Homework x 2 = The American Dream

ORLANDO, Fla., May 31, 2011 /PRNewswire/—Students from Zhejiang University have been crowned World Champions of the 2011 Association for Computing Machinery International Collegiate Programming Contest. Sponsored by IBM, the competition, also known as the “Battle of the Brains,” challenged 105 university teams to solve some of the most challenging computer programming problems in just five hours. Mastering both speed and skill, Zhejiang University successfully solved eight problems in five hours. The World Champions will return home with the “world’s smartest” trophy as well as IBM prizes, scholarships and a guaranteed offer of employment or internship with IBM. This year’s top twelve teams that received medals are:

• Zhejiang University (Gold, World Champion, China)

• University of Michigan at Ann Arbor (Gold, 2nd Place, USA)

• Tsinghua University (Gold, 3rd Place, China)

• St. Petersburg State University (Gold, 4th Place, Russia)

• Nizhny Novgorod State University (Silver, 5th Place, Russia)

• Saratov State University (Silver, 6th Place, Russia)

• Friedrich-Alexander-University Erlangen-Nuremberg (Silver, 7th Place, Germany)

• Donetsk National University (Silver, 8th Place, Ukraine)

• Jagiellonian University in Krakow (Bronze, 9th Place, Poland)

• Moscow State University (Bronze, 10th Place, Russia)

• Ural State University (Bronze, 11th Place, Russia)

• University of Waterloo (Bronze, 12th Place, Canada)

Hillary Clinton never asked us for career advice. Had she done so, we would have told her this: When President Barack Obama came to you and offered the job of secretary of state, you should have said, “No, thank you. I prefer to hold the top national security job. Mr. President, it would have been wonderful to have been secretary of state during the Cold War, when that job was crucial. True, some things haven’t changed. Now, as in the past, the secretary of state spends all his or her time talking to and negotiating with other governments. Now, as in the past, success depends far less on his or her eloquence than on how much leverage the secretary brings to the table. Now, as in the past, that depends first and foremost on America’s economic vigor. Today, however, more than ever before, our national security depends on the quality of our educational system. That is why I don’t want to be secretary of state, Mr. President. Instead, I want to be at the heart of national security policy. I want to be secretary of education.”

We are well aware of the limits of the power of even the secretary of education when it comes to raising national educational attainment levels. Indeed, we believe that this responsibility belongs to all of us—the whole society. But symbolically the point is correct. Because of the merger of globalization and the IT revolution, raising math, science, reading, and creativity levels in American schools is the key determinant of economic growth, and economic growth is the key to national power and influence as well as individual well-being. In today’s hyper-connected world, the rewards for countries and individuals that can raise their educational achievement levels will be bigger than ever, while the penalties for countries and individuals that don’t will be harsher than ever. There will be no personal security without it. There will be no national security without it. That is why it is no accident that President Obama has declared that “the country that out-educates us today will out-compete us tomorrow.” That is why it is no accident that the executive search firm Heidrick & Struggles, in partnership with The Economist’s intelligence unit, has created a Global Talent Index, ranking different countries, under the motto “Talent is the new oil and just like oil, demand far outstrips supply.”

As a country we have not yet adapted to this new reality. We don’t think of education as an investment in national growth and national

security because throughout our history it has been a localized, decentralized issue, not a national one. Today, however, what matters is not how your local school ranks in its county or state but how America’s schools rank in the world.

Michelle Rhee, the former chancellor of the Washington, D.C., school system, put it this way in an interview in Washingtonian magazine immediately after stepping down from the job (December 2010):

This country is in a significant crisis in education, and we don’t know it. If you look at other countries, like Singapore—Singapore’s knocking it out of the box. Why? Because the number-one strategy in their economic plan is education. We treat education as a social issue. And I’ll tell you what happens with social issues: When the budget crunch comes, they get swept under the rug, they get pushed aside. We have to start treating education as an economic issue.

She is right. Fifty years ago, “education was a choice not a necessity—I can choose to be educated or not, but either way I can get a decent job and live a decent life,” said Andreas Schleicher, the senior education officer at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in Paris. “Today, education is not an option”—it is a necessity for a middle-class standard of living.

Indeed, new jobs, new products, and new services will constantly emerge. But the one thing we know for sure is that with each advance in globalization and the IT revolution, the best jobs will require workers to have more and better education in order to generate that something extra. More and better education may not be sufficient for finding your “extra” and earning a decent living, but for most people it certainly seems to be necessary. Here were the unemployment rates from the Bureau of Labor Statistics for Americans over twenty-five years old in January 2012: those with less than a high school degree, 13.8 percent; those with a high school degree and no college, 8.7 percent; those with some college or an associate degree, 7.7 percent; and those with a bachelor’s degree or higher, 4.1 percent.

“The United States must recognize that its long-term growth depends

on dramatically increasing the quality of its K-12 education system,” wrote Stacey Childress, Deputy Director of Education for the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, in a March 2012 Harvard Business Review essay, “Rethinking School.” But that is not how we are behaving. “Over the past 30 years,” Childress explained, “nearly every labor-intensive service industry in the U.S. has seen dramatic increases in productivity, while public education has become roughly half as productive—spending twice the money per student to achieve the same results.” And while we run in place, others run faster: “In 1990 the U.S. was first in the world in the percentage of 25- to 34-year-olds with college degrees,” she says. “Today it is 10th and dropping.” That is a harrowing statistic when you consider that by 2018 the U.S. Department of Education estimates that nearly half the jobs in America will require a college degree.

Wage statistics reinforce this point. The polarization of employment opportunities in the last three decades “has been accompanied by a substantial secular rise in the earnings of those who complete post-secondary education,” noted Lawrence Katz and David Autor. “The hourly wage of the typical college graduate in the U.S. was approximately 1.5 times the hourly wage of the typical high school graduate in 1979. By 2009, this ratio stood at 1.95. This enormous growth in the earnings differential between college- and high school–educated workers reflects the cumulative effect of three decades of more or less continuous increase.” In November 2010, the Brookings Institution released a study entitled Degrees of Separation: Education, Employment, and the Great Recession in Metropolitan America. The study found that “during the Great Recession, employment dropped much less steeply among college-educated workers than other workers. The employment-to-population ratio dropped by more than 2 percentage points from 2007 to 2009 for working-age adults without a bachelor’s degree, but fell by only half a percentage point for college-educated individuals.” All in all, according to Brookings, while there were some regional discrepancies, “education appeared to act as a pretty good insurance policy for workers during the Great Recession.”

Historically, America has educated its people up to and beyond the technological demands of every era. Lawrence Katz and Claudia Goldin demonstrate in their book The Race Between Education and Technology

that as long as our educational system kept up with the rate of technology change, as it did until around 1970, our economic growth was widely shared. And when it stopped keeping up, income inequality began widening as job opportunities for high school dropouts shrunk while employers bid for a too-small pool of highly skilled workers. Today’s hyper-connected world poses yet another new educational challenge: To prosper, America has to educate its young people up to and beyond the new levels of technology.

Not only does everyone today need more education to build the critical thinking and problem-solving skills that are now necessary for any good job; students also need better education. We define “better education” as an education that nurtures young people to be creative creators and creative servers. That is, we need our education system not only to strengthen everyone’s basics—reading, writing, and arithmetic—but to teach and inspire all Americans to start something new, to add something extra, or to adapt something old in whatever job they are doing.

