Above: Dawn ferry across Sierra Leone River estuary approaching Freetown, January 2009

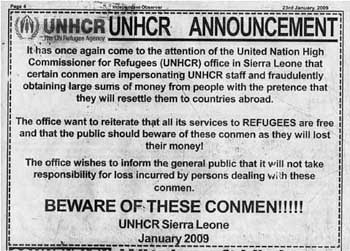

Below: Sierra Leone newspaper advert warning about fraudulent asylum providers

The bass blast from the ferry’s horn bounced back from the sea fog making my chest shudder, but the other passengers on the open deck atop the MV Great Scarcies carried on their early-morning chatter without interruption. Listening to them was like tuning a short-wave radio, the babble of foreign sounds every so often crystallising into a familiar word. They were speaking Krio, the broken form of English with roots reaching back to eighteenth-century mariners and which is still the main language of Sierra Leone. I heard tok for talk, aks for ask and pekin for child – derived from piccaninny.

As the ferry slipped away from the quayside of the Tagrin terminal on the north shore of the Sierra Leone River, I could barely feel the swell of the nearby Atlantic. The river estuary provides Africa’s greatest natural harbour, a freak combination of powerful tidal currents that prevent silting in a deep channel tucked behind a mountainous peninsula acting as a bulwark against the ocean’s motion. When Sierra Leone’s capital, Freetown, was founded it was natural that the city should be built on the estuary’s southern shore, the sheltered, inland side of the forested peninsula with its plentiful supply of fresh water from mountain streams.

Leaving the dock I watched a vulture circle slow and high above Tagrin just as everything beyond the confines of the ferry was swallowed by the mist. An evangelist stood up from among the packed benches, held a Bible aloft and began to praise the Lord. He wore opaque sunglasses and as his rhetoric built his head bobbed with the slightly unnatural articulation of the unsighted.

On the car-deck every inch between the vehicles was taken up by passengers, mostly women hawkers with cotton lappa wraps pulled tight around their shoulders for warmth. At their feet were baskets heaped with produce: cairns of bananas, peanuts bundled by the handful in knotted twists of plastic, portions of fried yellow plantain freckled with tiny black seeds and tinged red by the palm oil they had been cooked in. Young men sat astride motorbikes, cheap Chinese-made models with the excess of chrome common to second-rate machinery.

We were still close enough to the shoreline for the air to have the distinctive smell of Sierra Leone, a warm fragrance just on the pleasant compost side of rotting. I had smelled it first on my chaotic arrival here in 2000 and nine years later I had smelled it again when I flew into a much more peaceful Lungi international airport the evening before boarding the ferry. The old baggage hall, where British troops had once set up bivouacs next to the luggage carousel, had been newly painted, the walls plastered with adverts for expensive beachfront properties. One of the smartest developments offered ‘boys’ quarters’. It showed how little had changed for the wealthy elite of Sierra Leone since the Greenes arrived in Freetown in January 1935 for the start of their journey and went in search of servants they also referred to as ‘boys’.

The topography that had blessed Freetown in the era of sail now cursed it in the era of flight, hobbling the city’s development. The main airport had been built at Lungi on the flatter, northern side of the estuary, meaning that people arriving by air face a fiddly onward journey to reach the city on the southern shore. To go overland involves a drive along second-rate roads ballooning far inland to get round the vast river mouth, a journey that can easily take ten hours in the rainy season. In peacetime, Tagrin ferry terminal offers a cheap but slow option preferred by most locals – although wealthier travellers have in recent years been able to choose from speedboats, helicopters and even hovercraft, all of which are costly and sometimes spectacularly unreliable. British diplomats were recently banned from using the helicopter service after one of the aircraft burst into flames in mid-air killing all on board. The diplomats responded by buying their own motorboat for airport connections, complete with tiny flagstaff from which the High Commission’s official standard flies in miniature.

The ferry had not been running during the war and I rather relished this chance to reach one of the world’s great seaboard cities by boat. Like many planes, ships, vehicles and other pieces of mechanical equipment in Africa, the Great Scarcies arrived here very much second-hand. Laxer safety standards mean machinery often comes to Africa in its dotage and airfields and ports all around the continent are full of venerable vehicles eking out the twilight of functionality. The Great Scarcies used to run European holiday-makers between the Greek islands in the 1980s and 1990s before a consortium of Sierra Leonean businessmen spotted a post-war opportunity and arranged for her to venture round the top left corner of Africa before creeping south along the edge of the Atlantic all the way to Freetown.

‘She’s a good enough ship,’ Tholley Ahmed, the bosun, told me as he stared into the offing after we got underway. The bridge had no radar so during the hour-long crossing, the skipper relied heavily on Tholley’s eyesight. When I asked about the owners, Tholley glanced round at me and replied with a somewhat resigned tone, ‘They’re Lebanese.’

It is a quirk of West Africa that a small but powerful community of immigrants from the Levant has made it their home since the 1920s, accepting the very real risks of occasional war and unrest in exchange for access to lucrative local business. Graham Greene chose a manipulative Arab diamond smuggler as the villain of his Sierra Leone-based novel The Heart of the Matter, written in the late 1940s, and on my earlier visits to Freetown I learned the local Lebanese business community was stronger than any other. My work as a journalist has often taken me to Beirut where the long-serving Shia speaker of parliament, Nabih Berri, one of the key players in the muddled mosaic of modern Lebanese politics, speaks proudly of having been born in Sierra Leone.

