades many Western views of both Daoism and Zen. But more recently, some knowledgeable people have concluded that the influence of Daoism upon Zen has been exaggerated and that the similarities are more about style than substance. 6 I believe this view is the more accurate one.

Yes, early Chinese Buddhism, and not just Zen, borrowed vocabulary from Daoism and also Confucianism to translate Sanskrit words. Dharma became dao , for example. But that doesn’t mean that what the Buddhists meant by dao was identical to the Daoist understanding of dao. Further, the historical record does not show us a simple, linear influence of Daoism that uniquely influenced Zen and not other schools of Chinese Mahayana as well.

China already had a deep and sophisticated tradition of philosophical inquiry and scholarship when Buddhism arrived, and the new religion was absorbed into that. It’s true that some of the Chinese scholars who first studied Buddhism had a background in Daoism, but all of them had a background in Confucianism, which functioned as a pervasive civic, philosophical, and religious worldview. Further, the Chinese did not assume that truth had to reside in only one religion or school of thought, and they were brilliant at syncretization. This is not to say China in the first millennium was a religious melting pot; the three traditions often engaged in heated rivalries and robust name-calling. Even so, the three major religious/philosophical traditions of China—Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism—influenced each other on many levels, and this influence can be found in schools of Buddhism other than Zen. Chinese Buddhism—by which I mean the Buddhist traditions that emerged in China and eventually spread to Korea, Japan, and beyond—is subtly distinctive from the Buddhism of Southeast Asia and Tibet for that reason.

So, although Zen and Daoism do share points of agreement, Zen is best understood within the context of Mahayana Buddhism. Although Zen in China sometimes adopted Daoist vocabulary and iconography, it’s important to be aware that the perspectives behind the words and images differed from Daoist ones. I believe making too much of the Daoist-Zen connection gets in the way of understanding Zen, and no doubt it gets in the way of understanding Daoism as well.

Buddhism in Fifth-Century China

By the fifth century, nuns, monks, and Buddhist temples were common sights in China. By then they had converted the shoulder-baring saffron robes of India into something more modest and Chinese—a warmer, sleeved robe around which was wrapped the traditional rectangular samghati, with its rice-field pattern. 7

This century saw several significant milestones in Chinese Buddhist history. Here are just a few:

In 402, the monk Huiyuan (334–416) established the White Lotus Society on Mount Lushan in modern-day Jiangxi Province, south of the Yangtze River. This White Lotus Society (there were several in Chinese history) is considered the forerunner of Pure Land Buddhism, which is the dominant form of Buddhism in East Asia to this day.

We’re going to be running into Pure Land a lot throughout this book, so it needs to be defined. Very simply, the many Pure Land sects consider enlightenment to be a birthright of all beings, but it is terribly difficult to realize that birthright amid the cacophony of life. Faith in the transcendent buddha Amitabha, “infinite light,” enables one to enter a pure land where dharma teachings are abundant and every condition is conducive to realization. This pure land is often understood as a physical place, but it also is understood as a state of mind to be cultivated through practice. However, reaching the pure land is not enlightenment itself, and even while there, one may miss the opportunity to achieve enlightenment and instead fall back into suffering. The most common practice of Pure Land Buddhism is chanting the name of Amitabha. Because it doesn’t require long hours of silent meditation and other monastic practices, Pure Land developed a strong following among laypeople. Huiyuan also engaged in a famous correspondence with the translator Kumarajiva in north China, which tells us that the political divisions of the time were not an unsurmountable barrier to the dharma.

In 434, nuns from Sri Lanka traveled to China to offer full ordination to their Chinese sisters. This is significant because the Vinaya states that full ordination can be given to women only in the presence of other fully ordained nuns as well as monks, thus supposedly ensuring an ordination lineage that goes back to the first nun, Mahapajapati, who was ordained by the Buddha. With no fully ordained nuns in China, women such as Zhu Jing Jian received novice ordination only. The Chinese nuns’ lineage established in 434 survives today in China, Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan, and Korea.

The establishment of the Chinese bhikshuni sangha —the order of nuns—was a significant development in Chinese culture that is often overlooked. It gave women the option to live a life other than that of a wife or servant. For some, it opened a door to a life of scholarship that before had been for men only. Many nuns came to be widely known for their mastery of Chinese classics as well as of Buddhist scriptures.

One other note: Over the centuries the nuns’ order in Sri Lanka died out. It was revived in 1996, when nuns from Korea traveled to Sri Lanka to attend the ordinations of their Sri Lankan sisters, thus returning the women’s ordination lineage from East Asia to its original home in South Asia.

Back to the fifth century: Gunabhadra (394–469), a scholar of central India, arrived in China about the year 435. He resided and worked in southern China, in Jiankang and then Jingzhou, farther west. He translated fifty-two scriptures—including the Lankavatara Sutra, which is associated with Yogacara—into Chinese. The Lankavatara went on to develop a devoted following in China and would play a role in early Zen history.

In 439, a political milestone was reached in north China. For several decades the Northern Wei dynasty (386–535) had been expanding its territory, conquering one smaller state after another. The last of these surrendered in 439, and north China was unified.

In 477, the emperor Xiaowen (467–99) of the Northern Wei commissioned the building of a Buddhist temple/monastery on a tree-covered mountain called Shaoshi, in modern-day Henan Province. Shaoshi is a central peak of Mount Song, considered sacred by Daoists. The temple was named Shaolin.

And we have left Bodhidharma in Guangzhou long enough.

Bodhidharma, the First Patriarch

Although I’ve described Bodhidharma as a flesh-and-blood monk stepping off a boat into fifth-century Guangzhou, the truth is we don’t know with absolute certainty that he was a real person. Even assuming he did exist, most of what we think we know about him comes from accounts written to establish Bodhidharma’s importance to Buddhism, not to document biographical facts. The early records must be taken with a huge grain of salt. And we must also entertain the possibility that there was more than one foreign monk in China going by the name Bodhidharma. “Awakening to the dharma”—it’s not a terribly original name.

