Chapter 5 – The Syro-Hittite or Neo-Hittite Kingdoms

The term “Neo-Hittite” refers to the concept that the states which followed the fall of the New Kingdom were the “new Hittites.” After the Bronze Age collapse and the start of the Iron Age, centralized government for the Hittites no longer existed. Instead, the Hittite culture adapted to a new environment and the people formed what would be known as the Syro-Hittite or Neo-Hittite kingdoms. These kingdoms were less regulated cities scattered through the region which borrowed from the Hittite way of life as well as from the cultures of nearby neighbors. Over time, these kingdoms would become vassals of the Assyrians and take on new cultural practices which rendered some of the old Hittite components obsolete.

The Differences Between the Old Hittite and Neo-Hittite Kingdoms

With so many groups moving into Anatolia during the end of the Bronze Age, the composition of the Neo-Hittite kingdoms vastly differed from that of their predecessors. Historian Trevor Bryce summed up the characteristics of a Neo-Hittite kingdom efficiently by pointing out four main factors.

[vi]

-

Most of them were in the same geographic region of “Hatti” throughout Anatolia and Syria as the original Hittite kingdom.

-

Documents discovered in the cities were written in the Luwian hieroglyphic script and language, which had come to replace the traditional cuneiform and tongue of the Hittites during the later years of control.

-

Rulers of the states had traditional Hittite monarch names translated into Luwian.

-

Iconography and architectural designs from the old Hittite kingdom can be seen in the new states, indicating a cultural connection between the two.

The Luwians were a group of people with a shared language who populated several areas within Asia Minor. Over time, they gradually assimilated or began to share their culture with other groups throughout the region, including the Hittites. Historians can tell they usually lived alongside other peoples and would join pre-existing states, but never formed their own unified civilization. They possessed a unique hieroglyphic script which would be adopted by the largest group they lived and traded with, the Hittites. The switch from cuneiform to Luwian hieroglyphs in the Hittite kingdom was a slow process but seemed to be gaining speed towards the end of the Bronze Age as the Hittites assimilated into the surrounding cultures. While this might seem like a development, it actually meant that the Hittites were no longer the driving cultural force in the region since they begin to adopt aspects of different cultures whereas during the New Kingdom, they were the main influencers in Anatolia.

Anatolian Seal of Tarkummuwa

This seal is one of the best examples of what the Hittite language looked like when written in the hieroglyphs that became popular during the time of the Neo-Hittite cities. It shows the Hittite ruler Tarkummuwa with a bilingual description of him in the native Hittite language as well as translated into hieroglyphs, before the Hittite language began to fade away. It is one of the most influential artifacts for researchers to be able to figure out what the Hittite tongue might appear as in the new hieroglyphs.

Iconography and Architecture

Archaeologists are able to tell which cities belonged to the Neo-Hittites based on their unique iconography and architecture. On the one hand, the cities had no defining shape, unlike the towns from other cultures. They could be circular, rectangular, or irregular depending on location and environment. Each city did have a fortified citadel to hold the palaces, forcing a separation of the commoners and elites.

Other architectural clues included palace and temple designs with ancient Syrian influence, dating back to the second or third millennia BCE. Ramparts, gates, palaces, and reliefs were decorated with stone blocks or orthostats, which were rectangular slabs set upright, similar to the pillars which hold up Stonehenge. These elements were crucial to older forms of Hittite iconography and architecture and provide important clues for understanding how Hittite culture and life changed with the arrival of the Aramaeans and their continued contact with them.

