3

American Families: Demographic Trends and Social Class

Wendy D. Manning and Susan L. Brown

American Families: Demographic Trends and Social Class

American families have undergone a radical transformation even in the last decade. A critical factor that may have influenced some of the recent change in families is the economic recession. In the wake of the recession, the middle class has become smaller, and it has become harder to maintain their standard of living (Pew Research Center, 2012a). All education groups have experienced the loss in income; however, those with only a high school degree have experienced the greatest loss (Pew Research Center, 2012a). This chapter examines recent demographic trends and specifically focuses on changes in the family according to socioeconomic status. We begin with a discussion of what constitutes a family and then provide a description of change in the timing and composition of families. Finally, we consider how those trends have differed according to social class and reflect on what this might mean for future generations.

Defining American families

A wide variety of families exist in the United States; there is certainly no singular American family. Families have been in flux, and our definitions of families have had to keep pace with increasingly common and emerging family forms. As demographers, we often rely on the US Census Bureau data and their definitions of a family. The following is used to define families in a Census Brief titled, “Households and Families: 2010” (Lofquist et al., 2012).

A family consists of a householder and one or more other people living in the same household who are related to the householder by birth, marriage, or adoption. Biological, adopted, and stepchildren of the householder who are under 18 are the “own children” of the householder. Own children do not include other children present in the household, regardless of the presence or absence of the other children’s parents.

A family household may also contain people not related to the householder. A family in which the householder and his or her spouse of the opposite sex are enumerated as members of the same household is a husband-wife household. In this report, husband-wife households only refer to opposite-sex spouses and do not include households that were originally reported as same-sex spouse households. Same-sex spousal households are included in the category, “same-sex unmarried partner households” but may be either a family or nonfamily household depending on the presence of another person who is related to the householder. The remaining types of family households not maintained by a husband-wife couple are designated by the sex of the householder.

A nonfamily household consists of a householder living alone or with nonrelatives only, for example, with roommates or an unmarried partner.

This definition does not count same-sex cohabiting couples without children or different-sex couples without children as a family. Further, cohabiting couples (same sex or different sex) that have a child in the household who is not related to the head of household (basically a stepchild to the head) are not counted as families. Most Americans have a somewhat more expansive definition of families (Powell et al., 2010). Even more recent data collected by Powell, Steelman, and Pizmony-Levy (2012) find that the presence of children continues to dramatically increase the likelihood that heterosexual cohabiting and same-sex living arrangements are counted as “family.” In addition, increasing numbers of children have more than one home, which is the result, in part, of shifts in policies determining physical custody arrangements (Kelly, 2007; National Center for Family & Marriage Research, 2012). Some states even have adopted presumption of joint custody in divorce cases. Depending on relationships, family members may “claim” children and adults who only spend part of the year living with them. Further, members of families do not always agree on who is in their family as families are perceived and constructed differently by each person (White, 1998). Specifically, research on stepfamilies indicates that there often is not consensus on who is in and out of the family (Furstenberg, 1987; Pasley, 1987; White, 1998). Along a similar vein, we find variation in mother–child dyad reports of cohabitation with at least a third of dyads not sharing the same view of their family structure (Brown and Manning, 2009). Standardization in the measurement of household relationships and families is desirable but remains challenging as families are socially constructed entities and continually shifting (Brown and Manning, 2009; National Center for Family & Marriage Research, 2012). One of the best ways to reference the contemporary family climate may be “Sustained Diversity” (Gerson, 2000).

Family change

The age at first marriage is at a historic highpoint and approaching levels observed in Europe (Elliot et al., 2012). In 2011, the median age at first marriage is 27 for women and 28.7 for men (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2012). Just in the last decade, the age at first marriage has increased by almost 2 years for both men and women. In contrast, many European countries have median ages of marriage in their 30s. The proportion of the population who has never married has also slightly increased in the last decade rising among men ages 40 to 44 from 15.7% in 2000 to 20.4% in 2010 (author’s calculations http://www.census.gov/hhes/families/data/cps2010.html Table A1 and http://www.census.gov/hhes/families/data/cps2000.html Table A1). The levels of never marrying among middle-aged Americans (45 and older) are approaching the historic highpoints observed in 1940 (Elliott et al., 2012). Currently, over one-quarter (28%) of Americans have never been married, which represents a peak over the last half a century; in 1960, 15% of Americans had never been married (Pew Research Center, 2011). The shifts in marriage are due to both delays in marriage and a modest increase in the proportion of the population who never marries. As described later, these delays in marriage provide greater opportunities for cohabiting relationships in young adulthood.

At the same time, marriage is declining among the US population; the last decade has witnessed dramatic struggles over the legalization of marriage for same-sex couples. Public opinion has shifted with nearly half of Americans as well as President Obama reporting support for same-sex marriage (Pew Research Center, 2012b). This has not been supported at the federal level but has been legally endorsed (as of March 2013) in nine states (Connecticut, Iowa, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, Vermont, and Washington) and Washington, D.C. A number of states permit civil unions and domestic partnerships, which provide many of the same protections as legal marriage; about half of same-sex couples have a legally recognized partnership option (Pizer and Kuehl, 2012). Recent estimates based on Census 2010 data indicate there are nearly 650,000 same-sex-couple households (Gates, 2012). The number of same-sex-couple households has increased by 80% over the last decade in contrast to a 40% increase in different-sex unmarried couples and 4% rise in different-sex married couples (Gates, 2012). There is little work relying on nationally representative data on the stability of these couples. About one in six (16%) same-sex-couple households includes biological, step, or adopted children, and about half of same-sex parents have only one child (Burgoyne, 2012). Same-sex couples are less likely to have children and tend to have fewer children than opposite-sex couples. Federal data collections have incorporated new ways of measuring same-sex marriage and unions in the United States (National Center for Family & Marriage Research, 2012). Yet these indicators focus on resident children in same-sex parent couple households, so single lesbian and gay parents are excluded as well as nonresident gay and lesbian mothers and fathers.

