15

Divorce: Trends, Patterns, Causes, and Consequences

Juho Härkönen

Introduction

The increases in divorce rates have been among the most visible features of the recent decades of family change. Some have seen this as a sign of social and moral disruption with a potential to shatter the family institution and the foundations of society itself. Others have celebrated these trends as signaling increased individual liberty and the loosening of suffocating social mores. Divorce is one of the most often mentioned major life events (Gähler, 1998), and can cause major stress and upheaval for many, and a sense of relief and opportunity for personal growth for others. It is no wonder that divorce and family instability have attracted wide attention among social scientists.

This chapter provides an overview to what is known about divorce, its trends, cross-national variation, predictors, and consequences. Geographically, the focus is on Europe and North America, and the author follows the trend in research and focuses on divorce, that is, the ending of a marital union. In most cases, the event of significance is the end of marital cohabitation. The legal procedures that end the marriage may, in many cases, continue well past the separation of the couple. Other forms of union or marital dissolution, such as permanent separation, desertion, and annulment (marriage declared not valid) have received less research attention.

However, acknowledging the changing family landscape, in which much cohabitation and family life occur outside marriage, a growing number of studies have looked into the dissolution of unmarried cohabitations. There is still active debate on whether, when, and in which countries cohabitation is like marriage, or not (Heuveline and Timberlake, 2004). Many cohabiting unions either split up or are transformed into marriages relatively quickly, even in countries in which cohabitation is common (Jalovaara, 2012). In general, cohabiting unions are less stable than marriages (Andersson, 2002). There are many similarities in the factors that promote or undermine the stability of marriage and cohabitation, as they are in the consequences of their dissolution. However, some important differences can be found which are generally linked to the weaker institutionalization of unmarried cohabitation (Brines and Joyner, 1999).

Furthermore, almost all of the literature has focused on heterosexual couples. Recent years have seen a wave of legal recognition of same-sex partnerships, which has consequently raised scholars’ interest in their demography. But, information concerning the dissolution of same-sex couples remains relatively limited. Research suggests that although same-sex partnerships are in general less stable than heterosexual marriages, the predictors of their instability are in many respects similar (Andersson et al., 2006; Lau, 2012).

Theoretical perspectives on divorce have ranged from macrosociological theories of the role of divorce in the family system to microlevel perspectives on the processes conducive to marital instability (Kitson and Raschke, 1981). Many scholars begin from a least implicit account of divorce in which partners remain in their marriages, as long as the benefits of doing so exceed the sum of the costs of dissolving them and the benefits of other options (Levinger, 1976; Brines and Joyner, 1999). This rationalistic perspective is most explicit in economic approaches to marriage and divorce (Becker, Landes, and Michael, 1977; Becker, 1981). The benefits and costs include emotional rewards, mutual support and commitment, economic and moral considerations, social sanctions and approval, legal issues, children, and new partners. Divorces can be analyzed as events, that is, the decision to leave a partnership and the ending of the marriage. However, they are often preceded by a long process of ending the relationship, which can include estragement from the spouse, stress, conflicts, and even violence (Amato, 2000), and, as mentioned, the legal procedures dissolving the marriage may last well after both spouses consider the marriage ended. Thus, defining and measuring divorce – when it starts and when it ends – can be difficult. Despite the conflicts surrounding many divorces, many seemingly functional marriages end in divorce (Amato and Hohmann-Marriott, 2007), and on the other hand, not all troubled marriages break up. This underlines the heterogeneity of divorces, the importance of factors that act as barriers to divorce or the possible options beyond it, and the need for looking beyond marital quality and satisfaction as determinants. Divorce, in other words, is a multifaceted event (Gähler, 1998).

Trends and Cross-National Differences in Divorce

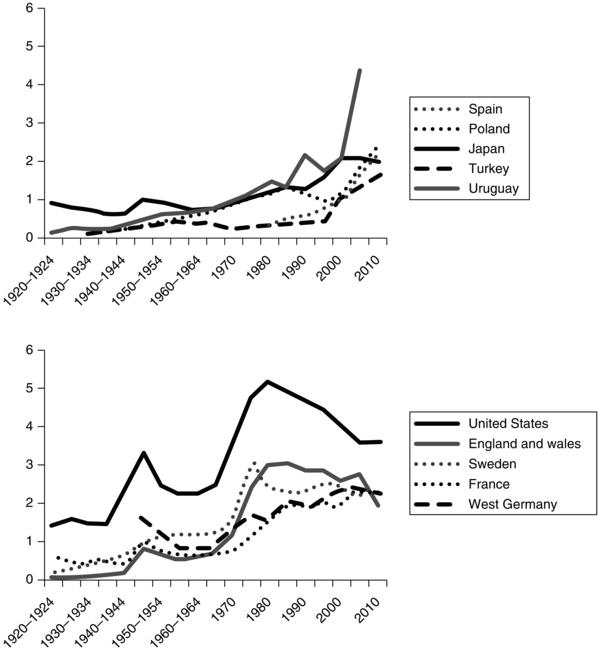

Consider Figure 15.1 which shows the trends in the crude divorce rate for selected countries. Before proceeding to a discussion of these trends, it is important to understand what these numbers tell us. The crude divorce rate shows the number of divorces per 1000 individuals in the population. It is not a perfect measure of underlying marital instability and, particularly, does not tell how many couples eventually divorce (Preston and McDonald, 1979; Schoen and Canudas-Romo, 2006). Crude rates are known to fluctuate over time, and a sudden increase, for example, can indicate that many couples divorce sooner than they otherwise would have. As it is not adjusted for the number of married couples, the crude rate can also be affected by changes in the popularity of marriage. Despite these limitations, the crude divorce rate correlates strongly with better measures (Amato, 2010). It is available for long time periods and for several countries, and is thus suitable for describing long-term cross-national trends.

Figure 15.1 Crude divorce rates in selected countries, 1920–2010.

Divorce rates were higher in all the countries represented in Figure 15.1 at the beginning of the new millennium than just after the First World War. Yet, there are major cross-national differences. The United States has traditionally been a high-divorce society, whereas in Spain, divorce was not possible until 1981. The 1960s saw the beginning of a sharp increase in divorce rates in many countries, but they have stabilized, or even decreased since. In others, such as Spain and Turkey, the increase began later. In Japan, divorce was more common at the beginning of the twentieth century than mid-century (Goode, 1963). Finally, the figure shows temporal fluctuations in the crude divorce rate: it has spiked after the Second World War (Pavalko and Elder, 1990) and after major liberalizations in divorce legislation.

Despite the limitations of the crude divorce rate measure, its overall trend corresponds with the long-term increase in marital instability at the individual level. Approximately, every fifth American marriage contracted in the 1950s had ended in divorce by 25 years after the wedding, whereas about a half of all couples who married in the 1970s or later are expected to divorce (Schoen and Canudas-Romo, 2006; Stevenson and Wolfers, 2007). Increasing numbers of children have experienced the split-up of their parents, and the simultaneous increases in divorce and declines in mortality have meant that family dissolution has replaced parental death as the leading cause for single parenthood (Bygren, Gähler, and Nermo, 2004).

