2

Changing European Families

Trude Lappegård

Introduction

The most dramatic change in families is the disconnection between marriage and childbearing. Family formation has traditionally been related to a certain sequence of events including marriage as the main context for childbearing, while now, more children are born within cohabitation. Over the last four decades, men and women have delayed becoming parents and are having fewer children. The transformation of the family also includes new family arrangements such as cohabiting unions, same-sex marriages, single-parent families, and living alone. This chapter will examine the main features of these changes across Europe and discuss differences and similarities across nations in light of gender equality and developments in public policy.

Becoming a Family

Nowadays, most young people start their first union in cohabitation, but there are great variations across Europe. In just a few decades, cohabitation has gone from being a marginal phenomenon to a more accepted way of coresiding. In the recent past, childbearing has been closely linked to marriage, and the increase in childbearing in cohabitation is one of the most remarkable demographic changes to have occurred in Europe. The meanings of family and marriage have changed over time, and even though marriage rates are decreasing, most couples seem to end up married, especially when they become parents.

Cohabitation

Cohabitation has become a generally accepted living arrangement across Europe (Liefbroer and Fokkema, 2008). In most countries, very few young couples move directly into marriage, and in many countries, the majority of first unions are now within cohabitation (Sobotka and Toulemon, 2008; Billari and Liefbroer, 2010). However, the degree of cohabitation and the degree of acceptance of couples living together without planning to marry differ between countries. There are also differences in the length of time couples cohabit, if they have marriage plans and if children are born within cohabitation. Consequently, the character and meaning of cohabitation vary between individuals, countries, and over time.

The increase in cohabitation is identified as perhaps the most important of the new family behaviors described in the second demographic transition (Lesthaeghe, 1995). Ideational change and shifts toward individualism and secularism (Bumpass, 1990; Lesthaeghe, 1995; Surkyn and Lesthaeghe, 2004) are often used to explain changing lifestyle choices. It can also be attributed to factors such as increasing female economic empowerment and the contraceptive revolution (Kiernan, 2004). In addition, cohabitation may symbolize “the avoidance of the notion of dependency that is typically implicit in the marriage contract” (Kiernan, 2004, p. 52). This might be more so for women than for men. Finally, young people’s expectations toward partnerships and marriage are changing, and it is claimed that relationships have moved away from the realm of normative control and institutional regulation giving rise to the new idea of reflexive “pure relationships” based on love and mutual attraction (Giddens, 1992).

Cohabitation as we observe nowadays is new, but unmarried coresiding partnerships are not a new phenomenon. Historical sources suggest that couples across Europe cohabited for various reasons, for example, cohabitation after a marriage breakdown and in between marriages (Kiernan, 2004). For instance, in Sweden, Trost (1978) identified two types of cohabitation from the eighteenth century. One practiced by a group of intellectuals opposed to church marriage was known as a “marriage of conscience.” The other practiced among poor people who could not afford to marry was known as a “Stockholm marriage.” While the first group was a highly marginal phenomenon, the “Stockholm marriage” was the most common group of cohabitation reported from several countries (Noack, 2010).

Various classifications have been developed over the years to understand the meaning of cohabitation. The aim has been to improve knowledge about its development over time, across nations, and between individuals. One basic and often identified distinction is made between cohabitation as a stage in the marriage process and cohabitation as an alternative to marriage. First, cohabitation as a stage in the marriage process means that sharing a household is viewed as a preface to moving into a seriously committed relationship. In this way, unmarried cohabitation becomes an experiment in committing to a long-term relationship (Seltzer, 2000). One advantage of sharing a household for young couples is that they can pool resources and benefit from the economies and convenience of sharing a household (Seltzer, 2000; Smock, 2000; Perelli-Harris et al., 2010). Second, cohabitation as an alternative to marriage means that cohabitation lasts longer and has become a socially accepted way of living, both as a living arrangement for young people and also as a family form in which to have and raise children (Smock, 2000). Countries are developing along different trajectories. There is great variation in the prevalence of cohabitation, and cohabiting couples express different perceptions of the prospects for their cohabitation, that is, there is great variation in the proportion of cohabitating unions that do or do not have plans for marriage. To describe trends over time, Sobotka and Toulemon (2008) suggest three main stages that are widely shared across countries. In the first stage, which is described as diffusion, an increasing proportion of young adults enter a consensual union at the beginning of a partnership, and this eventually becomes a majority practice. In the second stage, described as permanency, cohabitation lasts longer and is less frequently converted into marriage. In the last stage, cohabitation as a family arrangement, pregnancy gradually ceases to be a strong “determinant” of marriage among cohabiting couples, and as a result, childbearing among cohabiting couples becomes common.

Using data from the 2008 European Social Survey, Noack, Berhardt, and Wiik (2013) distinguish between three cohabitation patterns. One cluster of countries (Greece, Romania, Croatia, Slovenia, Bulgaria, and Poland) represents a “traditional” pattern of living arrangements in which cohabitation is relatively rare, that is, 5% or less of the total population cohabit and 11% of those unmarried are cohabiting. At the other end of the scale, the Nordic countries, primarily Norway and Sweden, and France are clustered into “high-prevalence countries” where 20% or more of the total population are cohabiting and 34% or more of those unmarried live in cohabitation. The countries that represent a “middle group” of level of cohabitation include the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Germany, Switzerland, Hungary, Portugal, Spain, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia. In these countries, between 6% and 14% of the total population cohabit, and between 13 and 22 of those unmarried are cohabiting (Noack, Berhardt, and Wiik, 2013).

Despite these variations across countries, there is generally a relatively high acceptance of cohabitation across Europe. According to Noack, Berhardt, and Wiik (2013), in most countries, more than half of the population in the age range 15–55 does not disapprove of couples living together without being married. The highest acceptance was found in the Nordic countries and particularly Denmark where as many as 96% of the population agreed that cohabitation is completely acceptable.

Although unmarried cohabitation reaches a stage at which it becomes an alternative to marriage, substantial differences between the two partnership arrangements remain. First and foremost, men and women report a different quality of relationship in cohabitation and marriage. That is, comparative studies of European countries suggest that cohabitants have a lower level of general life satisfaction and happiness compared with married couples (Soons and Kalmijn, 2009), and cohabitants live in relationships of less commitment (more breakup plans) and less partnership satisfaction than married couples (Wiik, Keizer, and Lappegård, 2012). Importantly, in both studies, the “cohabitation gap” was narrower in countries where cohabitation is most widespread and institutionalized than in countries where cohabitation was a marginal phenomenon. This suggests that cohabitation has become “marriage-like” in relationship quality in countries where cohabitation is considered more as an alternative to marriage.

