Chapter 2

Preparing for the GED Social Studies Test

In This Chapter

Getting familiar with the Social Studies test’s topics and components

Getting familiar with the Social Studies test’s topics and components

Surveying the types of questions and passages on the test

Surveying the types of questions and passages on the test

Preparing for and writing the essay

Preparing for and writing the essay

Optimizing your performance through proper preparation

Optimizing your performance through proper preparation

Budgeting your time

Budgeting your time

The GED Social Studies test assesses your skills in understanding and interpreting concepts and principles in civics, history, geography, and economics. Consider this test as a kind of crash course in where you’ve been, where you are, and how you can continue living there. You can apply the types of skills tested on the Social Studies test to your experience in visual, academic, and workplace situations as a citizen, a consumer, or an employee.

This test includes questions drawn from a variety of written and visual passages taken from academic and workplace materials as well as from primary and secondary sources. The passages in this test are like the ones you read or see in most daily newspapers and news magazines. Reading either or both of these news sources regularly can help you become familiar with the style and vocabulary of the passages you find here.

In this chapter, we take a look at the skills required for the Social Studies section of the GED test, the format of the test, and what you can do to prepare.

Looking at the Skills the Social Studies Test Covers

The question-and-answer items of the Social Studies test evaluate several specific skills, including the ability to read and understand complex text, interpret graphs and relate graphs to text, and relate descriptive text to specific values in graphs. For example, an item may ask about the relationship between a description of unemployment in text and a graph of the unemployment rate over time.

You don’t have to study a lot of new content to pass this test. Everything you need to know is presented to you with the questions. In each case, you see some content, either a passage or a visual; a question or direction to tell you what you’re expected to do; and a series of answer options.

You don’t have to study a lot of new content to pass this test. Everything you need to know is presented to you with the questions. In each case, you see some content, either a passage or a visual; a question or direction to tell you what you’re expected to do; and a series of answer options.

The questions do require you to draw on your previous knowledge of events, ideas, terms, and situations that may be related to social studies. From a big-picture perspective, you must demonstrate the ability to

- Identify information, events, problems, and ideas and interpret their significance or impact.

- Use the information and ideas in different ways to explore their meanings or solve a problem.

- Use the information or ideas to do the following:

- Distinguish between facts and opinions.

- Summarize major events, problems, solutions, and conflicts.

- Arrive at conclusions based on source material.

- Influence other people’s attitudes.

- Find alternate meanings in a passage or mistakes in logic.

- Identify causes and their effects.

- Recognize how writers may have been influenced by the times in which they lived and a writer’s historical point of view.

- Compare and contrast differing events and people and their views.

- Compare places, opinions, and concepts.

- Determine what impact views and opinions may have both at this time and in the future.

- Organize information to show relationships.

- Analyze similarities and differences in issues or problems.

- Give examples to illustrate ideas and concepts.

- Propose and evaluate solutions.

- Make judgments about the material’s appropriateness, accuracy, and differences of opinion. Some questions will ask you to interpret the role information and ideas play in influencing current and future decision making. These questions ask you to think about issues and events that affect you every day. That fact alone is interesting and has the potential to make you a more informed citizen of the modern world. What a bonus for a test!

About one-third of the questions test your ability to read and write in a social studies context. That means you’ll be tested on the following:

- Identifying and using information from sources

- Isolating central ideas or specific information

- Determining the meaning of words or phrases used in social studies

- Recognizing points of view, differentiating between fact and opinion, and identifying properly supported ideas

Another third of the questions ask you to apply mathematical reasoning to social studies. Much of that relates to the ability to do the following:

- Interpret graphs.

- Use charts and tables as source data and interpret the content.

- Interpret information presented visually.

- Differentiate between correlation and causation. Just because one event occurred after another (correlation) doesn’t necessarily mean that the first event caused the second (causation).

The remaining third deals with applying social studies concepts. That includes the following:

- Using specific evidence to support conclusions

- Describing the connections between people, environments, and events

- Putting historical events into chronological order

- Analyzing documents to examine how ideas and events develop and interact, especially in a historical context

- Examining cause-and-effect relationships

- Identifying bias and evaluating validity of information, in both modern and historical documents

Being aware of what skills the Social Studies test covers can help you get a more accurate picture of the types of questions you’ll encounter. The next section focuses more on the specific subject materials you’ll face.

