CLASSIC ZEN IN THE SONG DYNASTY

SOMETIME during the brief Later Liang dynasty (907–23), stories began to spread in China about a Zen monk from Fenghua, in today’s Zhejiang Province, named Qieci. Qieci was an eccentric but endearing character who lived on Mount Siming and who often strolled through local marketplaces, carrying a cloth sack. Qieci’s biography is included in the Song gaoseng zhuan (Song biographies of eminent monks), compiled in 988.

In early stories the sack was said to be empty. As the legend developed, the sack was said to be full of sweets for hungry children, who followed him. The stories evolved; Qieci was said to work small miracles, such as predicting the weather or staying dry in the rain. Over time, Qieci became Budai (“cloth sack”), the laughing buddha and emanation of Maitreya, the buddha of the future. His fat and cheerful form is found throughout East Asia (and in many Chinese restaurants in the West) to this day, expressing a hope for peace, abundance, and happy, healthy children untouched by fear, hunger, and grief.

The period from the fall of the Tang dynasty in 907 to the beginning of the Song dynasty in 960 is referred to as the time of Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms. The Later Liang dynasty was the first of five brief regimes that controlled much of what is now northeast China. An eleventh-century scholar named Ouyang Xiu wrote what would become the standard history of the Five Dynasties, and he painted a bleak picture. “It would be wrong to assume a total absence of loyal men in the Five Dynasties,” he wrote. “I have found three.” 1

The Ten Kingdoms, which ruled in south China, provided more stable, albeit fragmented, governance. Some of these kingdoms became havens for Buddhists fleeing the chaos and oppression of the brittle dynasties of the North. The flood of refugees probably became particularly robust when the emperor of the last of the Five Dynasties, the Later Zhou (951–60), ordered the confiscation of all Buddhist bronze statuary to be recast as coins. It was said that 3,336 monasteries were destroyed along with the statues.

As a result, Zen monastics from across China gathered in the South and, no doubt, debated the future of their tradition. It was during this period that a collective identity called Chan, including all factions and lineages, began to take form.

One product of this transitional period was the Patriarch’s Hall Anthology, thought to have been first published in south China in 952. The Patriarch’s Hall Anthology gives us a picture of the consensual identity forming at the time. It is also widely acknowledged as the oldest extant text containing genuine “encounter dialogues,” or gongans, the anecdotal bits of dialogue that would become the primary focus of koans.

Among other things, the Patriarch’s Hall Anthology attempts an inventory of all lineages of Chan history, including lineages from Daoxin and Hongren, as well as Huineng. This had not been done before; previous records had only compiled the lineage of this or that teacher. Because there was a lingering notion that only one teacher per generation received the true dharma, there was much factional squabbling over which teacher could claim to be the “real” heir of the patriarchs.

The Patriarch’s Hall Anthology organized Zen as a distinctive tradition based on a new perspective of lineage. The lineage went from the buddhas before Buddha through the Six Patriarchs and, from there, as if from a mighty tree trunk, fanned out into many branches. Note that the lineage charts were still in, shall we say, a state of flux, as places were made for significant teachers who might otherwise have fallen off them.

We might grumble, as one historian did, that this tree-and-branches motif “is actually a façade imposed upon an entangled and by no means uniform snarl of vines.” 2 Even so, it created the container by which a unique tradition would be passed to future generations.

The Song Dynasty Begins

In 960 the emperor Taizu of Song (927–76) gained control of northern China. Taizu is remembered as a wise administrator as well as a devout Confucian. Over the next thirty years the southern kingdoms also came under Song rule with remarkably little violence.

The Song dynasty would be remembered as an age of technological, engineering, architectural, economic, and agricultural innovation. The Song Chinese invented movable type, gunpowder, the compass, and restaurants, among other achievements. Song porcelains became the first commercialized industry. Subsistence farming gave way to large-scale commercial farming.

The early Song court adopted ambivalent policies toward Buddhism. On the one hand, Buddhism was seen as a suspicious foreign element to be limited and controlled. On the other, the early Song emperors viewed Buddhism as a source of spiritual benefits. For example, clergy could be called upon to offer prayers for the prosperity of the state and the long life of the emperor. Temples that could be counted on to support the emperor and contribute to domestic tranquility were supported by the court with money, goods, and land. Especially favored temples would be honored with an imperial plaque. But it was not a trusting relationship—the government attempted to control all aspects of Buddhism, including teaching, rituals, and the appointments of abbots. Even so, Zen flourished during the early Song dynasty.

For his part, the emperor Taizu is credited for saving the only surviving full-ordination lineage of Buddhist nuns. As noted earlier, under the rules of the Vinaya, the presence of fully ordained monks as well as nuns was required for complete ordination and other empowerments for women. The Confucian Taizu, however, disapproved of men and women associating outside the home, so he changed the rules so that only nuns would ordain nuns. Monks need not be involved.

The Chinese nuns’ lineage is alive and thriving today. All others, dependent on the cooperation of monks, died out centuries ago. 3

It has to be said, though, that the status of women—and thereby the status of Buddhist nuns—appears to have deteriorated during the Song. The previously rare practice of foot binding became widespread in that era. The poet Lu You wrote of the prevalence of infanticide, which was mostly of newborn girls. Daughters who survived infancy often were sold as toddlers.

Nevertheless, the few records we have of Song dynasty nuns tell us that they could be fearless. For example, the nun Miaozong (1095–1170) was a student of Dahui Zonggao, whom we will meet later in this chapter. The senior monk of the same temple, Wanan, objected strongly to the presence of a woman. Dahui insisted that Wanan interview Miaozong. When Wanan entered the interview room, Miaozong already was there—in the nude.

Wanan pointed to Miaozong’s genitals. “What kind of place is this?”

Miaozong replied, “All of the buddhas and patriarchs, and all of the great monks, came out from within this.”

Wanan asked, “Would you allow me to enter?”

Miaozong said, “Horses may cross, but not asses.” When Wanan was speechless, Miaozong declared, “The interview is over!” 4

The Song Literati

Another of Taizu’s innovations was to nurture a class of educated men called the shidafu, “scholar-officials” or “literati,” to fill the government’s bureaucracies. Although it was very rare for families not already in the upper classes to have the means to support a son through the years of study necessary to pass the exams, the advent of the exam system made it theoretically possible for even a child from a peasant family to become a high government official. More so than in the past, literacy was the key to upward mobility.

The rise of the literati combined with the invention (ca. 1040) of movable type created a culture that thrived on the written word. And Zen contributed its share, producing a considerable body of literature in this period. “Chan masters were very much aware that the publication and spread of its literature was essential for the success and survival of the Song Chan school and for their own careers,” writes the scholar Morten Schlütter. 5 Buddhism, and Zen in particular, was “an integral part of the intellectual environment of the Song-dynasty literati class.” 6

Zen and the Supernatural

Despite the intellectual and cultural achievements of Zen and other Buddhist schools, the dominant literary-philosophical movement of the Song was not Buddhism. It was a flowering of Confucian studies known in English as neo-Confucianism. Neo-Confucianism may have influenced one aspect of Zen that is especially attractive to many Westerners—its denial of the need for supernaturalism on the spiritual path.

Although we can question whether supernaturalism was ever needed in Zen, one does find it in earlier Zen, such as in the legends of Bodhidharma in the cave and in the story of Huineng and the robe and bowl that could only be lifted by the true patriarch.

