7

Family Poverty

Rys Farthing

Poverty is perhaps one of the most extensive and damaging problems faced by families the world over. Poverty is an acute problem in the developing world, where over 1.3 billion people live below the somewhat arbitrarily defined $1.25 per day poverty line (World Bank, 2008), but this suffering is by no means limited to the global south. Amidst the wealth of the global north, in the United Kingdom, for example, 11% of people live below a commonly defined poverty threshold, while in the United States, 17.3% of the population live below this poverty line1 (OECD, 2012).

But to talk about poverty is somewhat different than talking about other problems families might face; to use the phrase poverty is to implicitly invoke an imperative for action against it (see, e.g., Piachaud, 1981). The very word poverty refers to an “unacceptable state of affairs, which requires some sort of policy response” (Alcock, 2008, p. 131). For this reason, the problem of poverty has always been a key concern for both sociologists and social policy makers. Some of the earliest social science researches were directed toward understanding the experience and causes of poverty, such as Charles Booth’s 1880 survey and subsequent typology of poor families in London (Platt, 2005, p. 20). Likewise, some of the earliest social policies were directed toward alleviating the problem of poverty – such as the United Kingdom’s 1597 Poor Law (Platt, 2005).

However, despite the widely acknowledged scope of the problem and the centuries of study and policy directed toward it, much debate about the nature and definition of poverty itself remains. Following this breadth of debate, no singular diagnosis or remedy has emerged; different definitions and measures of poverty produce different visions of poor families and call for different policy responses. Different visions of, and policy responses to, poverty can have profoundly different impacts on the lived experiences of families.

This chapter aims to provide an orientation to this debate. It commences by briefly exploring different definitions of poverty across the world, before turning to look at the global state of family poverty and which families are “poor”. It concludes with an exploration of the lived experience and consequences of poverty for these families, looking at how they “get by” and “get out”, specifically in the global north.

Defining Poverty

Defining poverty is not as straightforward as claims of “people living on incomes below $1.25 a day” might make it seem. Definitions have profound implications for both the way we understand poverty and the way we act toward ending or alleviating it.

Sen (1979) argues the poverty analysis starts with a two-stage process of definition. Firstly, the poor are identified through the creation of some sort of poverty line which the “poor” fall below, and secondly, information is aggregated as these identified “poor” are then counted and measured. Discussions of this sort, around measurement, construct poverty as a distinctly technical concept. However, poverty is more than this technical conceptualization suggests – it is, perhaps firstly, a moral concern. Underneath this technical focus on measurement lies a deeper layer of understanding poverty (Lister, 2004a), where meanings and discourses about being “poor” reside. Lister suggests narrowing our confusion exclusively to technical measures, or indeed starting from measurement first, rather than seeing the broader discourse has the damaging effect of narrowing the sociological focus.

Expanding the focus often requires discussions with “poor” families themselves. Almost by default, technical analysis excludes these families from the process of defining poverty; poverty drastically limits people’s opportunity to become social scientists and take part in technical debates. However, such exclusion is not inevitable. Alongside the analysis rooted in conventional, technocratic understandings of poverty often lies sociological research that adopts participatory approaches grounded in the experiences of the “poor” themselves (Lister, 2004a). Each approach stands to highlight a different, but often complementary, aspect of the experience of poverty.

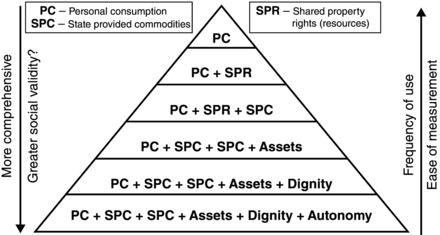

Baulch (1996) visualizes the relationship of these different aspects of poverty as a pyramid (see Figure 7.1). Easy-to-measure and frequently cited manifestations of poverty, such as technical measures of income and consumption, rest on top of a realm of other deprivations associated with poverty, such as assets, dignity, and autonomy. Policy interventions are often aimed at different “levels” in the pyramid and can work to either reduce poverty itself or mitigate its impact on people (Lister, 2004a). Both technical and participatory approaches are, however, not oppositional and can work to reinforce each other; however, what becomes apparent is that each sociological understanding of poverty will call for different interventions.

Figure 7.1 The poverty pyramid.

Source: Adapted from Baulch (1996).

Having established that definitions of poverty are important and expansive, a number of key themes in definitions are notable. Firstly, definitions of poverty can either be absolute or relative. Absolute poverty, while contested in its own right, tends to refer to poverty as a state of being where people are unable to meet the minimum requirements for their physiological well-being, without references to the prevailing social standards within which they live. The “$1.25 a day” measure tends to be regarded as absolute, as it is widely held that below this threshold, basic human needs for food, water, and warmth cannot be met. The official US poverty line, which is calculated by taking the minimum costs of meeting basic nutritional needs multiplied by three (Fisher, 1992), is also regarded as absolute, as it is intended to reflect the ability of households to meet absolute, basic human needs like food, toiletries, and rent.

In contrast, much sociological research focuses on relative understandings of poverty or understanding that poverty is about not having enough to meet what are socially determined minimum needs:

individuals, families and groups in the population can be said to be in poverty when they lack the resources to obtain the types of diet, participate in the activities, and have the living conditions and amenities which are customary, or at least widely encouraged and approved, in the societies in which they belong.

(Townsend, 1979, p. 31)

Alternative understandings suggest that poverty within a society is relative to normal standards of living. Measures such as those used within the EU, which identifies the poor as those living below 50% or 60% of median income, are considered relative, as they refer to people’s ability to meet their needs and participate within their society. Debate about the merits of the two approaches exists (see, e.g., Sen, 1985; Townsend, 1985) and about the scope of their differences (see, e.g., Lister, 2004a). However, generally, absolute poverty holds the persuasive power of recording such a dire state of existence that it cannot easily be contested as a problem, while relative poverty powerfully articulates the nature and experience of poverty as a social issue.

Beyond different approaches as to where to set the threshold, many measures of poverty have been operationalized – beyond the oft-cited income threshold. Income is an indirect measure of poverty; it does not record the nature of deprivations or suffering caused by poverty, but simply measures the resources available to a family to avoid such suffering in the first place. For this reason, income has been described as at best a second rate measure for a low standard of living (Sen, 1981). Direct measures of poverty – such as deprivation measures – are possible (Mack and Lansley, 1985) and attempt to capture the lack of welfare people experience as a result of their poverty. They often measure the material goods and resources available to households, and this alternative focus can lead to policies directed at providing more public resources (such as health care and education) instead of, or in conjunction with, policies designed to improve family incomes. Deprivation measures can be measures of absolute poverty, such as the World Bank’s measure of the prevalence of malnutrition in children under 5 years old. Alternatively, they can be relative and capture people’s inability to live in way regarded as socially acceptable, such as the ability to replace worn-out furniture or go on holiday for 1 week of the year (DWP, 2011).