The passengers continued to chat as Tholley scanned a horizon growing as the rising sun gathered in the mist. A local fishing boat powered by an outboard engine came into view, its low, painted wooden flanks rising to an elegant prow with a single upright figure, muffled up against the chill, at the sternpost, hand on the tiller. Known in these waters as banana boats, they pay scant attention to international frontiers, slipping up and down the coast from Sierra Leone as far round as Nigeria, more than a thousand miles to the east. I could see a white flag on a bamboo cane sticking from the prow. Coastal fishermen were among the first Africans to receive the attention of Christian missionaries and I was sure the flag carried a biblical invocation seeking protection from the perils of the sea.

Down on the car-deck there was movement. The motorbikers had begun fidgeting with their kick-start pedals and the women were standing, stretching out of their lappa cocoons. Those who had heavy loads to carry on their heads fashioned hand cloths into quoits to cushion their scalps. I looked far ahead and could see why they had stirred. Freetown was coming into view.

At first it was like a watery Japanese print as I could make out only the blurred loom of mountain ranges overlaid more and more faintly, one behind the other. But as the mist dissolved the focus sharpened to reveal under the hills a shoreline of buildings, rooftops, tower blocks and the occasional startled outline of a leafless cotton tree. The sight reminded me of Graham Greene’s description of Freetown as ‘an impression of heat and damp’. But it also made me think of the first European explorer to describe the area in writing, a Portuguese mariner called Pedro da Sintra, who arrived around 1462 and wrote of a ‘high mountain summit which is continually enveloped in mist’.

Da Sintra must have come here during the rainy season, as he described how thunder could be heard coming perpetually from the cloud-bound massif. He called it Serra Lyoa, which can be translated as the ‘Mountain of the Lioness’. As this part of Africa has always been too forested to have supported its own lion population, it is thought he meant either that the constant roaring sounded like a lion or that, to his eye, the mountain was shaped like a lion. Historians remain divided on the issue but they agree that within a hundred years or so his Serra Lyoa spelling had morphed into Sierra Leone.

The discovery of a sheltered harbour with a plentiful supply of drinking water on the otherwise hostile low-lying, disease-ridden coast of West Africa meant that by the sixteenth century Sierra Leone was already receiving plenty of visitors by ship. There were traders, initially Portuguese, and their footprint is still evident today. A white person walking into a rural village near the coast of Sierra Leone will hear the children crying out ‘Oporto, Oporto’, the favoured local term for white man. Later came the Dutch and then the British, some of whom stayed in the area, often on off-shore islands chosen for protection. Several began families with the local population and opened trading posts. Archaeology, linguistics and oral tradition indicate various African forest-dwelling tribes had lived in the area for hundreds of years before da Sintra arrived and it was with these long-standing tribes like the Sherbro, Bullom and Temne that trade began. It started conventionally enough with the exchange of European manufactured goods for African craftwork, but the discovery of the New World at the end of the fifteenth century and the subsequent demand for slaves to work on plantations in the Americas changed everything.

Suddenly the Sierra Leone River estuary saw the arrival of more ruthless traders, interested only in profitable human plunder. There were raiders like Sir John Hawkins, the Elizabethan sailor whose hugely profitable first slaving expedition took him in 1562 from England via Sierra Leone to the Caribbean, and later, Bartholomew Roberts, a drunken, ruthless Welshman who captured more ships than any other buccaneer during the golden age of piracy and came to Sierra Leone in the early eighteenth century to burn the official British slaving fortress to the ground. The dominant Temne chiefs showed no scruples in selling prisoners from their regular inter-tribal wars to white outsiders and soon the estuary had become a nest of pirates and slavers, earning the following colourful description in the classic work, A General History of the Pyrates, published in the 1720s:

There are about 30 English men in all, Men who in some Part of their Lives, have been either privateering, bucaneering or pyrating, and still retain and love the Riots and Humours, common to that sort of life. They live very friendly with the Natives, and have many of them … to be their Servants; The Men are faithful, and the Women so obedient, that they are very ready to prostitute themselves to whomsoever their Masters shall command them.

The dissolute character of the region in the late eighteenth century makes the next chapter in its history quite extraordinary. In London a group of high-minded idealists, supported, it must be admitted, by opportunists and even a few racists, settled on Sierra Leone as the site for a pioneering experiment in social engineering. The streets of Britain’s growing cities were then crowded with the poor, among whom a few thousand non-white faces stood out. Some were slaves brought from the Americas to Britain by plantation owners and then freed; others were lascars, sailors who had joined British crews in the East Indies and disembarked in the port of London; others were former slaves who had fought with the British on the losing side in the American War of Independence and then fled to London, fearing they would once again be enslaved if they stayed in America.

They might have had a wide range of backgrounds but with few exceptions they lived the same wretched life of penury, begging on the streets of London and Britain’s other major ports. This was the era of salon politics, when hugely important decisions could be made by small groups of the great and the good meeting not in parliament or government buildings but in private houses or bars. Such a gathering created the Committee for the Relief of Black Poor in January 1786. Its original aim was to collect money and rations for destitute blacks in Britain but within a few months the committee’s all-white members, meeting originally in the Bond Street home of a wealthy bookseller but later at Batson’s, a coffee shop in the City of London, came up with a far more ambitious plan.

