John Ledyard, “a new character to the world” and the first citizen of an independent United States to explore the Middle East.

America’s second international treaty, signed by Thomas Jefferson and John Adams and bearing the imperial seal of Morocco with the Islamic date of “Ramadan, 1200.”

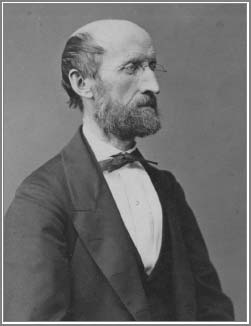

Professor George Bush, Hebrew scholar and author of Valley of Vision (1844), which advocated renewed Jewish statehood in Palestine, and an ancestor of two later U.S. presidents of the same name.

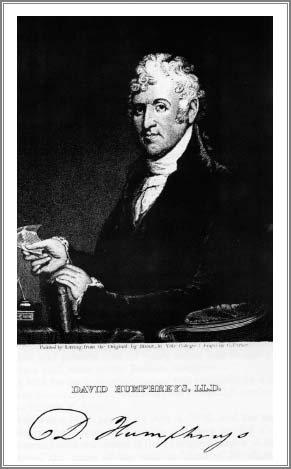

“The rovers who infest thy waves have seiz’d our ships and made our freemen slaves”—the poet-diplomat David Humphreys, who negotiated the release of American hostages in the Middle East in 1795.

Joel Barlow, America’s special emissary to the Barbary pirates. The dey of Algiers warned him, “I will put you in chains and declare war.”

George Sandys, treasurer of the Virginia colony and veteran mercenary in the Middle East. “I think there is not an object that promiseth so much,” he wrote of the region, “[yet] so deceiveth.”

The explorer of Persia in 1806 who speculated that Middle Eastern oil might someday be used as fuel—and discoverer of the flower that bears his name—Joel Roberts Poinsett.

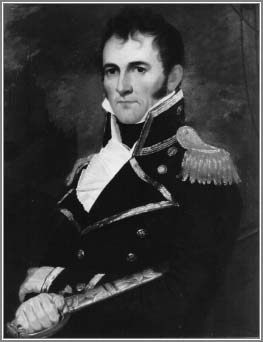

William Bainbridge, the ill-starred captain who was forced to transport Algerian tribute and who lost his warship to Tripoli’s pirates.

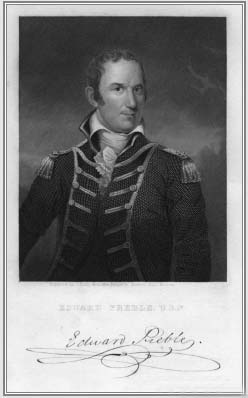

“The Moors are a trecherous set of villains”—Commodore Edward Preble, commander of America’s Mediterranean Squadron, 1803.

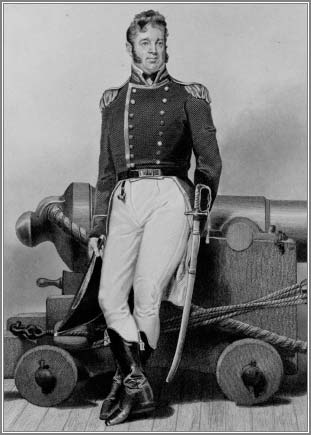

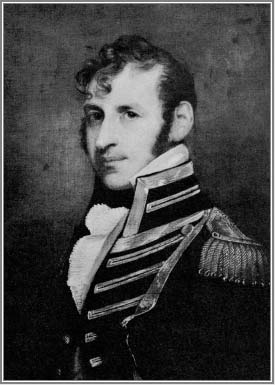

“My country right or wrong”—Stephen Decatur, the Navy’s youngest captain and hero of America’s 1815 victory in the Middle East.

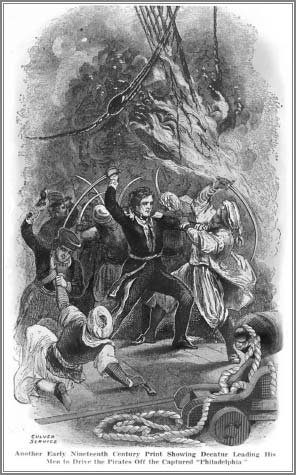

Decatur in battle, 1805, driving pirates off the captured Philadelphia.