What accounts for these trends and cross-national variations? As a first step in explaining social change, demographers distinguish between cohort effects and period effects. Cohort effects refer to differences between groups of people who shared a critical experience during the same time interval (Alwin and McCammon, 2003). Cohort is often used as a shorthand for birth cohort, but demographers use it in a more general sense. Divorce researchers talk about marriage cohorts when referring to those marrying during the same year. Marriage cohort effects arise when the conditions surrounding the beginning of the marital journey shape couples’ marital expectations and behaviors throughout their marriages (Preston and McDonald, 1979). Cohort effects are responsible for divorce trends to the extent that new marriage cohorts with new attitudes and practices replace earlier ones.

Period effects, in turn, refer to influences which (at least potentially) affect all marriages, regardless of when the couples married; they are something in the air (Cherlin, 1992). They include economic recessions, legal reforms, and cultural trends. Since period effects include not only gradually evolving social trends but also abrupt shifts such as changes in divorce laws, they have more potential to cause sudden increases or decreases in divorce. Divorce researchers generally agree that period effects dominate over cohort effects (Thornton and Rodgers, 1987; Cherlin, 1992; Lyngstad and Jalovaara, 2010). Therefore, to understand divorce trends, we must look into the factors that at least potentially affect all marriages.

The initial increases in divorce took social scientists by surprise (Cherlin, 1992), and even now, there is no single explanation of why divorce rates have increased, or vary cross-nationally. Suggested explanations range from economic trends to cultural shifts and legal changes. Many explanations point to the change in gender roles – from gender asymmetry to increasing gender symmetry and equality – and, in particular, to the dramatic increases in married women’s labor market activity. Indeed, the trends in female employment and in divorce rates have closely followed one another (Cherlin, 1992; Ruggles, 1997), and a positive relationship between the two is also visible across countries (Kalmijn, 2007). Most researchers have interpreted the causality to run from female employment to divorce. A problem with this interpretation is that, as will be discussed in the next section, the microlevel evidence regarding this link is not conclusive (Özcan and Breen, 2012). Other economic explanations have focused on the relative deterioration of men’s economic fortunes in many countries, but neither of these can explain the big picture (Stevenson and Wolfers, 2007).

Other theories emphasize cultural changes (Lesthaeghe, 1995; Coontz, 2005; Cherlin, 2009). A popular account is provided by the second demographic transition thesis (Lesthaeghe, 1995), which links the changes in family behavior to the increases in individualism and other postmaterial values. There has been a shift in family attitudes toward more gender equality, personal fulfillment, and acceptance of nontraditional family behaviors such as divorce (Thornton and Young-De Marco, 2001). This shift has been very uneven across the Western world and major cross-national variation in the acceptance of divorce remains (Gelissen, 2003).

These new ideas fit squarely with the traditional views of marriage and family life, which were based on rigid roles and sharp gender inequalities, and emphasized the married couple as a single unit, rather than a partnership of two individuals (Coontz, 2005). However, as with explanations having to do with attitudes more generally, there is a chicken-and-egg problem of which came first, attitudes or behavior? Divorce attitudes often seemed to adjust to changing realities, instead of providing the initial push to increased divorce (even though liberalized attitudes may have made later divorces easier and more common) (Cherlin, 1992). More generally, testing these explanations is often difficult and constrained by the availability of relevant cross-national data over long periods of time. Some scholars have used religiosity as a measure of cultural acceptance of divorce and found secularization to correlate positively with divorce rates (Kalmijn, 2010). In an interesting study in Brazil, Chong and La Ferrera (2009) found that the spread of telenovelas in that country was followed by increases in divorce, presumably as couples became increasingly exposed to new ideas about family life. Even though the explanatory power of cultural influences on divorce is difficult to assess, the spread of new ideas and attitudes is likely to have contributed to the increases in family instability.

Divorce laws have changed markedly through the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first century. Divorce was prohibited until recently in several Western countries (e.g., Italy legalized divorce in 1974, Spain in 1981, Ireland in 1997, and Malta in 2011), and is still difficult to obtain in others. Often, divorces could be granted on the basis of serious faults (such as adultery, violence, or mental illness), or possibly, by the mutual consent of the spouses (Härkönen and Dronkers, 2006). Even then, the process was usually expensive and lengthy. Major liberalization of divorce laws began during the 1960s and 1970s, and in 1970, California was the first US state to implement unilateral ‘no fault’ divorce, in which either spouse could exit the marriage without having to provide specific reasons. Sweden followed suit in 1974, and by the turn of the millennium, most Western countries had liberalized their divorce legislation (Gonzalez and Viitanen, 2009).

Do these legislative changes affect divorce rates, or do they merely reflect the rising acceptance of and demand for divorce? Recent research has generally concluded that liberalization of divorce laws did cause short-term spikes in divorce rates (see, e.g., Sweden in 1974 in Figure 15.1), presumably as spouses in ill-functioning marriages took advantage of the better opportunities for exiting their marriages (Wolfers, 2006; Stevenson and Wolfers, 2007; González and Viitanen, 2009). According to many, these effects were not lasting, and the long-term effect of the liberalization of divorce laws was, at most, a small increase in divorce rates (however, see González and Viitanen, 2009). Loosening of official control over marriages and divorces did, however, change the divorce process and the dynamics of marriages. Unilateral divorce – the possibility of exiting a marriage without the consent of one’s spouse – shifted the power balance to the spouse more willing to exit, while the shortening of the legal process and the weakening need to show fault or irreconcilability have made divorce processes faster and possibly less conflict-ridden (Stevenson and Wolfers, 2007).

All in all, social scientists have had difficulties in explaining the increases in divorce. All available explanations have limitations. An interpretation of the trends is that values have changed and reorientations provide the social opportunities and subjective motives for divorce, whereas increases in women’s economic independence have been among the factors providing the means for doing so (Cherlin, 2009). Together, these changes meant that people were more ready, willing, and able to divorce (Coale, 1973; Sandström, 2012).

If social scientists were unable to foresee an increase in divorce, they were equally unable to predict the recent stabilization of marriages in many countries. These developments – see Figure 15.1 – are not merely due to the limitations of crude divorce measures. There has been a corresponding leveling and even decrease in underlying marital instability. This has been clear in the United States since the 1980s (Goldstein, 1999; Schoen and Canudas-Romo, 2006; Stevenson and Wolfers, 2007), and also found in other countries, such as Sweden (Andersson and Kolk, 2011). Marriages, of course, must take place for there to be divorce, and thus many scholars have looked at the characteristics of marrying couples for clues regarding recent stabilization in divorce rates. One of the issues here has been the increase in the age at marriage. As will be discussed later, older age at marriage is associated with lower divorce risk, and this has been found to contribute to the stabilization of marriage in the United States (Heaton, 2002). Increases in educational levels are another contributing factor. Additionally, increases in nonmarital cohabitations (which are more likely to dissolve) can mask the overall instability of couple relationships (Raley and Bumpass, 2003).