The number of different-sex cohabiting couple households has been on a steady rise with 7.5 million couples in 2010 (Kreider, 2010). The increase in age at first marriage has left more early adult years free for cohabitation, and cohabitation levels are also high following a divorce. Between 2006 and 2010, two-thirds of women ages 30–34 had ever cohabited in contrast to only 40% 25 years earlier (Manning, 2010). Increasingly, cohabitation is the first union formed by Americans rather than marriage; three-quarters (73%) of women who formed a union since 2000 cohabited rather than married first (Kennedy and Bumpass, 2011). Even though cohabiting unions are experienced by a large proportion of the population, on average, the unions do not last long. Just about half (45%) of women remained cohabiting with their first partner after 2 years (Kennedy and Bumpass, 2011). From a child’s perspective, nearly half have experienced their parents’ cohabitation, but these families are much more short-lived than marriages (Manning, Smock, and Majumdar, 2004; Kennedy and Bumpass, 2011). Cohabitation is not just a form of family life experienced by the young. An age group that has witnessed an increase in cohabitation is older Americans with a doubling between 2000 and 2010 in cohabitation among adults over the age of 50 (Brown, Bulanda, and Lee, 2012). Roughly 8% of older unmarried adults are cohabiting. The meanings and implications of cohabitation are likely different for younger and older cohabiting men and women (King and Scott, 2005; Brown, Lee, and Bulanda, 2006). While cohabitation has been integrated into much family research, there is variation in the experiences of cohabitation.

Marriage without prior cohabitation (direct marriage) is an increasingly rare event as the modal pathway into marriage is through cohabitation. Two-thirds of women who recently married had lived together prior to marriage (Manning, 2010). This represents a departure from the levels observed 25 years ago when only half of women had lived together prior to marriage (Bumpass and Sweet, 1989). Yet cohabitation is not always a promise of marriage. Fewer cohabiting unions are resulting in marriage (Kennedy and Bumpass, 2011). About one-quarter of recent cohabitations resulted in marriage within 2 years of beginning of living together in contrast to 40% a decade earlier (Kennedy and Bumpass, 2008; Kennedy and Bumpass, 2011). Further, young men and women are experiencing more cohabiting partnerships (serial cohabitation) (Lichter, Turner, and Sassler, 2010). One-quarter of a recent birth cohort of women who had cohabitation experience lived with more than one partner (Cohen and Manning, 2010). This means that young adults are spending more time not in any one cohabiting relationship but in a greater number of cohabiting relationships (Cohen and Manning, 2010). The United States appears to be moving toward patterns in Europe in terms of increases in cohabitation and declines in direct marriages. Taken together, these trends in cohabitation suggest that research needs to move away from anchoring analysis of family change around only marriage.

These changes in marriage and cohabitation patterns have not led to substantial changes in divorce. The US divorce rate is among the highest in the world, but it has plateaued (Raley and Bumpass, 2003; Kreider and Ellis, 2011). Between two-fifths and half of first marriages are expected to end in separation or divorce (Stevenson and Wolfers, 2007). In 2010, about one in seven or 14% of Americans were divorced or separated in contrast to only 5% 50 years ago (Pew Research Center, 2011). In 2009, about one-quarter (22.4%) of women were ever divorced, and the median age at first divorce was 30 (Kreider and Ellis, 2011). About one-quarter (24%) of children born to married parents are expected to experience the dissolution of their parents’ marriage by age 12 (Kennedy and Bumpass, 2011). The divorce rate among the Baby Boom generation (ages 50–64) has spiked. Today, one-quarter of those who divorce are over age 50, while 20 years ago, only 10% of those getting divorced were over age 50 (Brown and Lin, 2012). High divorce rates remain an experience unique to the United States, but increases are occurring in many countries, such as Japan and the Netherlands.

Once Americans divorce, they typically do not stay single (Sweeney, 2010). Schoen and Standish (2001) reported that 69% of women and 78% of men remarry after divorce. In 2009, the time to remarriage from divorce was about 4 years for women and men (Kreider and Ellis, 2011). In 2010, nearly one in three (30%) of marriages were remarriages (Cruz, 2012). The trend from the 1940–1944 and 1960–1964 birth cohorts suggests that similar proportions of men and women have been married at least twice (Kreider and Ellis, 2011). These remarriages are more fragile than first marriages and are more likely to end in dissolution (Teachman, 2008). The decline in remarriage after divorce has been offset by increases in postmarital cohabitation (McNamee and Raley, 2011). Thus, repartnering is an important part of the relationship landscape but has received relatively little research attention.

The proportion of Americans who are widowed has declined from 9% in 1960 to 6% in 2010 (Pew Research Center, 2011). In 2009, most spouses who experienced widowhood were over age 65 (70% among men and 66% among women). Over 70% experienced the death of their first spouse (i.e., were in a first marriage). Roughly 80% of recent widow(er)s are white and over half have no more than a high school diploma. Fewer than 7% are residing with their own minor children (Elliott and Simmons, 2011). Union formation following widowhood is more common among men than women and more likely to be marriage than cohabitation (Brown, Bulanda, and Lee, 2012).

Living Apart Together (LAT) describes long-term committed couple relationships that do not involve coresidence. Some couples are not able to live together because of geographical separation for work or school. Others prefer to maintain some autonomy and independence by living separately. It is difficult to obtain good estimates of the prevalence of LAT relationships in the United States since nearly all social surveys restrict their focus to household members. Nonetheless, a study using the General Social Survey suggests that roughly 7% of adults were involved in LAT relationships in the late 1990s, and more recent estimates from the state of California indicate about 12% of adults are in LAT relationships (Strohm et al., 2009). LATs are comparable to cohabitors in terms of average age (and younger than marrieds) but tend to be more highly educated than cohabitors. They are less likely than cohabitors to report plans to marry their current partner (Strohm et al., 2009). While LATs have received greater attention in the European context, there is increasing recognition that these relationships need to be integrated into our understanding of health and well-being of American adults.