An early champion of Zionism, and the first of many American Jewish emissaries to the Middle East, Mordecai Manuel Noah.

David “Sindbad” Porter, painted after the Barbary Wars and before his appointment as America’s first ambassador to the Ottomans. “Salaams are an infernal nuisance,” he snapped after meeting the sultan. “Why the devil can’t the man be satisfied with a decent salute?”

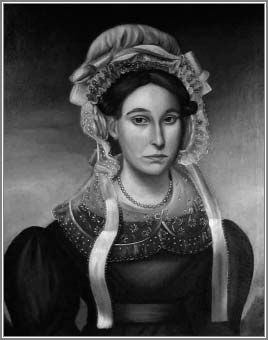

The Washington socialite and revivalist preacher Harriet Livermore, who attempted to establish an American colony in Palestine in 1837. John Quincy Adams called her “the most eloquent speaker [he had] ever listened to.”

Cyrus Hamlin, the industrial-minded missionary from Maine who moved to the Middle East in 1842 and founded the region’s first modern university.

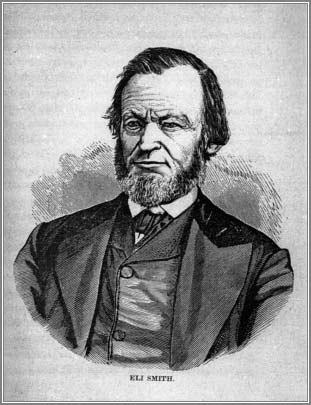

Eli Smith, linguist and inventor of “American Arabic” type, who recommended frequent visits by U.S. warships to the Middle East. “They ought to know that we are a power,” he said.

Warder Cresson, the quirky Jerusalem consul who, in the 1850s, traded “the sawdust of Christianity” for the “good old cheese itself” and converted to Judaism.

James Turner Barclay, physician, scientist, architect, and missionary to Palestine in 1850. “We will go with you,” he pledged to the Jews, “for we have heard that the Lord is with you.”

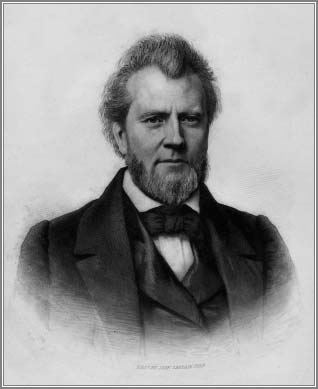

George Perkins Marsh, father of American conservationism and founder of the U.S. Army Camel Corps, created in 1857 to strike “a salutary terror” into “the Comanches and other Rocky Mt. Bedouins.”

Memorial in Quartzite, Arizona, to the U.S. Camel Corps and its famed Arab guide, Hi Jolly (Haji Ali).

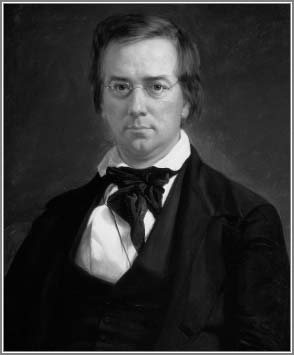

“Earnest Christian and lover of the adventure,” U.S. Navy Captain William Francis Lynch, who in 1847 became the first Westerner to navigate the Jordan River from the Sea of Galilee to the Dead Sea.

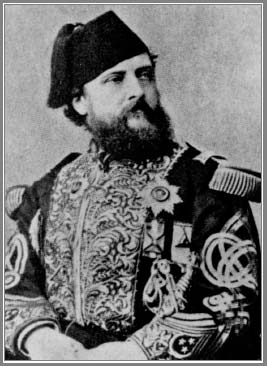

Ismail Pasha, the Egyptian khedive who hired Civil War veterans to modernize his army. “When this shall be accomplished,” he told them, “as it will be Inshallah, I will bestow upon you the highest honors.”

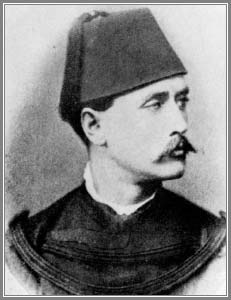

Thaddeus Mott, mercenary, gold miner, and American recruiter for a Middle Eastern army.

