7

1

In July 1764 a striking young woman was sitting at the window of a remote country château in Holland, carefully writing a secret letter. The château – with fairy-tale turrets, a deep moat, and lines of poplar trees stretching to a distant view of canals and windmills – was her family home: the seventeenth-century Castle Zuylen, hidden away deep in the peaceful farmlands near Utrecht.

The young woman was Isabelle de Tuyll, the eldest daughter of the aristocratic de Tuyl de Serooskerken family, governors of Utrecht. The secret letter she was writing was addressed to her newfound confidant, a glamorous Swiss aristocrat and career soldier, the Chevalier Constant d’Hermenches. Isabelle was twenty-three years old, headstrong and unattached. The Chevalier d’Hermenches was married, almost twice her age, and had the reputation of a libertine. He wore a dashing black silk band around his temples, to hide a war wound. Their clandestine correspondence was being smuggled in and out of Castle Zuylen via a compliant Utrecht bookseller.

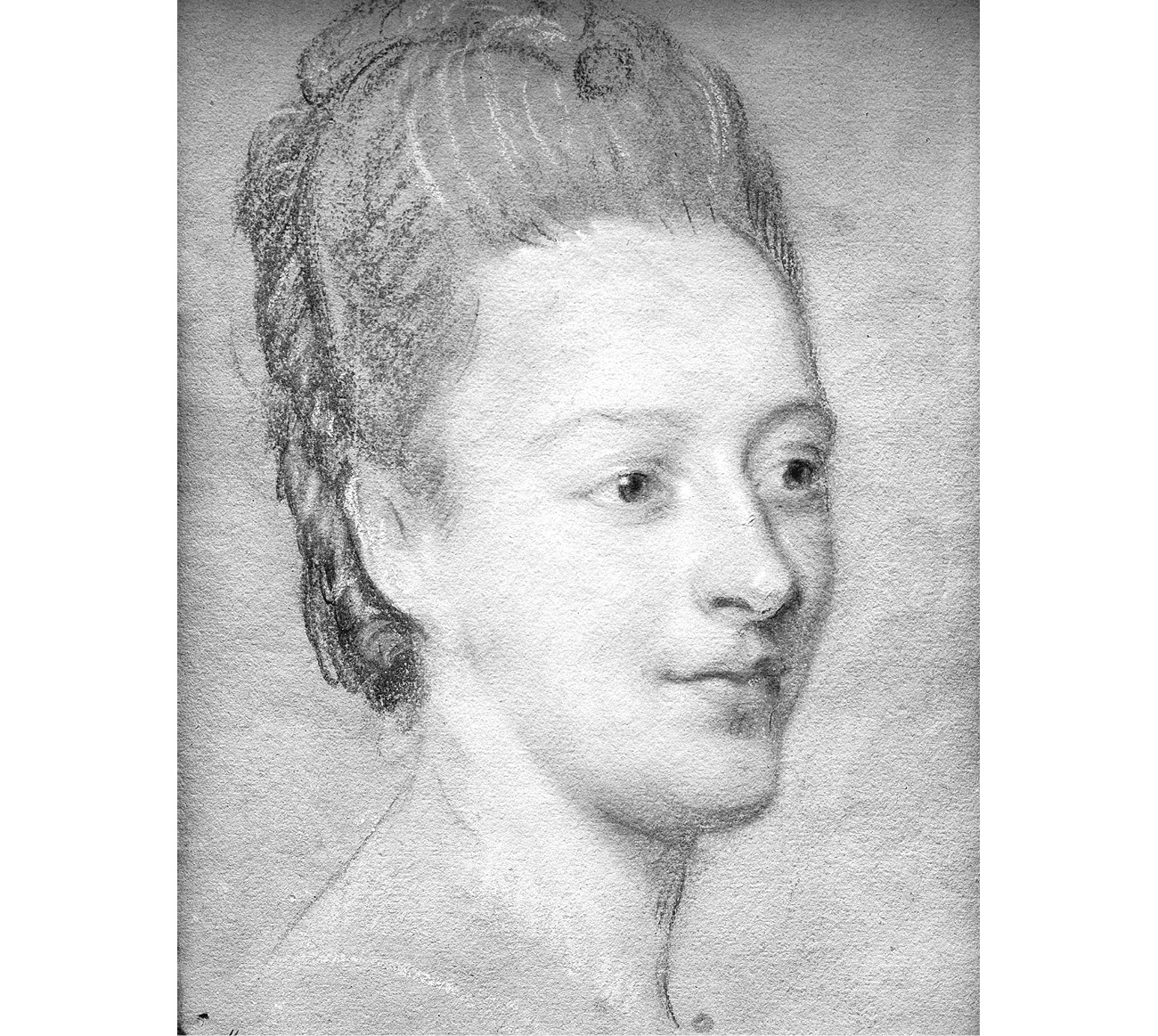

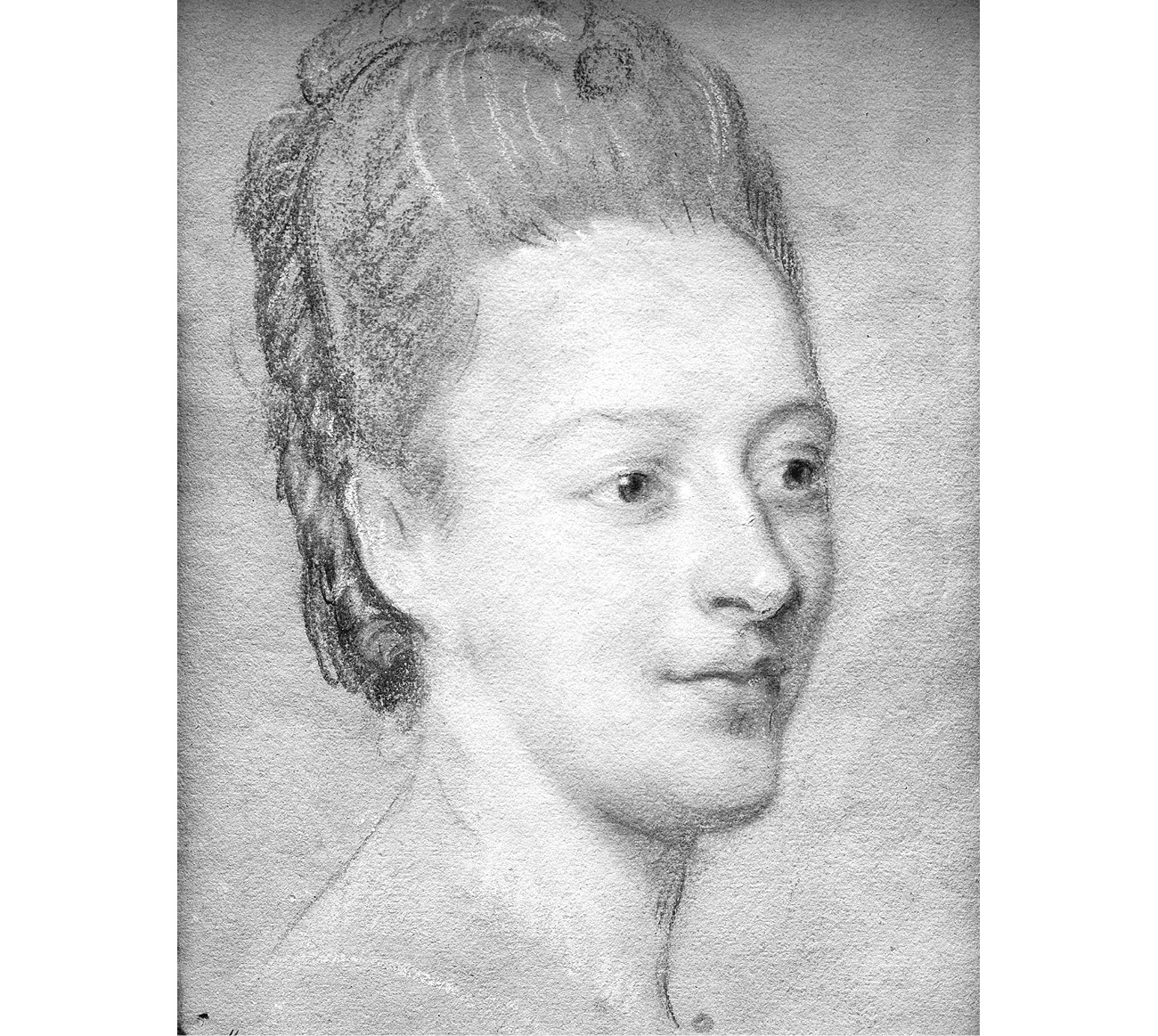

If it was an unusual situation, then Isabelle de Tuyll (known by the local landowners as ‘Belle de Zuylen’) was a thoroughly unusual young woman. While not classically beautiful, she was extremely attractive, and drew glances wherever she went. She had a full, open face, with large green eyes and wild auburn hair brushed impatiently back from a high forehead. She was tall, commanding, full-bosomed, and restless in all her movements. Not only an accomplished harpsichordist (who composed her own music), she was also an expert shuttlecock player, quick and determined in her strokes, with an almost masculine speed and self-confidence.