The committee would persuade poor blacks to leave Britain and go to the tropics to found a utopian community where they could eventually rule themselves, free of the control of white superiors. The abolition of slavery was then being debated by Britain’s ruling elite and the idea of giving the black poor their own colony was supported keenly by some of Britain’s leading abolitionists. But it also received the backing of some of Britain’s most high-profile supporters of slavery, owners of sugar plantations in the West Indies, who embraced the idea of clearing London of its black poor and thereby getting rid of a potentially troublesome reservoir of hostility to slavery.

Various places were suggested as a suitable location for the experiment, including the Bahamas, but, after discussion with representatives of London’s black community, Sierra Leone was chosen as the site for what was originally to be called the Land of Freedom, changed later to the Province of Freedom. In copperplate manuscript, a minute dated Wednesday 26 July 1786 recorded what was discussed by committee members meeting at Batson’s Coffeehouse.

Five of the Deputies of the Blacks … mentioned a Person now living in London who is a native of that country [Sierra Leone] and gives them assurance that all the natives are fond of the English & would receive them joyfully.

The brains behind the Sierra Leone plan was an English amateur botanist and abolitionist named Henry Smeathman, who had come to know the Sierra Leone River estuary in the early 1770s through several years spent on a nearby island studying plants and developing a fixation with termites. This was a time when most of the whites based in the area were involved in slavery but while Smeathman opposed the trade he appears a cheerful fellow, not interested in making an issue out of his hosts’ occupation. When in 1773 he visited Bunce Island, site of the main British slaving fortress within the Sierra Leone River estuary, his diary recorded rather pleasant games of golf. It was only a few years since golfers in Scotland had come together to form what would later become the Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St Andrews but Smeathman describes in detail how the slavers of Bunce Island passed the time in between slaving raids by playing a game he called goff.

We amused ourselves for an hour or two in the cool of the afternoon in playing at Goff, a game only played in some particular parts of Scotland and at Blackheath. Two holes are made in the ground at about a quarter of a mile distance, and of the size of a man’s hat crown … That party which gets their ball struck into the hole with the fewest strokes wins.

Smeathman was approached by the committee because of his experience of living in West Africa and, notwithstanding the presence of various slaving sites in and around the Sierra Leone River estuary, he was able to convince the committee the area would make a perfect site for the relocation of Britain’s black population. He died before the first ships set sail.

The relocation plan was high-minded and not a little confused. It referred to ‘Asiatic blacks’, the lascars, as being suitable for resettlement in Africa even though they came from the Far East. It bundled them together with black people whose roots did at least reach back to Africa but to parts of the continent hundreds, sometimes thousands of miles away from Sierra Leone. And for good measure the committee included more than sixty white women in the settlement plan, prostitutes in the eyes of some historians, lawful partners of poor blacks in the eyes of others. The thinking of the white committee members might have been driven by philanthropy but it betrayed a clear conceit, the idea that non-whites and their hangers-on could effectively be dumped in any old part of Africa.

There was little joy in the reception given to the 411 predominantly black settlers who eventually reached the Sierra Leone River estuary in May 1787 on three Royal Navy ships chartered by the committee behind the Province of Freedom. At first the local Temne chief was happy enough to accommodate the new arrivals. During his life King Tom had seen plenty of foreign outsiders, mostly slavers and brigands, pass through his territory and although the new group was slightly different in that it was made up mostly of black people, he had no qualms about signing a treaty on 11 June 1787 with their white leaders concerning ownership of the mountain peninsula which ended:

And I do hereby bind myself, my Heirs and Successors, to grant the said free Settlers a continuance of a quiet and peaceable possession of the Lands granted their Heirs and Successors for ever.

In exchange for ceding the peninsula in perpetuity, King Tom received a bundle of items valued at a few pennies over £59. It included eight muskets, a barrel of gunpowder, two dozen laced hats, bunches of beads, a length of scarlet cloth and, in a gesture worthy of the region’s piratical history, 130 gallons of rum.

In those early days there were moments of excitement when the pioneers made encouraging discoveries that hinted at a land of plenty. A bushfire one day was followed by the distinctive smell of roasted coffee. On closer inspection, the settlers found part of a hillside thick with wild coffee plants. But various delays and problems en route had meant the settlers arrived in the country at the worst possible time of year, with the rainy season just beginning. No staple crops could survive the ferocious storms, while malaria and other waterborne diseases spiked. Within three months a third of the settlers were dead, their immune systems ravaged by hunger and exhaustion. Several key white officials, including the two doctors and the chaplain, who had been specially commissioned to help set up the Province of Freedom, did not just run away, they betrayed the whole ethos of the project by joining the slavers on Bunce Island. Occasionally some of the black settlers – freed slaves themselves – preferred to move to Bunce Island where they could at least get food, shelter and even wages in exchange for helping with the ongoing shipment of slaves. The dreamers back in London struggled to understand how freed slaves could themselves turn into slavers.

The first Province of Freedom effectively ended in 1789 with confusion and betrayal when, after a squabble, the settlement was burned to the ground by King Jimmy, King Tom’s successor, forcing the few remaining settlers to flee into the bush. But the committee back in London refused to give up, sending out a colonial agent who found only sixty-four survivors from the original 411, among them a few hardy white women described unfavourably by one observer as ‘strumpets’. It was just enough to found a new settlement in an abandoned Temne village consisting of seventeen mud huts. According to local lore, the houses had been abandoned because they had been ‘occupied by devils’ but this did not seem to deter the agent.

