5

Changes and Inequalities in Latin American Families

Irma Arriagada

Introduction

To understand the changes in families in Latin America, this chapter adopts a gender-based perspective: while the family is analyzed as a field for the exercise of personal rights, individual family members interact with unequal and asymmetric power within it. Gender processes in Latin America reflect both the legacy of the Creole family system (described by Therborn, Chapter 1) and the transformations brought about by economic modernization and by new ways of thinking and acting associated with modernity. Typical of Latin American societies is a high degree of exclusion and poverty, which results in basic inequality in living conditions and in exposure to the region’s integration into the global economy and culture. As a result, new combinations of gender inequality, family life cycles, and income are emerging, together with the new paradoxes that families display in the context of modernity and modernization tempered by exclusion.

This analysis draws on earlier work (Arriagada, 1998, 2002, 2007, 2012), which is updated for this volume. Because Latin American family trends may be less familiar to readers of this Companion, this diagnosis draws on data sources from the 1990 and 2009 household surveys, which have been processed by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC, http://www.eclac.org) to make them comparable to one another. They correspond to the Latin American urban population (80.9%) (ECLAC, 2011b). As these consider only two recent points in time, they cannot be used to analyze the long-term evolution of the Latin American family. Accordingly, this paper makes only a cautious analysis of aspects derived from the data used, supplementing conclusions with other sources including studies that illustrate aspects that have not been investigated in surveys of internal family organization, together with references of a more historical nature. For a recent review on Latin American families with a particular emphasis on policy, see García and de Oliveira (2011).

Family studies: Main paradigms

The classic paradigms of sociological studies have stressed the family’s central role in the functioning of society – either invoking a structural-functionalist tradition that relates family matters to the stability of institutions and ultimately society itself or a Marxist perspective that perceives close links between changes in the family and developments in other social institutions such as private property, social class, industrial society, and the State. The link between family change and modernization processes was thus recognized early in sociological analysis, in terms of the development of the nuclear family and individual income. Nonetheless, the associated concept of the patriarchal family was not addressed in depth in the leading theories on the family in vogue at the time, especially those in the North American structural-functionalist tradition.

More recently, and from the very start of gender studies, a more critical view has been taken of the asymmetries that exist among family members in terms of power, resources, and negotiating capacity. In this respect, the greatest power is generally associated with whoever generates the family’s monetary income, or the person that cultural norms expect to do so – usually the male head of household. Attention has also been drawn to the way the distribution of resources, power, and time affects women’s differential participation in the labor market, politics, and public life generally. The inequality among family members with different degrees of power on account of their sex and age has also been highlighted, thereby demonstrating the persistence of gender asymmetries.

The twentieth-century patriarchal family makes a clear distinction between the public and private domains, with a sharp division of labor between men and women. The man is responsible for establishing a family, based on very clear structural relations of authority and affection toward his wife and children, which are legitimized in the outside world and enable him to provide for, protect, and guide his family. Women, on the other hand, are expected to complement and collaborate with the husband/father (Olavarría and Parrini, 2000). In most Latin American countries, the law reflects this traditional family model, which displays a strong resistance to change. Nonetheless, there have been a number of positive changes, such as the Responsible Parenthood Act recently passed in Costa Rica and legislation against domestic violence passed in most countries of the region.

In Latin America, family formations in the Creole society were profoundly marked by the patriarchal Spanish colonial legacy and by a population model of informal constitution of couples that implied extramarital births and a socially accepted practice of male sexual predation (Therborn, 2007). The gender system in urban mestizo societies attached great importance to the separation between the public and the domestic domains, control of female sexuality, the concept of family honor, recognition by other men, and fatherhood as a means of asserting one’s masculinity. Historically, class and ethnic differences intensified control over women’s sexuality, allowing men the possibility of having relationships with women from different social groups according to different rationales and moral codes. On the other hand, the fragile nature of public institutions in those societies led to the domestic/public contrast being perceived in territorial terms: in the home or on the street. While the home is an ordered space where kinship relations and personal networks unfold, the street is an ambiguous space where personal desires override the common interest (Fuller, 1997; Ariza and de Oliveira, 2004). This patriarchal model of the family is currently being questioned in both public and private, and there is a striking variety in people’s representations, discourses, and practices.

Thus, modern family studies see the interaction among gender, social classes, and ethnic groups as central pillars of inequality that define very different conditions of life and structures of opportunities while looking closely at the interrelations among individual time frames, family cycles, and social processes.

Modernity and Modernization in Latin America

The changes that have occurred in the family in relation to the incorporation of Latin America to a global economy and to processes of modernization and modernity are relatively unknown. These transformations arise from sociodemographic transitions, the upheavals of economic crises and their social repercussions, as well as changes in the cultural ambit and in the representations and aspirations in relation to the family.

Modernization and modernity with exclusion

In Latin American countries and elsewhere, a widely debated and recurring theme in sociology concerns modernization and the social and economic processes that accompany it. The consideration of modernity, in contrast, mainly focuses on normative aspects, cultural dimensions, and acceptance of the diversity of identities in pluralistic societies. In general, these two processes have not evolved in the same direction. The relation between the processes of subjectivization (as a perception of this process by individuals, characteristic of modernity) and modernization has proven to be unpredictable, asynchronous, and at times contradictory (Wagner, 1994; UNDP, 1998).

The distinguishing aspects of modernity include the changes that have occurred within the family and the dimensions most closely related to social identity processes that tend to generate increasing autonomy – especially the changing social roles of women.

The distinction between the processes of modernization and modernity is analytical, for the two concepts are closely interrelated (Calderón, Hopenhayn, and Ottone, 1993). Some dimensions are shared – for example, the progressive secularization of collective action, which began with the separation of powers between the State and the Church, but later, in the case of the family, involved recognition of the right to divorce, which is no longer condemned by religious authorities but seen as a “reflexive” personal choice.

Modernization processes and their effects on families include the following:

- Changes in production processes: These include economic growth generated by industrialization, by the transition from rural to urban work, and, today, by the development of preeminently market-based global service economies.

- Changes in demographic structure: Rapid urbanization processes, longer life expectancy, lower birthrates, and shrinking family size, reflected in changes in the population-age pyramid and family structure.

- New patterns of work and consumption: Families have increasing access to goods and services, and there are changes in the forms of work – expansion of the industrial and service sectors, of paid female work, of informal-sector employment, and of job instability.

- Massive but segmented access to social goods and services such as education, social security, and healthcare: The coverage of the services is expanded, but there is also greater social fragmentation and inequality due to the different qualities of services supplied.

These changes in basic living conditions caused by the large-scale processes related to globalization and modernization – especially urbanization associated with industrialization, the growth of female employment, new consumption patterns, and new forms of labor market participation – have a key influence on the organization of families and the way they perceive themselves.