Isabelle de Tuyll was also unusually well-educated. Her liberal-minded father, recognising the exceptional talents of his eldest daughter, had spared no expense. As a girl she was given a clever young governess from Paris, Mlle Prévost, and was soon studying French, Latin, Greek, mathematics, music, algebra and astronomy. Later she was tutored by a mathematics professor from Utrecht University. She took a particular delight in reading Voltaire and calculating conic sections. She once remarked nonchalantly: ‘I find an hour or two of mathematics freshens my mind and lightens my heart.’

By the time she was twenty in 1760, Isabelle de Tuyll was being besieged by suitors, proving particularly attractive to rich Dutch merchant bankers and penniless German princelings. But she was too quick and clever for most of them. They bored or irritated her. The first time she ever saw the Chevalier d’Hermenches, at the Duke of Brunswick’s ball in The Hague, typically she broke all the rules of etiquette by going straight up to him and asking, ‘Sir, why aren’t you dancing?’ For a moment he was irritated and offended, but was then quickly charmed: ‘At our first word, we quarrelled,’ he said later, ‘at our second, we became friends for life.’ It was soon after that their clandestine correspondence began.

Though Isabelle was admired by her younger siblings (and adored by her brother Ditie), her parents thought of her with increasing anxiety. In the salons of Utrecht and The Hague she was getting the reputation of a belle esprit, an unconventional free spirit, a rationalist, a religious sceptic – in short, a young person of ‘ungoverned vivacity’. This was all very well for a man, but perilous for a young woman. She might never marry and settle down. Her name ‘Belle de Zuylen’ was now spoken with a certain frisson.

As if to confirm these worries, Isabelle began to write poems, stories and essays. In 1762 she published her first and distinctly rebellious short story, ‘Le Noble’, in Le Journal Étranger. It described a young woman eloping with her lover from a moated Dutch castle, under the disapproving gaze of the ancestral portraits. In fact the ancestral portraits are literally stamped underfoot when they are thrown down to form a pontoon bridge over the moat, across which the young woman dashes to freedom one summer night. This work set tongues wagging in Utrecht.

Next, more daring, she wrote and circulated among her friends her own deliberately provocative self-portrait. It was now that, perhaps inspired by Voltaire, Isabelle de Tuyll invented her own literary nom-de-plume: the sinuous, satirical and distinctly sexy ‘Zélide’. (Like Voltaire’s adaptation of his family name, ‘Arouet’, ‘Zélide’ seems to have been based on a sort of loose anagram of her nickname, ‘Bel-de-Z’.)

She described Zélide as follows:

You ask me perhaps is Zélide beautiful? … pretty? … or just passable? I do not really know; it all depends on whether you love her, or whether she wants to make herself lovable to you. She has a beautiful bosom: she knows it, and makes rather too much of it, at the expense of modesty. But her hands are not a delicate white: she knows that too, and makes a joke of it …

Zélide is too sensitive to be happy, she has almost given up on happiness … Knowing the vanity of plans and the uncertainty of the future, she would above all make the passing moment happy … Do you not perceive the truth? Zélide is somewhat sensual. She can be happy in imagination, even when her heart is afflicted … With a less susceptible body, Zélide would have the soul of a great man; with a less susceptible mind, with less acute powers of reason, she would be nothing but the weakest of women.

This delightful tangle of self-contradictions, these ‘feverish hopes and melancholy dreams’, these struggles with role and gender, form the heart of Zélide’s early correspondence with the Chevalier d’Hermenches. They are not exactly love letters. But they are highly personal, intense, and sometimes astonishingly confessional. They also leave room for a great deal of lively discussion of local Utrecht gossip, scandal, marriage schemes, reading, and what Zélide called her ‘metaphysics’. Above all, they discuss the future – what is to become of Zélide?

In her remarkable summer letter of July 1764, Zélide set out two possible and radically different directions for her life. What she is most concerned about – this young woman of the European Enlightenment – is sexual happiness and intellectual fulfilment. The two do not necessarily coincide. She puts two alternatives before the Chevalier d’Hermenches.

First, she could be a sexually ‘independent’ career woman in some great city. For instance, she could model herself on the celebrated Parisian wit and beauty Ninon de Lenclos (1620–1705), live a self-sufficient urban life (Amsterdam, Geneva, London or Paris are all considered), take lovers as it pleased her, write books, keep a literary salon, and develop a circle of trusted and intimate female friends. Or second, she could be a married woman in the country. In this role, not at all to be despised, she could fulfil the wishes of her parents, make a good aristocratic marriage to ‘a man of character’, find emotional security in her family, have children, and look after a large country estate in Holland. This too could be immensely fulfilling, provided only that she found a truly loving and intelligent husband, who ‘valued her affections’, who ‘concerned himself with pleasing her’, and above all, who ‘did not bore her’.

