Chapter Nine

“All I want to hear are booms from the Burma jungle”

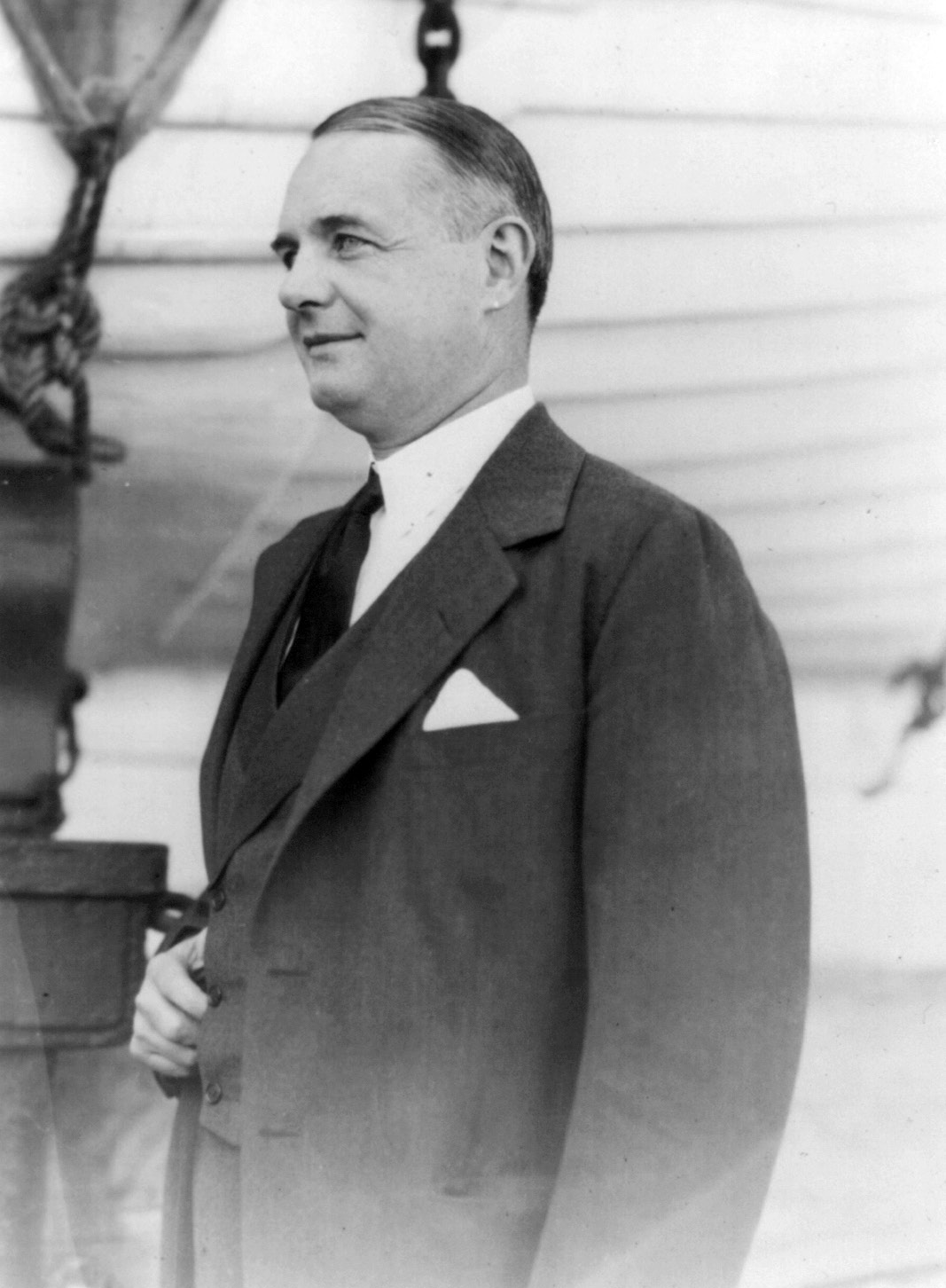

“Vinegar Joe” Stilwell

The singular experience of World War I reinforced the conception among army officers that any future conflicts would be fought with large, conventional standing armies. Thus, when the United States entered World War II the military simply lacked any kind of doctrine to wage unconventional warfare. Prior to the war military innovators looked to incorporate technological developments including airpower, communications, and mobile armored fighting vehicles as the army’s doctrine focused on large units. The very idea of guerrilla warfare and unconventional operations tended to offend commanders; many of them considered unconventional warfare uncivil, devious, and even illegal. However, the reality of the Second World War mandated tactical diversification. Commanders began to realize that in the face of limited resources and with vast tracts of land under enemy occupation, the training and supplying of local resistance fighters could be a real force multiplier. With trial and error, the mission of guerrilla warfare would eventually be handled by a semi-autonomous agency known as the Office of Strategic Services (OSS).1

By 1941, as the Axis Powers continued to threaten American interests, the void in the regular army’s unconventional warfare doctrine came to the notice of the ever-pragmatic President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Roosevelt was convinced to act on this weakness by a World War I hero and Medal of Honor winner, William J. Donovan. Since the war “Wild Bill,” as he was known, had risen as a Wall Street corporate lawyer; he was also a personal friend of FDR. Donovan had traveled overseas and observed the formation of special operations units by the British and convinced the president that the United States needed to develop similar wartime capacities. Like so many of FDR’s New Deal programs, the idea of a department that handled unconventional warfare would have several incarnations and acronyms—beginning in July 1941 when FDR named Donovan to form the Office of the Coordinator of Information (COI). In June 1942 this office would be renamed the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), and although never assigned to any branch of the military, it was staffed primarily with army personnel. It would eventually serve under the Joint Chiefs of Staff, with Donovan rising to the rank of major general by war’s end. However, the OSS would find itself caught between the rival services of the army, navy, and civilian FBI in its mission of waging unconventional warfare and gathering intelligence. (The unit was disbanded after the war, but its core need remained; it was replaced by the CIA in 1947.)2

