9

1

It is often said that William Godwin’s Memoirs of the Author of a Vindication of the Rights of Woman of 1798 destroyed Mary Wollstonecraft’s reputation for over a hundred years. If that is true, it must count as one of the most dramatic, as well as the most damaging, works of biography ever published.

At the time of her death in London on 10 September 1797, Mary Wollstonecraft was certainly well-known and widely admired as an educational writer and champion of women’s rights. She was renowned not only in Britain, but also in France, Germany and Scandinavia (where her books had been translated), and in newly independent America. Although only thirty-eight years old, she was already one of the literary celebrities of her generation.

The Gentleman’s Magazine, a solid, large-circulation journal of record with a conservative political outlook, printed the following obituary in October 1797, with an admiring – if guarded – summary of her career and an unreservedly favourable estimate of her character:

In childbed, Mrs Godwin, wife of Mr. William Godwin of Somers-town; a woman of uncommon talents and considerable knowledge, and well-known throughout Europe by her literary works, under her original name of Wollstonecraft, and particularly by her Vindication of the Rights of Woman, 1792, octavo.

Her first publication was Thoughts on the Education of Daughters, 1787 … her second, The Rights of Man, 1791, against Mr. Burke on the French Revolution, of the rise and progress of which she gave an Historical and Moral View, in 1794 … her third, Elements of Morality for the Use of Children, translated from the German, 1791 … her fourth, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, 1792 … her fifth, Letters Written during a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark, 1796.

Her manners were gentle, easy and elegant; her conversation intelligent and amusing, without the least trait of literary pride; or the apparent consciousness of powers above the level of her sex; and for soundness of understanding, and sensibility of heart, she was perhaps, never equalled. Her practical skill in education was even superior to her speculations upon that subject; nor is it possible to express the misfortune sustained, in that respect, by her children. This tribute we readily pay to her character, however adverse we may be to the system she supported in politicks and morals, both by her writing and practice.

Many other favourable articles appeared, such as her friend Mary Hays’s combative obituary in the Monthly Magazine, which lauded her ‘ardent, ingenuous and unconquerable spirits’, and lamented that she was ‘a victim to the vices and prejudices of mankind’. The Monthly Mirror praised her as a ‘champion of her sex’, and promised an imminent biography, though this did not appear. Friends in London, Liverpool, Paris, Hamburg, Christiania and New York expressed their shock at her sudden departure, one of the earliest premature Romantic deaths of her generation. It seemed doubly ironic that the champion of women’s rights should have died in childbirth.

William Godwin, her husband, was devastated. They had been lovers for little over a year, and married for only six months. At forty-one he also was a literary celebrity, but of a different kind from Mary. A shy, modest and intensely intellectual man, he was known paradoxically as a firebrand philosopher, the dangerous radical author of An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice (1793) and the political thriller-novel Caleb Williams (1794). His views were even more revolutionary than hers. He proposed republican, atheist and anarchist ideas, attacking many established institutions, such as private property, the Church, the monarchy and (ironically) marriage itself – ‘that most odious of monopolies’. Indeed he was notorious for his defence of ‘free love’, and their marriage in March 1797 had been the cause of much mirth in the press. Yet Godwin believed passionately in the rational power of truth, and the value of absolute frankness and sincerity in human dealings.

He was in a state of profound shock. He wrote bleakly to his oldest friend and confidant, the playwright Thomas Holcroft, on 10 September 1797, the very evening of her death: ‘My wife is now dead. She died this morning at eight o’clock … I firmly believe that there does not exist her equal in the world. I know from experience we were formed to make each other happy. I have not the least expectation that I can now ever know happiness again. When you come to town, look at me, talk to me, but do not – if you can help it – exhort me, or console me.’

Another of Godwin’s friends, Elizabeth Fenwick, wrote two days later to Mary’s younger sister, Everina Wollstonecraft, in Dublin: ‘I was with [Mary] at the time of her delivery, and with very little intermission until the moment of her death. Every skilful effort that medical knowledge of the highest class could make, was exerted to save her. It is not possible to describe the unremitting and devoted attentions of her husband … No woman was ever more happy in marriage than Mrs. Godwin. Whoever endured more anguish than Mr. Godwin endures? Her description of him, in the very last moments of her recollection was, “He is the kindest, best man in the world.”’ Mrs Fenwick added thoughtfully, and perhaps tactfully: ‘I know of no consolation for myself, but in remembering how happy she had lately been, and how much she was admired, and almost idolized, by some of the most eminent and best of human beings.’

To take advantage of this surge of interest and sympathy across the literary world, Wollstonecraft’s lifelong friend and publisher, Joseph Johnson, proposed to Godwin an immediate edition of her most recent writings. This was to include her long, but unfinished, novel Maria, or The Wrongs of Woman, which had a strong autobiographical subtext. It was a shrewd idea to provide a fictional follow-up to Mary’s most famous work of five years previously, The Rights of Woman. The two titles cleverly called attention to each other: ‘The Rights’ reinforced by ‘The Wrongs’.

Though unfinished, The Wrongs of Woman: A Fragment in Two Volumes contained a celebration of true Romantic friendships, and a blistering attack on conventional marriage. The narrator Maria’s husband has had her committed to a lunatic asylum, having first brought her to court on a (false) charge of adultery. The judge’s summary of Maria’s case, which comes where the manuscript breaks off, ironically encapsulates many of the male prejudices that Mary Wollstonecraft had fought against all her life:

The judge, in summing up the evidence, alluded to the fallacy of letting women plead their feelings, as an excuse for the violation of the marriage-vow. For his part, he had always determined to oppose all innovation, and the new-fangled notions that encroached on the good old rules of conduct. We did not want French principles in public or private life – and, if women were allowed to plead their feelings, as an excuse or palliation of infidelity, it was opening a flood-gate for immorality. What virtuous woman thought of her feelings? – it was her duty to love and obey the man chosen by her parents and relations …

Johnson also suggested that Godwin should include some biographical materials. The idea for a short memorial essay by Mary’s husband was mooted, as was the convention in such circumstances; and possibly a small selection from her letters.