Who Divorces? The Predictors of Divorce

Earlier in this chapter, I discussed findings regarding trends in divorce over time and cross-national variation in divorce rates. Divorce trends were seen to be primarily caused by period effects, by something that is in the air as Andrew Cherlin (1992, p. 31) has described it. However, just as everyone does not get rich during an economic boom or does not get the flu during an epidemic, not all marriages end in divorce, and there are systematic differences in which do and which do not.

When asked why Mrs. and Mr. Jones divorced, many would give reasons such as growing apart; they were never suited to each other; they were always arguing; or perhaps infidelity. A large body of research has investigated the proximate and psychological factors that may lead to divorce (Bradbury, Finchman, and Beach, 2000). Unsurprisingly, low marital satisfaction is a strong predictor of divorce and infidelity, while incompatibility, and behavioral and relationship problems rank high among the reasons people give for their divorces (Amato and Rogers, 1997; Amato and Previti, 2003; De Graaf and Kalmijn, 2006). Interestingly, De Graaf and Kalmijn (2006) observed that in the Netherlands, strong reasons for divorce, such as infidelity or violence, have become less often cited, whereas psychological and relational problems, and reasons to do with the division of housework, have increased in importance. These findings are in line with ideas of marital change toward a partnership between equal individuals respecting their personal needs (Coontz, 2005; Cherlin, 2009). Despite its interest, the author does not discuss further the psychological literature on divorce, but instead turns to the importance of more sociological factors.

We know a good deal about the socioeconomic and demographic predictors of divorce (for recent reviews, see Amato, 2000, 2010; Amato and James, 2010; Lyngstad and Jalovaara, 2010). Even though the strength of the different predictors may vary from one country and time period to the next (Wagner and Weiß, 2006), many point in similar directions, regardless of the context (Amato and James, 2010; Lyngstad and Jalovaara, 2010).

Whether a couple divorces or not is related to the life-course stages and prior experiences of the partners. Young couples, for instance, have been consistently shown to have higher divorce rates due to their lower (psychological and socioeconomic) maturity, potentially unreasonable expectations, and a shorter search that led to making an unstable match or overlooking better outside options (alternative partners) (Booth and Edwards, 1985; Lyngstad and Jalovaara, 2010).

Having been previously married also predicts divorce, and generally, the more prior partnerships one has accumulated, the higher the divorce risk is (Castro Martin and Bumpass, 1989; Teachman, 2008). This finding has been commonly explained by selection into further marriage: one has to divorce before marrying for the second time, and those who divorced once would be more likely to do it again (Poortman and Lyngstad, 2007). A similar selection explanation has been used to explain why couples who cohabited before marrying are more likely to divorce, even though one might expect the opposite, given that such couples have more experience and information about each other and life together (Axinn and Thorton, 1992; Amato, 2010; Lyngstad and Jalovaara, 2010). According to this explanation, couples who cohabited are less traditional and may have different ideals and expectations of marriage. Some scholars, however, have proposed that experience of cohabitation may actually increase divorce risk by undermining the commitment to marriage as the context for sexual relationships and childbearing (Thomson and Collella, 1992), or through relationship inertia by which relatively incompatible cohabiting couples drift into marriage, as the barriers to ending the relationship accumulate (e.g., shared possessions and, possibly, children) (Stanley, Rhoades, and Markman, 2006).

Divorce risk is not constant through the course of marriage. While few marriages dissolve soon after the wedding, the likelihood of it happening increases through the first years. Marital satisfaction generally declines over the course of marital life (Umberson et al., 2005), and couples have the highest risk of divorcing between the fourth and the seventh year after the wedding. After this, divorce risk begins to decline gradually as couples accumulate investments in their marriage which increase the barriers for leaving it (Lyngstad and Jalovaara, 2010).

One such barrier is children. Theoretically, children can be regarded as shared investments (Becker, Landes, and Michael, 1977; Brines and Joyner, 1999), and parents can forgo, or at least postpone their divorce, if they are concerned with its adverse effects on their children. Indeed, couples with children, especially small ones, have lower divorce risks than childless couples (Lyngstad and Jalovaara, 2010). Again, this may reflect the characteristics of the couples who do not have children, as they might have lower trust in their marriages to begin with. Whether having children actually stabilizes marriages seems, on the other hand, to depend on the country and the time period (Lyngstad and Jalovaara, 2010). Some research even suggests that having boys can have a stronger stabilizing effect (Morgan, Lye, and Condran, 1988), presumably due to fathers’ increased involvement in childcare. However, this finding remains contested. Having children can also destabilize marriages if it means less time for fostering the relationship (Twenge, Campbell, and Foster, 2004), which, as discussed, has become increasingly important in modern marriages.

Socioeconomic factors related to divorce have been widely discussed in the literature. The starting point for practically all research is that husbands’ and wives’ socioeconomic resources have different influences. This assumption is often based on an economic approach to family life, which sees economic resources as an exchange for unpaid domestic work and in which husbands’ and wives’ roles are complementary (Becker, Landes, and Michael, 1977; Becker, 1981). In practice, this perspective predicts that mens’ socioeconomic resources – such as education, employment, and earnings – stabilize marriages, whereas wives’ resources destabilize them. While this prediction has found general support in research in regard to men’s resources (Lyngstad and Jalovaara, 2010), findings are less consistent when it comes to the influence of wives’ resources. The relationship between female education and marital stability is a case in point. In the United States, women with higher levels of education have had lower rates of divorce for a long time and this gap has grown (Martin, 2006). In many other countries, highly educated women used to have higher divorce rates. But, over time, less educated women have seen their divorce risks increase at a faster rate, and currently, they are as, or more, likely to divorce in several countries (Härkönen and Dronkers, 2006). These developments are in line with the Goode hypothesis, which maintains that the initially high social, legal, and economic barriers to divorce kept it the privilege of those with high enough resources to overcome them (Goode, 1962). As these barriers have declined, divorce has become accessible to those with fewer resources, who are often those under more economic and other marital stress. Similar discrepancies can be seen in the research on female employment and marital instability (Amato, 2010; Amato and James, 2010; Lyngstad and Jalovaara, 2010; Özcan and Breen, 2012). Earlier predictions were that female employment would destabilize marriages, as it weakened the benefits from a household division of labor (Becker, Landes, and Michael, 1977; Becker, 1981), improved opportunities for maintaining independent households (England and Farkas, 1986), and increased the chances to meet new partners (South and Lloyd, 1995). Many empirical findings supported this.