William Joseph Donovan. Dating to July 1929, this photograph far predates Donovan’s career as the “father of American intelligence”; however, at this juncture he had already been awarded the Medal of Honor for service in France during World War I, and served as U.S. Attorney for the Western District of New York. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress

Motivated, energetic, and driven, Donovan envisioned the mission of the unit to include intelligence gathering, black propaganda (or psychological operations, “PSYOPS”), support and aid to resistance groups in occupied areas, and the use of specially trained commando units—based on the British model—that could take the lead in training guerrillas in intelligence gathering, subversion, and sabotage. By May 1943 Donovan had separated the duties of the unit into several branches, with guerrilla warfare falling under the Operational Group Command (OG). Prior to the United States entering the war he had observed the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) in Europe and as early as October 1941 had called for the creation of a separate “guerrilla corps, independent and separate from the Army and Navy.” Many officers in the army refused to accept his ideas; in fact, internal resistance was so great that the U.S. army deputy chief of staff for intelligence (or G-2), General George V. Strong, deemed Donovan’s proposals to be “essentially unsound and unproductive.” Unconventional warfare missions, Strong believed, should be carried out by regular forces. Thus, he argued, “to squander time, men, equipment and tonnage on special guerrilla organizations and at the same time to complicate the command and supply systems of the Army by such projects would be culpable mismanagement.” Despite FDR’s endorsement, Donovan’s ideas enjoyed little support from the service branches themselves. Later, when the OSS became an independent command under the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the president would convince the armed services to grant the OSS a meager allotment of support.3

When the United States entered the conflict, the Allies were focused on the war in Europe and the Mediterranean. Given these areas’ broad plains and well-developed road networks, it was clear that the outcome of the war would depend on conventional forces. However, with so much land under Axis occupation, Great Britain took the lead in establishing special operations forces to support local resistance movements. Prime Minister Winston Churchill strongly supported the concept of British special operations across the globe: The British established their own commando units in Europe and North Africa and created the Chindits (a mixed force of British and Burmese troops) in the China-Burma-India Theater (CBI).4