What the project needed most was people, so the philanthropists sent out another tranche of black settlers in 1792, this time drawn not from the streets of London but from Nova Scotia, the rocky promontory off North America where large numbers of former black slaves from America had ended up after fighting with Britain when America won its independence. They had been forced to flee America when Britain surrendered but, instead of enjoying full freedom under the British authorities in Nova Scotia, they endured a wretched existence struggling against the bitter winters, poor soil and colonial laws that left them, in some ways, worse off than they had been as slaves. Around a thousand were happy to leave the icy, rocky shore of Nova Scotia and sail to Sierra Leone, where they gave the name Freetown to the settlement they founded. And a few years later the Nova Scotians were followed by another group of settlers, Maroons, who were slaves deported from Jamaica after rebelling against their masters.

But the development that really saved the Province of Freedom project was, ironically, something that ensured its black population would never in their lifetimes enjoy proper freedom. In 1808 the mountain peninsula guarding the Sierra Leone River estuary became a full British colony.

The original plan by the eighteenth-century philanthropists had been to create a community where black settlers would be in charge of their own destiny. Quite how they would live alongside the indigenous population was a question not really dealt with by the dreamers, but the point was that blacks would, through the munificence of British philanthropy, be free to rule themselves – a beacon to all those still trapped in slavery around the world.

That dream came to an abrupt end in 1808 when the company set up by the philanthropists to run the Province of Freedom effectively became bankrupt and the British government moved in to stake the peninsula as a colony. This heralded a boom period for black settlement in Sierra Leone as, following the work of abolitionists led by William Wilberforce, the Royal Navy moved to enforce the 1807 ban on the slave trade. Navy ships were deployed along the west coast of Africa with orders to intercept ships carrying slaves across the Atlantic and it was to the newly founded colony of Sierra Leone that these warships would come to off-load the so-called ‘recaptives’, Africans who had been captured once by slavers and again by the Royal Navy. No matter where these people came from they found themselves settled, in ever increasing numbers, in what had been set up as the Province of Freedom.

In 1808 the settler population of Sierra Leone was just 2,000, made up of remnants of the London settlers, the Nova Scotians and Maroons. The recaptives soon swamped this original group, with the Royal Navy delivering a total of 6,000 slaves retaken on the high seas by 1815. The influx continued at a similar pace over the next thirty years, meaning that recaptives became by far the dominant settler community in Freetown.

But the irony was that, in spite of the growing number of black settlers, colonial rule meant a small cohort of white officials, appointed by the British government in London, still ran the affairs of a much larger black population, both settlers and indigenous Africans. It meant the dream of the philanthropists was only ever half fulfilled. Yes, black settlers had been saved from slavery, but they never enjoyed full freedom. And tension between white colonials, black settlers and indigenous people would dominate every subsequent turn in the history of Sierra Leone.

*

Traces of Freetown’s ancestry were visible everywhere as I made my way into the city to prepare for my journey across Sierra Leone and Liberia. After the relative cool of the early-morning crossing, I had stepped off the ferry and felt the true weight of West Africa’s climate. By the time I found a taxi, an old Mercedes estate with a German number plate, I had already begun to flag. Wilting into its saggy front seat, I groped for the window handle but found only a knurled, rusty stub. Taking pity on me, the dreadlocked driver, George Decker, leaned across and slapped the flat of his hand against my window with such force that the glass pane shuddered down.

Traffic oozed like treacle along hot, narrow roads clogged with pedestrians, livestock and hawkers. Street-sellers need not worry about missing a sale as they had plenty of time to catch up with slow-moving vehicles whenever a passenger showed interest in the local newspapers, knock-off DVDs, plastic bags of chilled water or other items for sale. I could barely see through the web of cracks in our windscreen but George kept up a sotto voce commentary on local landmarks, almost all of which were connected to Freetown’s early history.

We inched past Cline Town, one of the larger suburbs, named after Emmanuel Cline, a ‘recaptive’ from Nigeria who made enough money as a trader in the mid-nineteenth century to buy what was then empty land near the shoreline on the eastern approaches to the city. And we paused at what was once Cline Town’s largest building, Fourah Bay College, the oldest university in colonial Africa. Founded in 1827 to train freed slaves as teachers and chaplains, it produced a stream of alumni who took their qualifications far beyond Freetown – the first cohort of modern black professionals to spread across Africa. It earned Freetown the soubriquet of ‘The Athens of Africa’ and a suitably grand three-storey college hall was constructed close to the shoreline. Built out of quarried blocks of laterite, the distinctively coloured pinkish stone that is common on the Freetown peninsula, in its day it would have looked at home in the grounds of any Oxbridge college. Its portico was framed by elegant cast-iron columns, Norman windows lined its flanks and its grounds were tended by a staff of gardeners. But by the time I saw it the elegance was no more. Abandoned when Fourah Bay College moved to other premises, the college building was a roofless ruin, its internal floors concertinaed into a heap of broken masonry and its walls scorched with fires lit by squatters who overran it during the civil war.

George drove through the city centre where the main artery, Siaka Stevens Street, passes under the spreading boughs of the Cotton Tree. Such trees are common across West Africa but this huge specimen in the heart of Freetown commands a special position in the history of the country, protected as a national monument. It was under this tree, in 1792, that a service of thanksgiving was held by the first group of freed slaves arriving from Nova Scotia, as they sought God’s blessing for their new life in Africa. They used it as a centre-point when they laid out Freetown’s original grid of streets leading down a gentle slope to the shoreline of the Sierra Leone River estuary, a grid that remains largely unchanged today. As we drove by I looked up and saw thousands of large bats, each the size of a rat, hanging from its branches in furry, twitching bunches, unmoved by the street noise below.

