The War on Physics and Other Good Things

Virtually all of America’s energy and climate challenges today can be traced back to one pivotal year and the way life imitated one dramatic film.

The year was 1979, and the film was The China Syndrome.

Set in California’s fictional Ventana nuclear plant, The China Syndrome stars Jane Fonda as a television reporter, Michael Douglas as her cameraman, and Daniel Valdez as her soundman. The movie opens with the three of them being escorted to the observation room at the nuclear reactor to do a feature story on its operations for a local TV station. The room has large soundproof windows that overlook the control room below. Douglas is told not to film but surreptitiously does so anyway. Suddenly there is a panic in the control room. A close-up of a watercooler shows bubbles floating to the top. There is a vibration. “What the hell is that?” asks the shift supervisor, played by Jack Lemmon. An alarm sounds. He taps a gauge, which quickly changes to show the level of coolant to be low. “We have a serious condition!” he says. The panicked staff watches the gauge, as it appears that the reactor core could be exposed. Eventually the coolant levels return to normal and everyone breathes a sigh of relief. In an editing room back at the TV station, Douglas shows his footage to his colleagues. His producer refuses to air it for fear of a lawsuit.

Leaving the station after the evening news, Fonda is told that Douglas has absconded with the film and that she has to get it back. She finds Douglas in a screening room showing the film to a physics professor and a nuclear engineer. The engineer says that it looks as if the reactor’s core

indeed may have come close to exposure. The professor says that that could have led to the “China Syndrome.” “If the nuclear core is exposed,” he says, “the fuel heats up and nothing can stop it. It will melt through the bottom of the plant, theoretically to China. As soon as it hits groundwater, it blasts into the atmosphere and sends out clouds of radioactivity. The number of people killed would depend on which way the wind is blowing.”

The professor then adds ominously, “This would render an area the size of Pennsylvania uninhabitable.”

In the film’s final scenes, Fonda, Douglas, and Lemmon commandeer the control room, locking it from the inside, and begin to broadcast an exposé of the plant’s dangers. Security guards break in and gun down Lemmon. Suddenly the room begins to shake violently. Part of the cooling system begins to crack apart, but the reactor holds. The movie ends with Fonda on live television saying, “I’m convinced that what happened tonight was not the actions of a drunk or a crazy man. Jack Godell [Lemmon] was about to present evidence that he believed would show this plant should be shut down.”

Films often express our unspoken fears. The China Syndrome first appeared in U.S. movie theaters on March 16, 1979. Just twelve days later, on March 28, 1979, the worst nuclear accident in American history took place at Metropolitan Edison’s nuclear power plant—Three Mile Island Unit 2—outside Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

An incorrect reading of equipment at Three Mile Island made the control operators overestimate the amount of coolant covering the plant’s nuclear core. In fact, the coolant was low, leaving half of the reactor’s core exposed. One report estimated that roughly one-third of the core may have reached temperatures as high as 5200 degrees Fahrenheit. Had the situation not been brought under control, the melting fuel core could have cracked open the reactor vessel and containment walls, leading to the China Syndrome. Radiation would have spewed out into the air, and would have done exactly what that professor in the movie warned of—“render an area the size of the state of Pennsylvania permanently uninhabitable.”

As in the movie, Three Mile Island ended without a single person being killed or seriously injured. The releases of radioactive gas and water were inconsequential, and there has been no unusual incidence

of cancer or other diseases for neighborhood residents since then. Three Mile Island’s long-term impact on America’s economic, geopolitical, and environmental health, however, was radioactive in the extreme.

The coincidence of the movie The China Syndrome and the real-life Three Mile Island—and, most important, the steadily soaring costs and legal liabilities of building nuclear power plants that hit in the 1980s—gradually combined to bring a halt to the construction of any new commercial nuclear facilities in America. Unlike solar or wind power or batteries, which get cheaper with each new generation of technology, nuclear power plants have gotten more and more expensive to build. A one-gigawatt nuclear power plant today costs roughly $10 billion to construct and could take six to eight years from start to finish. So what began with fears of runaway reactors and morphed into fears of runaway construction budgets has resulted in this stark fact: It has been more than thirty years since the Nuclear Regulatory Commission has approved construction of a new commercial nuclear power plant in America. The last new nuclear power plant to be completed in America was in 1996—the Watts Bar Nuclear Plant in Tennessee. That plant was approved in 1977.

At the time America abandoned nuclear energy, though, we actually led the world in generating electricity from carbon-free power. Our existing nuclear fleet of 104 reactors now has an average age of thirty years. Just to maintain the current contribution that nuclear power makes to America’s total output of electricity—about 20 percent of national usage—we will need to rebuild or modernize virtually our entire fleet over the next decade. The earthquake and tsunami-triggered Japanese nuclear disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in March 2011—which led to a release of radiation in both the air and water—makes a renewed emphasis on nuclear power in America politically difficult at best and impossible at worst. Because we have not increased the nuclear component of our energy mix for more than thirty years, as our total energy demand grew we came to rely all the more heavily on fossil fuels—coal, crude oil, and natural gas.

The year 1979 proved crucial for energy and the environment for other reasons as well. The cost of oil skyrocketed that year as did oil’s toxic geopolitical consequences. The sequence of events began in January 1979, with the overthrow of the shah of Iran and the subsequent

takeover in Tehran by Ayatollah Khomeini and his followers. Months later, on November 20, 1979, the Grand Mosque in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, was seized by violent Sunni Muslim extremists, who challenged the religious credentials of the Saudi ruling family. After retaking the mosque, the panicked Saudi rulers responded by forging a new bargain with their own Muslim fundamentalists, which went like this: “Let us stay in power and we will give you a free hand in setting social norms, veiling women, curtailing music, restricting relations between the sexes, and imposing religious education. We will go even further and lavish abundant resources on you to spread the austere Sunni Salafi/Wahhabi form of fundamentalism abroad.” This set up a competition between Shiite Iran and Sunni Saudi Arabia to be the leader of the Muslim world, each exporting its puritanical version of Islam. In 1979, “Islam lost its brakes,” said Mamoun Fandy, an Egyptian expert on the Middle East. Mosques and schools all over the Muslim world tilted toward more fundamentalist interpretations of the faith. There was no moderate countertrend, or at least none backed by resources remotely comparable to those of Iran and Saudi Arabia.

As if that weren’t enough for one year, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan on December 24, 1979. In response, Arab and Muslim mujahideen fighters flocked there to drive the Russians out, a jihad financed by Saudi Arabia at America’s behest. In the process, both Pakistan and Afghanistan moved toward a more austere Islamist political orientation. Eventually, the hard-core Muslim fighters in Afghanistan, led by the likes of Osama bin Laden, turned their guns on America and its Arab allies, culminating on September 11, 2001.

