6

“ORTHODOXY. AUTOCRACY.

NATIONALITY”

Timeline

| 1812 | Napoleon’s invasion of Russia |

| 1826–8 | Russo-Persian War |

| 1828–9 | Russo-Turkish War |

| 1853–6 | Crimean War |

| 1855 | Death of Nicholas I |

| 1861 | Emancipation of the serfs |

| 1881 | Assassination of Alexander II |

| 1904–5 | Russo-Japanese War |

| 1905 | Revolution |

The Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, Moscow

© Mark Galeotti

Within view of the Kremlin, the white-walled and gilt-domed Cathedral of Christ the Saviour was originally conceived by Alexander I to celebrate Russia’s victory over Napoleon. It was to be a neoclassical structure, reflecting the style dominant in the West at the time. The original site proved unsuitable, though, so his son, Nicholas I, decreed that the cathedral would instead be built where it is now, but he favored a more traditional style, evoking Russian traditions and the glories of the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. The outer structure was completed under Tsar Alexander II, who largely ignored the project, and the cathedral was finally consecrated in 1883, on the eve of the coronation of Alexander III. It would later be dynamited under Stalin and rebuilt in the 1990s, largely to Nicholas’s original design.

In granite, marble and 20 tons of gold, the church is a metaphor for changes in politics and priorities over the years. Alexander I wanted to show that Russia was rich enough and European enough to be able to build a towering edifice that matched the tastes of the times. Nicholas I wanted to demonstrate that Russia didn’t need to keep up with the neighbors, and could cleave to traditional styles and imperial aesthetics. Alexander II was busy and not especially concerned with churches, but rather factories, courthouses and schools.

Should Russia simply try to look like the equal of a Western power, without actually trying to be one? Should it stick to its own ways? Should it try and grasp the essence of modernization, rather than just the appearances? Napoleon’s invasion of 1812 was defeated by logistics and demographics, but Russia convinced itself that its ability to weather his advance and join the counteroffensive proved that it was stronger than everyone had assumed. This was a perfect excuse to justify putting off the social, political and economic modernization that Russia desperately needed. Any reforms would inevitably bring with them uncertainty and unrest, after all, as Alexander II’s reign was to demonstrate.

The nineteenth century was, therefore, one of competing myths, each of which directly bound Russia with Europe. To reformers, it needed to be more Western. To conservatives, Russia needed to reject the West, lest chaos be unleashed. Meanwhile, revolutionaries were increasingly looking to ideologies being elaborated in Europe and seeing in them magical solutions that could somehow leapfrog Russia into the forefront of the socially and economically advanced nations of the West. Unwilling to accept the changes reshaping Europe, unwilling to accept exclusion from Europe, Russia was being torn apart by the contradictions in the stories it told itself about itself.

General Winter and Mother Russia

Much of Russia’s nineteenth century would be defined by Napoleon’s decision to invade in 1812. The war that followed—called the “Patriotic War” by the Russians—was a terrible one for them, and consequently the victory that followed was a transformative one. Alexander I (r. 1801–25), the tsar whom one of his contemporaries said “knocked at every door, so to speak, not knowing his own mind,” had first turned against France, then with it, in an alliance of inconvenience that had foundered in 1810, as Napoleon failed to keep his promises to help Russia against the Ottomans. The French emperor was a man who could not stop for either personal or political reasons, so in 1812, in a fateful act of hubris, he led his Grande Armée, the largest expeditionary force the world had ever seen, into Russia. It was time, Napoleon purportedly said, “once and for all to finish off these barbarians of the North,” who “must be pushed back into their ice, so that for the next 25 years they no longer come to busy themselves with the affairs of civilized Europe.”

Napoleon’s army of French veterans, Polish lancers, Austrian riflemen and Piedmontese sharpshooters would be broken in Russia. In part this was down to the stubborn resistance of the Russians but also thanks not only to the country’s traditional ally, “General Winter,” but the sheer size of Mother Russia’s bounds. Faced with an enemy able and willing to take fullest advantage of strategic depth and withdraw before his advance, burning crops and spoiling wells on the way, Napoleon became increasingly infuriated that the Russians simply weren’t willing to play by his rules. Finally, at Borodino, the Russians stood and fought, losing perhaps a third of their army to withering barrages of cannon fire in the bloodiest day of fighting of the Napoleonic Wars. Yet they retreated in good order. The Russians even abandoned Moscow, but refused to surrender.