Most adult Americans do not report a preference for sharing their home with their parents or adult children, even if there is an economic need (Seltzer, Bianchi, and Lau, 2012). Yet about 16.5% of households in 2000 and 17.7% in 2010 consisted of at least two generations of adults sharing a residence (Payne, 2012). There has been attention to the young adults who return home (boomerang children) (Newman, 2012). About half of young adults (18–24) lived with their parents in 2010 (53%) and in 2000 (52%) (US Census Bureau, 2012). A modest increase occurred among 25–34-year-olds from about 10% in 2000 to 14% in 2011 (Furstenberg, 2011; Jacobsen and Mather, 2011; Qian, 2012). The delay in marriage has provided more opportunities for returning home because unmarried young adults live with their parents more often than married young adults (Qian, 2012). The change in multigenerational living has not shifted much among older Americans in the last decade with nearly one-fifth living in multigeneration households. There may be growing parallels between American and European young adults who experience delays in independent living.

A group of Americans that has not received much attention is those who live alone. In 2000, 13% of adults lived alone, and today, about 14.3% live alone, which represents a historic high point since 1950 (Pew Research Center, 2010b). In terms of households, the levels have remained quite stagnant with about 25.8% of households in 2000 and 27.4% in 2010 composed of singles living alone (Lofquist et al., 2012). Klinenberg (2012) reports that Americans prefer to live alone but still value their social relationships and are not socially isolated. Among older Americans, there is remarkable stability in the proportion who live alone: 28.1% lived alone in 2000 and 27.4% did so in 2008 (Pew Research Center, 2010a). Further, much higher proportions of older women live alone (34%) than men (18%). As solo living increases, it may be more important to consider relationships that exist across household boundaries. For instance, the growing popularity of LAT relationships corresponds with the worldwide increase in solo living. At the same time, it is important to uncover the extent to which those living alone have access to social support, particularly with the aging of the population (Lin and Brown, 2012).

Our assessments of family change are often centered on the living arrangements of children because the family is the primary socializing unit and source of economic and emotional support for children. The initial living arrangements are measured at birth. In the last decade, the proportion of children born to unmarried mothers has increased from 33.2% in 2000 to 40.8% in 2010 (Martin et al., 2011). The current levels are at a historic peak. The share of births that are nonmarital doubled from 1980 when less than one-fifth (18.4%) of children were born to unmarried mothers (Martin et al., 2011). Driving this increase in nonmarital childbearing has been childbearing to cohabiting mothers. There has been a shift in the occurrence of nonmarital births to cohabiting women; in the late 1990s, about 40% compared with 58% in the early 2000s (Martinez, Daniels, and Chandra, 2012). Basically, there have been small declines in births to single mothers and married mothers with increases in children born to cohabiting mothers (Kennedy and Bumpass, 2011). This trend of most nonmarital births occurring to cohabiting mothers is similar to patterns in Europe.

Children’s family living arrangements at birth provide only a snapshot of their family experiences with many going on to experience parental (re)marriages, separations and divorce, and cohabitation. Estimates indicate that 24% of children experience the breakup of their parent’s marriage and two-thirds experience their cohabiting parent’s separation (Kennedy and Bumpass, 2011). About 50% of children born to unmarried mothers experience their mother’s marriage and nearly half (46%) their mother’s cohabitation (at birth or later) (Kennedy and Bumpass, 2011). As a result of all these family changes, the trends indicate a continual decline in children living in two biological married parent families. In 2001, 69.1% of children were living in two married biological parent families, while in 2010, 65.7% did so (US Bureau of the Census, 2011). The increasing complexity of family life from children’s perspectives requires assessments that account for this growing array of experiences, which have enduring consequences for child well-being (Brown, 2010).

Social class and family change

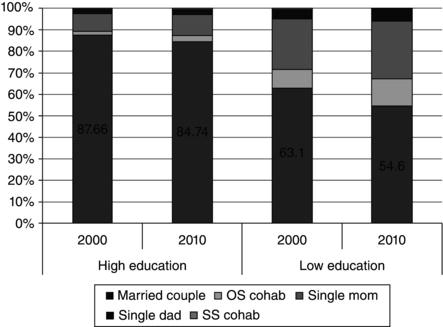

As socioeconomic inequality has risen in the United States, the divergence in family patterns has grown. A unique feature of American society is the vast divide in social class with a weak safety net for the disadvantaged. Several researchers have commented on how this growing income inequality has led to a divergence in American family patterns according to social class (Ellwood and Jencks, 2004; McLanahan and Percheski, 2008; Smock and Greenland, 2010; Cherlin, 2011). We draw on recent literature and reports on demographic trends along with our own analysis of Census and ACS data to track shifts in family patterns according to education level. For the purposes of this chapter, we consider educational attainment as a proxy for social class. We understand the concept of social class is complex and that a more nuanced portrait would include indicators of occupation, income, wealth, investments, and power. In the United States today, 15% of adults over age 25 have not graduated from high school, 29% only have a high school degree, 28% have some vocational education or some college, and 29% have a college degree or more (Julian and Kominski, 2011; Ryan and Siebens, 2012). Figure 3.1 shows the distribution of households with children according to family type for the most educated and least educated Americans. In 2000, we draw on Census data and in 2010 data from the American Community Survey. Among highly educated family households (the head and/or spouse/partner has a college degree) with children, the shift in family composition has been quite small with the vast majority (85%) of highly educated family households consisting of married couples. In contrast, there has been a decline among Americans with the lowest levels of education (the head and/or spouse/partner does not have a high school degree) in the proportion of family households with children that include married couples, from 63% in 2000 to 55% in 2010. Figure 3.1 shows that the education divide is apparent in 2000 and is becoming larger.