With regard to modernity, other aspects are taken into account, such as the following:

- Promotion of social and individual freedom (individualization): This involves expansion of the rights of women and children; questioning of the patriarchal system within the family; profound changes in the areas of intimacy and sexuality; and a search for new identities (Giddens, 1992). The thesis of individualization for analyzing the family, however, has been questioned even in developed countries (Smart and Shipman, 2004).

- Progress of the social dimension in the development of individual potential: This development is to the detriment of the importance accorded to the family.

- Progressive secularization of collective action: As more and more people distance themselves from religion-based codes of behavior, individual ethics are gaining force, especially with regard to the exercise of reproductive rights and sexual morality.

- Spread of a formal and instrumental logic: The emphasis on reasoning that is rational and calculated in pursuit of goals.

- Reflexivity: This refers to the fact that most aspects of social activity are continuously being reassessed in the light of new information or knowledge (Giddens, 1990). The family is not exempt from this reflexive approach, which changes people’s courses of action and is particularly striking in the case of women (specifically in the feminist movement), representing the point at which male domination breaks down (Bourdieu, 2001).

- The spread of democratic attitudes: Defense of diversity and increased tolerance; broadening of citizenship to include other social sectors such as ethnic groups, women, young people, and children.

- Democratic representation in government: Marked by the presence of different social attitudes and values.

- Generation of increasingly multicultural societies: Embracing diversity in lifestyles and family forms and structures.

In brief, modernity in the family is likely to be reflected in the exercise of democratic rights and autonomy among family members, together with a fairer distribution of labor (domestic and social), opportunities, and family decision making. This implies a new relationship based on asymmetries tempered by democratic principles (Salles and Tuirán, 1996).

Some elements of modernization processes in Latin America have not developed fully, resulting in small groups being included in social and material benefits while large population sectors are left out. Many of the changes associated with modernization have been carried out in a segmented way without being accompanied by the processes characteristic of modernity, especially as regards the cultural and identity dimensions of those changes.

Modernity is essentially a posttraditional order, characterized by increasing diversity of lifestyles and modes of living, with heterogeneous influences affecting habits, values, images, and modes of thought and entertainment. This is boosted by globalization processes that have affected the social links among groups and have had powerful effects on the more personal aspects of our experience, where the security that traditions and customs used to provide has not been replaced by the certainty of rational knowledge (Giddens, 1991). Accordingly, the changes in the family caused by the processes of modernization and modernity become a breaking point in the private–public dichotomy and give rise to emerging forms of family life that redefine the relationship between the family and society. In the case of Latin America, this is accompanied by a process of hybridization to the extent that very traditional and patriarchal forms of the family persist alongside of new styles of family life. These styles overlap strongly with ethnic–racial identity and social class, which define not only material conditions of life but also symbolic forms and very different family values.

The present Latin American context and its impact on families

Socioeconomic changes

From an economic, social, and cultural standpoint, there are a number of worrying aspects in the structural situation of Latin America. Though there have been economic growth and increasing job opportunities during the last years, there have also been persistent informal employment and regressive income distribution that affect families differentially. The continuing process of neoliberalism that includes privatization of education, health, and social security requires more economic resources from families to cover their needs.

Social security coverage, for example, continues to be low; only 43% of households have at least one member affiliated with a social insurance system and in only 32% of households is the head of the household or spouse affiliated. Gender and generational gaps are evident, given that the level of social security coverage is significantly higher among households with a male head (49.5%) than households with a female head (41.3%). Likewise, young people have lower levels of coverage than adults (ECLAC, 2011a).

Alongside these processes, the expansion of the working-age population has generated simultaneous trends toward precarious employment and unemployment in the region. Unemployment is higher among the poorer segments, those with less education, young people, and women. Another worrying aspect is the contradiction between the increase in structural unemployment1 and economic growth, with all the damage that this causes to family security and stability.

Recent trends also reveal the deteriorating situation, impoverishment, and indebtedness of middle-income groups. More and more family members (especially women, young people, and children) are finding work in traditionally precarious and low-productivity sectors. The entry of women into low-paid jobs offers them limited chance of improving their employment prospects. While paid employment is a way of enhancing their living standards and gaining greater self-sufficiency, it has the disadvantage that it further increases the total workload borne by women. They have to divide their responsibilities between the family and their job while receiving little support from their partner or from social institutions. This is particularly true of poorer women. Mothers with higher incomes can hire domestic workers for their homes or private services to take care of their children.

In addition to these aspects, there has been a revolution in expectations, fueled by the mass media. This has increased the sense of frustration at the widening gap between the growing desire for consumption and the real possibility of obtaining desired goods. Inequality in the region is growing and income differences are widening, which severely hinders the possibilities of the social integration of marginalized families into society and further aggravates the sources of differences among them.

Demographic changes

Alongside with the modernization process, there is massive access to modern contraceptive methods – derived from the first demographic transition, which involved a reduction in mortality and fertility rates and an increase in life expectancy. This transition has had major effects on Latin American families. Longer life expectancy has lengthened the duration of life as a couple. In Mexico, it is estimated that husband/wife roles can span up to 40 years of people’s lives (Ariza and de Oliveira, 2001). In countries such as Argentina, Uruguay, and Chile, the period could be even longer, barring separation or divorce. Also, there are increasing numbers of single-person households, families made up of older adults, and households with no children. At present, one in every four Latin American households contains at least one older adult (ECLAC, 2000a). This increase in the number of older persons means an increase in the caregiving work performed by women in their homes.

Average family size has shrunk because couples are having fewer children and births are being spaced more widely apart. The number of multigenerational families is falling, while single-person households are on the rise. Migration, which may occur for a variety of reasons (economic considerations, armed conflict, and domestic violence, among others), is another factor leading to smaller households.

Fertility rates had fallen in most Latin American countries. The average Latin American Total Fertility Rate (TFR) was 5.9 children per woman in the 1950s, declined to 2.3 by the 2005–2010 period when the rate for Europe was 1.4 and 2.0 for the United States (ECLAC, 2007). Today, the Latin American rates are below the world average of 2.5 children per woman and similar to levels observed in Europe 40 years ago. Some countries already have fertility rates below replacement level. Recently, however, they have stabilized, and in some cases (Argentina, Chile, Panama, and Uruguay), there has been an increase in adolescent fertility rates, which reflects the fact that different countries are at different stages in the demographic transition.

The highest adolescent fertility rates are in the poorest population groups, among teenagers with little schooling, in rural areas, and in areas with high concentrations of indigenous people (ECLAC, 2000b; Guzmán, Hakker, and Contreras, 2001; ECLAC, 2011a). The factors that have contributed the most to the drop in fertility are associated with exposure to sexual relations, such as not entering a union or doing so later in life, or separating from a partner either temporarily or permanently. These account for nearly 50% of the decline compared to natural fertility. The use of contraceptives accounts for more than 40% of the decline (ECLAC, 2011a).