With the world getting more hyper-connected all the time, maintaining the American dream will require learning, working, producing, relearning, and innovating twice as hard, twice as fast, twice as often, and twice as much. Hence the title of this chapter and the new equation for the American middle class: Homework x 2 = the American Dream.

Since this educational challenge is so important, we will divide our discussion of it into two parts. The rest of this chapter will explore what we mean by “more” education. The next chapter will explain what is required for “better” education.

America needs to close two education gaps at once. We need to close the gap between black, Hispanic, and other minority students and the average for white students on standardized reading, writing, and math tests. But we have an equally dangerous gap between the average American student and the average students in many industrial countries that we consider collaborators and competitors, including Singapore, Korea, Taiwan, Finland, and those in the most developed parts of China.

Some contend that the results of these tests don’t tell the whole story, and that our top students and schools are still as good as any in the world. They are wrong. A study produced for the National Governors Association, entitled “Myths and Realities About International Comparisons,” concluded that the notion that other countries test a more select, elite group of students is wrong. Comparison tests now include a sampling of the whole population in each country. The study, published in The Learning System (Spring 2011), also dispelled the notion that the United States performs poorly in these tests because of poverty and other family factors. In fact, our students are quite similar in socioeconomic conditions to those tested in peer countries. As for the myth that U.S. student attainment cannot be compared to that of other countries because the United States tries to educate many more students, the report noted that the United States does rank above average in access to higher education, but this does not explain the fact that “significantly more U.S. students enter college than the OECD average, but our college ‘survival rate’ is 17 points below the average.” It also doesn’t explain how a country such as Finland, which is not at all diverse, managed to go from the back of the global pack in education to the top. Finland was not diverse when it was mediocre and it was not diverse when it excelled. Diversity was never the issue. Finland vaulted ahead because of specific educational policies. That’s why these tests matter.

And standardized international math and reading tests consistently show that American fourth graders compare well with their peers in countries such as Finland, Korea, and Singapore. But our high school students lag, which means that “the longer American children are in school, the worse they perform compared to their international peers,” the McKinsey & Company consulting firm concluded in an April 2009 report entitled The Economic Impact of the Achievement Gap in America’s Schools. There are millions of students in modern American suburban schools “who don’t realize how far behind they are,” said Matt Miller, one of the report’s authors. “They are being prepared for $12-an-hour jobs—not $40 to $50 an hour.”

Every three years the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) measures how fifteen-year-old students in several dozen industrial countries are being prepared for the jobs of the future by asking them to use their knowledge of math and science to solve real-world

problems and to use their reading skills to “construct, extend and reflect on the meaning of what they have read.”

Here is a sample PISA science question. Test yourself: “Ray’s bus is, like most buses, powered by a petrol engine. These buses contribute to environmental pollution. Some cities have trolley buses: they are powered by an electric engine. The voltage needed for such an electric engine is provided by overhead lines (like electric trains). The electricity is supplied by a power station using fossil fuels. Supporters for the use of trolley buses in a city say that these buses don’t contribute to environmental pollution. Are these supporters right? Explain your answer.”

Here is a sample math question: “A pizzeria serves two round pizzas of the same thickness in different sizes. The smaller one has a diameter of 30 cm and costs 30 zeds. The larger one has a diameter of 40 cm and costs 40 zeds. Which pizza is better value for the money? Show your reasoning.”

Precisely because the PISA test is designed by the OECD to nurture and measure critical thinking and other twenty-first-century workplace skills, the showing of American students in 2009 is troubling. In reading, Shanghai, Korea, Finland, Hong Kong, Singapore, Canada, New Zealand, Japan, and Australia posted the highest scores. American students were in the middle of the pack, tied with those in Iceland and Poland. In math, the American fifteen-year-olds scored below the international average, more or less even with Ireland and Portugal, but lagging far behind Korea, Shanghai, Singapore, Hong Kong, Finland, and Switzerland. In science literacy, the U.S. students again were the middle of the pack, and again lagging behind the likes of Shanghai, Singapore, and Finland. It’s notable that Shanghai, the only city tested in China, did better in math, science, and reading than any of the other sixty-five countries.

Of Shanghai’s performance, Chester E. Finn Jr., who served in the Department of Education during the Reagan administration, told The New York Times (December 7, 2010), “Wow, I’m kind of stunned, I’m thinking Sputnik … I’ve seen how relentless the Chinese are at accomplishing goals, and if they can do this in Shanghai in 2009, they can do it in 10 cities in 2019, and in 50 cities by 2029.” That is the Chinese way: experiment, identify what works, and then scale it. Marc Tucker, the president of the National Center on Education and the Economy, has noted that “while many Americans believe that other countries get better results because those countries educate only a few, while the United

States educates everyone, that turns out not to be true.” Compared to the United States, most top-performing countries do a better job of educating students from low-income families, he said.

As they say in football, “You are what your record says you are.” Our record says that we are a country whose educational performance is at best undistinguished. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan made no excuses for the results. The day the 2009 PISA results were published (December 7, 2010), he issued a statement, saying, “Being average in reading and science—and below average in math—is not nearly good enough in a knowledge economy where scientific and technological literacy is so central to sustaining innovation and international competitiveness.”

The PISA test results got some fleeting newspaper coverage and then disappeared. No radio or television station interrupted its programming to tell us how poorly we had done; neither party picked up the issue and used it in the 2010 midterms. Partial-birth abortion received more attention. The president did not make a prime-time address. The twenty-first-century equivalent of Sputnik went up—and yet very few Americans seemed to hear the signal it was sending.

Susan Engel, a senior lecturer in psychology and director of the teaching program at Williams College and the author of Red Flags or Red Herrings? Predicting Who Your Child Will Become, frames our challenge this way: “There are two basic problems with education in America. The first glaring problem, the one getting lots of attention, is that too many kids have no choice but to go to schools that are dangerous, badly staffed, educationally indifferent, and underfunded. If you take those kids and put them in a school with reasonable funding, a school board and an administration that are excited about what is happening, and with energetic teachers, it’s a huge improvement over what those kids have had. So, problem one: too many kids in America go to schools that don’t even begin to offer them the hope of getting to average.”

Our second problem, explains Engel, is just as big, if not bigger. It’s that “even the ‘nice’ schools aren’t good enough. These schools have decent facilities, adequate class sizes, a good number of teachers who like their job and/or like kids, and a majority of students who can read, who can pass standardized state tests. These schools are often okay, but not really good. Too many teachers are not that well educated, not that on fire to be teachers, and not that challenged within the system to be terrific. Such schools often lack any coherent or compelling idea about what a good education consists of, what high schools should emphasize, how to be really vibrant learning communities. These ‘okay’ schools may send kids like yours and mine on a good path—good colleges, good job options—but even in these schools, too many kids are not living up to their intellectual or personal potential. They’re not engaged, and not headed to become the inventors, entrepreneurs, and stewards of the Earth that we’re going to need.”

PISA focuses on young people’s ability to use their knowledge and skills to meet real-life challenges. This orientation reflects a change in the goals and objectives of curricula themselves, which are increasingly concerned with what students can do with what they learn at school and not merely with whether they have mastered specific curricular content.

Source: OECD PISA 2009 database

According to the Department of Education, about a third of first-year students entering college had taken at least one remedial course in reading, writing, or math. The number is even higher for black and Hispanic students. At public two-year colleges, that average number rises to above 40 percent. And having to take just one remedial course is highly correlated with failure to graduate from college.