One also occasionally finds comments attributed to this or that pre-Song Zen teacher mentioning the alleged supernatural powers of an enlightened being. In common with many other Buddhist schools, it appears that early Zen teachers took it for granted that enlightened beings have supernatural powers. (Although, in the case of Zen, exactly what those powers were or whether the master talking about them also had them was often not spelled out.)

In the ninth century, Guifeng Zongmi described five approaches to Zen, one of which was “outside the way” Zen that was concerned with using Zen practices to gain mental or supernatural powers. Zongmi taught that someone serious about realizing enlightenment should not bother with this lower-level sort of practice. It has to be noted, though, that he didn’t say people couldn’t gain supernatural powers through practice.

The scholar Steven Heine claims that Song dynasty Zen teachers felt pressure from the neo-Confucians to distance themselves from supernaturalism even further. “Leading Zen thinkers were in competition with the rational focus of the Confucian philosophers and needed to distance themselves from supernaturalism to forestall the critique of rationalist rivals,” he writes. This pressure would follow Zen into Japan, especially after neo-Confucianism gained influence there. 7

Transmission of the Lamp

Along with the many “extensive records” of great masters that we’ve already been discussing, two other types of Zen literature emerged during the Song: “Transmission of the lamp” records and koan collections.

Chuandeng lu, “Transmission of the lamplight records,” or sometimes just deng lu, “lamp record,” is the name for a genre of literature primarily known for its stories of pivotal encounters between ancestral teachers and the students who succeeded them. These texts also presented biographies, poetry, and sermons. The Song dynasty lamp records were published with imperial sanction; emperors sometimes wrote the prefaces.

The Jingde chuandenglu, “Transmission of the lamplight record of the Jingde era” or Jingde Lamp Record, compiled about 1004, is considered the prototype of all transmission records. It is a massive work, published in thirty volumes and containing more than 1,700 biographies—think of it as a comprehensive encyclopedia of Zen—and it reinforced the “tree and branches” lineage pattern established in the Patriarch’s Hall Anthology.

Albert Welter notes that these works “emerged from a dark period of Chinese history, seeking acknowledgment and recognition at a time when the Buddhist presence in China faced unprecedented challenge.” 8 Their publication was part of a campaign to win a place for the Zen tradition within Chinese culture. They presented a unified face to the Song establishment.

Welter goes on to say that the broader aim of the transmission literature was to define Zen orthodoxy: “They represent the constructed memory of Ch’an tradition expressing its most cherished aspirations.” 9 The stories in them presented not just wisdom but the unique identity of a tradition.

Further, Morten Schlütter explains, the authority of the Jingde Lamp Record “was such that to be considered a legitimate lineage holder in elite Chan Buddhism, it was imperative for a Song Chan master to be able to claim a direct link to an ancestor in it.” 10

The Five Houses of Zen

The many lineages of the Jingde Lamp Record were arranged into five houses. Scholars disagree whether the “houses” notion came before the Jingde Lamp Record or developed out of it. Although the houses sometimes are referred to as schools, in truth they were more like familial groups or clans. They differed more in style than in substance. It still was common for monastics to travel from one house to another to seek teachings. I want to mention them briefly only because they give us a picture of the Zen tradition at this point in its history.

The oldest of the five houses was Guishan Lingyou’s Guiyang house, which you might remember was also the spiritual home of the enlightened nuns Miaoxin and Liu Tiemo.

The Linji house of Linji Yixuan was best known for maintaining Hongzhou teachings, including the tradition of shouting, striking, and nose tweaking.

Caodong is the name of Dongshan Liangjie’s house. It’s commonly said that the name Caodong came from combining the name Dongshan with that of Caoshan Benji, one of Dongshan’s dharma heirs. However, Taigen Dan Leighton believes that the “Cao” in Caodong refers to Caoxi, the name of the creek that flowed past Huineng’s temple. Because of a tradition that gave teachers the names of geographic landmarks near their temples, Huineng was sometimes referred to as Caoxi.

The Yunmen house was named for Yunmen Wenyan (864–949), a fifth-generation dharma descendent of Shitou. Yunmen was the unfortunate fellow mentioned in chapter 3 whose leg was broken when a teacher slammed a door on it. Yunmen also was famous for his terse answers to questions, many of which became koans. For example, this is case 77 from the Blue Cliff Record :

A monk asked Yunmen, “What are the words that transcend the Buddha and the Patriarchs?”

Yunmen said, “Rice cake.”

The Fayan house was named for Fayan Wenyi (885–958), also a dharma descendant of Shitou Xiqian. This house gained many followers in the Ten Kingdoms but seems to have lost steam after the Song dynasty began.

Missing are the Oxhead and Heze (Southern or Shenhui) schools, which by the eleventh century had faded away.

Stories from the Jingde Lamp Record

Whether or not every anecdote in the Jingde Lamp Record has some profound spiritual message is a matter of opinion. I think some of them are merely meant to be amusing. For example:

Baizhang asked Huangbo where he had been.

“From the foot of Daxiong Mountain picking mushrooms,” replied Huangbo.

“Were there tigers to be seen there?” asked Baizhang.

Huangbo roared like a tiger; Baizhang laughed and pretended to attack him with an axe. Huangbo laughed and boxed Baizhang’s ear. Then Baizhang returned to the temple and addressed the assembly: “At the foot of Daxiong Mountain there is a big tiger; keep a watch out for him. Old fellow Baizhang has already been bitten today.” 11

Someone could frame this anecdote as Huangbo’s liberation from the authority of Baizhang or as Baizhang’s approval of Huangbo’s realization, but I don’t think it’s a huge stretch to simply see it as two guys goofing around.

Most stories in the Jingde Lamplight Record certainly do have a spiritual point, such as the story told in chapter 3 about the meeting of Nanyue and Mazu, when Nanyue polished a brick. We also find the story behind everyone’s least favorite koan, “Nanquan Kills the Cat”:

The monks of the eastern and western hall were arguing about a cat. Master Nanquan Puyuan said, “If there is a word forthcoming I will save the cat; if there is no word, then chop!” The monks were silent, and Nanquan killed the cat.

I would like to add here that we have no way to know that this really happened; do try not to be upset about the cat.

Later, Nanquan saw Zhaozhou and told him what had happened. Zhaozhou took off his sandals, put them on his head, and walked away. “Had you been there, the cat would have been saved,” Nanquan said. 12

In some versions of the story, Nanquan cut the cat in two, suggesting it would be divided between the two factions of arguing monks. Case 63 of the Blue Cliff Record tells us that Nanquan really didn’t kill the cat, however. (“The fact is that at that time he really did not kill. This story does not lie in killing or not-killing.” 13 ) As a koan, the story reflects a theme similar to that of Linji’s “true man of no rank” anecdote in chapter 4—if you have to stop and think about how to answer a question, you’re already wrong.

Encounter Dialogues and Their Origins

The scholar John McRae was the one who coined the term “encounter dialogue” to describe gongan, or the style of dialogue that developed in Song dynasty Zen. Although there are exceptions, the standard encounter dialogue as defined by McRae involves a brief exchange of words between a monk and a known teacher, usually of the Tang dynasty. No context is given for the exchange. And, to most readers, the dialogues are nonsensical. Scholars also often call the dialogues “iconoclastic,” although I’m not sure that’s the right word. Usually the dialogues don’t attack conventional thinking as much as ignore it.