Figure 3.1 Family households with children: family structure and education of parents.

Source: Decennial Census (2000) and American Community Survey (2010): IPUMS.

Another lens on this question has been illustrated from the perspective of children. Elwood and Jencks (2004) discuss the education divide in family patterns and, in an analysis of Current Population Survey data, present the percentage of children living in single-mother homes over time and according to maternal educational attainment. An increase in children’s experience at time of interview in single-mother families occurred for children who have mothers with low levels of education, from about 30% in 1980 to 46% in 2010 (Elwood and Jencks, 2004; Author’s calculations CPS 2010). Children with mothers who were high school graduates or had some college education witnessed even sharper increases in single-motherhood experience. For example, 15% of children who have a mother with a high school degree lived in a single-mother home in 1980, and 40% did so in 2010. In contrast, about one-tenth of children who have mothers with college degrees have lived with a single mother, and this has remained stable over the last 30 years (Ellwood and Jencks, 2004; author’s calculations http://www.census.gov/hhes/families/data/cps2010.html Table C3).

The median age at entry into motherhood has increased; however, the increase has not been the same for all education levels. Prior work indicates that highly educated women are more likely to postpone or forego motherhood than their less educated counterparts (Abma and Martinez, 2006; Dye, 2010; England, McClintock, and Shafter, 2011). Recent analyses of the National Survey of Growth data indicate that in the late 1970s, the age at first motherhood for high school dropouts was 19.0, and in the late 2000s, it remained stable at 19.2 (Manning, Brown, and Payne, 2012). The age at motherhood for women with the highest levels of education has increased from 27.7 in the late 1970s to 29.9 in the late 2000s (Manning, Brown, and Payne, 2012). Highly educated women have fewer children on average and are more often childless (22%) than women who have not graduated from high school (15%) (Dye, 2010; Mosher, Jones, and Abma, 2012). Thus, the gap in the age at first motherhood has grown according to education. Highly educated women more often delay and are more often childless than their counterparts with lower levels of education.

As discussed earlier, the age at first marriage has increased, and these patterns differ according to education experience. In the late 1970s, there was a large education divide in the median age at first marriage, 19.1 among high school dropouts and 24.7 among college graduates (Manning, Brown, and Payne, 2012). The education gap in the median age at first marriage during the late 2000s is comparatively small, ranging from 24.3 among women without high school degrees to 26.8 among college graduates (Manning, Brown, and Payne, 2012). The proportion of 30–44-year-old women who ever married declined from 82% in 1970 to 69% in 2007 among college graduates, while during the same time frame, the proportion who ever married among those without a college degree declined from 83% to 56% (Fry and Cohn, 2010). In 2010, the marriage rate was over twice as high among college graduates as women with less than a high school degree (Payne and Gibbs, 2011). Thus, just as Goldstein and Kenney (2001) argued over 10 years ago, the marriage decline has occurred for all women, but it has been greater among those who have lower levels of education.

The divorce rate has remained relatively stable; however, there have been striking education differentials in divorce. The most educated appear to have experienced small gains in the stability of marriages (Martin, 2006; Amato, 2010; Copen et al., 2012). The education gap observed in the late 1980s has increased slightly today with a greater decline in divorce among college educated women than women without a high school degree (Raley and Bumpass, 2003; Martin, 2006; Isen and Stevenson, 2010; Copen et al., 2012). Drawing on 2006–2010 data, the probability a first marriage will disrupt by the tenth anniversary is lowest for college graduates (0.15) and graduate degrees (0.18), while the probability of disruption among women with only a high school degree or without a high school degree is 0.40 and with some college education is 0.37 (Copen et al., 2012). In contrast in the late 1980s, the probability of disruption within the first decade of marriage was 0.20 among college graduates and 0.39 among women without a high school degree (Raley and Bumpass, 2003). Based on 2010 data, the rate of divorce is lowest among college graduates and highest among women with some college education (Gibbs and Payne, 2011). The education gradient in divorce is not linear; women without a high school degree have divorce rates that fall between those with college degrees and those who have some post-high school educational attainment.

To understand the education gradient among women who have low levels of education requires acknowledging that foreign-born Latinas have the lowest educational attainment and relatively low dissolution rates. Assessments that exclude foreign-born Latinas indicate women without a high school degree have a much higher rate of dissolution than college graduates (Martin, 2006); however, inclusion of the foreign-born lowers the dissolution rates among women without a high school degree (Gibbs and Payne, 2011). Overall, the marriages of highly educated women are becoming more stable, while women who are less educated are experiencing rising disruption rates (Martin, 2006).

The result of the delays in marriage and almost no change in the age at parenthood has been growth in nonmarital childbearing. The education divide in premarital fertility has grown among more recent birth cohorts (England, Shafer, and Wu, 2012). Analyses of the National Survey of Family Growth indicate that in the late 2000s (2005–2010), 65% of all births to women with less than a high school degree were to unmarried women, and only 8% of births to college graduates were to unmarried women (Payne, Manning, and Brown, 2012). Most children born to college graduates accrue the benefits of parental marriage, while only one-third of children born to the least educated do so. Kennedy and Bumpass (2008) report that in the early 1990s, about half (52%) of births to women with less than a high school degree were to unmarried women, and only 5% of births to college graduates were to unmarried women. As Kennedy and Bumpass (2011) argue, most of the growth in unmarried motherhood is due to births to cohabiting women. The education gap in births to single mothers has remained constant, but the education gap in births to cohabiting mothers has grown. In the early 1990s, one-quarter (25%) of women with less than a high school degree had a birth while cohabiting, whereas in the late 2000s, 36% did so (Kennedy and Bumpass, 2008; Payne, Manning, and Brown, 2012). The shift in childbearing during cohabitation over the same time period among college graduates increased from 1% to 5%. The implications for child well-being are important to consider as children may benefit from the additional income and greater caretaking involvement that a second adult, cohabiting partner may provide.