While this may seem like an abstract theoretical discussion, how we define poverty drives policy responses to the problem and profoundly impacts the lives of “poor” families. As a powerful example, in the United Kingdom, the idea of “poverty” was undermined within political discourse over the 1980s, with politicians declaring the concept no longer relevant (Alcock, 2008, p. 132). As the Secretary of State for Social Security noted, “when pressure groups say that one-third of the population is living in poverty, they cannot be saying that one-third of people are living below…draconian subsistence levels” (Moore, 1989) and went on to suggest that it was “utterly absurd” to talk of British poverty. According to the then Secretary of State, people who spoke of British poverty should be dismissed because “their motive is not compassion for the less well-off… Their purpose in calling ‘poverty’ what is in reality simply inequality, is so they can call western capitalism a failure” (Moore, 1989). However, under this government’s rule and in the decade prior to his speech, poverty, as measured by the United Kingdom’s now preferred relative definition,2 increased from 7.1 million people or 13.4% of the population in 1979 to 11.8 million or 21.5% in 1989 (IFS, 2010). When “poverty” was accepted by and reintroduced into political discourse in 1999 (Platt, 2005), policies aimed at increasing family incomes, and financial redistribution reduced child poverty figures by 900,000 over 13 years (DWP, 2011). These two approaches, of viewing poverty as an absolute construct akin to the destitution, or as seeing it as a relative problem of low incomes in a time of affluence, produced different policy approaches – such as the provision of minimal, subsistence level support versus a strong redistributive tax and benefit system – which in turn produce two distinctly different lived experiences for families.

While sociological understandings of poverty have evolved even further into complex multidimensional measures or concepts of social exclusion, they are beyond the scope of this chapter.

The State of World Poverty and Consequences for “the Poor”

Some 22.4% of the world’s population, or 1.29 billion people, lives on an income of below $1.25 per day (World Bank, 2008). While almost half of these people live in South Asia, sub-Saharan Africa suffers from the highest proportion of poverty (Table 7.1).

Table 7.1 The number and proportion of people living below the $1.25 poverty threshold by region, 2008

Source: Data from World Bank (2008).

| Number of poor at $1.25 a day (PPP) (millions) | Poverty headcount ratio at $1.25 a day (PPP) (% of population) | |

| East Asia and Pacific (developing only) | 284.36 | 14.34 |

| Europe and Central Asia (developing only) | 2.23 | 0.47 |

| Latin America and Caribbean (developing only) | 36.85 | 6.47 |

| Middle East and North Africa (developing only) | 8.64 | 2.7 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa (developing only) | 386.02 | 47.51 |

| South Asia | 570.89 | 35.98 |

| Low and middle income | 1288.99 | 22.43 |

People living in these extremely poor families invariably have fewer choices available to them, as much of their limited income needs to be spent on basic sustenance. A survey of 13 low-income countries found that 56–78% of household limited income was spent on providing food for the family (Banerjee and Duflo, 2007). However, while it is tempting to think of the extremely poor as hungry and spending every penny on food, this view denies the, albeit limited, choices these families have. The same survey found that in many places around the world, spending on festivals was a sizeable part of the family budget. For example, in the Udaipur region of India, a median of 10% of the annual household budget was spent on weddings, funerals, or religious festivals (Banerjee and Duflo, 2007, p. 146). The very human needs of extremely poor families are not dissimilar to the needs of the nonpoor; the need for food, shelter, and warmth coexists with the need to participate in the society. Extreme poverty does not necessarily change family needs; rather, it sharply curtails the ability to meet their needs.

Extreme poverty has severe impacts on people’s health. For example, the chances of a family’s children surviving beyond the age of 5 are, to a large extent, dictated by the poverty of the region they are born into. For example, in 2010, the mortality rate for under 5-year-olds in low-income countries was 107 deaths per 1000 live births but only 6 deaths per 1000 in high-income countries (World Health Organisation, 2012). What causes the deaths of the extremely poor adults also differs, with 58% of deaths in low-income countries attributable to communicable diseases, infections, and nutritional deficiencies compared to 7% in high-income countries (World Health Organisation, 2012).

Beyond limited means and poorer health outcomes, the extremely poor speak of a lack of well-being, a crushing lack of choice, and the overall sense of powerlessness that the lower portion of Baulch’s (1996) pyramid conceptualized. The Voices of the Poor study (Deepa et al., 2000) captured the thoughts of 40,000 poor people from 50 countries around the world, who spoke of an overall sense of ill-being:

Poverty is pain; it feels like a disease. It attacks a person not only materially but also morally. It eats away one’s dignity and drives one into total despair

– Moldova (Deepa et al., 2000, p. 6)

Poverty is lack of freedom, enslaved by crushing daily burden, by depression and fear of what the future will bring

– Georgia (Deepa et al., 2000, p. 31)

These descriptions are echoed in the global north, where the experience of poverty has been described as “going short materially, socially and emotionally” (Oppenheim and Harker, 1996, p. 5):

…Living in poverty puts you under constant pressure. It wears you down

– EU (Czech Presidency of the European Union, 2009, p. 5)

Living in material poverty means they have stolen our here-and-now. And they are stealing our future by keeping us out of touch with the knowledge-based society

– EU (Czech Presidency of the European Union, 2009, p. 5)

However, within the global north, the $1.25 absolute poverty line is too acute to accurately capture this experience of families “going short”. Instead, a relative income threshold paints a more compelling picture. Using the relative threshold of 50% of median income after taxes and transfers and adjusted to reflect household size, 11% of the population of the OECD live in households that are in poverty (see Table 7.2).

Table 7.2 The proportion of the population living below 50% of median household income, equivalized for size, after tax and transfers by selected countries

Source: Data from OECD (2012).

| Country | Poverty rate after taxes and transfers, 50% of current median income | Year |

| Australia | 14.6 | 2007/2008 |

| Austria | 7.9 | 2008 |

| Canada | 12.0 | 2008 |

| Denmark | 6.1 | 2007 |

| Finland | 8.0 | 2008 |

| France | 7.2 | 2008 |

| Germany | 8.9 | 2008 |

| Greece | 10.8 | 2008 |

| Ireland | 9.1 | 2008 |

| Israel | 19.9 | 2008 |

| Japan | 15.7 | 2006 |

| Korea | 15.0 | 2008 |

| Mexico | 20.1 | 2008 |

| Netherlands | 7.2 | 2008 |

| Norway | 7.8 | 2008 |

| Spain | 14.0 | 2008 |

| Sweden | 8.4 | 2008 |

| Switzerland | 9.3 | 2008 |

| United Kingdom | 11.0 | 2007/2008 |

| United States | 17.3 | 2008 |

| OECD total | 11.1 |

For members of these households, their ability to participate within their society is limited. Direct measures of deprivation available from the United Kingdom, for example, show that children in lower-income families miss out on activities that could be considered a regular part of growing up in the United Kingdom, such as celebrating special occasions or owning a bicycle (DWP, 2011). While such deprivation seems a long way from the child mortality noted in the developing world, growing up with these relative deprivations limits childhoods:

I would like to be able to do more things with my friends, when they go out down the town and that. But we can’t always afford it. So I got to stay in and that, and just in here it’s just boring – I can’t do anything.

(Mike 12, in Ridge, 2002)

Which Families are Poor and Why?

Just as the global geography of poverty differs, so too does its demographics. The risk of poverty is not spread evenly, and some families are more at risk of poverty than others. Poverty disproportionately affects families during certain periods of the life course, families headed by women, single-parent families, and families affected by disability.