War and decay meant Freetown was not a city that wore its age well. There were several tired-looking tower blocks in the city centre, many with their own generators noisily providing a private electricity supply for businesses wealthy enough to afford them, separated by streets crowded with hawkers and tatty with rubbish. Statues erected to Sierra Leone’s post-colonial leaders, the ones who guided her through independence in 1961, were in dire need of attention. Noses had fallen off, lettering had faded and ceremonial fountains had dried up. One of Freetown’s oldest buildings, St George’s, the Anglican cathedral built of red laterite which Graham Greene described as dominating the city centre, is now dwarfed by hulking 1960s structures hung with rusting air-conditioner units, paint flaking from the walls.

I later visited the cathedral and found the guest book. It had lost its spine and its pages were grubbily dog-eared, but despite being almost fifty years old it was still not full. The first signature was ‘Elizabeth R’, dated in the Queen’s hand ‘November 26 1961’, and the second was ‘Philip’, the Duke of Edinburgh, marking the royal visit just after independence.

As we continued to drive west we began to pass some of Freetown’s older shingle houses, built in nineteenth-century settler style with walls made of overlapping lengths of roughly hewn timber. The passage of years and ravages of rainy seasons meant the square-cut wooden frames had settled higgledy-piggledy, giving them a naive, pre-modern look, as if they were fairytale houses a child might picture in a magic forest.

In the early years, settlers who were thought by British officials to come from the same parts of Africa were grouped together, setting up their own satellite villages some distance from the town centre and its cotton-tree hub. Slaves from the Congo, almost 2,000 miles south-east of Sierra Leone, set up Congotown, and Yoruba tribesmen from Nigeria set up Aku Town. These names survive today, although the chaotic growth of the city means the communities have long been absorbed into a single, unbroken sprawl.

Originally laid out for a population of a few thousand, the city is now home to more than a million people. As the only large city in Sierra Leone it has traditionally been the main economic magnet for people living up-line, the Krio term for the provinces derived from the days when the railway was the main artery between city and country. When the civil war began in 1991 the city was further inundated, this time by terrified refugees, and although the war officially ended in 2002, Freetown still has the feel of a city overwhelmed. Each year shanties reach higher up the flanks of the mountains behind the city, where once-thick forests have been thinned for firewood to such an extent that in recent years people have been killed by rocks sluiced off the deforested hillsides during the rainy season.

I stayed in the relatively smart suburb of Murraytown with an aid worker friend employed by Oxfam GB, a British charity with a long history of involvement in Sierra Leone. She explained how Murraytown had been chosen for the Oxfam base specifically because the official residence of Sierra Leone’s deputy president was also there, resulting in a greater likelihood of the suburb having mains electricity. That might have been true but during my visit there was not a single day without a power cut.

I saw the deputy president, or, rather, the deputy president’s motorcade, while I was there. Turning on to the road outside our house was a new 4 × 4 jeep with tinted windows, led and followed by military-looking vehicles carrying uniformed men and with blue lights flashing and sirens howling. The convoy did not even slow as it manoeuvred past a large crowd of women and children gathered around a standpipe spewing water onto the road. Murraytown might be one of Freetown’s better areas but, long after the war, its residents still have to queue by the roadside to fetch water by the bucketful.

I had hoped to see significant improvements in Freetown since my first visit. It was seven years since the then president, Ahmed Tejan Kabbah, had famously declared an end to the conflict by announcing in Krio ‘da war don don [the war is finished]’ and in those years hundreds of millions of pounds had been provided in bilateral donations and foreign aid, mostly from Britain. But the truth is that Freetown remains a creaking, crowded, chaotic mess, with families washing in polluted streams in the city centre as basic municipal infrastructure fails to cope. Some modest repair work had been carried out on buildings damaged during the war but in the face of a growing, impoverished population the work seemed like tokenism.

Despite the squalor, it is possible for members of the Sierra Leonean elite – along with NGO workers, diplomats and well-paid expatriates – to live well. These are the people who could realistically consider buying the villas with ‘boys’ quarters’ I had seen advertised back at the airport. But for the vast majority of Sierra Leone’s population this sort of lifestyle is unimaginable. The lack of local production means that shops, still mostly owned by Lebanese immigrants, are stocked with expensively imported goods. Members of the elite retreat with their shopping to houses with high security walls, where the only way to guarantee power is to arrange for your own generator and the only way to ensure regular water is to arrange for your own plastic reservoir tanks. Since 2000 the main cosmetic change I noticed was that the outsides of these large perimeter walls were covered with adverts not for beer or milk powder as before, but for the many local mobile phone companies which had boomed since the war. Instead of printed billboards many of the ads were skilfully hand-painted by locals. Using the template of a page torn from a glossy magazine carrying the advert, the artists would stand in the sunshine meticulously magnifying each image onto the cement walls.

Along many of the main arteries in Freetown I saw clumps of signposts marking the headquarters of aid groups, ranging from the leviathans of the UN, with their multi-billion-pound annual turnovers, to tiny faith-based, private organisations. But there was still scant evidence that the efforts of the aid groups were truly bringing the country on. During my visit a ripple of exasperation passed through the foreign aid community when a survey of all public hospitals in Sierra Leone found only one working X-ray machine serving a country of roughly six million people. And a few weeks later the government had to issue a public statement when survivors of an oil pipeline explosion were taken to Connaught Hospital, one of the largest public health centres in Freetown, only to be told the pharmacy had not a single painkiller or antibiotic.