Evidence of lower relationship quality in unmarried cohabitation (Soons and Kalmijn, 2009; Wiik, Keizer, and Lappegård, 2012) including in countries where cohabitation is more widespread, and the high likelihood of cohabiting relationships dissolving (Liefbroer and Dourleijn, 2006), including those in which children are born (Andersson, 2002, 2003), can be related to cohabitation and marriage being qualitatively different unions. That is, there may be more selection into marriage because cohabiting couples who are more satisfied with their relationship are more likely to marry and those less satisfied more likely to remain cohabiting or break up.

Regulations and rights around cohabitation differ significantly. In many countries, cohabiting couples cannot access many of the normative and legal benefits that married individuals enjoy. The registration of fathers is not compulsory in some countries, and unmarried couples must negotiate bureaucratic obstacles to gain joint custody (Perelli-Harris and Sánchez Gassen, 2012). In some countries, for example, Germany, the tax code favors married couples, while in countries where cohabitants and married couples have the same rights and obligations in relation to social security, pensions, and taxations, for example, Norway, there are still differences in private law (Noack, 2010).

The transition to marriage

Marriage has undergone a remarkable transformation in its character and meaning (Sobotka and Toulemon, 2008). Even though there is an almost universal ongoing decline in marriage rates across Europe, marriage still seems to be a desirable living arrangement. However, the reasons for marriage may have changed, and the transition into marriage occurs at different stages in people’s lives than it has in the past. Available Eurostat statistics show that the mean age at first marriage in the middle of the 1970s was 22–24 years. At that time, Sweden was the forerunner, where postponement had already started and had reached a mean age of 25. By the new millennium, the mean age at women’s first marriage had increased rapidly and was found mostly in the later twenties. Setting age 30 as a threshold, only Sweden had reached this level by 2000, while 10 years later in 2010, the mean age for first-time brides was 30 years or older in the Nordic countries, France, Germany, Ireland, Luxemburg, the United Kingdom, Spain, and Italy. In Sweden, it has now reached age 33. Even though marriage ages across Europe have increased, the mean age at first marriage remains widely differentiated, especially along the “East–West divide” with lower mean ages in Eastern European countries (Sobotka and Toulemon, 2008).

The marriage decline has been one of the main markers of the second demographic transition, which is seen as being driven by changes in values (Surkyn and Lesthaeghe, 2004). The decline in marriage rates or the number of marriages per 1000 population can be seen in Table 2.1. In 1970, the marriage rates were between 7.0 and 9.0 across most of Europe. Twenty years later in 1990, marriage rates for most countries had decreased to between 5.0 and 6.0. The general trend into the new century has been a continuing decrease in marriage rates to between 3.0 and 4.0. However, there have been a few exceptions where the marriage rate has increased over the last 10 years in Sweden, Finland, and Greece. There is a clear connection between the decline in marriage rates and postponement of marriage. This means that some of the declines in marriage rates are due to people postponing marriage, so a reversal may have a “catching-up” effect. A recent study of the reverse marriage trend in Sweden suggests that the popularity of marriage in Sweden is increasing (Ohlsson-Wijk, 2011). As a forerunner of new family behavior and the first country in which young people started to postpone marriage, Sweden makes an interesting case study. When marriage is no longer the conventional form of union formation based on social norms and values, people are marrying for other reasons, and marriage can be seen as a manifestation of individual values and preferences (Sobotka and Toulemon, 2008). An interesting question is whether other countries will also experience a similar marriage turnaround in the future. It has been argued that the symbolic value of marriage may still be high even though its practical importance has decreased (Cherlin, 2004). Thus, marriage may mark a new stage in couple’s relationships and may symbolize its distinction from cohabitation (Noack, Berhardt, and Wiik, 2013).

Table 2.1 Total period marriage rates 1970–2010 for selected European countries

Source: Data from Eurostat.

| Country | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 |

| Ireland | 7.0 | 6.4 | 5.1 | 5.0 | 4.6 |

| France | 7.8 | 6.2 | 5.1 | 5.0 | 3.8 |

| Sweden | 5.4 | 4.5 | 4.7 | 4.5 | 5.3 |

| Norway | 7.6 | 5.4 | 5.2 | 5.0 | 4.8 |

| United Kingdom | 8.5 | 7.4 | 6.6 | 5.2 | 4.3 |

| Denmark | 7.4 | 5.2 | 6.1 | 7.2 | 5.6 |

| Finland | 8.8 | 6.2 | 5.0 | 5.1 | 5.6 |

| Belgium | 7.6 | 6.7 | 6.5 | 4.4 | 3.9 |

| Netherlands | 9.5 | 6.4 | 6.5 | 5.5 | 4.5 |

| Luxemburg | 6.4 | 5.9 | 6.1 | 4.9 | 3.5 |

| Switzerland | 7.6 | 5.6 | 6.9 | 5.5 | 5.5 |

| Greece | 7.7 | 6.5 | 5.8 | 4.5 | 5.0 |

| Bulgaria | 8.6 | 7.8 | 6.8 | 4.3 | 3.2 |

| Czech Republic | 9.2 | 7.6 | 8.8 | 5.4 | 4.4 |

| Austria | 7.1 | 6.2 | 5.9 | 4.9 | 4.5 |

| Italy | 7.4 | 5.7 | 5.6 | 5.0 | 3.6 |

| Germany | 7.9 | 6.3 | 6.5 | 5.1 | 4.7 |

| Spain | 7.3 | 5.9 | 5.7 | 5.4 | 3.6 |

| Portugal | 9.4 | 7.4 | 7.2 | 6.2 | 3.8 |

| Hungary | 9.4 | 7.5 | 6.4 | 4.7 | 3.6 |

Same-sex marriage

Same-sex marriage is the newest type of family formation. It did not exist before the twenty-first century, but has emerged in several countries over the last decade. Legalizing same-sex marriage has been more controversial in some countries than others. Before same-sex marriages were legalized, the Nordic countries and the Netherlands introduced the so-called registered partnership where same-sex couples were given more or less the same legal rights and duties as heterosexual marriages (Noack, Berhardt, and Wiik, 2013). Since 2000, same-sex marriages have been legalized in seven European countries: the Netherlands (2001), Belgium (2003), Spain (2005), Norway and Sweden (2009), and Iceland and Portugal (2010) (Chamie and Mirkin, 2011). Same-sex marriages have also been legalized in Canada and some states in the United States.

In European countries, same-sex marriages constitute a very small proportion of all marriages. The proportion was somewhat larger in the first year following its legislation but is now in the range of 1.8% (Spain) and 3.2% (Sweden) (Chamie and Mirkin, 2011). Some analyses have shown that same-sex marriages in Scandinavia are somewhat different to heterosexual marriage in that couples are older when they marry and female couples have a higher divorce risk than male couples (Andersson et al., 2006; Andersson and Noack, 2010).