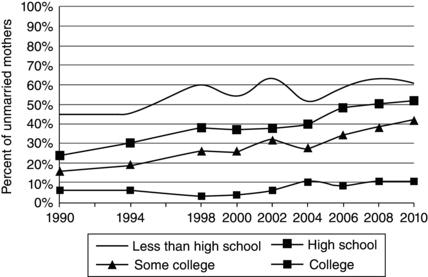

Another illustration of trends in nonmarital fertility according to educational attainment is based on our use of the Fertility Supplement of the Current Population Survey data. These data do not precisely measure the union status at time of birth but indicate whether a birth occurred in the last year and the union status at the time of interview. Figure 3.2 shows that the trend has been sustained high levels of unmarried motherhood among the least educated and sustained low levels among the most educated. High school graduates and women with some college have experienced sharp increases in unmarried motherhood. Taken together, these studies confirm that there has been a long-standing educational divide and the greatest growth in nonmarital fertility may be among the working class.

Figure 3.2 Percent of unmarried mothers.

Source: Data from Current Population Survey, June Fertility Supplements.

Cohabitation has increased more rapidly among those with lower levels of education. Twenty-five years ago, the education gap in cohabitation experience was relatively small (43% among those with less than 12 years of education versus 31% among college graduates) (Bumpass and Sweet, 1989). More recently, three-quarters of women with less than a high school degree had ever cohabited in contrast to half (47%) of college graduates (Manning, 2010). Cohabitation has increased for all women; however, it has become the overwhelming majority experience among the least educated and experienced by about half of college graduates today. In terms of trends in the type of first coresidential union formed, women who were working class (highest education was high school graduate or some college) experienced the greatest increase in cohabitation. In the mid-1980s, about half (56%) of high school graduates who formed a union first cohabited, while in the late 1990s, the vast majority (89%) did so (Manning, Brown, and Payne, 2012). Further, children’s experience in cohabiting-parent families has also increased such that in the late 2000s, about 70% of children with a mother with a high school degree or less lived in a cohabiting-parent family and only 10% of the children of college graduates did so (Kennedy and Bumpass, 2011). These findings illustrate that cohabitation has a different role in family formation according to social class. Cohabitation most often serves as a setting for childbearing and rearing among the less educated.

Although many young adults cohabit, others reside with their parents. Young adults are increasingly living with their parents across education groups with the greatest increase among 20–24-year-olds (Qian, 2012). Qian (2012) reports that over one-third of young adults in their early twenties with a high school degree (38%) or some college (37%) lived with their parents in 2000, and this increased to nearly half (45% and 46%, respectively) in 2007–2009. In 2000, 29% of college graduates lived with their parents, and in 2007–2009, 37% did so. The most disadvantaged young adults without a high school degree experienced only a modest change in parental coresidence, from 32% in 2000 to 35% in 2007–2009 (Qian, 2012). The working class appears to have experienced the greatest increase in parental coresidence. These findings suggest that parental coresidence is the result of economic need rather than personal preference. As young adults continue to suffer the aftereffects of the recent Great Recession, we can expect to see a rise in coresidence with parents as an economic survival strategy.

Conclusion

This chapter reviews the recent trends in family change in the United States and documents the dramatic shifts that have occurred in the last decade. A critical event shaping families over the last decade is the Great Recession that began at the end of 2007 and has played a large role in the shrinking of the middle class. For the first time in history, the middle class lost ground in recent years, leaving them with fewer resources to help weather further financial crises. The precarious status of the middle class may exacerbate the social class divide in family patterns in the near future. In fact, the recession may have added fuel to family trends that were already underway. The slow economic recovery means the lingering effects of the economic crisis persist today, affecting how Americans form and sustain families and contributing to even more pronounced diverging destinies for parents and their children (McLanahan, 2004). The hollowing out of the middle class will arguably contribute to the rise of fragile families, who are economically unstable, often unmarried families. At the other end of the spectrum, marriage may be more elusive for a growing share of Americans, reinforcing the notion that marriage is a luxury good or capstone event that is attainable only among the elite (Cherlin, 2004). This chapter has focused on how social class, operationalized by education, structures family life. We acknowledge that other indicators of social inequality such as race/ethnicity and nativity status as well as gender are also integral to family behaviors and experiences but maintain that education is a key marker of social status and is especially germane to understanding recent patterns and trends in US families.

The decline of marriage and rise of cohabitation are two of the most dramatic family changes in the last decade. Given economic stability is typically a prerequisite for marriage, it is not surprising that the age at marriage continues its steady ascent. The most educated have the oldest median age at first marriage; however, the education divide has narrowed with high school graduates often waiting as long as college graduates to get married, perhaps reflecting the growing propensity for disadvantaged young adults to substitute cohabitation for marriage. Delays in marriage may eventually lead to foregone marriage, especially for those who are disadvantaged economically.

At the same time, cohabitation is still on the rise, perhaps because it provides a way to form a joint household without the economic qualifications necessary for marriage. Most marriages are preceded by cohabitation, but this is much more common among women with only a high school degree (82%) than women with a college degree (59%). In other words, direct marriages (without cohabitation) occur primarily among the most educated. Further, serial cohabitation is increasing and is more common among those without college degrees. Thus, women who have lower levels of education have more complex relationship biographies than women who are more advantaged. In general, it seems cohabitation is less tied to marriage than it was a few decades ago as fewer cohabiting unions eventuate in marriage. We anticipate this trend will continue as cohabitation’s status as a family form becomes increasingly recognized and more widely shared (and marriage becomes out of reach for a growing share of Americans).