‘You may judge of my desires and distastes,’ she wrote to the Chevalier d’Hermenches. ‘If I had neither a father nor a mother I would be a Ninon, perhaps – but being more fastidious and more faithful than she, I would not have quite so many lovers. Indeed if the first one was truly lovable, I think I might not change at all …’

This possibility sounds like Zélide setting her cap at the Chevalier, a thing that she would often contrive to do. But perhaps she was not entirely serious? She continued: ‘But I have a father and mother: I do not want to cause their deaths or poison their lives. So I will not be a Ninon; I would like to be the wife of a man of character – a faithful and virtuous wife – but for that, I must love and be loved.’

But then, was Zélide entirely serious about marriage either? ‘When I ask myself whether – supposing I didn’t much love my husband – whether I would love no other man; whether the idea of duty, of marriage vows, would hold up against passion, opportunity, a hot summer night … I blush at my response!’ Here was a premonition of the choice that has increasingly faced so many women ever since: career or marriage, freedom or faithfulness, or some daring combination of the two.

The extraordinary fascination of Zélide’s life story lies in how this choice worked out in practice over the next forty years. It was not by any means as she had planned it. She did marry and settle on a country estate, but she never had children, and she was desperately lonely for much of her life. Equally, she did write books, notably the influential and tragic love story Caliste (1787), and the proto-feminist novel Three Women (1795). And she did have her hot summer nights. But she was intellectually isolated, and ended by pouring much of her emotional life into letter-writing. The great social changes of the French Revolution came too late to save her. After her death in 1805, at the age of sixty-five, her books and her story were soon apparently forgotten.

Despite all her determination to direct her own life, Zélide’s destiny was shaped and influenced by four very different men. The first was her older and clandestine correspondent the Chevalier d’Hermenches, a close friend of Voltaire’s, the sophisticated familiar of the Swiss and Paris salons, whose powerful influence – both emotional and literary – lasted until Zélide was past thirty. He was a clever man who understood her very well, but he was also an ambiguous friend, who like Valmont in Les Liaisons Dangereuses (1782) was perhaps ultimately planning to set her up as his mistress. Zélide may have colluded in this, enjoying what she called ‘the salt’ and flattering attention of his witty letters, flirting with him and cooperating in his mad matrimonial schemes (which seemed perilously like propositions of a ménage-à-trois). He may eventually have ruined her chances of making a happy and truly fulfilling marriage.

The second figure is one of the many rather preposterous suitors who were drawn like moths to Castle Zuylen. This was none other than the young Scottish law student, traveller on the Grand Tour, and would-be seducer, James Boswell Esquire. Boswell came to Utrecht in 1763, at the age of twenty-five, shortly after he had first met Dr Johnson in London. He was satisfactorily deep in his own emotional crisis, struggling with manic-depressive episodes: the mania provoking brief, unsatisfactory sexual encounters, and the depression producing long, soothing and reliable assignations with drink.

But amidst all this he was also discovering his true métier as biographer and autobiographer, and keeping his first secret Journals. Thus the encounter with Zélide struck literary sparks, and ignited one of her best and most scintillating correspondences, with Boswell playing the unlikely role of moral tutor. He undoubtedly brought a great deal of fun, charm and frivolity into her life. He even proposed marriage to her (also by letter) in 1768. She turned him down by return of post; rather exquisitely, on strictly literary grounds, since they disagreed on the way to translate a paragraph of his bestselling book about Corsica.

The third was the man she actually married in 1771 – to everyone’s surprise and against everyone’s advice, and to the Chevalier’s acute irritation. Zélide had reached the critical age of thirty. Her suitor was her younger brother’s tutor: the retiring, stammering, genial, thoughtful, but largely silent and singularly unexpressive Charles de Charrière. He took Zélide away to live on his small country estate of Le Pontet, at Colombier on the Swiss border, surrounded by a walled garden and placid vineyards, and with a distant hazy prospect of Lake Geneva.

Here the youthful figure of Zélide largely disappears from view. Her childless marriage was accounted, perhaps wrongly, as a disaster. But the person who re-emerges some fifteen years later is Zélide transformed into the formidable, if disillusioned, Madame Isabelle de Charrière: moralist, social commentator, unquenchable letter-writer, and author of two lengthy epistolary novels, both published in 1784. Letters Written from Neufchâtel is a topical exploration of questions of birth, privilege and social injustice; while Letters from Mistress Henley published by her Friend is a slow, subtle, psychological study of loneliness in marriage.