Napoleon brooded in Moscow for a whole month, sure that the Russians would sue for peace. When they did not, as the stocks of food for his men and fodder for his horses ran lower and lower, he was forced to retreat. Harried by Cossack hit-and-run raids, ambushed by angry peasants, ravaged by hunger and disease, the Grande Armée shrunk with every pace of its retreat, while Napoleon spurred ahead of them to Paris, desperate to secure his position and spin the defeat as a victory. Of the 685,000 men who marched into Russia, only some 23,000 stumbled out alive.

The war was not over, but momentum had swung against Napoleon. Seeing the opportunity for victory, Prussia and Austria joined Russia in rolling westward, and the Duke of Wellington led his British, Spanish and Portuguese forces across the Pyrenees into France. In 1814, Napoleon abdicated and left for exile in Elba (from which he would briefly return in 1815, but that’s another story), France was sheared of 20 years of gains, the tsar could add portions of Finland and Poland to his empire, and Russian officers could toast their victory on the Champs-Élysées.

After the Antichrist

Before the war, the ever-inconstant Alexander had first toyed with reform, even daring to propose candidates for higher government positions ought to sit exams, before falling under the influence of Count Alexei Arakcheyev. A ruthless zealot of predictably bad temper and unpredictably vicious whimsy—he would weep at the beauty of nightingales’ song and then have all the cats in the neighborhood killed so they did not prey on them—Arakcheyev encouraged Alexander to embrace the mystical messianism of his father. The French Revolution had unleashed a wave of radicalism in Europe and in due course the rise of Napoleon. In Alexander’s mind the consequent anarchy threatening Europe came to seem an almost satanic threat (he became fixated by the news that a Russian scholar had proved through cabalistic numerological analysis that the letters in the phrase “L’Empereur Napoléon” added up to 666, the “Number of the Beast”), and victory a triumph of righteous order.

It also seemed to reaffirm the strength of the Russian state. The eighteenth century had been dominated by concerns about how to modernize, how to catch up with the West—and how dangerous this might be for the existing order. Would the rise of “new men” within the government apparatus supplant the aristocracy? Would the spread of education further revolutionary sentiment? Victory over Napoleon became a convenient myth of the system’s fundamental health. After Borodino, Napoleon wrote that “the French showed themselves to be worthy of victory, but the Russians showed themselves worthy of being invincible.” Arguably this was a poisonous bequest to his conquerors: dangerous is the day any regime tries to convince itself of its own invincibility.

Doubly so when some of its best and brightest are drawing the very opposite conclusions. Since Catherine’s day, French language, literature and ideas had been considered the very peak of sophistication. Many young officers, drawn from the educated elite, had been enthused by the ideals of the revolutionary age, and then exposed to them in France. The early years of Alexander’s reign had generated hopes that change was coming to Russia, hopes the subsequent conservative reaction had dashed. Secret societies, radical factions and conspiratorial movements bubbled away beneath the orderly surface of the regime, some advocating constitutional monarchy, others outright republicanism. By the 1820s, they had found common cause in concluding that their only hope of change was in a violent coup. They even set a date, for December 1825.

Then Alexander had the poor grace to die, of typhus, just under a month before they were ready to strike.

The Soldier Tsar

Why let a good plot go to waste, though? They decided still to go ahead with their plan, just as the new tsar Nicholas I (r. 1825–55) was being crowned, and in the process ensure that his reign would be devoted to an undeviating defense of the status quo. Russia’s story is full of such tragic ironies.