Families across the life course

One of the earliest sociological studies of poverty conducted by Seebohm Rowntree in 1901 noted that poverty appeared to follow a fairly regular life course. For any individual, the risk of living in poverty increased:

- During childhood, when family incomes were generally lower because most family members were either too young to work or unable to work due to childcare commitments

- Relatedly, when a family had younger children

- In old age, when the ability to earn is often curtailed by poor health.

In between these phases were brief periods of comparative prosperity: during youth when the ability to earn an income was high and later in life when children could provide for themselves but before retirement (Rowntree, 1901).

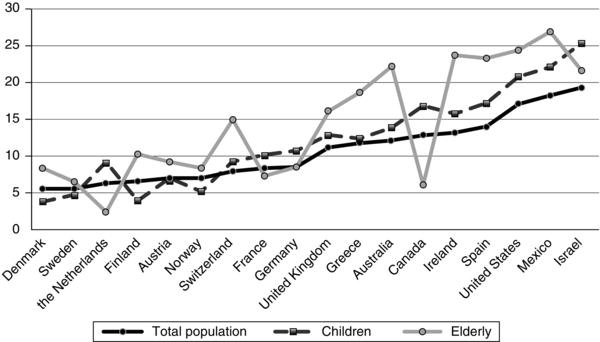

This cyclical pattern is still notable in many countries. As Figure 7.2 highlights, the poverty rates for both children and the elderly – as marked by grey and dashed lines – tend to be higher than the overall poverty figures – marked by a black line. This is especially true in countries that have overall higher rates of poverty, including the United States and the United Kingdom, where higher risks of poverty exist for children and the elderly.3 However, some other countries, and especially those that have managed to achieve low levels of overall poverty, appear to have broken the link between poverty and age. For example, child poverty is lower than overall poverty in the Scandinavian nations. This could be the result of universal income maintenance payments to children and highly subsidized childcare. However, rates of poverty among elderly persons in Scandinavia are higher, which may be the result of the failure of earnings-related social insurance schemes to protect those with a history of low wages or intermittent work.

Figure 7.2 Percentages of people living below 50% of median household income, equivalized after tax and transfers by age, mid-2000s.

Source: Data from Luxembourg Income Studies (2012).

Children face a higher risk of poverty than adults partly because of the reasons Rowntree articulated in 1901 and because of changing family demographics including the rise of single-parent families (see discussion later), among other reasons. However, measures of poverty are perhaps inevitably going to record higher levels of child poverty due to their equivalized nature. That is, calculations of household income are “equivalized” to reflect household need by dividing the total income by some sort of denominator reflecting family size. Children will therefore inevitably increase family poverty levels as they increase the denominator.4

Child poverty is of particular concern for many families, because of the ability of childhood poverty to scar individuals into adulthood. Poverty during childhood can impact on a child’s individual physical, cognitive, and emotional development, reduce educational and health outcomes, and reduce overall well-being long into adulthood. For example, across the global north, there is a negative association between educational outcomes and socioeconomic status (see, e.g., the association between socioeconomic background and reading performance in OECD (2010)), which we could expect to suppress future wages. There are many reasons for this association that suggest that poverty itself might be causal. For example, epidemiologists have shown that the poverty-related stress in early childhood reduced children’s cognitive abilities (Duncan and Brooks-Gunn, 1997), and there is much evidence to suggest that poor parents cannot purchase the educational extras, like books and school trips, that richer parents can (Department for Education, 2007). We also know that increasing family incomes can make a difference in children’s education outcomes. In the United States in the 1990s, for example, when the Earned Income Tax Credit increased, so too did the poorer children’s educational attainment (Dahl and Lochner, 2008).

Childhood poverty is also associated with many health problems in adulthood, including hypertension, arthritis, and limiting disabilities (Melhuish, 2012), which can again decrease potential earning power. Evidence also suggests that childhood poverty can limit future aspirations (Attree, 2006).

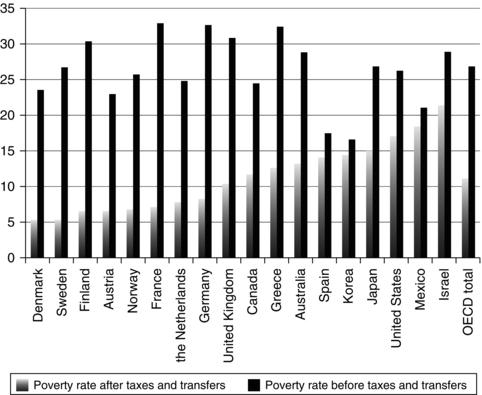

Returning to cross-national variation in poverty, data suggest that there is a large role for the state to play in reducing poverty, and one of the key ways this is achieved is through the use of the tax and benefit systems. As Figure 7.3 highlights, countries like the Scandinavian nations that have low levels of income poverty, as measured after taxes and benefit transfers, have similar levels of poverty if household income is calculated before taxes and transfers. The effect of the tax and benefit system is generally progressive; household incomes calculated after tax and benefit show lower levels of poverty across most countries – the issue becomes a matter of how successfully tax and benefits work to reduce poverty.

Figure 7.3 Percentage of people, pre tax and transfer and post tax and transfer, living below 50% of median incomes across the developed world, mid-2000s.

Source: Data from OECD (2012).

Outside of the state, the market and the family also have a role to play in determining a household’s risk of poverty. While the market often provides routes out of poverty through the provision of employment, market inequalities can exacerbate poverty (see, e.g., Esping-Anderson, 1990), and where work contracts, it can create poverty. Further, work alone is not a guaranteed route to prosperity (discussed further later). Family structures are equally important in mediating risks of poverty; for example, poverty among the elderly is often reduced by living with extended family (Rendall and Speare, 1995). The role of the family often interacts with the role of the state and the role of the market in shaping the risks of poverty. For example, family composition can compensate for limited state spending on benefits (Tai and Treas, 2009) or impact on parent’s ability to work by providing informal childcare (Wheelock and Jones, 2002).

Women in families

Poverty has a feminine face around the world. Poverty rates across the EU, for example, show that in 2010 women were 9% more likely to be in poverty5 across all 27 member countries (EUROSTAT, 2012). In the United States, 16.2% of all women live below their poverty threshold compared to 14% of men (2010 data, CPS, 2011). In the developing world, the UNDP estimates that women and girls account for 6 of every 10 of the world’s poorest (UNDP, 2011). Women are also more likely to have experienced poverty at some stage of their lives, and are likely to have recurrent or longer spells of poverty (Lister, 2004a, p. 55).

Female poverty reflects the economic marginalization of women. As the UNDP puts it, “women perform 66 percent of the world’s work, produce 50 percent of the food, but earn only 10 percent of the income and own only one percent of the property” (UNDP, 2011, p. 1). The reasons behind this are historically and culturally complex but generally include lower levels of employment, lower levels of wages, and higher levels of precarious employment in the informal sector employment (outside of government regulation) (UNIFEM, 2005, p. 2). In the United Kingdom, the gender pay gap was 9.1% (calculated hourly)6 in 2011 (ONS, 2011b), while in the United States in 2009, it was 19.8% (calculated weekly) (US Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2010).