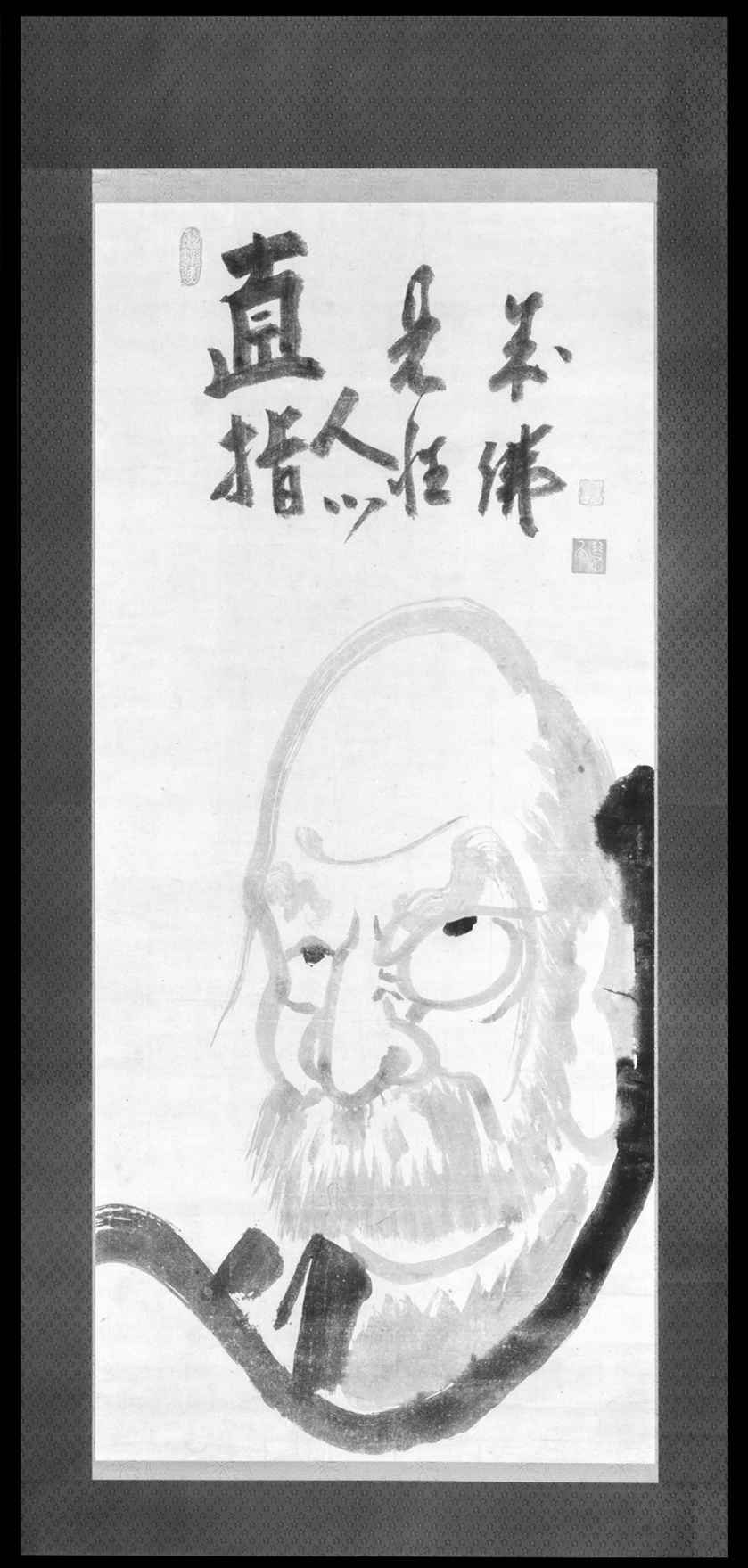

Figure 3. An eighteenth-century hanging scroll portrait of Daruma (Bodhidharma) by Hakuin Ekaku.

Image: 44 1/2 x 19 3/4 in. (113.03 x 50.17 cm.); Mount: 77 3/4 x 25 in. (197.49 x 63.5 cm.) Courtesy of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Gift of Murray Smith. (M.91.220) Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA.

The oldest known mention of Bodhidharma is in a mid-sixth-century record, the Luoyang qielanji (The monasteries of Luoyang), completed in 547 by Yang Xuanzhi. The text mentions in passing that the monk Bodhidharma came to Luoyang to heap praise upon the Yongning Temple, which was built in 516. This Bodhidharma was described as being a man from “Po-ssu in the western regions” (possibly Persia) who claimed to be 150 years old.

On the other hand, among the Dunhuang scrolls was one by Tanlin (506–74), thought to be a disciple of Bodhidharma’s successor Huike. Tanlin wrote that Bodhidharma was from southern India and the third son of a king. This was part of the preface to a work attributed to Bodhidharma, Two Entrances and Four Practices. While the preface is obvious hagiography, I believe this is the only description of Bodhidharma that was written by someone who might possibly have met Bodhidharma, or at least might possibly have known his disciple Huike. However, like everything else about Bodhidharma’s biography, factuality should not be assumed.

The Dunhuang scroll mentioned at the beginning of this chapter was by the scholar Daoxuan (d. 667). Daoxuan tells us that after Bodhidharma was snubbed by the gentry Buddhists in the South, he traveled to the Northern Wei capital. At that time the capital would have been Pingcheng, or modern-day Datong. Or, after the year 493, the capital would have been Luoyang.

To compound the uncertainty, later accounts say that Bodhidharma arrived in China sometime after 500 and was received by the emperor Wu (464–549) of the Liang dynasty (502–87), whose capital was Jiankang, south of the Yangtze River. The emperor Wu is remembered as a devout Buddhist who built many temples and monasteries.

This famous exchange between the emperor and Bodhidharma is described in the Biyan lu, or Blue Cliff Record :

Emperor Wu of Liang asked the great master Bodhidharma,

“What is the highest meaning of the holy truths?”

Bodhidharma said, “Empty, without holiness.”

The Emperor said, “Who is facing me?”

Bodhidharma replied, “I don’t know.” 8

This is a dialogue every student of Zen hears. But the Blue Cliff Record is a koan collection compiled in 1125, not a history book.

Leaving the emperor Wu of Liang (the later story continues), Bodhidharma floated across the Yangtze River on a reed and continued north until he found the Shaolin Temple. Upon reaching Shaolin, he chose to sit in meditation in a nearby cave for the next nine years. The legends of Bodhidharma in the cave are beyond counting. In a story my first Zen teacher liked to tell, a small boy entered the cave and threw a rock that hit Bodhidharma in the head, causing the old master to realize great enlightenment. I am grateful that incident didn’t turn into a ritual.

In another legend, a sleepy Bodhidharma tore off his eyelids to stay awake. This is why he appears to be bug-eyed in many portraits. The cast-aside eyelids grew into the first tea plants. He is said to have sat still for so long his legs withered away, which inspired the legless Daruma dolls popular in Japan. He is also said to have encountered his successor Huike in the cave, but we’ll get to that story later.