The increase in childbearing in cohabitation

Following the increase in unmarried cohabitation among young people, there has been a dramatic rise in childbearing in cohabitation. With a few exceptions, official statistics in most countries have not picked up on these trends and are still publishing only the proportion of births outside marriage. The vast majority of the increases in births have been in cohabiting couples, rather than to single mothers (Perelli-Harris et al., 2010). Childbearing outside any union constitutes 5% of births observed in Italy, Spain, and Switzerland; about 10% in Norway, West Germany, and the United Kingdom; and about 20% in the United States and Austria (Kennedy and Bumpass, 2008; Sobotka and Toulemon, 2008).

Figure 2.1 shows the proportions of births outside marriage in 1970, 1985, 2000, and 2010 for European countries. There has been a clear increase in nonmarital childbearing in all nations, but there are extensive variations across nations in the level of nonmarital childbearing and in the time period during which the changes occurred. Before 2000, there was a clear North–South divide. The highest proportions of births outside marriage were found in the Nordic countries where 50% of all births were nonmarital, while the lowest proportions were found in Southern European countries, for example, Greece, where still less than 10% of children were born outside marriage. After 2000, only small changes appeared in the Nordic countries, with Iceland and Sweden experiencing small decreases, whereas more countries had reached 50%. For instance, France increased from 43% in 2000 to 54% in 2010. During the last 40 years, countries have followed different trajectories in the increase of nonmarital childbearing. Among the Nordic countries, Iceland and Sweden had reached a level of almost 20% or higher already in 1970, while Norway had a lower level from the outset and increased at a slower pace until 2000. Another group is France, the United Kingdom, and Bulgaria, which have almost reached the same level as the Nordic countries. These countries had their most rapid increase in the period 1985 to 2000, where the level continued to increase after 2000. The next group is the Netherlands, the Czech Republic, and Austria, which have now reached a level of 40% or more; the Netherlands and the Czech Republic have increased rather rapidly over the last 10 years. Austria is somewhat different in already having a relatively high proportion (13%) in 1970 and increasing more gradually. Southern European countries have witnessed more variation in the last decade. While Greece has experienced only small changes, there have been rather rapid increases in both Italy and Spain, with Spain having already started to increase in the period 1985–2000.

Figure 2.1 Percentage of births outside marriage 1970–2010 for selected European countries.

Source: Data from Eurostat.

New research has shown that childbearing in cohabitation across Europe is associated with a negative educational gradient, that is, cohabiting women with low levels of education (less than completed basic secondary school) have a significantly greater risk of first births than women with medium levels of education (completed secondary school and any school beyond secondary school but less than completed college), while cohabiting women with high levels of education (bachelor’s or university degree or higher) have a significantly lower risk (Perelli-Harris et al., 2010). These authors interpret this as a “pattern of disadvantage.” Across Europe, life has become more uncertain in the labor and housing markets. Young people have responded to these conditions by postponing family-related events including leaving the parental home, marrying, and childbearing (Kohler, Billari, and Ortega, 2002; Sobotka and Toulemon, 2008). Perelli-Harris et al. (2010) argue that if cohabitation can be linked to this uncertainty, “marriage signifies stability, and the least educated have been the most severely affected by economic uncertainty and globalization, then it seems to follow that the least educated would be more likely to cohabit, while the most highly educated would be more likely to marry. This association should become even more pronounced at the birth of a couple’s first child, when the stability of marriage and the commitment of two parents may be perceived as especially crucial for childrearing” (2010, p. 796).

Childbearing and marriage

The increase in childbearing in cohabitation raises the question of the role of marriage in the childbearing process. When cohabitation functions as a stable relationship for raising children, marriage may become more irrelevant (Heuveline and Timberlake, 2004; Kiernan, 2004). The fact that most children born into cohabitation will experience the marriage of their parents (Heuveline and Timberlake, 2004) indicates that marriage and childbearing continue to be interrelated, although in a manner different to previously. When the normative pressure to follow the standard sequencing of marriage followed by childbearing becomes weaker, it might lead to a greater variety in sequences of events (Billari and Liefbroer, 2010). The perception of what constitutes a family has also changed. Kiernan’s (2004) analysis of 1998 Eurobarometer data shows that children, rather than partnership status, appear to be more salient in defining families.

To understand the meaning of marriage vis-à-vis childbearing, four categories of marriage have been proposed by Holland (2013). In the first category, the standard sequence of marriage and then children, defined as the family-forming marriage, follows normative thinking that childbearing should take place in marriage. Marriage that occurs in tandem with or shortly after the beginning of childbearing is defined as a legitimizing marriage. The so-called “shotgun” marriage or bridal pregnancy has become less common, but marriages occurring shortly after the birth of a child can be placed into this category. In the next category, marriage is not seen as necessary for childbearing, and the transition to parenthood is viewed as a stronger relationship commitment than marriage. However, marriage may be seen as indicating reinforcement of the marriage contract as a formalization of the commitment and adds an additional layer of security to the union. Finally, marriage is seen as the capstone of the family-building process and occurs when the couple has achieved a desired family size.

In new analysis, Perelli-Harris et al. (2012) show how childbearing is interrelated with marriage and cohabitation. As presented in Table 2.2, they followed a subsample of women who had their first birth within a union. Their results show the percentage of women who were cohabiting with the father of their first child, the percentage of these women who were cohabiting at conception and birth, and the proportion of women who were cohabiting 1 and 3 years after birth. For the last two columns in Table 2.2, both marriage and dissolution were possible alternatives. First, the results confirm that across Europe cohabitation has become the most common way of starting a union that produces children, with a few exceptions. Second, in most countries, most cohabitation that involves childbearing couples still moves into marriage before the birth of the first child. This is the period of the most changes. Third, couples who are cohabiting at the first birth make fewer changes later and are more likely to continue cohabiting as they did before the birth. For all the countries included in this study, cohabitation may still be regarded as a temporary state, at least when childbearing is involved (Perelli-Harris et al., 2012). Following the categories proposed by Holland (2013), it is clear that family-forming marriage and legitimizing marriages are most present across Europe. This pattern is less evident in Norway, which together with the other Nordic countries is often described as the forerunner in family change. Using another approach, similar distributions are found for Sweden, another forerunner in new family behavior (Holland, 2013).