Understanding the Social Studies Test Format

You have a total of 90 minutes to complete the Social Studies test. That time is split between the two components of the test. You have 65 minutes to answer a variety of question-and-answer items and then 25 minutes to write an Extended Response (essay) of 250 to 500 words. You can’t transfer time from one section to the other. The question-and-answer section consists mostly of multiple-choice questions with a few fill-in-the-blank questions. The multiple-choice questions come in various forms. Most are the standard multiple-choice you know from your school days. Other formats include drop-down menu, drag-and-drop, and hot-spot items. For more about responding to these different question types on the computerized version of the GED test, check out GED Test For Dummies (Wiley).

In the following sections, we explore the subject areas the Social Studies test covers, give you an overview of the types of passages you can expect to see, and take a look at what the Extended Response is all about.

Checking out the subject areas on the test

The question-and-answer section of the Social Studies test includes about 50 questions. The exact number varies from test to test because the difficulty level of the questions varies. Most of the information you need will be presented in the text or graphics accompanying the questions, so you need to read and analyze the materials carefully but quickly. The questions focus on the following subject areas:

- Civics and government: About 50 percent of the Social Studies test includes such topics as rights and responsibilities in democratic governance and the forms of governance.

- American history: About 20 percent of the test covers a broad outline of the history of the United States from precolonial days to the present, including such topics as the War of Independence, the Civil War, the Great Depression, and the challenges of the 20th century.

- Economics: Economics involves about 15 percent of the test and covers two broad areas — economic theory and basic principles. That includes topics such as how various economic systems work and the role of economics in conflicts.

- Geography and the world: In broad terms, the remaining 15 percent covers the relationships between the environment and societal development; the concepts of borders, region, and place and diversity; and human migration and population issues.

The test materials cover these four subject areas through two broad themes:

- Development of modern liberties and democracy: How did the modern ideas of democracy and human and civil rights develop? What major events have shaped democratic values, and what writings and philosophies underpin American views and expressions of democracy?

- Dynamic systems: How have institutions, people, and systems responded to events, geographic realities, national policies, and economics?

The Extended Response item (that is, the essay you write at the end of the test) is based on enduring issues, which cover issues of personal freedoms in conflict with societal interests and issues of governance — states’ rights versus federal powers, checks and balances within government, and the role of government in society. These issues all require you to evaluate points of view or arguments and determine how such issues represent an enduring theme in American history. You need to be able to recognize false arguments, bias, and misleading comparisons.

If you’re a little worried about all of these subject areas, relax. You’re not expected to have detailed knowledge of all the topics listed. Although it helps if you have a general knowledge of these areas, most of the test is based on your ability to reason, interpret, and work with the information presented in each question. Knowing basic concepts such as checks and balances or representative democracy helps, but you don’t need to know a detailed history of the United States.

Identifying the types of passages on the test

The passages in the Social Studies test are taken from two types of sources:

- Academic material: The type of material you find in a school — textbooks, maps, newspapers, magazines, software, and Internet material. This type of passage also includes extracts from speeches or historical documents.

- Workplace material: The type of material found on the job — manuals, documents, business plans, advertising and marketing materials, correspondence, and so on.

The material may be from primary sources (that is, the original documents, such as the Declaration of Independence) or secondary sources — material written about an event or person, such as someone’s opinions or interpretation of original documents or historic events, sometimes long after the event takes place or the person dies.

Answering questions about text and visual materials

The source materials for the question-and-answer items facing you on the test fall into three broad categories. The materials require you to extract information, come to conclusions, and then determine the correct answer. These source materials consist of textual materials, something with which you’re probably already quite familiar; visuals, like maps and diagrams; and statistical tables. Each of these categories requires careful reading, even the visuals, because the information you need to extract can be buried anywhere.

Questions about text passages

About half of the question-and-answer portion of the Social Studies test includes textual passages followed by a series of questions based on that passage. Your job is to read the passage and then answer questions about it.

When you’re reading these passages on the test (or in any of the practice questions or tests in this book), read between the lines and look at the implications and assumptions in the passages. An implication is something you can understand from what’s written, even though it isn’t directly stated. An assumption is something you can accept as the truth, even though proof isn’t directly presented in the text.