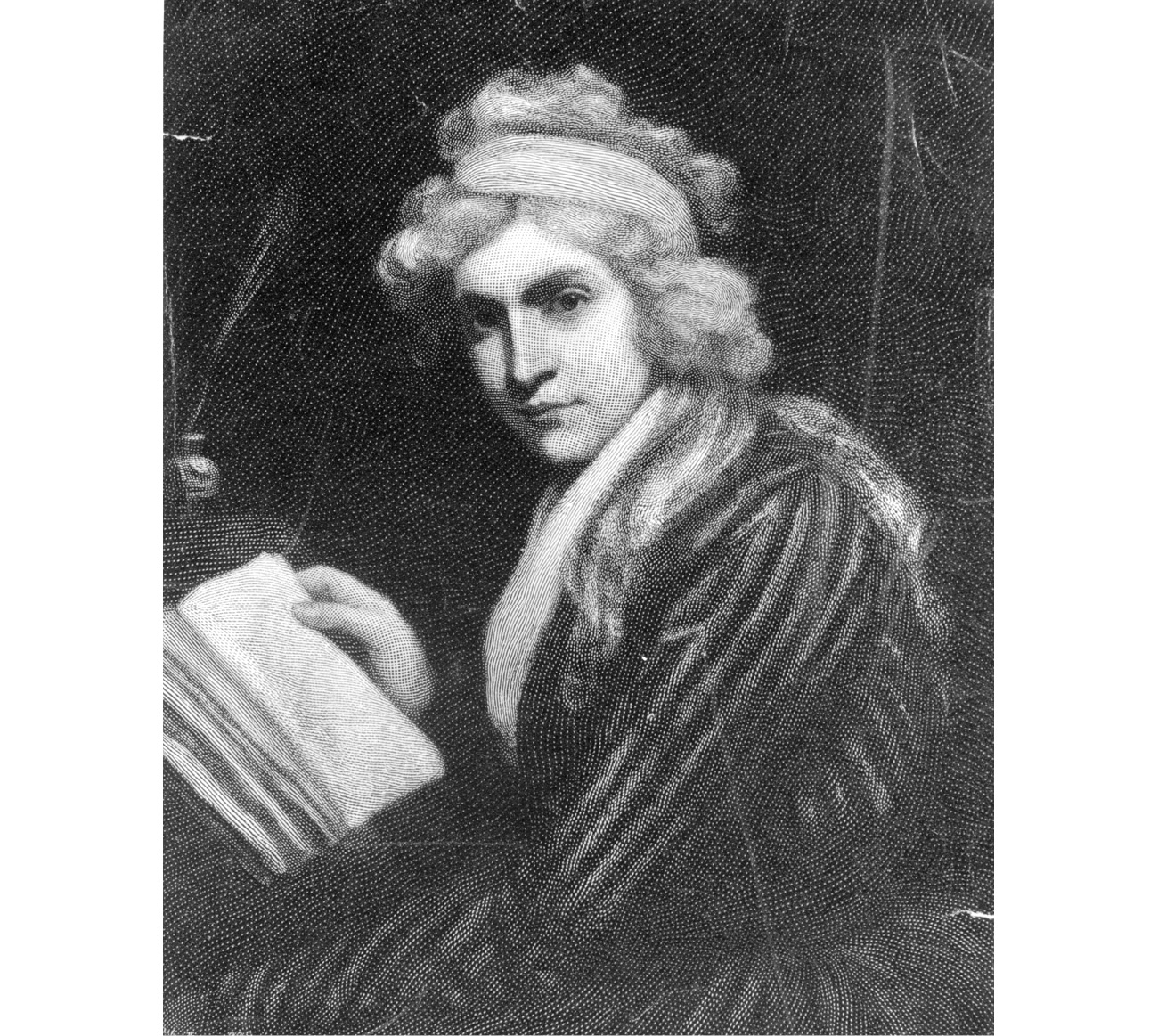

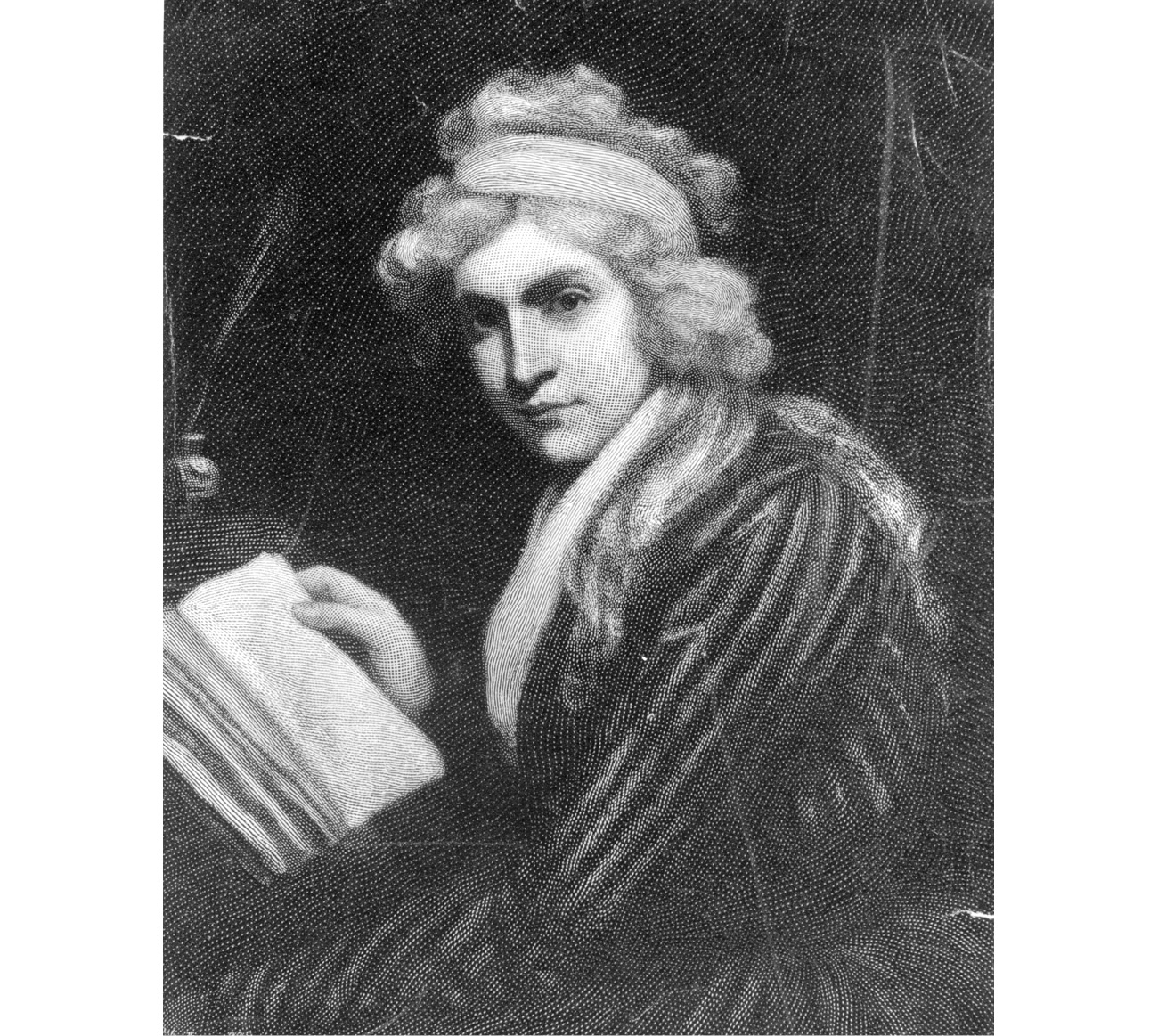

Battling against his grief, Godwin determined to do justice to his wife by editing her Posthumous Works. Immediately after the funeral on 15 September he moved into Mary’s own study at number 29 Polygon Square, surrounded himself with all her books and papers, and hung her portrait by John Opie above his desk for inspiration. He hired a housekeeper, Louisa Jones, to look after the two children who were now his responsibility: the little motherless baby Mary (the future Mary Shelley); and four-year-old Fanny, who was Wollstonecraft’s earlier love child by an American, Gilbert Imlay.

Both as a father and as an author, Godwin regarded himself as fulfilling a sacred trust, and wrote: ‘It has always appeared to me, that to give the public some account of a person of eminent merit deceased, is a duty incumbent on survivors … The justice which is thus done to the illustrious dead, converts into the fairest source of animation and encouragement to those who would follow them in the same career.’

2

Godwin immersed himself in papers and memories for the next three months, and writing at speed, soon found that the short essay was expanding into a full Life. He turned all his cool, scholarly methods on the supremely emotional task in hand. He reread all Mary’s printed works, sorted her unpublished manuscripts, and established a precise chronology of her life from birth. He dated and meticulously numbered the 160 letters they had exchanged. He interviewed her friends in London like Johnson, and wrote to others abroad, like Hugh Skeys in Ireland. He sent diplomatic messages to her estranged sister Everina in Dublin, requesting family letters and reminiscences. He assembled his own journal notes of their intimate conversations, and lovingly reconstructed others, such as the long September day spent walking round the garden where she had grown up near Barking, in Essex. Here Mary had suddenly begun reminiscing about her childhood.

Godwin recalled the moment tenderly, but with characteristic exactitude:

In September 1796, I accompanied my wife in a visit to this spot. No person reviewed with greater sensibility, the scenes of her childhood. We found the house uninhabited, and the garden in a wild and ruinous state. She renewed her acquaintance with the market-place, the streets, and the wharf, the latter of which we found crowded with activity.

Godwin determined to tell each phase of Mary’s short but turbulent life with astonishing openness. This was a decision that stemmed directly from the philosophy of rational enquiry and sincerity enshrined in Political Justice. He would use a plain narrative style and a frank psychological appraisal of her character and temperament. He would avoid no episode, however controversial.