For example, here’s a well-known one, preserved as case 38 in most translations of the Gateless Barrier :

A monk asked Master Zhaozhou, “Why did Bodhidharma come from the West?”

Zhaozhou said, “The oak tree in the garden.”

Note that it’s a cypress tree in some translations. What’s going on here? And how did this style of dialogue develop?

Victor Sogen Hori, a Zen priest and professor at the McGill School of Religious Studies, makes a strong case that this dialogue style arose from popular Chinese literary games. Part of the fun of the games was the use of allusion—speaking of something without mentioning it directly—to confound the other players. “And part of the skill of a good player was the ability to recognize the hidden meaning of the other person’s allusions and by ‘turning the spear around’ thrust back using a similar allusion with some other hidden meaning,” writes Sogen Hori. 14

Kōan after kōan depicts one Zen monk testing the clarity of another’s insight through the skillful use of allusion. The monks fiercely compete with one another not in the language of philosophical discourse but in poetic references to “coming from the West,” “three pounds of flax,” “wash your bowl,” and “the cypress tree in the front garden.” Mastery of the allusive language of Zen is taken as one of its marks of authority. 15

This also explains why the collections of dialogues were popular among the Song literati. And, frankly, their popularity among the Song literati no doubt encouraged Song teachers to collect and publish them.

In his book Tibetan Zen —about a school of Zen that flourished for a while in Tibet in the eighth century—the historian Sam van Schaik also has some ideas about encounter dialogues. Van Schaik bases his book on texts found in the Dunhuang library cave, and neither the Patriarch’s Hall Anthology , the Jingde Lamp Record, nor any other text containing Zen encounter dialogues were found there. The cave probably was sealed about the same time the Jingde Lamp Record was being compiled. Yet van Schaik does find Zen question-and-answer liturgies that took the form of staged conversations, such as the following:

The preceptor asks: What do you see?

Answer: I do not see a single thing.

Question: When viewing, what things do you view?

Answer: Viewing, no thing is viewed. 16

Van Schaik also points out that the Diamond Sutra, which is written in the form of a conversation between the Buddha and his disciple Subhuti, might be the ultimate encounter dialogue. This dialogue is a dance between relative and absolute, in which various phenomena—including the dharma itself—are reverently praised and then said not to exist. Our Song dynasty Zen monastics surely had studied the Diamond Sutra backward and forward.

I also would nominate the Oxhead school’s “Treatise on Extinguishing Cognition” as a forerunner of the encounter-dialogue style. You might remember that the text is written as a dialogue between Master Entranceinto-Principle and his student, Conditionality. Often, instead of answering Conditionality’s questions, Master Entrance-into-Principle points out the false assumptions behind the questions.

The difference in the later encounter dialogues is that the master doesn’t bother to point out the false assumptions. Instead, he might respond to the question the student should have asked or keep silent or give the student a smack with his whisk. If the student’s question assumes conventional thinking, the teacher’s response may reflect the absolute. If the student asks about the absolute, the teacher may point to the conventional.

Let’s go back to Zhaozhou’s oak (or cypress) tree in the garden. The question was, “Why did Bodhidharma come from the West?” This was a common question, it seems. In the Jingde Lamp Record we find:

A monk asked Master Daoqin, “What is the meaning of the Patriarch’s coming from the West?”

“On the mountains there are carp, on the seabed raspberries grow,” Daoqin said.

And again:

A monk asked, “What is the meaning of the Patriarch’s coming from the West?”

“Your question is not appropriate,” said Daoqin.

“Why is it not appropriate?” asked the monk.

“Wait until I am dead, and then I will explain it to you,” said Daoqin. 17

For the record, Jingshan Daoqin (714–92) was a master of the Oxhead school, although knowing that probably won’t help you understand the dialogues. There are several other examples of teachers answering the same question in several other ways, but these will do as examples.

The conventional answer to the question, of course, would have been “Bodhidharma came from the West to teach the dharma.” But how dead is that? It conveys nothing but concepts. It isn’t real. The skillful answers are, in one way or another, directly expressing reality instead of simply providing a concept. At the very least, they confound a mere intellectual understanding of the dharma.

Also, consider the question: Why did Bodhidharma come from the West? Or, what is the meaning of it? The question itself might suggest the student is looking for some big, secret, sparkly thing out there that will unlock a mystery. But that’s looking in the wrong direction. The teachers might have turned the question around and asked, “Why are you here? ” Ultimately, it’s the same question.

In various ways, these dialogues nudge us to let go of conventional thinking. In countless dharma talks on the oak tree in the garden, Zen teachers through the centuries have pointed to the reality of the oak tree. Don’t look for secret sparkly things, they say. There is nothing other than this oak tree, right here. Just this is it. But of course, the suchness of an oak tree is the entire cosmos.

Hopefully this background helps clarify the nature of the encounter dialogues, but the question remains—where do these stories come from? My impression as a writer, if not as a scholar, is that the Song dynasty record compilers probably were not inventing dialogues out of whole cloth, or at least they weren’t doing that most of the time.

We know that much note taking was going on during the Tang dynasty, even when students were told to not take notes. It’s said one enterprising monk made robes from paper to enable clandestine scribbling during sermons. It is from monastics’ notes that we have at least a few contemporary records of the Tang masters Huangbo Xiyun and Baizhang Huaihai. In places the Jingde Lamp Record gives the impression of a dumpster full of random papers—bits of commentaries, sermons, and poems, as well as scraps of dialogues—that someone carefully retrieved, uncrinkled, organized, and pasted into a scrapbook.

I also suspect that the compilers of the transmission of the lamp genre were not above pulling a pointer or a phrase out of an older document and building an anecdote around it. Occasionally you might notice that an anecdote about Master X is basically a tweaking of one about Master Y. Some of the stories might be based on monastic legends and folktales about the old masters.

And, yes, sometimes we find entirely new stories emerging in the lamp literature. According to Dumoulin, in the Jingde Lamp Record the Buddha signified transmission to his disciple Mahakashyapa by exchanging robes with him. But we find in the Tian sheng guang deng lu of 1036 that the Buddha silently held up a golden lotus, and Mahakashyapa smiled. Seeing the smile, the Buddha told the assembly, “I possess the true dharma eye, the marvelous mind of nirvana. I entrust it to Mahakashyapa.” This is the earliest known version of the flower sermon story, which is told to Zen students to this day. 18

The First Koans

Xuedou Chongxian (980–1052) was a master of the Yunmen house who liked to write commentaries. It was said that he had a strong Confucian education before he became a Buddhist monk, and he applied a Confucian appreciation of literary scholarship to his study of Buddhism. One day he asked his teacher, “The ancient masters did not produce a single thought—where is the problem?” The teacher hit Xuedou twice with his whisk, and Xuedou became enlightened.

Among the texts attributed to Xuedou is a collection of one hundred gongan to which Xuedou added his own verses as commentary. This was the Xuedou heshang baice songgu or “Xuedou’s verses on the old cases.” These were probably not the first collection of “old cases,” but these cases would become the basis of the first of the great koan collections, the Biyan lu, known in English as the Blue Cliff Record.

In 1125, Yuanwu Keqin (1062–1135), a master of the Linji house, updated Xuedou’s “old cases” with his own comments. He added a short introduction or pointer to most cases. After each of Xuedou’s cases, Yuanwu added a commentary. This was followed by Xuedou’s verse and Yuanwu’s commentary on the verse. Yuanwu also often added copious footnotes to Xuedou’s case.