I got my own sense of Freetown’s developmental problems on my way to meet John, a senior official responsible for some of the best-funded humanitarian programmes in one of the world’s most aid-dependent countries. I could not spot a single new road built in Freetown since the war and yet the number of vehicles had ballooned. I saw new-looking jeeps, owned almost always by aid groups or Lebanese businessmen, but the vast majority of the extra vehicles on the roads were not new at all. They were beaten-up jalopies shipped to Sierra Leone from northern Europe to see out the end of their days as taxis. Many still had white national-identification discs with black letters – B for Belgique, F for France, D for Deutschland – and plenty had ski racks on their roofs, something that even the enterprising cabbies of Freetown had not worked out a use for. Most had had their bodywork customised with painted messages addressing Jesus or Allah depending on the faith of their new owner. ‘Blood of Christ’ was my favourite.

The lack of new roads combined with the surge in car numbers could mean only one thing: traffic-jam hell. Rather than fold myself into a slow-moving, oven-hot poda-poda, I started out on foot for John’s office, turning towards the sea at Congo Cross and walking down past King Tom, a promontory still named for the Temne chief who signed the treaty creating the Province of Freedom more than 200 years ago. The Greenes visited this area when they passed through Freetown in 1935 and Graham Greene was impressed by the simplicity and elegance of the native huts among the palm trees. Seventy years later and those huts had multiplied into a vast shanty town where the normally sweet scent of Sierra Leone was spoiled by foul-smelling smoke from fires lit on a massive open tip and stagnant water in a river so clogged with sewage and rubbish it seemed to have stopped flowing altogether. The only apparent movement in the riverbed came from a large pig, swilling through the stinking gloop.

‘The truth is that in spite of all these years of work Sierra Leone still scores lowest on almost all the major development indicators – infant mortality, maternal death in childbirth, life expectancy. By many standards Sierra Leone is the poorest country on earth, even though it receives so much help. It feels like a stone being rolled along the riverbed, too heavy to ever float upwards,’ John explained over a cup of tea. His office fridge was not working so we used powdered milk.

‘After all the money and all the years, does that depress you?’ I asked. ‘Do those dismal performance indicators not sap your enthusiasm for the job?’

John paused. His headquarters were located high up on one of the Freetown peninsula’s hill ranges with impressive views towards the Atlantic. For a moment he looked out to sea.

‘Strangely, it doesn’t. The greatest achievement of these past few years has been peace. Those indicators tell you nothing about the fact that one of the worst wars in Africa’s history, one the cruellest, one of the nastiest, was brought to an end. Christ, during the war do you think it was even possible to gather meaningful data? There have been two presidential elections since the war ended, peaceful elections that is. And in one of those elections the president not only lost, he handed over power without a single gunshot. You have got to remember that for Sierra Leone that represents huge progress.

‘The achievement of these years has been no war and to the extent that aid programmes have helped with that I think we have every reason to be proud.

‘But the reality is that Sierra Leone is not out of the woods. This place is very, very fragile and the biggest threat comes from a source nobody would have predicted a few years ago – Colombia and its cocaine barons.’

In July 2008 the extent of Sierra Leone’s involvement in international drug smuggling was revealed when a twin-engine Cessna 441 Conquest made an unexpected landing at Lungi airport. The crew asked the tower for permission to land saying they were low on fuel, which was true as they had just flown all the way across the Atlantic from an airstrip in Venezuela close to its border with Colombia. What they failed to mention was that on board they had 703.5 kg of refined cocaine packed in Bible-sized blocks. And what the tower failed to mention in return was that the Sierra Leonean police were on to them. The first the crew knew that something was amiss was when the airport fire tender drove towards them erratically as they taxied. It made the three crew members panic, shutting off the engines, jumping to the ground and trying to escape on foot. They were chased down by policemen while officers hiding on the fire engine secured the plane and its contraband. The Sierra Leone security forces then moved to round up the reception committee, smugglers who had gathered at Lungi waiting for the plane to arrive, and their accomplices on the other side of the estuary in Freetown.

There was a series of chases as jeeps driven by smugglers roared away from the airport but the potholed roads of Sierra Leone are not made for quick getaways and several of the smugglers dumped their vehicles. One bright police officer gave the order that any non-black person found travelling by poda-poda in the north of the country should be arrested and over the next few days all the gang members were picked up.

After a four-month-long trial, one of the longest in Sierra Leone’s criminal justice history, fifteen people were convicted of drugs-related offences. Three of the convicted, American passport-holders, were of sufficient value to the US authorities to be deported to New York to face fresh drug-dealing charges. Back in Freetown, the cocaine, which had been kept as evidence in the trial under the supervision of British soldiers from an army training team, was disposed of by burning in a ceremonial bonfire. The authorities insisted all 703.5 kg went up in smoke.

While the Sierra Leonean authorities can be congratulated for the way in which they dealt with the case, the worry is that other flights might have got through. Only one other cocaine flight is known to have reached Lungi, one that landed in December 2007 before being allowed to continue so that the authorities in Britain could track its onward smuggling route. It is likely there have been other flights the authorities never knew about. There is no real demand for cocaine in Sierra Leone and the smugglers are only interested in the country, along with others in West Africa, as transit points to move their product north into Europe. Their assumption is that weak, corruptible governments in the region can be bought off.

The scale of the threat that drug smuggling poses to Sierra Leone was spelled out in uncharacteristically direct language by Ban Kimoon, the UN Secretary-General, speaking after the plane seizure. He described cocaine trafficking as ‘the biggest single threat to Sierra Leone’.