We highlight the growing diversity of family experiences. The legal recognition of same-sex marriage is spreading. At the same time, the legal and social recognition of other forms of relationships, for example, civil unions and domestic partnerships, is widespread and has implications for both same- and different-sex couples and parents. New relationship types have emerged, such as LAT, and may become entrenched as another form of intimate partnership. Intimate partnerships increasingly span household boundaries. New relationships may also extend across generations. Partly in response to the economic crisis, young adults who return to (or have never left) their parental home may need to forge new types of relationships with their parents. Additionally, older adults are likely to face challenges and opportunities as they draw on their more complex families for support in old age. One-third of Baby Boomers are unmarried and thus on the cusp of old age without a spouse available to provide care and support (Lin and Brown, 2012).

Children are now exposed to a wider array of family experiences that may include cohabiting and married stepparents, half-siblings, stepsiblings, and other relationships that we are less well able to label and identify. They also experience less stability in their families’ lives; family living arrangement transitions are increasingly common, even among young children. Living with two stable biological married parents remains on the horizon for the children of college graduates but has become a more elusive goal that is difficult for those with low education to attain.

One implication of these changes in the family landscape is a continued shift in expectations and attitudes toward varying family living circumstances. As children increasingly live in a wider range of families, their own family behaviors may be more diverse. Family change may operate as a feedback loop that generates further family change in the next generation.

A second implication of these trends concerns the health and well-being of children, adults, and families. The well-known advantages of married-couple families are not available to as many adults and children in 2010 as 2000. This is not to say that cohabiting, single-parent, and other types of families do not offer healthy home environments; rather, the legal and social protections that marriage affords children and parents are not an option for the majority. Many countries do not observe sharp differentials in the well-being of children according to family type because their children are buffered against disadvantage by universal and generous health and welfare benefits to all children. In the United States, it is possible that comparisons across family types may become less relevant as they are increasingly experienced by large and varied groups of children.

The landscape of US families continues to shift, and this transformation has been exacerbated by the recent economic crisis. Marriage is now just one of an array of options; families are increasingly formed outside the boundaries of marriage and often span across households. The declining centrality of marriage in the United States is fundamentally reshaping the family experiences of children and adults whose family life courses are increasingly variable and complex. Family change is especially pronounced among the most disadvantaged groups in the United States, and these patterns are likely to intensify as the sluggish economy continues to whittle away at the middle class. Our task as researchers is to document the trends and patterns characterizing US family life and link them to population health and well-being.

References

- Abma, J.C. and Martinez, G.M. (2006) Childlessness among older women the United States: trends and profiles. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 1045–1056.

- Amato, P.R. (2010) Research on divorce: continuing trends and new developments. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 650–666.

- Brown, S.L. (2010) Marriage and child well-being: research and policy perspectives. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 1059–1077.

- Brown, S.L. and Manning, W.D. (2009) Family boundary ambiguity and the measurement of family structure: the significance of cohabitation. Demography, 46 (1), 85–101.

- Brown, S.L. and Lin, I.-F. (2012) The gray divorce revolution: rising divorce among middle-aged and older adults, 1990–2010. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67, 731–741.

- Brown, S.L., Lee, G.R. and Bulanda, J.R. (2006) Cohabitation among older adults: a national portrait. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 61, S71–S79.

- Brown, S.L., Bulanda, J.R. and Lee, G.R. (2012) Transitions into and out of cohabitation in later life. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 774–793.

- Bumpass, L.L. and Sweet, JA. (1989) National estimates of cohabitation: cohort levels and union stability. Demography, 26, 615–625.

- Burgoyne, S. (2012) Demographic profile of same-sex parents. FP-12-15. National Center for Family & Marriage Research, http://ncfmr.bgsu.edu/pdf/family_profiles/file115683.pdf (accessed September 25, 2012).

- Cherlin, A.J. (2004) The deinstitutionalization of American marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 848–861.

- Cherlin, A.J. (2011) Between poor and prosperous: do the family patterns of moderately-educated Americans deserve a closer look? in Social Class and Changing Families in an Unequal America (eds. M.J. Carlson and P. England), Stanford University Press, Stanford, pp. 68–84.

- Cohen, J. and Manning, W.D. (2010) The relationship context of premarital serial cohabitation. Social Science Research, 39, 766–776.

- Copen, C.E., Daniels, K., Vespa, J. and Mosher, W.D. (2012) First marriages in the United States: data from the 2006–2010 national survey of family growth (number 40). Division of Vital Statistics, www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr049.pdf (accessed September 25, 2012).

- Cruz, J. (2012) Remarriage rate in the U.S., 2010. FP-12-14. National Center for Family & Marriage Research, http://ncfmr.bgsu.edu/pdf/family_profiles/file114853.pdf (accessed September 25, 2012).

- Dye, J.L. (2010) Fertility of American women: 2008. Current population reports (20–536), www.census.gov/prod/2010pubs/p20-563.pdf (accessed September 25, 2012).

- Elliott, D.B. and Simmons, T. (2011) Marital events of Americans: 2009. American Community Survey, http://www.census.gov/prod/2011pubs/acs-13.pdf (accessed September 25, 2012).

- Elliott, D.B., Krivickas, K., Brault, M.W. and Kreider, R.M. (2012) Historical marriage trends from 1890–2010: a focus on race differences. Presented at the Annual Meetings of the Population Association of America, San Francisco.

- Ellwood, D.T. and Jencks, C. (2004) The uneven spread of single-parent families: what do we know? in Social Inequality (ed. K.M. Neckerman), Russell Sage Foundation, New York, pp. 3–78.

- England, P., McClintock, E.A. and Shafer, E.F. (2011) Birth control use and early, unintended births: evidence for a class gradient, in Social Class and Changing Families in an Unequal America (eds. M.J. Carlson and P. England), Stanford University Press, Stanford.