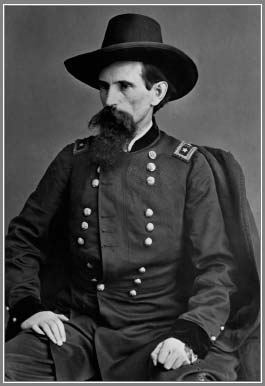

Veteran of seventy-five battles and inspector general of the Egyptian army from 1869 to 1875, William Wing “Old Blizzards” Loring.

Charles Pomeroy Stone, the “American Dreyfus” and Civil War “soldier of misfortune” who served as Egypt’s chief of staff and as senior engineer in constructing the Statue of Liberty.

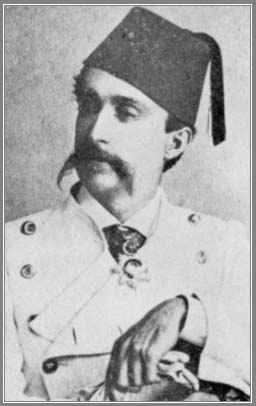

The swashbuckling James Morris Morgan, Jefferson Davis’s former bodyguard and soldier of Egypt, circa 1870.

Charles Chaillé-Long, the effete but effective explorer of the Nile in 1874. “The entire Nile basin passed under the protectorate of Egypt,” he proclaimed, “and the chief object of my mission was accomplished.”

Soldier and explorer of the Sudan, Erastus Sparrow Purdy.

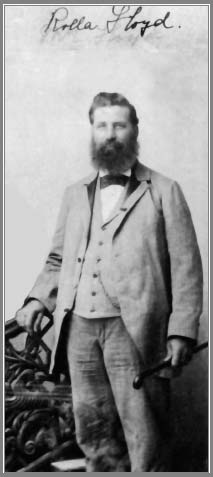

A native of Indian River, Maine, who joined the George Adams colony and moved to Jaffa in 1866, Rolla Floyd became the first American tour guide in Palestine, accompanying—among other dignitaries—Ulysses S. Grant.

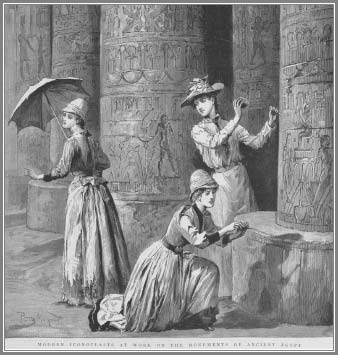

American tourists chipping souvenirs from an ancient Egypt temple, “saving precious fragments from the ruin to which they are doomed.”

“America is the Palestine of political salvation,” wrote Secretary of State and American Middle East traveler William Henry Seward.

“A glorious gleaming pageant.” Ulysses and Julia Grant visit Egypt in 1878.

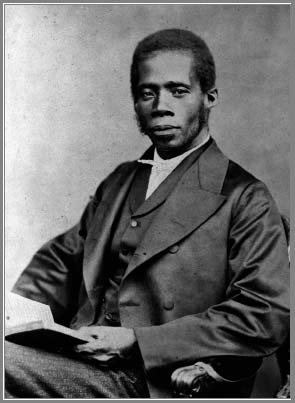

An African-American preacher of peace in the Middle East, Edward Wilmot Blyden.

Lew Wallace, Civil War hero, hunter of Jesse James, and author of Ben-Hur, America’s ambassador to the Ottomans in 1881.

An advertisement for the memoirs of Mark Twain’s Middle Eastern travels, which sold over half a million copies—“right along with the Bible,” he quipped.

An American consul in Alexandria, Elbert Eli Farman, procurer of Cleopatra’s Needle and staunch opponent of the British conquest of Egypt.

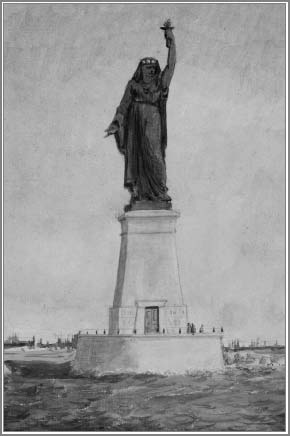

“Egypt Bringing Light to Asia,” the original Lady Liberty intended by its creator, Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, to grace the entrance to the Suez Canal.

