Chapter 3 – The New Kingdom, 1400 – 1200 BCE

The New Kingdom was the height of Hittite power throughout Anatolia. The New Kingdom is also called the Hittite Empire period and only lasted for two short centuries before the Hittites became scattered and decentralized once more. One of the most significant developments of this time was the change in how people viewed the function and place of the king. While before the monarch was seen as the first among equals, royalty began to develop a divine aura. Nobles and commoners would now call the king “My Sun,” and he and the queen were associated with deities. Following previous developments from the Middle Kingdom when succession to the throne became hereditary, people began to associate the royal family with divinity. In essence, a version of the divine right to rule was born.

In addition, the kings took on a new role in religion. Before, the monarchy did not have a strong religious element. Now, each king was considered a high priest of the gods, responsible for currying their favor and carrying out their word. Many of them would go on grand tours of the kingdom, which included visits to holy sites, participating in festivals, making sure sanctuaries were kept in good condition, and being present at important sacrifices or rituals.

Tudhaliya I

The New Kingdom began with the coronation of King Tudhaliya I—potentially not the first of his name since the records are unclear—in c.1430 BCE. Not much is known about his reign except that he conquered an area known as Assuwa. Assuwa was a league of 22 separate Anatolian states formed sometime before its defeat by the Hittites around 1400 BCE. Not much is known about Assuwa except that its fall would become the shining moment of Tudhaliya I and the nascent Hittite Empire. Assuwa would have been located around the northwest of Anatolia, especially since some of its states are believed to appear in ancient Greek literature.

Following his success against Assuwa, Tudhaliya I attacked its successor state, an area called Arzawa. Arzawa was primarily Luwian, a separate group of people in Anatolia who spoke and wrote their own language without relying on another culture’s characters. After the initial attack by Tudhaliya I, Arzawa joined an anti-Hittite league and eventually faced its end under the powerful New Kingdom. Afterward, Tudhaliya I additionally attacked and conquered the Hurrian states of Aleppo and Mitanni.

Suppiluliuma I

Success did not follow Tudhaliya I. Despite his ability to expand the Hittite Empire, it immediately entered another weak period. It was so bad that the state’s enemies were able to attack from all sides and eventually razed Hattusa. The empire lost a good portion of its territory under the rulers which immediately followed Tudhaliya I – including his own son – and did not see another strong ruler until the rise of Suppiluliuma I.

Suppiluliuma I was crowned around 1344 BCE and ruled until roughly 1322 BCE. His parents were Tudhaliya II and Daduhepa. He worked under his father as a general and achieved his first major military success against the Azzi-Hayasa, a confederation of small kingdoms near the Hittites, and the Kaskas. When the two defeated peoples attempted to rally around charismatic leaders, Suppiluliuma worked with his father to crush them once more.

He could also be considered one of the major defeaters of Egypt, capable of regaining valuable territory in the region of Syria. Suppiluliuma I recognized that the poor rule and diplomacy of Pharaoh Akhenaten gave the Hittites unprecedented opportunities to reclaim land. His tactics would eventually lead to the Hittites gaining some of Egypt’s vassal states right out from under them.

Pharaoh Akhenaten and His Family

Suppiluliuma took advantage of the pharaoh’s growing difficulties with the king of Mitanni, Tushratta. Akhenaten's father originally made a deal with Mitanni against the Hittites to try to gain control of its region in Anatolia. As part of the agreement, Egypt was supposed to send several statues of solid gold as a portion of a bride price paid to Tushratta since his daughter married Ahkenaten’s father and eventually the new pharaoh himself. Tushratta accused him of sending gold-plated statues rather than full ones. He even sent a letter to Ahkenaten complaining about the situation, stating:

“But my brother [i.e., Akhenaten] has not sent the solid [gold] statues that your father was going to send. You have sent plated ones of wood. Nor have you sent me the goods that your father was going to send me, but you have reduced [them] greatly. Yet there is nothing I know of in which I have failed my brother. Any day that I hear the greetings of my brother, that day I make a festive occasion... May my brother send me much gold. [At] the kim[ru fe]ast...[...with] many goods [may my] brother honor me. In my brother's country gold is as plentiful as dust. May my brother cause me no distress. May he send me much gold in order that my brother [with the gold and m]any [good]s may honor me.”

[iii]