In some of the region’s socially more developed countries (such as Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay), the models of sexual, marital, and reproductive behavior that are widespread in developed countries are beginning to take root among higher-income and more educated social groups. These include later marriage and reproduction among young people with high levels of schooling. In Chile, for example, the male age at marriage rose from 26.6 to 29.4 years between 1980 and 1999; the female age rose from 23.8 to 26.7. There were higher rates of divorce and cohabitation among Latin America’s middle-income groups. In Chile, the number of divorces in 2009 (50,269) was almost equal to the number of marriages (52,834). The number of marriages decreased, the number of annulments increased, birthrates diminished, and the number of children born outside marriage increased. In 1999, 47.7% of Chilean children were nonmarital births, whereas the 1990 figure had been only 34.3%. The consolidation of similar patterns in Europe led some to suggest that they represent a second demographic transition.

This second transition is associated with a profound change in values, closely related to Giddens’s concept of late modernity (Giddens, 1990, 1992). Demographers studying this subject have preferred to associate it with “postmaterialist values” (Inglehart, cited by Van de Kaa, 2001) and, more recently, with postmodernization and postmodernity (Van de Kaa, 2001). Apart from fertility indices that are well below replacement levels, this second transition includes the following features: (i) an increase in celibacy and voluntarily childless couples; (ii) postponement of first union; (iii) later birth of the first child; (iv) consensual unions increasingly seen as an alternative to marriage; (v) an increase in the number of children born and raised out of wedlock; (vi) greater frequency of marital breakdown (divorce); and (vii) diversification of family structures.

Some of these features have a long history in Latin America, and their existence has less to do with modernity than with socioeconomic exclusion and poverty and even with traditionalism. This is true of both consensual unions and marital abandonment, historically documented in the concept of the huacho, which refers to the child without a present or known father and born out of wedlock (also denominated “illegitimate”). In short, certain sociodemographic phenomena affecting Latin American families conceal differentiated and specific determinants, directions, and consequences that depend on the socioeconomic group in which they occur. Cohabitation, which is emerging as a modern lifestyle among the middle class today, long existed as a traditional pattern among poor segments of the population.

It has been asserted that all three dimensions of the classic definition of the family – sexuality, procreation, and cohabitation – have changed profoundly and have begun to evolve in different directions, resulting in a growing multiplicity of family and cohabitation models (Jelin, 1998). It is generally agreed that most of the changes in family structure are gradual and are influenced by family location (urban vs. rural), social class, and the various experiences that Latin American societies have gone through (Salles and Tuirán, 1997). Other changes have been very dynamic, however, including the extremely rapid evolution of the social roles of women both within and outside the family, the increase in their labor market participation, and the growing number of households headed by women.

The Main Changes in Latin American Families

In recent decades, different processes have produced changes in the structure and behavior of families in Latin America. From the economic point of view, the incorporation of Latin America into the global economy has modified forms of work and employment, which in turn have affected the organization and distribution of rights and responsibilities within the family. The demographic changes related to reduced fertility, increased life expectancy, and migration are also affecting family size and structure. The entry of women into the labor market triggered a cultural and subjective transformation that has been termed the “quiet revolution” (Goldin, 2006; Esping-Andersen, 2009) because of its scope. All these transformations have been marked by major cultural changes about the value of the family, acceptance of new forms of family structure, and increasing possibilities of choice, especially for women. As Jelin (1998) indicated, transformations in family formation, dynamics, and structure express the diffusion and adoption of new values related to a process of autonomy and a demand for individual interests and rights, in particular in gender and intergenerational relationships, that is, values linked to modernity.

New family structures: Type and family cycle

Analyses based on ECLAC data from 1990 and 2009 show significant changes in Latin American families in recent decades. The main transformations in family structures are synthesized in the following based on information from household surveys in urban areas in 18 Latin American countries.

Diversification of family types: Families and households moved away from the dominant two-parent-with-children model between 1990 and 2009. A family and household typology for family and nonfamily household types was constructed to analyze this diversification and is presented in Box 5.1.

The most important model in urban Latin America is the nuclear family, that is, the two-parent family with children. It decreased from 46.3% in 1990 to 41.1% in 2005. In 2005, this nuclear family coexisted with the extended family, usually with three generations, which represented slightly more than a fifth of all Latin American families (21.7%).

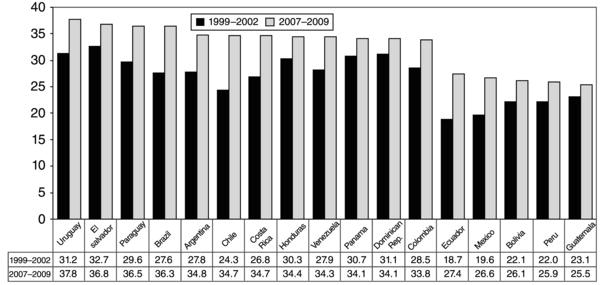

Another tendency, the increase in families with a female head, has acquired visibility and been analyzed extensively in the Latin American region, especially in Central America (López and Salles, 2000; ECLAC, 2004). The percent of households headed by women increased in each of 17 Latin American countries between about 1999 and 2009 (Figure 5.1). From a demographic perspective, female headship is related to the increase in singleness, resulting from separations and divorces, from migration, and from extended widowhood, which reflects the increase in female life expectancy. From a socioeconomic and cultural perspective, this growth in female headship relates to women’s increased levels of education and their growing economic participation, which allows them the economic independence and social autonomy to establish or continue households without partners. Women head almost a third of families in Latin America. In 2009, the lowest percentage was in Guatemala (25.5%), and the highest was in Uruguay (37.8%) (see Figure 5.1). The percentage of indigent households headed by women is higher than the average, reflecting the facts that such households tend to have more dependents, women’s earnings in the labor market are lower, and obligations of childcare limit their possibilities in choosing employment.

Figure 5.1 Percentage of female headed households by country: 17 Latin American countries: 1999–2002 and 2007–2009.

Source: ECLAC (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean) (2010b) Social Panorama of Latin America 2010 (LC/G.2481-P), March 2011, Santiago, Chile. United Nations Publication, Sales No. E.11.II.G.6.

Between 1990 and 2005, there has also been an increase in nonfamily households, among which one-person households have increased the most (6.7%–9.7%). The individualization that forms part of modernity is reflected in the increase in one-person households, that is, households of persons who opt not to live in a family. They are most commonly young people who postpone matrimony or cohabiting. Likewise, the aging of the Latin American population partly accounts for the increase in one-person households among elderly persons (especially widows due to their longer life expectancy) with sufficient resources to live apart from kin.

In effect, there are a wide variety of family arrangements today. Adults can opt to live alone, in a couple without children, in one-parent households, in consensual unions, in same-sex (gay or lesbian) unions, and so on. There are a growing number of blended families (couples who bring together their children by another partner from previous unions), as well as distant families as products of the migration of family members. However, the weight of many of these changes is unknown because their magnitude cannot be inferred based on information from household surveys. Case studies, however, show important changes in the perception of who are members of such families, greater individualization of the members of the family, and acceptance of distinct affective logics by members within the same family (Wainerman, 2005; Araujo and Martuccelli, 2012).