Be sure to read each item carefully so you know exactly what it’s asking. Read the answer choices and go through the text again carefully. If the question asks for certain facts, you’ll be able to find those right in the passage. If it asks for opinions, you may find that the text directly states those opinions or simply implies them. (And they may not match your own opinions, but you still have to answer with the best choice based on the material presented.)

Be sure to read each item carefully so you know exactly what it’s asking. Read the answer choices and go through the text again carefully. If the question asks for certain facts, you’ll be able to find those right in the passage. If it asks for opinions, you may find that the text directly states those opinions or simply implies them. (And they may not match your own opinions, but you still have to answer with the best choice based on the material presented.)

If a question doesn’t specifically tell you to use additional information beyond what is presented in the passage, use only the information given. An answer may be incorrect in your opinion but if it is correct according to the passage (or vice versa), you must go with the information presented, unless you’re told otherwise. Always select the most correct answer choice, based on the information presented.

Questions about visual materials

To make sure you don’t get bored, the other half of the question-and-answer portion of the Social Studies test is based on maps, graphs, tables, political cartoons, diagrams, photographs, and artistic works. Some items combine visual material and text. You need to be prepared to deal with all of these types of items.

If you’re starting to feel overwhelmed about answering questions based on visual materials, consider the following:

-

Maps do more than show you the location of places. They also give you information, and knowing how to decode that information is essential. A map may show you where Charleston is located, but it can also show you how the land around Charleston is used, what the climate in the area is, and whether the population there is growing or declining. Start by examining the print information with the map, the legend, title, and key to the colors or symbols on the map. Then look at what the question requires you to find. Now you can find that information quickly by relating the answer choices to what the map shows.

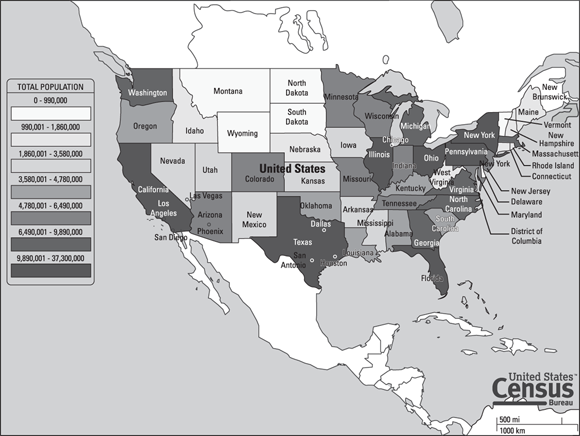

For example, the map in Figure 2-1 shows you the following information:

- The population of the United States for 2010

- The population by state by size range

Indirectly, the map also shows you much more. It allows you to compare the population of states with a quick glance. For example, you can see that Florida has a larger population than Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming together. If you were asked what the relationship is between a state’s size and population, you could argue, based on this map, that there isn’t much relationship. You could also show that the states around Lakes Erie and Ontario have a higher population density than the states in the Midwest. This kind of conclusion-drawing is part of the skill of analyzing maps.

- Every time you turn around, someone in the media is trying to make a point with a graph. The types of graphs you see in Figure 2-2 are very typical examples. The real reason people use graphs to explain themselves so often is because a graph can clearly show trends and relationships between different sets of information. The three graphs in Figure 2-2 are best suited for a particular use. For example, the bar graphs are great for comparing items over time, the line graphs show changes over time, and the pie chart shows you proportions. The next time you see a graph, such as the ones in Figure 2-2, study it. Be sure to look carefully at the scale of graphs; even visual information can fool you. A bar graph that shows a rapid rise of something may in fact show no such thing. It only looks that way because the bottom of the chart doesn’t start with values of zero. Check carefully to make sure you understand what the information in the graph is telling you. (Note: Graphs are also called charts.)

-

Tables are everywhere. If you’ve ever looked at the nutrition label on a food product, you’ve read a table. Study any table you can find, whether in a newspaper or on the back of a can of tuna. The population data table in Figure 2-3 is an example of the kinds of data you may see on the test. That table shows you a lot of information, but you can extract quite a bit more information that isn’t stated. Just a quick look at the numbers tells you that nearly 1.6 million people are enlisted in the armed forces. How do you know that? Subtract the number in the Civilian Population column from the Resident Population Plus Armed Forces Overseas column. You can also calculate the change in the overall population, the rate of increase of both the population and the armed forces personnel, and even the size of the armed forces stationed in the United States compared to serving overseas.