In North Africa, American guerrillas in the OSS had some success organizing tribes into resistance movements, and by the time Allied forces had advanced up the Italian peninsula, OSS operatives were able to organize anti-German partisans. In the summer and fall of 1944, as Germans retreated to the Gothic Line, American OSS units dropped in and brought supplies and support to the growing Italian anti-Nazi guerrilla movement. In the winter of 1944–1945, as the weather prohibited resupply of the guerrillas, the Germans were able to drive them back into the mountains. However, by the spring of 1945 the movement once again went on the offensive, and the OSS was successful in organizing seventy-five teams to train and equip partisan guerrillas. In the final drive to take Italy, the guerrillas and their American advisors blocked key roadways and harassed German troop concentrations. In the end they were responsible for killing or wounding three thousand Axis troops and capturing as many as 81,000 others, in addition to preserving key transportation hubs including Modena, Venice, Milan, and Genoa.5

From the beginning American support for partisan operations in occupied France took a backseat to the well-developed operations of the British Special Operations Executive. American forces were far too concerned with the development of regular forces and plans for the cross-Channel landing known as Operation Overlord. While the army did train Ranger units for special operations during the beach landings, the semi-autonomous OSS worked with the British to support the French Resistance. The overall invasion commander, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, did recognize the value of guerrilla forces, stating in a March 22, 1944, secret memo, “We are going to need very badly the support of the Resistance groups in France.” During and after the landing, the partisans would be organized and equipped to block or stop German reinforcements from reaching the beaches, break up rail lines, cut lines of communication, and generally disrupt German efforts. Americans worked in three-man teams with French and British operatives to form Jedburgh teams, named after partisans who had risen up in the Jedburgh region of Scotland in the twelfth century. The men parachuted into many areas of occupied Europe, contacting local resistance groups and providing support in the form of communications with the Allies, training, supply and support for resistance forces, and even raid leadership. American guerrillas were volunteers from across the army who could speak French, were in top physical condition, and had excellent skills in communications. Volunteers were trained in England and Scotland in commando fighting skills, including hand-to-hand fighting techniques. Graduates went on to the No. 1 Parachute Training School at RAF Ringway. In order to not alert the Germans, the teams did not jump into France until D-Day. Of course, the French Resistance—known as the Maquis—had been well organized and operational for years. What it needed most from the British and the Americans was logistical support. The Resistance had its greatest success in rural areas, forests, and mountains where members could launch raids and slip away undercover. From the D-Day landings in June through September 1944, 276 Jedburgh members jumped into occupied areas of Europe. In addition, twenty-two OSS operational groups (OGs) consisting of around 355 mostly French-speaking U.S. troops were inserted. The Jedburgh units and OGs supported and organized Resistance fighters as they provided intelligence, guided Allied forces, rescued downed airmen, and ambushed German forces. But the teams faced multiple problems. One of the largest was in the composition of the Maquis. Many were loyal to the forces of Charles de Gaulle, while others were openly Marxist bands with a different agenda for postwar Europe. Many American guerrillas complained that they simply had been inserted into Europe far too late and could have been far more productive had they been dropped in well prior to D-Day. By the time most of them arrived, Allied troops were only days away. Ultimately the efforts of the French Maquis and the British Special Forces, which had been organizing a guerrilla network since 1940, were far more crucial to supporting the Allies than the late arrival of the Americans. The improvised operations did, however, give the Americans an idea of how guerrilla operations might be conducted in the future.6