Nicholas had not even been meant to be tsar. Alexander left no legitimate heirs but two brothers. The younger, Nicholas—Nikolai—had instead trained as a soldier because Grand Duke Konstantin, governor of Poland, was next in line. But Konstantin married a Catholic Polish countess in 1820, and thus had secretly surrendered his claim to the throne. Dutiful, energetic and unimaginative, Nicholas then accepted the crown just as the liberal conspirators rushed to try and seize the initiative. What became known as the Decembrist Revolt of 1825 saw some 3,000 young army officers and their fellow travelers take to the streets in St. Petersburg. They demanded a constitution, they wanted reform, they got Nicholas. Cannon blasted them out of Senate Square, and loyal troops rounded the survivors up at bayonet-point, most ending up exiled to Siberia. The new tsar would come to power in battle, and from the first saw his role as being a soldier in the frontline against anarchy and insurrection. He saw no contradiction between his view that an autocrat had to be “gentle, courteous and just,” and building a police state and ruthlessly suppressing liberal writers and radical thinkers alike.

He looked at the empire as he would at an army. Just as an army needed discipline, so too did a nation, and at a time of revolutionary sentiment, it needed something to hold it together. In the wake of the Decembrist Revolt, which was considered in part a product of dangerous, foreign-inspired freethinking among the educated young, it fell on Count Sergei Uvarov, as education minister, to provide an answer. In 1833, he proposed the notion of “Official Nationality,” a doctrine that claimed that Russia’s traditional values needed to be defended against alien notions. The formula that was adopted was “Orthodoxy. Autocracy. Nationality.”

Leaning on Russia’s role as the last true Orthodox state was nothing new, but after a century of lip service to the idea of getting beyond tradition and embracing Western rationalism, this became a justification for quite the opposite. “Europe” was now a source of contamination that Nicholas said was “in harmony with neither the character nor the feelings of the Russian nation.” God meant Russia to be Russia, not a pallid copy of Western Europe. This was the job of autocracy, undiluted by constitutionalism. This did not mean tyranny for its own sake but what one could call, in contrast with Catherine’s ideal, unenlightened despotism: rigid central power in the name of the common interest. In the pursuit of national unity and a single loyalty, all subjects of the tsar should embrace a single faith and values. This was an era of “Russification,” as the Catholic Church in Poland came under new restrictions and Poles, Ukrainians, Lithuanians and Bessarabians were pressed to learn Russian.

Astolphe-Louis-Léonor, Marquis de Custine, was a liberal French aristocrat who traveled through a Russia that clearly appalled him, and he opined that “This empire, vast as it is, is only a prison to which the emperor holds the key.” The irony was that the tsar who has largely gone down in history as the epitome of the unreasoning martinet, the humorless defender of a dying and despotic order, was actually deeply skeptical of it. He genuinely believed in his divine right to rule, but believed that this required him to be hardworking, mindful of his responsibilities to Russia and the divine. He created the Special Corps of Gendarmes and the fearsome political police of the Third Section of His Imperial Majesty’s Own Chancellery, both under General Count Alexander Benckendorff, but genuinely saw them as protectors of the people, policing them for their own good. Nicholas notoriously gave Benckendorff a handkerchief with the enjoinder to wipe away the tears of his subjects. He also oversaw a regime of censorship that often verged on the farcical—in some cookery books, references to “free air” were excised as sounding too subversive, and both Alexander Pushkin and Fyodor Dostoevsky, greats of the Russian literary canon, would fall foul of the Third Section—but which was nonetheless seen as essential to hold back the tide of destructive ideas from the West.

He was not a self-indulgent tsar, and over time became increasingly disenchanted with the triviality and pomp of court entertainments. He certainly had no illusions about the aristocracy: according to legend, he told his ten-year-old son Alexander, “I believe you and I are the only people in Russia who don’t steal.” Indeed, his reign was noteworthy for the proliferation of generals appointed to ministries and Baltic German aristocrats (like Benckendorff) from the empire’s northwestern margins elevated to key positions: he felt he had to go outside the usual pool of officials and noblemen in the hope of finding honest and efficient personnel. Sadly, that often didn’t work, either.