Engel’s point cannot be emphasized enough: We must close the gap between minorities and average whites, because there are virtually no jobs that will provide a decent standard of living anymore for those who can’t get some form of post–high school education, let alone a decent high school education that imparts critical thinking, reading, and basic math skills. But we also have to raise the whole American average, because even if the achievement levels of black and Hispanic young people can rise to the level of average white students but our average is in the middle of the world pack, we will not have the critical mass of workers necessary to do the best jobs, let alone invent new ones. Making a Harlem school perform as well as a Scarsdale school is necessary, but only getting both schools to perform as well as or better than a school in Shanghai is insufficient. We need to close the gap between our achievement and our potential today, but our long-term economic vitality depends on raising the potential of our entire society tomorrow. We need to lift the bottom faster and the top higher.

We also need more routes to the top. Many of the good jobs opening up in this country do not require four years of college, but they do require high-quality vocational training. Learning to repair the engine of an electric car, or a robotic cutting tool, or a new gas-powered vehicle that has more computing power in it than the Apollo space capsule—these are not skills you can pick up in a semester of high school shop class. It is vital that high schools and community colleges offer vigorous

vocational tracks and that we treat them with the same esteem as we do the liberal arts or “college” tracks. Maybe we don’t have to channel students as formally as do Singapore, Finland, and Germany—where early in high school students move either onto a track for four-year college or into vocational training of two or more years—but we do need to make clear that everyone needs postsecondary education, that there is a range of opportunities, that students need to start preparing for those different opportunities in high school, and, ultimately, that learning how to deconstruct a laptop computer in the local community college is as valuable as learning how to deconstruct The Catcher in the Rye at the state university.

A high school education today, says Duncan, should prepare a student to attend a university or a vocational college “without remediation,” because that is the ticket to a decent job. Until now the goal has just been “to get people to graduate” from high school, he added. But graduation alone is not enough. There are too few decent jobs for such people anymore, and few or none for the young person without a high school degree. A high school education must prepare students for the next step of education or skill-building. “That’s the fundamental shift,” said Duncan. “We should have made that shift twenty-five years ago. But we didn’t, so we have to catch up.”

We do not know the exact mix of policies that is needed for “more” education, a subject on which there are many views. That is, we don’t know if we need more charter schools or just more effective public schools. We don’t know if we need a longer school day or a longer school year, or both or neither. We do not know which technologies or software programs are best at training students so that we see a rise in math abilities and test scores. We don’t know to what extent teachers’ unions are the problem, by protecting the jobs of mediocre teachers, and to what extent they are part of the solution, in rewarding great teaching. We leave to the educational experts the definition of what is sufficient in all these areas to produce more education for all.

We do, though, think we know what is necessary to produce more students who are ready to succeed in postsecondary education and the job market. We believe that six things are necessary: better teachers and better principals; parents who are more involved in and demanding of their children’s education; politicians who push to raise educational standards, not dumb them down; neighbors who are ready to invest in

schools even though their children do not attend them; business leaders committed to raising educational standards in their communities; and—last but certainly not least—students who come to school prepared to learn, not to text.

If that list strikes you as including everyone in society, you’ve gotten the point. Our education challenge is too demanding for the burden to be borne by teachers and principals alone. Let’s look at each group.

While teachers and principals cannot be expected to overcome our education deficits alone, outstanding teachers and principals can make a huge difference in student achievement. So we need to do everything we can as a society to recruit, mentor, and develop the best cadre of teachers and principals that we can. Bill Gates, whose Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation invests heavily in studying and improving K–12 public school education, says its research shows that “of all the variables under a school’s control, the single most decisive factor in student achievement is excellent teaching. It’s astonishing what great teachers can do for their students. Unfortunately, compared to the countries that outperform us in education, we do very little to measure, develop, and reward excellent teaching. We need to build exceptional teacher personnel systems that identify great teaching, reward it, and help every teacher get better. It’s the one thing we’ve been missing, and it can turn our schools around … But the remarkable thing about great teachers today is that in most cases nobody taught them how to be great. They figured it out on their own.”

Eric A. Hanushek, a senior fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, summarized some of the findings of his research on the importance of quality of teaching in Education Week (April 6, 2011):

Studies examining data from a wide range of states and school districts have found extraordinarily consistent results about the importance of differences in teacher effectiveness. The research has focused on how much learning goes on in different classrooms. The results would not surprise any parent. The teacher matters a lot, and there are big differences among teachers.

What would surprise many parents is the magnitude of the impact of a good or bad teacher. My analysis indicates that a year with a teacher in the top 15 percent for performance (based on student achievement) can move an average student from the middle of the distribution (the 50th percentile) to the 58th percentile or more. But that implies that a year with a teacher in the bottom 15 percent can push the same child below the 42nd percentile … Obviously, a string of good teachers, or a string of bad teachers, can dramatically change the schooling path of a child … The results apply to suburban schools and rural schools, as well as schools serving our disadvantaged population.

Why doesn’t this issue get more attention? “First,” answers Hanushek, “it is likely that ineffective teachers are generally hidden, in the sense that few kids get a string of bad teachers. Principals know very well who the ineffective teachers are, so they can balance a bad teacher one year with a good teacher the next. This implicit averaging process also means that it does not look like schools can do much to alter family background and what the child brings to school. Second, parents do not quite know how to interpret results on achievement tests. The teachers’ unions have, since the advent of the No Child Left Behind Act in 2002, conducted a campaign to convince people that these scores do not really matter very much. Here they are flatly contradicted by the evidence.”

Achievement in school matters, and it matters for a lifetime. “Somebody who graduates at the 85th percentile on the achievement distribution can be expected to earn 13 percent to 20 percent more than the average student,” writes Hanushek. “This applies every year throughout a person’s working life, yielding a difference in present value of earnings of $150,000 to $230,000 on average … By conservative estimates, the teacher in the top 15 percent of quality can, in one year, add more than $20,000 to a student’s lifetime earnings, my research found … For a class of 20 students, we see that this very good teacher is adding some $400,000 in value to the economy each year.” A bad teacher in the bottom 15 percent is subtracting the same amount.

What are the best school systems in the world doing to attract and retain the best teachers and principals, and how do we introduce similar

reforms here? To answer the question, McKinsey produced a study entitled How the World’s Best-Performing School Systems Come Out on Top (September 2007). It looked at the world’s ten best-performing school systems, such as Finland’s and Singapore’s, and compared them to less accomplished ones. The study’s key findings are these: Most people who become teachers in these successful countries come from among the top 10 percent of their high school or college graduating classes; university students see the teaching profession as one of the top three career choices; the ratio of applications to available places in initial teacher-education courses in these countries is roughly ten to one; starting salaries for teachers in the successful countries are in line with other graduate salaries; teachers in these successful countries spend about 10 percent of their time on professional development—far higher than in America—and these same teachers regularly invite one another into their classrooms to observe and coach; finally, there are clear standards for what students should know, should understand, and should be able to do at each grade level.

The report’s conclusions: The quality of an education system cannot exceed the quality of the teachers. The only way to improve outcomes is to improve instruction. Achieving universally high outcomes is only possible by putting in place mechanisms to ensure that schools deliver high-quality instruction to every child.