Gone were the harmless good old days when our foreign gasoline purchases merely bought villas and yachts on the Riviera for Saudi princes, not to mention gambling sprees in London and Monte Carlo. After the assault on Mecca and the Iranian revolution, our oil addiction started funding madrassas in Pakistan, fundamentalist mosques in Afghanistan and Europe, and Stinger missiles for the Taliban, all of which came back to haunt America in subsequent years. In other words, before 1979 our oil addiction was esthetically distasteful; after 1979 it became geopolitically lethal. We were funding both sides of the war with radical Islam—simultaneously paying for our own military with our tax dollars and indirectly supporting our enemies and their jihadist ideology with our oil dollars.

Hard to believe, but 1979 was just getting started. The energy world would be substantially affected by two other political events of that year. Margaret Thatcher was elected prime minister of Great Britain on May 4, 1979. She and Ronald Reagan, who took office as president of the United States in 1981, implemented free-market-friendly economic policies that helped to pave the way for the expansion of globalization after the fall of the Berlin Wall. This increased economic activity the world over, massively increasing the number of people who could afford cars, motor scooters, electric appliances, and international travel.

Less noticed but just as important, in 1979, three years after Mao Tse-tung’s death, China’s communist government permitted small farmers to raise their own crops on individual plots and to sell the surplus for their own profit. The agricultural reforms had started in the countryside in 1978, but in 1979 capitalism broke out from China’s rural farms into the broader Chinese economy.

In 1979, “the first business license in China was given to Zhang Huamei, a nineteen-year-old daughter of workers in a state umbrella factory who illegally sold trinkets from a table [but] who wanted to conduct her business legally,” according to a historical reconstruction of this era published in The Times of London (December 5, 2009). The Times noted that Zhang is now a dollar millionaire and head of the Huamei Garment Accessory Company, a supplier of many of the world’s buttons. Of her initial sale she said, “The first thing I sold was a toy watch. It was a sunny morning in May 1978. I bought it for 0.15 yuan and sold it for .20. I was very, very excited to make a profit. But I was also very nervous and very afraid the local government staff would come to stop it.” When the government granted her a business license in 1979, the shift of 1.3 billion people from communism to capitalism was on its way. That shift, which produced, among many other things, the conference center in Tianjin with which we began this book, has dramatically increased both global energy demand and the amount of greenhouse gases being pumped into the atmosphere. On January 7, 2010, China’s People’s Daily reported that “a total 16.7 million vehicles were sold in China last year, bringing the country’s total vehicles to more than 186 million,” about half of which are motorcycles. In 1979 virtually no Chinese owned a private car.

One final notable event occurred in 1979. It drew almost no attention. America’s National Academy of Sciences raised its first warning

about something called “global warming.” In a 1979 study, called The Charney Report, the academy stated that “if carbon dioxide continues to increase, [we find] no reason to doubt that climate changes will result and no reason to believe that these changes will be negligible.”

Put all these events together and it becomes clear why 1979 was pivotal in creating today’s energy and climate challenge. The details of that challenge are complicated, and we will discuss some of them in the rest of this chapter. But the key to meeting it is straightforward. The United States must reduce its use of fossil fuels as fast and as far as is prudently possible. We have not begun to do this. All of us are ducking the challenge and some of us are denying that it even exists. This failure could not be more dangerous to our country and our planet, because matters of energy and climate touch on every big issue in American life. That is why we include them as one of the four great challenges the country faces. How we address, or do not address, our energy and climate challenge will affect our economic vitality, our national security, our food supply, and our capacity to benefit from what will be among the biggest industries of the future. Energy policy affects our balance of payments and the value of our currency. It affects the quality of the air we breathe and the level of the oceans on our shores. America will not thrive in the twenty-first century without a different energy policy, one better adapted than the policy we have now to the realities of the flatter world in which we live.

Unfortunately, instead of debating how to generate more clean energy and to slow climate change, we are debating whether to do so. Instead of debating the implications of what is settled science, we are debating the integrity of some scientists. Instead of ending an oil addiction we know is unhealthy for our economy, our air, and our national security, we are begging our pushers for just one more hit from the crude-oil pipe.

While there is much that we don’t know about when and how global warming will affect the climate, and what that will do to weather patterns, to call the whole phenomenon a hoax, to imply that we face no problem at all—that all the scientific evidence for its existence is bogus—is to deny the laws of physics. And while there is also much we do not know about when the earth’s supplies of oil, natural gas, and coal will be exhausted, to behave as if we can consume all we want forever without

staggering financial, environmental, and geopolitical consequences is to deny not only the laws of physics but those of math and economics and geopolitics as well.

Finally, to do all this at once is to mock the market and Mother Nature at the same time. It is to invite each of them to respond violently, suddenly, and at a time of its own choosing.

In February 2010, after a particularly heavy snowfall in Washington, D.C., Oklahoma Republican senator James Inhofe’s daughter, Molly Rapert, her husband, and their four children built an igloo on the Mall near the Capitol in Washington. On one side they stuck a sign that said AL GORE’S NEW HOME. On the other they put one that read HONK IF YOU ♥ GLOBAL WARMING.

We would not have honked.

And neither would 99 percent of the scientists who have studied the problem. This is actually not complicated. We know that global warming is real because it’s what makes life on Earth possible. About this there is no dispute. We have our little planet Earth. It is enveloped in a blanket of naturally occurring greenhouse gases that trap heat and warm the Earth’s surface. Without those gases, our planet’s average temperature would be roughly zero degrees Fahrenheit. About that there is no dispute.

We also know that this concentration of greenhouse gases in the Earth’s atmosphere has been increasing since the Industrial Revolution, because we can actually measure levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. There is no other scientifically plausible explanation for the increase in greenhouse gases than the increased burning of fossil fuels—coal, oil, and natural gas—that began with the Industrial Revolution and surged in the last three decades with the latest stage of globalization. When the Industrial Revolution began, the concentration of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the Earth’s atmosphere was roughly 280 parts per million by volume. By 2011 it was 390 parts per million. About that there is also no dispute.

This naturally had an effect on global average temperatures, which,

again, we can measure. As we thickened the blanket of greenhouse gases around the Earth, it trapped more of the sun’s rays and the heat that they generated. As the Earth Policy Institute, a nonpartisan research center dedicated to tracking climate change, notes in its report for 2010:

The earth’s temperature is not only rising, it is rising at an increasing rate. From 1880 through 1970, the global average temperature increased roughly 0.03 degrees Celsius each decade. Since 1970, that pace has increased dramatically, to 0.13 degrees Celsius per decade. Two thirds of the increase of nearly 0.8 degrees Celsius (1.4 degrees Fahrenheit) in the global temperature since the 1880s has occurred in the last forty years. And nine of the ten warmest years happened in the last decade.