Table 2.2 Among women who gave birth within a cohabiting or marital union, the percentage remaining within cohabitation at different stages in the life course in 11 European countries, 1995 to the early 2000s

Source: Data from Perelli-Harris et al. (2012).

| Start of union | Conception | First birth | One year after birth | Three years after birth | ||

| Percent of women who began their unions with cohabitation | Percent still cohabiting at conception | Percent still cohabiting at birth | Percent of women in cohabitation 1 year after birth, based cumulative incidence curves | Percent of women in cohabitation 3 years after birth, based cumulative incidence curves | Percent who started union with cohabitation and stayed in cohabitation up to 3 years after birth | |

| Norway | 90 | 61 | 56 | 49 | 35 | 39 |

| France | 90 | 51 | 47 | 41 | 33 | 37 |

| Austria | 88 | 55 | 38 | 30 | 23 | 27 |

| Netherlands | 78 | 33 | 26 | 25 | 22 | 28 |

| United Kingdom | 75 | 34 | 26 | 22 | 15 | 20 |

| Bulgaria | 77 | 45 | 24 | 21 | 20 | 26 |

| Russia | 57 | 40 | 18 | 13 | 8 | 14 |

| Hungary | 46 | 28 | 18 | 17 | 15 | 33 |

| Romania | 29 | 18 | 12 | 9 | 7 | 24 |

| Italy | 18 | 10 | 8 | 7 | 4 | 22 |

Transition to Parenthood

Becoming parents is one of the most important decisions couples make and has become an important way of expressing partnership commitment. Better access and improved contraception have made couples and especially women more able to choose when and how many children they want. Young people wait longer until they become parents and have fewer children than in the past. To better understand changing fertility trends across Europe, three main features are explored: the diversity of family behavior, gender equality, and family policy.

Fewer and later childbirths

Throughout Europe, there is great concern for present fertility levels and trends. Since the 1960s, birth rates across Europe have dropped dramatically, and fertility below replacement levels has captured the attention of researchers, policy makers, and society at large. Low fertility puts more pressure on the welfare state by increasing the age-dependency ratio, thus also creating a larger burden for future generations. Total Fertility Rate (TFR) is the main indicator of fertility. TFR is the mean number of children born alive to a woman during her life course under the provision that the childbearing pattern in the period applies to the woman’s entire reproductive period. A TFR of around 2.1 children per woman is considered to be the replacement level, that is, the average number of children per woman required to keep the population size constant in the absence of migration.

Table 2.3 shows the TFR across Europe for the period 1970–2010. Currently, the highest rates are in Ireland, France, the United Kingdom, and the Nordic countries, and the lowest rates are to be seen in Central and Southern European countries. In the trend of decreased fertility across Europe, many countries have experienced fertility rates at “very low” (below 1.5) or “lowest low” (below 1.3) levels (Frejka and Sobotka, 2008). Since 2000, fertility levels seem to be increasing in almost all countries, albeit slightly. This may be partly due to a catching-up process, following postponement of having children. Since the beginning of the 1970s, women across Europe, especially in Western Europe, have been postponing motherhood. In the early 1970s, the average age at first birth for most Western European women was 23–24 years, while in 2000, it was 27–28 years (Council of Europe, 2005). Since 2000, women have still been postponing childbirth, but there are some signs of stabilization with a lessening pace of postponement. For instance, during the 1990s, the mean age at first birth increased by 1.8 years among Norwegian women, while it only increased by 0.8 years during the 2000s. Numbers for men are rare, but in general, they are following the same movement at slightly higher ages. There is little evidence that delayed entry into parenthood plays a significant role in the shifts toward low and very low fertility levels in many parts of Europe (Frejka and Sobotka, 2008).

Table 2.3 Total period fertility rates 1970–2010 for selected European countries

Source: Data from Eurostat.

| Country | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 |

| Ireland | 3.85 | 3.21 | 2.11 | 1.89 | 2.07 |

| France | 2.47 | 1.95 | 1.78 | 1.89 | 2.03 |

| Sweden | 1.92 | 1.68 | 2.13 | 1.54 | 1.98 |

| Norway | 2.50 | 1.72 | 1.93 | 1.85 | 1.95 |

| United Kingdom | 2.45 | 1.90 | 1.83 | 1.64 | 1.94 |

| Denmark | 1.95 | 1.55 | 1.67 | 1.77 | 1.87 |

| Finland | 1.83 | 1.63 | 1.78 | 1.73 | 1.87 |

| Belgium | 2.25 | 1.68 | 1.62 | 1.67 | 1.84 |

| Netherlands | 2.57 | 1.60 | 1.62 | 1.72 | 1.79 |

| Luxemburg | 1.97 | 1.50 | 1.60 | 1.76 | 1.63 |

| Switzerland | 2.10 | 1.55 | 1.58 | 1.50 | 1.50 |

| Greece | 2.40 | 2.23 | 1.40 | 1.26 | 1.51 |

| Bulgaria | 2.17 | 2.05 | 1.82 | 1.26 | 1.49 |

| Czech Republic | 1.92 | 2.08 | 1.90 | 1.14 | 1.49 |

| Austria | 2.29 | 1.65 | 1.46 | 1.36 | 1.44 |

| Italy | 2.38 | 1.64 | 1.33 | 1.26 | 1.41 |

| Germany | 2.03 | 1.56 | 1.45 | 1.36 | 1.39 |

| Spain | 2.88 | 2.20 | 1.36 | 1.23 | 1.38 |

| Portugal | 3.01 | 2.25 | 1.56 | 1.55 | 1.36 |

| Hungary | 1.98 | 1.91 | 1.87 | 1.32 | 1.25 |

Childlessness

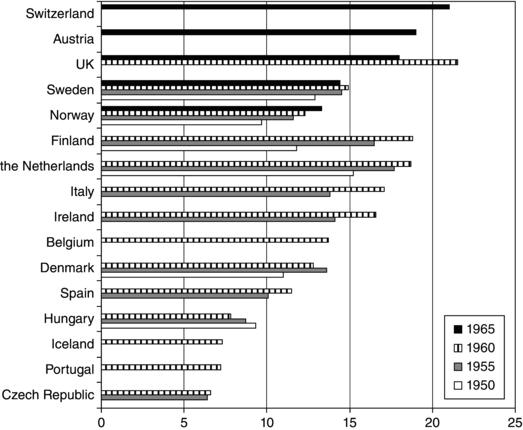

Parallel to the trend in young people of postponing parenthood is a trend of increased childlessness. As illustrated in Figure 2.2, 10–20% of women born in 1950–1965 will never have children. The highest numbers are found in Austria, Finland, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom, where about one in five women born in either 1960 or 1965 is childless. Data for men are relatively rare; however, in Norway and Sweden where such data are available, higher proportions of men relative to women in the same cohorts are childless. More than one in five men born in 1960 had not fathered a child. These numbers are based on reliable register data and not a result of poor quality or missing data on men’s fertility histories. Childlessness is a concern not only because of its implications for maintaining stable populations but also because it has consequences for individuals, including access to support in old age (Dykstra and Hagestad, 2007; Rowland, 2007).