The McKinsey report did not evaluate principals, but they, too, are vitally important to student achievement. And finding ways to evaluate principals has to be part of any educational reform program. A principal’s ability to recruit and retain great teachers, improve the effectiveness of all teachers, and, most important, to serve as an inspirational leader to bring out the best in teachers and students must be part of any evaluation process for any school system. As any teacher can tell you, the difference that a good or bad principal can make for an entire school is enormous. Tony Wagner, the Innovation Education Fellow at the Technology and Entrepreneurship Center at Harvard, argues that America should create a West Point for would-be teachers and principals: “We need a new National Education Academy, modeled after our military academies, to raise the status of the profession and to support the R and D that is essential for reinventing teaching, learning, and assessment in the twenty-first century.”

America cannot introduce needed reforms with one wave of the wand from Washington—not with our decentralized system of public education, which is composed of some 14,000 independent school districts. We can, however, produce successful local and regional models for education that can be imitated nationwide, models that can overcome the tension between teachers’ unions, school administrators, and politicians to raise students’ educational attainment. One such reform model is Colorado’s.

To learn more about public education in Colorado, we interviewed Michael Johnston, the state senator who helped to found New Leaders for New Schools, an organization dedicated to training and recruiting leaders for urban schools, and who played a leading role in his state’s reform initiative. In 2005, he co-founded Mapleton Expeditionary School of the Arts, a public school for disadvantaged youth in Thornton, Colorado. As the school’s principal, he oversaw substantial progress in the school’s performance, taking a school with a dropout rate of 50 percent and turning it into the first public high school in Colorado to have 100 percent of seniors admitted to four-year colleges. In a state that has a 25 percent dropout rate—50 percent among blacks and Hispanics—every little bit helps, but the need to scale the programs that work is urgent.

A unique feature of Johnston’s public school was that the district gave him a free hand to put together his own teaching staff. In 2010, after being appointed to the Colorado state senate, he sought to build on that experience and teamed up with the governor, community leaders, and some members of the teachers’ union to shepherd through a pathbreaking teacher quality act (SB 10-191), known as the Great Teachers and Leaders Bill. While many social and economic factors shape student performance, Johnston’s approach begins with the conviction that within the schools themselves, nothing is more important than the quality of the teachers and principals.

“When I am talking to teachers,” Johnston says, “I always begin by saying, ‘First, we all share the same mission: We all want to close the achievement gap, graduate all of our students, and send them to college or a career without the need for remediation.’ But we know that we’re

talking about a problem, an education deficit, of massive proportion. If you’re going to solve a problem that big, you need a lever as big as the problem. And what we now know is that the single most important variable determining the success of any student is the effectiveness of the teacher in that classroom. That impact is so significant that when you talk about curriculum, professional development, or even class size, those changes are literally rounding errors compared to the impact of a great teacher.” He goes on to say: “If you take our lowest-performing quartile of students and you put them in the classroom of a highly effective teacher, we know that in three years you have nearly closed the achievement gap. And we know that the opposite is true. If you take the lowest quartile of students and put them in the classroom of our least effective teachers and principals, you will blow that achievement gap open so wide you’ll never close it.

“As in all professions, we know there are real differences in the effectiveness of teachers from classroom to classroom,” Johnston says. “We know that people spend endless hours in the real estate market shopping for houses based on the school their kids might attend. But what actually matters is not what school you walk into but what classroom you walk into. Because we know that the difference in performance between teachers in any given school is twice as large as the difference in performance between schools. You could buy a house in the worst neighborhood in Denver and have a highly effective teacher for your child and you would be much better off than someone who bought a house in the wealthiest neighborhood of Denver and their kid was assigned to an ineffective teacher.”

We now have the data to identify teachers who are making three years of gains in the classroom in one year’s time. But we don’t have a pipeline—from college, to school placement, to teacher evaluation, to pay and promotion systems—that delivers anything like the number of good teachers that we need. The superb ones we have, says Johnston, “are more like flowers that have willed their way up through concrete,” rather than flowers grown in abundance in “hothouses” designed to produce them at that scale.

That is hardly surprising, he added, when you think of what we have asked teachers to do. “When I was twenty-one years old, I was a first-year high school teacher, and I taught six sections of Julius Caesar to ninth

graders each day,” said Johnston. “In the room across the hall was a teacher who was sixty-two years old and she taught six sections of Julius Caesar each day. That was the career path that I was being offered. This is why we lose 50 percent of teachers in the first three to five years.”

Teachers come in loving the idea of sharing literature with young minds, said Johnston, and then they discover that there is no real potential for job growth unless they leave the classroom, very little ongoing professional development, inconsistent evaluation or feedback, and limited opportunities to interact with colleagues who are serious about reflecting on and improving their practice.

The same is true with principals. Other than the classroom teacher, the principal is the most important person in that school building. “What we see around the country,” said Johnston, “is that great principals attract and retain great teachers. Terrible principals drive out great teachers. What is amazing is that the system retains as many good teachers as it does,” given the uneven quality of principals.

“We are not focusing on teachers because teachers are the problem,” said Johnston. “It’s because they are the solution.” When you look at the data on the difference that great teachers can make “you realize that they are such high-leverage instruments that a small move of the lever produces exponential results in student achievement.” That means building systems that attract and retain more of the top teachers and improve or weed out more of the weaker teachers, which could thereby lead to a system-wide change in the quality of teaching. The Great Teachers and Leaders Bill, signed into law by Colorado governor Bill Ritter on May 20, 2010, aims to accomplish just that goal and is built on five principles.

First, explains Johnston, “we make 50 percent of every teacher’s and principal’s performance evaluation based on demonstrated student growth—and ‘growth’ is the key word. It doesn’t matter what level the kids start at on September 1, we want to see that they know substantially more when they walk out the door on May 30. We are now developing, in consultation with teachers and principals, the metrics for these assessments. This is not meant as ‘gotcha!’”

Indeed, it is vitally important to have a teacher-evaluation system, but also a system that teachers help to design and believe is fair. The Colorado evaluation process will include some combination of student

survey data, principal reviews, and test results, and could include master-teacher reviews or peer-educator reviews, along with a chance for teachers to show themselves at their best—not just on surprise visits by inspectors.

Second, said Johnston, “we establish career ladders for teachers and principals who are identified as highly effective. We say to them, ‘We want to learn what you are doing, and we will pay you a stipend on top of your salary to document and share with other teachers what you are doing that is making you successful.’ So we might identify the twenty best math teachers in the state and would then pay them a stipend to video their classrooms when they are teaching a lesson and to upload their lesson plans onto a website. Then, if I am a new seventh-grade teacher, I can go on to the Web, click on ‘seventh-grade math,’ click on a specific standard, and see how our most effective teachers teach that particular standard. Or I can use the same website to identify master teachers and sign up to actually go visit their classrooms, where I can sit in the back and watch them practice in real time in front of students.”

This not only gives all teachers a chance to learn from their best colleagues but also, added Johnston, creates “an incentive for our best teachers to stay in the classroom. Right now, as a teacher, the only way to get substantially more pay is to leave the classroom and become a principal. Now you have another career ladder.”

In China, for instance, there are four levels of proficiency in the teaching profession, and in order to move up a level, teachers have to demonstrate their excellence in front of a panel of reviewers. The highest level is called “Famous Teacher.” It is a hugely prestigious position in China.