Just like graphs, tables are also sometimes called “charts,” which can be a little confusing. Regardless of what they’re called, you need to be prepared to extract information, even if it isn’t stated directly.

- Political cartoons appear in the newspapers every day. If you don’t read political cartoons in the daily newspaper (usually located in the Editorial or Op-Ed pages), give them a try. Some days, they’re the best entertainment in the paper. Political cartoons in the newspaper are usually based on an event in the last day or week. They can be nasty or funny and are always biased. If you want to get the most out of political cartoons, look for small details, facial expressions, and background clues. The cartoons on the test are obviously older than the ones in daily newspapers, so you may not get the context unless you’ve been reading the newspapers or watching the news for the past several weeks or months.

- You’ve no doubt seen countless photographs in your day. Photos are all around you. All you need to do to prepare for the photograph-based questions on the test is to begin getting information from the photographs you see. Start with the newspapers or magazines, where photos are chosen to provide information that connects directly to a story. See whether you can determine what message the photograph carries with it and how it relates to the story it supports.

- You probably like to look at works of art. On the Social Studies test, you have a chance to “read” works of art. You look at a work of art and gather information you can use to answer the item. To get yourself ready to gather information from works of art on the test, take a look at art galleries, the Internet, and library books. Lucky for you, some books even give some background or other explanation for these works.

It doesn’t matter whether a visual passage is a table, a cartoon, a drawing, or a graph — as long as you know how to read it. That’s what makes maps, tables, and charts such fun.

It doesn’t matter whether a visual passage is a table, a cartoon, a drawing, or a graph — as long as you know how to read it. That’s what makes maps, tables, and charts such fun.

If you’re unsure of how to read a map (or any other visual material except cartoon), go to any search engine and search for “map reading help” or a similar term to find sites that explain how to read those elements. If you try to follow the same procedure for political cartoons, you’ll get a lot of actual cartoons but not a lot of explanations about them. Instead, search using “political cartoons analysis,” which will find lots of cartoons but also some help understanding them. Afterward, look at some examples of political cartoons (either in the newspaper or online) and use your analysis skills to understand what the cartoonist is saying to you. Remember the figures in the drawings are symbolic and exaggerated to make a point. Then look up the topic of the cartoon and the date to read some of the news stories it refers to. Talk about the cartoon with your friends. If you can explain a cartoon or carry on a logical discussion about the topic, you probably understand its contents.

If you’re unsure of how to read a map (or any other visual material except cartoon), go to any search engine and search for “map reading help” or a similar term to find sites that explain how to read those elements. If you try to follow the same procedure for political cartoons, you’ll get a lot of actual cartoons but not a lot of explanations about them. Instead, search using “political cartoons analysis,” which will find lots of cartoons but also some help understanding them. Afterward, look at some examples of political cartoons (either in the newspaper or online) and use your analysis skills to understand what the cartoonist is saying to you. Remember the figures in the drawings are symbolic and exaggerated to make a point. Then look up the topic of the cartoon and the date to read some of the news stories it refers to. Talk about the cartoon with your friends. If you can explain a cartoon or carry on a logical discussion about the topic, you probably understand its contents.

All the visual items you have to review on this test are familiar. Now all you have to do is practice until your skills in reading and understanding them increase. Then you, too, can discuss the latest political cartoon or pontificate about a work of art.

Writing the Social Studies Extended Response

The Social Studies Extended Response requires you to relate materials to key issues in American economic, political, and social history. Although you don’t need a detailed knowledge of American history, you must have a broad sense of key issues because your answer needs to go beyond just the facts and attitudes presented in the text. In the following sections, we offer guidance in how to prepare for and write your Extended Response.

Gearing up for the Extended Response

For the Social Studies Extend Response item, you’re given a quotation and a passage. Your assignment is to write a 250-to-500-word essay in 25 minutes, based on your analysis of each source text. You’re asked to discuss how these materials present an enduring issue in American history and society. You must use quotes from the source documents to support your argument. You should also use your own personal knowledge to support your arguments. Read the instructions carefully. Write the key words down on your tablet to ensure you don’t misread. As you prepare your answer, go back to the basic question and make sure you’re staying on topic and that all of your answering points relate strictly to that topic.