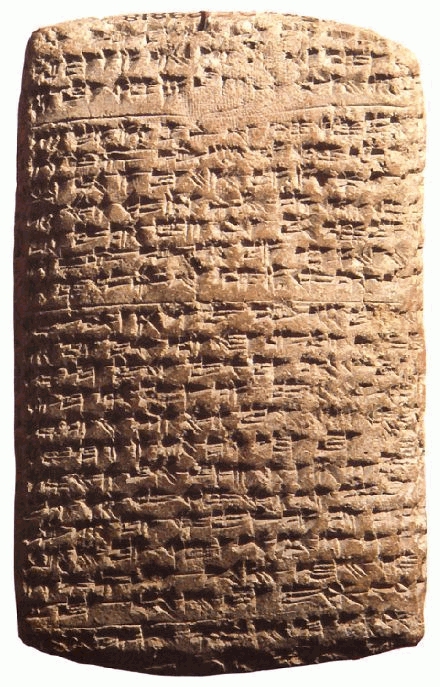

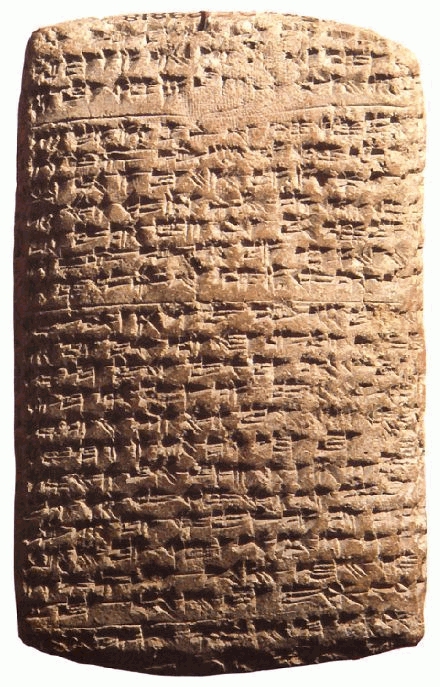

The brother he refers to is Akhenaten, who is failing to fulfill the agreement. Tushratta further notes that his original messengers saw the gold, lapis lazuli, and the cast statues that were to be sent. Tushratta believes these originals were not delivered and that Akhenaten replaced them with cheap alternatives. This document, and complaints from other vassals and allied states, can be found in the Armana Letters, a group of significant correspondences between Akhenaten and others. Vassal states are subordinate states which typically provide military service and tribute to a dominant kingdom, culture, or other political body. In the Armana Letters, it becomes clear that the pharaoh was disappointing many of Egypt’s allies by failing to supply adequate resources and money to people who were supposed to be in league with the powerful kingdom. One of these letters appeared in an earlier chapter as an example of cuneiform and contains information from the leader of the Amurru, a small kingdom in the vicinity of modern Syria.

One of the Armana Letters

The Armana Letters reveal other flaws in Akhenaten’s diplomacy of which Suppiluliuma I could take advantage. In particular was the pharaoh’s unwillingness to assist a group of allies who rebelled against the Hittites and were captured by soldiers. They wrote to the pharaoh and begged for troops to help them, but Akhenaten did not answer most of their letters and ignored the pleas. He did dispatch troops to solve a problem in Canaan, but otherwise seemed content to allow the vassals to suffer. He especially would not intervene in what he viewed as petty political disputes, which led to great problems in the region of Amurru.

Rib-Hadda of Byblos faced constant trouble as the ruler of one of the border states for the Egyptian Empire. He was ousted from power and received no help from Akhenaten. He eventually turned to a man named Aziru for assistance, only to be sent to a separate kingdom and no doubt executed. His enemy, Aziru, was held for a year by the pharaoh under accusations of deliberately plotting the end of Rib-Hadda, but Akhenaten released him. Upon returning to his kingdom, Aziru defected to the Hittites, adding to the growing power of the New Kingdom under Suppiluliuma I. The entire border province of Amurru in Syria came under Hittite control, giving them a strong foothold in the region and allowing the Hittites to regain some of their old strength.

Suppiluliuma I was additionally able to reconquer Aleppo, which had been lost, and defeat several other city-states. He retook Mitanni so that it was reduced to a position of vassalage and handed several other territories over to his vassals to create a stable place in Asia Minor. Eventually, he possessed more control than the once-powerful Egypt, and Egypt attempted to form a marriage alliance although it was never consummated following the Hittite prince’s murder. No one is quite sure who killed the prince, since his traveling party discovered him dead one morning of unnatural causes. The Hittites blamed the Egyptians, who denied any knowledge of the incident and claimed they would have no benefit from the prince’s death. Either way, the two parties were unable to overcome their bitterness of the incident and another prince was not sent to complete the arrangement.

However, all of this prestige could not last. The Middle Assyrian Empire was also hitting its heights of power under the rule of Ashur-uballit I. Assyria took the lands of the Hurrians and Mitanni, despite Suppiluliuma I’s best attempts to use his own military strength to preserve his position. The Assyrians began to take lands from the Hittites in Asia Minor, as well as several city-states previously won from Egypt. Suppiluliuma I and his wife eventually perished from the spread of a plague carried by the peoples of the territories taken from Egypt.

Mursili II

The next influential ruler would be Mursili II, who took over from his brother, the eldest son of Suppiluliuma I. His brother also died of the plague, and Mursili II faced frequent rebellions during the first years of his reign because of his relative youth and inexperience. While not a minor, he did take control as a teenager and was viewed as incapable of leadership. The Kaskas and Arzawa in particular fought against the Hittites, but both regions were spectacularly vanquished.

Mursili II wrote about some of his difficulties and triumphs in documents known as the Annals, which managed to survive the sands of time. Notably, he mentioned the continuing scorn of his foes and how his status made many of them rebel in a document where he recorded some of their more common quotes:

“You are a child; you know nothing and instill no fear in me. Your land is now in ruins, and your infantry and chariotry are few. Against your infantry, I have many infantry; against your chariotry I have many chariotry. Your father had many infantry and chariotry. But you who are a child, how can you match him?”

[iv]

The Hittite Empire During the Reign of Mursili II

Experts believe Mursili II died of natural causes after leading the Hittites for 25-27 years. The map above demonstrates the extent to which he managed to expand and secure the borders of the growing Hittite Empire. He also attacked several areas to the west, including Millawanda, an area believed to be under the control of the Mycenaean Greeks

The Hittite Empire continued to hold an enviable position in Asia Minor and the Far East. The New Kingdom had access to massive quantities of resources, prosperous trade routes, and vassal states willing to pay tribute in exchange for military protection and a modicum of power. The Hittites had even managed to rebound after struggling with the Assyrians and knocked Egypt back out of Anatolia. But this position could not last. Following a lasting pattern of the Hittites, weak rulers would replace the strong, and there wouldn’t always be enough military might and prowess to go around. The Hittites would find their next great opponent from an old enemy: the Egyptians. Eventually, ongoing struggles and the inability to protect all of its territory would sound the end of the great Hittite Empire once and for all.