John added his opinion about the scale of the threat: ‘Don’t forget that the war in Sierra Leone went on for ten years or so, killing tens of thousands of people, largely because rebels could get a hold of a few million dollars from diamonds way out in the east of the country. The sums of money the drug barons can offer are many times bigger and that can buy you a hell of a lot of rebels.’

I headed back to my NGO house with its high security walls, private generator and kitchen where breakfast cereal had to be stored in Tupperware boxes to deter cockroaches. I struggled not to let John’s portentous analysis get me down. I was keen for a more positive vision of Freetown and for that I would have to go and speak to a blind man.

To get to Professor Eldred Jones’s house I did what I had been strongly advised against. I rode pillion on a motorbike taxi. Known as ‘okadas’, they buzz through the catatonic Freetown traffic, providing an effective if hazardous means of transport. My driver came from the fearless school of okada riders, nipping through gaps I never thought he would get through. Several times I closed my eyes, squeezed in my thighs to make our outline as narrow as possible and prayed. I was about to embark on a long trek through the African bush and I would need my kneecaps in working order.

It took some time but I eventually relaxed enough to reopen my eyes. We passed lines of schoolchildren wearing uniforms lifted straight from the 1950s, girls in felt hats and stiffly pleated skirts, boys well into their teens squeezed into short trousers. Quite how their families kept the uniforms so immaculate when living in the derelict shanties of modern Freetown was beyond me. At Congo Cross, a notorious choke point for vehicles, a policeman on traffic duty waved his arms energetically at the stationary traffic. His black beret, blue tunic and creased serge trousers seemed to come straight from the era of National Service in Britain. He looked like an extra in an amateur drama society production.

As the road began to climb a hill the bike slowed, its engine racing against my body weight and the steep incline. Near a bridge over a mountain stream I saw a sign that said nor pis yah. As so often with Krio I had to speak the words out loud before I could work out what they meant. A group of women and children did not seem to be paying the sign much attention as they carried out their ablutions in the watercourse. This stream was close to the catchment of King Jimmy brook, once a source of fresh water so sweet it brought eighteenth-century sailors here from across the seas. The stream still flows today, indeed there is a market named after the King Jimmy stream down on the city waterfront, but today it is a disease-ridden open sewer and the once sandy beach is one great vermin-infested mat of discarded rubbish, rhythmically rucked by the estuary surf.

The road continued to climb, passing abandoned Second World War emplacements where naval guns had once been installed to cover the approaches to Freetown harbour. As a British colony, Sierra Leone had played a modest part in the defeat of Germany. With U-boats menacing re-supply convoys to and from America, allied ships would cling to the African coastline and creep all the way from Britain down to the Sierra Leone River estuary, where the Freetown harbour provided an excellent location to gather convoys in preparation for the trans-Atlantic run. And with the Mediterranean blocked to allied shipping, freighters heading to the Indian Ocean were obliged to take the longer route all the way around Africa, often putting in to Freetown. The harbour got so busy that the older generation from Freetown remember it at times as a solid, grey mass of military shipping.

During the war a military hospital and barracks had been built above the gun emplacement, further up the flank of Mount Aureol, a site chosen deliberately to lift convalescent patients above the ill humours of the city centre. It commanded wonderful views over the estuary and the peninsula, and when the war eventually ended the old wards were converted into halls of residence for Fourah Bay College’s new campus. Up until the civil war began in 1991 the college had done well, gaining university status after forming a link with Durham University in Britain. Leo Blair, whose son Tony was to become British prime minister, worked as an academic at Durham and he came out to Freetown to serve as an exam invigilator several times in the 1960s.

I had been introduced to Prof. Jones during my reporting trips to Sierra Leone, learning to value his erudite and authoritative perspective. When I arrived at his home on a cloudless February morning in 2009, the eighty-four-year-old retired academic spoke with the same warm chuckle I remembered and he began by reminiscing about arriving with the first intake to use the new campus in the abandoned military base.

‘I can remember how we slept in the old hospital wards before they were converted. There was military equipment everywhere and when they were preparing to throw away some of the old machinery from the barracks kitchens I acquired it and we have used it ever since in our garden.’

We were sitting on his lawn and he motioned his hand vaguely towards the herbaceous borders. Peering closely I could see what he was referring to. Large cauldrons on cast-iron pedestals that were once used to prepare meals for legions of British servicemen had been rust-proofed and painted before being decoratively filled with flowering plants.

The professor’s house was in the village of Leicester, one of the first communities set up for ‘recaptives’, high up on Mount Aureol, a mile or so above the university. If his village had strong historical links, his own bloodline read like the genome of Sierra Leone’s freed-slave history. His father’s family were ‘recaptives’ from Nigeria and his mother’s birth certificate described her as a ‘Maroon, Liberated African’. Born in 1925, he had been brought up during Freetown’s golden age when, still under British colonial rule, it was establishing itself as a city many compared to Athens.

‘I was born in a nursing home down on Sackville Street at a time when it was normal for all people in Freetown, black and white, to have access to maternity care. Of course it was not all easy back then. My mother had ten children but only four of us survived to adulthood,’ Prof. Jones explained as we sat in the shade of a tree. His wife of fifty-six years, Marjorie, clucked round him constantly, making sure he was not in the direct sunshine and that our water glasses were full. He continued in the declamatory style of someone well used to lecturing.