Third, tenure in Colorado will be based on performance rather than seniority. That is, tenure, while not eliminated, will have to be earned and re-earned. Rather than being granted permanent tenure on the first day of his or her fourth year, now a teacher will have to earn tenure by producing three consecutive years of being rated an “effective” teacher. That teacher will then have to continue performing effectively to keep that status. If you are rated “ineffective” for two years, you lose your tenure. That does not mean you lose your job; it just means you are on a one-year contract.

That leads to the fourth principle: In Colorado the old law for teachers stipulated that in the event of cutbacks, the last hired were first to be fired, even if that was not in the best interest of the school or the students. Not anymore. “Now,” explains Johnston, “the law says that whenever principals have to make reductions in force, the first criterion is ‘teacher effectiveness.’ You have to keep your most effective teachers. And only in the event of a tie does seniority kick in. An effective second-year teacher trumps an ineffective twentieth-year teacher.”

The fifth principle gives principals the power to hire their own teachers. That is, the school district cannot take ineffective teachers, whom no school wants to hire, and force them on a school. Teachers who are not hired by any school on their merits after one year get released.

How in the world did they get this bill passed, given all the oxen it gored? “We made the case to all the groups involved as to why this was really in their interest,” said Johnston. He and his political allies showed the NAACP how school systems were dumping their worst teachers in predominantly black and Hispanic schools. They showed business leaders and the chamber of commerce how subpar students were leading to subpar employees. They went to the two big teachers’ unions in Colorado, said Johnston, “and we said, ‘You all know that you have some great colleagues and colleagues that you have been carrying for years. There is no reason to do that anymore.’”

The key breakthrough for Johnston, though, was getting the American Federation of Teachers (AFT), led by Randi Weingarten, to support the legislation. Weingarten staked out a gutsy position. The National Education Association, the other big teachers’ union, opposed the law, although a number of NEA union representatives in Colorado broke ranks and testified for the bill.

Weingarten, the president of the 1.5 million–member AFT, explained to us why her union supported the Colorado reform. For her and her union members, she said, the key question was how teachers get evaluated. They understood that the old system of granting automatic tenure was not sustainable. But some of the new systems—in which, for example, a teacher has five unannounced evaluations of thirty minutes each by a master teacher or principal, and virtually their entire evaluation is based on those brief visits and the students’ standardized test scores—are too limited, she argued.

“We need evaluation systems based on multiple measures of both teacher practice and what students are learning,” said Weingarten. In Colorado, she added, teachers and administrators “spent a lot of time talking to each other about how to make this evaluation system about continuous improvement, and that was why at the end of the day we supported the legislation.” In that Colorado bill, “there was a teacher voice in how to make schools better,” she added. “There was a lot of flexibility in what constituted acquisition of student learning—so it was not just test scores—and there was a lot more due process ensuring that teachers had a fair shake put into that law.”

As Johnston put it: “What we got is a bill that requires multiple measures of student growth, that allows teachers multiple opportunities to improve, and doesn’t ever force-fire anyone but always leaves that decision to principals and superintendents.”

Johnston said that when he thinks about the change that he and others are trying to effect in education, he thinks back to attending President Obama’s inauguration in Washington. What impressed him most was seeing a platoon of wheelchairs parting the crowd on the Mall after the president took the oath. Sitting in them were the surviving Tuskegee Airmen, the first African American aviators in the United States armed forces, who flew many successful missions in World War II.

“What I realized was that they lived in a moment when people didn’t believe it was possible—they didn’t believe that a black man had the courage or intelligence or stamina to fly one of America’s most expensive warplanes,” Johnson recalled. “So they said, ‘Put me up in the air and let me show you,’ and they became one of the only air squadrons in World War II who never lost a bomber.” And of course they could and did become successful pilots. “And when they did, the world changed—because the argument about whether or not we were all created equal was once and for all over, and nothing else could have happened but that Truman would eventually integrate the air force, or that Johnson would sign the Civil Rights Act, or that sixty years later we would inaugurate the first black president.

“Education needs its own Tuskegee moment. One reason we have not been able to galvanize the whole community for educational reform,” Johnston concluded, “is that some people still don’t believe that every one of our kids can compete with the smartest kids from Singapore

and China. It’s our responsibility to get up in the air and prove them wrong. Then the whole world changes.”

As we noted earlier, if we want to make every teacher more effective, the rest of us need to be more supportive. This is not an argument for going easy on teachers. It is an argument for not going easy on everyone else. We must not do to teachers and principals what we did to the soldiers and officers in Iraq and Afghanistan after 9/11: put the whole effort on their backs while the rest of us do nothing except applaud or criticize from the sidelines. Here is how everyone has to contribute.

Communities: If we want teachers to raise their effectiveness, communities not only have to create an effective reform process that all the key players want to own; they also have to find ways to reward teachers through nonmonetary means. Teaching is a hard job. Unions or no unions, we’d bet that most teachers work more hours for no pay than any other professionals. No one goes into teaching for the money, and thousands of teachers every year dig into their own pockets to buy classroom materials. If teachers are so important—and great teachers are—how about recognizing and celebrating the best of them regularly in your community with something more than a $50 gift certificate from the PTA?

How? Here’s an example. On November 1, 2010, the D.C. Public Education Fund, the nonprofit fund-raising arm of the Washington, D.C., public school system, organized “A Standing Ovation for D.C. Teachers” to honor the 662 instructors judged “highly effective” under the city’s new IMPACT evaluation system, to which teachers had agreed. The tribute was produced by George Stevens Jr., producer of the annual Kennedy Center Honors, and had all the glitz of an Academy Award ceremony for teachers. Those 662 teachers had been singled out from their schools as highly effective. It was clearly a special evening for all of them. Before he sang, one of the performers, Dave Grohl of Nirvana and the Foo Fighters, recalled the teacher who had most influenced his life: his mother, who had taught in a Virginia public school for thirty-five years. “She was up before the sun every day, grading papers, and every night when it went down,” said Grohl. Seven teachers, nominated

by their principals, were singled out as All-Stars. Each came onstage to receive a plaque and a $10,000 award (all 662 got performance bonuses), and to deliver an acceptance speech. Kennedy Center chairman David Rubenstein was so moved by the event that he donated twenty more $5,000 awards on the spot. Not every community has access to the Kennedy Center, but every community can do more to make teachers feel appreciated and to inspire excellence.

For instance, every year, in addition to granting honorary degrees, Williams College in Massachusetts honors four high school teachers. But not just any high school teachers. Williams asks the five hundred or so members of its senior class to nominate the high school teacher who had the most profound impact on their lives. Then each year a committee goes through the roughly fifty student nominations, does its own research with the high schools involved, and chooses the four teachers who most inspired a graduating Williams student. Each of the four teachers is given $3,000, plus a $2,500 donation to his or her high school. The winners and their families are then flown to Williams, located in the lush Berkshires, and honored as part of the college’s graduation weekend. On the day before graduation, all four of the high school teachers, and the students who nominated them, sit onstage at a campus-wide event, and the dean of the college talks about how and why each teacher influenced that Williams student, reading from the students’ nominating letters. Afterward, the four teachers are introduced at a dinner along with the honorary-degree recipients. Morton Owen Schapiro, now the president of Northwestern but formerly the president of Williams, recalled that every time he got to preside over these events one of the high school teachers would say to him, “This is one of the great weekends of my life.” When you get to work at a place like Williams, Schapiro added, “and you are able to benefit from these wonderful kids, sometimes you take it for granted. You think we produce these kids. But as faculty members, we should always be reminded that we stand on the shoulders of great high school teachers, that we get great material to work with: well educated, well trained, with a thirst for learning.”