He would write about the cruelty of her father (still living); the strange passionate friendship with Fanny Blood; the overbearing demands of her siblings; her endless struggles for financial independence; her writer’s blocks and difficulties with authorship; her enigmatic relationship with the painter Henry Fuseli; her painful affair with the American Gilbert Imlay in Paris; her illegitimate child Fanny; her two suicide attempts; and finally their own love affair in London, and Mary’s agonising death. This would be a revolutionary kind of intimate biography: it would tell the truth about the human condition, and particularly the truth about women’s lives.

As the biography expanded, Godwin’s contacts and advisers began to grow increasingly uneasy. Everina Wollstonecraft wrote anxiously from Dublin, expressing reservations. She had been delighted at her clever elder sister’s literary success, and been helped financially by it. But it now emerged that she had quarrelled with Mary after her Paris adventures, and disapproved of the marriage to Godwin. She had not been properly consulted by him, and feared personal disclosures and publicity. In a letter of 24 November 1797, she abruptly refused to lend Godwin any of the family correspondence, and informed him that a detailed biographical notice would be premature. She implied that it would damage her (and her younger sister Elizabeth’s) future prospects as governesses:

When Eliza and I first learnt your intention of publishing immediately my sister Mary’s Life, we concluded that you only meant a sketch … We thought your application to us rather premature, and had no intention of satisfying your demands till we found that [Hugh] Skeys had proffered our assistance without our knowledge … At a future date we would willingly have given whatever information was necessary; and even now we would not have shrunk from the task, however anxious we may be to avoid reviving the recollections it would raise, or loath to fall into the pain of thoughts it must lead to, did we suppose it possible to accomplish the work you have undertaken in the time you specify.

Everina concluded that a detailed Life was highly undesirable, and that it was impossible for Godwin to be ‘even tolerably accurate’ without her help. On reflection, Godwin decided to ignore these family objections. He judged them to be inspired partly by sibling jealousy, partly by the sisters’ desire to control the biography for themselves, but mostly by unreasonable fear of the simple truth.