The word koan is an English approximation of a Japanese rendering of the Chinese word gongan. Gongan literally means “magistrate’s table,” but it is often translated as “public case.” In Song China it referred to a legal precedent or an official judgment. Similarly, the Song Zen compilers drew on the precedents of Tang dynasty masters and the patriarchs.

The actual cases often are quite brief. For example, the two sentences, question and answer, in the “oak tree in the garden” exchange is the entirety of case 38 (in most editions; occasionally it’s case 37) of the Gateless Barrier. However, once the pointers, footnotes, commentaries, and capping verses are tacked on, there is a lot more to them.

The Gateless Barrier and a third classic Song Dynasty collection, the Book of Equanimity (also translated as the Book of Serenity ) were published roughly a century after the Blue Cliff Record, and a great deal happened in that century that requires explanation before we get to them.

The Early Twelfth Century: A Pivotal Time for Zen and the Song Dynasty

In 1101 the emperor Huizong wrote a preface to a lamp record called the Jianzhong jingguo xudeng lu. Of the five houses, he said, “Each has spread wide its influence and put forth luxuriant foliage, but the two traditions of Yunmen and Linji now dominate the whole world.” 19

Huizong’s reign had just begun in 1100. The emperor was a skilled painter and calligrapher and a generous patron of the arts. His capital in Bianjing, or modern-day Kaifeng in Henan Province, was a prosperous commercial and industrial center and may have been the largest city in the world at the time. And, because this was Song China, Bianjing was at the center of the most technologically advanced civilization of its day. By all accounts the city was a breathtaking wonder of exquisite temples, pagodas, canals, and parks.

Huizong was only a nominal supporter of Buddhism; writing a preface to an important lamp record simply was part of his job. His words reflected conventional views of the status of Zen at the time. By 1101, the Fayan and Guiyang houses had faded into extinction, and Caodong appeared to be critically endangered. Only Yunmen and Linji were thriving.

The fortunes of the Caodong house, however, were about to turn around. Indeed, even before Huizong wrote his preface, the Caodong revival had already begun.

The Caodong Revival

Touzi Yiqing (1032–83) was recognized as a scholar of the Avatamsaka Sutra before he began study with a teacher named Fushan Fayuan (991–1067), who had been a student of the respected Caodong master Dayang Jingxuan (943–1027). Dayang was the last Caodong master listed in the Jingde Lamp Record, and continuing his lineage was critical to the fading Caodong house.

It seems that Dayang approved of Fushan as a dharma heir—but there was a problem. Before becoming Dayang’s student, Fushan had received transmission from someone in the Linji house. Apparently there was a rule in place in those years that you can only be “transmitted” once; such is not the case anymore.

In order to maintain a link to Dayang, Fushan gave Touzi the portrait, shoes, and samghati robe of the deceased Dayang, and he told Touzi that the transmission from Dayang had been held “in trust” for him. To this day Touzi is considered the dharma heir of Dayang even though Dayang had died before Touzi was born.

There is great suspicion among the academic scholars that the preceding story was a fiction created to prevent the Caodong lineage from dying out. And maybe it was. It’s also possible that this was a perfectly acceptable workaround to a meaningless technical glitch. Touzi may have been in complete harmony with Dayang, for all we know.

Touzi’s dharma heir Furong Daokai (1043–1118) was a popular figure among Song literati, which considerably elevated the status of the Caodong house. In 1107, while he was leading a monastery in Bianjing, Daokai was honored with an imperial appointment to be abbot of the Tianning Wanshou Monastery, also in Bianjing. This was a temple that had been established by the emperor Huizong for his own merit, in which monks were required to pray for his longevity.

Daokai graciously thanked the emperor for the appointment, and then he declined it. The emperor sent the governor of Bianjing to persuade Daokai to change his mind. Daokai again refused the appointment.

Next came an official who warned Daokai that he would be punished if he continued to refuse. The official suggested that Daokai plead poor health as an excuse for the refusal, but Daokai said he felt fine. Soon enough Daokai was defrocked and sent into exile; it’s said people from all over Bianjing watched and wept as Daokai left the city. Daokai’s refusal of the appointment was understood to be a protest of the emperor’s religious policies.

Daokai traveled to his elderly father’s home in modern-day Shandong Province. The imperial order against him was lifted the following year, after an official sympathetic to Daokai interceded on his behalf. A local official helped him set up a monastery near modern-day Linyi, and there he taught for the rest of his life.

Daokai and another heir of Touzi, Dahong Baoen (1058–1111), had several dharma heirs between them. The Caodong house was saved.