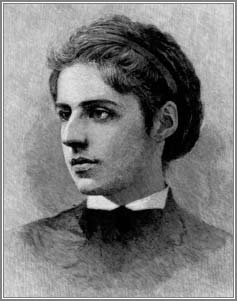

“Wake, Israel, wake!”—Emma Lazarus, poet and proponent of American Zionism.

The American missionary to Arabia in 1890 and father of Saudi-American relations, Samuel Marinus Zwemer.

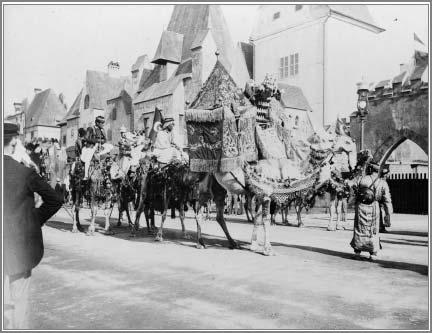

“We were all knocked silly!” Middle East exhibits at Chicago’s 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition.

Angel of the Battlefield and founder of the American Red Cross, Clara Barton, who worked to save Turkey’s Armenians in 1896.

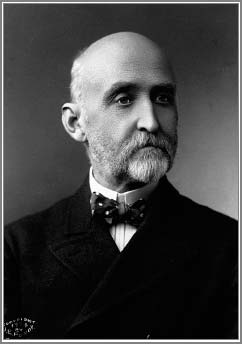

Alfred Thayer Mahan, eminent naval historian and coiner of the term “Middle East.”

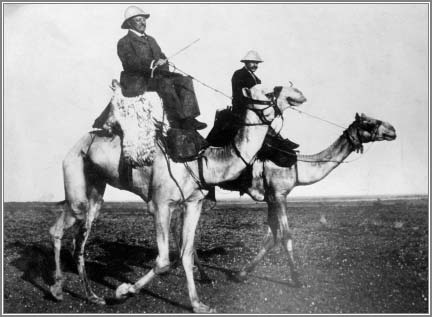

Theodore Roosevelt, whose critique of “the mass of…bigoted moslems” earned him the ire of many Middle Easterners, visits Egypt in 1910.

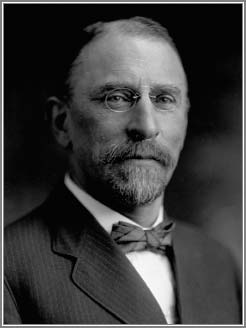

“Our people will never forget these massacres”—Henry Morgenthau, American ambassador to the Porte during the Armenian genocide, 1914–15.

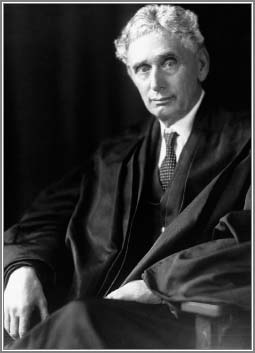

Louis Dembitz Brandeis, the first Jewish Supreme Court justice, wrote, “There is no inconsistency between loyalty to America and loyalty to Jewry.”

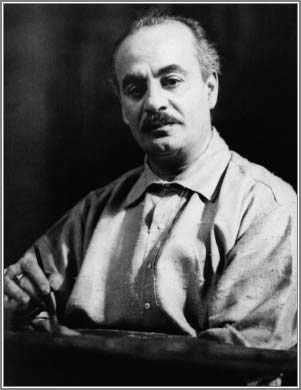

Gibran Khalil Gibran, poet, author of The Prophet, and proponent of Arab nationalism.

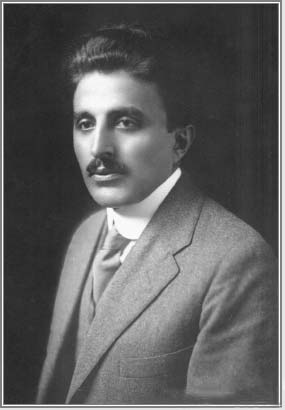

Ameen Rihani, the voice of Arabism in America, who was determined to “bring to the West some Eastern repose.”