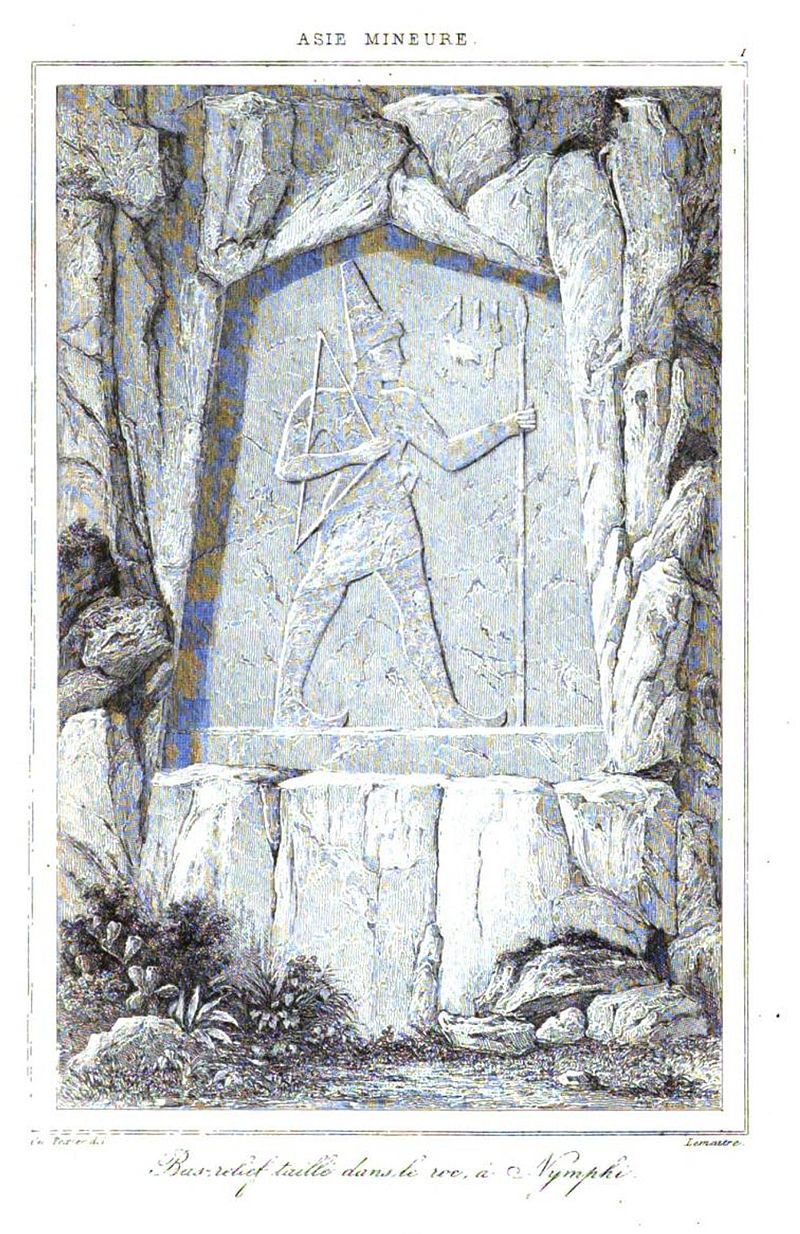

Illustration of the Hittite Stone Relief of King Tarkasnawa

The Aramaean and Luwian Influence Continued

The Aramaeans were a northwest Semitic Aramaic-speaking group of tribes which formed a confederation that lived in Syria—known as Aram, hence the name—from roughly the eleventh to eighth centuries BCE. As a whole, they would become the Hittites most prominent opponent for control in Syria following the fall of the Hittite kingdom because their population was spreading and their culture was thriving. It is from the Aramaeans that the term “Syro-Hittite” originates, as over time the Hittites would embrace more and more aspects of Aramaean culture in their small cities throughout the region.

The Aramaeans possessed several major states, including Bit-Agusi, Sam’al, and the kingdom of Damascus. Many of these significant urban centers were based around the locations of former Hittite cities. A popular theory of historians, archaeologists, and anthropologists is that the Hittites, having been displaced by the collapse of their kingdom, migrated to these new urban areas. Along with them came a mass migration of the Luwians into Anatolia, explaining why their language and alphabet became dominant while Hittite terms were still used.

Several scholars attempted to distinguish between the culture of the previous Hittite kingdoms and those influenced by the Luwians, but did not notice any differences besides architectural and literary clues. Acculturation was still the name of the game during the Syro-Hittite kingdoms and many of the same deities were still worshipped. Since all of the regional religions had already been adopted as a whole or in part by the Hittites to form their own, there wasn’t much left for the Luwians to bring to the table when confronted with the Hittite religion. While the writing script did change, it’s implied that much of the local culture and societal structure of the Hittites remained the same, especially in regions which had been rural or nomadic to begin with.