Predictions of the destabilizing effect of female employment and earnings have, however, been increasingly questioned. Many have argued that female employment can stabilize partnerships by strengthening families’ economic security and balancing the spouses’ roles and responsibilities (Oppenheimer, 1997). Others claimed that the expectation of divorce may actually lead to increases in wives’ employment, rather than the opposite (Özcan and Breen, 2012). Furthermore, wives’ employment and earnings may help them exit dysfunctional marriages rather than destabilizing all marriages (Sayer and Bianchi, 2000; Sayer et al., 2011), or have destabilizing effects only if they do not adhere to the values of the couple (Amato et al., 2007) or the surrounding society (Cooke, 2006). An additional modifier of these effects is public policy. Female employment can stabilize marriages in countries with policies that support work–family balance (Cooke et al., Forthcoming). Overall, then, the effects of female economic activity are much more contingent than previously thought.

Women, however, have practically always and everywhere been more likely to file for divorce and start the process leading to divorce. This remarkably stable finding seems to be found for every society where such statistics exist, Western and non-Western alike (Mignot, 2009). Exceptions have been during major wars and their aftermaths. Many findings furthermore suggest that women’s divorce filings are more closely related to socioeconomic factors (Kalmijn and Poortman, 2006; Sayer et al., 2011; Boertien, 2012), and women are more likely to name relational and psychological motives for their divorces (De Graaf and Kalmijn, 2006). Men, on the other hand, appear less likely to initiate divorce when the couple has young children (Kalmijn and Poortman, 2006; Hewitt, 2009), possibly reflecting an anticipation of weaker postdivorce contact with their children.

Increases in international migration have spurred interest into the family lives of migrant groups. Migration as a major life event can itself have a divorce-inducing effect, especially since one of the spouses may benefit from the move more than the other (Lyngstad and Jalovaara, 2010). Migrant groups can find themselves landing in a society in which marital mores and divorce rates differ noticeably from those in their country of origin. In particular, much of the migration flows to the Western countries are from societies with less divorce, and exposure to the new environment can entail increases in divorce rates of these groups (Landale and Ogena, 1995; Qureshi, Charsley, and Shaw, 2012). At the same time, these groups may keep features of their countries of origin, and in general, one finds major differences in marital stability between different groups (Kalmijn, 2011; Qureshi, Charsley, and Shaw, 2012). Increased immigration has led to an increase in the number and share of marriages between migrant groups and the native population, and between migrant groups themselves. While intermarriage is commonly regarded as a sign of integration, such exogamous marriages face higher dissolution rates; the further apart the spouses are culturally, the higher the dissolution rates are (Dribe and Lundh, 2012).

Consequences of Divorce

One of the main concerns with the increase in divorce has been its effects on the well-being of children and adults. These questions have aroused major interest among social and psychological scientists, and many conclusions have been remarkably conflicting (McLanahan and Sandefur, 1994; Cherlin, 1999). What can we say about the effects of divorce and family dissolution on adults and children?

Most studies conclude that divorced adults and their children fare worse according to several indicators of psychological, physical, and socioeconomic well-being, compared to those who did not experience divorce (Amato, 2000, 2010; Garriga and Härkönen, 2009; Amato and James, 2010). Findings of these effects range from heightened poverty levels (Callens and Croux, 2009) and lower educational performance of the children of divorce (Garriga and Härkönen, 2009; Amato and James, 2010) to increased occurrence of psychological distress (Amato and Keith, 1991) and many physical health conditions (Amato and James, 2010).

Does the experience of divorce itself cause these differences? Couples who break up differ from those remaining together in many respects. They are generally less happy and often more conflictual, and they also differ in terms of socioeconomic resources and many demographic characteristics. All these can themselves affect well-being, and divorcing couples and their children might have fared worse even without the divorce. Indeed, those who remain in unhappy marriages fare worse in terms of life satisfaction than those who dissolved their unhappy marriages (Hawkins and Booth, 2005).

Since the golden tool for addressing causality – the randomized experiment – is for obvious reasons out of the question when assessing the effects of divorce, researchers are left to various second-best alternatives. Furthermore, since divorce is not simply a snapshot event but rather a (potentially long-lasting) process, it can be conceptually challenging even to separate divorce effects (i.e., divorce-as-event-effects) from the effects of the preceding process (Amato, 2000, 2010), as discussed in the Introduction section.

Despite the difficulties, several scholars have used various sophisticated methods to assess this issue. A common conclusion is that divorce can indeed affect the well-being and performance of adults and children alike, even though the effects are neither necessarily large nor long-lasting, and tend to show a great deal of heterogeneity (Amato, 2000, 2010; Garriga and Härkönen, 2009).

Take the example of the effects on the well-being of adults. Despite the sadness, upset, and feelings of loss associated with divorce, it can also be a relief to at least one of the partners, often for the one who has most wanted to separate (Wang and Amato, 2004). In many instances, psychological well-being tends to decrease already years prior to the divorce itself, stressing the processual nature of marital dissolution (Mastekaasa, 1994; Amato, 2000). In general, the adjustment of divorced persons shows major variation, with some individuals managing to adjust to the new situation relatively fast, while for others, divorce represents a long-term chronic problem from which they might never fully recover (Amato, 2000, 2010; Amato and James, 2010).

Whether divorce leads to declines in well-being depends on the nature of the marriage which the partners are leaving. Divorced persons who end a high-conflict marriage often experience less decline and even an increase in well-being, whereas those whose marriage was characterized by low conflict and relatively high satisfaction often experience more loss in well-being (Kalmijn and Monden, 2006; Amato and Hohmann-Marriott, 2007). Furthermore, adjustment to divorce depends on various socioeconomic and interpersonal resources, such as employment, income, social support, and whether one has a new partner (Gähler, 1998; Wang and Amato, 2004). It also depends on the broader societal context, and divorce effects are weaker in countries in which family support is stronger and in which divorce is more common (Kalmijn, 2010). Finally, there are no consistent gender differences in the subjective well-being consequences of divorce (even though men seem to suffer greater physical health declines) (Amato and James, 2010).

Divorce can have important economic consequences, especially for women (DiPrete and McManus, 2000; McManus and DiPrete, 2001; Uunk, 2004). Economic dependency in the marriage tends to lead to larger economic losses following divorce, whereas the sole or main economic providers may even gain economically (McManus and DiPrete, 2001). On the other hand, welfare state arrangements that provide income and support the employment of divorced mothers ameliorate the negative economic consequences of family dissolution (DiPrete and McManus, 2000; Uunk, 2004). Despite the variation in the economic consequences of divorce, it is among the main life events that can lead to poverty (Callens and Croux, 2009).