It is at just this point that the fourth, most unexpected and most unaccountable of all the men in her life appears. He was the young, volatile, red-haired French intellectual Benjamin Constant. Madame de Charrière met him on a rare visit to Paris, either in 1785 or 1786. Now the positions were almost exactly reversed from the Zuylen days with the Chevalier d’Hermenches. Benjamin Constant was twenty, while Zélide was married, worldly-wise and forty-six. Zélide’s influence over her protégé was to last for almost a decade, and to produce the last and most remarkable correspondence of her life. When she was finally supplanted in Constant’s affections, it was by the turbulent figure of Madame de Staël. In many ways this finally brought an end to all Zélide’s hopes and plans, and reduced her in the eyes of the world to a kind of tragic, but dignified, silence.

Yet even after her death in 1805, her influence continued to work powerfully, helping to shape both de Staël’s famous novel of passionate awakenings, Corinne (1807), and Constant’s autobiographical masterpiece Adolphe (1816). It was difficult to say whether Zélide (or Madame de Charrière) had in the end failed or succeeded in her life’s plan. Or perhaps it was simply too soon to draw an informed conclusion.

2

That question, like Zélide herself, was largely forgotten for more than a hundred years. Almost everything except her love story Caliste fell out of fashion and out of print. Despite the presence of both Boswell and Constant in her story, neither French nor English biographers of the nineteenth century were much interested in the lives of women of this period, unless they were saints or strumpets, or somebody’s sister, or Joan of Arc or Queen Victoria. Sainte-Beuve alone considered her worthy of a short essay, commending Zélide for writing fine aristocratic French prose ‘in the manner of Versailles’, but mocking her infatuation with Constant.

But in 1919 Zélide found an unlikely champion. A young English architectural historian, Geoffrey Scott, was visiting Ouchy on Lake Geneva, and one rainy autumn afternoon he discovered copies of Zélide’s books in the Lausanne University library. He was so struck by the paradoxes of her story, and certain resonances it had with his own complicated emotional life, that he began an intensive period of research, reading all her novels, visiting Zélide’s estate at nearby Colombier, and digging out her unpublished letters. Scott later wrote: ‘Today a sentimental journey to her home at Le Colombier, which thrilled me. There is a little secret staircase concealed in cupboards connecting her room with the one Benjamin used to have, which would be amusing … [Madame de Staël’s Château de] Coppet I also loved. Altogether I’ve fallen under the charm of these shores.’

Early in his research Scott unearthed a rare two-volume study of Zélide’s work, Madame de Charrière et ses Amis, published in a limited edition in Geneva in 1906. This remarkable book was a labour of love, which had been minutely compiled over a lifetime by a local Swiss historian of Neufchâtel, Philippe Godet. Godet might be described as the last of Zélíde’s protégés. He wrote tenderly in his Preface: ‘Twenty years ago I fell in love with Madame de Charrière and her work … for twenty years writing her biography has been my ruling passion … and for those twenty years I have been gently mocked by my friends for the childish minuteness and unbelievable slowness of my researches.’

These two vast, shapeless, erudite, pedantic and loving tomes proved an added incitement to Scott’s natural, and distinctly dandyish, sense of aesthetic form. He immediately set out to write exactly the opposite kind of biographical study of Zélide: a brief, elegant, highly stylised and distinctly sardonic ‘portrait’, partly inspired by the recent success of Lytton Strachey’s Eminent Victorians (1918), which had risked one controversial account of a woman – that of Florence Nightingale. ‘Perfect as workmanship,’ enthused Scott, ‘a book in ten thousand.’

Geoffrey Scott was greatly intrigued by Zélide’s intense and unusual relationships, first with the Chevalier d’Hermenches and then with Constant. It turned out that they were uncle and nephew, and they offer to the biographer a tempting – though coincidental – symmetrical shape to Zélide’s life, providing portraits to be ‘hung on either side’ of hers. In fact Scott (following Sainte-Beuve) deliberately gave most weight to the affair with Constant, so that the period of seven years when it flourished (1787–1794) actually occupies over half of his book. Yet this produces a psychological drama of such interest, told with such an engaging mixture of tenderness and malice, that the reader is barely aware of the skilful foreshortening involved. Scott explores the emotional significance of the age gap, the curious sexual currents behind their voluminous literary correspondence, their obsession with ‘frankness and sincerity’, and the profound intellectual impact of each upon the other.

He has a shrewd and witty awareness, so essential to the biographer, of the haunting difference between the written document and the lived life:

It may confidently be asserted that the habit of letter-writing has estranged far more lovers than it has united … To dip the quill in ink is a magical gesture: it sets free in each of us a new and sometimes a forbidding sprite, the epistolary self. The personality disengaged by the pen is something apart and often ironically diverse from that other personality of act and speech. Thus in the correspondence of lovers there will be four elements at play – four egoisms to be placated instead of two. And by this grim mathematical law the permutations of possible offence will be calculably multiplied.