For commanders the best opportunity to utilize guerrilla and unconventional warfare measures is when the enemy occupies a territory that allied forces do not have the resources to occupy and hold. The China-Burma-India Theater (CBI) in World War II provides a prime example of where American guerrillas operating under the OSS’s Detachment 101 became one of the best special operations missions of the war. After sending agents to the area, General Donovan met with the infamously cantankerous commander Lieutenant General Joseph “Vinegar Joe” W. Stilwell about establishing OSS operations. At first Stilwell evaded responding to the idea, but in the absence of a direct “no” Donovan assumed he had permission to do so. Americans’ first concern was opening air and land communications with China’s Nationalist forces under Chiang Kai-shek. To supply the Chinese, Allied forces needed to control northern Burma and maintain the Burma Road to China. With limited resources, OSS officers working behind enemy lines would fill the vacuum. The terrain of Burma was ideal for light unconventional units. Rugged mountain ranges and steep valleys choked with jungles halted regular forces that could only move with the support of modern rail lines, roads, and airfields. The limited transportation routes that existed were ideal targets for irregular guerrilla forces.7

Lt. Gen. Joseph W. Stilwell inspecting Chinese troops in India. The infamous “Vinegar Joe,” on duty in 1942 in the China-Burma-India (CBI) Theater. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress

American guerrillas of Detachment 101 were organized and trained in the United States and Canada. Their first commander was Captain Carl W. Eifler, who submitted a brief plan to insert troops behind Japanese lines to begin sabotage operations. Knowing full well that it is far easier at times to beg for forgiveness than to ask for permission to act, Eifler found it necessary to quickly assemble the unit before Stilwell became fully aware of his intentions. The 250-pound Eifler, whose whisper was considered a loud roar, was ideally suited for the job. He actively used friends to recruit healthy intelligent volunteers who were experts in Asiatic cultures, medicine, demolitions, and communications. Among them would be First Lieutenant William R. “Ray” Peers, who would later command the unit. Peers first met Eifler at OSS headquarters in Washington, where according to a witness, upon introduction, Eifler “took a stiletto type dagger and drove it a good two to three inches into the top of his desk.” Peers may have been a bit shocked and wondered what he was getting into, while Eifler “looked pleased.” The volunteers went to an SOE school in Canada and an OSS camp in Maryland, where they were trained in British hand-to-hand fighting skills, demolitions, communications, and the use of Allied and enemy weapons. They also studied everything they could about Asian culture.8

Carl W. Eifler. Eifler, the first commander of Detachment 101 in the CBI Theater, was the first officer to propose contact and cooperation with Kachin natives in Burma (present-day Myanmar). Eifler was eventually able to overcome Vinegar Joe’s reluctance to engage in unconventional warfare. U.S. Army

But when Detachment 101 arrived in the CBI Theater, they found that Vinegar Joe had little use for them. He considered unconventional guerrilla warfare “illegal action,” little more than “shadow boxing.” The navy already had a plan in place to train Chinese guerrillas, and they felt the presence of the detachment undermined them. Upon arriving at Stilwell’s headquarters in July, Eifler was informed by the gruff commander, “I didn’t send for you and I don’t want you.” But in time he relented. The theater was at the bottom of the list of American priorities, and Stilwell was in desperate need of resources in Japanese-occupied Burma. The Japanese had cut the only overland road to China, and Americans were attempting to complete a new route from the India-Burma border at Ledo. Japan controlled the key town of Myitkyina and harassed American flights to China from a nearby airstrip. Stilwell approved sending Detachment 101 in to at least take the airfield, telling Eifler, “all I want to hear are booms from the Burma jungle.” As W. R. Peers recorded, Stilwell’s orders were to “establish a base camp in northeast India and from there plan and conduct operations against the roads and railroad leading into Myitkyina in order to deny the Japanese the use of the Myitkyina airfield. Establish liaison with the British authorities to effect coordination with their operations.”9