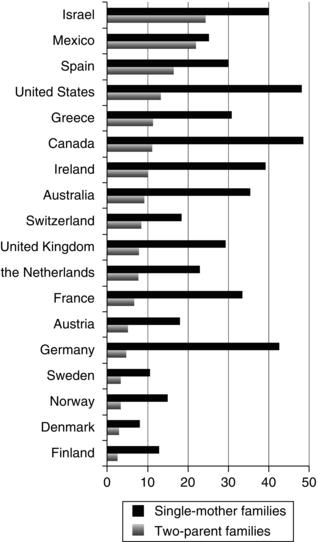

Female-headed families suffer a greater risk of poverty. Female-headed families can result from the death of a partner (especially in the global south), divorce, or births that occur outside of marriage. While these phenomena could result in either female- or male-headed single-parent families, the vast majority of single-parent families are headed by women; for example, in the United Kingdom in 2011, 92% of single-parent families were headed by women (ONS, 2012), while in the United States, 73% of nonhusband/wife families were headed by women (CPS, 2011). Single-parent households are exposed to greater risks of poverty perhaps because of the inevitable trade-off between earning and child caring. Using the official US poverty measure in 2010, for example, 34.2% of all people in female-headed families without spouses live below the poverty line, compared to 17.3% of people in male- headed households without a spouse and compared to 15.1% of all people (CPS, 2011). This relationship – between gender, single parenthood, and poverty – strongly affects childhood poverty rates (see Figure 7.4).

Figure 7.4 The percentage of children growing up in households below the 50% of median household income by family type, mid-2000s.

Source: Data from Luxembourg Income Studies (2012).

Poverty also affects women in male-headed households, and this may be somewhat obscured by the way we measure poverty. Poverty counts for individuals within households are calculated using household income, and rest on the heroic assumption that household income is shared evenly between all members of the household. This may result in “hidden poverty” (Lister, 2004a, p. 56) or people within otherwise nonpoor families suffering poverty due to unequal distribution of household resources. Hidden poverty is widely regarded to be a female problem (Glendinning and Millar, 1987). Studies attempting to measure hidden poverty are few and far between, but some authors (such as Lundberg et al., 1997, Ward-Batts, 2008) have found that in small case studies, households do not share money and resources equally, which may make household income an inappropriate way to estimate female poverty levels.

On top of intrahousehold economic marginalization, many studies note that women self-sacrifice, going without food, clothing, and warmth, to meet their families’ needs first (Middleton et al., 1994). Kabeer (1995) also found that women in Bangladesh will go without food to feed their husbands. Hidden female poverty therefore reflects two concurrent phenomena: structural issues that reduce women’s financial resources and create economic dependence and agentic issues surrounding women’s willingness to sacrifice their own needs to meet their families’ (Lister, 2004, p. 57).

Families affected by disability

Families affected by disability are more likely to suffer from poverty, and the relationship between the two issues is complex. The “social model” of disability suggests that a disability emerges from the interaction between a person’s individual functioning and their social and built environment. For example, someone with mobility issues might not be disabled in a society where transport is made accessible to them, while in a different society the exact same impairment may create a severe disability. Under the social model,

people are not identified as having a disability based upon a medical condition (rather by their) environment that erects barriers to their participation in the social and economic life of their communities.

(Braithwaite and Mont, 2009, p. 220)

Families affected by disability are too often unable to participate in the economic life of their communities. They suffer from higher risks of poverty the world over, from Europe and Central Asia (Elwan, 1999, Braithwaite and Mont, 2009) to the United Kingdom where 9% of individuals without a disability live below the poverty line, compared to 11% of people with disabilities7 (DWP, 2011).

The experience of poverty among families affected by disabilities is in part due to the extra costs of impairments and disabilities, such as paying for medication, necessary equipment, and installing adaptations in homes. It “seems obvious” (Braithwaite and Mont, 2009, p. 222) that the costs associated with avoiding deprivation are going to be higher for families affected by disability than those not affected by disability, or as Lister puts it, “an income of ‘X’ may be adequate for a non-disabled person but may mean a lack of capabilities and poverty for a disabled person” (2004a, p. 65).

But they are also in part due to the opportunity costs associated with the reduced ability to work. Disability can present a barrier to earning an adequate income, for both the person with a disability and the family members who may need to juggle work and caring commitments. People with disabilities are less likely to participate in the labor market; in the United Kingdom in 2001, for example, approximately 48% of the disabled population were economically inactive, compared to 15% of the nondisabled population (Smith and Tworney, 2002, p. 415). But disability also affects the labor market participation of the whole family; the same survey found that 31% of households containing a family member with a disability were workless, compared to 10% of families without a disabled member (Smith and Tworney, 2002, p. 415). Where people with disabilities are able to participate in the labor market, they often have substantially lower wages (Kidd et al., 2000, Schur et. al., 2009). While these lower rates of labor market participation and wages may in part be due to health problems or work-related impairments, there is much evidence to suggest that people with disabilities face very high levels of discrimination within the workplace (Schur et. al., 2009). Disabilities that face higher levels of social stigma are associated with lower levels of pay (Baldwin and Johnson, 2006), and employer discrimination often dictates outcomes for employees with disabilities (Schur et. al., 2009).

Disability-related poverty overlaps with female poverty, as the majority of people with disabilities are female (Lister, 2004, p. 64), and disabled women appear to have even worse labor market outcomes. For example, in the United Kingdom in 2001, 44% of men with disabilities were economically inactive compared to 52% of women with disabilities (Smith and Tworney, 2002, p. 415).

Living in Family Poverty

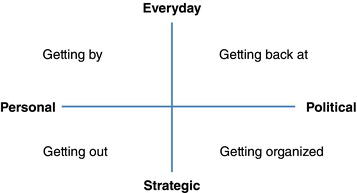

When a family finds itself in poverty, its experience and responses vary greatly. Lister (2004a) talks about four domains of response to poverty, ranging from the personal to the political and the everyday to the strategic (Figure 7.5). This section sketches out family responses across these domains, outlining how families “get by” and mediate the worst effects of poverty and how families attempt to get out of poverty by boosting family incomes as well as attempt to “get back at” and “get organized” against their situations. For brevity, it will largely use the United States and the United Kingdom as case studies.

Figure 7.5 Adaptation of Lister’s (2004a) model of understanding responses to poverty.

Getting by

The art of “getting by” and making ends meet requires balancing limited resources with family demands. It requires attempts to both increase family resources and decrease consumption. This delicate, and often complicated, balancing requires immense financial management and budgeting skills.

Low incomes often mean that family budgets are stretched and meticulously managed. Priorities are determined and money is set aside to meet them, so that wages and benefit payments are often “spent” before they even arrive. Women normally take on the role of managing extremely tight family budgets (Pahl, 1989) and, as discussed earlier, often cut back on their own consumption first. Spending priorities of low-income households generally include meeting housing costs and paying essential bills like electricity, followed by food and other discretionary spending such as clothing (see, e.g., Farrell and O’Connor, 2003). However, unexpected expenditures, like replacing a broken fridge and paying debt, often interfere with such well-ordered priorities (Farrell and O’Connor, 2003).