Other sources proved equally recalcitrant. Gilbert Imlay had disappeared with an actress to Paris, and could not be consulted. He had not seen Mary for over a year, though he had agreed to set up a trust in favour of his little daughter Fanny. When this was not forthcoming, Godwin officially adopted her. Godwin felt that it was impossible to understand Mary’s situation without telling the whole story, and now took the radical decision to publish all her correspondence with Imlay, consisting of seventy-seven love letters written between spring 1793 and winter 1795. He convinced Johnson that these Letters to Imlay should occupy an additional two volumes of the Posthumous Works, bringing them to four in total. His Memoirs would now be published separately, but would also quote from this correspondence, openly naming Imlay.

The Letters gave only Mary’s side of the correspondence, which Imlay had returned at her request. They thus left his own attitude and behaviour to be inferred. But they dramatically revealed the whole painful sequence of the affair from Mary’s point of view, from her initial infatuation with Imlay in Paris to her suicidal attempts when he abandoned her in London. This was another daring, not to say reckless, publishing decision which sacrificed traditional areas of privacy to biographical truth. Godwin’s own feelings as a husband were also being coolly set aside. In his Preface he described the Letters as ‘the finest examples of the language of sentiment and passion ever presented to the world’, comparable to Goethe’s epistolary novel of Romantic love and suicide The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774). They were produced by ‘a glowing imagination and a heart penetrated with the passion it essays to describe’.

Henry Fuseli briefly and non-committally discussed Mary with Godwin, but having given him a tantalising glimpse of a whole drawer full of her letters, refused to let him see a single one. If he knew of Godwin’s intentions with regard to Mary’s letters to Imlay, this is hardly surprising. But it left the exact nature of their relationship still enigmatic. Years later the Fuseli letters were seen by Godwin’s own biographer, Kegan Paul, who claimed that they showed intellectual admiration, but not sexual passion. Yet when these letters were eventually sold to the Shelley family (for £50), Sir Percy Shelley carefully destroyed them, unpublished, towards the end of the nineteenth century.

Joseph Johnson was torn between a natural desire to accede to Godwin’s wishes as the grieving widower, and his own long-standing professional role of defending Mary’s literary reputation. He may also have entertained the very understandable hope of achieving a publishing coup. He at least warned Godwin of several undiplomatic references to living persons in the biography, especially the aristocratic Kingsborough children to whom Mary had been a governess in Ireland, and the powerful and well-disposed Wedgwood family. He also questioned the wisdom of describing Mary’s many male friendships in London, Dublin and Paris so unguardedly. He felt the ambiguous account of Fuseli was particularly ill-judged, and challenged Godwin’s characterisation of the painter’s ‘cynical’ attitude towards Mary.

But Godwin would not give way on any of these issues. On 11 January 1798, shortly before publication, he wrote unrepentantly to Johnson, refusing to make any last-minute changes: ‘With respect to Mr Fuseli, I am sincerely sorry not to have pleased you … As to his cynical cast, his impatience of contradiction, and his propensity to satire, I have carefully observed them …’ He added that, in his view, Mary had actually ‘copied’ these traits while under Fuseli’s influence in 1792, and this was a significant part of her emotional development. He was committed to describing this ‘in the sincerity of my judgement’, even though it might sometimes be unfavourable to her.

This idea that Mary Wollstonecraft’s intellectual power grew out of a combination of emotional strengths and weaknesses was central to Godwin’s notion of modern biography: ‘Her errors were connected and interwoven with the qualities most characteristic of her genius.’ He was not writing a pious family memorial, or a work of feminist hagiography, or a disembodied ideological tract. He felt he could sometimes be critical of Mary’s behaviour, while always remaining passionately committed to her genius. Godwin stuck unswervingly to his belief in the exemplary value of full exposure. The truth about a human being would bring understanding, and then sympathy: ‘I cannot easily prevail on myself to doubt, that the more fully we are presented with the picture and story of such persons as the subject of the following narrative, the more generally shall we feel ourselves attached to their fate, and a sympathy in their excellencies.’

3

Godwin could not have been more mistaken. Most readers were appalled by the Memoirs when they were first published at the end of January 1798. There was no precedent for a biography of this kind, and Godwin’s ‘naïve’ candour and plain speaking about his own wife filled them with horrid fascination.

Mary’s old friend, the radical lawyer and publisher from Liverpool William Roscoe, privately jotted these sad verses in the margin of his copy:

Hard was thy fate in all the scenes of life

As daughter, sister, mother, friend and wife;

But harder still, thy fate in death we own

Thus mourn’d by Godwin with a heart of stone.

The Historical Magazine called the Memoirs ‘the most hurtful book’ of 1798. Robert Southey accused Godwin of ‘a want of all feeling in stripping his dead wife naked’. The European Magazine described the work as ‘the history of a philosophical wanton’, and was sure it would be read ‘with detestation by everyone attached to the interests of religion and morality; and with indignation by any one who might feel any regard for the unhappy woman, whose frailties should have been buried in oblivion’.

The Monthly Magazine, a largely conservative journal, saw Mary as a female Icarus figure, who had burnt out her talents with pride and ambition: ‘She was a woman of high genius; and, as she felt the whole strength of her powers, she thought herself lifted, in a degree, above the ordinary travels of civil communities …’

The most even-handed verdict was that of Johnson’s own Analytical Review, which observed that the biography, though remarkable, lacked intellectual depth. It contained ‘no correct history of the formation of Mrs. G’s mind. We are neither informed of her favourite books, her hours of study, nor her attainments in languages and philosophy.’ Even more pointedly, it noted that anyone who also read the Letters would ‘stand astonished at the fervour, strength and duration of her affection for Imlay’.