With little logistical support and insufficient intelligence to complete the mission, Eifler looked to Allied forces for support. Realizing that American servicemen could hardly go unnoticed behind the lines, he turned to the British-led Burmese army for help. They spent the remainder of 1942 in the Assam Province of northeast India, recruiting and training around fifty Burmese volunteers in jungle survival, hand-to-hand combat, weapons, demolitions, communications, and raiding and ambushing. The Americans took advantage of the knowledge that the English-speaking Burmese volunteers conveyed as well. They learned all they could about local culture, dress, and traditions. With many of their supplies destroyed by a Japanese bombing raid on their warehouse, they were nevertheless able to improvise and gather the parts necessary to build their own 500-mile-range portable radio set.10

In early 1943 Eifler proposed that Detachment 101 agents parachute behind enemy lines to make contact with friendly Kachin natives. The first raids in Burma resulted in the destruction of a railroad bridge, but were mostly ineffectual. In fact, several disasters occurred wherein American and Allied guerrillas were captured and executed by the Japanese or killed by unfriendly villagers. The chief problem was that teams were deployed too soon and with too little support, training, and, most importantly, local intelligence. As Peers recalled, “Some of them were failures; but they taught us many lessons as to what could be done and, even more important, what should not be done.” The key was to first insert local Kachins to reconnoiter the area and find out if it was safe to insert an entire team. By the end of the year they had established six small camps in northern Burma and were training the Kachin natives. They began conducting small-scale sabotage and ambushes and became very adept in collecting intelligence on the Japanese through what Peers called the “bamboo grapevine.” They also began training Kachins as guerrillas and providing teams with the weapons and support needed to attack the Japanese. The Kachins, in turn, relayed targets to the 10th Air Force and rescued downed Allied airmen. Detachment members also recruited some Kachin volunteers for advanced training and smuggled them back to bases in India for three to five months’ training in intelligence and radio communications. Some were returned to the bases while others were dropped behind enemy lines for independent operations.11

As the Allies advanced in Burma, detachment teams infiltrated Japanese lines in advance. Advance agents jumped between one hundred and two hundred miles behind enemy lines. Once in place they carefully measured the temperament of local villagers to find friendly natives. Once contact was made, teams including Americans went in to organize, equip, and train new guerrilla units in attacking the Japanese rear. This process was repeated and expanded throughout the campaign.12

Many of the Kachin people had tired of Japanese occupation and had begun retaliating against the occupiers prior to receiving American help. Once team members from Detachment 101 arrived, Kachins eagerly accepted support and became essential allies in the war. In April 1942 Second Lieutenant Vincent Curl’s group in the Hukawng Valley was befriended by Kachin leader Zhing Htaw Naw. Detachment 101 provided support including supplies, gear, and technical expertise, while Zhing Htaw Naw provided combat leadership, intelligence, and air targets and rescued downed airmen. His forces went so far as to construct an improvised airstrip that they camouflaged when not needed by placing portable huts on it. By early 1944 Curl’s forces had organized almost six hundred guerrillas.13

The Kachins were adept guerrilla warriors. Detachment 101 teams were impressed by the discipline and attention Kachin fighters exhibited when planning and preparing an ambush. When setting up the site, they took care to place their automatic weapons where they would cover the trail. In addition, they placed pungyi sticks in the dense undergrowth on each side of the trail, carefully camouflaging the site. When the ambush was sprung, the terrified Japanese would dive for cover in the brush, only to be impaled on the sticks. Once the ambush was executed, however, Americans were surprised at how quickly the Kachins would break off contact with the enemy in order to avoid casualties. As Americans learned, the Kachins’ traditional method of war was to inflict as many casualties on their enemies as practical while minimizing their own losses. Many Americans enjoyed living and working with the Kachins. While they found the local food inedible and could not understand the Kachin custom of collecting the ears of their slain, their respect for the culture grew. Americans took part in local ceremonies, including games and holiday celebrations. Kachins were also known for their trustworthiness and bravery. Once, when a supply payroll airdrop of 500,000 rupees split open, Kachin natives found and collected all of it save for a mere 300 rupees.14