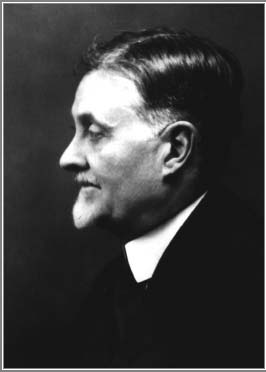

American champion of Arabism, and arch anti-Zionist, Charles Crane.

Present at the creation. Wilson (right) and Balfour at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference and the birth of the modern Middle East.

The making of a Middle East myth, T. E. Lawrence (left) and Lowell Thomas.

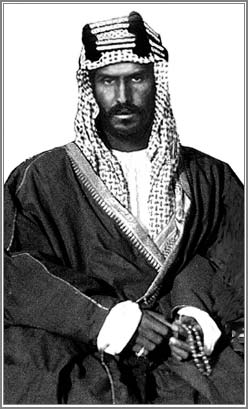

“Every line of him…told of intelligence, energy, determination, and nerves of compelling power”—‘Abd al-’Aziz ibn Saud, the founder of Saudi Arabia and of the kingdom’s complex alliance with the United States.

Golda Meir, the vice president of her junior class, in the Milwaukee State Normal School yearbook, The Echo, in 1917—“I was not fleeing from oppression [in America]…. I was leaving to participate in the setting up of independence for my own people.”

“Arab-Jewish relationships should have been the central point of our Zionist thinking”—the Hadassah founder, Henrietta Szold.

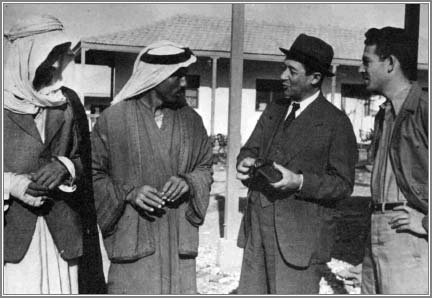

Judah Leib Magnes (hatted, in center), American Zionist leader and advocate of a binational Arab-Jewish state in Palestine.

The Zionist leader David Ben-Gurion in a Jewish Legion uniform shortly after his sojourn in New York. “The weight of our enterprise is in America.”

The dapper State Department veteran Loy Henderson, avid Cold Warrior and opponent of the Jewish state.

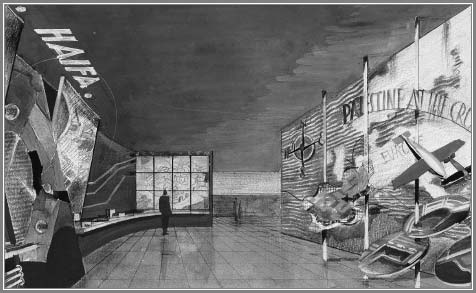

The Palestine Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair, 1939. Visitors were feted with “delicious Palestinian dishes,” such as schnitzel, and greeted by “the most beautiful girl in Palestine,” a member of the Haganah.

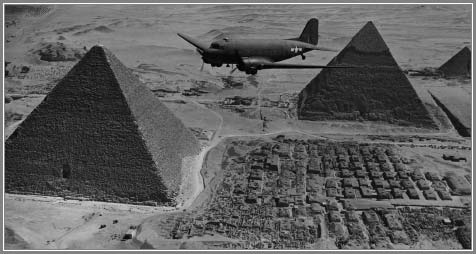

“A strange noise travels toward the pyramids”—American forces on duty in Egypt during World War II.

King ibn Saud and Franklin Delano Roosevelt aboard the USS Quincy, February 1945. “I learned more about the [Middle East] by talking with Ibn Saud for five minutes than I could have learned in the exchange of three dozen letters.”

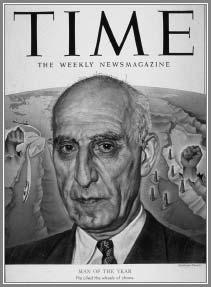

Liberty-loving Middle Nationalist or anti-American ally of communism? Mohammad Mossadegh of Iran.