Figure 2.2 The proportion of childless women at age 40, women born 1950–1965, selected European countries.

Source: Data from OECD; Statistics Sweden; Statistics Norway.

Delaying parenthood has been seen as a strategy, especially among women, to pursue goals such as higher education, become established in the labor market, and accumulate material resources (Sobotka, 2005). Using period and cohort fertility data for 17 European countries and the United States, Sobotka (2005) analyzed and projected trends in final childlessness among women born between 1940 and 1975. Although final childlessness will gradually increase across all European countries, there will be national variations in the magnitude of these changes. The Nordic countries and France have relatively low childlessness compared with other European countries. Sobotka argues that the generous family policies typical in these countries may have an enabling effect as “by reducing some constraints child rearing imposes upon people’s lives, they enable more couples to decide to become parents” (Sobotka, 2005, p. 28).

The social acceptance of childlessness has increased over time. Using data from the 2006 European Social Survey, Merz and Liefbroer (2012) show that approval of voluntary childlessness was highest in Northern, followed by Southern Europe and lowest in former communist Eastern European countries. They also find that approval of childlessness is related to advancement in the second demographic transition. According to this theory, increased emphasis on autonomy and self-realization lead to greater acceptance of new demographic behavior that deviates from traditional family norms (Lesthaeghe, 2010). There is an important gender dimension in attitudes toward childlessness where Merz and Liefbroer (2012) also find that women are more approving of voluntary childlessness than men and the educational gradient in approval of childlessness is steeper for women.

The diversity of family behavior and fertility

An appropriate line of inquiry is to examine linkages between changing fertility trends and the diversity of family behavior across Europe. It is argued that one of the central parts of the second demographic transition, the decline in marriage rates, cannot be considered an important cause of the current low fertility levels in many European countries (Sobotka and Toulemon, 2008). Nowadays, we observe a positive correlation between fertility rates and unmarried cohabitation; there are higher fertility rates in countries with higher proportions of unmarried cohabitation than in countries where cohabitation is rarer. As union dissolution and divorce increase across Europe, more people reestablish themselves in new family unions following family dissolution. Consequently, more children are born within a stepfamily union, and more people have children with more than one partner (multipartnered fertility). These phenomena raise the question of whether the formation of new unions produces “extra” births, that is, children who would not have been born if the woman had remained in a stable union. So far, scattered evidence suggests that birth chances are elevated when the prospective child will be the new couple’s first or second common offspring, indicating that the unique value of a first or second shared child exceeds the costs of rearing a larger number of children in stepfamilies (Thomson, 2004). Only a few studies show the prevalence of multipartnered fertility across Europe. Estimates from Danish register data indicate that about 10% of fathers aged 38 or older have had children with more than one mother (Sobotka, 2008), while estimates from Norway show an increase in the proportion of men who have had children with more than one mother, from less than 4% of those born before World War II to about 11% of those born in the early 1960s (Lappegård, Rønsen, and Skrede, 2011).

Gender equality and fertility

Gender practices in paid and unpaid work have changed over the past decades. In most Western countries, there has been a move away from the traditional male breadwinner model toward various degrees of dual-earner models in which both men and women participate in the labor market. An essential question is whether gender equality matters for fertility. Low fertility is often seen as the result of gender inequality in areas of life that have been recognized as essential for childbearing in modern societies, namely, employment, economic resources, and household and care work. The European Commission recognizes that the future of the welfare states depends on women’s willingness to insure a reproduction function and proposes a wide range of policies to improve the possibilities for women and men to found a family, including financial support and work arrangements (European Commission, 2007).

In previous decades, low fertility in industrialized countries has been linked to increasing female labor force participation (Becker, 1981). More recently, the relationship seems to have reversed, and there is a positive macrolevel correlation between female work in the labor market and fertility. To illustrate this, Figure 2.3 shows the correlation between the percentage of women aged 25–54 who are found in the labor force and the TFR. There is a clear South–North division, where the Nordic countries have both high fertility levels and high proportions of women in the labor force, while in Southern European countries, there is both low fertility and low female labor force participation. Eastern European countries also have low fertility but have a longer history of female employment. In the countries where we can see a positive fertility reversal, gender equality is also very high. In some countries, the gender egalitarian model has become the norm, that is, the political goal of gender equality is implemented through welfare state interventions in family arrangements. Fertility in these countries is also high. The Nordic countries are suitable examples since they generally score high on gender equality indexes such as the UN gender empowerment measurement and have relatively high fertility compared with other industrialized countries. These phenomena might be explained by the Beckerian model where improved female empowerment predicts fertility decline (Becker, 1981), but as we move toward the egalitarian model where the dual-earner couple is the norm, gender equality might generate higher fertility.

Figure 2.3 The correlation between the percentage of females in the work force (aged 25–54) and total fertility rate 2010 for selected European countries.

Source: Data from Eurostat.

Most modern societies are moving toward higher gender equality, a process often referred to as the “gender revolution.” Many describe this as a two-step process, with the first step being developing gender equality in education and employment and better integration of women in the political process. This is followed by higher gender equality in the private sphere of the family (Goldscheider, Oláh, and Puur, 2010), implying that men take a more active role in the family, that is, participation in housework and childcare. Where the process of gender equality within the family sphere is not occurring at the same pace as gender equality at the societal level, families are put under pressure, thereby limiting fertility (Goldscheider, Oláh, and Puur, 2010). A similar argument is made by McDonald (2000); low fertility in developed countries is the result of a high level of gender equality in individual-oriented social institutions, for example, the educational system and the labor market, and a low level or at best a moderate level of gender equality in family-oriented institutions, especially in the family.

Family policy and fertility

The possible relationship between policies of parenthood and fertility has been the subject of increasing interest over the past decades. The Nordic combination of high levels of female labor force participation and relatively high levels of fertility has prompted the notion that family policies play a role in generating this situation.

The link between public policy and demographic behavior is very complex (Gauthier, 2007; Neyer and Andersson, 2008) and depends on the type of policies, the level of benefits, the conditions of eligibility, and the broader context of economic, social, and political development. Not surprisingly, therefore, the findings of previous research in this area vary. Some early studies based on macrodata from the early 1970s and 1980s suggested a certain positive policy effect, but similar analyses from the 1990s and later, when most European countries had a wider range of family policies in place, present less clear results (for overviews, see, e.g., Neyer, 2003; Gauthier, 2007).