There has been even more concern on the effects of family dissolution on children. Over time, views have ranged from assumptions of major long-term negative effects on children’s emotional and socioeconomic well-being to claims of no effects at all (McLanahan and Sandefur, 1994; Cherlin, 1999). Empirical findings support neither view. Children of divorce generally fare worse in terms of emotional and educational outcomes, but the effects are, on average, small or modest (Amato and Keith, 1991; Amato and Booth, 1997; Cherlin, 1999; Amato, 2000, 2010; Garriga and Härkönen, 2009; Amato and James, 2010).

These negative outcomes are already present some while before the parental divorce (Cherlin et al., 1991; Sanz-de-Galdeano and Vuri, 2007; Kim, 2011), underlining the earlier-mentioned difficulty in separating the effects of divorce from the processes leading to it. Growing up in a high-conflict family can in itself have negative effects on children’s well-being and socioeconomic outcomes, and in such cases, parental divorce may actually have positive effects (Amato, Loomis, and Booth, 1995; Amato and Booth, 1997; Cherlin, 1999; Dronkers, 1999; Booth and Amato, 2004). However, children whose parents ended a low-conflict marriage fare generally worse than those whose parents remained together. The effects of parental divorce on children’s outcomes thus vary in the same ways as the effects on divorcing adults, and small or modest average effects hide considerable underlying variation.

The effects of parental divorce depend on the immediate economic consequences and the general instability surrounding family dissolutions, which can have repercussions particularly on academic achievement (McLanahan and Sandefur, 1994; Thomson, Hanson, and McLanahan, 1994; Amato, 2000). Major drops in economic well-being, frequent residential moves, changes in the social environment, and other instability-generating factors have the potential to undermine children’s outcomes. Some similar effects have been found for parental repartnering, which often can lead to new separations (Amato, 2010; Sweeney, 2010). Economic resources do not explain all of the effects of parental divorce, and psychological and relationship factors play an important role in explaining the effects of parental divorce. The adjustment of the parents themselves and their parenting practices during and after the divorce process contribute to the adjustment of their children, as does the overall quality of the relationships the children maintain with both of their parents. For these reasons, parental divorce can affect child outcomes even in well-developed welfare states (Gähler, 1998; Garriga and Härkönen, 2009; Amato and James, 2010).

Parental divorce often causes increased levels of anxiety during the divorce process, which can be exacerbated by the stress it lays on parents and their capability to engage in effective parenting. For many children, however, these effects are relatively short-lived, as many adjust to the new situation reasonably well over time (Amato and Keith, 1991; Cherlin, 1999; Amato, 2000, 2010; Pryor and Rodgers, 2001). For others, it may present a source of more chronic strain from which they never fully recover. One of the avenues through which parental divorce can have long-term effects on children’s life courses is through educational attainment. If parental divorce disturbs the child’s educational career – for example, through affecting their economic or psychological well-being or relationships with his/her parents, teachers, or friends – this disturbance may translate into lower levels of socioeconomic attainment and physical and psychological well-being in adulthood (Garriga and Härkönen, 2009; Amato and James, 2010).

Another long-term effect of parental divorce concerns the family life experiences of the children themselves. A well-documented finding is the intergenerational transmission of divorce: children of divorce are more prone to divorce themselves, as they may lack interpersonal skills that are conducive to marital stability or are more likely to perceive divorce as a viable solution to marital problems (Wolfinger, 2005; Dronkers and Härkönen, 2008). Parental divorce can also weaken contacts between children, their parents, and their grandparents (Aquilino, 1994; Garriga and Härkönen, 2009; Albertini and Garriga, 2011). These negative effects are particularly likely for the relationships between children and their fathers and the fathers’ kin. This is not surprising, given the still-prevalent custody arrangements and women’s role as kin-keepers. Finally, even if parental divorce generally has weak long-term effects on clinical indicators of psycho-emotional well-being, such as depression and anxiety disorders, many children of divorce still experience feelings of sadness and loss, even long after the parental separation (Amato, 2010).

One might expect that the effects of parental divorce have weakened as divorce rates have increased, its stigma decreased, and parents and societies have developed strategies to cope with its consequences. Maybe surprisingly, there is no strong evidence to support this belief (Ely et al., 1999; Amato, 2001; Garriga and Härkönen, 2009). However, one noticeable change in children’s postdivorce conditions concerns their custody arrangements. In many countries, legal and practical joint custody arrangements have become more common, and in some cases even the norm. The limited number of studies on the topic does not permit strong conclusions, but existing findings suggest that joint custody can have positive effects on several well-being outcomes. Increasing joint custody can also weaken the negative effects of divorce on father–child relationships (Bauserman, 2002; Bjarnarson and Arnarsson, 2011).

Summing up, divorce has the potential to cause major disruption in the lives of adults and children, and the effects can be long-lasting. However, not everyone experiences long-lasting negative effects; most people adjust well over time, and for some, divorce may be beneficial (Cherlin, 1999; Amato, 2000). Regarding children’s adjustment, Amato and James (2010, p. 9) summarized that “children function reasonably well after divorce if their standard of living does not decline dramatically, their resident mothers are psychologically well adjusted and engage in high-quality parenting, they maintain close ties to fathers, and their parents avoid conflict and engage in at least a minimal level of cooperation in the postdivorce years.”

The discussion thus far has concerned effects of divorce on those individuals who experience it. Rising divorce rates can also affect those who did not experience divorce: living in a high-divorce (risk) society may itself affect behavior and well-being. Lower obstacles for leaving partnerships improve the chances of doing so and can empower partners – especially the weaker partner – to bargain for a better deal. Liberalization of divorce laws (the adoption of unilateral divorce) has decreased rates of female suicide, domestic violence, and women murdered by their spouses (Stevenson and Wolfers, 2006). These new laws gave partners, and women especially, the chance to improve their relationship or optionally leave a potentially disruptive (and even lethal) one. Facing the prospect of divorce can encourage partners to protect against its consequences, for example, by improving one’s position in the labor market (Özcan and Breen, 2012) or by saving more (Gonzalez and Özcan, 2008). Children may also be affected. Those who grew up under a liberal divorce regime had weaker well-being outcomes according to various indicators (Gruber, 2004), and children exposed to peers with divorced parents have been found to fare poorer in school (Pong, Dronkers, and Hampden-Thomson, 2003).

Discussion

Divorce rates have increased among Western countries and beyond during the last decades, and these trends are considered key components of family change. Yet, these developments have been uneven and occurred at different times in different countries; furthermore, in many countries, divorce rates have stabilized and even decreased in more recent years. Divorce has become a part of the family institution and a realistic possibility, which spouses need to take into consideration when marrying. Though less stigmatized than before, divorce can still cause major distress and disruption to the adults and children who experience it. The possibility of experiencing divorce, and contact with people who have, can in themselves shape behaviors and experiences.

What will the future look like? As discussed earlier, the initial increases in divorce rates took many social scientists by surprise, as have the recent trends toward marital stability in some countries. Therefore, it is clearly difficult to foresee in which countries divorce rates will continue to increase and in which marriages will become more stable. The increases in unmarried cohabitation pose another challenge, as divorce rates have become an ever weaker indicator of couple relationship instability. Despite some indications that the retreat from marriage may have stalled in some of the countries where it started first (Ohlsson-Wijk, 2011), it seems unlikely that marriage will recover the same centrality in family life as it had in the previous decades.