The EPI report explains that global average temperature is influenced—up and down—by a number of factors besides carbon emissions, including various naturally occurring cycles involving the sun and atmospheric winds. But the current natural cycles should be causing global average temperatures to go down, not up. The recorded rise in global temperatures is therefore doubly worrying.

The EPI report concludes as follows: “Topping off the warmest decade in history, 2010 experienced a global average temperature of 14.63 degrees Celsius (58.3 degrees Fahrenheit), tying 2005 as the hottest year in 131 years of recordkeeping.” In addition, “while 19 countries recorded record highs in 2010, not one witnessed a record low temperature … Over the last decade, record highs in the United States were more than twice as common as record lows, whereas half a century ago there was a roughly equal probability of experiencing either of these.”

As the Earth’s greenhouse blanket traps more heat and raises global average temperatures, it melts more ice. According to the EPI, 87 percent of marine glaciers on the Antarctic Peninsula have retreated since the 1940s. There is enough water frozen in Greenland and Antarctica to raise global sea levels by more than 230 feet if they were to melt entirely.

These are facts about which there can be no dispute. They all can be measured.

While no single weather event can be attributed directly to climate change, the large number of extreme weather events of 2010 are all

characteristic of what scientists expect from a steadily warming climate. Climate change, they argue, will make the wets wetter, the snows heavier, and the dries drier, because warmer air holds more water vapor and that extra moisture leads to heavier storms in some areas and even less rainfall in others. The record events in 2010 included floods in Australia and Pakistan, a heat wave in Russia that claimed thousands of lives, unprecedented forest fires in Israel, landslides in China, record snowfall across the mid-Atlantic region of the United States, and twelve Atlantic Ocean hurricanes. That is why we believe the term “global weirding,” coined by L. Hunter Lovins, a co-founder of the Rocky Mountain Institute, is a more accurate way to describe the climate system into which the world is moving than is “global warming.” Global warming … It sounds so cuddly. It will be anything but that.

Beyond these well-established core facts lie many uncertainties. We do not know how hot the world will become or how rapidly it will warm. This is so not only because we cannot forecast precisely how much greenhouse gas the planet’s 6.8 billion humans will produce but also because, as many climate scientists believe, the Earth’s temperature may well rise at a rate even higher than greenhouse gas emission alone would cause, through what are called “feedback effects.” Higher temperatures, for example, could melt the tundra found in the world’s northern latitudes (this has already begun), releasing the potent greenhouse gas methane, which lies beneath it, and thereby thickening the heat-trapping blanket that surrounds the Earth. Nor can we be sure what the consequences of higher temperatures will be for the planet. The Earth’s atmosphere and its surface are complicated interrelated systems, too complicated to lend themselves to precise prediction even by the best scientists using the most sophisticated mathematical models. The social and political effects of the geophysical consequences of higher global temperatures involve even greater uncertainties. They could include famines, mass migrations, the collapse of governmental structures, and wars in the places most severely affected. Unfortunately, it is not possible to know in advance how, whether, and when global warming will trigger any or all of these things.

So, yes, there are uncertainties surrounding the effects of climate change, but none about whether it is real. The uncertainties concern how and when its effects will unfold. Moreover, one thing that usually

gets lost in the debate about these uncertainties is the fact that uncertainty cuts both ways. True, the consequences of the ongoing increase in the global temperature could turn out to be more benign than the forecasts of most climate scientists. Let’s hope that they do. But they could also turn out to be worse—much worse.

You would not know that, though, from reading the newspapers in 2010. Climate skeptics, many funded by the fossil-fuel industries, seized on a few leaked e-mails among climate scientists working with Great Britain’s University of East Anglia’s Climatic Research Unit to gin up a controversy about the conduct of some of its scientific investigators. Whatever one thinks of this specific case, it hardly invalidates the scientific consensus on global warming based on independent research conducted all over the world, nor do a few minor mistakes in the UN’s massive Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report. But for a public too busy to take the time to study these issues, without the background to appreciate fully how little these errors touched on the larger scientific certainties and disinclined to ask why and how climate scientists all over the world could organize a vast conspiracy to get people to believe this problem was more serious than it is, these news stories created doubt and confusion about the issue and helped to stall any U.S. climate legislation.

The climate skeptics took a page right out of the tobacco industry’s book, said Joseph Romm, the physicist and popular Climateprogress.org blogger. “When the whole smoking-causes-cancer issue came up, the tobacco industry figured out that it did not have to win the debate, it just had to sow enough doubt to pollute what people thought. It was: ‘I don’t have to convince you that I am right. I just have to convince you that the other guy may be wrong.’ The tobacco people wrote a famous memo that said ‘Doubt is our product.’ It is a much easier threshold to meet.” The other thing the skeptics have on their side is that their goal is to persuade you that the way you are living your life is just fine. It is human nature to “remember and latch on to things that confirm your worldview and ignore and discount those things that don’t. It is called ‘confirmation bias,’” said Romm.

At the same time, scientists, who tend to focus on what they don’t know more than on what they do, also tend to be poor communicators and defenders of their positions. As Romm put it: “Scientists do live in ivory towers. They believe that facts win debates and speak for themselves

and that you don’t need to market your ideas or repeat them over and over again. And they are even distrustful of people who repeat themselves or cultivate too high a public profile.”

Eventually, though, the irresponsible campaign against the science of climate change reached the point that it triggered an open letter signed by 255 members of America’s National Academy of Sciences, the nation’s top scientific society, which was published in Science magazine on May 7, 2010. Here is what the scientists said:

All citizens should understand some basic scientific facts. There is always some uncertainty associated with scientific conclusions; science never absolutely proves anything. When someone says that society should wait until scientists are absolutely certain before taking any action, it is the same as saying society should never take action. For a problem as potentially catastrophic as climate change, taking no action poses a dangerous risk for our planet.

Scientific conclusions derive from an understanding of basic laws supported by laboratory experiments, observations of nature and mathematical and computer modeling. Like all human beings, scientists make mistakes, but the scientific process is designed to find and correct them. This process is inherently adversarial—scientists build reputations and gain recognition not only for supporting conventional wisdom, but even more so for demonstrating that the scientific consensus is wrong and that there is a better explanation. That’s what Galileo, Pasteur, Darwin, and Einstein did. But when some conclusions have been thoroughly and deeply tested, questioned, and examined, they gain the status of “well-established theories” and are often spoken of as “facts.”