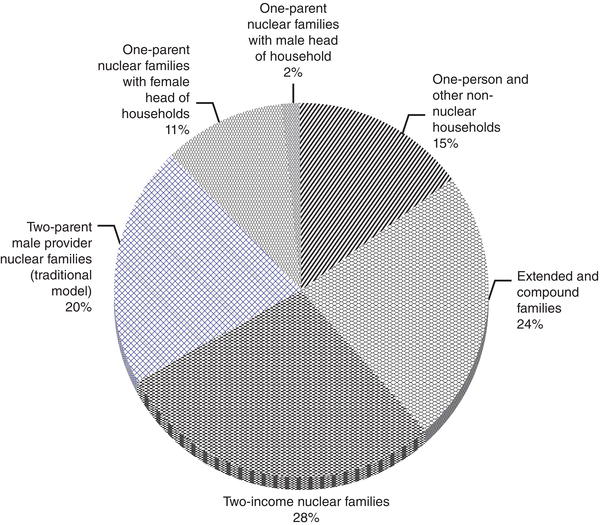

Decline in the male-provider family model: This male-provider model corresponds to the traditional concept of the nuclear family, in which both parents are present along with their children, the mother works as a housewife full time, and the father acts as the only breadwinner. Increased educational levels and the growing economic incorporation of women have led to a shift from the “male-provider” model to that of the “double-income family.” The labor force participation rate of urban women in Latin America in 1990 was 42% and by 2010 increased to 52% (ECLAC, 2012). In effect, in the majority of Latin American families, women have ceased to be exclusively housewives and have entered the labor market, making an important new contribution to family income. This is reflected in the trend to a lower percentage of nuclear families in which there are children and the female spouse does not work (from 47.6% in 1990 to 30.2% in 2009); there is a higher percentage in which the female spouse does combine work and children (from 26.7% in 1990 to 33.5% in 2009). Figure 5.2 shows the situation in 2005. The most traditional model of the nuclear family, with two parents, children, and a female spouse who dedicates herself to domestic work (male-breadwinner model), represented one in five (20.9%) urban Latin American households.

Figure 5.2 Percent distribution of urban families and households, by type and country: 18 Latin America countries, 2005.

Note: Includes Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay and Venezuela.

Source: Irma Arriagada (coord.) (2007), “Familias y políticas públicas en América Latina. Una historia de desencuentros”, Libros de la CEPAL, No. 96 (LC/G.2345-P), Santiago, Chile, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), October. United Nations Publication, Sales No. S.07.II.G.97.

This change means that a high proportion of Latin American family members seek to balance between work and family care responsibilities. Women are especially affected by this transition, given that the cultural expectation remains that mothers (whether real or potential, in effect, all women) continue to have the main responsibility for the care of the home and at the same time participate in the labor market. But while women’s access to paid work has increased and consumes time to deal with family responsibilities, there has not been an equivalent change in the distribution of time that men dedicate to work and to the home. The work overload has fallen upon women, especially mothers with small children. This includes the segment of female-headed, one-parent families in Figure 5.2, which is much more numerous than their male-headed counterparts.

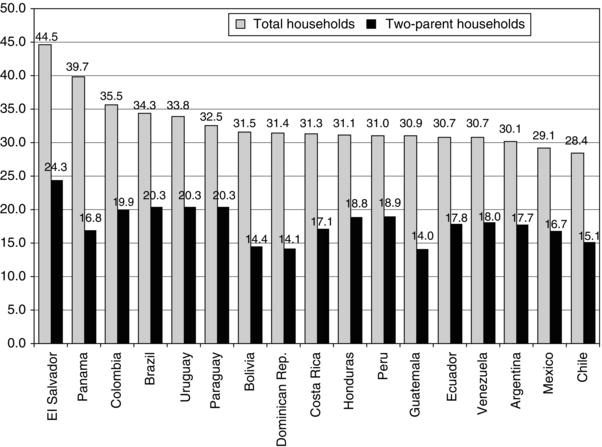

As already noted, the number of women living alone or as heads of households with dependents has been increasing in recent decades, so that the responsibility of women for their own survival and that of their family has also increased. Their children’s fathers often do not support adolescent mothers, and older adults are not cared for by their male children, a tendency that increases the family caregiving load for women. Even when women live with a partner, men’s incomes are often so inadequate that women and children must assume the double load of domestic work and work outside the home to round out the family budget. Even though Mexico has one of the lowest percentages of households headed by women, a study found that the incomes of 17.1% of households, independent of the sex of head of the house, were earned exclusively or predominantly by women (Rubalcava, 1996). In 2008, the economic contribution of women in all households ranged between 44.5% of total household income in El Salvador and 28% in Chile (see Figure 5.3). Likewise, the economic contribution of women in two-parent households was lower but still significant for family budgets. In these households, women’s contributions to total household income were 24.3% in El Salvador and 15.1% in Chile.

Figure 5.3 Women´s percentage contribution to household income for all and two-parent household by country: 17 Latin American countries, 2008.

Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, special tabulations of the households surveys.

The economic contribution of the work by children, especially in indigent households, is also important for the survival of these households. Young people and children in the region work in variable percentages depending on the country and age group. The data underestimate the magnitude of child and youth participation in the labor market, given that legislation in the majority of countries prohibits employing persons under 18 years of age. Nevertheless, it is accepted that children under this age work for a few hours per day, provided they attend school and only perform light work. In the case of households where children work, the children contribute between 16% and 36% of household incomes (Arriagada, 1998).

Information about the labor force participation of women and youth reveals two tendencies: one virtuous and the other negative. The first refers to the fact that the participation of more adult members of the family, mainly women, allows the family to emerge from poverty. The labor participation of children under the age of 18 has negative long-run consequences, however, given that they drop out of the educational system. This results in social and economic limitations for them and their future families and thus reproduces the intergenerational cycle of poverty.

The changing composition of families: Latin American families have become smaller, and their distribution across family life cycle stages has also changed. The reduction in the size of families and households is noted in all Latin American countries, although with significant variations. In 2009, Uruguay has the lowest average household size (2.9 persons), while Peru and Ecuador has the highest (4.0). This is associated with the decrease in fertility, the improved general socioeconomic level allowing family members to live apart, and the increased labor participation rate of women. Other factors include couples marrying at an older age, delaying children, and increasing the space between births. Likewise, the increase in the number of consensual unions has been accompanied by shorter relationships, which suggests the importance of analyzing the characteristics of the affective bonds generated in relationships.