These initial criticisms, some written more in sorrow than in anger, and not necessarily bad publicity (at least for Johnson), were soon followed by more formidable attacks. The Monthly Review, previously a supporter of Wollstonecraft’s work, wrote in May 1798 with extreme disapproval of Godwin’s revelations: ‘blushes would suffuse the cheeks of most husbands if they were forced to relate those anecdotes of their wives which Mr Godwin voluntarily proclaims to the world. The extreme eccentricity of Mr Godwin’s sentiments will account for this conduct. Virtue and vice are weighed by him in a balance of his own. He neither looks to marriage with respect, nor to suicide with horror.’

The Anti-Jacobin Review delivered a general onslaught on the immorality of everything that Wollstonecraft was supposed to stand for: outrageous sexual behaviour, inappropriate education for young women, disrespect for parental authority, non-payment of creditors, suicidal emotionalism, repulsive rationalism, consorting with the enemy in time of war, and disbelief in God. It implied that the case was even worse than Godwin made out, and that Mary was generally promiscuous – ‘the biographer does not mention her many amours’. Finally it provided a helpful index entry to the more offensive subject-matter of the Memoirs:

Godwin edits the Posthumous Works of his wife – inculcates the promiscuous intercourse of the sexes – reprobates marriage – considers Mary Godwin a model for female imitation – certifies his wife’s constitution to have been amorous – Memoirs of her – account of his wife’s adventures as a kept mistress – celebrates her happiness while the concubine of Imlay – informs the public that she was concubine to himself before she was his wife – her passions inflamed by celibacy – falls in love with a married man [Fuseli] – on the breaking out of the war betakes herself to our enemies – intimate with the French leaders under Robespierre – with Thomas Paine …

James Gillray, quick to sense a public mood, produced one of his most savage cartoons in the Anti-Jacobin for August 1798. Mockingly entitled ‘The New Morality’, it showed a giant Cornucopia of Ignorance vomiting a stream of books into the gutter: they include Paine’s Rights of Man, Wollstonecraft’s Wrongs of Women, and Godwin’s Memoirs. Godwin looks on in the guise of a jackass, standing on his hind legs and braying from a copy of Political justice.

The Gothic novelist Horace Walpole described Wollstonecraft as ‘a Hyena in petticoats’. The polemicist and antiquarian Richard Polwhele leapt into print with a lengthy poem against her, entitled ‘The Unsexed Females’ (1798):

See Wollstonecraft, whom no decorum checks,

Arise, the intrepid champion of her sex;

O’er humbled man assert the sovereign claim,

And slight the timid blush of virgin fame …

The Reverend Polwhele goes on piously to enumerate her love affairs, her illegitimate child, her suicide attempts, and her lack of religion. Furthermore, he accuses Wollstonecraft of leading astray a whole generation of ‘bluestockings’ and female intellectuals. They are ‘unsex’d’ (presumably like Lady Macbeth), in the sense of having abandoned their traditional role as wives and mothers. They are a ‘melting tribe’ of vengeful, voracious and intellectually perverted women authors who have been seduced by Wollstonecraft’s principles.

Polwhele cites them by name, in what is intended as a litany of shame and subversion: among them Mary Hays, Mrs Barbauld, Mary Robinson, Charlotte Smith and Helen Maria Williams. This was also, perhaps more sinisterly, intended as a kind of blacklist of politically suspect authors, whose books no respectable woman should purchase. Many of these were of course friends of Godwin’s, and they do indeed represent an entire generation of ‘English Jacobin’ writers, for whom the American and French Revolutions had been an inspiration, and against whom the tide of history was now ineluctably turning. For many of them the paths of their professional careers would henceforth curve downwards towards poverty, exile, obscurity and premature death.

It was now open season on Godwin. Yet paradoxically the Memoirs were selling briskly, for a second edition was called for by the summer of 1798. There were also printings in France and America. After anxious discussion with Joseph Johnson, Godwin made a series of alterations in the text, most notably rewriting (or rather, expanding) passages connected with Henry Fuseli, Mary’s suicide attempt in the Thames, and the summary of her character with which the biography concludes.

He also suppressed the references to the Wedgwood family, and rephrased sentences that had been gleefully taken by reviewers as sexually ambiguous. But the overall character of the Memoirs was unchanged, and it remained an intense provocation. Other events also served fortuitously to keep up the sense of a continuing outrage against public morals. One of Mary’s ex-pupils from the Kingsborough family was involved in an elopement (and murder) scandal, while Johnson himself was imprisoned for six months for publishing a seditious libel, though one quite unconnected with the Memoirs. The sentence broke the elderly Johnson’s health, and effectively ended his career as the greatest radical publisher of the day.

The Anti-Jacobin and other conservative magazines felt free to keep up their attacks for months, and indeed years, descending to increasing scurrility and causing Godwin endless private anguish. Three years later, in August 1801, the subject was still topical enough for the young Tory George Canning to publish a long set of jeering satirical verses, entitled ‘The Vision of Liberty’. It was not even necessary for Canning to give Godwin and Wollstonecraft’s surnames. One stanza will suffice:

William hath penn’d a wagon-load of stuff

And Mary’s Life at last he needs must write,

Thinking her whoredoms were not known enough

Till fairly printed off in black and white.

With wond’rous glee and pride, this simple wight

Her brothel feats of wantonness sets down;

Being her spouse, he tells, with huge delight

How oft she cuckolded the silly clown,

And lent, o lovely piece! herself to half the town.

Wollstonecraft’s name was now too controversial, or even ridiculous, to mention in serious publications. Her erstwhile supporter Mary Hays omitted her from the five-volume Dictionary of Female Biography that she compiled in 1803. The same astonishing omission occurs in Mathilda Bentham’s Dictionary of Celebrated Women of 1804. Satirical attacks on Godwin and Wollstonecraft continued throughout the next decade, though many were now in the form of fiction.