Most strikingly, Nicholas also disapproved of the institution of serfdom. Through his reign, he would convene a series of secret commissions to try and find some way of squaring the circle: how to abolish a system of land-slavery that was inefficient, inhumane and a source of periodic uprisings without totally destabilizing the whole social order and alienating the rural gentry, the landlords who were the backbone of the tsarist order in the countryside. Nicholas was brave enough faced with physical danger, but he never dared tackle this challenge, concluding that “There is no doubt that serfdom in its present position is evil ... but trying to extinguish it now would be a matter of even more disastrous evil.” And why take the risk? Hadn’t victory over Napoleon proved that, however backward it might seem, the Russian system was strong enough to triumph and survive? So Russia’s rulers told themselves, as long as they could.

The Gendarme of Europe

For a while, they could continue to do so. For most of his reign, Nicholas was a successful warrior-tsar. He certainly devoted passion, time and excessive amounts of money to the Russian military. His army would grow to a million men—out of a total population of 60 to 70 million—but it would later become clear that he mistook spit and polish for real combat effectiveness.

Like Alexander, Nicholas considered championing the traditional order as an internationalist duty. During his reign Russia would become known as the “Gendarme of Europe” for his enthusiasm to help fellow monarchs stamp out the fires and embers of revolution. In 1831, his army crushed a revolt in Poland triggered by his rolling back of the Poles’ constitutional rights. Once a subject kingdom with its own parliament, Poland was reduced to the status of a mere province, under an appointed governor. When a series of revolutions erupted across Europe in 1848, even though Russia was suffering from famine caused by unusually poor harvests and a cholera epidemic, his troops would again march in the name of the status quo. Having already helped the Austrians suppress the revolt of the Free City of Krakow in 1846, Nicholas broke the 1848 Moldavian national movement and then sent his armies to join the Habsburg Empire in putting down the Hungarian revolution in 1849.

Again, the double-headed eagle looked both ways. Nicholas was at once committed to—as he saw it—saving Europe from its own ungodly and illegitimate dalliance with liberalism, as well as protecting Russia from European ideas. Aware of the advances in Western science and technology, he wanted to adopt the elements of the West that looked useful, while ignoring the social, political and legal contexts from which they sprang. Without a thriving mercantile class to generate investment capital, without free and open debate in universities and educated circles to generate ideas, and without greater social mobility to generate new cohorts of innovators and skeptics, Russia would always remain backward, desperately trying to adopt and adapt the inventions of others.

This did not matter so much while Nicholas’s armies were deployed against rioters, even when their enemies were Persians and Turks. It would matter a great deal when they found themselves fighting the British and the French—the most advanced military powers of the age—in Crimea, a war Nicholas had never wanted to fight, and which was paradoxically triggered by his desire to protect the European status quo.

Despite Western portrayals that presented him as just one more incarnation of a Russia bear eager to gobble up territories to the south and the southwest, in the main he felt he was acting to maintain stability. This was a real challenge when it came to Russia’s old rival, the Ottoman Empire. There was traditional bad blood there, not least given the Muslim Turks’ occupation of Orthodox Christian lands (and the “Second Rome,” Constantinople). Nicholas feared, though, that any serious pressure on this decaying empire risked bringing it down, causing chaos in southeastern Europe, angering Ottoman allies France and Britain and alienating ally Austria. Instead, he wanted to keep the Ottomans weak enough not to be a threat—and potentially even becoming Russian vassals—but not so weak that their fractious empire broke apart. Nicholas also needed to guarantee passage rights through the straits of the Dardanelles and the Bosphorus, as this was a crucial trade route for Russia, especially its grain exports.

The Greeks had been battling for independence since 1821, and in 1827, fearing an Ottoman collapse or a unilateral Russian intervention, the British and French joined with the Russians to force the empire to grant them at least autonomy. At Navarino, the allied fleet decisively defeated a larger but antiquated Ottoman force, but Sultan Mahmud II was still not willing to concede. He closed the Dardanelles to Russian shipping. In response, Nicholas put 100,000 men into the field and, after some hard fighting, by 1829 the Ottomans had been forced to sue for peace.