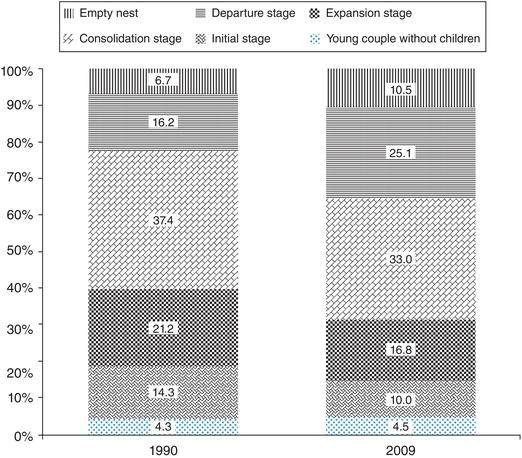

Couples’ transitions over time have given rise to the concept of stages in the family life cycle, a heuristic idea based in procreation within stable unions. Despite the diversity in family structures and experience, the family life cycle remains a useful, if admittedly simplified, way of describing the different phases that couples’ households can go through. Six stages, identified on the basis of the ages of the woman and the youngest child, provide insights into these developments. There is (i) the young couple without children (the woman younger than 40); (ii) then the initial stage of starting a family when the first children are born; (iii) the stage of family expansion when the number of children peaks; (iv) consolidation, when the couple is no longer having babies and the youngest children are adolescents; (v) the departure stage when children are grown and leave home to start their own households; and (vi) the empty nest when an older couple (the woman 40 years or older) no longer have children in the home (Arriagada, 2002).

Due to significant demographic changes, in particular declining birthrates and increased life expectancy, important changes have occurred in Latin America in the distribution of families over each stage in the family life cycle. Based on information from household surveys, the majority of Latin American families are in the stages of family expansion and consolidation, that is, in the stage when the family stops having more children. This is when family resources are under strong pressures given the size of the family and the economic dependence of children 6–18 years of age.

Comparing data from 1990 and 2009, it can be observed that there is an increase in the proportion of families in the stages when the children are over 18 and leaving home as well as when couples are older and have all left home. The increased number of families in the latter stages of the life cycle is explained by the fact that there are more countries in the advanced stage of demographic transition, with the consequent aging of the population. The highest proportions of such households in Latin America are found in Uruguay, Argentina, Chile, and Cuba (Figure 5.4).

Figure 5.4 Percentage distribution of families according to the family life cycle: 18 Latin American countries, 1990–2009.

Note: Includes Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay and Venezuela.

Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, special tabulations of the households surveys.

Class and ethnic inequalities

The family has a long association with processes of social inequality. The reproduction of social inequalities originates in the family system and in the conditions of the class origins of families which determine the future access of family members to social, economic, and symbolic assets.

Notably, in terms of income distribution as measured by the Gini coefficient, Latin America is one of the most unequal regions in the world. The type of family one belongs to conditions the possibility of well-being. In the distribution of household types according to income quintiles, given types of households tend to be concentrated among the poorest or the richest. In 2009, persons in the richest 20% were most in a position to constitute one-person households. Equally, nuclear households with a male head and without children were in the quintiles of families with more resources. In turn, one-parent nuclear families with women as household heads were concentrated in the lowest income quintile. The higher incidence of indigence and poverty among households with a female head is explained by the lower number of economic contributors to the family income and the generally lower incomes of working women.

Thus, the major tendencies observed among families occur with broad diversity among the social groups and classes. For example, the households of families that belong to the highest income quintile have two to three fewer members than families in the lowest quintile owing to the higher number of children among the poorest families. Likewise, extended households are concentrated among the poorest, while one-person households are concentrated among the richest. The levels of well-being are associated with the different stages of the family life cycle. The structures of household expenditures and consumption also vary according to the levels of family income.

Another major source of diversity and inequality is among families belonging to indigenous ethnic groups and Afrodescendents. It is estimated that there are around 670 indigenous groups in Latin America representing between 40 and 50 million persons, concentrated mainly in Mexico, Peru, Guatemala, Bolivia, and Ecuador. Information from some population censuses in or around 2010 indicate higher growth rates of the indigenous population than the nonindigenous, which is consistent with the higher number of children per family among indigenous people.

The information about indigenous people, although fragmented, consistently shows a higher incidence of poverty, lower incomes, lower levels of schooling, lower life expectancy, higher infant and maternal mortality, as well as less access to sewerage systems and potable water (Del Popolo and Oyarce, 2005). Similarly, their values and behaviors in relation to the family differ from those of nonindigenous peoples and also differ among distinct indigenous groups. For example, Aymaras and Quechuas in Bolivia tend to begin their reproductive cycle later than nonindigenous Bolivians and the Guarani in Paraguay. Likewise, the conception of the family and its ideal size varies with ethnic identity, as is shown in this testimony: We have a distinct concept of the family. We can have 5, 6, or 7 children…. Children give the family its value. We appreciate large families. It is selfish to think of having only one child and to give that child everything… (woman of the Ngöbe people). Consistent with this testimony, census data from six Latin American countries for the year 2000 show higher fertility rates among indigenous people than among nonindigenous peoples (Del Popolo and Oyarce, 2005).

It is estimated that 30% of the Latin American population is of Afrodescent, mainly located in Brazil (approximately 45% of the total population) and to a much lesser extent in Ecuador, Costa Rica, Guatemala, and Honduras. An estimated 75 million Afrodescendents live in these five countries. The socioeconomic situation of Afrodescendents varies according to the levels of inequality in the specific countries (Rangel, 2005). In addition to the demographic, social, and economic inequalities suffered by Afrodescendents and indigenous peoples, they face racism, xenophobia, and persistent discrimination by public institutions and the rest of the society.

Gender inequalities in allocation of time

One of the key concepts in the analysis of the interrelation between work and family is the sexual division of labor, which analytically links the two spheres and highlights the mechanisms of the work–family relationship in social reproduction. It refers to daily intergenerational and social care. Numerous studies have shown the unequal participation of men and women in both the labor market and domestic labor. To the extent that the increasing incursion of women into paid work has not been accompanied by an equivalent increase in the participation of men in domestic labor, the workload of women has risen (Ariza and de Oliveira, 2004).

The production of goods and services that takes place in the sphere of the family or through unpaid work does not have public visibility nor is it counted in labor records. Therefore, it has been considered as nonwork according to the usual definitions of work and paid employment. Likewise, the sexual division of labor as consolidated since industrialization associates (more in the collective imagination than in reality) men with economic activities and women with domestic and family activities (Carrasco, 2001). This rigid distribution of tasks hides the contribution of women’s work to family and social well-being. The lack of monetary value attributed to unpaid domestic work impedes an assessment of the real economic contribution of women to the development of countries, to the reduction of poverty, and to the well-being of their families (ECLAC, 2004).

Surveys about time use are essential to understand changes and restructuring resulting from the participation of women in the labor market, because they provide essential quantitative information on the structure of domestic work as determined by the socioeconomic status of the family, its life cycle stage and the place of residence. There are significant differences between men and women in time use in general and particularly in relation to performing unpaid domestic tasks. The model upon which Latin American societies are structured relegates women to private space and the realization of reproductive labors. On the other hand, men are associated with the public space and productive functions. Another factor that influences the variations of the time assigned to reproductive work within the home is the life stage of various household members. The distribution of time dedicated to domestic work varies among women according to their age, marital status, and the number and age of children living in the home. The composition and functions of domestic work differ considerably if the woman is young, single, and with one child as opposed to married with more than two children and in charge of caring for older adults (Aguirre, 2009). Examining domestic work within the family requires incorporating as a central element the concept of the family life cycle, which enriches knowledge of domestic work and its functioning in diverse family structures.