Maria Edgeworth wrote a satirical version of the Wollstonecraft type in the person of the headstrong Harriet Freke, who appears in her novel Belinda (1801): she promulgates casual adultery, smart intellectual repartee and female duelling. The beautiful and once-flirtatious Amelia Alderson, now safely married to the painter John Opie (who had executed the tender portrait of Wollstonecraft that hung in Godwin’s study), reverted to the most traditional values of secure and happy domesticity. Using Wollstonecraft’s story, she produced a fictional account of a disastrous saga of infidelity and unmarried love in Adeline Mowbray (1804). Much later Fanny Burney explored the emotional contradictions of Wollstonecraft’s life in the long debates on matrimony and love which are played out like elegant tennis rallies (more raquette) between the sensible Juliet and the passionate Elinor in The Wanderer; or Female Difficulties (1814).

Alexander Chalmers summed up the case against Wollstonecraft in his entry for The General Biographical Dictionary, which appeared in 1814, at the very end of the Napoleonic Wars. This was a time when patriotic feeling was at its height, and distrust of subversive or vaguely French ideologies at its most extreme. Mary Wollstonecraft was accordingly dismissed as ‘a voluptuary and a sensualist’. Her views on women’s rights and education were stigmatised as irrelevant fantasies: ‘she unfolded many a wild theory on the duties and character of her sex’. Her whole life, as described by Godwin, was a disgusting tale, and best forgotten: ‘She rioted in sentiments alike repugnant to religion, sense and decency.’ It is perhaps no coincidence that less than two years later Jane Austen’s Emma (1815) was published to great acclaim. A new kind of heroine was being prepared for the Victorian age.

4

From this time on Mary Wollstonecraft’s name remained eclipsed in Great Britain for the rest of the nineteenth century. There was only one further Victorian reprinting of The Rights of Woman until its centenary in 1892; and no further editions of the Memoirs until 1927. Respectable opinion was summed up by the formidable Harriet Martineau in her Autobiography, written in 1855 and published in 1870: ‘Women of the Wollstonecraft order … do infinite mischief, and for my part, I do not wish to have anything to do with them.’ She concluded that the story of Mary’s life proved that Wollstonecraft was neither ‘a safe example, nor a successful champion of Woman and her Rights’.

The force and endurance of these attacks, and the sense of shock and outrage that they express, suggest that the Memoirs had touched a deep nerve in British society. The book had arrived at a critical moment at the end of the 1790s, when both political ideology and social fashion had turned decisively against the revolutionary hopes and freedoms that Wollstonecraft’s life represented. It was a time of political reaction and social retrenchment. It was also wartime.

As William Hazlitt later wrote of Godwin: ‘The Spirit of the Age was never more fully shown than in the treatment of this writer – its love of paradox and change, its dastard submission to prejudice and the fashion of the day … Fatal reverse! Is truth then so variable? Is it one thing at twenty and another at forty? Is it at a burning heat in 1793, and below zero in 1814?’

It is now possible to see a little more clearly what made the Memoirs so provocative and so remarkable. No one had written about a woman like this before, except perhaps Daniel Defoe in the fictional Lives of his incorrigible eighteenth-century heroines, like Moll Flanders or Roxana. But Godwin was writing strict and indeed meticulous non-fiction, using a plain narrative style and a fearless psychological acuity. He signally ignored, or even deliberately aimed to provoke, proprieties of every kind, especially political and sexual ones.

Beginning with her uncertain birth in 1759 (Mary was unsure whether she was born in Spitalfields or Epping Forest), Godwin unflinchingly describes her restless and unhappy childhood, dominated by a drunken, bullying and abusive father and a spoilt elder brother. His account gives the famous and iconic picture of Mary sleeping all night on the floor outside the parental bedroom, hoping to protect her mother from her father’s assaults. This upbringing left her the victim of lifelong depressive episodes, alternating with periods of reckless energy and anger: ‘Mary was a very good hater.’ But she was determined on a lifelong project of ‘personal independence’, and revealed an instinctive desire to control and manage those around her.

He next recounts her overwhelming and ‘fervent’ friendship for the beautiful Fanny Blood, ‘which for years constituted the ruling passion of her mind’. Godwin has no reservations in proclaiming how deeply those feelings shaped Mary’s emotional life in her twenties, and it is here that he first makes the notorious comparison between her and Goethe’s lovelorn young Werther. The friendship took Mary on her first remarkable voyage, to Portugal in 1785, where Fanny died in childbirth. This passionate attachment was never subsequently forgotten.

The atheist Godwin also sympathetically describes and analyses Mary’s religious beliefs. He treats them in a strikingly modern and psychological way, less as the product of Christian dogma or ‘polemical discussion’, and more as an imaginative expression of her temperament and character: ‘She found inexpressible delight in the beauties of nature, and in the splendid reveries of the imagination … When she walked amidst the wonders of nature, she was accustomed to converse with her God.’

Next comes her combative experiences as a governess in Ireland, and the discovery of her charismatic talents as a teacher, and gifts as an educational writer. This is followed from 1788 by the excitement of her early freelance work in London, and her professional friendship with the publisher Joseph Johnson, during which an intense period of self-education takes place. At the same time she takes responsibility for the careers and financing of most of her family, including her sisters and her father.

Then in 1792, at the age of thirty-three, and at a climactic moment in revolutionary history, she achieves the rapid and triumphant writing of The Rights of Woman, in which she brings both her wide reading and her bitter personal experiences to bear, and makes herself, in Godwin’s words, ‘the effectual champion’ of her sex. Yet in the very midst of this long-dreamt-of literary success, she is frustrated and humiliated by her ill-judged affair with the married (but bi-sexual) painter Henry Fuseli, whose exact nature Godwin leaves for once unexpectedly ambiguous and ill-defined.

It is exactly at this crucial halfway point in his narrative, and significantly just out of chronological sequence, that Godwin ironically places his own first and deeply unsatisfactory meeting with Mary, at the dinner party with Johnson and Tom Paine in November 1791. Far from being love at first sight, they quarrel so fiercely that Paine hardly gets a word in edgeways. It is typical of Godwin that he does not omit this memorable scene, and it remains an exemplary demonstration of both his honesty and his modesty.