Accounts of Bodhidharma’s life after he left the cave also are contradictory. He lingered somewhere long enough to teach for a while, but that somewhere may have been Luoyang, not Shaolin. Tanlin mentions only two disciples, Huike and Daoyu. Accounts written later add two more: a monk named Daofu and a nun, Zongzhi. Regarding Zongzhi, later sources identify her as a daughter of the emperor Wu of Liang. I’ve not been able to corroborate that. It is also possible that Zongzhi was an invention based on the memory of Yuan Ji, an enlightened nun who makes appearances in Dunhuang scrolls.

In later Zen literature Bodhidharma often is referred to as a “blue-eyed” or “red-bearded” barbarian. This description arose among people who never saw the living Bodhidharma, and it probably shouldn’t be taken literally—a good rule of thumb when dealing with any Zen literature, actually. The description may suggest Bodhidharma came to China on the Silk Road from the West, and not from India. Or it might just be some sort of Tang dynasty joke.

If you are wondering: Although the Shaolin Temple is famously associated with kung fu, there’s no indication in the early Zen records that Bodhidharma had anything to do with martial arts. He appears to have been a very peripheral figure while living at Shaolin, quietly teaching his two, or four, students when he wasn’t meditating in a cave.

But what did Bodhidharma teach?

Two Entrances and Four Practices

Four sermons attributed to Bodhidharma survive to the present day. Of those, the brief Two Entrances and Four Practices, prefaced by Tanlin in the sixth century and discovered at Dunhuang, has the strongest claim to being a genuine work of Bodhidharma’s. The authorship of the others is disputed, in part because they don’t appear to be old enough to have been composed by Bodhidharma.

But even though the text is old enough, the scholar John McRae points out that Two Entrances reads as if it were composed in Chinese by a native speaker, which Bodhidharma was not. 9 Perhaps, we might speculate, this is Bodhidharma’s teaching as expressed by Huike.

Whoever wrote it, it’s the oldest text associated exclusively with the Zen school. So let’s take a look at it.

The sermon begins by saying there are two ways to enter the path. In Chinese, these two ways are liru and xingru. Of these, the word liru is the most problematic; there seems to be no precise English counterpart. Some translators render it as “principle,” while others translate it as “reason.” But “reason” makes little sense in context. One source explains that liru signifies “an intuitive insight into the Dharma and a recognition of the fact that each and every person was innately endowed with the capacity for enlightenment.” 10 I think “principle” is a bit closer than “reason.”

The entrance by principle is to be awakened by teaching, the text continues. But “awakened by teaching” doesn’t refer simply to learning doctrines. This awakening requires a profound faith that the true nature of all beings, ordinary and enlightened, is the same. This true nature is, for most people, obscured by the delusional impressions of our senses and perceptions. Discard the false and take refuge in the true. Be still; engage in wall contemplation so that distinctions between self and other, ordinary person and enlightened being, fall away. Not being swayed by written teachings, abiding peacefully in deep accord with principle without discrimination—this is called “entrance by principle.”

The important points being made here are that the fundamental principle, or true nature—tathagatagarbha, or buddha-nature, discussed in chapter 1—is already present even though we may not see it. We practice meditation with eyes open, facing a wall—something Zen students still do—and delusions fall away. This is accomplished without relying on written scripture. If you are a Zen student, these themes will be very familiar.

Entrance by xingru, or practice, leads us to the four practices. Very briefly: The first practice is accepting whatever befalls us without complaining about injustice. The second is adapting to conditions and accepting that we are ruled by conditions, not by ourselves. The third is to practice non-craving. The fourth is practicing the dharma.

This part of the text probably doesn’t sound all that appealing to the casual reader. Without going into a long-winded sermon…ultimately, these practices are about realizing the illusory nature of the self and being liberated from self-clinging. One may indeed be a victim of injustice, for example, but if we dwell on that injustice, we are clinging to a self. The four practices point to something that Zen students sometimes overlook, which is that Zen is more than meditation and koans. It’s how one engages with everything in life, moment to moment, fortunate and unfortunate.

I like what the Zen teacher James Ford said about Bodhidharma’s practices:

Here we’re invited to surrender to the realities of the flux of events, and out of that to learn the dance of relationships, to see into the reality that we are, all of us, boundless, our essence is no essence at all, just openness, and from there to realize our lives just as they are, when not clung to, are the Dharma, the dharmakaya, the great open itself. No difference. 11

I would like to add that there’s nothing at all wrong with taking steps to improve a situation; Zen practice is more a matter of not identifying with or attaching to the situation, improved or not.

Of practicing the dharma, the text says, the dharma is the principle of essential purity.

According to this principle, all characteristics are nonsubstantial and there is no defilement and no attachment, no [distinction between] “this” and “that.” The [Vimalakirti] Sutra says: “There are no sentient beings in this Dharma, because it transcends the defilements of ‘sentient being.’ There are no selves in this Dharma, because it transcends the defilements of ‘self.’ ” 12

If you are a Zen student or a student of Mahayana Buddhism, that ought to sound familiar. If you aren’t and if you are completely baffled by this, you might review the discussion of Madhyamaka philosophy in chapter 1. But I advise against intellectual analysis. Where Zen literature is concerned, little good comes from that.

There are several translations of Two Entrances and Four Practices easily found on the web. Again, this brief sermon is the only text that historians say could be the work of Bodhidharma. This well-known definition of Zen attributed to him appeared centuries later:

A special transmission outside the scriptures;

No dependence upon words and letters;

Direct pointing to the human mind;

Seeing into one’s nature and attaining Buddhahood.

The scant records of the time and location of Bodhidharma’s death also contradict each other. Some legends say Bodhidharma returned to India before his death, and others claim various places in China to be where he died. Daoxuan wrote that Bodhidharma died on the Luo River, which has led to speculation among historians that the First Patriarch was killed in a mass execution that took place on the Luo River in 528.

However he departed, Bodhidharma dropped out of our story before the fall of the Northern Wei dynasty in 534. An old stupa that still stands near Luoyang is said to mark Bodhidharma’s grave.

For what it’s worth, I think there really was a meditation master named Bodhidharma who taught in the Northern Wei kingdom in the early sixth century. It appears he attracted little notice while he was alive. But he was the teacher of Huike, who (as we shall see) made a bigger splash. And as Zen took shape as a distinctive school, the previously overlooked life of Bodhidharma became the stuff of legend.