A variation on this theme that has been running since 1978 is the Yale–New Haven Teachers Institute, directed by James R. Vivian. It brings together Yale faculty members and New Haven public school

teachers for seminars in the faculty members’ subjects of expertise. In the seminars, which meet regularly for several months, the teachers work with a faculty member to prepare curricula on the subject they are studying, which they then teach in their schools during the following school year. The seminars thus give the teachers the opportunity both to learn more about a subject of interest—chemistry, mathematics, literature, American history, or another of many different offerings—and to prepare strategies to teach it to their elementary or secondary school students. They also receive a modest honorarium for participating. The program has enjoyed such success that twenty-one different school districts in eleven states are now participating in the Yale National Initiative to strengthen teaching in public schools, which the Institute launched in 2004. The Initiative is a long-term effort to establish similar Institutes around the country and to influence public policy on the professional development of teachers.

Teachers’ institutes differ from most of the programs of professional development that school districts provide and from outreach and continuing education programs that universities typically offer in that schoolteachers and university faculty members work together as professional colleagues, in a program that is led in crucial respects by the teachers themselves. This not only improves the teachers’ classroom performance; it also serves a purpose as important as recruiting and training good teachers: keeping them.

At the Annual Conference held at Yale on October 29, 2010, James Foltz, who teaches English at Middletown High School in Delaware, said this about participating in the Institute: “Recently my wife asked me, ‘How long do you think you can keep teaching?’ If she had asked me this one year ago, my answer might have been a few more years, maybe five at the most. My answer is just a little bit different now, and it extends from my experience here at Yale … We talk all the time about how we need to inspire our students, and we do, but once in a while we forget that we also need to inspire our teachers.”

By the way, very few people go into teaching for the money, but many people leave teaching because of the money—especially men. If we really want to show our appreciation for teachers, we need to find innovative ways to pay them more.

Politicians: If we want better teachers, politicians will have to become

better educators. They have to educate the country about the world in which we’re living, about the vital role education now plays for our economy and our national security, about why raising standards is imperative, and about the skills that students need to acquire. They need to understand that part of their job is traveling around the country, and even the world, to understand the best practices in education so that they can both lead and inform the debate about these issues in their communities. It is vital to our economic growth.

State officials should be competing with one another to raise their educational standards and to demonstrate creativity in using education dollars. For a while, just the opposite was going on. When Congress passed the No Child Left Behind Act of 2002, it mandated that students had to achieve certain standards each year for their schools to benefit from federal funding, but it left it to each state to determine those standards. In recent years, as those standards remained unmet, many states simply lowered them to make it easier for students to pass tests and for schools to avoid the penalty of lost funding or being labeled a “failing school.” Nothing could be more dangerous in today’s world.

In response, in 2009 the National Governors Association and the Council of Chief State School Officers initiated a nationwide effort to set common standards, enlisting experts in English and math from the College Board and the ACT, and from Achieve, Inc., a group that has long pushed to firm up high school graduation standards. This effort was reinforced by the Department of Education’s Race to the Top initiative, in which states were invited to compete for a share of $4 billion in school improvement money by showing a path to raising academic achievement. States competing in Race to the Top earned extra points for participating in the common effort to establish national standards and then adopting them.

Arne Duncan often complains that one of his biggest challenges as secretary of education is that too many Americans believe that their local schools are basically fine and that it is someone else’s school that needs fixing. One reason people feel this way is that they are comparing their school with the one in the neighborhood or district next door. The relevant comparison is between their school and P.S. 21 in south Taipei or north Seoul or west Shanghai. This will become apparent when their children apply to college and find themselves competing

with the graduates of those schools. Good enough is just not good enough anymore.

“One thing that has been missing is honesty,” said Jack Markell, the governor of Delaware, which was one of the first two states to win Race to the Top funds (Tennessee was the other) and has been a leader in the national standards-writing initiative. “When you tell the kids they are proficient based on a test that is administered within their state borders, while in the real world they have to compete for college and for jobs with kids who are not within their state borders, you are not being honest with them. In our old test, 76 percent of Delaware fourth graders were judged to be proficient in reading. With our new test and scoring, that will be 48 percent, because we are being more honest with the kids about what it means to be more proficient.”

How does he sell this reform to skeptical Delaware residents? He does it by connecting education with jobs. “I went to Taiwan a month ago,” Markell told us in January 2011. “We have two Taiwanese companies in Delaware with 250 employees between them. One of the companies makes solar panels. At the same time that they started in Delaware, they started a factory in China. There is only one thing I am asking myself: ‘Where are they going to invest their next dollars?’ And you have to put yourself in their shoes. It is going to go where it will have the best return.” And part of that, added Markell, will depend on where they find the most productive workers. This is not just about cheap labor. It is about skilled labor.

Neighbors: The role of neighbors today is to appreciate the importance of the public school down the street, even if their own children have long graduated or they have no children at all. Good schools are the foundation of good neighborhoods and communities. Money may be saved in the short term by voting down tax increases to fund schools. But if that results in higher dropout rates and higher unemployment, the overall cost to the community will certainly be higher. When the performance of local schools drops, it usually is not long before the value of nearby houses drops as well. In March 2010, Tom attended the Intel Science Talent Search, a national contest for high school students designed to identify and support the nation’s next generation of scientists. “My favorite chat was with Amanda Alonzo, a thirty-year-old biology teacher at Lynbrook High School in San Jose, California,” he wrote at the time.

“She had taught two of the [Intel] finalists. When I asked her the secret, she said it was the resources provided by her school, extremely ‘supportive parents,’ and a grant from Intel that let her spend part of each day inspiring and preparing students to enter this contest. Then she told me this: Local San Jose Realtors are running ads in newspapers in China and India telling potential immigrants to ‘buy a home’ in her Lynbrook school district because it produced ‘two Intel science winners.’” While every child’s educational experience should matter to everyone as a matter of principle, good education is also good economics—for everybody.

McKinsey & Company made that very point in its report entitled The Economic Impact of the Achievement Gap in America’s Schools (April 2009). The report asked what would have happened if in the fifteen years after the 1983 report A Nation at Risk sounded the alarm about the “rising tide of mediocrity” in American education, the United States had lifted lagging student achievement. The answer: If black and Latino student performance had caught up with that of white students by 1998, GDP in 2008 would have been between $310 billion and $525 billion higher. If the gap between low-income students and the rest had been narrowed, GDP in 2008 would have been $400 billion to $670 billion higher.

“We simply don’t have the capacity to carry large pockets of our population, whom we know are unskilled and have a life that has a ceiling on it, and think that the United States can still soar and be unique and be the number-one source of good in the world,” Kasim Reed, the mayor of Atlanta, told us.

Parents: In January 2011, Yale University law professor Amy Chua set off a firestorm of debate across America when The Wall Street Journal published an excerpt from her book Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother. While Chua’s child-rearing strategy was extreme and her book evoked a sharp backlash from many parents and educators, we think she ignited a useful debate. It was a wake-up call. Whatever you think of Chua’s ironfisted parenting style, we urge you to keep this in mind: She is not alone in her parenting methods, and her approach is not at all rare in Asian culture. It is the norm.

“A lot of people wonder how Chinese parents raise such stereotypically successful kids,” wrote Chua.