From now on the biography seems to accelerate and intensify. Mary sets out on her own to observe events in revolutionary Paris, and as the Terror begins, falls in love with the handsome American adventurer Gilbert Imlay. Godwin’s description of her sexual awakening by Imlay, using the beautiful pre-Freudian imagery of ‘a serpent on a rock’, is another of his triumphs as a biographer, and one wonders how much it must have cost him. Here the comparison with the suicidal young Werther is also repeated.

Mary is registered as Imlay’s wife, and in 1794 bears his illegitimate child – named Fanny (after Fanny Blood) – in Le Havre-Marat. She embarks on a desperate journey to Scandinavia, transforming a secret business venture for Imlay into a captivating Romantic travelogue, sharpened with brisk passages of social comment (about contemporary attitudes to women, education and domestic work), contrasted with moments of intense loneliness and deep self-questioning. Godwin’s emotional account of his personal reaction to this work prepares the ground for the unexpected love match that will follow:

If ever there was a book calculated to make a man in love with its author, this appears to me to be the book. She speaks of her sorrows, in a way that fills us with melancholy, and dissolves us in tenderness, at the same time that she displays a genius which commands our full attention.

On Mary’s return to London in 1795 she discovers that she has been abandoned and betrayed by Imlay, and twice tries to commit suicide, first with an overdose of opium, and then by jumping into the Thames. Godwin’s vivid and moving account of this second attempt includes another unforgettable image: that of Mary all alone at night in the pouring rain, pacing back and forth on Putney Bridge, hoping that by soaking her clothes she will drown more quickly when she summons the courage to leap from the parapet. Paradoxically, it opened Godwin to the charge of trying to make a moral defence of suicide.

The remaining two chapters become increasingly confessional. Yet they are written in the same admirably limpid and economic style, in which tight understatement is deliberately used to contain overwhelming emotion. Godwin describes how they fell in love in the spring of 1796, and began sleeping together in August, long before their mutual decision to marry – which was only taken after Mary became pregnant. Such a candid admission opened Godwin to further mockery and abuse, although he refused to alter it in the second edition.

Finally, at great length and in almost gynaecological detail, without the least reference to the traditional comforts of religion, Godwin painfully and minutely describes Mary’s death, eleven days after bearing her second child. It was the first time a deathbed had been described in this intimate way, including such unsettling details as Mary being given puppies to draw off her breast-milk, and being dosed with too much wine in a vain attempt to dull her pain.

5

Some two centuries later it is still possible to find the Memoirs shocking, and to question the picture it draws of Wollstonecraft. Many feminist critics believe that it miscasts her as a Romantic heroine, and fatally undervalues her intellectual powers. Most of her modern biographers freely use Godwin as wonderful source material, but condemn him as a hopelessly biased witness.

Even an outstandingly perceptive and measured writer like Claire Tomalin is uneasy about the effect of his work. She writes in her early, groundbreaking biography of 1974, The Life and Death of Mary Wollstonecraft: ‘In their own way, even the Memoirs had diminished and distorted Mary’s real importance: by minimising her claim to be taken seriously for her ideas, and presenting her instead as a female Werther, a romantic and tragic heroine, he may have been giving the truth as he wanted to see it, but was very far from serving the cause she had believed in. He made no attempt to discuss her intellectual development, and he was unwilling to consider the validity of her feminist ideas in any detail.’

This has weight, and is curiously close to the criticism originally made by the Analytical Review in 1798. But it has to be set against Godwin’s extended analysis and celebration of the significance of The Rights of Woman in his Chapter 6: ‘Never did any author enter into a cause, with more ardent desire to be found, not a flourishing and empty declaimer, but an effectual champion … When we consider the importance of its doctrines, and the eminence of genius it displays, it seems not very improbable that [her book] will be read as long as the English language endures …’

Much criticism has also been directed against Godwin’s attempt, at the very end of his biography, to summarise Mary’s ‘intellectual character’, and apparently to draw a ‘gendered’ distinction between masculine and feminine intelligence. He contrasts his own cool, rational delight in ‘logic and metaphysical distinction’ with her strong, warm emotional instincts and ‘taste for the picturesque’. This is easily ridiculed. But it is overlooked that Godwin, the faithful biographer, was actually paraphrasing one of Wollstonecraft’s own letters to him of August 1796. This is what Mary herself wrote on the subject:

Our imaginations have been rather differently employed – I am more a painter than you – I like to tell the truth, my taste for the picturesque has been more cultivated … My affections have been more exercised than yours, I believe, and my senses are quick, without the aid of fancy – yet tenderness always prevails, which inclines me to be angry with myself when I do not animate and please those I love.

The problem of the intimate biography which seems to violate certain codes of family loyalty and trust is still with us, though the boundaries shift continually. Over forty years ago, it was Nigel Nicolson’s Portrait of a Marriage (1973), revealing his mother Vita Sackville-West’s lesbian relationships, and his father’s homosexual ones, which raised such questions, though it might not do so now. Some twenty-five years later, John Bayley’s account of his wife Iris Murdoch’s relentless destruction by Alzheimer’s disease, in Iris (1998), left many readers and reviewers deeply troubled. Yet both of these are fine books, and it seems likely that biography as a form is destined continually to challenge conventions of silence and ignorance. Moreover, recent developments in the intimate family memoir, such as Rachel’s Cusk’s Aftermath: On Marriage and Separation (2012), or the growing number of confessional blogs on the internet (including the experience of terminal illness or gender transfer), suggest that the very notion of what is biographically private, or ultimately confidential, has profoundly altered, and will continue to do so.

One also has to consider the historical effect of such a powerful biography in a more oblique way. The fact, for example, that Mary Wollstonecraft’s life inspired so many Romantic novels suggests Godwin had also made her something of a legendary figure. The emotional intensity of Marianne Dashwood in Sense and Sensibility, the novel which Jane Austen originally drafted at just this time (1797–98), might owe more than has been suspected to Mary’s flamboyant example.