‘I went to a grammar school where I was taught by African teachers. And I married Marjorie, whose father was a trained barrister from Sierra Leone who had been recruited to work in another West African country, Gambia. Back then Freetown was the source of professionals who were the pick of the region, taking their skills and expertise from country to country. I studied at Oxford and when I came back to Freetown in 1953 I went to Fourah Bay to teach English literature and never really left. I eventually became Principal in 1974 and served until retirement in 1985.’

I asked about the war. The breezy, hilltop location of Leicester overlooking Freetown appeared wonderful in peacetime but it must have been dangerously exposed when the rebels advanced on the city.

‘We had it all here. There were child soldiers on the road outside, dragging through the dirt guns that were bigger than they were. And at one time we had Nigerian peacekeepers firing from one side and rebels firing from the other. Our neighbour’s house was hit in the crossfire but we escaped unscathed. During all the years of war we only ever left for two weeks when the army, the Sierra Leone army that is, told us to move a mile or so down the hill for our own safety. When we got back some of our property had been stolen and I am pretty sure it was the army that did it.’

There was an air of optimism about Prof. Jones that you rarely find in Freetown and I found it uplifting. Outside the walls of his compound, the road was as pitted and the village as decrepit as many of Freetown’s downtown shanties but inside his house was no different from a much-loved home in British suburbia, albeit with slightly more exotic plant life in the garden. The lawn was trimmed, the borders beautifully arranged and the veranda laid out for maximum enjoyment of a stunning Atlantic panorama.

‘The war was a nightmare, an awful period and it made me feel we had failed as a nation, but we had such strength before that I know we will rise again. We have a history that goes back two hundred years so the nightmare period of war lasting ten years or so is not the norm, and I feel certain we will come good again. The people of Sierra Leone were all over West Africa once as teachers, lawyers and civil servants. They were in demand and they can be in demand again. Yes, there is corruption here and we see it often today but tell me a country where there is not corruption. I know what Sierra Leone has been and I have faith it can be the same again.’

Marjorie was not in complete agreement.

‘Come on, darling. When did we last have power? It’s been three years now, I think, and I cannot remember when we last had water. And both of our children went to live overseas.’

I left them squabbling as warmly as newly-weds. As I walked through their house I had a familiar feeling, as if I were back in the home my grandparents retired to in Kent in the 1970s. The walls were crowded with ethnic pictures and hangings – African for the Joneses, Indian for my mother’s parents – and no surface was free of prized ornaments and knick-knacks. Just as with my grandparents, the whole place felt a tiny bit time-worn as, with age, they struggled to keep on top of the dusting and the maintenance.

In the office a picture on the wall caught my eye. It was a college photograph from Corpus Christi, Oxford, foxed in places by tropical damp and a little washed out in others by sunshine. The year was 1951 and at first glance the students looked very much alike in their stolid tweed jackets and collared shirts. Row after row of faces made lean by rationing looked out from under meticulous partings, many wearing horn-rimmed spectacles, a few racy individuals daring to sport a cravat. And among the ranks of pimply Adam’s apples my eye was drawn to the chubby face of a young Eldred Jones.

‘I was lucky to get one of the first scholarships to Oxford from Sierra Leone, studying English literature as an undergraduate for three years at Corpus from Michaelmas 1950. I had a wonderful time enjoying student life to the full. I acted in the university dramatic society – acting was one of my great loves. And then there was the cricket, another passion from my childhood here in Freetown. I loved cricket so much that when I left school I took a year out and chose a job with the government printing service because it started early but finished early giving me more time for cricket practice.’

I had studied at Oxford myself in the 1980s and, like generations of its students before and since, had felt like I had briefly taken ownership of the place. I had close friends at Corpus and, as a journeyman cricketer, spent many long afternoons playing at the college ground, scene of a turning point in Eldred Jones’s life.

‘I wore glasses at the time but for some reason I had brought the wrong pair that day. We rode our bikes down to the ground as normal. You know how you have to cross the railway to get to the ground, so we parked our bikes on the gravel and crossed the railway on the footbridge.’

I smiled at the thought of the Venn diagrams of our very different lives intersecting. Many times I had used the same footbridge as Eldred Jones to play the same game on the same pitch.

‘My love was batting and that day I went for a pull shot. I am not sure if it was because I could not see properly because of the glasses but I got a top edge and the ball shattered the socket of my right eye. That was the start of my vision problems.’

His sight got steadily worse over the next three decades and by 1986 he was completely blind. I left his house with its academic theses on Shakespeare, Oxford memorabilia and cherished knick-knacks, and went outside, back into the post-war Freetown of potholed roads and decrepit slums. Perhaps it was a blessing Professor Jones could not see what had become of what had once been dreamed of as the Province of Freedom.

Later, on close reading of my first edition of Journey Without Maps, I found Graham Greene had actually met Prof. Jones’s father during the stopover in Freetown in January 1935. The reference had been excised in later editions by Graham Greene, presumably to save space, and Prof. Jones, who had spent his career teaching English literature, had never seen an original edition so did not know of his father’s encounter with one of the most illustrious English authors of the twentieth century. His father had served as a customs inspector at Freetown harbour, the most senior rank then attainable by a native employee under British colonial rules, and had spent time with Graham Greene clearing the disembarkation of the expedition’s equipment. In the original text Graham Greene writes glowingly about Mr Jones, the customs inspector, describing him as one of the few ‘perfectly natural Africans whom I met in Sierra Leone’. It was a feeling I echoed one generation later.