The letter went on to list the fundamental, well-established scientific conclusions about climate change:

(i) The planet is warming due to increased concentrations of heat-trapping gases in our atmosphere. A snowy winter in Washington does not alter this fact. (ii) Most of the increase in the concentration of these gases over the last century is due to

human activities, especially the burning of fossil fuels and deforestation. (iii) Natural causes always play a role in changing Earth’s climate, but are now being overwhelmed by human-induced changes. (iv) Warming the planet will cause many other climatic patterns to change at speeds unprecedented in modern times, including increasing rates of sea-level rise and alterations in the hydrologic cycle. Rising concentrations of carbon dioxide are making the oceans more acidic. (v) The combination of these complex climate changes threatens coastal communities and cities, our food and water supplies, marine and freshwater ecosystems, forests, high mountain environments, and far more.

The conclusion that emerges from the summary is that while climate change does involve substantial uncertainties, they concern when and how, not whether, it will affect the planet. Sigma Xi, the Scientific Research Society, concluded in its February 2007 report for the United Nations that the only sensible response now to the reality of global warming is a two-pronged action strategy to “avoid the unmanageable (mitigation) and manage the unavoidable (adaptation)”—because some significant climate change is coming, even if we don’t know when or how much damage it will do.

In other words, uncertainty is a reason to act and not a reason not to act. After all, people in Kansas buy insurance on their homes not because they are certain that a tornado will smash it one day but because they cannot be sure one will not. When faced with a credible threat with potentially catastrophic consequences, uncertainty is why you act—especially with this climate problem, because buying energy and climate insurance will not only pay for itself, it will eventually make a profit. For both these reasons, we favor the “Dick Cheney Strategy” when dealing with the climate issue.

Why do we call it that? In 2006, Ron Suskind published The One Percent Doctrine, a book about the U.S. war on terrorists after 9/11. The title came from an assessment by then vice president Dick Cheney, who,

in the face of concerns that a Pakistani scientist was offering nuclear-weapons expertise to al-Qaeda, reportedly declared: “If there’s a 1% chance that Pakistani scientists are helping Al Qaeda build or develop a nuclear weapon, we have to treat it as a certainty in terms of our response.” Cheney contended that the United States had to confront a very new type of threat: a “low-probability, high-impact event.”

Soon after Suskind’s book was published, the legal scholar Cass Sunstein, then at the University of Chicago, pointed out that Cheney seemed to be endorsing the same “precautionary principle” that animated environmentalists. Sunstein wrote in his blog: “According to the Precautionary Principle, it is appropriate to respond aggressively to low-probability, high-impact events—such as climate change. Indeed, another vice president—Al Gore—can be understood to be arguing for a precautionary principle for climate change (though he believes that the chance of disaster is well over 1 percent).”

Cheney’s instinct on nuclear weapons in the hands of rogue states is the right framework for thinking about the climate issue. It’s all a game of odds. We’ve never been here before, but we do know two things. First, the CO2 we put into the atmosphere stays there for several thousand years, so it is “irreversible” in real time (barring some not-yet-invented technique of geo-engineering to extract greenhouses gases from the atmosphere). And second, the CO2 buildup, if it reaches a certain point, has the potential to unleash “catastrophic” global warming—warming at a level that no humans have ever experienced. We do not know for sure (and cannot know until it is too late) that this will happen, but we do know that it could happen. Since the buildup of greenhouse gases is irreversible and the impact of that buildup could be “catastrophic”—that is, it could create such severe and irreparable damage to the Earth’s ecosystem that it would overturn the normal patterns of human life on the planet—the sensible, prudent, conservative thing to do is to buy insurance.

This is especially advisable when there is every chance our response will eventually turn a profit and serve as an antidote to almost every energy /climate problem set in motion in 1979. If we prepare for climate change by gradually building an economy based on clean-power systems but climate change turns out not to be as damaging as we expect, what would be the result? During a transition period, we would have

higher energy prices, while new technologies providing both clean power and greater efficiency achieved scale from mass production. Very quickly, though, we would have higher energy prices but lower energy bills, as well as lower greenhouse gas emissions, as the new technologies dramatically improved efficiency to give us more power from less energy for less money. In its 2009 report Unlocking Energy Efficiency in the U.S. Economy, the McKinsey consultancy found that if serious but affordable energy-efficiency measures were implemented throughout the U.S. economy through 2020, this would yield gross energy savings worth more than $1.2 trillion—more than twice the $520 billion investment in such measures needed in that time frame. Energy efficiency, that is, would save more than twice as much as it would cost.

At the same time, as a result of buying insurance by starting the transition to clean energy, we would become competitive in what is sure to become the next great global industry. Even if global warming did not exist at all, the fact that the planet is on track to move from 6.8 billion people today to 9.2 billion by 2050, and more and more of these people will indeed live in American-size homes, drive American-size cars, and eat American-size Big Macs, means that global energy demand for oil, coal, and gas will surge. Fossil fuels will therefore become more expensive, and the pollution they cause will increase. This will raise the demand for clean, renewable energy, and rising demand will stimulate an increasing supply. There is every reason to believe, in other words, that clean energy will become the successor to information technology as the next major cutting-edge industry on which the economic fortunes of the richest countries in the world will depend. That is the bet that China has made in its twelfth five-year plan, authorized in March 2011, which stresses that development of renewable energy will be the key to China’s energy security for the next decade. That plan places special emphasis on developing solar and nuclear energy.

Moreover, renewable energy depends on new technology, which the United States has historically led the world in developing. China is now seeking to seize that position. “Chinese solar panel manufacturers accounted for slightly over half the world’s production last year,” Keith Bradsher, the New York Times Hong Kong business reporter, wrote (January 14, 2011). “Their share of the American market has grown nearly sixfold in the last two years, to 23 percent in 2010, and is still rising

fast … In addition to solar energy, China just passed the United States as the world’s largest builder and installer of wind turbines.” Bradsher also noted that since 2007, China has become the world’s leading builder of more efficient, less polluting coal power plants, mastering the technology and driving down the cost. “While the United States is still debating whether to build a more efficient kind of coal-fired power plant that uses extremely hot steam, China has begun building such plants at a rate of one a month,” Bradsher wrote (May 10, 2009). China is also building far more nuclear power plants than the rest of the world combined.

America does not have in place the rules, standards, regulations, and price signals—the market ecosystem—to stimulate thousands of green innovators in thousands of green garages to devise the breakthrough technologies that will give us multiple sources of abundant, cheap, reliable, carbon-free energy. Solar “is an industry we pioneered and invented,” explained Phyllis Cuttino, the director of the Pew Charitable Trusts’ Clean Energy Program. “We used to be the leading manufacturer of solar in the world, and now the largest manufacturers of solar and wind are China and Germany. In 2008, we led the world in private investment and financing of clean energy. In 2009 China took the lead at $54 billion, Germany is attracting $41 billion, and we are at $34 billion.”