Crimea and Punishment

Ultimately, though, the “Eastern Question” was less about Turkey than European great-power politics. Britain feared Russian expansionism: both London and St. Petersburg saw fiendish long-term strategy in their rival’s clumsy short-term responses to a chaotic world. France’s newly minted emperor, Napoleon III, was looking for glory. The Ottomans feared Russia. And Nicholas not only feared being locked away from the Mediterranean, but resented what he saw as Western double standards. He found his sentiments accurately reflected in a report by a Russian scholar, Mikhail Pogodin, who wrote that “we can expect nothing from the West but blind hatred and malice.”

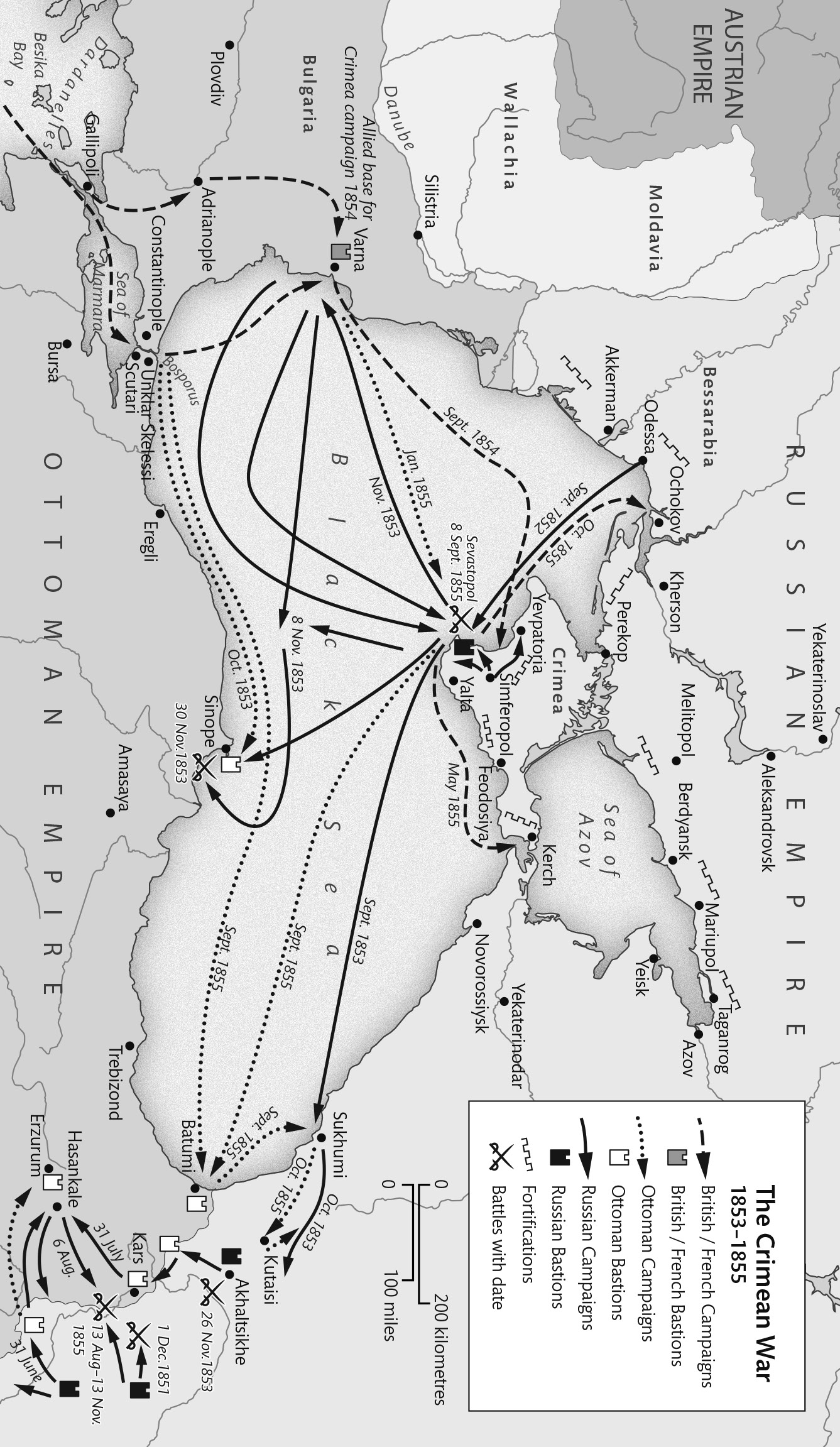

A squabble over the rights of Christians in the Ottoman-occupied Holy Land led to Nicholas asserting himself as guardian of the Orthodox community. Attempts to broker an agreement fell through, and in 1853 the Ottomans—believing they had British and French support—declared war on Russia. It started badly for them, as Russian troops crossed the Danube into Romania and Russian ships smashed a naval squadron at Sinope. Fearing an Ottoman collapse, the French and British rushed forces to the Balkans, just as the Russians pulled back.

Having stirred up jingoistic sentiment at home, neither government could afford to remain, as Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels put it, with “the French doing nothing and the British helping them as fast as possible.” So they chose instead to turn their attentions to the Crimean Peninsula and Russia’s main base on the Black Sea, Sevastopol. It took almost a year for an allied force to take the city in a war marked as much for the incompetence as the bravery shown on both sides. The infamous Charge of the Light Brigade, when miscommunication sent British cavalry straight at Russian cannon, was in many ways the epitome of both.

© Helen Stirling

Nonetheless, this war was to prove a turning point for Russia, albeit one Nicholas himself would not see through. He died in 1855, while Sevastopol was under siege, and with him, it seemed, died the comforting notion that Russia was not at risk from its backwardness. With steamships, British and French forces could be reinforced and resupplied more quickly than the Russians, even though they were fighting on their own soil, could manage on foot. The rifles the British and French infantry used could outrange antiquated smoothbore Russian cannon. The brilliance of some tsarist generals and the stoic bravery of many of their troops could not conceal the fact that Russia’s serf army was outgunned, undertrained and often badly led. It was, in every way, a metaphor for the country’s social, economic and technological circumstances.