As a consequence, many researchers maintain that family policy interventions have uncertain or at best marginal effects on fertility. Other researchers argue that policy effects on fertility cannot be properly assessed using aggregate data and that individual-level data are needed to measure the impact on individual behavior. An increasing body of such research suggests that family policies can affect childbearing behavior. Most well known is probably the so-called “speed premium” effect in Sweden (Hoem, 1990; Andersson, 2004). This is a unique feature of the Swedish parental leave system that has encouraged mothers to space their childbirths more closely together. Evidence from Norway indicates that there may be a slight positive effect on fertility of increasing day-care supply (Rindfuss et al., 2007). Studies from other parts of Europe also suggest that family policies play a role in fertility decisions. For Italy, Del Boca (2002) finds that the availability of childcare and part-time work increases both the probability of working and having a child; estimates for France suggest that fertility is quite sensitive to financial incentives in the French family benefit package (Laroque and Salanié, 2008).

Family Dissolution

While staying together until separated by death is the norm, marriages are increasingly dissolving, resulting in more diverse living arrangements and family forms including more people living alone for longer periods, more parents living as single parents, and more people repartnering. This may have consequences not only for the parents (mostly the fathers) who are not living full time with their children but also for children’s welfare.

Increasing and decreasing divorce rates

Nowadays, all European countries experience higher divorce rates than they did just a few decades ago. During this period, there have been considerable changes in divorce policy and divorce laws. Throughout Europe, there are large differences in the tempo of the increase and the level of divorce rates, and some countries have even experienced a reversal trend over the last 10 years. This is illustrated in Figure 2.4, which shows the number of divorces per 1000 population for several European countries for the period 1975–2010. Many countries experienced a major increase in the divorce rates in the 1970s (e.g., the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Norway, Germany, Belgium, and France) and reached a level of 2.0 or above in 1985. Sweden, Austria, and the Czech Republic already had higher levels in 1970 but were found to have higher levels in 1985. In 1985, the highest levels were found in the United Kingdom and the Czech Republic with 2.8 and 2.9, respectively. The Czech Republic continued this high level in 2000 and 2010, while the United Kingdom together with several other countries has experienced a decrease in the divorce rates, especially since 2000. Divorce rates started to increase somewhat later in both Spain and Portugal, but they have now reached divorce rates at the higher end of the scale. Poland, Italy, and Greece also experienced an increase in divorce rates, but not to the same level as other European countries. These trends show that there is no consistent East–West differentiation in divorce rates as there were in other indicators of family behavior (Sobotka and Toulemon, 2008). Consequently, as cohabitation is increasingly gaining ground across Europe, it becomes more difficult to interpret divorce rates, especially the decrease that we can observe in parts of Europe. As more couples start unmarried cohabitation, there is more selection into marriage as many of the less committed couples break up before they enter marriage.

Figure 2.4 Crude divorce rates per 1000 population 1970–2010 for selected European countries.

Source: Data from Eurostat.

There are few available data on trends in separation among unmarried cohabitants, mainly because it is an informal behavior; only a few countries have the option to register cohabitation as a living arrangement, for example, the Netherlands. Generally, cohabiting unions have a higher breakup risk than marriage, especially when there are no children involved but also when the couple has common children. Using data from the Fertility and Family Survey 1989–1997, Andersson (2002, 2003) compared disruption risks depending on the family status at childbirth. He finds that children born within cohabitation have higher disruption risks than children born in marriage, but the differences between cohabitation and marriage are smaller in Sweden where the level of childbearing in cohabitating couples was the greatest. This indicates that when childbearing in cohabitation becomes more common, cohabiting unions with children become a less selective group and more similar to married couples in union stability.

Interestingly, people’s acceptance of divorce does not follow divorce rates as one may expect (Rijken and Liefbroer, 2012). The authors argue that “the idea that the more one is exposed to a type of new behavior, the more tolerant one’s attitudes towards this type of behavior become, may not be applicable if the behavior is evaluated as largely negative” (Rijken and Liefbroer, 2012, p. 43). There are, however, two characteristics of a country that they find correlate with acceptance of divorce involving young children. First, the poverty rate among single-parent households is negatively associated with acceptance of divorce involving young children. Second, higher enrolment in childcare is positively associated with acceptance of divorce involving young children. This means that the financial consequences for the single parent, mostly the mother, are a factor people take into account when forming attitudes toward divorce. In addition, childcare protects children’s upbringing and provides mothers with opportunities for paid work (Rijken and Liefbroer, 2012).

Single-parent families

A consequence of higher divorce rates is more children not living with both parents. As illustrated in Table 2.4, there is great variation across Europe. Data from the Health Behavior in School-Aged Children Survey 2005/2006 report on children aged 11, 13, and 15 combined show that, among the countries included here, Italy has the highest proportion of children living with both parents (87%) and Denmark the lowest (66%). The majority of children not living with their parents are living with one parent, most likely their mother. There is considerable diversity in the distribution of children living in single-parent families compared with stepfamilies. In Italy, the proportion of single parents is 67% and in Denmark 37%, with the rest living in stepfamilies. The higher prevalence of stepfamilies compared with single-parent families is more pronounced in countries where the proportion not living with both parents is greater. This indicates that repartnering or remarrying is more common in countries where family dissolution is more common.

Table 2.4 Family structure for children aged 11, 13, and 15 combined, 2005/2006, for selected European countries

Source: Data from Health Behaviour in School-aged Children Survey 2005/2006 in Chapple 2009.

| Country | Both parents | Single parent | Stepfamily | Other |

| Italy | 87 | 9 | 3 | 1 |

| Greece | 86 | 11 | 2 | 1 |

| Spain | 84 | 11 | 4 | 1 |

| Poland | 83 | 12 | 3 | 1 |

| Portugal | 82 | 10 | 6 | 2 |

| Ireland | 81 | 13 | 5 | 2 |

| Netherlands | 80 | 12 | 7 | 1 |

| Switzerland | 79 | 12 | 8 | 1 |

| Austria | 76 | 14 | 8 | 1 |

| Luxemburg | 76 | 14 | 8 | 2 |

| Belgium (Flemish) | 74 | 14 | 10 | 1 |

| Germany | 74 | 15 | 9 | 1 |

| Hungary | 74 | 16 | 9 | 2 |

| France | 73 | 14 | 11 | 1 |

| Norway | 73 | 16 | 10 | 2 |

| Sweden | 73 | 14 | 12 | 1 |

| Finland | 71 | 16 | 13 | 1 |

| Czech Republic | 70 | 16 | 12 | 2 |

| United Kingdom (England) | 70 | 16 | 12 | 1 |

| Denmark | 66 | 19 | 13 | 3 |

One of the consequences of family dissolution and divorce is that one of the parents is not living, at least not full time, with their children. This is often the father as mothers are more likely to have their children living with them on a daily basis after separation or divorce. On the other hand, more repartnering means that more adults – also more so among men – are living in families with children who are not their biological children. Family dissolution may have a direct consequence for the welfare of children. Single-parent families are less likely to have as much income as families of both parents. Separation often means the direct loss of a family earner but may also increase the difficulty and cost for the custodial parent in supplying labor and generating income.