Food is often purchased on the first day that wages or benefits arrive (Dowler, 1997), and a range of purchasing and consumption strategies are employed to stretch out the pantry. Using discount stores, shopping at many different stores, taking advantage of money-off specials, and purchasing exactly enough of the same few items that you know your family will eat are common approaches (Wiig and Smith, 2009). While buying in bulk might seem sensible to reduce costs, often bulk purchasing is difficult for low-income families; in the United Kingdom, buying a little and often is one tactic to ensure family members do not casually consume what needs to last (Dobson et al., 1995). In the United States, many bulk stores do not accept food stamps (Wiig and Smith, 2009) or require up-front membership fees. While cutting back on food is not the most desired way of coping, food expenditure is often reduced because of necessity, with, for example, “potluck stew” (made with whatever is left in the cupboard), allowing families to pay bills (Dowler, 1997). One study of the dynamics of food expenditure following an increase in disposable income for low-income families found that

food shopping became more spontaneous, less frequent, as households started to bulk buy, and was bought from better quality outlets. …quantity increased first, followed by quality as households’ incomes increased. Meals became healthier and more well-balanced, with the introduction of more meat and fresh fruit and vegetables.

(Farrell and O’Connor, 2003, p. 5)

Budgeting strategies are influenced by the benefit system with which a family lives. In the United States, the monthly “food stamp cycle” can lead to a feast at the beginning of the month and a famine toward the end of the month and can alter family members’ metabolisms (Dinour, Bergen, and Yeh, 2007). Food stamps are occasionally traded in order to cover other household expenditure but seldom go unused, while the annual Earned Income Tax Credit payment is frequently used to pay off credit card debts (Duerr, 1995, Leibman, 1999). In the United Kingdom, fortnightly benefit payments mean a more condensed spending cycle; however, the payment of different benefits at different times, especially universal child benefit payments, enables different spending strategies (Walker, Middleton, and Thomas, 1994).

Benefit payments can be the main source of income for families living below the poverty line – however, rarely are they enough to lift families out of poverty. While there have been some arguments suggesting that receipt of benefits creates a culture of dependency, so that “getting by” requires an adaptation to a benefit “lifestyle” (Murray, 1984; Mead, 1993), this belief rests on two assumptions that have not been proven. Firstly, it assumes families respond directly and only to the incentives or disincentives created by benefit regimes, and secondly, it assumes the receipt of benefits, and the poverty that this is said to cause, is persistent (Gordon and Spicker, 1999, p. 36). The evidence that this happens on a large scale is limited and contested (Walker, 1994). Research into poverty dynamics, suggests most spells in poverty tend to be short (Jenkins 2011, Walker 1994) and families respond to competing incentives, such as a desire to avoid the stigma associated with receiving “welfare”. This stigma often prevents families claiming benefits where they can possibly scrape by without them. In the United Kingdom, the take-up rates of income support are lower than the take-up of council tax benefits among pensioners partly because of the greater stigma associated with income support (Hernandez, Pudney, and Hancock, 2007). In the United States, stigma reduces the take-up of Medicaid (Stuber and Kronebush, 2004).

Budgeting also involves balancing competing demands from different household members. As discussed earlier, women typically treat their children’s and partner’s demands as a higher priority than their own. Children’s needs regarding education are often regarded as a very high priority (Middleton, Ashworth, and Walker, 1994). Alongside this, children’s need not to be singled out as different from their peers, especially when it comes to wearing branded clothing and shoes, can also be prioritized (Hamilton, 2012).

Children themselves are often acutely aware of their family’s financial situation and will limit their consumption (and desired consumption) accordingly. They limit on family budgets and often self-exclude, by, for example, not taking home notes about costly school trips (Ridge, 2002) or not asking for gifts on special occasions (Attree, 2006). Children have their own ways of managing within tight budgets, often working part-time jobs, relying on extended family support, or saving up to buy their own consumer goods (Ridge, 2002; Attree, 2006). Regardless, children in low-income families can still place demands on family budgets that cannot be met, causing stress and conflict. Children report a repertoire of techniques, from persistent asking and reframing requests as school related (Ridge, 2002) to more confrontational techniques like tantrums (Walker et al., 1994). Poverty is acutely felt by parents who cannot afford to say “yes” to a child who refuses to take “no” for an answer.

Getting out

Alongside these time-consuming and stressful strategies to get by while living in poverty, families also negotiate the difficult task of “getting out” of poverty. Research from both the United States and the United Kingdom shows that the state of poverty is dynamic and that very few families remain poor forever, challenging the idea of an underclass.

In the United Kingdom, for example, longitudinal data show that between 1991 and 2003, just under half of the British population were affected by poverty at some point,8 which is almost double the proportion of people affected by poverty in any given year. And the same holds for dependent children in families; around one-half were living in poverty at some stage between 1991 and 2003 (Jenkins, 2011, p. 217), with all of the subsequent implications for their development discussed earlier. This means that there is a fairly large “churn” of poor families, with family incomes moving in and out of poverty in different years. The majority of poverty spells are short, with the length of time in poverty somewhere between 1 and 2 years; however, around one in ten people spends at least 8 out of 10 years poor (Jenkins, 2011, p. 229). Relatively long spells in poverty tend to be experienced by single-parent households and the elderly (Jenkins, 2011, p. 17).

Increased earnings by the head-of-household account for the vast majority of poverty exits, but many poverty exits are also precipitated by income from second earners as well as demographic changes. Changes to household labor earnings accounted for 59% of poverty exits between 1991 and 2004, with other income changes and demographic events making up the rest (Jenkins, 2011, p. 245). On the flip side, demographic changes, like divorce or having children, as well as decreased earnings, accounted for half of all entries to poverty over the same time (Jenkins, 2011, p. 262).

Using data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), Rank and Hirschl (2001) suggest a little over half of American adults will have experienced poverty9 by the age of 65. As the individual risks of any adult entering poverty were around 3% in the 1980s and 4% in the 1990s (McKernan and Ratcliff, 2002), this suggests poverty in the United States is just as dynamic as it is in the United Kingdom. The risks of entering poverty are higher for women, people in female-headed households, people with lower levels of education, and blacks and Hispanics (McKernan and Ratcliff, 2002).

The duration of poverty in the United States also appears to be short. Bane and Ellwood (1986) and Stevens (1999) estimate that around half of the people who enter poverty remain poor for 1 year, while around three-quarters remain poor for less than 4 years. Again, demographics matter in the duration of poverty; poverty spells for blacks and Hispanics are more often longer than they are for whites and for individuals from female-headed households than couple-headed households (Stevens, 1999). Welfare reform in 1996, however, limited the lifetime receipt of benefits for needy families to 60 months.

Labor market events play a significant role in both entry into and exit from poverty in the United States. Reduced family income, including job loss and reduced earnings, account for about half of all entries to poverty (Bane and Ellwood, 1986). Moving from a couple- to a single-parent-headed household and the birth of a child also play a role (Bane and Ellwood, 1986; McKernan and Ratcliff, 2002) but far less frequently. Relatedly, increases in earnings account for almost two-thirds of exits from poverty (Bane and Ellwood, 1986; McKernan and Ratcliff, 2005), but so too does shifts from female-headed households into a couple and increased educational attainment (Bane and Ellwood, 1986; McKernan and Ratcliff, 2005).