The war would prove a catalyst for arguably the most ambitious social engineering project Russia had yet to see. The new tsar, Nicholas’s son Alexander II (r. 1855–81), quickly sued for peace, and turned his gaze inward. Russia had failed to modernize, and that failure risked leaving it vulnerable in an age of aggressive imperialism and a changing European balance of power. The serfs wanted their land, but had no answer as to what this would do to an empire that depended on its landed elites. The Westernizers wanted constitutional monarchy and industrialization, but had no answer as to what this would mean for Russia. The conservative Slavophiles clung to the notion that Russian culture needed to be purged of Western decadence, but had no answer as to how that could be reconciled with necessary modernization. Everyone agreed something had to be done—as Tolstoy put it, “Russia must either fall or be transformed”—but there was no agreement as to what. All eyes turned to Alexander.

Liberation Lite

Even before his coronation, Alexander had made it clear that he was willing to grasp the nettle Nicholas had avoided, declaring that it was “better to abolish serfdom from above than to wait until it begins to abolish itself from below.” Reform was necessary both to forestall revolution but also lest foreign powers begin to feel, as once the Poles and Swedes had, that they could meddle in Russian politics. However, that reform would have to be managed from above, both to ensure it was measured, but also because, between the political backwardness of the peasantry, the relative absence of a middle class and the self-interest of the aristocracy, who else could be trusted to do this than the tsar?

All this, though, meant that there were two fatal and irreconcilable paradoxes to Alexander’s reforms. First of all, over liberalization. Equality before the law, constitutionalism and the like inevitably posed a challenge to Alexander’s belief that strong executive power was needed to drive reform forward, because they are to a large extent explicitly about limiting the untrammeled powers of state and tsar. The politically active forces that these reforms generated and required were soon forced into a choice: serve the state and lose the capacity for independent action, or be treated as subversives. The second paradox was over execution. Alexander depended on the state bureaucracy and gentry to carry out his reforms, the very people whose interests were at threat, and he could not afford to alienate them.

