CHAPTER 19

THE AIR WAS THICK WITH DUST AND MAGIC.

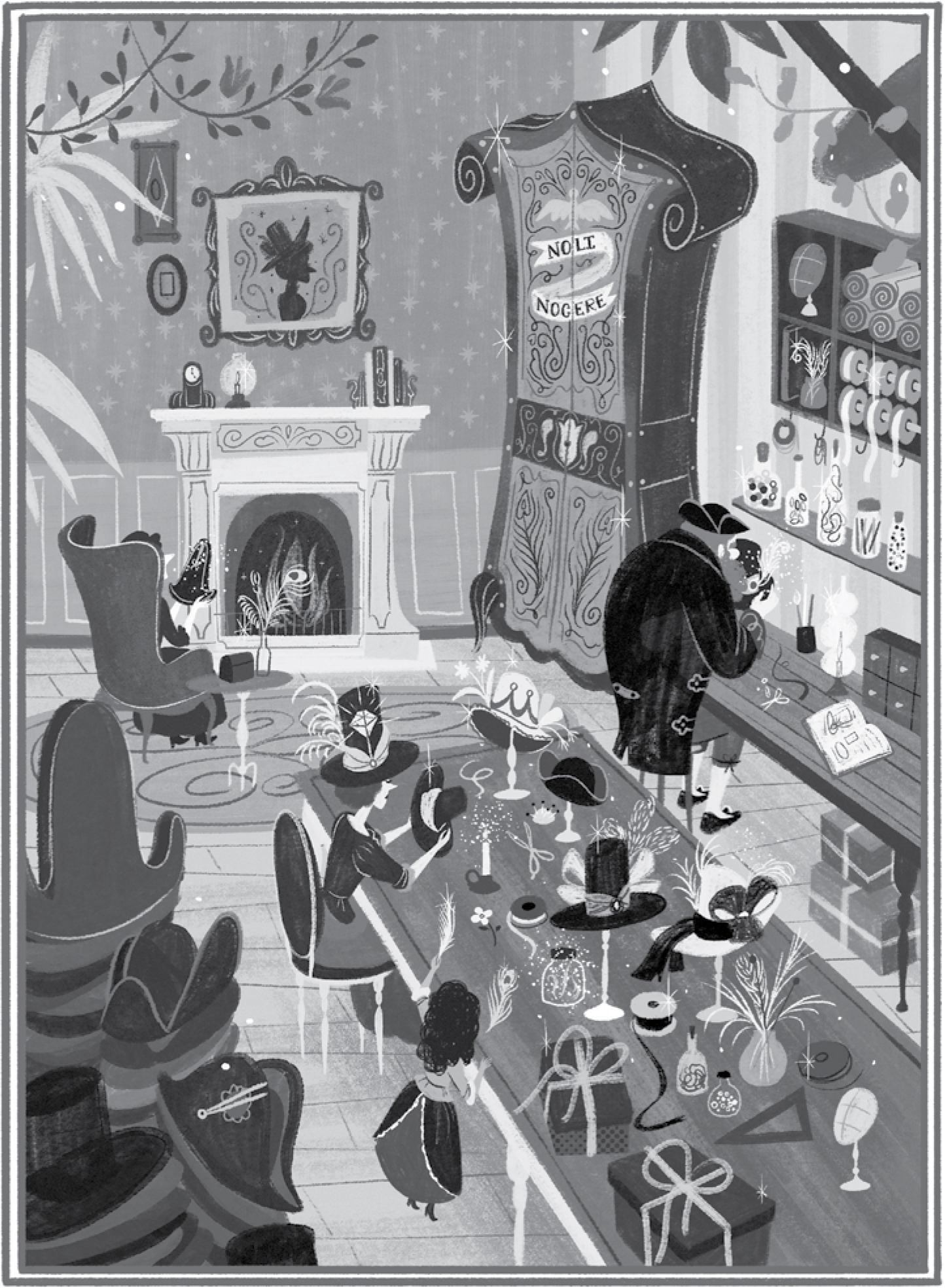

Before her eyes adjusted to the gloom, Cordelia could smell the history in the building around her: there was the chalky scent of marble floors and the resin sweetness of wood-paneled walls. She felt her way forward and brushed through velvet curtains, prickly with age.

She was in a colossal circular chamber. Jewel-colored light spilled through a vast stained-glass window, scattering a dazzling pattern on the wide wooden floor. Soaring pillars circled the room and a domed ceiling rose high above her, garlanded with plaster flowers. Tapestries and paintings adorned the walls, carved wooden crests hung above the doors, and a sweeping mahogany staircase curled in an elegant arc to a gallery above.

Cordelia walked into the middle of the enormous room, leaving a track of footprints in the dust. Around her, the air hummed with unspoken magic. She felt like she was standing inside a secret.