A key reason for the rise of Germany and China in clean power, Cuttino noted, is that they both used “domestic policy tools to create huge internal demand.” If we set high energy-efficiency standards for our own buildings, trucks, cars, and power plants, we would trigger innovation by American companies, which would then be better positioned to compete globally. If, on the other hand, we lower those standards, we invite competition from low-cost, low-standards competitors.

Beyond the potential for spawning new industries, taking climate change and our oil addiction seriously would surely bring strategic advantages. Led by Ray Mabus, President Obama’s secretary of the navy and the former U.S. ambassador to Saudi Arabia, the navy and marines are not waiting. Using their own resources, they have been building a strategy for “out-greening” al-Qaeda, the Taliban, and the world’s petro-dictators. Their efforts derive from a Pentagon study from 2007 data that found that the U.S. military suffers one person killed or wounded for

every twenty-four fuel and water convoys it runs in Afghanistan. Today, many hundreds of these convoys are needed each month to transport the fuel to run air conditioners and to power diesel generators—to remote bases all over Afghanistan.

On April 22, 2010, Earth Day, the navy flew an F/A-18 Super Hornet fighter jet powered by a fifty-fifty blend of conventional jet fuel and camelina aviation biofuel made from pressed mustard seeds. That fighter jet flew at Mach 1.2 (850 miles per hour) and has since been tested on biofuels at Mach 1.7 (nearly 1,300 miles per hour)—without a hiccup. As Scott Johnson, general manager of Sustainable Oils, which produced the camelina, put it in Biofuels Digest: “It was awesome to watch camelina biofuel break the sound barrier.”

Mabus believes that if the navy and marines could deploy generators in Iraq and Afghanistan with renewable power, as well as more energy-efficient tents; could run more ships on nuclear energy, biofuels, and hybrid engines; and could fly some of its jets with biofuels, it would gain a major advantage over the Taliban and America’s other adversaries. This is still a long, long way off, but it is heartening to see the Pentagon taking some leadership on this issue—which is no surprise, since for the marines it is a life-and-death issue. The best way to avoid a roadside bomb is not to have vehicles on the roads trucking fuel in the first place. Similarly, the best way not to have to kowtow to petro-dictators is to take away, or reduce the value of, the only source of income they have. And the best way to make it possible for the United States to cut its military budget without harming the nation’s security is to reduce our and the world’s addiction to oil. Making oil less important would reduce the military forces we have to keep on station to protect its flow from the Persian Gulf to the rest of the world. And, of course, importing less oil would strengthen the dollar. Americans currently send more than $1 billion a day abroad to purchase both crude oil and refined petroleum products from around the world. Bring that number down with energy efficiency and clean power, and America’s trade deficit would improve. As a bonus, the air we breathe would be cleaner, so our health-care bills would be lower.

Any of these points individually would argue for adopting a different policy on energy and climate. All of them together add up to a case that is overwhelming. No single measure would do more to make America stronger, wealthier, more innovative, more secure, and more respected

than implementing a sound energy strategy—putting a price on carbon, or increasing the gasoline tax, or establishing national energy-efficiency standards for every building and home. To dismiss global warming as a hoax and refuse to take any of these steps to reduce our addiction to oil, therefore, is to wage war not just against physics but against the American national interest and against elementary prudence.

China has a different approach. “There is really no debate about climate change in China,” said Peggy Liu, chairwoman of the Joint U.S.-China Collaboration on Clean Energy, a nonprofit group working to accelerate the greening of China. “China’s leaders are mostly engineers and scientists, so they don’t waste time questioning scientific data.” Air pollution is much worse in China than in the United States because the country burns huge quantities of cheap coal. That creates serious health problems of a kind that, fortunately, we in the United States do not face. For this reason, Liu added, the push to be green in China “is a practical discussion on health and wealth. There is no need to emphasize future consequences when people already see, eat, and breathe pollution every day.” And because runaway pollution in China means wasted lives, air, water, ecosystems, and money—and wasted money means fewer jobs and more political instability—the regime takes it seriously. Energy efficiency achieves three goals at once for China. The country saves money, takes the lead in the next great global industry, and earns some credit with the world for mitigating climate change.

Why is that attitude so hard for America to duplicate? Why has the United States failed so abjectly to meet the related challenges of climate change and energy?

For starters, climate change occurs gradually and may not produce an equivalent of Pearl Harbor—until it is too late. That is, it’s another one of those slowly unfolding problems—like the deficit—in which there is a fundamental mismatch between the cause and the people who cause it, on the one hand, and the effect and the people who will be most affected, on the other. The effects lag far behind the causes.

So, for example, whatever global warming effects we’re experiencing today, which are relatively mild, are the product of CO2 emissions from

decades ago, before China and India and Brazil became economic powerhouses. And the emissions that we are pouring into the atmosphere today will be felt by our grandchildren in 2050. When people cannot see any immediate effect of what scientists tell them is harmful behavior, generating collective action to stop that behavior is extremely difficult. But this also means that if and when the environmental equivalent of Pearl Harbor does come, the response will have to be sweeping and disruptive.

“Time here is indeed the enemy,” said Hal Harvey, the former CEO of the ClimateWorks Foundation and now an independent energy expert. “Things that happen suddenly, like a pinprick or a tornado, capture our attention. But we don’t even notice things that unfold over years or decades.”

Another reason we keep putting off action on global warming is that the solution requires putting a price on carbon and setting stronger energy-efficiency standards. Since politicians don’t want to propose either of those, they prefer not to talk about the problem. This did not use to be us. Under the leadership of presidents Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter, the United States reacted to the 1973–1974 Arab oil embargo by putting in place higher fuel-economy standards for cars and trucks. In 1975, Congress, with broad bipartisan support, passed the Energy Policy and Conservation Act, which established corporate average fuel economy standards that required the gradual doubling of efficiency for new passenger vehicles—to 27.5 miles per gallon—within ten years. As a result of that, said Amory Lovins of the Rocky Mountain Institute, “we raised our oil productivity 5.2 percent a year for eight years from 1977 through 1985; oil imports fell 50 percent and oil imports from the Persian Gulf fell 87 percent. We broke OPEC’s pricing power for a decade by cutting their sales in half.” Oil tumbled in price to below $15 a barrel. “Just think,” added Lovins, “with today’s innovations, we could rerun that old play so much better, and imagine what the impact would be.”

It was a Republican president, Richard Nixon, who signed into law the first pieces of major environmental legislation in the United States, which addressed our first generation of environmental problems—air pollution, water pollution, and toxic waste. In particular, Nixon pushed Congress to pass the landmark Clean Air Act of 1970, and to oversee environmental protection, he also created both the Department of Natural Resources and the Environmental Protection Agency.