In relation to paid work, women encounter more obstacles than men to entering the labor market and have higher rates of unemployment throughout their working lives. Women are subjected to the vertical and horizontal segmentation of occupations, that is, they work in a narrower range of occupations and are more concentrated than men in informal and low-productivity sectors such as domestic services: “feminized” occupations have consequently lower earnings. The income gap between men and women has been decreasing with time. While in the 1990s, women earned 69% of what men were earning, almost 20 years later in 2008, this gap had been reduced by 10 percentage points, that is, women made 79% of what men earn. Although the proportion of women without incomes of their own decreased by 11 percentage points between 1994 and 2008, over a third of women in urban areas and 44% in rural areas cannot sustain themselves economically. The majority cannot acquire their own monetary resources because of their domestic and caregiving activities at the home. In turn, the percentage of men without incomes has remained relatively stable at around 10%. This situation underlines the persistent vulnerability of women to poverty and inequality (ECLAC, 2010a).

Various time-use surveys that have registered the time dedicated to paid and unpaid activities have been conducted in 16 countries in the Latin American region. Unfortunately, they do not lend themselves to cross-national comparisons owing to differences in recruitment, subject coverage, in situ data collection methods, study population (household, individual, minimum age of interviewees), reference period (day before, week), and, in particular, the activities making up household and caregiving work, and the reporting of simultaneous activities (Durán and Milosavljevic, 2012). Despite the methodological differences that impede comparability, there are a number of general tendencies in time use.

The total work time of women (paid and unpaid) is greater than the total work time of men. According to information from the ECLAC Gender Equality Observatory of Latin America and the Caribbean (www.cepal.org/oig), the average weekly paid and unpaid work time is seen for a number of countries. In Brazil in 2008, men worked 47 h and women 57 h. In Colombia in 2009, men worked 53 h and women 64. In Ecuador in 2008, men worked 52 h and women 66. In Mexico in 2009, men worked 64 h and women 86. In Peru in 2010, men worked 62 h and women 70. Finally, in Uruguay in 2007, men worked 56 and women 79.

Men, of course, are less likely to participate and they invest less time in domestic and caregiving activities than do women. For Mexico in 2010, 52% of men compared to 96% of women devoted at least some time to domestic tasks. The figures for the care of children, the sick, and disabled were 29% of men and 53% of women (INEGI, 2011). In 2002 in Mexico, where women contributed 85 h to domestic work, men contributed only 15% of the total household labor. Women dedicated on average 14 h a week exclusively to caregiving for children and other members of the household, while men contributed only 7.6 h. The number of hours that women dedicate to work increases notably in the stages of the family life cycle associated with raising children, especially when the children are under 5 years of age. Despite the increase of work in the household with small children, the time men dedicate to household work remains constant over the different stages of the life cycle.

Women’s paid workweek is shorter than that of men because women need to attend to domestic and family responsibilities. A survey in Chile in 2007 found that women accounted for 78.2% and men 22.8% of the total time dedicated to caregiving in the home, while women accounted for 66.4% of the time dedicated to household tasks, while men accounted for only 33.6%. On the other hand, the relation was the reverse for paid work: the rate of employment for men was 69% and the rate for women was only 38%.

Even when women have paid work, the distribution of domestic and caregiving work between women and men continues to be unequal. In Mexican families with both partners participating in the labor market, work time is divided in the following manner: on average, male partners work 52 h weekly in their economic activity, and female partners work 37 h. Male partners dedicate 4 h weekly to cleaning house and female partners 15 h; male partners 7 h to cooking and female partners 15.5 h; male partners 8 h to childcare and female partners 12; and finally male partners dedicate 1.5 h to cleaning and care of clothing and female partners 8 h (INEGI, 2004).

Women who have children in one-parent households and who perform unpaid work are shown to work fewer unpaid work hours than women who live with a partner and children. Without a male breadwinner, more of their time is likely to go into paid employment. In 2007, single women with children in Uruguay dedicated 7 fewer hours weekly to unpaid work than women who live with a partner and children (Aguirre, 2009). In terms of increasing unpaid domestic and caregiving work, having a partner or being married is a bad option for women, and their unpaid workload increases in the case of women who belong to blended families.

Cultural changes

Cultural concepts and images regarding male power continue to prevail in the social domain, along with behavioral patterns based on those images. This helps to explain the inconsistencies that exist between the traditional discourse and new family practices. Nonetheless, certain dimensions of modernity have been emerging, such as redefined conjugal roles, in which the principle of equality is gradually gaining acceptance in keeping with the growing economic contribution to the household made by women and children. Changing parent–child relationships reflect a strengthening of the rights of the child and less emphasis on relations of hierarchy and submission. New individual choices (e.g., nonnuclear and single-person households) are emerging, made possible by individual access to economic resources. The institution of the nuclear family centered on paternal authority and supported by all social institutions is being called into question by a number of interrelated processes. These processes include changes in the organization of work in a global information economy; women’s higher levels of education and labor market participation; increasing control over the frequency and spacing of pregnancies; circulation of people and ideas between different societies; and greater conscious awareness of their situation among women themselves (Guzmán, 2002).

Incipient processes of “individualization” are also emerging. Personal rights take precedence over family ones, and personal fulfillment overrides family interests. In these processes of cultural change, globalized images of different family types have fueled the move toward individual rights and autonomy. These go along with changes in models of sexuality and intimacy, especially among adolescents, and a greater emphasis on peer culture (in which young people identify first and foremost with other young people). A study in Chile claims that young people see family relations as problematic. They believe family conflict affects them negatively, and they blame parental attitudes for this. Authoritarianism, mistrust, and a lack of care and affection are children’s most frequent complaints about their family environment (UNDP, 2002).

A number of changes in domestic relationships can also be identified. Compared to earlier studies, a case study conducted in Mexico City and Monterrey shows that women today have greater decision-making power over reproductive issues (use of contraceptives, attending clinics) than in other areas of family life (García and de Oliveira, 2001). The gender-based division of labor for domestic chores shows little change, however. Domestic violence persists in a variety of forms, together with a strong tendency for men to restrict women’s freedom to carry on various types of activities. A large proportion of women still have to obtain permission to undertake paid work, join associations, or visit friends and family. There are still areas of exclusive male decision making, such as what major goods to purchase and where to live. Men and women have strikingly different perceptions of the various issues covered in the survey: in Mexico City, for example, the existence of domestic violence is perceived less clearly by men than by women – 16% compared to 33%, respectively (García and de Oliveira, 2001).