While employment is one of the key routes out of poverty, work is not necessarily a guaranteed route out. In 2004, for example, 83.4% of the UK poor and 62.2% of the US poor lived in households headed by an employed person (LIS, 2012). The issue is not that the poor do not work, rather that the labor market cannot guarantee an income above the poverty line. Low-paid jobs, part-time and insecure employment, and a lack of career progression all combine to produce working poverty. Quite often, people boost their incomes by working simultaneously in a number of low-paying jobs. While some people who gain a foothold in work progress rapidly, low-paid work typically offers little security and few prospects (Holtzer and Lalonde, 2000). Indeed, it is likely that the pattern of recurrent spells of poverty is often shaped by a life spent on the margins of work (Walker, 1994). Aside from low incomes, work can generate other insecurities; waiting a month for the first paycheck without savings to help tide your family over, mounting childcare bills, a lack of certainty about in-work benefits, and, in the United States, the end of health coverage can all make taking low-paid, part-time work a risky business.

Means-tested and out-of-work benefits can also make taking employment tricky. In the United Kingdom, for example, some benefits are conditional on recipients not working, while others are withdrawn sharply as income increases. This may create a conundrum where some families may not be financially better-off for working (see, e.g., CSJ, 2009). Indeed, after the costs of working, such as transportation, are deducted, families may be financially worse off for taking employment. Claimants are therefore faced with being penalized by very high withdrawal rates and working for very little or no financial gain, or being criminalized for not reporting their earnings or not taking work, thereby confirming to themselves and others that they have joined Mead’s (1993) dependency culture.

For low-income, single-parent families, child support from nonresident parents can be a significant source of income (Ha, Cancian, and Meyer, 2007). However, many nonresident parents are themselves affected by poverty; the US evidence shows that the nonresident fathers of children in receipt of benefits often have very low earnings and unstable employment patterns (Cancian and Myer, 2004). These fathers are therefore less able and likely to pay child support (see, e.g., Sorensen and Zibman, 2001). Claiming support from nonresident parents can be fraught with difficulties, particularly where abuse or matters of child custody arise.

Getting back at

The extent to which lower-income families engaged in illicit coping strategies is contested; however, it is indisputable that some do. For some people, the need to support a family means they do not declare income to tax or welfare authorities or they engage in other illegal means of raising income: theft, peddling drugs, prostitution, and robbery (Kempson, 1996; Edin et al., 2000).

There is, however, some debate about how much such illegal activity – and especially “benefit fraud” – is actually an attempt to “get by” and cope. Gilliom (2001), for example, notes that low-income mothers in Appalachia use age-old survival tactics like selling haircuts to get by, and that this has simply continued despite newer welfare regimes which have rendered such activities illegal. They regard their actions necessary to survive. Jordan (1996) talks of benefit fraud in the United Kingdom as a type of everyday resistance, which families choose to engage in as a form of compensation for their social marginalization. The extent to which benefit fraud is an attempt “to get” by or an attempt to “get back” probably depends on the individual family and their circumstances more than either theory could capture.

Likewise, while there is much debate around the relationship between poverty rates and neighborhood crime, the general conclusion is that higher levels of poverty lead to higher levels of neighborhood crime (Hipp and Yates, 2011). According to Wilson (1997), when there are extremely high levels of poverty in an area, crime rates increase exponentially. He posited a downward spiral within deprived communities; once crime becomes rife, a neighborhood acquires a reputation that increases the stigma for law-abiding citizens (Wilson, 1997). Indeed, neighborhoods can acquire negative labels even in the absence of crime merely on account of the fact that they house disproportionate numbers of low-income families (Power and Tunstall, 1995). While there is limited evidence to suggest that such extreme downward spirals are common (Hipp and Yates, 2011), community poverty, crime, and ghettoization may lead to disinvestment, where retailers and employers leave an area, decreasing local property values and employment opportunities. However, it is worth noting that the reverse process – gentrification – common in urban areas the world over, sees cycles of investments that often crowd out low-income families from neighborhoods as prices increase (Atkinson and Bridge, 2005).

Illicit activity may be a symptom of a family’s failure to cope under the stress of poverty. People who are financially desperate may be more vulnerable than most to swindles and fraud or to being drawn into criminal activity. Also, a proportion will be further burdened by illiteracy, disability, mental illness, and/or substance abuse and become trapped in a vicious cycle that demands ever-greater coping expertise from people who are the least able to cope (Kempson, 1996; Ramey and Keltner, 2002). Some crimes, such as Medicaid fraud in the United States, can be an institutionalized effort by businesses that exploit the poor to boost revenue.

Getting organized

Collective action against poverty, while necessary to tackle this decidedly social problem, is not especially common. This is partly because the collective identity needed to underpin such a movement is lacking. Identifying and collectively organizing as “the poor” is difficult; being “poor” is a stigmatizing and shameful identity actively rejected by many families and, as noted earlier, is often a temporary experience. As Lister (2004b) put it, such collective identity

is difficult when “poor” represents a shameful economic condition to be endured rather than an individual, never mind collective, identity to be embraced. Disabled people and gays and lesbians have been able to transform a negatively ascribed category into positive affirmation of a collective identity as the basis of a politics of recognition of their own difference. But “proud to be poor” is not a banner under which many want to march. And the last thing people in poverty want is to be seen as different (http://www.theguardian.com/comment/story/0,,1352913,00.html).

Nonetheless, since there is no singular experience of poverty and people who are poor are heterogeneous in their responses, collective actions by “the poor” against their economic and political marginalization exist and have been successful in many cases.

Firstly, economically speaking, the existence of food cooperatives, credit unions, community banking, and community development initiatives demonstrates that collective agency can emerge spontaneously or be kindled in poorer communities (Holman, 1998). These can both mitigate the consequences of poverty and sometimes work to lift families out of poverty through the provision of resources.

While the collective actions of people living in poverty may not fall “under the banner of poverty”, as Lister (2004b) put it, there are a number of examples where people have organized around poverty- and income-related issues. For example, Lister (2004a, p.155) cites the birth of the Welfare Rights movement in the United Kingdom in the 1960s as an example of a grassroots movement of people campaigning for rights to social security and against poverty. In the United States, movements like Justice for Janitors, which campaigns for better wages, better health care, and full-time employment, represent a successful model of collective action against shared economic marginalization (Savage, 2006).

Conclusion

Poverty is best conceptualized as the experience of living on a low income. It is a diverse experience structured by geography, duration, social institutions, and demographics but also shaped by the agency of families themselves. While poverty is often measured through families’ incomes, the experience of poverty transcends simple home economics and affects all aspects of their life, from dignity to the ability to maintain life itself.

The geography of poverty matters. Families in poverty in the global south suffer acute deprivations due to a lack of financial resources. They have higher levels of mortality, often from preventable causes, and speak of the soul-crushing burden of living in poverty. In the global north, while the physical consequences of poverty might be different, families speak of similar humiliations, of not being able to participate in the everyday life of their communities and the profound impacts this has on their overall sense of well-being.

The risks of poverty are not shared equally across all families, with institutions and social norms strongly shaping their prospect of poverty. Families with young children and the elderly are more likely to be poor, but to a large extent, this depends on the benefit system of their country and its political willingness to provide a safety net to protect the young and old. Families headed by women are also more likely to be poor, but again, this risk can be shaped by public policy, labor market structures, and gender norms. Families affected by disabilities are also at a higher risk of living below the poverty line, with discrimination and impairments reducing their labor market outcomes.