Yet the biography never becomes laboured or abstract. Scott always envisaged Zélide’s life in sharp, architectural outline, and executed this with wonderful graphic effects. He also viewed it sceptically. He presented the brief interlude with Boswell as high comedy, and the long marriage to Charles de Charrière as a relentless matrimonial satire, while the final irruption of Germaine de Staël in her daemonic coach on the road to Lausanne, at the opening of Chapter 13, is described with something approaching Gothic melodrama. De Staël’s ‘black and burning gaze’ glares out fatally through the carriage window into Zélide’s story.

Above all, Scott saw Zélide’s determination to choose her own life, her own destiny, in the face of eighteenth-century social conventions, as both the crux of the biography and the source of its ‘unadmitted but evident tragedy’. For Scott this was a terrible if heroic error, with the result that Zélide ‘failed, immensely and poignantly’ in her search for happiness.

This, at any rate, is the challenging note on which the biography opens. It is a proposition taken from Benjamin Constant, the young intellectual enchanter, and the male figure in the story with whom Scott most closely identified. Constant later wrote of Zélide in Adolphe: ‘Like so many others this woman had begun her career by sailing forth to conquer society, rejoicing in the possession of moral toughness and a powerful mind. But she did not understand the ways of the world and, again like so many others, through failing to adapt herself to an artificial but necessary code of behaviour, she had lived to see her progress disappointed and her youth pass joylessly away until, finally, old age overtook her without subduing her.’ This was exactly what Scott, as Zélide’s first modern English champion and biographer, apparently concluded of his heroine too.

Yet Geoffrey Scott’s personal identification with his material was far greater than at first appears. It is partly this that makes the biography so subtly engaging and self-contradictory. Far from producing a coolly objective study of Zélide, the deliberately polished ‘studio portrait’ that he claimed, Scott was writing something perilously close to autobiography. This too makes the biography peculiarly modern in its shifting layers of symbolism and self-reflection.

For the previous decade (and through most of the First World War) Scott had been working as the personal assistant of the celebrated art historian Bernard Berenson, comfortably housed in his vast Florentine villa, I Tatti. Here Scott cultivated an intense platonic relationship with Berenson’s wife Mary, twenty years his senior, and upon whom he had become emotionally dependent.

Scott – handsome, clever and dilettantish (he had won the Newdigate Prize for poetry at Oxford) – could be devastatingly charming. But he was also disorganised, spoilt, selfish and decidedly rakish. In an effort to break away from Mary he embarked on a number of affairs, both platonic and otherwise: one with Berenson’s young assistant Nicky Mariano, another with the elderly Edith Wharton in Paris. Then in 1918 he suddenly and unexpectedly married Mary Berenson’s great friend, the aristocratic and neurasthenic Lady Sybil Cutting, who also had a grand house in Florence, the Villa Medici.

The marriage almost immediately ran into difficulties. Ironically, it was only held together (according to Lady Sybil’s daughter, the writer Iris Origo) by their mutual interest in Zélide, discovered that autumn of 1919 on the shores of Lake Geneva, where Scott had taken Lady Sybil on a rest cure. Origo later wrote in her memoir Images and Shadows: ‘Thus by a curious irony, a woman [Zélide] whose own emotional life had been singularly unhappy, brought for a few months, harmony to another woman’s marriage. In the absorption of bringing Zélide and Boswell, d’Hermenches and Constant, to life again, Geoffrey and his wife suspended the relentless analysis of their own feelings; they laughed and worked together. Perhaps, too, there was in all this a certain process of self-identification.’

After the initial excitement of discovery, Scott’s work on the biography, which he had intended to finish in a year, slowed down. Like Philippe Godet, he underwent the classic ‘transfer experience’ of the modern biographer, starting as the detached scholar but gradually being drawn hypnotically into all the domestic details and dramas of Zélide’s world. As a result the historical story became increasingly an unsettling reflection of his own life and emotional entanglements.

In 1922 Scott wrote to Nicky Mariano: ‘The thing that makes me stick in the mud with the book, is that [Zélide’s] relations with Benjamin Constant, after his marriage, have an uncanny likeness to Mary [Berenson]’s feelings and actions four years ago. I understand it almost too well to write about it in the detached and light manner which the tone of the book requires … The idea of Mary’s reading the manuscript and drawing the inevitable parallels at each point embarrasses me a good deal in writing it.’