Well, I can tell them, because I’ve done it. Here are some things my daughters, Sophia and Louisa, were never allowed to do: attend a sleepover, have a playdate, be in a school play, complain about not being in a school play, watch TV or play computer games, choose their own extracurricular activities, get any grade less than an A, not be the No. 1 student in every subject except gym and drama, play any instrument other than the piano or violin, not play the piano or violin … Even when Western parents think they’re being strict, they usually don’t come close to being Chinese mothers … Studies indicate that compared to Western parents, Chinese parents spend approximately 10 times as long every day drilling academic activities with their children … The Chinese believe that the best way to protect their children is by preparing them for the future, letting them see what they’re capable of, and arming them with skills, work habits and inner confidence that no one can ever take away.

We would not expect every parent to mimic Chua in the tough-love department; there is a fine line between involved parenting and making your kid neurotic, which even Chua acknowledges. In general, though, we believe Chua is right about two things: the need to hold children to the highest standards that push them out of their comfort zones, and the need to be involved in their schooling. When children come to school knowing that their parents have high expectations, it makes everything a teacher is trying to do easier and more effective. Self-esteem is important, but it is not an entitlement. It has to be earned.

Arne Duncan tells a story from President Obama’s 2009 trip to South Korea to drive home that point to American parents: “President Obama sat down to a working lunch with South Korean president Lee in Seoul. In the space of little more than a generation, South Korea had developed one of the world’s best-educated workforces and fastest-growing economies. President Obama was curious about how South Korea had done it. So he asked President Lee, ‘What is the biggest education challenge you have?’

“Without hesitating, President Lee replied, ‘The biggest challenge I have is that my parents are too demanding.’”

That anecdote usually makes Americans chuckle, says Duncan—and then wince. The president of Korea’s parents are complaining that he hasn’t done enough with his life.

“I wish my biggest challenge—that America’s biggest educational challenge—was too many parents demanding academic rigor,” said Duncan. “I wish parents were beating down my doors, demanding a better education for their children, now. President Lee, by the way, wasn’t trying to rib President Obama. He explained to President Obama that his biggest problem was that Korean parents, even his poorest families, were insisting on importing thousands of English teachers so their children could learn English in first grade—instead of having to wait until second grade.”

American young people have got to understand from an early age that the world pays off on results, not on effort. Not everyone should win a prize no matter where he or she finishes. Indeed, America today reminds us a little too much of that scene in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland in which the Dodo is organizing a race:

First it marked out a race-course, in a sort of circle, (“the exact shape doesn’t matter,” it said), and then all the party were placed along the course, here and there. There was no “One, two, three, and away,” but they began running when they liked, and left off when they liked, so that it was not easy to know when the race was over. However, when they had been running half an hour or so, and were quite dry again, the Dodo suddenly called out “The race is over!” and they all crowded round it, panting, and asking “But who has won?”

This question the Dodo could not answer without a great deal of thought, and it sat for a long time with one finger pressed upon its forehead (the position in which you usually see Shakespeare, in the pictures of him), while the rest waited in silence.

At last the Dodo said “Everybody has won, and all must have prizes.”

All must have prizes! Krista Taubert is the Washington-based correspondent for Finnish Broadcasting Company. She has two children in the Washington, D.C., school system, a nine-year-old and a five-year-old. Since Finland has one of the highest-rated school systems in the

world and Tom met her at a movie about Finland’s schools, he could not resist asking her to compare her daughters’ educational experiences in America and in Finland.

In America, Taubert remarked, “I noticed sometimes in talking to other parents that they reward their kids for effort, not for excellence. My daughter plays soccer and as a nine-year-old she already has these huge trophies, and she actually hasn’t won anything. My brother played professional hockey in Finland for a number of years, and he doesn’t have any trophies as big as the trophies my daughter has.”

Andreas Schleicher oversees the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), to which we referred earlier. The program is administered by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), a Paris-based group that includes the world’s thirty-four major industrial countries. As noted, it tests fifteen-year-olds in the world’s leading industrialized nations on their reading comprehension and ability to use what they’ve learned in math and science to solve real problems—the most important skills for succeeding in college and life. Schleicher told us that in order to understand better why some students thrive taking the PISA tests and others do not, he was encouraged by the OECD countries to look beyond the classrooms. So starting with four countries in 2006, and then adding fourteen more in 2009, the PISA team went to the parents of 5,000 students and interviewed them “about how they raised their kids and then compared that with the test results” for each of those years, said Schleicher. In November 2011, the PISA team published the three main findings of its study:

Fifteen-year-old students whose parents often read books with them during their first year of primary school show markedly higher scores in PISA 2009 than students whose parents read with them infrequently or not at all. The performance advantage among students whose parents read to them in their early school years is evident regardless of the family’s socioeconomic background. Parents’ engagement with their 15-year-olds is strongly associated with better performance in PISA.

Schleicher explained that “just asking your child how was their school day and showing genuine interest in the learning that they are

doing can have the same impact as hours of private tutoring. It is something every parent can do, no matter what their education level or social background.” For instance, the PISA study revealed that “students whose parents reported that they had read a book with their child ‘every day or almost every day’ or ‘once or twice a week’ during the first year of primary school have markedly higher scores in PISA 2009 than students whose parents reported that they had read a book with their child ‘never or almost never’ or only ‘once or twice a month.’ On average, the score difference is 25 points, the equivalent of well over half a school year.” Yes, students from more well-to-do households are more likely to have more involved parents. “However,” the PISA team found, “even when comparing students of similar socioeconomic backgrounds, those students whose parents regularly read books to them when they were in the first year of primary school score 14 points higher, on average, than students whose parents did not.” The kind of parental involvement matters, as well. “For example,” the PISA study noted, “on average, the score point difference in reading that is associated with parental involvement is largest when parents read a book with their child, when they talk about things they have done during the day, and when they tell stories to their children.” The score-point difference is smallest when parental involvement takes the form of simply playing with their children.

A December 2005 study by four researchers in the United States and Australia entitled “Scholarly Culture and Educational Success in 27 Nations,” based on twenty years’ worth of data, found that

children growing up in homes with many books get 3 years more schooling than children from bookless homes, independent of their parents’ education, occupation, and class. This is as great an advantage as having university-educated rather than unschooled parents, and twice the advantage of having a professional rather than an unskilled father. It holds equally in rich nations and in poor; in the past and in the present; under Communism, capitalism, and Apartheid; and most strongly in China.

The study went on to say that Chinese children who had five hundred or more books at home got 6.6 years more schooling than Chinese children without books. As few as twenty books in a home made an appreciable difference.

To be sure, there is no substitute for a good teacher. There is nothing more valuable than great classroom instruction. But let’s stop putting the whole burden on teachers. We also need better parents.

Students: We cannot exempt young people themselves, particularly by the time they are in junior or senior high school, from responsibility for understanding the world in which they are living and what it will take to thrive in that world. On November 21, 2010, The New York Times ran a story questioning whether American young people have become too distracted by technology. It contained this anecdote:

Allison Miller, 14, sends and receives 27,000 texts in a month, her fingers clicking at a blistering pace as she carries on as many as seven text conversations at a time. She texts between classes, at the moment soccer practice ends, while being driven to and from school and, often, while studying. But this proficiency comes at a cost: She blames multitasking for the three B’s on her recent progress report. “I’ll be reading a book for homework and I’ll get a text message and pause my reading and put down the book, pick up the phone to reply to the text message, and then 20 minutes later realize, ‘Oh, I forgot to do my homework.’”