A study in Argentina that analyzed two generations of two-provider families concluded that “the division of labour has moved from the traditional model of segregated roles, to a transitional one….” The generational transition has not been uniform, as paternity gained many more supporters than domesticity. In other words, men increased their participation in childcare much more than in housekeeping chores, which remain largely a female preserve. Although women have not cut back on their participation in domestic and maternal chores, they have begun to encroach on traditionally male activities in the home (Wainerman, 2000, p. 149).

Rapid social, economic, and cultural changes have an impact on family relationships, attitudes, and social practices, given new opportunities (such as the greater autonomy, the possibility of choice with regard to childbearing, and the economic independence for women). These coexist, however, with traditional patterns of behavior, such as subjective feelings of dependency, teenage pregnancy, and gender-based division of domestic chores.

Latin American families have undergone major changes, but these have been more marked in some areas than in others. Patriarchal authority is being called into question, and very incipient democratic models of family reconstruction are emerging. This is increasingly necessary, because families provide psychological security and material well-being to their members in a world characterized by the individualization of work, the breakdown of civil society, and the loss of legitimacy of the State. Nonetheless, the transition to new family forms entails a fundamental redefinition of gender relations in all societies (Castells, 1998). Unlike developed countries, Latin America displays glaring inequalities between families at different economic levels. Public policy formulation therefore needs to consider the fact that the family structures of poorer households limit their chances of escaping poverty. For example, poor households tend to be at the expansion stages in the family life cycle, with fewer economic providers and a larger number of members to provide for. These socioeconomic differences are compounded by gender and ethnic inequalities. These are fundamental issues. When formulating policies and programs aimed at democratizing Latin American families, there is a need to alter the current balance of men’s and women’s rights and obligations in the family domain.

Conclusion

Within the framework of the sui generis modernization and modernity occurring in Latin America, this chapter has analyzed a number of cultural, socioeconomic, and demographic changes that families in the region have undergone. The changes occur against a general backdrop of gender, ethnic origin, and class inequality. Therefore, this paper has considered the historical evolution of family structures associated with modernization in terms of distinctive development paths in different social classes. It has considered the evolution of families over time as they pass through stages of the family life cycle, taking account of the fluidity of family structures and the changes taking place in them. Due to their systemic nature, gender inequities permeate the social fabric, such that overcoming them requires changes in other mechanisms that perpetuate social inequality, hence the analytical importance of an approach that focuses on the overlap between gender and other systems of inequality relating to class, ethnic origin, or life cycle (Salles and Tuirán, 1997; Ariza and de Oliveira, 2001).

There have also been changes in symbolic aspects, reflected in new types of families and family relationships. These occur in the context of societies undergoing continuous processes of change that question traditional family roles and raise new challenges and tensions for their members. In a context of modernization without modernity, family change does not follow a single line but unfolds along a variety of paths heading in different and sometimes opposite directions. The analytical frameworks used to study families reveal a number of limitations in approach and public policy design often because of the assumption that there is a single desirable family model.

In many discourses, the institution of the family is seen as the final bastion against the vicissitudes of modernity, overlooking the fact that the great demographic, social, and economic changes the family has undergone prevent it from adequately performing the changing functions demanded of it. This suggests the existence of unresolved traditional problems (such as domestic violence and rigid sexual division of roles), compounded by new challenges for families that require additional cognitive, material, and sociability resources to address (Güell, 1999). Modernity itself involves the possibility of accepting new forms of family structure and functioning that afford autonomy and reflexivity in decision making for all members. The fact that these processes of reflexivity and change, which often take place privately, are not being adequately reflected in public debate further widens the gap between people’s representations, discourses, and practices.

Revealing the existence of a wide diversity of situations, findings relating to family structures and home life cast doubt on the dominant image of the traditional patriarchal family. At the same time, the separation of sexuality from reproduction, so that motherhood is now a matter of choice, has increased women’s possibilities of gaining access to greater labor market opportunities (albeit often in precarious forms of employment) and taking part in social and political activities. With regard to family forms and functions in a Latin American setting of highly varied modernity, domestic gender inequalities are not only being challenged but also being rebuilt in the wake of the other changes taking place. These include a dual workload for women, the persistence of domestic violence, and more limited autonomy for women.

On the other hand, the stages of the demographic transition tend to overlap even within a given country, depending on whether one is considering sectors of high socioeconomic level or extreme poverty. The social, economic, and demographic changes taking place in Latin America display a number of basic pillars around which old forms of inequality are reproduced and new ones are created which require an integrated multidimensional approach to overcome.

References

- Aguirre, R. (ed) (2009) Las bases invisibles del bienestar social. El trabajo doméstico no remunerado en el Uruguay, UNIFEM, Doble Clic editoras, Montevideo, Uruguay.

- Araujo, K. and Martuccelli, D. (2012) Desafíos Comunes. Retrato de la sociedad chilena y sus individuos, Tomo II, Trabajo, sociabilidades y familias, LOM ediciones, Colección Ciencias Humanas, Santiago.

- Ariza, M. and de Oliveira, O. (2001) Familias en transición y marcos conceptuales en redefinición. Papeles de población, 7 (28), 9–39, Mexico City, April–June.

- Ariza, M. and de Oliveira, O. (2004) Imágenes de la familia en el cambio de siglo. Universo familiar y procesos demográficos contemporáneos, Instituto de Investigaciones Sociales, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico (UNAM), Mexico.

- Arriagada, I. (1998) Latin American families: convergences and divergences in models and policies. CEPAL Review, 65, 85–102.

- Arriagada, I. (2002) Changes and inequality in Latin American families. CEPAL Review, 77, 135–153.

- Arriagada, I. (coord.) (2007) Familias y Políticas públicas en América Latina: una historia de desencuentros, ECLAC Book No. 96, UNFPA, Santiago.

- Arriagada, I. (2012) Diversidad y desigualdad de las familias latinoamericanas. Desafíos para las políticas públicas, Editorial Académica Española, https://www.eae-publishing.com/catalog/details//store/es/book/978-3-8484-7737-1/diversidad-y-desigualdad-de-las-familias-latinoamericanas (accessed November 18, 2013).

- Bourdieu, P. (2001) Masculine Domination, Polity Press, London.

- Calderón, F., Hopenhayn, M. and Ottone, E. (1993) Hacia una perspectiva crítica de la modernidad: las dimensiones culturales de la transformación productiva con equidad, ECLAC Work Document No. 21, ECLAC, Santiago.

- Carrasco, C. (2001) Hacia una nueva metodología para el estudio del trabajo: propuesta de una encuesta de empleo alternativa, in Tiempos, trabajo y género, (compiled by C. Carrasco), Barcelona Publicaciones Universitat, Barcelona.

- Castells, M. (1998) The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture, vols. II and III, Blackwell Publishers, Cambridge.