When not working on Zélide, Scott drifted away from Lady Sybil and his marriage. He spent the summer of 1923 in England, and embarked on a refreshing new affair, this time with Harold Nicolson’s wife, the aristocratic novelist Vita Sackville-West. Vita was another powerful literary woman with a country estate, the beautiful manor house of Long Barn in Kent (near her ancestral home of Knole). As an established writer she too encouraged Scott with his work on Zélide. He could confide in her without ceremony, and revealed his increasingly intense involvement with Zélide’s story.

‘I’m going to busy myself this week with Madame de Charrière,’ he wrote to Vita in October 1923. ‘I’ve dragged her by the scruff of the neck round two or three difficult corners. I’ve done the meeting with Benjamin and the first fantastic part of their friendship: it’s good that part, I hope, and goes with a swing. I give it mostly through Monsieur de Charrière’s eyes, bewildered and misunderstanding, watching rather breathlessly the spectacle of Zélide coming back to life. I’ve got Mme de Staël in the wings just ready to pop in … with her private theatricals, negroid beauty, her tramping insensibility and impeccable bad taste.’

He emphasised the daring speed he had set himself in the narrative: ‘I’ve struck a very quick tempo, and can’t afford now to slow it: the book will be quite shockingly short.’ But above all he stressed his personal excitement with the work, and the way he was now inspired by Vita: ‘It’s fun, though, doing it. I do it for you.’

So the tangled web of Geoffrey Scott’s relationships (not in fact unduly tangled by the standards of post-war Bloomsbury) generated an extensive correspondence about the biography, and curiously mimicked different aspects of Zélide’s own story. Mary Berenson, Edith Wharton, Lady Sybil and Vita Sackville-West were each separately told by Scott that the biography was secretly and lovingly dedicated to them alone, and contained their own ‘portrait’ lovingly disguised as Zélide’s.

Similarly, it was to be understood that Scott himself was sometimes the mercurial Constant, sometimes the worldly Chevalier d’Hermenches, and sometimes (though rarely) the long-suffering and inadequate M. de Charrière. On the other hand, he was never James Boswell. Mostly he identified with Benjamin Constant, writing to Mary Berenson that drawing Constant’s portrait gave him the most trouble: ‘he is so many sided, so inexhaustible, it is difficult to bring him out fully within the compass of my small scale’.

3

Far from softening or sentimentalising the texture of the biography, this secret shimmer of subjectivity gives it an almost unnatural sharpness and stylistic brightness. From the opening Scott makes brilliant metaphoric use of the pastel portrait of Zélide by Maurice-Quentin de la Tour, and the contrasting monotonies of Dutch landscape – and society – stretching behind her. The whole book has a strong visual sense, and Scott continually presents Zélide’s moods in terms of beautifully conjured landscapes or interiors. It is in effect a series of Dutch still lives.

Yet just as he planned, he moves the narrative forward at a dazzling pace, compressing and summarising the story, foreshortening perspective, and playing off the immobility of Zélide’s life at Zuylen and Colombier against the frantic gyrations of Boswell or Constant. The arrival and departure of flying carriages in clouds of dust form a choric motif. This reaches its apotheosis in the fatal appearance of the carriage of Madame de Staël, which intercepts Constant in 1794: ‘A hazy light quivers over the stretched lake of Geneva, on and on, monotonously. A carriage has halted by the wayside near Nyon, in the dust of a September afternoon. Through the window a lady, dressed in black, has looked out. Her black and burning gaze inspects the lanky figure of a young man striding on the Lausanne road …’

Scott’s whole attitude to Zélide is complex, shifting, and unexpectedly contradictory. From the outset he has pronounced her life a tragedy, yet he cannot prevent himself treating it gallantly, humorously, and even at times romantically. In fact, one suspects that he is always in two minds about Zélide, and that part of him is always in love with her. The most beautiful and memorable images in the book are always dedicated to her: ‘So Zélide lay, lost to the world, like a bright pebble on the floor of the Lake of Neufchâtel.’

Yet he ignores or distorts several elements in her story. He underplays the significance of her published writing (apart from its autobiographical aspect), and fails to see the importance of the later work for the feminist canon, notably the brilliantly plotted moral fable Three Women (1795). It is difficult to recall that Zélide was also the author of twelve short novels, twenty-six plays, several opera libretti, and much harpsichord music as well. Nor does he connect her extensive output with younger English writers addressing similar themes, like Mary Wollstonecraft, Amelia Opie or Fanny Burney. But this, perhaps, is a failure of historical rather than biographical perspective.