Dazu Huike, the Second Patriarch

In the traditional story, Dazu Huike (487–593) went to Shaolin and found the great master Bodhidharma meditating in his cave. But Bodhidharma refused to acknowledge Huike. Huike stood in a heavy snowfall outside the cave and waited through the night for Bodhidharma to so much as say a word. The snow piled up to Huike’s waist, and tears froze on his cheeks.

Finally, in desperation, Huike cut off his arm and gave it to Bodhidharma, crying, “My mind has no peace! Please, master, put my mind at rest!”

“Bring me your mind, and I will put it at rest for you,” Bodhidharma said.

Huike reflected on this and finally said, “I have searched for my mind, but I cannot find it.”

“There,” Bodhidharma said. “I have put your mind at rest.”

That’s the story told in the Wumenguan, or Gateless Barrier, a classic koan collection compiled by Master Wumen Huikai in the early thirteenth century. There are other variations of this story in other records and collections, but they all involve Huike waiting in the snow and then cutting off his arm to get Bodhidharma’s attention.

That’s as much as most Western Zen students ever hear about Huike. And that’s a shame, because there’s much more to his story.

One of the oldest records of early Zen is Daoxuan’s Xu gaoseng zhuan, or Further Biographies of Eminent Monks, which was completed about 645–50. Daoxuan, you might recall, was the fellow who told us Bodhidharma landed in Guangzhou in 475. Daoxuan left us a much more extensive biography of Huike than we have of Bodhidharma. Indeed, the extensiveness of Huike’s biography, written about fifty years after his death, tells us that he was still held in high regard as a significant teacher. We don’t know how much, if any, of it is factual, and it leaves us with some huge questions that probably will never be answered. But it’s something.

The manuscript of the Daoxuan’s Further Biographies was revised in the 660s or so, but historians disagree whether it was revised by Daoxuan or somebody else. Whoever revised it, there are significant differences between the two editions that are worth noting. 13 First, we’ll look at the original manuscript.

According to Daoxuan, Huike was born in about 487 in what is now Henan Province, China, about sixty miles east of Luoyang. His was a family of Daoist scholars, and as a young man Huike studied Confucianism along with Daoism.

The scholar turned to Buddhism after the deaths of his parents. In 519, when he was thirty-two years old, he was ordained a Buddhist monk in a temple near Luoyang. About eight years later, he left in search of Bodhidharma, and he found the old monk in his cave near Shaolin Temple. At the time of this meeting, Huike was about forty years old. Huike studied with Bodhidharma for six years and became Bodhidharma’s chief dharma heir and successor.

The Fall of Northern Wei

If Daoxuan’s dates are correct, Huike would have become Bodhidharma’s successor by the year 533. In 534, Daoxuan says, Huike was teaching in Luoyang. And here we must place Daoxuan’s biography of Huike into a larger historical context.

Several years earlier a rebellion had begun among the Xianbei people living on the northern frontier. The rebellion spread. In 534, the capital Luoyang fell to the rebels, and the last emperor of Northern Wei was deposed. The rebel general who captured Luoyang marched the entire population of the city to Ye, also called Yedu, about two hundred miles northeast. The general then named himself the first emperor of Eastern Wei.

Daoxuan simply tells us Huike went to Ye in 534; we can only assume the forced march had something to do with his relocation.

Although the rebels who brought down Northern Wei had several grievances, the major underlying grievance was that the Chinese and non-Chinese people of Northern Wei never became a unified nation. And as time went on, the rulers of Northern Wei favored the Chinese, causing resentment among the nomadic tribespeople who had conquered the region.

Several Northern Wei rulers had tried to use Buddhism to unify the people. But this may have backfired, for several reasons. The Northern Wei emperors established a bureaucracy to govern Buddhist affairs, making themselves the chief spiritual authority over all monks and nuns. At the same time, monastics were exempt from taxation and from having their labor conscripted. Furthermore, while monastics were resented for being tax cheats and idlers, the emperors had also invested a huge amount of treasure and labor into the vast, art-filled Buddhist grottoes of Yungang, near Pingcheng, and Longmen, near Luoyang. So, when Northern Wei fell and their imperial protection was lost, Buddhist clergy had reason to feel anxious about their futures.

Figure 4. Sculptures in Yungang grottoes, near Datong City, Shanxi Province, China. Most of the figures at Yungang were carved in the fifth century under the sponsorship of Northern Wei emperors. Resentment over taxes and conscripted labor needed for the Yungang project were a factor in the fall of Northern Wei.

Photo 95988379 © Anaellemeriller Dreamstime.com .

Daoxuan tells us that in Ye, Huike attracted many followers. A prominent teacher named Daoheng became angry at Huike’s teachings and jealous of his popularity, and Daoheng arranged for Huike to be persecuted. Daoheng even hired someone to assassinate Huike, but Huike converted the assassin first.

Daoheng’s antagonism to Huike has been explained by some historians as a doctrinal conflict between the teachings of the earlier Madhyamaka scholar Sengzhao and Huike’s Zen. Given the volatility of the time, however, one suspects Daoheng was mostly concerned about keeping the favor of the Eastern Wei court.

It’s also recorded that, after receiving dharma transmission from Bodhidharma, Huike left monastic life and for a time became an itinerant laborer. This seems an odd career move for a lifelong scholar approaching his fiftieth birthday, but he told people the life of a laborer was best to acquire humility and to tranquilize his mind. And, anyway, what he did with his own life was his business. This supposedly happened before he traveled to Ye, but it may have happened after. Perhaps working as a laborer was Huike’s way of keeping his head down for a time.

During the long years Huike lived and taught near Ye, the political situation in northern China remained dangerous. New dynasties seized power and soon met violent ends. In 574 another emperor Wu, in this case of the Xianbei dynasty of Northern Zhou, attempted to abolish Buddhism. Fearing for his safety, Huike fled south. He found a hiding place in the mountains of southern Anhui Province, near the Yangtze River. He lived quietly among the pines and misty peaks, yet students still sought him out. He continued to teach.

The Lankavatara Sutra

It appears Huike was a formidable teacher. But what did he teach? We have little information to go on. The one bit of writing attributed to him has been red flagged by historians as suspect. Going back to Bodhidharma’s Two Entrances , we can see an unmistakable influence of Madhyamaka, and it’s probably safe to assume that Huike taught Madhyamaka doctrines as well.

