Bottles: History and Origin

Glass bottles are not as new as some people believe. In fact, the glass bottle has been around for about 3,000 years. During the 2nd century B.C., Roman glass was free-blown with metal blowpipes and shaped with tongs that were used to change the shape of the bottle or vessel. The finished item was then decorated with enameling and engraving. The Romans even get credit for originating what we think of today as the basic “store bottle” and early merchandising techniques.

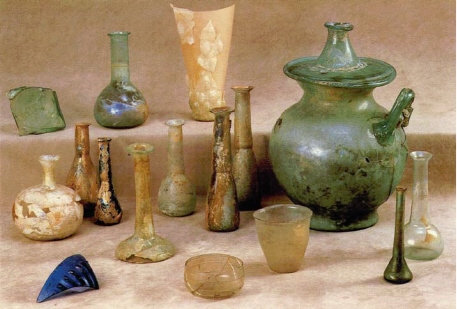

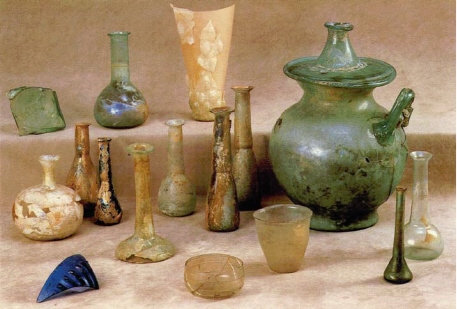

In the late 1st century B.C., the Romans began making glass vials that local doctors and pharmacists used to dispense pills, healing powders, and miscellaneous potions. The vials were 3 to 4 inches long and very narrow. The majority of early bottles made after Roman times were sealed with a cork or a glass stopper, whereas the Romans used a small stone rolled in tar as their stopper. The finished vials contained many impurities such as sand particles and bubbles because of the crude manufacturing process. The thickness of the glass and the crude finish, however, made Roman glass very resilient compared to the glass of later times, which accounts for the survival and good preservation of some Roman bottles, which have been dated as old as 2,500 years.

Roman bottles, jars, and glass objects, 1st-3rd century A.D., found in the baths and necropolises of Cimiez Nice, France.

The first attempt to manufacture glass in America is thought to have taken place at the Jamestown settlement in Virginia around 1608. It is interesting to note that the majority of glass produced at the Jamestown settlement was earmarked for shipment back to England (due to its lack of resources) and not for the new settlements. As it turned out, the Jamestown glasshouse enterprise ended up a failure almost before it got started. The poor quality of glass produced and the small quantity simply couldn’t support England’s needs.

The first successful American glasshouse was opened in 1739 in New Jersey by Caspar Wistar, a brass button manufacturer who emigrated from Germany to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1717. During a trip in Salem County, New Jersey, Wistar noticed the abundance of white sand and the proximity of clay, wood, and water transportation. He soon bought 2,000 acres of the heavily wooded land and made arrangements for experienced glass workers to come from Europe, and the factory was completed in the fall of 1739. Since English law prohibited the colonists from manufacturing anything in competition with England, Wistar kept a low profi le. In fact, most of what was written during the factory’s operation implied that it was less than successful. Caspar Wistar died in 1752 a very wealthy man and left the factory to his son Richard.

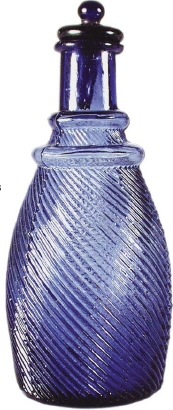

Henry Stiegel started the next major glasshouse operation in the Manheim, Pennsylvania, area between 1763 and 1774, and eventually established several more. The Pitkin Glass Works was opened in East Hartford, Connecticut, around 1783 and was the first American glasshouse to provide figured flask and also the most successful of its time until it closed around 1830 due to the high cost of wood for fuel.

To understand the successes and far more numerous failures of early glasshouses, it is essential that the reader get an overview of the challenges that glass workers faced in acquiring raw materials and constructing the glasshouse. The glass factory of the nineteenth century was usually built near an abundant source of sand and wood or coal, and near numerous roads, rivers, and other waterways for transportation of raw materials and finished products to the major Eastern markets of Boston, New York, and Philadelphia. Finding a suitable location was usually not a problem but once production was underway resources quickly diminished. The next major challenge was constructing the glasshouse building, which was usually a large wooden structure that housed a primitive furnace and was about nine feet in diameter and shaped like a beehive.

A major financial drain on the glass companies (and one of the causes of so many of the businesses failing) was the expense of the large melting pots, which held the molten glass inside the furnace. Each pot, which cost about a hundred dollars and took eight months to make, was formed by hand from a long coil of clay and was the only substance known that would not melt when the glass was heated to 2,700 degrees F. The pot’s lifespan was only about eight weeks, as exposure to high temperature over a long time caused the clay itself to turn into glass. The cost of regularly replacing melting pots proved to be the downfall of many early glass factories.

Throughout the 19th century, glasshouses continued to open and close because of changes in demand and technological improvements. Between 1840 and 1890, an enormous demand for glass containers developed to satisfy the whiskey, beer, medicine, and food packing industries. Largely because of the steady demand, glass manufacturing in the United States finally grew into a stable industry. This demand was due in large part to the settling of the western United States and the great gold and silver strikes between 1850 and 1900.

While the eastern glasshouses had been in production since 1739, the West didn’t begin its entry into glass manufacturing until 1858, when Baker & Cutting started the first glasshouse in San Francisco, California. Until then, the West had to depend on glass bottles from the eastern glasshouses. The glass manufactured by Baker & Cutting, however, was considered to be poor quality, and production was eventually discontinued. In 1862, Carlton Newman and Patrick Brennan founded Pacific Glass Works in San Francisco, California. In 1876, San Francisco Glass Works bought Pacific Glass Works and renamed the company San Francisco and Pacifi c Glass Works (SFPGW). Today, these early bottles manufactured in San Francisco are the most desired by Western collectors.

Unlike other industries of the time that saw major changes in manufacturing processes, the process for producing the glass bottles remained the same. It was a process that gave each bottle a special character, producing unique shapes, imperfections, irregularities, and various colors until 1900.

At the turn of the century, Michael J. Owens invented the first fully automated bottle-making machine. Although many fine bottles were manufactured between 1900 and 1930, Owens’ invention ended an era of unique bottle design that no machine process could ever duplicate.