The Ten Ox-Herding Pictures

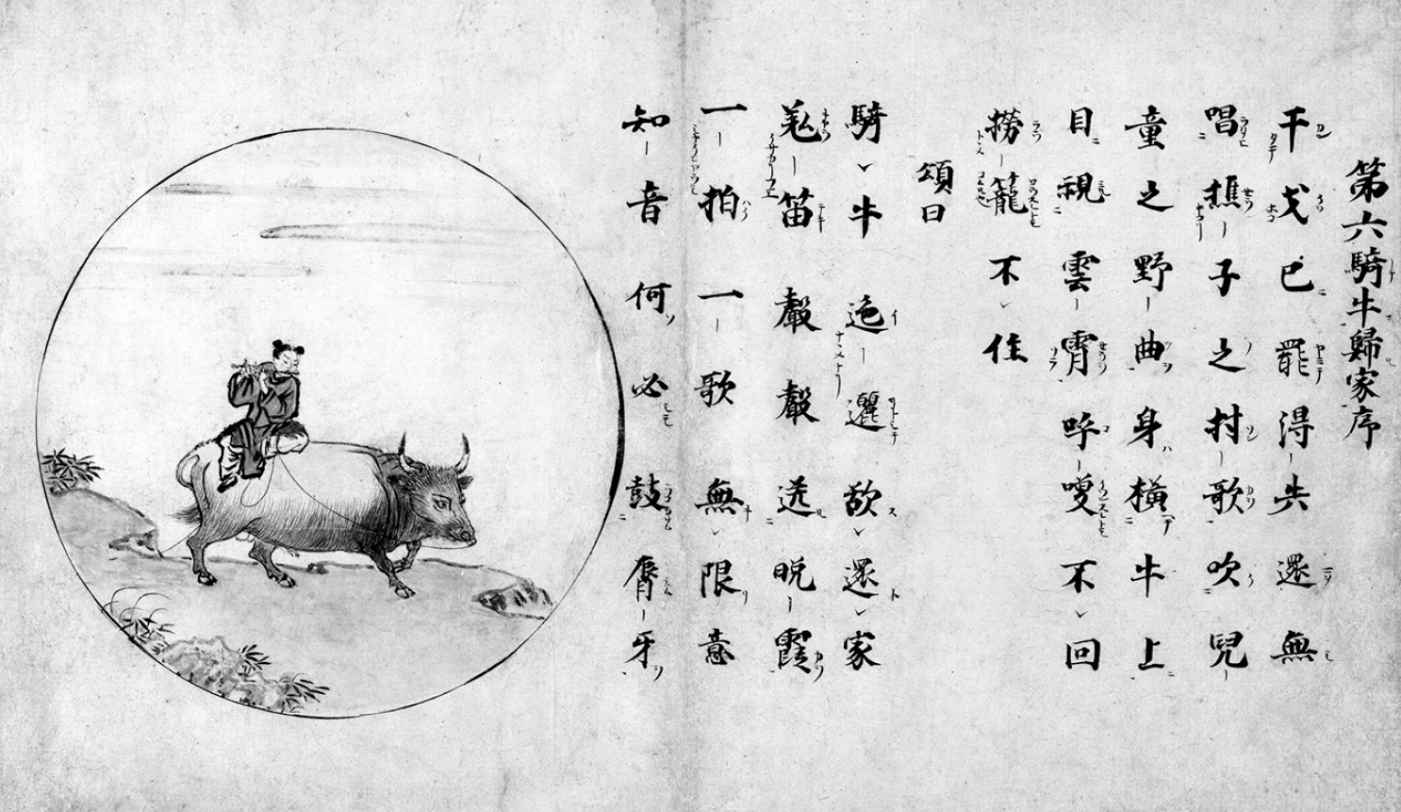

Today’s visitors to Zen centers and temples might notice a series of ten drawings involving an ox and a boy displayed somewhere. It was sometime in the twelfth century that a teacher of the Linji house, Kuoan Shiyuan (dates unknown) drew a series of ten pictures with accompanying verses called the Shiniu tu, or “ox-herding pictures.” Through a story of a boy and an ox, the ten pictures depict the path to enlightenment. There are other series of ox-herding pictures, but Kuoan is credited with first creating the sequence and verses most Western Zen students will recognize today. Through the years the ox-herding pictures have been redrawn in a variety of styles—including Japanese manga-style cartoons—by countless artists.

Figure 7. A portion of a Japanese scroll, dated 1278, of the ox-herding pictures and verses.

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Mary Griggs Burke Collection, gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation, 2015.

The sequence shows a boy looking for a bull ox, which represents his undisciplined mind. He finds and tames the ox and rides the ox home. Then he transcends the ox and the self and returns to the source. “Returning to the source” is often described as living in clarity, seeing reality exactly as it is.

In the final panel the boy appears as a happy old man with an unmistakable resemblance to Budai, the laughing buddha. In more traditional pictures, he is giving alms to a beggar who represents suffering. Master Sheng Yen writes, “He has left the isolation of the mountain and returned to the world to help all beings. He has no vexations, but because others suffer he spontaneously provides help on the path to all needful beings.” 20 Thus, the climax of the story is not transcending the world in a shining cloud of bliss but engaging with the world for the benefit of others.

The Fall of Northern Song

The emperor Huizong came to believe himself to be the younger brother of a celestial ruler of the Shenxiao school of Daoism, and he went about co-opting all Daoist temples to promote Shenxiao. Where there were no Daoist temples, local authorities were told to convert Buddhist temples to Daoist ones. Huizong also issued an edict for Buddhist monks to convert to the Daoist priesthood. For a brief time, in 1119 and 1120, Huizong attempted to have all of Song Buddhism assimilated into Daoism.

Despite his connections to celestial rulers, Huizong was not prepared for the crushing invasion of the Jurchen people from the north in 1125, about the time the Blue Cliff Record was published. Shortly before Bianjing fell in 1127, Huizong abdicated to his eldest son, the emperor Qinzong. Both emperors were captured by the invaders and spent the rest of their lives as hostages. The northern part of the empire collapsed into a smaller region south of the Huai River. Another son of Huizong escaped capture and became the emperor Gaozong. The Jurchen leader established the Great Jin Dynasty, which ruled much of northern China until 1234.

Historians refer to the preinvasion Song dynasty as Bei Song (northern Song) and the postinvasion dynasty as Nan Song (southern Song). During the Nan Song period, the court was less engaged in the running of monasteries. There was less governmental control and interference but also a great deal less financial support from the court. Temples became more dependent on local patronage, such as that of the local literati.

The Zen history of this transitional period is dominated by two teachers who had radically different ideas about Zen practice, Hongzhi Zhengjue of the Caodong house and Dahui Zonggao of the Linji house.

The Silent Illumination of Hongzhi Zhengjue

Hongzhi Zhengjue (1091–1157) was a dharma grandson of Furong Daokai. As a young monk he studied with several teachers, including Yuanwu Keqin (coauthor of the Blue Cliff Record ), before receiving transmission from Daokai’s student Danxia Zichun (1064–1117). Another of his teachers, Kuma Faqeng (1071–1128), became so still while meditating that, it was said, his body resembled dry wood. Hongzhi would also teach physical stillness while meditating.

Hongzhi taught for thirty years in Tiantong Monastery, located in present-day Ningbo, an ocean port city in Zhejiang Province. Hongzhi was a prolific writer with a devoted following among the literati. His poetry, formal sermons, and informal talks, instructions, sayings, and stories filled nine volumes of the Hongzhi lu (Hongzhi’s extensive record). He also compiled the cases presented in the next great collection of koans, the Congrong lu , or Book of Equanimity, published in 1224.

Hongzhi taught a form of meditation called mozhao chan, or “silent illumination chan.” Of the many writings Hongzhi left us about mozhao chan, the most frequently cited is the poem “Guidepost [or Inscription] of Silent Illumination” (Mozhao ming ), but there are many other commentaries about it in his “extensive record.”

Unfortunately for us, Hongzhi’s poems and commentaries fall short of being a meditation how-to guide. Students were presumed to be receiving instruction from a teacher. Hongzhi’s writings were poetic descriptions of meditation experience and commentary providing doctrinal context, possibly aimed at a wider audience than just Zen students. Still, we can learn a lot from what he wrote.

What Is Silent Illumination?

Early Buddhism identified two kinds of meditation, called in Sanskrit shamatha (“dwelling in peace”) and vipashyana (“clear seeing”). Shamatha techniques are about pacifying the mind and cultivating serenity, while vipashyana is about fostering insight. Hongzhi said that silent illumination represents a balance between the two. In his “Guidepost of Silent Illumination” he wrote that “if illumination neglects serenity aggressiveness appears,” and “if serenity neglects illumination, murkiness leads to wasted dharma.” 21 Mozhao chan, then, is about entering a serene illumination.

But illumination of what? Generally, meditation—Buddhist and non-Buddhist—focuses on something. The something might be an image, a visualization, a phrase, a sound, one’s breath, the Buddha. Something. But in mozhao chan one maintains awareness of the entire present experience. In this way, Hongzhi said, discriminating habits of mind fall away, including thoughts of achievement or merit. Even distinctions between “in here” and “out there” disappear.

Although this illumination is called “silent,” this is not the silence of a sensory deprivation tank. It is, instead, a profound openness, open inside and outside. Awareness of the entire present experience includes sounds, smells, and sights, experienced without attachments or judgments. “Everywhere sense faculties and objects both just happen,” Hongzhi wrote. “When you reach the truth without middle or edge, cutting off before and after, then you realize one wholeness.” 22

We see in Hongzhi’s descriptions of silent illumination the entirety of Caodong teachings going back to Shitou’s “Identity of Relative and Absolute” and “Song of the Grass-Roof Hermitage” and continuing through Caodong’s “Precious Mirror Samadhi” and the Five Ranks. When serenity and illumination balance and support each other, absolute and relative reflect each other. Form and suchness reflect each other. The particular and the universal reflect each other. Inside and outside reflect each other. The dualities merge of themselves.