In the revised version of Daoxuan’s Further Biographies, however, we find this:

In the beginning Dhyana Master Bodhidharma took the four-roll Lankā Sūtra, handed it over to Hui-k’o [Huike], and said: “When I examine the land of China, it is clear that there is only this sutra. If you rely on it to practice, you will be able to cross over the world.” 14

The “four-roll Laṅkā Sūtra” would have been Gunabhadra’s translation into Chinese of the Lankavatara Sutra, mentioned earlier in this chapter. The revised Further Biographies goes on to say that Huike’s students taught this sutra also. It’s still widely presumed that the Lankavatara was the most essential sutra in early Zen.

However, there is reason to believe the connection between Bodhidharma/Huike and the Lankavatara Sutra is a post hoc invention. These suspicions also apply to the appearance of Bodhidharma and Huike in another record, the Léngqié shῑzῑ jì (Record of the Lankavatara Sutra masters). This record dates to the early eighth century, a time when the tradition that eventually would be called Zen was prominent enough that it needed a respectable history, even if one had to be invented.

A side note: The revised Further Biographies contains a story of Huike losing his arm to bandits. Since this text predates all known accounts of Huike slicing off his arm to get Bodhidharma’s attention, this would appear to be the more likely story of how Huike lost his arm. Of course, at least one historian argues that even this account is hagiography and that Huike was perfectly sound. 15

Huike’s Last Days

A new dynasty arose in 581 to seize power in north China, and by 589 the emperor Wen of Sui had conquered south China as well. Wen had been raised a devout Buddhist, and during his reign of the reunited China he founded nearly four thousand new temples, convents, and monasteries. The suppression of Buddhism ended.

In time, Daoxuan tells us, a very elderly Huike returned to northern China. He told his students he had to repay a karmic debt. One day in 593 a prominent priest accused Huike of heresy, and magistrates had the old man executed. He was 106 years old.

And here our story of Zen might end, because the original version of Daoxuan’s Further Biographies tells us that Huike died without naming a dharma heir. The revised text, however, named an heir—Jianzhi Sengcan.

Jianzhi Sengcan, the Third Patriarch

For centuries, Jianzhi Sengcan (529–606) was the transmission link between the Second Patriarch, Huike, and the Fourth Patriarch, Dayi Daoxin. However, Daoxuan’s Further Biographies includes a biography of Daoxin that does not connect him to Sengcan. The earliest extant text linking Sengcan and Daoxin was composed about 690 or shortly after.

By now it’s broadly believed, even within Zen, that Sengcan’s name was patched into Zen history. His name most likely was plucked from a list of scholars of the Lankavatara Sutra to strengthen the connection between Bodhidharma/Huike and that text.

The only significant detail in Sengcan’s traditional biography is that he wrote the revered Xinxin ming (Verses on the Faith Mind ), still studied by Zen students today. But the historians tell us that’s not true; the Xinxin ming probably was composed later, by somebody else, they say.

It’s not impossible that Sengcan studied with Huike, and maybe someday some documentation will be uncovered that gives us a clearer picture of this bit of history. At present, however, what evidence we have says he had no direct connection to Zen. Let us simply assume that Jianzhi Sengcan was a dedicated scholar and lovely human being and move on.

Dayi Daoxin, the Fourth Patriarch

The Sui dynasty had united China and accomplished much, including another rebuilding of the unfortunate city of Luoyang. But the Sui dynasty soon crumbled under multiple rebellions.

At one point, records say, the Sui general Wang Shichong made the mistake of occupying property belonging to the Shaolin Temple. Kung fu monks joined the rebellion and defeated the general, thereby retaining title to the temple’s property. This bit of history was commemorated in the 1982 martial arts film Shaolin Temple, starring Jet Li. The Sui dynasty ended officially in 618.

So it was that Dayi Daoxin (580–651) had the good fortune to live at the dawn of the great Tang dynasty (618–907). He especially benefited from the stability established by the emperor Taizong, who reigned from 626 to 649 and who is revered as one of China’s greatest leaders.

Taizong may or may not have been a devout Buddhist himself. But during his reign, Buddhism eclipsed Confucianism as the dominant religion/philosophy of China, a status it would maintain for two more centuries. The marriage of his daughter Princess Wencheng to King Songtsen Gampo in 641 marks another important moment of Buddhist history: the introduction of Buddhism to Tibet.

It’s said Taizong gave Daoxin the name Dayi, “Great Healer.” Records of Daoxin’s life are sketchy, but we do know that he established his temple on Shuangfeng, “twin peaks,” near modern-day Huangmei in Hubei Province. Daoxin called his temple Yuchu, “secluded residence,” and he taught there for thirty years. Yuchu is considered the first Zen monastic community, even though Zen wasn’t recognized as “Zen” yet.

Here we run into another point about which Zen tradition and historians disagree. Buddhist monasteries traditionally had depended on the alms of benefactors. But, according to Zen tradition, Daoxin and his students formed a kind of commune, and the monks grew most of their own food. Zen practice was no longer something done only in a meditation hall; gardening, cooking, administrating, cleaning, and other chores also were practice. Yuchu became a template that Zen communities have followed ever since, Zen tradition says.

Historians, however, believe that the tradition of “work practice” developed later. The historian John McRae, for instance, writes that “there is no evidence whatsoever that these monks participated in anything other than meditation and ordinary religious services.” 16

But Daoxin’s community may have established precedent in other ways. The author and translator Red Pine comments that over the next two centuries “almost every monk who was instrumental in the early development of Zen” would follow Daoxin’s example and seek out remote, high mountain basins with a generous amount of arable land as sites for monasteries. 17

Zen teachers and communities did sometimes move to urban areas. In fact, in the decades after the death of Daoxin’s heir, Hongren, Zen entered a “metropolitan” phase as teachers and students for a time converged in the imperial cities of Luoyang and Chang’an. Even so, Zen’s tendency to distance itself from population centers—and the imperial court—may have enabled it to survive in China when other Buddhist sects did not. But that’s getting ahead of our story.

What did Daoxin teach? As with most other early teachers, there is no teaching that can be attributed to him with absolute certainty.

It’s believed Daoxin valued meditation as the most essential practice. “Sit earnestly in meditation!” he is reputed to have said. “The sitting in meditation is basic to all else.” Traditional sources associate Daoxin with the Lankavatara Sutra and also with the prajnaparamita sutras, known for their deep teachings on Madhyamaka.