By the winter of 1943–1944, Stilwell had come to see the advantage of using unconventional warfare in the theater. Now planning a campaign down the Hukawng Valley to attack the town and airfield at Myitkyina, he wanted to use the guerrillas of Detachment 101 to augment Merrill’s Marauders and Chinese forces—collectively known as the Galahad force—in the attack. Commanded by Frank Merrill, the Marauders, as the press had dubbed them, were a special light infantry unit trained to operate independently behind enemy lines. The unit operated with limited air cover and without artillery or tank support, traveling on foot with pack mules. Without heavy weapons, the unit needed to use the elements of speed and surprise to be successful—a concept that became lost on the command. Stilwell authorized Detachment 101 to expand to around three thousand fighters and promised even more support if the campaign was successful. As Galahad moved out, Detachment 101 guerrillas screened the advance and flanks of the forces and provided intelligence. On May 17, as they approached one of their primary objectives—the airfield at Myitkyina—one of the tribesmen who was to act as guide was bitten by a venomous snake, but because he was the only one who knew the back trails he refused to quit. He was so weak he had to ride horseback, but still insisted on guiding the force—allowing the Marauders to completely surprise the Japanese garrison and take the airfield. Their next objective, the town of Myitkyina itself, would not fall so easily. Originally, Detachment 101 guerrillas reported that the Japanese had around three hundred men there. However, when two Chinese units assaulted the town, they mistakenly engaged in a firefight with each other and had to pull back. Two days later, when the full force attacked, they found the Japanese had greatly reinforced the town and were able to hold off the attackers. Now ordered to lay siege, the force lacked the supplies and heavy weapons necessary for heavy operations, a blunder that needlessly cost many lives. The siege lasted past June and into the monsoon season. The campaign decimated the members of Galahad, especially the poorly supplied light forces of Merrill’s Marauders. They were already suffering terribly from disease and were nearing starvation, being dependent on limited airdrops. After suffering a second heart attack, Frank Merrill himself had to be evacuated. With little combat air support and lacking the artillery and armored vehicles necessary to fight as conventional infantry, the Galahad force struggled to capture the town. Some in the Galahad headquarters blamed Detachment 101 for inaccurate original intelligence reports, but captured Japanese prisoners confirmed that the town had about 275 defenders when the force first attacked. However, the Marauders were grateful for the support of the guerrillas. They guided patrols, screened forces, cut off Japanese lines of communication, and provided essential intelligence. Kachins even supplied elephants to haul supplies! All the while, the guerrilla force continued to expand. By August 1944, when Myitkyina finally fell, the force had close to ten thousand fighters and was conducting missions almost four hundred miles away. During the rest of the campaign the detachment’s forces continued to grow and screen Allied activities. Teams conducted over one hundred missions utilizing 350 detachment personnel and continued to conduct mop-up operations until deactivated in July 1945.15

The Kachin guerrillas of Detachment 101 became a valuable force multiplier in the China-Burma-India Theater. Consisting of only 0.8 percent of the Allied forces in the theater, the guerrillas may have been responsible for as many as 29 percent of the enemy casualties in the campaign. Commanders including Stilwell eventually realized that Allied forces could successfully utilize native forces like the Kachins in many capacities. They acted as scouts, provided intelligence, and rescued around four hundred downed airmen. The jungle canopy was too dense for aerial reconnaissance, and the unit supplied the 10th Air Force with as much as 95 percent of its targets and most of its battle damage assessment as well. In short, the Kachins, supported by Detachment 101 teams, became exceptional guerrilla fighters and rendered the Japanese occupation of Burma untenable. As in Europe, the OSS expanded throughout the area. By the end of the war the OSS was attempting to organize and train anti-Japanese forces in China and Southeast Asia. In fact, OSS officers had begun to train Viet Minh guerrillas, including Ho Chi Minh and Vo Nguyen Giap. But OSS-trained guerrillas in China, Thailand, and what would become Vietnam were just getting organized as the conflict came to an end.16