“Box and lid [join] and arrow points [meet], harmoniously hitting the mark,” Hongzhi wrote, paraphrasing the “Identity of Relative and Absolute.” “Do not leave any traces and inside and outside will merge into one totality, as leisurely as the sky clearing of rainclouds, as deep as the water drenching the autumn.” 23

Hongzhi claimed that when this equilibrium is reached—“Spacious and content, without confusion from inner thoughts of grasping”—enlightenment is actualized. “When the stains from old habits are exhausted, the original light appears, blazing through your skull, not admitting any other matters,” he wrote. 24

Origins of Silent Illumination

Hongzhi expressed and expounded upon the practice of silent illumination in far more detail than anyone had done before. But much of what he taught is reflected in earlier sources, such as Hongren’s The Essentials of Cultivating Mind (mentioned in chapter 2), as well as in the work of earlier Caodong masters.

Going back even further, these meditation instructions from the Pali Suttapitaka are attributed to the Buddha:

When for you there will be only the seen in reference to the seen, only the heard in reference to the heard, only the sensed in reference to the sensed, only the cognized in reference to the cognized, then, Bāhiya, there is no you in connection with that. When there is no you in connection with that, there is no you there. When there is no you there, you are neither here nor yonder nor between the two. This, just this, is the end of stress. 25

I don’t believe the mozhao chan taught by Hongzhi or practiced today is exactly the same meditation taught by the Buddha. Yet a similarity is there, and likewise, there appear to be strong similarities between mozhao chan and other Buddhist meditations, such as a Tibetan meditation called mahamudra. This suggests these practices evolved from a common origin and that silent illumination is based on something people were doing a long time before Hongzhi taught it.

Dahui Zonggao and Huatou Contemplation

Dahui Zonggao (1089–1163) was Hongzhi’s contemporary, friend, and nemesis. A dharma heir of Yuanwu Keqin, in his day Dahui was the most respected Zen teacher in China. He received the title Great Master Buddha Sun from a high government official while he was only in his thirties, and like Hongzhi he had a devoted following among the literati.

Dahui had just received transmission from Yuanwu and was teaching in the north when the Jurchen invaded, forcing master and disciple to move south. In 1134 Dahui was living in a hermitage in Fujian Province, possibly seeking shelter from the continuing warfare. Or perhaps he just needed seclusion. While there, he began writing blistering denunciations of silent illumination Zen.

In brief, Dahui saw mozhao chan as too passive and not conducive to realizing enlightenment. For example, in 1149 he wrote in a letter, “The very worst [of all heretical views] is that of silent illumination, with which people become entrenched in the ghostly cave, not uttering a word and being totally empty and still, seeking the ultimate peace and happiness.” In Zen, the “ghostly cave” refers to a kind of meditative cul-de-sac that is very relaxing and pleasant but does not lead to enlightenment. It’s meditation as escapism.

In this criticism of silent illumination, Dahui also echoed Awakening of Faith. Practitioners of silent illumination did not appreciate the distinction between inherent and actualized enlightenment, Dahui said.

If everything is enlightenment, how could there be delusion? And if you say there is no delusion, how could it be then that old Śakyamuni suddenly was awakened when the morning star appeared and [he] understood that his own essential nature had existed from the very beginning? Therefore, it is said that with the actualization of enlightenment, one merges with inherent enlightenment. 26

In 1141 Dahui was defrocked and sent into exile in Hunan Province. This was possibly because of his association with a member of the literati who opposed the government’s policies toward the Jin dynasty. Or it may have been because his criticisms of other Buddhists annoyed the emperor. While in exile he continued teaching and writing, and he continued to speak out against silent illumination practice.

In 1155 Dahui was forgiven by the emperor, and the following year he became abbot of a temple at Mount Ayuwang in Zhejiang, which was very near Hongzhi’s Tiantong Monastery. Despite Dahui’s well-known criticisms of silent illumination, the two teachers became friends and referred students to each other. In time Dahui was reassigned to another temple, but shortly before he died Hongzhi requested in his will that Dahui take charge of his affairs.

Zen teachers today point to Dahui and Hongzhi’s friendship to argue that Dahui was not critical of silent illumination per se; he merely criticized people who weren’t doing it right. In his book How Zen Became Zen, however, Morten Schlütter makes a strong argument that Dahui was in fact attacking silent illumination and the entire Caodong house with it. 27

A side note: It is sometimes assumed that the contention between Linji and Caodong—which never entirely resolved—is a continuation of the sudden versus gradual controversy between Northern and Southern Zen from the early Tang dynasty. Some academic works identify Mazu-Linji lineage teachers with the Southern “sudden” school and assume that Caodong is a continuation of the Northern or “gradual” school. This is not how the Caodong school ever saw itself. All schools of Zen that survived the Tang dynasty consider themselves to be the heirs of Huineng. Further, Dahui’s beef with silent illumination, although superficially similar, does not seem to me to be identical to Shenhui’s disagreement with the heirs of Shenxiu. But fully arguing this point would require another book.

Kanhua Chan: Huatou Contemplation

In place of mozhao chan, Dahui taught what later came to be called kanhua chan, or “Chan of investigating the topic of inquiry.” This meant using gongan as objects of meditation.

Teachers before Dahui taught students to contemplate gongan in the sense of mulling over what they might be expressing. The gongan stories had been included in sermons and commentaries from the beginning of the Song dynasty. But Dahui made the gongan into an object of meditative inquiry.

Dahui and his followers would extract the essential point or critical phrase from a gongan and use it as an object of concentration meditation. This essential point is the huatou, or the crux of the gongan.

Dahui’s huatou meditation differed from the koan contemplation of the later Rinzai Zen school, with which most Western Zen students are more familiar. In Chinese Chan, huatou practice is not about arriving at an answer and then moving on to the next case, as is done in Rinzai Zen. Instead, a Chan practitioner might work with just one huatou all his or her life, going deeper and deeper. In contrast, later Rinzai Zen would develop a koan curriculum that takes students through hundreds of koans.

As Dahui described it, huatou meditation begins when a gongan stirs the student’s interest, which Dahui called “taste” (wei ). This is something like the pivotal moment of Dongshan’s “Precious Mirror Samadhi,” and it’s a moment of shimmering potential. It’s a strange, intriguing shape on the horizon that you can’t quite make out or a movement spotted in the depths of a lake. What is that? You are compelled to investigate; you will have no rest until the mystery is solved. The student who relates to the gongan as if it were just a trick question wanting a glib answer isn’t ready for huatou.

But this taste soon leads to doubt (yiqing ), because the gongan cannot be understood intellectually. Trying to figure out what the gongan is saying leaves the student frustrated—“as if you were gnawing on an iron rod,” Dahui said. Intellectual means exhausted, the student sits with the huatou, the critical phrase or keyword of the gongan, letting it sink into deep places beyond the reach of conceptual thought. Eventually the huatou pervades her being. The strange, intriguing shape on the horizon isn’t out there ; it’s in here, and it’s also everywhere.

Great Doubt

The English word doubt usually means something like distrust or a hesitancy to believe or accept. In early Buddhism, doubt (in Pali, vicikiccha ) was one of the five hindrances that got in the way of practice (the other four are sensual desire, ill will, sloth, and restlessness). Vicikiccha is sometimes translated “skeptical doubt.” The Buddha compared a monastic infested with doubt to a wealthy merchant crossing a desert full of bandits, leaving him anxious and unsure which route to take. 28 The antidote to this doubt is trust, especially in the Buddha, the dharma, the sangha, the practice, the past, the future, and conditions.