The Neo-Assyrian Empire

Eventually, the Syro-Hittite kingdoms assimilated into the Neo-Assyrian Empire, which replaced the Old Assyrian Empire. The Neo-Assyrian Empire lasted from 911 – 612 BCE and encompassed much of Asia Minor and the Far East. The map below demonstrates the Assyrians managed to conquer the majority of the regions previously held by the Hittites during their glory days.

Map of the Neo-Assyrian Empire

The Hittites came under Assyrian control during the reigns of two figures, Adad-nirari II and Ashurnasirpal II from 911 – 859 BCE. Adad-nirari II launched numerous military campaigns designed to carve territory out of preexisting empires, including the 25th

Dynasty of Egypt, also called the Nubian Dynasty. Adad-nirari II was able to lay claim to numerous smaller states as well, including many of the Neo-Hittite kingdoms. Among his conquests were Israel, Judah, most of the land surrounding the major Neo-Hittite cities, Persia, Canaan, and Cyprus. He additionally exacted tribute from others, making them vassal states.

Surprisingly, Adad-nirari II was one of the first leaders in Anatolia and the nearby regions to start deporting people of different ethnic or cultural backgrounds to the borderlands. Among those targeted by his policies were the Aramaean and Hurrian populations, but not the Hittites. It was his, and many of the future Assyrian kings’, policy to campaign annually during a consistent portion of the year, which helped the empire maintain control while also fueling expansion but also meant that the Hittites faced a constant onslaught from the Assyrian nobility, who wanted to evict them from their conquered homes.

Adad-nirari II was not satisfied with only the Neo-Hittite cities and the current Egyptian dynasty. He also went to war twice with the powerful leader of Babylonia and managed to annex huge swaths of land around the Diyala River. His direct successor then consolidated all of these holdings and continued to push into Asia Minor. He did not last long and would be replaced with an equally strong leader, Ashurnasirpal II.

The Powerful Ashurnasirpal II

Ashurnasirpal II further embarked on a massive program of expansion which took even more land away from neighboring states. He invaded the nearby area of Aram and conquered the Aramaeans and Neo-Hittites which lived there, eliminating one of the last Neo-Hittite outposts in the process. He moved his capital to the city of Kalhu and started to boast about the military prowess of the Assyrians while building extensive cultural centers throughout the empire. The Neo-Hittites would live in many of these, not as receivers of the culture, but often as slaves.

Ashurnasirpal II was infamous for his brutality and was a strict and a shrewd administrator. He realized it was foolish to rely on local leaders to become governors in conquered territories, so he would send his own officials. He also enslaved many of the peoples whom he conquered, taking them into captivity and forcing them to labor on his cultural projects. Several stone reliefs show this brutality, which would have affected the Neo-Hittites since they lived in many of the taken regions. As an odd fact, while male slaves or enemy warriors were frequently depicted as being tortured, naked, or mutilated, female slaves were usually seen in full-length gowns without the accompanying violence. If any part of the body was shown in detail, it would only be one. For example, one picture might have a woman fully clothed with her feet exposed, while another might show her breast.

A Relief of the Successful Ashurnasirpal II after Battle

Ashurnasirpal II additionally continued policies which called for the mass deportation of conquered peoples to the borderlands of the empire, which were still under Assyrian control but had fewer resources. This policy would be continued under his successor, Shalmaneser III. Shalmaneser III was responsible for eliminating the Hittites of Carchemish, a final holdout in Syria not associated with the original Hittite kingdoms. Those who survived paid tribute and were eventually incorporated into the Neo-Assyrian Empire as well.

Incorporation into the Assyrian society not only happened in Carchemish, but in the very center of the once proud Hittite civilization. Hattusa continued to be a major city under Assyrian control and many Neo-Hittite citizens lived in the empire, but this is where the story of the Hittites as their own people gradually came to an end. They no longer held on to their own culture and society but were instead assimilated into the powerhouse that was the Neo-Assyrian Empire. By the time of the empire’s fall in the late fifth century BCE, the Hittites as their own group no longer seemed to exist.