Daman Hongren, the Fifth Patriarch

Daman Hongren (601–74) spent his entire life around Mount Shuangfeng; he was born there, studied with Daoxin there, taught there, and died there. He broke with the tradition of striking out on his own after receiving transmission, and instead he stayed with Daoxin.

Three years after Daoxin’s death, Hongren decided to establish another monastery. The new monastery was only a half-day’s walk east from Daoxin’s place, and it came to be called Dongshan, or “East Mountain.” Daoxin’s and Hongren’s legacy of instruction would come to be called the East Mountain teachings.

What were the East Mountain teachings? John McRae writes,

Daoxin and Hongren taught meditation and nothing else. In all the material we have about them, there is no reference to their advocating or practicing sutra recitation, devotion to the Buddha Amitabha, or philosophical analysis—in contrast to the numerous references to them as meditation teachers. 18

Hongren taught monks of many schools of Buddhism. They came to him specifically to study with a meditation master and usually stayed only months and not years.

From the Dunhuang library we have a text called the Xiu xin yao lun, known in English as The Essentials of Cultivating Mind, that is said to be the sayings of Hongren compiled by his students. Here are some of them:

“When you are right in the midst of realizing the Dharma Body, who is experiencing that realization?”

“Without doing anything or performing anything, every single thing is the great, complete nirvana.”

“When you are right in the midst of doing cross-legged sitting dhyana inside the monastery, is your body also doing sitting dhyana beneath the trees in the mountains? Are all soil, wood, tiles, and stones capable of doing sitting dhyana? Are soil, wood, tiles, and stones also capable of seeing forms and hearings sounds, putting on a monk’s robe and taking up a begging bowl?” 19

Hongren taught several meditation techniques; here is his description of one of them:

Make your body and mind pure and peaceful, without any discriminative thinking at all. Sit properly with the body erect. Regulate the breath and concentrate the mind so it is not within you, not outside of you, and not in any intermediate location. Do this carefully and naturally. View your own consciousness tranquilly and attentively, so that you can see how it is always moving, like flowing water or a glittering mirage. After you have perceived this consciousness, simply continue to view it gently and naturally, without it assuming any fixed position inside or outside of yourself. Do this tranquilly and attentively, until its fluctuations dissolve into peaceful stability. This flowing consciousness will disappear like a gust of wind. When this consciousness disappears, all one’s illusions will disappear along with it, even the [extremely subtle] illusions of bodhisattvas of the tenth stage. 20

This strikes me as a good description of a mature practice of shikantaza , a Soto Zen meditation many of us do today.

Hongren and the East Mountain meditation teachings were respected throughout China. But there are perilous curves ahead in our story of Zen.

Interlude: Joining the Patriarchs

The monk Faru (638–89) studied with Hongren for sixteen years and served as his teacher’s attendant at least part of that time. He is thought to have received dharma transmission from Hongren. His chief significance to our story is that he may have been the originator of the Zen tradition of a transmission lineage that reached back to the historical Buddha. The first known expression of that tradition, albeit in a rudimentary form, was Faru’s epitaph: “The transmission [of the teachings] in India was fundamentally without words, [so that] entrance into this teaching is solely [dependent on] the transmission of the mind.” 21

Faru’s epitaph doesn’t follow precisely what came to be the orthodox transmission lineage we know today. According to the epitaph, for example, the Buddha transmitted the dharma to his cousin and attendant Ananda rather than to the disciple Mahakashyapa. Ananda received the Buddha’s teachings and transmitted them to Madhyantika, a monk remembered for taking the dharma into Kashmir. But in today’s Zen lineage charts, transmission went from Mahakashyapa to Ananda to a monk named Shanavasa, who is something of a mystery.

Faru’s epitaph continues, saying that these teachings were beyond words and not to be found in sutras. Further, the carriers of the teachings concealed their identities and hid their accomplishments. The teachings reached China through Bodhidharma, who transmitted them to Huike and then to Sengcan, Daoxin, Hongren, and Faru.

This epitaph—presumed to have been written shortly after Faru’s death in 689—is the first document we know of that links Bodhidharma, Huike, and Sengcan to Daoxin and Hongren. After the epitaph was published several other of Hongren’s heirs adopted the ancestry lineage also. Although we cannot know for certain what Faru, or his epitaph writer, was trying to accomplish, it’s probably safe to assume that the epitaph was meant to claim status and authority for Faru as well as for a school that was still struggling to be distinctive.

On the other hand, the scholar Alan Cole points out that the epitaph was engraved onto a stele at Shaolin. Cole argues that the stele was part of a campaign to maintain imperial favor of the temple. This campaign was connected also to an effort to clarify the temple’s ownership of the land once occupied by troops of the Sui general Wang Shichong and taken back by kung fu monks. Make of that what you will. 22

The scholar Bernard Faure has pointed out that, by this time, our tradition that would be Zen had adopted two contradictory origin stories: On one hand, Bodhidharma taught that the Lankavatara Sutra was the key to enlightenment. On the other hand, Bodhidharma was one of a long succession of masters transmitting a wordless teaching outside the sutras. 23 The latter origin story is the one that eventually prevailed, although the former one didn’t entirely disappear.

Stepping outside historical narrative for a moment—the essential question here is not about whether the narrative of a transmission lineage from the historical Buddha to the Chinese patriarchs is true, but what did it represent in seventh-century China? And the next questions would be, what does it represent today ? And does it still serve a purpose ? I believe these are questions that today’s Zen teachers and institutions need to address.

Likewise, if there really was no lineage connection between Bodhidharma and Daoxin, this leaves us with the question of what to do with Bodhidharma as the esteemed founder of Zen. I suspect Bodhidharma’s position as a revered Zen icon—resolutely unmoving and ceaselessly awake—will remain secure. Time will tell.

The Sixth Patriarchs

According to most early records, Yuquan Shenxiu (607–706) was Hongren’s successor as patriarch. Shenxiu was on everybody’s A list. He was a tall man with a commanding presence who came from an aristocratic family. He was universally respected: Students flocked to him. Scholars praised him. The empress Wu Zetian is said to have invited him to court and prostrated herself before him. And then she built him a new monastery. When he died, he was given a state funeral.

When we speak of the Sixth Patriarch today, however, we are talking about an entirely different guy—an illiterate peasant named Dajian Huineng (638–713). How did that happen?

According to the traditional story, Huineng was a poor boy from south China. One day while selling firewood on a street corner, he heard someone recite a couple of lines from the Diamond Sutra. Experiencing deep insight, he went north and sought out Hongren for teachings. He was accepted as a novice monk and put to work doing chores.