“I am sorry we’ve never told you about the Guildhall, Cordelia,” Aunt Ariadne murmured, “but we did not really know how to begin. … Besides, a meeting of Makers has not been called for thirty years.”

“It was built more than two hundred and fifty years ago, by King Henry VIII.” Uncle Tiberius beckoned her over to look at a large oil painting on the wall. “There he is. Notoriously vain, was King Henry. He appointed families to be Makers of the Royal Garb and every few weeks he’d come riding up and want to try on new outfits. This is where our ancestors worked, Making hats for the king.”

Cordelia peered up at the painting. It depicted the familiar broad-faced king surrounded by industrious Makers, all busily decorating him with magnificent accessories.

“Oh, King Henry was rather naughty.” Great-aunt Petronella sighed, gazing up at the painting. “I remember, after he beheaded his second wife, my mother made me hide in the garderobe when he came for his fittings. She was worried he’d take a shine to me.”

Cordelia turned to her great-aunt. “But—that was over two hundred years ago!”

“Yes.” Great-aunt Petronella nodded. “I was a pretty young thing, wasn’t I?”

Cordelia walked into the middle of the enormous room, leaving a track of footprints in the dust.

Cordelia stared at the graceful young lady in the painting who was placing an ornately embroidered cap on the king’s head. She turned to study her great-aunt’s parchment-pale face, her wrinkles so deep they could have been carved from marble.

“Great-aunt, exactly how old are you, if I might be permitted to ask?” Cordelia said, careful to sound as polite as she possibly could.

Her great-aunt turned twinkling eyes to Cordelia. “Oh, once I got to a hundred I stopped counting.”

“But when was that?” Cordelia asked.

“Ah, dearest, time is relative, you know!”

Cordelia could not tell whether or not her great-aunt was joking. She turned back to the painting, still puzzling. Then she noticed something else strange about it.

“But—there are six Makers in this picture!” she exclaimed. “Hat—Cloak—Glove—Watch—Boot—and … is that a walking stick?”

“Cane,” her uncle said through a tight jaw. “The Canemakers.”

“Who are the Canemakers? Why are they in this picture? I thought there were only five Maker families!”

“There were six,” Aunt Ariadne admitted, her footsteps echoing as she marched across the great empty chamber. “King Henry appointed six Maker families in total. As well as being vain, he was also paranoid—he constantly worried about his enemies trying to overthrow him and take his throne—so he gave the six greatest Maker families a royal charter and banned all other makers from working.”

“There were other makers?”

“Oh, yes,” Great-aunt Petronella said. “There was once a time when everyone in England was free to make whatever they chose, and not just clothes. Then the king decided he wanted to keep that power all for himself and anyone caught Making anything without a royal charter was thrown in prison.”

“Why?” Cordelia cried.

“The king was afraid that somebody else might invent a hat that would give them great cleverness, or make gloves to gain the upper hand, or a cloak of compelling elegance, and then they would be able to throw him off the throne. He made the six chosen families sign a pledge to do no harm. That’s where the Maker motto comes from: Noli nocere, do no harm.”

“I thought that was the Hatmaker family motto?” Cordelia asked.

Her aunt shook her head. “It belongs to all the Maker families,” she said, ignoring Uncle Tiberius grinding his teeth behind her.

Cordelia frowned. “And … the Canemakers—what happened to them?”

“After King Henry died, we kept on Making,” Great-aunt Petronella said. “All six royal-appointed Maker families would come every day to the Guildhall to Make things for the king or queen. In 1632, King Charles I gave permission for us to Make things for members of the aristocracy. We Made things for the lords and ladies, but always had to keep the most magnificent things for the king himself. That way, he made sure he was always the grandest and most powerful person. Each family of Makers had an individual workshop leading off this grand chamber. That’s the Hatmaking Workshop there—”

She pointed to a tall door with a crest carved over it: a shield with a plume-feathered hat, surrounded by seven stars.

“Oh!” Cordelia was surprised to see the familiar Hatmaker emblem looking perfectly at home in this strange, ancient place.

“Do you know why there are seven stars on the Hatmaker crest?” Aunt Ariadne asked her.

Cordelia shook her head.

“There’s one for each Maker family,” her aunt told her. “And the seventh star represents the idea that the Makers shine brightest when they all work together. You can have a hat, or a pair of gloves, or a cloak, but alone they have less power. The most potent magic is said to ignite when all six Makers unite.”

Uncle Tiberius growled low in his throat and narrowed his eyes at a portrait of a plump Glovemaker smiling benignly from the wall.

“We all shared our secrets and ingredients and new techniques and discoveries very happily,” Great-aunt Petronella told Cordelia. “There was a slight disagreement between the Hatmakers and the Bootmakers in the early 1600s, and a spot of bother in the middle of the century with a chap called Oliver Cromwell. But, generally speaking, generations of Makers got along very well for about two hundred years …” Her great-aunt stopped.