The Chinese word yiqing suggests more of a sense of puzzlement than of fearful anxiety or skepticism. But what begins as puzzlement becomes an intense not knowing that grows to engulf the student’s entire being. “Ordinary doubt is directed at some external object such as the koan itself or the teacher, but when it has been directed back to oneself, it is transformed into Great Doubt,” writes Victor Sogen Hori. 29 Sheng Yen asserts that Great Doubt does not mean skepticism or suspicion but “an intense unease and wonderment” that becomes an all-consuming questioning. Dahui said that the doubt centered in the huatou becomes like a hot metal ball one can neither swallow nor spit up.

Some academic historians have worked to reconcile the apparent clash between “bad” doubt in early Buddhism and “good” doubt in Song dynasty Zen. There are theories that there is something about Chinese culture that caused this doctrinal shift. I think this is overcomplicating the issue because it seems to me that vicikiccha and yiqing are two different things. That they both end up translated as “doubt” says more about the imprecision of English than any doctrinal shift.

Further, it takes a great deal of trust —in the dharma, in the practice, and so on—to be able to engage in this intense investigation. To return to the Buddha’s analogy of a rich merchant crossing the desert, if the merchant is filled with Great Doubt, he’s not frozen with vicikiccha and looking over his shoulder for bandits. He is fearlessly questioning the nature of his own existence.

Common Chan huatou includes such questions as “What was my original face before I was born?” and “Who is dragging this corpse around?” And then there’s the one about the dog.

Zhaozhou’s Dog: The Great Wu

Most Western Zen students will recognize the Chinese Wu as the Japanese Mu. Dahui recommended the huatou Wu, which was extracted from a gongan called “Zhaozhou’s Dog.”

Three versions of “Zhaozhou’s Dog” emerged in the Song dynasty. The first one appeared in the Jingde Lamp Record. The second was collected by Hongzhi and would be published as case 18 in the Book of Equanimity . The third and best-known version would become the first case in the Gateless Barrier . The basic case:

A monk asked Zhaozhou: Does a dog have Buddha Nature, or not?

Zhaozhou said, “Wu! ”

Sometimes Wu/Mu is left untranslated, but basically it signals negation and is commonly translated as “Not!” “No!” or “Does not have!”

Why Wu ? Bedrock Mahayana doctrine says buddha-nature permeates all beings, and dogs do qualify as “beings.” But to ponder this gongan in terms of the dog or any other living creature existing as a stand-alone thing that possesses (or not) the extant quality “buddha-nature” means someone hasn’t been paying attention. Yet a great many academic Buddhologists have declared that Zhaozhou was merely weighing in on whether animals did or did not possess buddha-nature as humans do.

No, academic Buddhologists, that will not do. How do we understand “beings”? How do we understand buddha-nature without falling into the atman/Brahman heresy? How do we inject buddha-nature into the dog, or the Zen student, without assuming the singular and continual existence of everything named in this sentence, which Madhyamaka denies?

I realize there probably were Buddhists in China pondering whether the Awakening of Faith model that connects buddha-nature with storehouse consciousness applied to animals, since it had long been believed that only beings born into the human realm could enter nirvana. But such a mechanical and purely phenomenal conceptualization of reality clearly is out of place in Zen.

This is illustrated by the Jingde Lamp Record version of “Zhaozhou’s Dog.” After enquiring about the dog and being told that yes, the dog has buddha-nature, the monk asks Zhaozhou, “Do you have Buddha Nature?” And Zhaozhou says no. And why not? “Because I’m not a thing,” the master replies.

In the Book of Equanimity version, two monks on two separate occasions ask Zhaozhou the dog and Buddha Nature two questions, and Zhaozhou says “has” or “yes” to the first monk but “not” or “no” to the second. To grossly oversimplify many deep and subtle commentaries, in this version Zhaozhou is balancing the absolute and relative natures of existence. The question presented in “Zhaozhou’s Dog” isn’t so much about a doctrine of buddha-nature as it is about the nature of being.

Dahui said that Wu “is a knife to sunder the doubting mind of birth and death.” Don’t hold on to birth and death and the Buddha path as existent, he said. Do not deny them as nonexistent. Don’t be concerned with awakening or not awakening. Make no distinctions; don’t objectify anything. Just contemplate Wu. Put the mind and Wu together until the mind has no place to go. And then, “suddenly, it’s like awakening from a dream, like a lotus flower opening, like parting the clouds and seeing the moon.” 30

As is explained repeatedly in Zen commentaries and dharma talks, language cannot be relied on. Language is built on conceptualization—especially, as we now know through evolutionary biology, how the human brain evolved to decipher and navigate reality. It does this by slicing reality into pieces that become nouns and predicates and objects, connected by verbs, conjunctions, and prepositions. When we put reality together again, we find ourselves in a place where language no longer functions. Even the Buddha could not describe it. So the old teachers fell back on poetry and allusion. “Parting the clouds and seeing the moon” is about as close as anyone can get.

Having had this experience, is the student enlightened? Well, the student already was enlightened; it cannot be emphasized enough that enlightenment is not a quality that some people possess and others do not. In many ways, this first breakthrough is not the end of path but the beginning. It’s sometimes said that this first breakthrough correlates to the first of Dongshan’s Five Ranks. Teachings that seemed nonsensical before will clarify, but some haze will remain. This is why Wu has been called the “barrier gate”: once through it, there is more to be realized, but insight becomes possible that wasn’t possible before.

These “opening” experiences are called many things, but it’s most important to keep in mind that they are not exclusive to huatou practice or Zen or even Buddhism. Huatou is simply one method that has been found to be effective for bringing them on.

The rivalry between mozhao chan and kanhua chan persists to this day. Many of us who have practiced both can tell you that the methodologies each have strengths and weaknesses. Choosing which is better is an individual matter. Practitioners of both do experience the actualization of enlightenment, and likewise, practitioners of both do run into difficulties. The goal-oriented practice of solving koans can cause some to lose sight of Mazu’s ordinary-mind teachings (never mind that “ordinary mind” is itself a koan). Silent illumination, when not understood, can become nothing but a stress-reduction technique. Put another way, a one-sided devotion to koan contemplation “can become arid, intellectual, and disconnected from reality,” writes James Ford. “And a one-sided attachment to a just-sitting practice can slip into torpidity, into a mere quietism.” 31

The End of Buddhism in India

By the Song dynasty, Chinese Buddhism was long past looking to India for instruction. But before we move on to thirteenth-century China, let us pause to note the passing of Buddhism from its original home on the Ganges plain.

Buddhism had been slowly fading in India for a long time, primarily because it had become insulated and removed from the lives of most of the people. Hinduism and Jainism were by far the more dominant traditions in Buddha’s homeland. By the twelfth century most of what remained of Buddhism on the Indian subcontinent was concentrated in three large monasteries and learning centers in what is now the Indian state of Bihar—Nalanda, Odantapuri, and Vikramashila—and in two more, Somapura and Jagaddala, that were located on the lower Ganges in what is now Bangladesh.