The outrageous or confrontational element implicit in her personality still contained heroic or exemplary possibilities. Harriet Freke might yet be reincarnated as J.S. Mill’s feminist companion Harriet Taylor, who was largely responsible for Mill’s great work The Subjection of Women (1869). Wollstonecraft was championed by the reformer Robert Owen, and written about admiringly in a little-known essay by George Eliot, comparing her with the American Margaret Fuller, published in 1855 in the pages of the Leader magazine. In 1885 Wollstonecraft was one of the first figures to be included in the ‘Famous Women’ series, published in London and Boston by the Walter Scott Publishing Company, alongside lives of Elizabeth Fry and Mary Lamb. So there is an alternative tradition in which Mary Wollstonecraft’s reputation runs underground through the nineteenth century. It has been traced in a classic of feminist scholarship by Clarissa Campbell, Wollstonecraft’s Daughters (1996).

The underground tradition eventually resurfaces in the superb essay on Wollstonecraft by Virginia Woolf of 1932. Inspired by the tone of the Memoirs, she describes Gilbert Imlay not as a villain but as a callous fool: ‘tickling for minnows he hooked a dolphin’. She celebrates Mary’s relationship with Godwin as the ‘most fruitful experiment’ of her life. Their marriage was ‘an experiment, as Mary’s life had been an experiment from the start, an attempt to make human conventions conform more closely to human needs’. In a striking and prophetic conclusion, Woolf sees the story and example of Mary’s tempestuous life blossoming again among her own contemporaries: ‘She is alive and active, she argues and experiments, we hear her voice and trace her influence even now among the living.’

6

Perhaps it was there from the beginning. A year after the publication of the Memoirs, the poet and novelist Mary Robinson released her Letter to the Women of England, on the Injustice of Mental Subordination (1799). Originally a Shakespearean actress (known as ‘Perdita’ Robinson for her renowned performance in The Winter’s Tale, which famously seduced the teenage Prince of Wales), Robinson later produced literary work in the 1790s that brought her the friendship of both Godwin and Coleridge. Her Letter initially appeared under the pseudonym ‘Anne Randall’, but it was published by Longman, the biggest bookseller in London, and received wide circulation.

Robinson refers openly and admiringly to The Rights of Woman, and salutes Wollstonecraft as ‘an illustrious British female … to whose genius Posterity will render justice’. In a militant footnote she describes herself proudly as ‘avowedly of the same school’ as Mary Wollstonecraft, and prophetically foresees her embattled life as having initiated a long campaign for women’s rights which would stretch far into the nineteenth century: ‘For it requires a legion of Wollstonecrafts to undermine the poisons of prejudice and malevolence.’

One of Mary Robinson’s most striking conclusions at the end of her hundred-page Letter is that Wollstonecraft’s commitment to female education (emphasised by Godwin) led logically to the idea of women going to university: ‘Had fortune enabled me, I would build a UNIVERSITY FOR WOMEN.’ Only then would women truly be equal.

In the year after Wollstonecraft’s death, a new biographical series entitled ‘Public Characters’ (dedicated to the King) was launched, and would continue for the next decade. It carried some thirty ‘living biographies’ per annual issue, and featured such figures as Nelson, Wilberforce, Humphry Davy, Sheridan and Castlereagh. Its second volume (1799) included a twenty-page contemporary biography of William Godwin. It was warmly favourable, and gave a sympathetic four-page account of his marriage to Mary Wollstonecraft (‘that most celebrated and most injured woman’), and unstinting praise for both editions of the Memoirs. It concluded with a remarkable passage that has never been reprinted since:

It was in January 1798 that Mr. Godwin published his Memoirs of the Life of Mrs. Godwin. In May of the same year a second edition of that work appeared. A painful choice seems to present itself to every ingenuous person who composes Memoirs of himself or of any one so nearly connected with himself as in the present instance. He must either express himself with disadvantage to the illiberal and malicious temper that exists in the world, or violate the honour and integrity of his feelings.

Yet that the heart should be known in all its windings, is an object of infinite importance to him who would benefit the human race. Mr. Godwin did not prefer a cowardly silence, nor treachery to the public, having chosen to write. Perhaps such works as the Memoirs of Mrs. Godwin’s Life, and Rousseau’s Confessions, will ever disgrace their writers with the meaner spirits of the world. But then it is to be remembered, that this herd neither confers, nor can take away, fame.

Most moving of all, the revolutionary influence of Mary Wollstonecraft’s life continued through the next generation of her own family, the family she never knew. It was a powerful and unsettling example. Her love child, Fanny Imlay, eventually committed suicide. But when her daughter Mary Godwin and Shelley eloped to France in 1814, they carried the Posthumous Works and the Memoirs with them in their tiny travelling trunk, and read them during their first nights in Paris. Shelley’s poem The Revolt of Islam (1818) contained a heroic portrait of Wollstonecraft. The triumphant chorus from his late verse drama Hellas (1821), written about the Greek War of Independence, drew on Godwin’s memorable snake imagery of hope and revival:

The world’s great age begins anew,

The golden years return,

The earth does like a snake renew

Her winter weeds outworn …

Mary Shelley’s entire literary career was inspired by her mother’s example, and especially perhaps her desire to write novels of ideas. Both Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus (1818) and The Last Man (1826) can be seen as part of the complex Wollstonecraft inheritance. After her father William Godwin’s death, she always intended to write a combined biography of both her daring literary parents. A few scattered manuscript notes alone have survived, probably dating from the early 1840s. Here is what the subdued, widowed, middle-aged Victorian Mary Shelley wrote about her outrageous mother Mary Wollstonecraft:

Her genius was undeniable. She had been bred in the hard school of adversity, and having experienced the sorrows entailed on the poor and oppressed, an earnest desire was kindled within her to diminish these sorrows. Her sound understanding, her intrepidity, her sensibility and eager sympathy, stamped all her writings with force and truth, and endorsed them with a tender charm that enchants while it enlightens. She was one whom all loved, who had ever seen her.

But of course Mary had never seen her mother. She only knew and loved her through her own writings and her father’s intrepid and controversial Memoirs. Such is the dangerous, enduring power of biography.