“Then—what happened?” Cordelia asked.

“Thirty years ago … Solomon Canemaker broke the Makers’ pledge.”

“You mean the pledge to do no harm?”

Great-aunt Petronella nodded gravely. “He began secretly Making swordsticks. He would encrust the handles of his canes with jewels and carvings to encourage hot-headedness or excessive pride or vanity, and hide a thin blade inside the cane.”

Cordelia looked around the great room for the Canemaker crest. She saw it, mounted over the door opposite the Hatmakers’ crest: two crossed walking sticks that sharpened into lightning bolts at the bottom.

“He was using Menacing ingredients in his creations,” Great-aunt Petronella said, and Cordelia felt her eyes widen. “Back then, every evil ingredient a Maker found on their travels was locked in the Menacing Cabinet here, at the Guildhall.”

Her great-aunt extended a pale finger and pointed to the far wall. Set into the wood paneling was a tall iron door. Cordelia shuddered: carved into the door was a grinning skull.

“Is it like the Menacing Cabinet at Hatmaker House?” she asked.

“Yes.” Her great-aunt nodded. “But this one is much bigger. And it was locked with six locks—do you see the keyholes?”

Cordelia crept closer to the cabinet. There was a row of six bones beneath the skull, each with a keyhole.

“Each family of Makers was entrusted with a master key, so the Menacing Cabinet could never be opened without everyone’s consent. The purpose of the six keys was to keep the evil ingredients from ever being used.”

Cordelia nodded. The skull stared at her out of empty eye sockets.

“But Solomon Canemaker wanted something different. He went out searching for Menacing ingredients. He collected them secretly. He didn’t tell the other Makers about the wicked things he had plundered from around the world.”

Cordelia turned to her great-aunt. “Why?”

“He was greedy. He wanted everyone in London to own a Canemaker cane. He secretly turned the ingredients into weapons, so that everybody would be frightened of walking around without the protection of their own cane. Perhaps the most dangerous ingredient he used was his own bad intentions: he twisted evil into each swordstick. He Made hundreds before he was caught.”

“How was he caught?”

Great-aunt Petronella’s face clouded.

“A young man was killed,” she said quietly. “He wasn’t much more than a boy, really. His name was Abel Dudlook, youngest son of the Duke of Dudlook. One night young Abel exchanged angry words with the son of a squire, on Piccadilly. Witnesses said the quarrel quickly became a fight. Both boys were carrying Canemaker swordsticks. There was the clunk of wood hitting wood, then a stripe of silver flashed out of one cane, then the other, and within a minute one boy lay dying on the pavement and the other had fled. Both boys, it turned out, had bought their new canes that very day.”

Cordelia was cold with horror. Making had made that happen.

“The Duke would not rest until his son’s murderer was found,” Great-aunt Petronella went on heavily. “The poor foolish boy was discovered and hanged at Newgate. When the Lord Privy Councilor found the swordstick used in the fatal fight, he realized the Canemakers’ treachery. The Canemaker family was stripped of the royal charter and Solomon was branded a traitor and executed on Tower Hill. Mrs. Canemaker and the two children were thrown into a workhouse, penniless and in disgrace. They all died less than a year later. The young Miss Canemaker was a little younger than you are now. It was a terrible tragedy.”

Cordelia gazed at the carved Canemaker crest. There was something chilling about it: something furious about the way the lightning bolts struck down, like vengeance. She thought of the young Canemaker girl—ripped away from the enchanted life she knew and thrown into a dingy, stinking workhouse. And she had died there.

Cordelia shivered with sorrow.

“But why is the Guildhall empty now?” she asked, looking across the abandoned room to the glowing stained-glass window. The window depicted six Makers in Elizabethan clothing holding their creations aloft, but someone had smashed the Canemaker’s face, so the body was creepily headless. “Why did everyone leave, if just the Canemakers were disgraced?”

“Well, dearest, old tensions tend to surface in times of crisis,” her great-aunt said wisely. “Everybody was shocked by what had happened, and emotions were a little raw. Then the Bootmakers accused the Hatmakers of stealing ideas—”

“BAH!” Uncle Tiberius exploded, his voice echoing around the vast chamber. “Those Bootmakers were keeping secrets. And the Cloakmakers weren’t sharing either! The Watchmakers were the first to go. Said they couldn’t hear their precious watches tick, what with other Makers having shouting matches in the grand hall. After them, the Cloakmakers packed up and left. The Glovemakers weren’t far behind. Then it was just Hatmakers and Bootmakers, and we couldn’t stand the sight of those useless—”

“Tiberius!” Aunt Ariadne hissed.

Uncle Tiberius broke off mid-sentence, and Cordelia turned around.

Every Maker in London was standing in the great chamber.