Sometime later, Hongren challenged his monks to compose a verse that expressed their understanding of the dharma. If any verse reflected the truth, Hongren said, the monk who composed it would receive the robe and bowl of Bodhidharma and become the Sixth Patriarch.

Shenxiu, who was Hongren’s senior disciple, wrote on a wall:

The body is the bodhi tree.

The heart-mind is like a mirror.

Moment by moment wipe and polish it,

Not allowing dust to collect.

Huineng was a mere novice monk, but he thought he could do better. Since he was illiterate, he had another monk write this verse for him on another wall:

Bodhi originally has no tree,

The mirror has no stand.

Buddha-nature is always clean and pure;

Where might dust collect?

Hongren publicly praised the first verse and said the second verse fell short, but later he met in secret with Huineng and presented the deeper teachings of the Diamond Sutra. Then Hongren gave Huineng Bodhidharma’s robe and bowl, the symbols of the patriarchy. However, Hongren said, “Many will not accept you. Powerful forces will align against you. You must leave at once and go into hiding in the South.” And so Huineng left.

Among Huineng’s pursuers was a monk named Huiming. When Huiming tried to seize the robe and bowl to return them to East Mountain, he found the robe and bowl would not move. This caused Huiming to have a change of heart, and he said, “I have come for the dharma and not the robe and bowl.” Then Huiming obediently received teachings from Huineng.

There is more to this story, but at the end of it Huineng is universally acknowledged as the Sixth Patriarch. And by now you probably will not be surprised when I tell you it’s unlikely any of this happened. For one thing, if we’re going by the earliest records, Shenxiu and Huineng were not in residence at East Mountain at the same time. This renders the poetry contest story improbable.

Within Zen today, it’s broadly understood that the (probably fictional) disagreement between Shenxiu and Huineng was about buddha-nature, or the tathagatagarbha teachings discussed in the first chapter. Huineng’s verse tells us that buddha-nature is already perfectly and completely present. Shenxiu’s verse seems to reflect the view that buddha-nature exists within us as a kind of seed or potentiality that must be nurtured or “polished” into full development.

Does the verse attributed to him reflect Shenxiu’s understanding? Shenxiu is said to have been greatly influenced by the Dasheng qixin lun, a text most commonly known in English as Awakening of Faith in the Mahayana . 24 Awakening of Faith supports the teaching that all sentient beings are inherently enlightened; however, because they also are deluded, enlightenment must be actualized through practice. This might be what is being said in the verse attributed to Shenxiu, but if so it’s expressed badly. So let us see if we can unravel what might have actually happened at this critical moment in Zen history.

In Zen legend, Huineng is among the great masters, second only to Bodhidharma himself. Heinrich Dumoulin wrote, “It is this figure of Huineng that Zen has elevated to the stature of the Zen master par excellence. His teachings stand at the source of all the widely diverse currents of Zen Buddhism…. In classical Zen literature, the dominant influence of Hui-neng is assured. The figure of the Sixth Patriarch embodies the essence of Zen.” 25

The poetry contest and nearly everything else we think we know about Huineng are from a text of controversial origin called the Platform Sutra, which will be discussed in the next chapter. The Platform Sutra has long been accepted as a contemporary record of Huineng’s life and teachings, but in fact it probably wasn’t written until about seventy years after Huineng died. If we disregard it, we know very little about Huineng. It’s recorded he was one of Hongren’s ten foremost disciples, although some historians dismiss that source as unreliable. He appears to have been a respected, if little noticed, teacher in good standing with the other teachers, including Shenxiu. It’s believed that for some time he lived and taught in Nanhua Temple, on Cao Creek (Caoxi) near a small town in modern-day Guangdong Province. We know the names of a few of his students. One of those students, Heze Shenhui (either 670–762 or 684–758), plays a critical role in our story. However, we don’t know for certain what Huineng taught.

There is so little contemporary evidence of Huineng that one historian goes so far as to claim that Huineng never existed and is only a literary invention of Shenhui. 26 This is possible, though it seems unlikely to me that anyone could have gotten away with inventing a dharma heir of such a prominent master as Hongren—especially while some of Hongren’s younger students were perhaps still alive and while Shenhui was blowing up the Zen establishment with his claims for Huineng’s patriarchy. Shenhui’s many critics would have called him out, I would think.

It’s more likely that Huineng was a man who drew little attention. After he left East Mountain, Huineng spent the rest of his life far away in the southern provinces; monks who wanted to be big shots in those days stayed closer to the imperial cities. How much the living Huineng resembled the Zen master par excellence presented in the Platform Sutra is not something we can know.

Since the Platform Sutra is a product of the postpatriarch period of Zen, we’ll look at it in the next chapter. For now, we will focus on how the time of the Six Patriarchs came to a messy end.

Shenhui Rocks the Lineage Boat

The central figure in this part of our story is neither Shenxiu nor Huineng but Huineng’s student Heze Shenhui.

It’s believed Shenhui began his studies with Huineng at the age of fourteen. After a few years he went north to study with other masters, including Shenxiu, but eventually he returned south and stayed with Huineng until the older teacher’s death in 713. In 720, Shenhui went north again and began to teach near Luoyang.

In 732, Shenhui became notorious when he publicly criticized Shenxiu’s heirs at a “great assembly” at Huatai, northeast of Luoyang. Over the next few years Shenhui’s criticisms became more aggressive. Shenhui’s “Northern school” had strayed from correct teachings, Shenhui said, a claim we will explore a bit later. It must be noted that Shenhui was the first person to have called out the Zen establishment as a “Northern school” or claimed the existence of a separate “Southern school.”

Further, Shenhui insisted that his teacher Huineng was the true Sixth Patriarch. To fortify this claim, he said that Huineng had received Bodhidharma’s robe and bowl from Hongren. Note that this is the oldest known mention of the robe and bowl, which suggests this feature of the Six Patriarchs legend may have been Shenhui’s invention.

At this time Shenxiu’s lineage was led by his heir Puji, by all accounts a strong and charismatic teacher. As long as Puji was alive, Shenhui’s claims gained little traction. After Puji died in 739, however, Shenhui drew bigger crowds and more notoriety. To the alarm of the Luoyang Buddhist establishment, a number of monks abandoned the Northern School teachers and began to follow Shenhui.