Discussion

Family behavior across Europe is changing. Most countries are following the same trends, but there is extensive variation in level and tempo of change. Decreasing marriage rates and fertility rates, increasing divorce rates, and more children born within cohabitation indicate that “new” family behavior is becoming more popular across Europe. There is also a general postponement of family events, that is, increasing ages of transition to marriage and parenthood, but also more variation, indicating a diverging pattern of timing and sequencing of events (Billari and Liefbroer, 2010). In this chapter, we have seen how these changes vary over time and across nations. In this discussion, I will raise two issues from this review, namely, the relationship between marriage and childbearing and the situation with low fertility across Europe.

The most profound changes are the disconnection of marriage and childbearing and family events not following a traditional sequence. This raises two main questions concerning the role that marriage will have in the future and whether there are different consequences for children born within or outside marriage. The main role of marriage as an institution has been the ritual of forming a new couple (Heuveline and Timberlake, 2004) and as a way to sanction the link between parents and their children (Sobotka and Toulemon, 2008). As most young couples nowadays start living together outside marriage and more children are born within cohabitation, the meaning of marriage has changed. Marriage is perceived as a private matter, and couples are entering marriage at different stages in the family formation process. Even though cohabitation is practiced as an alternative to marriage in some groups, most couples eventually marry. As we have seen in this chapter, marriage remains the main context for raising children, and most children will experience their parents being married. For some, marriage remains the main arena for childbearing, and for others, marriage is a capstone to the family formation process (Holland, 2013). When cohabitation becomes completely accepted and there are no legal differences in marriage and cohabitation, an appropriate question is: why do couples still choose to marry? The fact that Sweden, one of the forerunners in new family behavior, is witnessing a reverse marriage trend makes this question even more relevant. In the future, there is a need for more research and new theories about the changing meaning of marriage and the role of cohabitation in the family formation process.

Does it matter whether children are born within or outside marriage? The main distinction is whether a child is born to a single mother, not whether he/she is born to cohabiting or married parents. There is evidence that cohabiting unions are more fragile than marriage, also when children are involved. However, the differences are smaller in countries where cohabitation is more common. The prevalence of cohabitation and childbearing in cohabitation is generally associated with changing values and norms that are more accepting of new family behavior (Lesthaeghe, 2010). However, as we have seen in this chapter, childbearing in cohabitation is associated with a negative educational gradient also in countries where cohabitation is more common, suggesting also a pattern of disadvantage (Perelli-Harris et al., 2010). In the future, there is a need for more research on how different social groups are adapting new family behaviors and the meanings given to cohabitation and marriage by different groups.

Lower fertility has been part of the shift in family behavior, but some countries have lower fertility levels than others and there are real concerns for the imbalance in the age structure and the consequences of low fertility. Young people still have a strong desire to have children, and having children together seems to be a more important expression of relationship commitment for couples than marriage. The decision about having children is embedded in economic, structural, and normative conditions. It is not difficult to imagine that it would be easier to bring a child into the world when certain aspects are in order, such as having a decent place to live and having a stable and economically secure job. For many women, the prospect of being able to remain in the labor market after childbirth may also be of importance. In some countries, the state has become a central actor in the sense that they provide families with economic compensation for the cost of having children and offer childcare to parents. The debate continues over whether the state should spend money on children and to what extent they should make arrangements for families that reconcile family and work life. At an aggregate level, there is a positive correlation between the use of family policies and fertility rates in Europe. There is still a need for more research on how these mechanisms are working and whether arrangements that are working in some societies can be transferred to others.

To conclude, European families are changing in terms of more diverse ordering of life events and continued postponement of events. Despite some variations, countries appear to be following similar trajectories in how partnership and parenthood are organized.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the Research Council of Norway and constitutes a part of the research project “Family dynamics, fertility choices, and family policy” (202442/S20). We would like to thank Jennifer Holland, Netherlands Interdisciplinary Demographic Institute (NIDI); Gerda Neyer, Stockholm University; Turid Noack, Statistics Norway; and Tomáš Sobotka, Vienna Institute of Demography for valuable insights.

References

- Andersson, G. (2002) Children’s experience of family disruption and family formation: evidence from 16 FFS countries. Demographic Research, 7, 343–364.

- Andersson, G. (2003) Dissolution of unions in Europe: a comparative overview. MPIDR working paper WP2003–004, Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, Rostock.

- Andersson, G. (2004) Childbearing developments in Denmark, Norway and Sweden from 1970s to the 1990s: a comparison. Demographic Research, 3, 155–176.

- Andersson, G. and Noack, T. (2010) Legal advances and demographic developments of same-sex unions in Scandinavia. Zeitschrift für Familienforschung (Journal of Family Research), 22 Sonderheft, 87–101.

- Andersson, G., Noack, T., Seierstad, A. and Weedon-Fekjær, H. (2006) The demographics of same-sex marriages in Norway and Sweden. Demography, 43, 79–98.

- Becker, G. (1981) A Treatise on the Family, Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

- Billari, F.C. and Liefbroer, A.C. (2010) Towards a new pattern of transition to adulthood. Advances in Life Course Research, 15, 59–75.

- Bumpass, L.L. (1990) What’s happening to the family? Interactions between demographic and institutional changes. Demography, 27, 483–498.

- Chamie, J. and Mirkin, B. (2011) Same-sex marriage: a new social phenomenon. Population and Development Review, 37, 529–551.

- Chapple, S. (2009) Child Well-Being and Sole-Parent Family Structure in the OECD: an Analysis. OECD social, employment and migration working paper, no. 82, OECD, Paris.

- Cherlin, A.J. (2004) The deinstitutionalization of American marriage. The Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 848–861.

- Council of Europe (2005) Recent Demographic Developments in Europe, Council of Europe, Strasbourg.

- Del Boca, D. (2002) The effect of child care and part time opportunities on participation and fertility decisions in Italy. Journal of Population Economics, 15, 549–573.

- Dykstra, P.A. and Hagestad, G.O. (2007) Roads less taken: developing a nuanced view of older adults without children. Journal of Family Issues, 28, 1275–1310.

- European Commission (2007) Europe’s Demographic Future: Facts and Figures on Challenges and Opportunities, Office of Official Publications of the European Communities, Luxembourg.

- Frejka, T. and Sobotka, T. (2008) Overview chapter 1: fertility in Europe: diverse, delayed and below replacement. Demographic Research, 19, 15–46.