Because the GED test is now administered on the computer, you’ll use the computer’s word processor to write your response. The word processor has all the functions you’d expect — copy, paste, undo, and redo — but it doesn’t include either a grammar-checker or a spell-checker. That’s part of your job.

The evaluation looks at three specific areas of essay writing:

- Creation of argument and use of evidence:

- Your argument must show that you understand not only the arguments being presented but also the relationship between the ideas presented and their historical or social context.

- You must effectively use relevant ideas from the source text to back your arguments.

- Development of ideas and organizational structure:

- Your arguments develop logically and clearly.

- You connect details and main ideas.

- You explain details as required to further your argument.

- Clarity and command of Standard English:

- You use proper English.

- You demonstrate a command of proper writing conventions.

- You show correct usage of subject-verb agreement, homonyms, capitalization, punctuation, and proper word order.

To prepare for the Extended Response item, we say read, read, and then read some more. Look for magazine and newspaper editorials. Look for documentaries on television, DVD, or even online about controversial issues in American history. For example, look for a documentary on school busing in the 1950s. List the issues surrounding the decision to bus pupils in one area to schools in another area. Consider the issues of personal freedom, the rights to choose, and civil liberties in a larger community sense. Look at the changing views on the role of government in our daily lives. What forces drove decision making at that time? How were those decisions a reflection of their times, and to what extent do similar views and decisions still apply today?

Writing your Extended Response: A sample prompt

Here’s a sample Extended Response prompt, like you may see on the Social Studies test.

-

Stimulus: The following statements were made about slavery sometime before the Civil War. The Jay letter, written almost a hundred years before the Civil War, reflects the views of abolitionists, common right up to the Civil War. Hammond’s speech reflects the continuing justification of, and for, slavery. In what way is this an enduring issue to this day?

It is much to be wished that slavery may be abolished. The honour of the States, as well as justice and humanity, in my opinion, loudly call upon them to emancipate these unhappy people. To contend for our own liberty, and to deny that blessing to others, involves an inconsistency not to be excused. (John Jay, letter to R. Lushington, March 15, 1786.)

In all social systems there must be a class to do the menial duties, to perform the drudgery of life. That is, a class requiring but a low order of intellect and but little skill. Its requisites are vigor, docility, fidelity. Such a class you must have, or you would not have that other class which leads progress, civilization, and refinement. It constitutes the very mud-sill of society and of political government; and you might as well attempt to build a house in the air, as to build either the one or the other, except on this mud-sill. Fortunately for the South, she found a race adapted to that purpose to her hand. A race inferior to her own, but eminently qualified in temper, in vigor, in docility, in capacity to stand the climate, to answer all her purposes. We use them for our purpose, and call them slaves. We found them slaves by the common “consent of mankind,” which, according to Cicero, “lex naturae est.” The highest proof of what is Nature’s law. (The “Mudsill Theory,” James Henry Hammond, speech to the U.S. Senate, March 4, 1858.)

Prompt: Isolate the main issue presented in these two quotes, identify the points of view of the authors, consider how these positions reflect an enduring issue in American history, and use your own knowledge of the issue to show how this continues to be one of the enduring issues.

To start drafting your response, first make a list of key points each author uses to support his position. List them as pro and con, and relate them to the enduring issue you’ve identified. Now think back to your own general knowledge of the issue and consider what other information you can bring to the essay to explain how and why this is an enduring issue. For example, you may consider why the founding fathers argued nonwhites should count as only three-fifths of a person. You may consider that there will always be people at the bottom of the food chain, regardless of race, and there will always have to be people who do the drudge work. Go beyond the idea of racial discrimination and consider the idea of equality of opportunity. Whatever points you choose to use, you need to go beyond the text and build on your own knowledge of American history and issues.

When composing your response, you should select a few key statements. In the Jay letter, the most significant statement is “To contend for our own liberty, and to deny that blessing to others, involves an inconsistency not to be excused.” How can society argue that it’s acceptable to have some deprived of freedom when regarding freedom essential for itself? The Hammond speech is more practical. In essence, he states that in order for some to be wealthy, others must be poor. Now, you have the enduring issue. You can discuss it in several ways: the dissonance between slavery and freedom, or the necessity of poverty’s existence for wealth’s existence. In modern terms, you may argue about the 99 percent and the 1 percent. That then allows you to develop an argument about the enduring issue. You need to use quotes from these two source documents to show that it’s indeed an enduring issue and add your own information to those quotations to back the argument.