Poverty often defines the way families live, function, and operate. The art of “getting by” requires meticulous budgeting and balancing family members’ needs. But families are not doomed to forever be “poor”. Most spells in poverty are short-lived and families can and do get out. While work is a common route out for many families, it is not guaranteed; low wage, insecure, and temporary employment all conspire against families in poverty. The extent to which families engage in illicit coping behaviors and what to make of them is debateable. Finally, poverty may be a social issue, attempts to mobile as the “poor” for collective action are rare – however, they are often very successful.

References

- Alcock, P. (2008) Poverty and social exclusion, in The Student’s Companion to Social Policy (eds P. Alcock, M. May, and K. Rowlington), Blackwell Publishing, pp.131–138.

- Atkinson, R. and Bridge, G. (2005) Gentrification in a Global Context: The New Urban Colonialism, Routledge, London.

- Attree, P. (2006) The social costs of child poverty: a systematic review of the qualitative evidence. Children and Society, 20, 54–66.

- Baldwin, M. and Johnson. W. (2006) A critical review of studies of discrimination against workers with disabilities, in Handbook on the Economics of Discrimination (ed. W. Rodgers), Edgar Publishing, Northampton, pp. 119–160.

- Bane, M. and Ellwood, D. (1986) Slipping into and out of poverty: the dynamics of spells. Journal of Human Resources, 21 (1), 1–23.

- Banerjee, A. and Duflo, E. (2007) The economic lives of the poor. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21 (1), 141–167.

- Baulch, B. (1996) The new poverty agenda: a disputed consensus. IDS Bulletin, 27, 1–10.

- Braithwaite, J. and Mont, D. (2009) Disability and poverty: A survey of World Bank poverty assessments and implications. ALTER, European Journal of Disability Research, 3, 219–232.

- Cancian, M. and Meyer, D. (2004) Fathers of children receiving welfare: can they provide more child support? Social Service Review, 78, 179–206.

- CPS (2011) Annual Social and Economic Supplement, Age and Sex of All People, Family Members and Unrelated Individuals Iterated by Income-to-Poverty Ratio and Race (online), http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/cpstables/032011/pov/new01_100.htm (accessed April 20, 2012).

- CSJ (2009) Dynamic Benefits: Towards Welfare the Works, Centre for Social Justice, London.

- Czech Presidency of the European Union (2009) Where We Live – What We Want: The Report of the 8th European Meeting of People Experiencing Poverty, May 15–16, 2009, Brussels (online), http://www.eapn.eu/images/stories/docs/eapn-report-2009-en-web2-light-version.pdf (accessed April 10, 2012).

- Dahl, G. and Lochner, L. (2008) The impact of family income on achievement: evidence from the earned income tax credit. NBER working paper No. 14599, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

- Deepa, N., Patel, R., Schafft, K. et al. (2000) Voices of the Poor: Can Anyone Hear Us? Oxford University Press, New York.

- Department for Education (2007) The Costs of Schooling 2007, DfE, London.

- Dinour. L., Bergen, D., and Yeh, M. (2007) The food insecurity–obesity paradox: a review of the literature and the role food stamps may play. Journal of American Dietetic Association, 107, 1952–1961.

- Dobson, B., Beardsworth, A., Keil, T., and Walker, R. (1995) Diet, Choice and Poverty, Family Policy Studies Centre, London.

- Dowler, E. (1997) Budgeting for food on a low income in the UK: the case of lone-parent families. Food Policy, 22 (5), 405–417.

- Duncan, G. and Brooks-Gunn, J. (1997) Consequences of Growing Up Poor, Russel Sage Foundation, New York.

- Duerr B. (1995) Faces of Poverty: Portraits of Women and Children on Welfare, Oxford University Press, New York.

- DWP (2011) Households Below Average Income (HBAI) (online), http://research.dwp.gov.uk/asd/index.php?page=hbai (accessed February 10, 2012).

- Edin, K. (2001) Hearing on Welfare and Marriage Issues – Testimony Before the Subcommittee on Human Resources of the House Committee on Ways and Means (online), www.gouse.gov/ways_means/humres/107cong/5–22–01/5–22edin.htm (accessed January1, 2002).

- Edin, K., Lein, L., Nelson, T., and Clampet-Lundquest, S. (2000) Talking to low-income fathers. Joint Centre for Poverty Research University of Chicago, Newsletter, 4 (2).

- Ellwood, D. (1988) Poor Support, Basic Books, New York.

- Elwan, A. (1999) Poverty and disability: a survey of the literature. SP discussion paper No. 9932, The World Bank, December 1999.

- Esping-Anderson, G. (1990) Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, Polity Press, Cambridge.

- Eurostat (2012) Income and Living Condition Tables (online), http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/income_social_inclusion_living_conditions/data/main_tables (accessed April 10, 2012).

- Farrell, C. and O’Connor, W. (2003) Low-Income Families and Household Spending: Research Report 192, Department of Work and Pensions, London.

- Fisher, G. (1992) The development and history of poverty thresholds. Social Security Bulletin, 55 (40), 3–14.

- Gordon, D. and Spicker, P. (1999) The International Glossary on Poverty, Zed Books, London.

- Gilliom, J. (2001) Overseers of the Poor, University of Chicago Press, London.

- Glendinning, C. and Millar, J. (1987) Women and Poverty in Britain, Wheatsheaf Books, Brighton.

- Ha, Y., Cancian, M. and Meyer, D.R. (2007) The Regularity of Child Support and Its Contribution to the Regularity of Income. Report to Wisconsin Department of Workforce Development, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison.

- Hamilton, K. (2012) Low-income families and coping through brands: inclusion or stigma? Sociology, 46 (1), 74–90.

- Hernandez, M., Pudney, S. and Hancock, R. (2007) The welfare cost of means-testing: pensioner participation in income support. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 22 (3), 581–598.

- Hipp, R. and Yates, D. (2011) Ghettos, thresholds, and crime: does concentrated poverty really have an accelerating increasing effect on crime? Criminology, 49 (4), 955–990.

- Holman, B. (1998) Faith in the Poor, Lion Publishing, Oxford.

- Holtzer, H. and LaLonde, R.J. (2000) Employment and job stability among less skilled workers, in Finding Jobs: Work and Welfare Reform (eds D.E. Card and R.M. Blank), Russell Sage Foundation, New York.

- IFS (2010) Poverty and Inequality Data Tables (online), www.ifs.org.uk/bns/bn19figs.zip (accessed February 10, 2012).

- Jordan, B. (1996) A Theory of Poverty and Social Exclusion, Polity Press, Cambridge.

- Jenkins, S. (2011) Changing Fortunes: Income Mobility and Poverty Dynamics in Britain, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Kabeer, N. (1995) Reversed Realities; Gender Hierarchies and Development Thought, Verso, London.

- Kempson, E. (1996) Life on a Low Income, York Publishing Services, York.

- Kidd, M., Sloane, P. and Ferko, I. (2000) Disability and the labour market: an analysis of British males. Journal of Health Economics, 19 (6), 961–981.

- Leibman, J. (1999) Lessons About Tax-benefit Integration From the US Earned Income Tax Credit Experience, York Publishing Services, York.

- Lister, R. (2004a) Poverty, Polity Press, London.