Overall, there are considerable uncertainties in attempts to predict future rates of divorce and couple relationship instability. To the extent that the increases in divorce and instability reflected incompatibilities between prevailing family institutions and changing society, it is possible that divorce rates will stabilize and decline if social practices and institutions adapt to the changing circumstances. Such declines in divorce have occurred before. As briefly mentioned earlier, divorce in Japan was more common at the beginning of the twentieth century than some decades later, which was interpreted as reflecting adaptation of family life to broader societal changes (Goode, 1963). In the Western countries, an important candidate for change is gender roles. The changes in gender roles were to a large extent driven by changes in women’s roles and activities, whereas men have been much slower in taking up what were previously female tasks. An increase in men’s willingness to do their share in the household may thus lead to increased family stability, as this would fit better with the increasingly prevailing egalitarian ideals of partnerships and marriage as a union of two equals with their individual needs (cf. Esping-Andersen and Billari, 2012). However, even if rates of divorce and family instability were to decline, it is likely that the previous era of stable marriages and nuclear families will not return in the near future.

Can policies affect family instability and help adults and children who experience it adjust to it better? Earlier, it was pointed out that many of the findings regarding the effects of divorce legislation on divorce do not suggest that such laws have major long-term effects on divorce rates. Thus, a shift toward stricter regulation of marriages may not have the desired effect, especially since much of modern family life occurs outside the institution of marriage. How effective can policies be in helping adults and children adjust successfully to the divorce experience? Many traditional social policies, such as income transfers and policies aimed at helping (single) mothers find and keep employment, can be effective in combating the financial consequences of divorce, which are generally reduced in the generous welfare states such as the Nordic countries (Uunk, 2004). This can itself be an important policy goal and help divorced persons and their children adjust by decreasing the importance of one of the stressors which often follow divorce. However, they may not be enough, as many of the influences of divorce function through psychological stressors and their effects on parenting and other social relationships. To target these factors, counseling programs aimed at easing such stressors and helping with parenting can be effective (Pryor and Rodgers, 2001).

References

- Albertini, M. and Garriga, A. (2011) The effect of divorce on parent-child contacts: evidence on two declining effect hypotheses. European Societies, 13 (2), 257–278.

- Alwin, D.F. and McCammon, R.J. (2003) Generations, cohorts, and social change, in Handbook of the Life Course (eds. J.T. Mortimer and M.J. Shanahan), Springer, New York, pp. 23–50.

- Amato, P.R. (2000) The consequences of divorce for adults and children. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62 (6), 1269–1287.

- Amato, P.R. (2001) Children of divorce in the 1990s: an update of the Amato-Keith (1991) meta-analysis. Journal of Family Psychology, 15 (3), 355–370.

- Amato, P.R. (2010) Research on divorce: continuing developments and new trends. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72 (3), 650–666.

- Amato, P.R. and Keith, B. (1991) Parental divorce and the well-being of children: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 110 (1), 26–46.

- Amato, P.R. and Booth, A. (1997) A Generation at Risk: Growing Up in an Era of Family Upheaval, Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

- Amato, P.R. and Rogers, S.J. (1997) A longitudinal study of marital problems and subsequent divorce. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 59 (3), 612–624.

- Amato, P.R. and Previti, D. (2003) People’s reasons for divorcing: gender, social class, the life course, and adjustment. Journal of Family Issues, 24 (5), 602–626.

- Amato, P.R. and Hohmann-Marriott, B. (2007) A comparison of high- and low-distress marriages that end in divorce. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69 (3), 621–638.

- Amato, P.R. and James, S. (2010) Divorce in Europe and the United States: commonalities and differences across nations. Family Science, 1 (1), 2–13.

- Amato, P.R., Loomis, L.S. and Booth, A. (1995) Parental divorce, marital conflict, and offspring well-being during early adulthood. Social Forces, 73 (3), 895–915.

- Amato, P.R., Booth, A., Johnson, D.R. and Rogers, S.J. (2007) Alone Together: How Marriage in America is Changing, Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

- Andersson, G. (2002) Dissolution of unions in Europe: a comparative overview. Zeitschrift für Bevölkerungswissenschaft, 27, 493–504.

- Andersson, G. and Kolk, M. (2011) Trends in childbearing and nuptiality in Sweden: an update with data up to 2007. Finnish Yearbook of Population Research, XLVI, 21–29.

- Andersson, G., Noack, T., Seierstad, A. and Weedon-Fekjær, H. (2006) The demographics of same-sex marriages in Norway and Sweden. Demography, 43 (1), 79–98.

- Aquilino, W.S. (1994) Later life parental divorce and widowhood: impact on young adults’ assessment of parent-child relations. Journal of Marriage and Family, 56 (4), 908–922.

- Axinn, W.G. and Thornton, A. (1992) The relationship between cohabitation and divorce – selectivity or causal influence. Demography, 29 (3), 357–374.

- Bauserman, R. (2002) Child adjustment in joint-custody versus sole-custody arrangements: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Family Psychology, 16 (1), 91–101.

- Becker, G.S. (1981) A Treatise on the Family, Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

- Becker, G.S., Landes, E.M. and Michael, R.T. (1977) An economic analysis of marital instability. Journal of Political Economy, 85 (6), 1141–1187.

- Bjarnarson, T. and Arnarsson, A.M. (2011) Joint physical custody and communication with parents: a cross-national study of children in 36 Western countries. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 42, 871–890.

- Boertien, D. (2012) Jackpot? Gender difference in the effects of lottery wins on separation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74 (5), 1038–1053.

- Booth, A. and Edwards, J.N. (1985) Age at marriage and marital instability. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 47 (1), 67–75.

- Booth, A. and Amato, P.R. (2004) Parental predivorce relations and offspring postdivorce wellbeing. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 63 (1), 197–212.

- Bradbury, T.N., Finchman, F.D. and Beach, S.R.H. (2000) Research on the nature and determinants of marital satisfaction: a decade in review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62 (4), 964–980.

- Brines, J. and Joyner, K. (1999) The ties that bind: principles of cohesion in cohabitation and marriage. American Sociological Review, 64 (3), 333–355.

- Bygren, M., Gähler, M. and Nermo, M. (2004) Familj och arbete – vardagsliv i förändring, in Familj och Arbete – Vardagsliv i Förändring (eds. M. Bygren, M. Gähler and M. Nermo), SNS Förlag, Stockholm, pp. 11–55.

- Callens, M. and Croux, C. (2009) Poverty dynamics in Europe: a multilevel recurrent discrete-time hazard analysis. International Sociology, 24 (3), 368–396.