Examining Preparation Strategies That Work

To improve your skills and get better results, we suggest you try the following strategies when preparing for the Social Studies test:

-

Take as many practice tests as you can get your hands on. The best way to prepare is to answer all the sample Social Studies test questions you can find. Work through the diagnostic test in Chapter 3, the full-length practice test in Chapter 13, and practice questions in the chapters in Part II of this book. Search online for additional practice questions, such as those at www.gedtestingservice.com/educators/freepracticetest. (Note: This site is intended for educators teaching the GED test prep courses. Because you’re your own educator while using this book, try it. If you’re in a prep class, check with your teacher.)

You will find a few more free practice questions at www.gedtestingservice.com/testers/sample-questions.

Consider taking a preparation class to get access to even more sample Social Studies test questions, but remember that your task is to pass the test — not to collect every question ever written.

- Practice reading a variety of documents. The documents you need to focus on include historic passages from original sources (such as the Declaration of Independence and U.S. Constitution) as well as practical information for consumers (such as voters’ guides, atlases, budget graphs, political speeches, almanacs, and tax forms). Read about the evolution of democratic forms of government. Read about climate change and migration, about food and population, and about American politics in the post-9/11 world. Read newspapers and news magazines about current issues, especially those related to civics and government, and social and economic issues.

- Summarize the passages you read in your own words. After you read these passages, write a summary of what you read. Doing so can help you identify the main points of the passages, which is an important part of succeeding on the Social Studies test. Ask yourself the following two questions when you read a passage or something more visual like a graph:

- What’s the passage about? The answer is usually in the first and last paragraphs of the passage. The rest is usually explanation. If you don’t see the answer there, you may have to look carefully through the rest of the passage.

- What’s the visual material about? Look for the answer in the title, labels, captions, and any other information that’s included.

After you get an initial grasp of the main idea, determine what to do with it. Some questions ask you to apply information you gain from one situation to another similar situation. If you know the main idea of the passage, you’ll have an easier time applying it to another situation. - Draft a series of your own test questions that draw on the information contained in the passages you read. Doing so can help you become familiar with social studies–based questions. Look in newspapers and magazines for articles that fit into the general passage types that appear on the Social Studies test. Find a good summary paragraph and develop a question that gets to the point of the summary.

- Compose answers for each of your test questions. Write down four answers to each of your test questions, only one of which is correct based on the passage. Creating your own questions and answers helps reduce your stress level by showing you how answers are related to questions. It also encourages you to read and think about material that may be on the test. Finally, it gives you some idea of where to look for answers in a passage.

- Discuss questions and answers with friends and family to make sure you’ve achieved an understanding and proper use of the material. If your friends and family understand the question, you know it’s a good one. Discussing your questions and answers with others gives you a chance to explain social studies topics and concepts, which is an important skill to have as you get ready to take this test.

- Don’t assume. Be critical of visual material and read it carefully. You want to be able to read visual material as accurately as you read text material, and doing so takes practice. Don’t assume something is true just because it looks that way in a diagram, chart, or map. Visual materials can be precise drawings with legends and scales, or they can be drawn in such a way that the information appears to be different at first glance than it really is. Manipulating the scale for graphs is one way to skew the information. Even visuals can be biased, so “read” them carefully to determine their purposes. Verify what you think you see by making sure the information looks correct and realistic. Finally, before coming to any conclusions, check the scale and legend to make sure the graph is really showing what you think it does.

- Be familiar with general graphical conventions. Maps and graphs have conventions. The top of a map is almost always north. The horizontal axis is always the x-axis, and the vertical axis (the y-axis) is dependent on the x-axis. Looking at the horizontal axis first usually makes the information clearer and easier to understand. Practice reading charts and tables in an atlas or check out government websites where information is displayed in tables, charts, and maps.

Managing Your Time for the Social Studies Test

You have a total of 65 minutes to answer about 50 question-and-answer items and then an additional 25 minutes to write your Extended Response. The exact number of questions varies from test to test, but the time remains the same. That means you have less than 90 seconds for each question-and-answer item. Answering those items that you find easy first should allow you to progress faster, leaving you a little more time per item at the end so you can come back to work on the harder ones.