Of these, Nalanda is best remembered today as a great seat of learning, and not just about Buddhism; it has been called the world’s first university. Several of the early masters of Indian Buddhism were associated with Nalanda. Shantideva first recited the Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life there and was said to have floated away to the skies as he spoke the final verses. Many of the significant early teachers of Tibetan Buddhism studied there and took Nalanda Buddhism to Tibet. Nalanda was past its prime by the twelfth century, but students from many parts of Asia still went there to be educated.

In about 1193, Bihar was invaded by a Turkic army led by a general named Muhammad Bakhtiyar Khilji. The assault came as one among numerous waves of Muslim attacks against India, launched initially from the Arabian Peninsula and later by Islamic kingdoms and armies from the regions of modern-day Turkey, Afghanistan, and elsewhere in central Asia. When the general learned of a great library nearby, he sent a messenger to Nalanda to inquire if the library contained a copy of the Quran. When told it did not, he ordered the entire complex to be destroyed. It was, and everyone found at Nalanda was slaughtered.

The library at Nalanda was the largest repository of Buddhist chronicles, scriptures, and other texts in the world. No doubt many records and other documents were stored there that had never been copied. Burning it all took several months. It’s said dense smoke from the fires settled over the land for a very long time.

Meanwhile, Odantapuri and Vikramashila were similarly destroyed. Monastics who could escape fled south or made their way to Nepal or Tibet. About a decade later Muhammad Bakhtiyar Khilji took armies into the lower Ganges and burned Somapura and Jagaddala and any smaller monasteries he could find. Buddhism disappeared from the subcontinent. In time, people forgot it had ever been there.

A series of Muslim sultanates would rule most of the Indian subcontinent for the next several centuries. In the fourteenth century one of the surviving Ashoka pillars, its script unreadable and its origins forgotten, was used to support a minaret near Delhi.

The Book of Equanimity

Yelu Chucai (1190–1244) was a Confucian scholar who, at the age of twenty-eight, became an adviser to Genghis Khan. Yelu was an ethnic Khitan born in the north, in Jin dynasty China. When Mongols invaded Jurchen territory in 1211, many Khitans sided with the Mongols, and Yelu—said to be nearly seven feet tall, with an impressive beard and deep voice—favorably impressed the great khan. Yelu is remembered for advising the Mongols not to slaughter captured populations but to rule them.

Although we’ve been focused on southern Song dynasty Zen, there still were Zen monasteries in the former northern Song territory that had been taken over by the Jurchen. Wansong Xingxiu was a Caodong teacher serving as abbot of a monastery near what is now Beijing, then called Zhongdu, which was the Jin dynasty capital. In 1215 Zhongdu was taken by Mongol armies, and the Jin court fled. But Wansong remained in his temple.

In 1223, Yelu Chucai went to Wansong with a request. Would he expound upon the one hundred old cases that had been collected by Hongzhi Zhengjue? Wansong added introductions, commentaries, and capping verses to Hongzhi’s cases. The result was the Congru lu —which, as previously noted, is translated as the Book of Equanimity or the Book of Serenity, although its literal translation is closer to “encouragement (hermitage) record.” The Book of Equanimity and the Gateless Barrier are today considered the two most important collections of classic koans, with the Blue Cliff Record a close third.

What are we to infer from the fact that an important book of koans was produced by the Caodong school—supposedly the school of silent illumination? Remember that the encounter-dialogue stories had been collected and enjoyed by practitioners of all the Zen houses beginning in the tenth century, and Dahui didn’t promote huatou contemplation until the twelfth century. The old cases never belonged exclusively to the Linji school.

The Gateless Barrier

It’s said that Wumen Huikai (1183–1260) of the Linji house worked on the Wu huatou for six years before it was resolved. Sometimes he even walked the temple halls at night and knocked his head against the pillars. One day, when a drum announced the noon meal, he broke through. He marked the occasion with a poem:

A thunderclap under the clear blue sky

All beings on earth open their eyes;

Everything under heaven bows together;

Mount Sumeru leaps up and dances. 32

Mount Sumeru is another name for Mount Meru, which is the mountain at the center of the universe in old Indian cosmology.

After receiving transmission, Wumen let his hair and beard grow and wore shabby robes, and he worked in the monastery fields with junior monks. His students called him “lay monk” because of his lack of priestly airs.

In 1228 Wumen was leading a monastic training period, and at the request of the monks he gave a series of lectures on forty-eight cases taken from the transmission of the lamp literature, beginning with “Zhaozhou’s Dog.” The collection, with Wumen’s introductions, comments, notes, and capping verses, was published in 1229. An additional case was added in 1246.

The title, Wumenguan, means “gateless barrier” or “gateless checkpoint” or “Wumen’s checkpoint.” The common alternate English title Gateless Gate appears to have originated from an early English translation by Nyogen Senzaki, published in 1934, and it stuck. Japanese Zen teacher Koun Yamada (1907–89) also used the odd title in his English translation and argued that the self-contradictory “gateless gate” is a koan in itself. Most English-speaking Zen teachers seem to prefer “gateless barrier” or variations thereof.

The number of English translations of the Gateless Barrier, often with fresh commentary, is a testimony to its significance. I can’t think of another classic Zen text—not even the Platform Sutra—that is more available to English speakers. I can personally recommend Robert Aiken’s The Gateless Barrier (New York: North Point Press, 1990), Zenkai Shibayama’s Gateless Barrier (Boulder: Shambhala, 2000), Koun Yamada’s The Gateless Gate (Boston: Wisdom, 2005), and Guo Gu’s Passing Through the Gateless Barrier (Boulder: Shambhala, 2016).

The End of the Song Dynasty and Formulation of the Three Essentials

With enthusiastic help from the Nan Song dynasty, by 1234 Ogedei Khan, third son of Genghis, had entirely conquered the territory of the Jin. All of China north of the Huai River was now under Mongol control. A year later, the Song foolishly tried to reoccupy former northern Song cities, a move that displeased the Mongols. The alliance ended, and the Mongols began a long campaign to conquer the Song.

Ogedei’s nephew Kublai was elected great khan in 1260, and Kublai Khan defeated the last holdouts of the Song in 1279. Rather than surrender, a high-level minister named Lu Xiufu took the eight-year-old Zhao Bing, the last emperor of the Song dynasty, into his arms and leaped off a cliff into the sea.

Kublai Khan became ruler of China and established the Yuan dynasty. Mongol rulers had been patrons of Tibetan Buddhism, and Kublai and his successors were supportive of Chinese Buddhism as well.

At about the time Kublai Khan assumed rule of China, a distant dharma descendent of Dahui’s named Gaofeng Yuanmiao (1238–95) elaborated on Great Doubt by calling it one of the three essentials to kanhua practice. Great Faith was the first essential. This faith is closer in meaning to trust, confidence, or commitment than belief; it is confidence in yourself and trust in and commitment to the practice. Next is Great Ferocity, described by Gaofeng as attacking the huatou with as much energy as if you had found the villain who murdered your father. And the third essential is Great Doubt.

Eventually someone must have decided that Great Ferocity was a little too fierce, and the three essentials became Great Faith, Great Doubt, and Great Determination—the formulation in which they are taught today. Some versions also add, Great Vow.

Zen in China had survived another dynasty, and it would survive a few more. There would be more developments and many celebrated teachers. But for the most part, the Zen that China gave the world was Song dynasty Zen. In keeping with the original purpose of this book—to tell the story of how Zen came to be what it is today, as succinctly as possible—we will now leave China to follow Zen’s story elsewhere.