- Castro Martin, T. and Bumpass, L.L. (1989) Recent trends in marital disruption. Demography, 26 (1), 37–51.

- Cherlin, A.J. (1992) Marriage, Divorce, Remarriage, 2nd edn, Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

- Cherlin, A.J. (1999) Going to extremes: family change, children’s well-being, and social science. Demography, 36 (4), 421–428.

- Cherlin, A.J. (2009) The Marriage-Go-Round. The State of Marriage and Family in America Today, Knopf, New York.

- Cherlin, A.J., Furstenberg, F.F., Jr., Chase-Lindsale, L. et al. (1991) Longitudinal studies of the effects of divorce on children in Great Britain and the United States. Science, 525 (5011), 1386–1389.

- Chong, A. and La Ferrera, E. (2009) Television and divorce: evidence from Brazilian novelas. Journal of the European Economic Association, 7 (2–3), 458–468.

- Coale, A. (1973) The demographic transition reconsidered, in International Population Conference: Liége 1973 – Congres International de la Population: Liége 1973, vol. 1, IUSSP, Liége.

- Cooke, L.P. (2006) “Doing” gender in context: household bargaining and the risk of divorce in Germany and the United States. American Journal of Sociology, 112 (2), 442–472.

- Cooke, L.P., with Erola, J., Evertsson, M. et al. (forthcoming) Labor and love: wives’ employment and divorce risk in its sociopolitical context. Social Politics

- Coontz, S. (2005) A History of Marriage: From Obedience to Intimacy, or How Love Conquered Marriage, Viking, New York.

- De Graaf, P.M. and Kalmijn, M. (2006) Divorce motives in a period of rising divorce: evidence from a Dutch life-history survey. Journal of Family Issues, 27 (4), 483–505.

- DiPrete, T.A. and McManus, P.A. (2000) Family change, employment transitions, and the welfare state: household income dynamics in the United States and Germany. American Sociological Review, 65 (3), 343–370.

- Dribe, M. and Lundh, C. (2012) Intermarriage, value context and union dissolution: Sweden 1990–2005. European Journal of Population, 28, 139–158.

- Dronkers, J. (1999) The effects of parental conflicts and divorce on the well-being of pupils in Dutch secondary education. European Sociological Review, 15 (2), 195–212.

- Dronkers, J. and Härkönen, J. (2008) The intergenerational transmission of divorce in cross-national perspective: results from Fertility and Families Surveys. Population Studies, 62 (3), 273–288.

- Ely, M., Richards, M., Wadsworth, M. and Elliott, B.J. (1999) Secular changes in the association of parental divorce and children’s educational attainment – evidence from three British cohorts. Journal of Social Policy, 28 (3), 437–455.

- England, P.G.F. (1986) Households, Employment and Gender: A Social, Economic and Demographic View, Aldine, Hawthorne.

- Esping-Andersen, G. and Billari, F. (2012) Demographic theory revisited. Working paper, Pompeu Fabra University and University of Oxford.

- Gähler, M. (1998) Life After Divorce: Economic, Social and Psychological Well-Being Among Swedish Adults and Children Following Family Dissolution. Swedish Institute for Social Research Reports No 32, Swedish Institute for Social Research, Stockholm.

- Garriga, A. and Härkönen, J. (2009) The Effects of Marital Instability on Children’s Well-Being and Intergenerational Relations. EQUALSOC state-of-the-art report. Universitat Pompeu Fabra and Stockholm University.

- Gelissen, J. (2003) Cross-national differences in public consent to divorce: Effects of cultural, structural, and compositional factors, in The Cultural Diversity of European Unity: Findings, Explanations and Reflections from the European Values Study (eds. W.A. Arts, J.A.P. Hagenaars and L.C.J.M. Halman), Brill, Leiden, pp. 24–58.

- Goldstein, J. (1999) The leveling of divorce in the United States. Demography, 36 (3), 409–414.

- González, L. and Özcan, B. (2008) The risk of divorce and household savings behavior. Discussion paper no. 3726, IZA, Bonn.

- González, L. and Viitanen, T. (2009) The effect of divorce laws on divorce rates in Europe. European Economic Review, 53 (2), 127–138.

- Goode, W.J. (1962) Marital satisfaction and instability. A cross-cultural class analysis of divorce rates, in Class, Status, and Power. Social Stratification in Comparative Perspective (eds. R. Bendix and S.M. Lipset), The Free Press, New York, pp. 377–383.

- Goode, W.J. (1963) World Revolution and Family Patterns, Free Press, New York.

- Gruber, J. (2004) Is making divorce easier bad for children? The long-run implications of unilateral divorce. Journal of Labor Economics, 22 (4), 799–833.

- Hawkins, D.N. and Booth, A. (2005) Unhappily ever after: effects of long-term, low-quality marriages on well-being. Social Forces, 84 (1), 451–471.

- Heaton, T.B. (2002) Factors contributing to increasing marital stability in the United States. Journal of Family Issues, 23 (3), 392–409.

- Heuveline, P. and Timberlake, J.M. (2004) The role of cohabitation in family formation: the United States in comparative perspective. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66 (5), 1214–1230.

- Hewitt, B. (2009) Which spouse initiates marital separation when there are children involved? Journal of Marriage and the Family, 71 (2), 362–372.

- Härkönen, J. and Dronkers, J. (2006) Stability and change in the educational gradients of divorce: a comparison of 17 countries. European Sociological Review, 22 (5), 501–517.

- Jalovaara, M. (2012) Socioeconomic resources and first-union formation in Finland, cohorts born 1969–81. Population Studies, 66 (1), 69–85.

- Kalmijn, M. (2007) Explaining cross-national differences in marriage, divorce, and cohabitation in Europe. Population Studies, 61 (3), 243–263.

- Kalmijn, M. (2010) Country differences in the effects of divorce on well-being: the role of norms, support, and selectivity. European Sociological Review, 26 (4), 475–490.

- Kalmijn, M. (2011) Racial differences in the effects of parental divorce and separation on children: generalizing the evidence to a European case. Social Science Research, 39 (5), 845–856.

- Kalmijn, M. and Monden, C.W.S. (2006) Are the negative effects of divorce on well-being dependent on marital quality? Journal of Marriage and Family, 68 (5), 1197–1213.

- Kalmijn, M. and Poortman, A.-R. (2006) His or her divorce? The gendered nature of divorce and its determinants. European Sociological Review, 22 (2), 201–214.

- Kim, H.S. (2011) Consequences of parental divorce for child development. American Sociological Review, 76 (3), 487–511.

- Kitson, G.C. and Raschke, H.J. (1981) Divorce research: what we know; what we need to know. Journal of Divorce, 4 (3), 1–37.

- Landale, N.S. and Ogena, N.B. (1995) Migration and union dissolution among Puerto-Rican women. International Migration Review, 29 (3), 671–692.

- Lau, C.Q. (2012) The stability of same-sex cohabitation, different-sex cohabitation, and same-sex marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74 (5), 973–988.