The questions on the Social Studies test are based on both regular textual passages and visual materials, so when you plan your time for answering the questions, consider the amount of time you need to read both types of materials. (See the “Questions about visual materials” section earlier in this chapter for advice on how you can get more comfortable with questions based on graphs, charts, and the like.)

When you come to a prose passage, read the questions first and then skim the passage to find the answers. If this method doesn’t work, read the passage carefully, looking for the answers. This way, you take more time only when needed.

Because you have such little time to gather all the information you can from a visual material and answer questions about it, you can’t study the map, chart, or cartoon for long. You have to skim it the way you skim a paragraph. Reading the questions that relate to a particular visual first helps you figure out what you need to look for as you skim the material.

If you’re unsure of how quickly you can answer questions based on visual materials, time yourself on a few and see. If your time comes out to be more than 1.5 minutes, you need more practice.

If you’re unsure of how quickly you can answer questions based on visual materials, time yourself on a few and see. If your time comes out to be more than 1.5 minutes, you need more practice.

Realistically, you have about 20 seconds to read the question and the possible answers, 50 seconds to look for the answer, and 10 seconds to select the correct answer. Dividing your time in this way leaves you less than 20 seconds for review or for time at the end of the test to spend on difficult items. To finish the Social Studies test completely, you really have to be organized and watch the clock.

You have 25 minutes to finish your essay for the Extended Response on the Social Studies test, and in that time you have four main tasks:

- Plan

- Draft

- Edit and revise

- Rewrite

A good plan for action is to spend 4 minutes planning, 12 minutes drafting, 4 minutes editing and revising, and 5 minutes rewriting (remembering that the computer doesn’t have a spell-checker). Keep in mind that this schedule is a tight one, though, so if your keyboarding is slow, consider allowing more time for rewriting. No one but you will see anything but the final version.

A good plan for action is to spend 4 minutes planning, 12 minutes drafting, 4 minutes editing and revising, and 5 minutes rewriting (remembering that the computer doesn’t have a spell-checker). Keep in mind that this schedule is a tight one, though, so if your keyboarding is slow, consider allowing more time for rewriting. No one but you will see anything but the final version.

Getting familiar with the Social Studies test’s topics and components

Getting familiar with the Social Studies test’s topics and components Surveying the types of questions and passages on the test

Surveying the types of questions and passages on the test Preparing for and writing the essay

Preparing for and writing the essay Optimizing your performance through proper preparation

Optimizing your performance through proper preparation Budgeting your time

Budgeting your time You don’t have to study a lot of new content to pass this test. Everything you need to know is presented to you with the questions. In each case, you see some content, either a passage or a visual; a question or direction to tell you what you’re expected to do; and a series of answer options.

You don’t have to study a lot of new content to pass this test. Everything you need to know is presented to you with the questions. In each case, you see some content, either a passage or a visual; a question or direction to tell you what you’re expected to do; and a series of answer options.

If you’re unsure of how to read a map (or any other visual material except cartoon), go to any search engine and search for “map reading help” or a similar term to find sites that explain how to read those elements. If you try to follow the same procedure for political cartoons, you’ll get a lot of actual cartoons but not a lot of explanations about them. Instead, search using “political cartoons analysis,” which will find lots of cartoons but also some help understanding them. Afterward, look at some examples of political cartoons (either in the newspaper or online) and use your analysis skills to understand what the cartoonist is saying to you. Remember the figures in the drawings are symbolic and exaggerated to make a point. Then look up the topic of the cartoon and the date to read some of the news stories it refers to. Talk about the cartoon with your friends. If you can explain a cartoon or carry on a logical discussion about the topic, you probably understand its contents.

If you’re unsure of how to read a map (or any other visual material except cartoon), go to any search engine and search for “map reading help” or a similar term to find sites that explain how to read those elements. If you try to follow the same procedure for political cartoons, you’ll get a lot of actual cartoons but not a lot of explanations about them. Instead, search using “political cartoons analysis,” which will find lots of cartoons but also some help understanding them. Afterward, look at some examples of political cartoons (either in the newspaper or online) and use your analysis skills to understand what the cartoonist is saying to you. Remember the figures in the drawings are symbolic and exaggerated to make a point. Then look up the topic of the cartoon and the date to read some of the news stories it refers to. Talk about the cartoon with your friends. If you can explain a cartoon or carry on a logical discussion about the topic, you probably understand its contents.