It was Ronald Reagan’s secretary of state, George Shultz, who oversaw the negotiation of the Montreal Protocol on Substances That Deplete the Ozone Layer—a landmark international agreement designed to protect the stratospheric ozone layer that shields the planet from damaging UVB radiation. And it was President George H. W. Bush who introduced the idea of “cap and trade” to address an environmental problem. Yes, you read that correctly.

In an article entitled “The Political History of Cap and Trade,” published in Smithsonian magazine (August 2009), Richard Conniff details the story of how “an unlikely mix of environmentalists and free-market conservatives hammered out the strategy known as cap-and-trade.” As Conniff explained it,

The basic premise of cap-and-trade is that government doesn’t tell polluters how to clean up their act. Instead, it simply imposes a cap on emissions. Each company starts the year with a certain number of tons allowed—a so-called right to pollute. The company decides how to use its allowance; it might restrict output, or switch to a cleaner fuel, or buy a scrubber to cut emissions. If it doesn’t use up its allowance, it might then sell what it no longer needs. Then again, it might have to buy extra allowances on the open market. Each year, the cap ratchets down, and the shrinking pool of allowances gets costlier …

Getting all this to work in the real world required a leap of faith. The opportunity came with the 1988 election of George H. W. Bush. [Environmental Defense Fund president] Fred Krupp phoned Bush’s new White House counsel [C. Boyden Gray] and suggested that the best way for Bush to make good on his pledge to become the “environmental president” was to fix the acid rain problem, and the best way to do that was by using the new tool of emissions trading. Gray liked the marketplace approach, and even before the Reagan administration expired, he put EDF staffers to work drafting legislation to make it happen …

John Sununu, the White House chief of staff, was furious. He said the cap “was going to shut the economy down,” Boyden Gray recalls. But the in-house debate “went very, very fast. We didn’t have time to fool around with it.” President Bush not only

accepted the cap, he overruled his advisers’ recommendation of an eight million-ton cut in annual acid rain emissions in favor of the ten million-ton cut advocated by environmentalists …

Almost 20 years since the signing of the Clean Air Act of 1990, the cap-and-trade system continues to let polluters figure out the least expensive way to reduce their acid rain emissions.

Alas, today’s Republican Party is different. An October 2010 poll by the Pew Research Center for the People & the Press found that a “53%-majority of Republicans say there is no solid evidence the earth is warming. Among Tea Party Republicans, fully 70% say there is no evidence. Disbelief in global warming in the GOP is a recent occurrence. Just a few years ago, in 2007, a 62%-majority of Republicans said there is solid evidence of global warming, while less than a third (31%) said there is no solid evidence.”

Not all Republicans are happy about this. As Sherwood Boehlert, a Republican who represented New York’s Twenty-fourth District in Congress from 1983 to 2007, put it in The Washington Post (November 19, 2010),

I call on my fellow Republicans to open their minds to rethinking what has largely become our party’s line: denying that climate change and global warming are occurring and that they are largely due to human activities. The National Journal reported last month that 19 of the 20 serious GOP Senate challengers declared that the science of climate change is either inconclusive or flat-out wrong. Many newly elected Republican House members take that position. It is a stance that defies the findings of our country’s National Academy of Sciences, national scientific academies from around the world and 97 percent of the world’s climate scientists … There is a natural aversion to more government regulation. But that should be included in the debate about how to respond to climate change, not as an excuse to deny the problem’s existence … My fellow Republicans should understand that wholesale, ideologically based or special-interest-driven rejection of science is bad policy. And that in the long run, it’s also bad politics. What is happening

to the party of Ronald Reagan? He embraced scientific understanding of the environment and pollution and was proud of his role in helping to phase out ozone-depleting chemicals. That was smart policy and smart politics.

There is another new factor blocking legislative action against climate change: the shift in Senate rules whereby it now requires sixty votes to shut off a filibuster and thereby pass any significant legislation such as an overhaul of our energy system. A significant majority of Democratic senators were ready to pass such legislation, the Waxman-Markey cap-and-trade bill, in President Obama’s first two years, but even though the Democrats had a sixty-vote majority, they could only muster from fifty to fifty-two votes, because oil-state and coal-state Democrats could not be brought on board. Surely, however, they could have found ten Republicans who would support such legislation or offer their own simpler alternative to cap and trade, such as a carbon tax, could they not?

After all, as Senator Lindsey Graham of South Carolina told Tom in an interview in February 2007, when this legislation was being debated, it was vital for the country and his party to help produce some clean-energy legislation. “I have been to enough college campuses to know if you are thirty or younger this climate issue is not a debate,” said Graham. “It’s a value. These young people grew up with recycling and a sensitivity to the environment—and the world will be better off for it. They are not brainwashed … From a Republican point of view, we should buy into it and embrace it and not belittle them. You can have a genuine debate about the science of climate change, but when you say that those who believe it are buying a hoax and are wacky people, you are putting at risk your party’s future with younger people.”

Graham’s approach to bringing around the conservative state he represents was to avoid talking about “climate change.” Instead, he framed America’s energy challenge as a need to “clean up carbon pollution,” to “become energy independent,” and to “create more good jobs and new industries for South Carolinians.” He proposed “putting a price on carbon,” starting with a focused carbon tax rather than an economy-wide cap-and-trade system, so as to spur both consumers and industries to invest in and buy new clean-energy products. He included nuclear energy, and insisted on permitting more offshore drilling for oil and gas

to provide more domestic sources as we make the long transition to a new clean-energy economy.

“You will never have energy independence without pricing carbon,” Graham argued. “The technology doesn’t make sense until you price carbon. Nuclear power is a bet on cleaner air. Wind and solar is a bet on cleaner air. You make those bets assuming that cleaning the air will become more profitable than leaving the air dirty, and the only way it will be so is if the government puts some sticks on the table, not just carrots. The future economy of America and the jobs of the future are going to be tied to cleaning up the air, and in the process of cleaning up the air this country becomes energy independent and our national security is greatly enhanced.” Remember, he added, “we are more dependent on foreign oil today than after 9/11. That is political malpractice, and every member of Congress is responsible.”