In 753 an official had Shenhui taken into custody and presented to the emperor Xuanzong, who interviewed Shenhui in his bathhouse. The emperor then issued an edict that sent Shenhui into exile in the provinces. As historians have pointed out, this was a cushy sort of exile that closely resembled a lecture tour. The emperor probably did not want to punish Shenhui but to just keep him away from Luoyang, for the sake of keeping the peace.

One of Bodhidharma’s four practices is accepting that we are ruled by conditions and not by ourselves. This applies to everyone, including Zen teachers and emperors. And like all phenomena—a thing of many component parts with no self-essence—Zen is shaped by the culture and conditions in which it functions, as we’re about to see when a shift in China’s political landscape ended Shenhui’s exile and had a huge impact on our story.

The An Lushan Rebellion

The story of the An Lushan rebellion is genuinely epic. Here is a brief synopsis:

The emperor Xuanzong became hopelessly besotted with the courtesan Yang Guifei. This led to wonderfully convoluted intrigues involving the Yang family, who came to dominate the court.

For reasons lost to history, Yang Guifei adopted the popular general An Lushan as her son, and she and the emperor showered him with wealth and honors. But a rivalry grew between the general and the extended Yang family, which in 755 led to war between troops loyal to An Lushan and those loyal to the emperor.

In 756 the emperor and his beloved courtesan fled to Sichuan, where he abdicated his title in favor of his designated heir. But the troops with Xuanzong demanded the execution of Yang Guifei to eliminate the influence of the Yang family, whom they blamed for all the upheaval. At her request, Yang Guifei was strangled by a piece of silk to preserve her beauty in the afterlife. The brokenhearted Xuanzong spent the rest of his life exiled in Chengdu.

This bit of history has been made into two feature films, one by the Japanese director Kenji Mizoguchi (Yokihi Yôkihi, 1955) and the other by the Chinese director Li Han Hsiang (Yang Kwei Fei [The Magnificent Concubine ], 1962). One wonders what Shakespeare or Verdi might have done with this story. But only a small part of the An Lushan rebellion concerns us, so we must move on.

The new emperor Suzong recaptured Luoyang and Chang’an in 757. Over the next few years the Tang dynasty fought many battles and eventually reasserted its rule of China. The rebellion ended officially in 763, when Suzong was presented with the last rebel general’s head.

Putting down rebellions is expensive. Suzong needed capital, and his government began to sell ordination certificates to raise it. The heirs of Shenxiu and Puji disapproved of giving Buddhist ordinations for political purposes. But Shenhui, recalled to Luoyang, proved to be a champion certificate salesman.

Shenhui was rewarded for his service with a prestigious job in the imperial chapel. Although he did not live long after this appointment, it appears Shenhui’s influence in the Tang court survived him. Shenhui was given many posthumous honors, and Suzong’s successor, the emperor Daizong, is believed to have officially recognized Shenhui as the Seventh Patriarch. For its part, Zen stopped counting patriarchs after six.

The rivalry between northern and southern factions of Hongren’s heirs continued for a time. But neither Shenxiu’s nor Shenhui’s lineages survived in China beyond the Tang dynasty. Today’s Zen teachers all claim Huineng as a dharma ancestor through two of Huineng’s other heirs.

What Was the Fuss About?

We can’t rule out the possibility that much of the controversy at the end of the Six Patriarchs period stemmed from some personal grievance harbored by Shenhui. Since we can’t reconstitute Shenhui and send him off for psychoanalysis, however, let’s assume there were genuine issues that split Hongren’s heirs. What might those have been?

First, who was the true Sixth Patriarch? The unvarnished truth is that Shenhui’s arguments in favor of Huineng don’t hold water. Shenhui may have sincerely believed Huineng deserved the title, but there’s no indication Huineng ever claimed it for himself.

According to most scholars of Zen history, Shenhui claimed that Shenxiu’s heirs were teaching a doctrine of “gradual” enlightenment, while Shenhui argued for “sudden” enlightenment. This is usually interpreted to mean that Shenhui believed true enlightenment is realized all at once and is not developed incrementally over a period of time. Today’s Zen teachers will tell you this is not an issue; gradual cultivation and sudden realization are both part of Zen.

Red Pine points out in his commentary to the Platform Sutra that while the words tun and chien can be translated as “sudden” and “gradual,” he prefers “direct” and “indirect.” “They are used by Hui-neng as synonyms for ‘straightforward’ and ‘deceitful,’ ‘pure’ and ‘impure,’ ” he writes. “Hence, time is not the issue, but attitude is.” 27

Another explanation is that Shenhui claimed the Northern school taught followers to “transcend” thoughts by gradually wiping away afflictions (greed, anger, and so on) and conceptual thinking. Shenhui argued for the development of insight to see one’s true nature, which causes the afflictions and attachment to thoughts to fall away. Shenhui may have called this “sudden” enlightenment, but for many of us this process unfolds over a period of time also.

Another way that “gradual” and “sudden” might be interpreted is that the “sudden” approach is to engage in practices—primarily meditation, the direct contemplation of mind—to clarify insight. A “gradualist” approach uses more indirect or mediated means, such as sutra study or invoking transcendent buddhas and bodhisattvas for help. In this sense, Zen really is all about being “direct.”

The least useful way to interpret “gradual” and “sudden” is to assume the words refer to how quickly one goes from delusion to awakening, although many seem to interpret it that way. And maybe Shenhui did also. In short, this is an area of Zen history that calls for a more thorough review by Zen teachers.

Let us also reflect on the injustice done to Yuquan Shenxiu, who for centuries has been portrayed only as the foil, if not the villain, in the story of Huineng. Just as Huike deserves to be better remembered than as The Guy Who Cut Off His Arm, I suspect Shenxiu deserves to be better remembered than as The Guy Who Wrote the Lame Poem.

I was struck by something written by John McRae: “Based on the most comprehensive reading of the texts pertaining to Shenxiu, it is apparent that his basic message was that of the constant and perfect teaching, the endless personal manifestation of the bodhisattva ideal.” 28 The great masters of the Zen tradition ever after have taught this also.

Shitou Xiqian was a dharma grandson of Huineng who wrote a poem called the Cantongqi, or “Identity of Relative and Absolute.” This is part of the daily liturgy in many Zen temples today, and with it, I will allow Shitou Xiqian to have the last word on the great controversy of the early Zen patriarchs.

The mind of the great sage of India

Was intimately conveyed West to East;

Among human beings are wise ones and fools,

But in the Way there is no northern or southern Patriarch.