- Gauthier, A.H. (2007) The impact of family policies on fertility in industrialized countries: a review of the literature. Population Research and Policy Review, 26, 323–346.

- Giddens, A. (1992) The Transformation of Intimacy. Sexuality, Love & Eroticism in Modern Societies, Polity Press, Cambridge.

- Goldscheider, F., Oláh, L.S. and Puur, A. (2010) Reconciling studies of men’s gender attitudes and fertility: response to Westoff and Higgins. Demographic Research, 22, 189–198.

- Heuveline, P. and Timberlake, J.M. (2004) The role of cohabitation in family formation: the United States in comparative perspective. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 1214–1230.

- Hoem, J.M. (1990) Social policy and recent fertility change in Sweden. Population and Development Review, 16, 735–748.

- Holland, J.A. (2013) Love, marriage, then the baby carriage? Marriage timing and childbearing in Sweden. Demographic Research, 20 (11), 275–306.

- Kennedy, S. and Bumpass, L. (2008) Cohabitation and children’s living arrangements: new estimates from the United States. Demographic Research, 19, 1663–1692.

- Kiernan, K. (2004) Unmarried cohabitation and parenthood in Britain and Europe. Law & Policy, 26, 33–55.

- Kohler, H-P., Billari, F.C. and Ortega, J.A. (2002) The emergence of lowest-low fertility in Europe during the 1990s. Population and Development Review, 28, 641–680.

- Lappegård, T., Rønsen, M. and Skrede, K. (2011) Fatherhood and fertility. Fathering: A Journal of Theory, Research, and Practice about Men as Fathers, 9, 103–120.

- Laroque, G. and Salanié, B. (2008) Does Fertility Respond to Financial Incentives? Discussion paper no. 5007, Centre for Economic Policy Research, London.

- Lesthaeghe, R. (1995) The second demographic transition in western countries: an interpretation, in Gender and Family Change in Industrialized Countries, (ed. K.O. Mason and A.-M. Jensen), Clarendon Press, Oxford, pp. 17–62.

- Lesthaeghe, R. (2010) The unfolding story of the second demographic transition. Population and Development Review, 36, 211–251.

- Liefbroer, A.C. and Dourleijn, E. (2006) Unmarried cohabitation and union stability: testing the role of diffusion using data from 16 European countries. Demography, 43, 203–221.

- Liefbroer, A.C. and Fokkema, T. (2008) Recent trends in demographic attitudes and behaviour: is the second demographic transition moving to southern and eastern Europe? in Demographic Challenges for the 21st Century: A State of Art in Demography (ed. J. Surkyn, P. Deboosere and J. Van Bavel), VubPress, Brussels, pp. 115–141.

- McDonald, P. (2000) Gender equity in theories of fertility transition. Population and Development Review, 26, 427–439.

- Merz, E.-M. and Liefbroer, A.C. (2012) The attitude toward voluntary childlessness in Europe: cultural and institutional explanations. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 587–600.

- Neyer, G. (2003) Family policies and low fertility in Western Europe. Working paper, 2003–021, Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, Rostock.

- Neyer, G. and Andersson, G. (2008) Consequences of family policies on childbearing behaviour: effects or artefacts? Population and Development Review, 34, 699–724.

- Noack, T. (2010) En stille revolusjon: det moderne samboerskapet i Norge [A Quiet Revolution: The Modern Form of Cohabitation in Norway], University of Oslo, Oslo.

- Noack, T., Berhardt, E. and Wiik, K.A. (2013) Cohabitation or marriage? Contemporary living arrangements in the West, in Contemporary Issues in Family Studies: Global Perspectives on Partnerships, Parenting, and Support in a Changing World (ed. A. Abela and J. Walker), Wiley Blackwell, Oxford, pp.16–30.

- Ohlsson-Wijk, S. (2011) Sweden’s marriage revival: an analysis of the new-millennium switch from long-term decline to increasing popularity. Population Studies: A Journal of Demography, 65, 183–200.

- Perelli-Harris, B. and Sánchez Gassen, N. (2012) How similar are cohabitation and marriage? The spectrum of legal approaches to cohabitation across Western Europe. Population and Development Review, 38 (3), 435–467.

- Perelli-Harris, B., Sigle-Rushton, W., Kreyenfeld, M. et al. (2010) The educational gradient of childbearing within cohabitation in Europe. Population and Development Review, 36, 775–801.

- Perelli-Harris, B., Kreyenfeld, M., Sigle-Rushton, W. et al. (2012) Changes in union status during the transition to parenthood in eleven European countries, 1970s to early 2000s. Population Studies: A Journal of Demography, 66, 167–182.

- Rijken, A.J. and Liefbroer, A.C. (2012) European views of divorce among parents of young children: understanding cross-national variation. Demographic Research, 27, 25–52.

- Rindfuss, R.R., Guilkey, D., Morgan, S.P. et al. (2007) Child care availability and first-birth timing in Norway. Demography, 44, 345–372.

- Rowland, D.T. (2007) Historical trends in childlessness. Journal of Family Issues, 28, 1311–1337.

- Seltzer, J.A. (2000) Families formed outside of marriage. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 1247–1268.

- Smock, P.J. (2000) Cohabitation in the United States: an appraisal of research themes, findings, and implications. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 1–20.

- Sobotka, T. (2005) Childless societies? Trends and projections of childlessness in Europe and the United States. Paper presented at Population Association American Annual Meeting in Philadelphia, April, 2005, http://paa2005.princeton.edu/download.aspx?submissionId=50352 (accessed October 31, 2013).

- Sobotka, T. (2008) Does persistent low fertility threaten the future of European populations? in Demographic Challenges for the 21st Century: A State of Art in Demography (eds. J. Surkyn, P. Deboosere and J. Van Bavel), VubPress, Brussels, pp. 22–89.

- Sobotka, T. and Toulemon, L. (2008) Overview chapter 4: changing family and partnership behaviour: common trends and persistent diversity across Europe. Demographic Research, 19, 85–138.

- Soons, J.P.M. and Kalmijn, M. (2009) Is marriage more than cohabitation? Well-being differences in 30 European countries. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71, 1141–1157.

- Surkyn, J. and Lesthaeghe, R. (2004) Value orientations and the second demographic transition (SDT) in Northern, Western and Southern Europe: an update. Demographic Research, 3, 45–86.

- Thomson, E. (2004) Step-families and childbearing desires in Europe. Demographic Research, 3, 115–134.

- Trost, J. (1978) Attitudes toward and occurrence of cohabitation without marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family, 40, 393–400.

- Wiik, K.A., Keizer, R. and Lappegård, T. (2012) Relationship quality in marital and cohabiting unions across Europe. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 389–398.