We have no problem with this more conservative approach. Unfortunately, Graham could not get a single Republican senator to join him when he worked out a draft bill—with senators Joseph Lieberman and John Kerry—that included a complex mechanism for pricing carbon, which was never called a tax but was tantamount to it. As The New Yorker’s Ryan Lizza noted in a reconstruction of the failure by the Senate to produce an energy bill (October 11, 2010), Republican senators looking to follow Graham’s lead were bombarded with allegations that they were raising taxes and killing jobs. As a result, each and every one of them backed off, including Graham. A lot of this had to do with intra-Republican politics. Lizza reported, “Graham warned Lieberman and Kerry that they needed to get as far as they could in negotiating the bill ‘before Fox News got wind of the fact that this was a serious process,’ one of the people involved in the negotiations said. ‘He would say: The second [the Fox newscasters] focus on us, it’s gonna be all cap-and-tax all the time, and it’s gonna become just a disaster for me on the airwaves. We have to move this along as quickly as possible.’” Unfortunately, they couldn’t. Fox found out, Graham backed off, and the bill died.

In addition, the vested interests in the oil, coal, and gas industries, and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, spread their political donations around to make sure that nothing happened. As Lizza noted, “Newt Gingrich’s group, American Solutions, whose largest donors include coal and electric-utility interests, began targeting Graham with a flurry of online articles about the ‘Kerry-Graham-Lieberman gas tax bill.’”

In the middle of all this, President Obama decided that he would not spend any significant political capital to press for the clean-energy legislation, to set a price on carbon, or to refute aggressively the climate-change deniers. His political advisers told him it would not be good politics heading into the 2012 election. Rather than change the polls, the president chose to read the polls.

So 2010 turned out to be a microcosm of all the forces undermining our ability to get something big, or even something small, done to deal with our energy and climate challenges. The Democrats were cowardly, and the Republicans were crazy. The Democrats understood the world they were living in but did not want to pay the political price—alone—for adapting to it. The Republicans simply denied the reality of this world. Democrats didn’t have the courage of their convictions. Republicans had the wrong convictions. In the end, both parties acted as if a serious energy and climate policy is a luxury that can be put off indefinitely or achieved simply with investments and incentives but without a price signal.

By the end of 2010, the energy debate shifted to the prospect of abundant domestic natural gas. Recently, new exploration and drilling technologies have made vast new gas reserves economically attractive. Because of this, America’s recoverable gas reserves have grown ten- to twentyfold in just the last few years. The United States is producing so much natural gas that, whereas the government warned four years ago of a critical need to boost imports, it is now considering approving an export terminal. This sounds great—and it might be—but it could equally portend real trouble if not put in the proper context. If we just opt for one more fix of cheap hydrocarbons, consuming them as fast as we can, this bonanza will simply extend our energy and climate denial, make things worse, and miss the next great global industry. If we choose to use gas as an intelligent bridge to a clean-energy future, it can make the transition easier and speedier. Where possible, we should use gas to shut down our oldest, dirtiest coal power plants as rapidly as we can. After all, generating a kilowatt hour of electricity with a natural gas turbine emits only about half as much carbon dioxide as a coal plant would emit. But to exploit our new reserves of natural gas, which are embedded in deep formations, special drilling techniques known as “fracking” are required, and these can be environmentally destructive. The natural gas industry and the environmental community need to work together to

develop guidelines to determine where drilling for natural gas can safely take place and how to avoid contaminating aquifers. Fracking can be done properly, says Hal Harvey: “The oil and gas companies need to decide: Do they want to fight a bloody and painful war of attrition with local communities or take the lead in setting high environmental standards and then live up to them?” Harvey offers five basic rules for fracking: don’t allow leaky systems; use gas to phase out coal; have sound well drilling and casing standards; don’t pollute the landscape with brackish or toxic water brought up by fracking; and drill only where it is sensible. Higher environmental standards may cost more, but only incrementally, if at all, and they’ll make the industry and the environment safer.

We began this chapter by recounting the events of 1979 that fed off one another to create a giant feedback loop that has fueled the energy and climate challenge faced by America and the world ever since. A similarly toxic feedback loop, or vicious cycle, appeared in 2010. Unless we create a virtuous cycle to counter it, it will wreak even greater havoc.

Here is what we mean: The UN Food and Agriculture Organization tracks the global prices of fifty-five food commodities. In December 2010, the FAO Food Price Index hit its highest level since records began being kept in 1990, climbing above the peak reached during the 2008 food crisis. Those rising food prices were one factor, perhaps the last straw, that sparked the political uprising in Tunisia, which quickly spread to Egypt, Libya, Bahrain, Syria, Yemen, and across the Arab world. Those uprisings then triggered disruptions in oil production and speculations in oil futures, sending global oil prices soaring toward their historic peaks. Higher oil prices, in turn, raised food costs, because of oil’s prominence in fertilizers, food production, and transportation. So the prices for rice, corn, potatoes, and other staples that sustain the world’s poor all spiked. Rice alone is a basic food for three billion of the world’s people. The continually rising food prices heightened discontent in the Arab world (and elsewhere), which kept pressure on oil prices, which kept pressure on food prices, and so on …

This inner loop is being reinforced by another loop of steadily rising world population, plus steadily rising standards of living, plus steadily rising climate change. Egypt alone has grown from twenty-two million people in 1950 to eighty-two million today. That is one reason that FAO experts estimate that global food production will have to increase by some 70 percent by 2050 to keep up with the world’s population growth from 6.8 billion to 9.2 billion. Meanwhile, thanks to the hyper-connecting of the world, more and more people will be living, driving, and eating like Americans, increasing the demand for fossil fuels, which will put even more stress on global natural resources and oil prices. China faces major water shortages already, with industrial demand for water roughly doubling every seven to eight years. Yemen may be the first country in the world actually to run out of water.

Some of the world’s leading investors believe this is the start of a major global shift in resource supply and demand. “Accelerated demand from developing countries, especially China, has caused an unprecedented shift in the price structure of resources: after 100 years or more of price declines, they are now rising, and in the last 8 years have undone, remarkably, the effects of the last 100-year decline,” the noted money manager Jeremy Grantham wrote in his April 2011 report to investors. “Statistically, also, the level of price rises makes it extremely unlikely that the old trend is still in place … From now on, price pressure and shortages of resources will be a permanent feature of our lives. This will increasingly slow down the growth rate of the developed and developing world and put a severe burden on poor countries. We all need to develop serious resource plans, particularly energy policies. There is little time to waste.”

All these trends are being exacerbated by the fact that the more people there are on the planet, the more urbanized the world becomes. Urbanization increases global warming, which, as we have noted, many scientists predict will set off even more severe storms, droughts, deforestation, and floods of the kind that ruined harvests all over the world in 2010. The more that harvests are disrupted, the higher food prices will rise. The higher food prices rise, the more political uprisings there will be. The more uprisings, the higher fuel prices will rise. Welcome to our own 1979-like feedback loop in 2011. The only way to stop it is for America, and other big industrialized countries, to launch a virtuous cycle to counter this emerging vicious one.