Nonetheless, Alexander undoubtedly earned his epithet as the “Tsar-Liberator.” He pardoned political prisoners, relaxed censorship, restored the independence of the universities, established independent courts and presided over a major expansion of schools for the poor. The centerpiece of his “Great Reforms” was intended to reshape the country’s agrarian and social base by finally tackling serfdom. After all, 46 million of the tsar’s 60 million subjects were still serfs, and they made poor stewards of the land they did not own and indifferent soldiers for a state they did not respect. In 1861, the Emancipation Decree promised to change all that, freeing the serfs over the next two to five years, depending on their status. What they really wanted, though, was their own land, and there was the rub. Simply allowing them to take over the land they farmed would at a stroke bankrupt most of the landed gentry, so instead the serfs were forced to buy it off them, paying “Redemption Dues” over the next 49 years.

It was a classic case of a compromise that pleased no one. The serfs had for generations dreamed of the day the “little father” in St. Petersburg would finally free them, and initial enthusiasm quickly turned to anger when they realized they would have to pay—at prices they often could not afford—for the land they felt was morally theirs, earned with their blood and sweat. In 1861 alone, the army had to be called out to put down riots and protests on average more than once a day. Not that the landowners were much happier. Many had been in debt to the state, and the money they were paid for the land often simply went right back to the government. Besides, as the peasants could often not afford to keep up with their payments, even this income dried up. As if this were not enough, a major administrative reorganization that accompanied the Emancipation, with the creation of new elected local councils called zemstvos, meant that the rural gentry were also expected to do the state’s work in the regions, from collecting taxes to dispensing justice.

Meanwhile, a new class was rising. Cities were beginning to expand, and with them a merchant class. The civil service expanded with the professionalization of many functions once handled by landlords and serf owners, and so too did the universities. Between 1860 and 1900, the number of professionally trained Russians grew from 20,000 to 85,000. Still a small fraction of the population, but for the first time this intermediary layer, neither peasant nor gentry, began to form a distinct, self-conscious intelligentsia identity. Shaped by Western ideas and Russian culture, they would form the basis for a rising revolutionary movement. In every aspect of life, new ideas were beating against the walls of the old order. Artists began to challenge the formalism of the Imperial Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg, which for over a century had imposed its stultifyingly conservative standards on the cultural scene. Wealthy women and members of the St. Petersburg literary set began agitating for more access to education, over the protests of traditionalists who, as one university rector put it, “know women’s limitations better than they seem to know them themselves.” From letter writing to bomb throwing, those unhappy with the existing order felt increasingly free to express their concerns and advance their agendas.

Alexander, it seems, was genuinely surprised by the response to his reforms. Demonstrating that he was his father’s son, his instinctive response was to fall back on repression. A vicious circle saw heavy-handed policing and violent political protest feed off each other. In a triumph of urban romanticism, the Populists, a Russian take on the socialism then rising in the West, saw the peasant commune as some kind of utopian communist microstate. When they “went to the people” with this notion, the peasants they idealized tended to ignore them, drive them out or hand them over to the police. So they, and other groups, turned to terrorism instead, and with every prince or general they killed, the more the Gendarmerie and Third Section cracked down with the kind of vicious enthusiasm that drove more recruits into the revolutionaries’ arms.

Over time, though, Alexander seems to have come to realize that intelligentsia radicalism and peasant discontent were two separate phenomena, and opted to step back from repression. On the morning of 31 March 1881, he resolved to call a commission to launch a second wave of even deeper reforms, including a constitution. And with flawless timing, the Narodnaya Volya (“People’s Will”) terrorist group, which had tried and failed to kill him seven times already, finally managed to assassinate him, that very afternoon.

The Reaction

Alexander’s son and heir, Alexander III (r. 1881–94), was a narrow-minded man at the best of times and would likely have adopted a more reactionary line even had his father not just been assassinated. Under the influence of his zealot of a former tutor, Konstantin Pobedonostsev, he oppressed Russia’s minority peoples—most notably the Jews—and presided over a massive expansion of repression. Police certificates of “reliability” were needed to get into university or jobs deemed “responsible,” and appointed land commandants became virtual local overlords. His answer to the dilemmas of modernization was to tax the peasantry all the harsher to make money to buy what Russia needed from the West. As his finance minister Ivan Vyshnegradsky put it, “Let us starve, but let us export.” (Vyshnegradsky was a multimillionaire; there was little risk of his starving, but up to half a million ordinary Russians did in the 1891–2 famine.)