- England, P., Shafer, E.F. and Wu, L.L. (2012) Premarital conceptions, postconception (“shotgun”) marriages, and premarital first births: education gradients in U.S. cohorts of white and black women born 1925–1959. Demographic Research, 27 (6), 153–166.

- Fry, R. and Cohn, D. (2010) Women, men and the new economics of marriage. Pew Research Center Social and Demographic Trends, http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/files/2010/10/new-economics-of-marriage.pdf (accessed September 25, 2012).

- Furstenberg, F.F., Jr. (1987) The new extended family: the experience of parents and children after remarriage, in Remarriage and Step-Parenting: Current Research and Theory (eds. K. Pasley and M. Ihinger-Tallman), Guilford, New York.

- Furstenberg, F.F., Jr. (2011) The recent transformation of the American family: witnessing and exploring social change, in Social Class and Changing Families in an Unequal America (eds. M.J. Carlson and P. England), Stanford University Press, Stanford, pp. 192–220.

- Gates, G.J. (2012) Same-sex couples in census 2010: race and ethnicity. The Williams Institute, http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Gates-CouplesRaceEthnicity-April-2012.pdf (accessed September 25, 2012).

- Gerson, K. (2000) Resolving family dilemmas and conflicts: beyond utopia. Contemporary Sociology, 29 (1), 180–188.

- Gibbs, L. and Payne, K.K. (2011) First divorce rate, 2010. FP-11-09. National Center for Family & Marriage Research, http://ncfmr.bgsu.edu/pdf/family_profiles/file101821.pdf (accessed September 25, 2012).

- Goldstein, J.R. and Kenney, C.T. (2001) Marriage delayed or marriage forgone? New cohort forecasts of first marriage for U.S. women. American Sociological Review, 66 (4), 506–519.

- Isen, A. and Stevenson, B. (2010) Women’s education and family behavior: trends in marriage, divorce and fertility. Cambridge, MA. NBER working paper no. 15725.

- Jacobsen, L.A. and Mather, M. (2011) Population bulletin update: a post-recession update on U.S. social and economic trends, www.prb.org/pdf11/us-economic-social-trends-update-2011.pdf (accessed September 25, 2012).

- Julian, T. and Kominski, R. (2011) Education and synthetic work-life earnings estimates. American Community Survey Reports, www.census.gov/prod/2011pubs/acs-14.pdf (accessed September 25, 2012).

- Kelly, J.B. (2007) Children’s living arrangements following separation and divorce: insights from empirical and clinical research. Family Process, 46, 35–52.

- Kennedy, S. and Bumpass, L.L. (2008) Cohabitation and children’s living arrangements: new estimates from the United States. Demographic Research, 19, 1663–1692.

- Kennedy, S. and Bumpass, L.L. (2011) Cohabitation and trends in the structure and stability of children’s family lives. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America, New Orleans, April 1, 2011.

- King, V. and Scott, M.E. (2005) A comparison of cohabiting relationships among older and younger adults. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 271–285.

- Klinenberg, E. (2012) Going Solo: The Extraordinary Rise and Surprising Appeal of Living Alone, Penguin Books, New York.

- Kreider, R.M. and Ellis, R. (2011) Number, Timing, and Duration of Marriages and Divorces: 2009. Current population reports, pp. 70–125, www.census.gov/prod/2011pubs/p70-125.pdf (accessed September 25, 2012).

- Lichter, D.T., Turner, R.N. and Sassler, S. (2010) National estimates of the rise in serial cohabitation. Social Science Research, 39, 754–765.

- Lin, I.-F. and Brown, S.L. (2012) Unmarried boomers confront old age: a national portrait. The Gerontologist, 52, 153–165.

- Lofquist, D., Lugaila, T., O’Connell, M. and Feliz, S. (2012) Households and Families 2010. U.S. Census Bureau, http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-14.pdf (accessed September 25, 2012).

- Manning, W.D. (2010) Trends in cohabitation: twenty years of change, 1987–2008. FP-10-07. National Center for Family & Marriage Research, http://ncfmr.bgsu.edu/pdf/family_profiles/file87411.pdf (accessed September 25, 2012).

- Manning, W.D., Smock, P.J. and Majumdar, D. (2004) The relative stability of marital and cohabiting unions for children. Population Research and Policy Review, 23, 135–159.

- Manning, W.D., Brown, S.L. and Payne, K.K. (2012) Stability and change in age at first union formation over the last two decades: a research note. Working paper. National Center for Family & Marriage Research Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, Ohio.

- Martin, M.A. (2006) Family structure and income inequality in families with children: 1976 to 2000. Demography, 43, 421–445.

- Martin, J.A., Hamilton, B.E., Ventura, S.J. et al. (2011) Births: final data for 2010. National Vital Statistics Reports, 61, 1, www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr61/nvsr61_01.pdf (accessed September 25, 2012).

- Martinez Gladys, D., Daniels, K. and Chandra, A. (2012) Fertility of men and women aged 15–44 years in the United States: national survey of family growth, 2006–2010. National Health Statistics Reports, 51, www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr051.pdf (accessed September 25, 2012).

- McLanahan, S.S. (2004) Diverging destinies: how children are faring under the second demographic transition. Demography, 41, 607–627.

- McLanahan, S.S. and Percheski, C. (2008) Family structure and the reproduction of inequalities. Annual Review of Sociology, 34, 257–276.

- McNamee, C.B. and Raley, R.K. (2011) A note on race, ethnicity and nativity differentials in remarriage in the United States. Demographic Research, 24 (13), 293–312.

- Mosher, W.D., Jones, J. and Abma, J.C. (2012) Intended and unintended births in the United States: 1982–2010. National Health Statistics Report, 55, 1–28.

- National Center for Family & Marriage Research (2012) Counting Couples, Counting Families: Full Report, Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, http://ncfmr.bgsu.edu/pdf/Counting%20Couples/file115721.pdf (accessed September 25, 2012).