“We need to bring our own cause-and-effect logic” to this dangerous

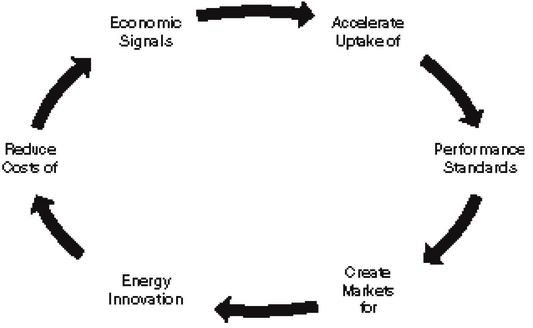

feedback loop gathering momentum today, argues Hal Harvey. He proposes an approach with three parts: performance standards, a price on carbon, and research and innovation. Melded together, they can create a powerful virtuous cycle.

Twenty years’ experience in California demonstrates the gains in efficiency and innovation that can come from steadily rising performance standards. California’s strategy reduced electricity consumption in refrigerators by a full 80 percent. New houses, built with ever higher performance standards, known as building codes, have cut energy use in new homes there by 75 percent compared to precode versions. Together, these policies now save the average California family some $1,000 per year. The state is going further: It has led the nation in raising mileage standards for cars and trucks, and in raising requirements for utilities to provide energy produced from solar, wind, hydro, or nuclear sources. These performance standards are transforming the California energy economy.

As technology improves, performance standards need to advance as well. As noted earlier, in 1974, in the wake of the Arab oil embargo, Congress doubled the average efficiency standard for new automobiles sold in the United States, from about thirteen miles per gallon to more than twenty-five, over the next decade. Unfortunately, “this improvement, designed as a floor, turned into a de facto cap on fuel economy for most manufacturers, and fuel economy remained stuck for two decades,” said Harvey. One reason was that Detroit fiercely—and, as it turns out, suicidally—fought any change in the standards the whole time. “Imagine if, instead, the fuel economy level had grown just 2 percent per year after 1985,” said Harvey. “U.S. cars would have reached an average of forty-four miles per gallon this year, Detroit would be a technology leader, U.S. oil consumption would be three million barrels per day less.” We would have saved hundreds of millions of dollars, and the recent oil shocks would have been avoided or been far less severe.

It is never too late to get this right, because the gains are so huge and the costs so low. Fortunately, the Obama administration has taken steps in the right direction. In November 2011, Obama’s Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Department of Transportation (DOT) struck a deal with all the top U.S.-based automakers that will go into effect in 2017 and require annual mileage improvements of 5 percent for cars, and a little less for light trucks and SUVs, until 2025—when U.S. automakers

will have to reach a total fleet average of 54.5 miles per gallon. The current average is 27.5 miles per gallon. This deal will help America’s cars and trucks approach the mileage levels that prevail in Europe and Japan, and will spur innovation in power trains, aerodynamics, batteries, and electric cars—and in steel and aluminum that will make cars lighter and safer. The EPA and the DOT estimate that these new innovations will gradually add about $2,000 to the cost of an average vehicle by 2025 and will save more than $6,000 in gasoline purchases over the life of that car—savings that will go into the rest of the economy. And all that assumes that gasoline prices will only moderately increase and there are no innovation breakthroughs beyond what we anticipate. If gasoline prices soar and innovation goes faster—both highly likely—the savings would be even greater. The new vehicles sold over the life of the program—including its first phase between 2012 and 2016—are expected to save a total of four billion barrels of oil and prevent two billion metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions. (There are some loopholes that the auto industry could exploit that would lower those figures, but the improvements should still be significant.)

The compromise worked out between the EPA and the DOT with General Motors, Ford, Fiat SpA affiliate Chrysler Group, Toyota, Honda, Nissan, BMW, and six other car companies came about because once the Supreme Court ruled that carbon dioxide was a pollutant, and once California made clear that it and several other states were going to impose their own improved auto-mileage standards if the federal government did not, the major auto companies saw the handwriting on the wall and entered into negotiations with the Obama administration on a deal everyone could live with—but one that would push out the boundaries of technology and innovation. What the automakers like about the deal is that it now gives them long-term regulatory certainty and a level playing field, so when a company invests in these innovations it knows everyone else will have to as well.

Once we put in place these steadily rising efficiency standards across the nation, a price signal—a tax on carbon and/or an increase in the federal gasoline tax—would reinforce them. People would have even greater incentives to look for more efficient homes, cars, and appliances, which the market would have made available thanks to the performance standards. “Then you have this huge market signal pulling you where the government is pushing you,” said Harvey.

Finally, when the market and the efficiency standards are both driving behavior in one direction, this creates a major incentive for private-sector investment and innovation. “California building codes get tighter every three years,” said Harvey. This has spawned ever more sophisticated window manufacturers, heating-and-cooling equipment producers, and insulation makers. These companies, in turn, have become a lobby for higher standards because with higher standards they have more customers for their higher-performing products and fewer competitors, especially cheap foreign competitors. “When Washington tried to pass a carbon cap, it got pecked to death by the vested interests,” said Harvey. “California passed a far more aggressive policy because the old vested interests from the fossil-fuel industries and the [U.S.] Chamber of Commerce have been supplanted by new vested interests that are part of this virtuous cycle.”

These new interests know that if they can meet California’s standards, they can compete against anyone globally. This, in turn, gives both government and business the incentives to invest more in research and development. The pipeline of new products steadily drives more efficiency, making it easier and cheaper for consumers to adjust to a price signal. “The price signal becomes a transformation device, not a punishment device,” said Harvey. “If I make gasoline more expensive but I have access to great electric car batteries at falling prices, it doesn’t matter.” The consumer ends up saving money.

Putting all three together—efficiency standards, carbon prices, and innovation—creates a powerful engine for driving down the price for clean power and driving up demand for their production. (See Harvey’s graphic above.) “And then your innovation radically increases,” said Harvey, “because the venture capital guys see a market and the finance guys see an income stream and that really starts to change the world.” Harvey added that this is precisely the ecosystem that China is trying to put in place. “They want to have the highest-performing globally competitive businesses in the clean-energy space, and that is exactly where they are going.”

We wish we could say the same for America. But we can’t. America’s choices are clear: We can opt for living with the vicious energy-climate cycles set off in 1979 and 2010 that are making us less secure, less healthy, less wealthy, and more exposed than ever to the whims of the two most brutal forces on the planet—the market and Mother Nature. Or we can set in motion our own virtuous cycle that makes us healthier, more prosperous, more secure, and more resilient in today’s hyper-connected world.

Given the dangers and disruptions posed by the first choice and the economic and strategic benefits offered by the second, we consider the proper alternative to be obvious. We hope that a majority of Americans will soon see it that way as well. It is not at all an exaggeration to say that our future and the planet’s future are riding on it.