- Lister, R. (2004b) No More of “the Poor.” The Guardian (Nov 17).

- Lundberg, S., Pollak, R. and Wales, T. (1997) Do husbands and wives pool their resources? Evidence from the United Kingdom child benefit. Journal of Human Resources, 32 (3), 463–480.

- Luxembourg Income Studies (2012) (online) http://www.lisdatacenter.org/lis-ikf-webapp/app/search-ikf-figures (accessed May 20, 2012).

- Mack, J. and Lansley, S. (1985) Poor Britain, George Allen & Unwin, London.

- McKernan, S. and Ratcliffe, C. (2002) Transition Events in the Dynamics of Poverty, US Department of Health and Human Services, Washington.

- McKernan, S. and Ratcliffe, C. (2005) Events that trigger poverty entries and exits. Social Science Quarterly, 86 (s1), 1146–1169.

- Mead, L. (1993) The New Politics of Poverty: The Nonworking Poor in America, Basic Books, New York.

- Melhuish, E. (2012) The impact of poverty on child development and adult outcomes: the importance of early years education, in Ending Child Poverty by 2012: Progress Made and Lessons Learned (ed. CPAG), CPAG, London.

- Middleton, S., Ashworth, K. and Walker, R. (1994) Family Fortunes, CPAG, London.

- Moore, J. (1989) The end of the line for poverty. Speech to the Greater London Area, CPC, May 11, 1989.

- Murray, C. (1984) Losing Ground: American Social Policy 1950–1980, Basic Books, New York.

- OECD (2010) PISA At a Glance (online), http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/31/28/46660259.pdf (accessed May 25, 2012).

- OECD (2012) OECD.StatExtract (online), http://stats.oecd.org/# (accessed May 25, 2012).

- ONS (2011a) Family Spending, 2011 (online), http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/family-spending/family-spending/family-spending-2011-edition/index.html (accessed May 15, 2012).

- ONS (2011b) Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (online), http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/publications/re-reference-tables.html?edition=tcm%3A77–235202 (accessed May 10, 2012).

- ONS (2012) Families and Households, 2001 to 2011 (online), http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171778_251357.pdf (accessed April 19, 2012).

- Oppenheim, C. and Harker, L. (1996) Poverty: The Facts Revised and Updated, CPAG, London.

- Pahl, J. (1989) Money and Marriage, Macmillan, Basingstoke.

- Piachaud D. (1981) Peter Townsend and the Holy Grail. New Society (Sep 10), pp. 419–421.

- Platt, L. (2005) Discovering Child Poverty: The Creation of a Policy Agenda from 1800 to the Present, Policy Press, Bristol.

- Power, A. and Tunstall, R. (1995) Swimming Against the Tide: Polarisation or Progress on 20 Unpopular Council Estates, Joseph Rowntree Foundation, York.

- Ridge, T. (2002) Childhood Poverty and Social Exclusion: From a Child’s Perspective, The Policy Press, Bristol.

- Ramey, S. and Keltner, B. (2002) Welfare reform and the vulnerability of mothers with intellectual disabilities (mild mental retardation). Focus, 22 (1), 82–86.

- Rank, M. and Hirschl, T. (2001) The occurrence of poverty across the life cycle: evidence from the PSID. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 20 (4), 737–755.

- Rendall, M. and Speare, A. (1995) Elderly poverty alleviation through living with family. Journal of Population Economics, 8 (4), 383–405.

- Rowntree, S. (1901) Poverty: A Study of Town Life, The Policy Press, Bristol.

- Savage, L. (2006) Justice for janitors: scales of organizing and representing workers. Antipode, 38 (3), 645–666.

- Schur, L., Kruse, D., Blasi, J. and Blank, P. (2009) Is disability disabling in all Workplaces? Workplace disparities and corporate culture. Industrial Relations, 48 (3), 381–410.

- Sen, A. (1979) Issues in the measurement of poverty. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 81 (2), 287–307.

- Sen, A. (1981) Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Sen, A. (1985) A sociological approach to the measurement of poverty: a reply to Professor Peter Townsend. Oxford Economic Papers (37), 669–676.

- Smith, A. and Twomey, B. (2002) Labour market experiences of people with disabilities, in ONS Labour Market Trends, pp. 415–427.

- Sorensen, E. and Zibman, C. (2001) Getting to know poor fathers who do not pay child support. Social Service Review, 75, 420–434.

- Stevens, A. (1999) Climbing out of poverty, falling back in: measuring the persistence of poverty over multiple spells. Journal of Human Resources, 34 (9), 557–588.

- Stuber, J. and Kronebusch, K. (2004) Stigma and other determinants of participation in TANF and Medicaid. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 23 (3), 509–530.

- Tai, T. and Treas, J. (2009) Does household composition explain welfare regime poverty risks for older adults and other household members? Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 64B (6), 777–787.

- Townsend, P. (1979) Poverty in the United Kingdom, Allen Lane, Harmondsworth.

- Townsend, P. (1985) A sociological approach to the measurement of poverty: a rejoiner to Professor Amartya Sen. Oxford Economic Papers (37), 659–668.

- UNDP (2011) Fast Facts: Gender Equality and the UNDP (online), http://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/corporate/fast-facts/english/FF-Gender-Equality-and-UNDP.pdf (accessed May 20, 2012).

- UNIFEM (2005) Progress of the World’s Women: Women, Work and Poverty, United Nations Development Fund for Women, New York.

- US Department of Labor Statistics (2010) Highlights of Women’s Earnings in 2009 (online), http://www.bls.gov/cps/cpswom2009.pdf (accessed February 9, 2012).

- Walker, R. (1994) Poverty Dynamics, Avebury, Aldershot.

- Walker, R., Middleton, S. and Thomas, M. (1994) How mothers use child benefit, in Family Fortunes: Pressures on Parents and Children in the 1990s (eds S. Middleton, K. Ashworth, and R. Walker), CPAG, London.

- Walker, R., Ashworth, K., Kellard, K. et al. (1994) “Pretty, pretty, please” just like a parrot: persuasion strategies used by children and young people, in Family Fortunes: Pressures on Parents and Children in the 1990s (eds S. Middleton, K. Ashworth, and R. Walker), CPAG, London.

- Ward-Batts, J. (2008) Out of the wallet and into the purse: using microdata to test income pooling. Journal of Human Resources, 43 (2), 325–351.

- Wheelcock, J. and Jones, K. (2002) “Grandparents are the next best thing”: informal childcare for working parents in urban Britain. Journal of Social Policy, 31 (3), 441–463.

- Wiig, K. and Smith, C. (2009) The art of grocery shopping on a food stamp budget: factors influencing the food choices of low-income women as they try to make ends meet. Public Health Nutrition, 12 (10), 1726–1734.

- Wilson, W. (1997) When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor, Vintage Books, New York.

- World Bank (2006) Malnutrition Prevalence, Weight for age (% of Children under 5) (online), http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.STA.MALN.ZS (accessed May 21, 2012).

- World Bank (2008) Povcal (online), http://iresearch.worldbank.org/PovcalNet/index.htm?1 (accessed May 21, 2012).

- World Health Organisation (2012) Global World Health Observatory Data Repository (online), http://apps.who.int/ghodata/?vid=180# (accessed May 20, 2012).