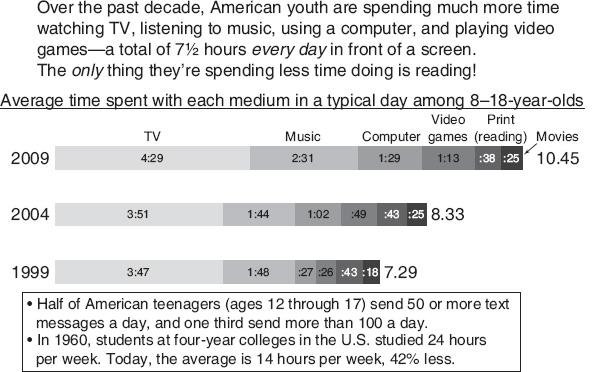

We wish the figure of 27,000 texts a month came out of Ripley’s Believe It Not. In fact, it is the new normal. On January 10, 2010, the Kaiser Family Foundation released the results of a lengthy study entitled Daily Media Use Among Children and Teens Up Dramatically from Five Years Ago:

With technology allowing nearly 24-hour media access as children and teens go about their daily lives, the amount of time young people spend with entertainment media has risen dramatically, especially among minority youth, according to a study released today by the Kaiser Family Foundation. Today, 8–18-year-olds devote an average of 7 hours and 38 minutes (7:38) to using entertainment media across a typical day (more than 53 hours a week). And because they spend so much of that time “media multitasking” (using more than one medium at a time), they actually manage to pack a total of 10 hours and

45 minutes (10:45) worth of media content into those 71/2 hours. The amount of time spent with media increased by an hour and seventeen minutes a day over the past five years, from 6:21 in 2004 to 7:38 today … While the study cannot establish a cause and effect relationship between media use and grades, there are differences between heavy and light media users in this regard. About half (47%) of heavy media users say they usually get fair or poor grades (mostly Cs or lower), compared to about a quarter (23%) of light users … Over the past 5 years, time spent reading books remained steady at about :25 a day, but time with magazines and newspapers dropped (from :14 to :09 for magazines, and from :06 to :03 for newspapers). The proportion of young people who read a newspaper in a typical day dropped from 42% in 1999 to 23% in 2009.

One quote in the study captured the trend: “The amount of time young people spend with electronic media has grown to where it’s even more than a full-time workweek,” said Drew Altman, Ph.D., the president and CEO of the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Source: From The New York Times, January 20, 2010, © 2010 The New York Times. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or transmission of this Content without express written permission is prohibited.

At precisely the moment when we need more education to bring the bottom up to the average and the American average up to the global peaks, our students are spending more time texting and gaming and less time than ever studying and doing homework. Unless we get them to spend the time needed to master a subject, all the teacher training in the world will go for naught.

Business: One of the most unfortunate features of American politics today is that, with a few notable exceptions, the people who know the global labor market best and are most familiar with the skills needed to prosper in it—the members of the business community—have increasingly dropped out of the national debate. Historically, groups such as the Business Roundtable and individual leaders of industry considered it their responsibility to defend, indeed to speak out in favor of, the traditional American formula for greatness. They could be counted upon to go to Washington and lobby, not just on behalf of their own businesses but more broadly for better education, infrastructure, immigration, free trade, and rules to promote constructive risk-taking. That has become less and less true in the last decade. Business leaders are less and less interested in the whole pie and more and more interested in their own slice.

With the merger of globalization and the IT revolution, when American-based multinational firms meet resistance from Washington, D.C., today—arguing in favor of more visas for high-skilled workers, for example—they just move their research facilities abroad or outsource their work to foreign subsidiaries. When Microsoft couldn’t get more visas for high-skilled immigrants to work in its headquarters outside Seattle, Washington, it opened a research center in Vancouver, Canada, 115 miles north. The flatter the world becomes, the less interested the most powerful companies become in fighting with Washington over visas, or almost anything other than their specific tax and antitrust issues. The standard approach of the American business community toward Washington today is, as medieval maps put it, “Here Be Dragons.” You go there, you lobby for your particular tax break, and then you leave—quickly.

The turning point may have come in January 2004, when a consortium of eight leading information-technology company executives, known as the Computer Systems Policy Project, gathered in Washington to lobby Congress against legislation designed to restrict the movement

of jobs overseas, where labor costs are lower. As part of their public outreach, the then CEO of Hewlett-Packard, Carly Fiorina, declared that “there is no job that is America’s God-given right anymore.” At the same time CSPP issued a report explaining that America’s lead in high technology was in serious jeopardy due to competition from other nations.

In an article about the event, the San Francisco Chronicle noted (January 9, 2004) that CSPP offered a long-term proposal to improve grade school and high school education, double federal spending on basic research in the physical sciences, and implement a national policy to promote high-speed broadband communications networks, as Japan and Korea have done. It was exactly the kind of brutally honest intervention from business—here is the world we’re living in and what we need to thrive in it—that we should welcome. Unfortunately, rather than calling for a serious national debate on this broad issue, the subsequent coverage focused almost entirely on Fiorina’s blunt declaration about jobs not being an American right. She got hammered across the country.

One CEO who was at the meeting, but asked not to be identified, told us seven years later that as soon as the words were out of Fiorina’s mouth, he and his colleagues wanted to tiptoe out of the press conference and out of town because they knew the backlash was coming. And come it did. “We have another idea,” the Seattle Post-Intelligencer wrote in a January 9, 2004, editorial that was typical of the backlash. “Why not export a few chief executives’ suites? We’re certain there’s qualified folks somewhere in a far-off land who might run a company for far less than what CEOs are paid in this country.”

Fiorina’s words came back to haunt her six years later, when she ran as a Republican for a Senate seat in California against the incumbent Democrat, Barbara Boxer. Boxer made prominent use in her television commercials of Fiorina’s 2004 declaration and of the job cuts she had made as part of HP’s restructuring during her tenure at the company. It is not a good sign when bluntly speaking the truth turns into a negative political advertisement that harms a candidacy.

While the connection between education and economic growth has never been tighter, we don’t want our young people to be educated just

so that they can be better workers. We want all citizens to be better educated so they can be, well, better citizens. “We want kids to think critically, to read, to create, but not simply because those things will get them jobs and money,” said Susan Engel, the Williams College teaching expert, “but because a society made up of such people will be a better society. People will make more informed decisions, invent things that help the world rather than harm it, and at least some of the time, put the interests of others ahead of self-interest.”

No question: Education should focus on the whole person—should aim to produce better citizens, not just better test takers. About this, Engel is surely right. If our schools teach American children what it means to be an American citizen, they—and America—will have a much better chance of passing on the American formula for greatness to future generations.

But we simply cannot escape the fact that we as a society have some catching up to do in education generally. When you are trying to catch up, you have to work harder, focus on the fundamentals, and get everyone to pitch in. Give us a country where everyone feels that he or she has a real stake in improving education—where parents are focused on their children’s homework, where neighbors care about the quality of their local schools, where politicians demand that their schools be measured against the standards of our peers, where businesses insist that their schools be among the best in the world, and where students understand just how competitive the world is—and we promise you the best teachers will become even be better, the average ones will improve, and the worst ones will truly stick out.