- Newman, K.S. (2012) The Accordion Family: Boomerang Kids, Anxious Parents, and the Private Toll of Global Competition, Beacon Press, Boston.

- Pasley, K. (1987) Family boundary ambiguity: perceptions of adult stepfamily members, in Remarriage and Stepparenting: Current Research and Theory (eds. K. Pasley and M. Ihinger-Tallman), Guilford, New York, pp. 206–224.

- Payne, K.K. (2012a) Median age at first marriage, 2010. FP-12-07. National Center for Family & Marriage Research, http://ncfmr.bgsu.edu/pdf/family_profiles/file109824.pdf (accessed September 25, 2012).

- Payne, K.K. (2012b) Young adults in the parental home, 1940–2010. FP-12-22. National Center for Family & Marriage Research, http://ncfmr.bgsu.edu/pdf/family_profiles/file122548.pdf (accessed September 25, 2012).

- Payne, K.K. and Gibbs, L. (2011) First marriage rate in the U.S., 2010. FP-11-12. National Center for Family & Marriage Research, http://ncfmr.bgsu.edu/pdf/family_profiles/file104173.pdf (accessed September 25, 2012).

- Payne, K.K., Manning, W.D. and Brown, S.L. (2012) Unmarried births to cohabiting and single mothers, 2005–2010. FP-12-06. National Center for Family & Marriage Research, http://ncfmr.bgsu.edu/pdf/family_profiles/file109171.pdf (accessed September 25, 2012).

- Pew Research Center (2010a) Pew research center tabulations of the decennial U.S. census data, 1950–2000, and current population survey, annual social and economic supplement, 2001–2009, http://pewsocialtrends.org/files/2010/10/752-multi-generational-families.pdf (accessed September 25, 2012).

- Pew Research Center (2010b) The Return of the Multi-Generational Family Household. http://pewsocialtrends.org/files/2010/10/752-multi-generational-families.pdf (accessed September 25, 2012).

- Pew Research Center (2011) New Marriages Down 5% from 2009 to 2010: Barely Half of U.S. Adults Are Married – A Record Low, http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2011/12/14/barely-half-of-u-s-adults-are-married-a-record-low/?src=prc-headline (accessed September 25, 2012).

- Pew Research Center (2012a) Fewer, Poorer, Gloomier: The Lost Decade of the Middle Class, http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2012/08/22/the-lost-decade-of-the-middle-class/ (accessed September 25, 2012).

- Pew Research Center (2012b) Two-Thirds of Democrats Now Support Gay Marriage. http://www.pewforum.org/Politics-and-Elections/2012-opinions-on-for-gay-marriage-unchanged-after-obamas-announcement.aspx (accessed September 25, 2012).

- Pizer, J.C. and Kuehl, S.J. (2012). Same-Sex Couples and Marriage: Model Legislation for Allowing Same-Sex Couples to Marry or All Couples to Form a Civil Union. The Williams Institute, http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Pizer-Kuehl-Model-Marriage-Report.pdf (accessed September 25, 2012).

- Powell, B., Steelman, L.C. and Pizmony-Levy, O. (2012) Transformation or continuity in Americans’ definition of family: a research note. Bowling Green State University NCFMR working-paper 12–12. http://ncfmr.bgsu.edu/pdf/Brian%20Powell%202012/file119560.pdf (accessed October 31, 2013).

- Powell, B., Bolzendahl, C., Geist, C. and Carr Steelman, L. (2010) Counted Out: Same Sex Relations and Americans’ Definition of Family. Russell Sage Foundation, New York.

- Qian, Z. (2012) During the great recession, more young adults lived with parents. Census brief prepared for project US 2010, http://www.s4.brown.edu/us2010/Data/Report/report08012012.pdf (September 25, 2012).

- Raley, R.K. and Bumpass, L.L. (2003) The topography of the divorce plateau: levels and trends in union stability in the United States after 1980. Demographic Research, 8, 245–259.

- Ryan, C.L. and Siebens, J. (2012) Educational Attainment in the United States: 2009, Population Characteristics, www.census.gov/prod/2012pubs/p20–566.pdf (accessed September 25, 2012).

- Schoen, R. and Standish, N. (2001) The retrenchment of marriage: results from marital life tables for the united states, 1995. Population and Development Review, 27, 553–563.

- Seltzer, J.A., Lau, C.Q. and Bianchi, S.M. (2012) Doubling up when times are tough: a study of obligations to share a home in response to economic hardship. Social Science Research, 41 (5), 1307–1319.

- Smock, P.J. and Greenland, F.R. (2010) Diversity in pathways to parenthood in the U.S.: patterns, implications, and emerging research directions. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72 (3), 576–593.

- Stevenson, B. and Wolfers, J. (2007) Marriage and divorce: changes and their driving forces. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21 (2), 27–52.

- Strohm, C.Q., Seltzer, J.A., Cochran, S.D. and Mays, V.M. (2009) Living apart together relationships in the United States. Demographic Research, 21, 177–214.

- Sweeney, M.M. (2010) Remarriage and stepfamilies: strategic sites for family scholarship in the 21st century. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 667–684.

- Teachman, J. (2008) Complex life course patterns and the risk of divorce in second marriages. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70, 294–305.

- U.S. Census Bureau (2011) U.S. Census Bureau CPS, Families and Living Arrangements: 2010, http://www.census.gov/hhes/families/data/cps2010.html (accessed September 25, 2012).

- U.S. Census Bureau (2012) U.S. Census Bureau CPS, Families and Living Arrangements: 2011, http://www.census.gov/hhes/families/data/adults.html (accessed September 25, 2012).

- White, L.K. (1998) Who’s counting? Quasi-facts and stepfamilies in reports of number of siblings. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 60, 725–733.