- Lesthaeghe, R. (1995) The second demographic transition in Western countries: an interpretation, in Gender and Family Change in Industrialized Countries (eds. K.O. Mason and A.-M. Jensen), Clarendon Press, Oxford, pp. 17–62.

- Levinger, G. (1976) A social psychological perspective on marital dissolution. Journal of Social Issues, 32 (1), 21–47.

- Lyngstad, T.H. and Jalovaara, M. (2010) A review of the antecedents of union dissolution. Demographic Research, 23, 255–292.

- Martin, S.P. (2006) Trends in marital dissolution by women’s education in the United States. Demographic Research, 15, 537–560.

- Mastekaasa, A. (1994) Psychological well-being and marital dissolution. Journal of Family Issues, 15 (2), 208–228.

- McLanahan, S.S. and Sandefur, G. (1994) Growing Up with a Single Parent: What Hurts, What Helps? Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

- McManus, P.A. and DiPrete, T.A. (2001) Losers and winners: the financial consequences of separation for men. American Sociological Review, 66 (2), 246–268.

- Mignot, J.-F. (2009) Formation et dissolution des couples en France dans la seconde moitié du XXe siècle. Une évaluation empirique du pouvoir explicatif de la théorie du choix rationnel, Sciences Po, Paris.

- Morgan, S.P., Lye, D.N. and Condran, G.A. (1988) Sons, daughters and the risk of marital disruption. American Journal of Sociology, 94 (1), 110–129.

- National Center for Health Statistics (various years) Marriages and Divorces, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Washington, D.C.

- Ohlsson-Wijk, S. (2011) Sweden’s marriage revival: an analysis of the new-millennium switch from long-term decline to increasing popularity. Population Studies, 65 (2), 183–200.

- Oppenheimer, V.K. (1997) Women’s employment and the gain to marriage: the specialization and trading model. Annual Review of Sociology, 23, 431–453.

- Özcan, B. and Breen, R. (2012) Marital instability and female labor supply. Annual Review of Sociology, 38, 463–481.

- Pavalko, E.K. and Elder, G.H., Jr. (1990) World War II and divorce: a life-course perspective. American Journal of Sociology, 95 (5), 1213–1234.

- Pong, S.-L., Dronkers, J. and Hampden-Thompson, G. (2003) Family policies and children’s school achievement in single- versus two-parent families. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 65 (3), 681–699.

- Poortman, A.-R. and Lyngstad, T.H. (2007) Dissolution risks in first and higher order marital and cohabiting unions. Social Science Research, 36 (4), 1431–1446.

- Preston, S.H. and McDonald, J. (1979) The incidence of divorce within cohorts of American marriages contracted since the Civil War. Demography, 16 (1), 1–25.

- Pryor, J., Rodgers, B. (2001) Children in Changing Families: Life After Parental Separation, Blackwell, Oxford.

- Qureshi, K., Charsley, K. and Shaw, A. (2012) Marital instability among British Pakistanis: transnationalities, conjugalities, and Islam. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 35, 1–19.

- Raley, R.K. and Bumpass, L. (2003) The topography of the divorce plateau: levels and trends in union stability in the United States after 1980. Demographic Research, 8, 245–260.

- Ruggles, S. (1997) The rise of divorce and separation in the United States. Demography, 34 (4), 455–466.

- Sandström, G. (2012) Ready, Willing, and Able: The Divorce Transition in Sweden 1915–1974. Report No. 32 from the Demographic Database, Umeå University, Umeå.

- Sanz-de-Galdeano, A. and Vuri, D. (2007) Parental divorce and students’ performance: evidence from longitudinal data. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 69 (3), 321–338.

- Sayer, L.C. and Bianchi, S.M. (2000) Women’s economic independence and the probability of divorce: a review and re-examination. Journal of Family Issues, 21, 906–943.

- Sayer, L.C., England, P., Allison, P. and Kangas, N. (2011) She left, he left: how employment and satisfaction affect men’s and women’s decisions to leave marriages. American Journal of Sociology, 116 (6), 1982–2018.

- Schoen, R. and Canudas-Romo, V. (2006) Timing effects on divorce: 20th century experience in the United States. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68 (3), 749–758.

- South, S.J. and Lloyd, K.M. (1995) Spousal alternatives and marital dissolution. American Sociological Review, 60 (1), 21–35.

- Stanley, S.M., Rhoades, G.K. and Markman, H.J. (2006) Sliding versus deciding: inertia and the premarital cohabitation effect. Family Relations, 55 (4), 499–509.

- Stevenson, B. and Wolfers, J. (2006) Bargaining in the shadow of divorce: divorce laws and family distress. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121, 267–288.

- Stevenson, B. and Wolfers, J. (2007) Marriage and divorce: changes and their driving forces. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21 (2), 27–52.

- Sweeney, M. (2010) Remarriage and stepfamilies: strategic sites for family scholarship in the 21st century. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72 (3), 667–684.

- Teachman, J.D. (2008) Complex life course patterns and the risk of divorce in second marriages. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 70 (2), 294–305.

- Thomson, E. and Collella, U. (1992) Cohabitation and marital stability—quality or commitment. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 54 (2), 259–267.

- Thomson, E., Hanson, T.L. and McLanahan, S.S. (1994) Family structure and child well-being: economic resources vs. parental behaviors. Social Forces, 73 (1), 221–242.

- Thornton, A. and Rodgers, W.L. (1987) The influence of individual and historical time on marital dissolution. Demography, 24 (1), 1–22.

- Thornton, A. and Young-De Marco, L. (2001) Four decades of trends in attitudes toward family issues in the United States: the 1960s through the 1990s. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 63 (4), 1009–1037.

- Twenge, J.M., Campbell, W.K. and Foster, C.A. (2004) Parenthood and marital satisfaction: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 65 (3), 574–583.

- Umberson, D., Williams, K., Powers, D.A. et al. (2005) As good as it gets? A life course perspective on marital quality. Social Forces, 84, 493–511.

- United Nations (various years) Demographic Yearbook, United Nations, New York.

- Uunk, W. (2004) The economic consequences of divorce for women in the European Union: the impact of welfare state arrangements. European Journal of Population, 20 (3), 251–285.

- Wagner, M. and Weiß, B. (2006) On the variation in divorce risks in Europe: findings from a meta-analysis of European longitudinal studies. European Sociological Review, 22 (5), 483–500.

- Wang, H. and Amato, P.R. (2004) Predictors of divorce adjustment: stressors, resources, and definitions. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62 (3), 655–668.

- Wolfers, J. (2006) Did unilateral divorce raise divorce rates? A reconciliation and new results. American Economic Review, 96 (5), 1802–1820.

- Wolfinger, N.H. (2005) Understanding the Divorce Cycle: The Children of Divorce in Their Own Marriages, Harvard University Press, Cambridge.