- Del Popolo, F. and Oyarce, A. (2005) Población indígena de América Latina: perfil sociodemográfico en el marco de la CIPD y de las Metas del Milenio. Presented in the Seminario Internacional Pueblos indígenas y afrodescendientes de América Latina y el Caribe, ECLAC, Santiago, April 27–29, 2005.

- Durán, A. and Milosavljevic,V. (2012) Unpaid Work, Time Use Surveys, and Care Demand Forecasting in Latin America, Fundación BBVA Work Document No. 7, Fundación BBVA, Madrid.

- ECLAC (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean) (2000a) Social Panorama of Latin America, 1999–2000, ECLAC, Santiago.

- ECLAC (2000b) Juventud, población y desarrollo: problemas, oportunidades y desafíos, ECLAC Book No. 59, ECLAC, Santiago.

- ECLAC (2004) Roads Towards Gender Equity in Latin America and the Caribbean, ECLAC, Santiago.

- ECLAC (2007) Latin America and the Caribbean Demographic Observatory Fertility Year III, No. 5, ECLAC, Santiago.

- ECLAC (2010a) What Kind of State? What Kind of Equality? ECLAC, Santiago.

- ECLAC (2010b) Social Panorama of Latin America 2010 (LC/G.2481-P), March 2011, Santiago, Chile. United Nations Publication, Sales No. E.11.II.G.6.

- ECLAC (2011a) Social Panorama of Latin America, 2011, ECLAC, Santiago.

- ECLAC (2011b) Statistical Yearbook of Latin America and the Caribbean, ECLAC, Santiago.

- ECLAC (2012) El Estado frente a la autonomía de las mujeres, Colección La hora de la Igualdad, Santiago.

- ECLAC (2013) Gender Equality Observatory for Latin America and the Caribbean, http://www.cepal.org/oig/default.asp?idioma=IN (accessed June, 2012).

- Esping-Andersen, G. (2009) The Incomplete Revolution. Adapting to Women’s New Roles, Polity Press, Cambridge.

- Fuller, N. (1997) Identidades masculinas. Varones de clase media en el Perú. Catholic University of Peru/Fondo Editorial, Lima.

- García, B. and de Oliveira, O. (2001) Las relaciones intrafamiliares en la ciudad de México y Monterrey: visiones masculinas y femeninas. Paper presented at the Twenty-Third International Congress of LASA, Washington, DC, September 6–8, 2001.

- García, B. and de Oliveira, O. (2011) Family changes and public policies in Latin America. Annual Review of Sociology, 37, 593–611.

- Giddens, A. (1990) The Consequences of Modernity, Stanford University Press, Stanford.

- Giddens, A. (1991) Modernity and Self-Identity. Self and Society in the Late Modern Age, Stanford University Press, Stanford.

- Giddens, A. (1992) The Transformation of Intimacy: Sexuality, Love and Eroticism in Modern Societies, Polity Press, Cambridge.

- Goldin, C. (2006) The quiet revolution that transformed women’s employment, education, and family. NBER working paper no. 11953, American Economic Review, May 2, 2006, v 96, www.nber.org/papers/w11953 (accessed May 2, 2012).

- Güell, P. (1999) Familia y modernización en Chile. Paper presented at the Comisión de Expertos en Temas de Familia, Servicio Nacional de la Mujer (SERNAM), Santiago, December.

- Guzmán, V. (2002) Las relaciones de género en un mundo global. ECLAC Mujer y desarrollo series No. 38, ECLAC, Santiago.

- Guzmán, J.M., Hakker, R., and Contreras J.M. (2001) Diagnóstico sobre salud sexual y reproductiva de adolescentes en América Latina y el Caribe, UNFPA, Mexico.

- INEGI (2004) Encuesta Nacional sobre Uso de Tiempo 2002. Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática, Aguascalientes: Press release, March 8, 2004.

- INEGI (2011) Estadísticas de género Proyecto Interinstitucional. Presented at the XII Encuentro Internacional de Estadísticas de Género: empoderamiento, autonomía económica y políticas públicas, Aguas Calientes, octubre 2011.

- Jelin, E. (1998) Pan y afectos. La transformación de las familias, Fondo de Cultura Económica, Argentina.

- López, P. and Salles, V. (comps.) (2000) Familia, género y pobreza, Grupo Interdisciplinario sobre mujer trabajo y pobreza (GIMTRAP), México.

- Olavarría, J. and Parrini, R. (eds) (2000) Masculinidad/es: identidad, sexualidad y familia. Primer encuentro de estudios de masculinidad, Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences (FLACSO)/University of the Academy of Christian Humanism, Santiago.

- Rangel, M. (2005) La población afrodescendiente en América Latina y los Objetivos de Desarrollo del Milenio. Un examen exploratorio en países seleccionados utilizando información censal. Presented at the International Seminar on Pueblos indígenas y afrodescendientes de América Latina y el Caribe ECLAC, Santiago, April 27–29, 2005.

- Rubalcava, R. (1996) Hogares con primacía de ingreso femenino en Hogares, familias: desigualdad, conflicto, redes solidarias y parentales, Sociedad Mexicana de Demografía (SOMEDE), México.

- Salles, V. and Tuirán, R. (1996) Mitos y creencias sobre vida familiar, Revista Mexicana de Sociología, 59 (2), 117–144, Instituto de Investigaciones Sociales, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico City, April–June.

- Salles, V. and Tuirán, R. (1997) The family in Latin America: a gender approach. Current Sociology, 45 (1), 153–195, Sage Publications, London, January.

- Servicio Nacional de la Mujer (SERNAM) (2001) Mujeres chilenas. Estadísticas para un nuevo siglo, Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas, Santiago.

- Smart, C. and Shipman, B. (2004) Visions in monochrome: families, marriage and the individualization thesis, The British Journal of Sociology, 55 (4), England. http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/3764/2/Visions_in_Monochrome.pdf (accessed November 1, 2013).

- Therborn, G. (2007) Familias en el mundo. Historia y futuro en el umbral del siglo XXI, in Familias y Políticas públicas en América Latina: una historia de desencuentros (coord. I. Arriagada), ECLAC Book No. 96, ECLAC, Santiago.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (1998) Desarrollo humano en Chile. Las paradojas de la modernización, Santiago.

- UNDP (2002) Human Development in Chile We, the Chileans: A Cultural Challenge. Human development report Chile 2002, Santiago.

- Van de Kaa, D. (2001) Postmodern fertility preferences: from changing value orientation to new behaviour, in Global Fertility Transition (eds. R. Bulatao and J. Casterline), Population Council, New York.

- Wagner, P. (1994) A Sociology of Modernity: Liberty and Discipline, Routledge, London.

- Wainerman, C. (2000) División del trabajo en familias de dos proveedores. Relato desde ambos géneros y dos generaciones, Estudios demográficos y urbanos, 15 (1), 149–184, El Colegio de Mexico, Mexico City, January–April.

- Wainerman, C. (2005) La vida cotidiana en las nuevas familias ¿Una revolución estancada? Ediciones Lumiere, Buenos Aires.