When Alexander died in 1894, his son succeeded him. Nicholas II (r. 1894–1917), the last Romanov, was perhaps the most ill-starred of his line. This was a time when the Russian Empire needed a tsar with the will of Peter the Great, the wit of Catherine, the cunning of Dmitry Donskoi, the reformism of Alexander II and a touch of the iron conviction of Nicholas I. It got a man who was unimaginative in his conservatism, vacillating in his convictions, meek before the strong-willed, imperious to the well-meaning. He himself felt unprepared for the position. “What is going to happen to me and all of Russia?” he asked his cousin and brother-in-law, Grand Duke Alexander, on the eve of his coronation. What, indeed?

He was that most terrible of leaders, both foolish and dutiful. It quickly became clear he had no answers to the challenges facing Russia, challenges that were ironically being magnified by successful economic development. Under Vyshnegradsky’s successor, Sergei Witte, the 1890s saw the economy grow some 5 percent annually. However, real average incomes actually fell, as this continued to be modernization on the cheap. The cities grew, with the worst slums being virtual no-go areas for the police and the new industrial workforce becoming susceptible to revolutionary ideas. People were hungry and angry, a combustible situation just waiting for a spark.

That spark would come from the Far East. Russia’s eastward expansion had brought it into conflict over Manchuria and Korea with a rising and aggressive Japan. Believing that Japan would not fight a European power, and egged on by his cousin Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany, Nicholas put little effort into reaching a deal, and was thus stunned when the Japanese launched a surprise attack on the Russian fleet at Port Arthur in 1904. Nonetheless, he seems to have believed that, in the words of Interior Minister Vyacheslav Plehve, “a nice, victorious little war” would help reunite the country.

It soon became clear that this would be anything but. Japan had, after all, been modernizing rapidly and was fighting closer to home. At land and sea they were advancing, and so desperate were the Russians to reinforce their Pacific Squadron that they had to send the Baltic Fleet the long way there. The voyage hardly started auspiciously, when they mistook the Hull herring fishing fleet for Japanese torpedo boats and opened fire. As if that were not unimpressive enough, they only managed to sink one, and a Russian cruiser was damaged in the crossfire. War with Britain was narrowly averted, but after traveling over 18,000 nautical miles (33,000 kilometers) in seven months, the Baltic Fleet was then trounced at the Battle of Tsushima in 1905, essentially ending the war.

Maybe a victory would have helped, but an expensive and humiliating defeat undoubtedly battered the regime further. The tsar still had a certain legitimacy as God’s chosen representative and the “little father” of his people. Not for long. In January 1905, more than 150,000 people staged a march to the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg to deliver a loyal petition to the tsar. They were peaceful, singing hymns and holding icons. The tsar wasn’t even there at the time, but someone panicked, shooting started, and the Imperial Guards began firing volleys into the crowd. By the time the gun smoke had cleared, hundreds of protesters and bystanders were dead. And so too, arguably, were the last remnants of the tsar’s standing with his people. This was the spark that was needed to ignite the country, to trigger the 1905 Revolution that Bolshevik leader Lenin would later call the “Great Dress Rehearsal” for the 1917 convulsions that would finally sweep tsarism away.

Further reading: Dominic Lieven’s magisterial Russia Against Napoleon (Penguin, 2009) is an essential, detailed account, a worthy historical counterpart to Leo Tolstoy’s epic (in every sense) War and Peace (there are many versions; I recommend the Anthony Briggs translation; Penguin, 2005). W. Bruce Lincoln, who writes beautifully, has the best biography of Nicholas I (Northern Illinois University Press, 1989) and an evocative portrayal of Russia at the turn of the century, In War’s Dark Shadow (Oxford University Press, 1983). Robert Service’s The Last of the Tsars: Nicholas II and the Russian Revolution (Macmillan, 2017) is a judicious biography of this deeply flawed man. The Marquis de Custine’s Empire of the Czar (Doubleday, 1989) is a contemporary account that is still very readable today.