Golda Meir and Henry Kissinger during shuttle diplomacy of 1974. “Oh, Mr. Secretary,” she exclaimed, “I didn’t know you kissed girls, too!”

The Camp David Accords: Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, President Jimmy Carter, and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin (from left to right). The treaty, claimed Carter, “had now become almost like the Bible.”

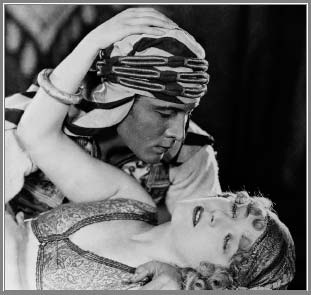

Middle Eastern fantasy seduces early Hollywood: Rudolph Valentino as the libertine, liberty-loving nomad and Vilma Banky as the Western naïf in the 1926 sensation The Son of the Sheik.

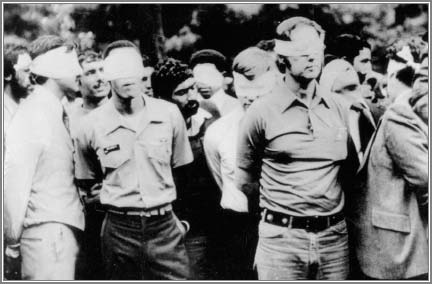

November 1979: American hostages in Teheran during their 444-day incarceration. “We will teach the CIA not to interfere with our country,” the Iranians chanted. “We will teach you about God.”

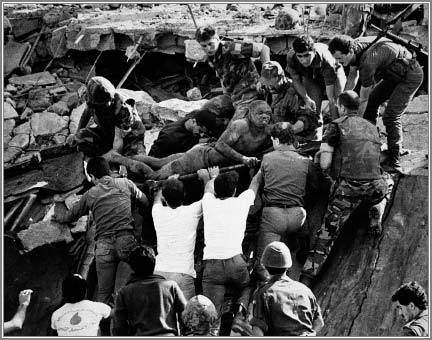

The bombing of the Marine headquarters in Beirut, December 1983, which claimed 241 American lives and introduced the United States to large-scale terror.

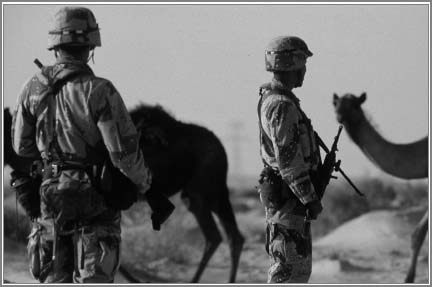

GIs in Kuwait. The Gulf War, 1991.

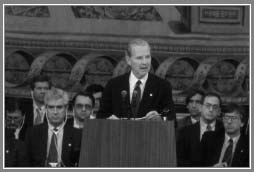

In search of the new world order, George H. W. Bush’s Secretary of State James Baker at the Madrid peace conference in 1991.

“Shalom, salaam, peace. Go as peacemakers.” From left to right, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, President Bill Clinton, and PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat sign the Declaration of Principles, September 1993.

The attack on the USS Cole, October 2000. “We are at war,” the CIA concluded, but the administration remained passive.

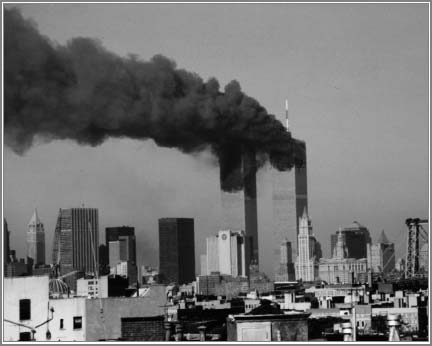

9/11: the day the fantasy died (photograph taken by the author’s son, from Brooklyn Heights).

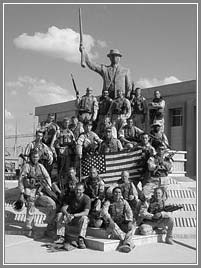

U.S. Marine Second Platoon Bravo Company, First Recon Battalion, photographed in Iraq during the Second Gulf War. First Lieutenant Nathaniel Fick stands second row from the bottom.