It is more problematic that Scott does not appear to sympathise – or should one say empathise – with what Zélide called the difficulties of having a woman’s ‘susceptible body’. He does not seem to allow sufficiently for the devastating effect of her inability to have children with M. de Charrière, or relate this to her clandestine affair with a handsome but anonymous young man in Geneva sometime in 1784–85 (his identity still unknown to this day). Zélide was then in her mid-forties, feeling life slipping away, and was perhaps making her one last serious attempt to act like Ninon de Lenclos. As Benjamin Constant subsequently pointed out, this episode was perhaps Zélide’s only real adulterous entanglement, and produced her masterpiece, Caliste (1787).

Above all, perhaps, Geoffrey Scott undervalues the happiness that her last circle of young women friends and protégées brought her after 1790, when she was fifty. They included the flirtatious and incorrigibly pregnant maid Henriette Monarchon, the handsome and talented Henriette l’Hardy (who became her literary executor), the dazzlingly beautiful Isabelle de Gélieu, the clever, sophisticated Caroline de Sandoz-Rollin, and the ‘wild, gorgeous, defiant’ sixteen-year-old Suzette du Pasquier.

These produced Zélide’s own kind of salon des dames at Colombier, and exchanges of letters, poems and confidences quite as full as her masculine ones. Such a circle was, after all, part of Zélide’s original plan to consecrate her life to friendship as well as love. And who is to say that some of these young women, with their new independent ways, did not bring Zélide love as well as friendship?

For all these limitations of sympathy and perspective, Geoffrey Scott’s biography remains a subtle triumph, and a considerable landmark. It changed forever the way English biographers wrote (or failed to write) about women. It recognised that women’s lives had different shapes from men’s, different emotional patterns of achievement and failure. It stressed the value of a psychological portrait over a mere chronology, but never descended to (then fashionable) Freudian reductionism. It suggested that from a woman’s perspective, the very idea of ‘destiny’ was different. Zélide was both subject to men’s careers within the existing frame of eighteenth-century conventions, and yet always, stubbornly and subversively, independent of them.

The Portrait of Zélide was a deserved success when finally published in 1925. It was widely praised by the reviewers, the Times Literary Supplement remarking that it was ‘a biography as acute, brilliant and witty as any that has appeared in recent years’. Edmund Gosse in the Sunday Times added Scott to the group of ‘three or four young writers’ (including Strachey) who had put to flight the ‘wallowing monsters’ of Victorian biography, through ‘delicacy of irony, moderation of range, refinement and reserve’. The book won the James Tate Black Memorial Prize, and ran to three editions in the next five years. Scott himself had the odd experience of appearing in the Vogue Hall of Fame for 1925.

Not surprisingly, there were different reactions from within his own literary circle. Mary Berenson and Edith Wharton loyally praised the book, Wharton greeting it as ‘an exquisite piece of work’. But Vita Sackville-West, perhaps inspired by her new passion for Virginia Woolf, felt it was too flippant, too flashy, and not sympathetic enough to Zélide as a woman writer. Francis Birrell, the voice of Bloomsbury, writing in The Nation, gently reproached it as ‘very readable … fashionable, cosmopolitan, and a trifle over-painted’. Years later Harold Nicolson, Vita’s husband, described it with masterful ambiguity as a ‘delicate biography’.

Nonetheless, it remains a memorable prologue to the full opening up of women’s biography in the twentieth century. It is an early attempt to recover the importance of the woman writer’s role in the culture of Europe, and particularly in the long and rich tradition of Dutch humanism. The early writings of Zélide represent a vivid response to Voltaire and his contes philosophiques. The emotional confrontation between Zélide (or rather Madame de Charrière) and Madame de Staël, and the consequent battle for Benjamin Constant’s soul, is brilliantly deployed by Scott to sum up the intellectual confrontation between Enlightenment and Romantic values. Raymond Mortimer saw this as one of the book’s most original features, the picture of ‘a conflict between two centuries, two states of mind, almost one might say, two civilizations’. He also added shrewdly: ‘[Scott] is a little in love with Madame de Charrière, and so are you, before the book is done.’

Many of these judgements have proved remarkably perceptive. It is now becoming clear that Scott’s work forms part of the 1920s’ revolution in British biography, championing a briefer, more stylish and more inventive form. His Portrait of Zélide needs to be set beside Strachey’s Queen Victoria (1921), André Maurois’s Ariel, ou la Vie de Shelley (1925) and Harold Nicolson’s Some People (1927). Scott himself put his claim modestly, but very well, in a note appended to the end of the book. He first gives full acknowledgement to the faithful, plodding, heroic scholarship of Philippe Godet, and then adds: ‘All I have here done is to catch an image of her in a single light, and to make from a single angle the best drawing I can of Zélide, as I believe her to have been. I have sought to give her the reality of fiction; but my material is fact.’