The natural vegetation of the Gower plateau is stunted oak-ash forest and scrub. Where exposed to the westerly winds, heathland develops, but in the deep combes and along the old cliffs a thicker forest is to be expected.

J. G. Rutter, Prehistoric Gower

ONLY A SMALL AREA of the peninsula, some 7 per cent, is woodland. As always in Gower, however, there is a great variety of habitats and they range from ancient woodlands through secondary woodlands to modern conifer plantations. In particular Gower contains one of the most extensive areas of ash woodland in Wales and is near the western extreme of the habitat’s range in Britain. These woodlands, which are of European importance, have developed along the series of largely interlinked valleys and ravines cut into the limestone and also on coastal slopes and cliffs, where there are unique transitions through scrub to sand dunes, freshwater marsh and salt marsh. Elsewhere they give way to fields and, particularly in the northeast of the peninsula, the intermixed fields and woodlands are a characteristic feature of the area, the subboscus, the lower part of the Welshry wood. The hedges that define the fields are themselves a significant wildlife habitat and are also important for historical and cultural reasons. They provide an essential refuge for many woodland and farmland plants and animals and are thought to act as wildlife corridors allowing movement and dispersal between other habitats. Gower is also an area of drystone walls and stonefaced banks and in some areas of the peninsula these are an important component of the landscape, with their own characteristic flora and fauna.

The hedges and walls enclose a considerable number of arable fields that have important populations of rare plants, dating back to the Neolithic period, growing alongside the crop. These plants, once denigrated as agricultural weeds, are now known as archaeophytes and have an immense cultural significance. It is becoming increasingly clear that Gower is one of the British strongholds of this ancient flora, but until recently little effort has been made to conserve these rare and interesting species. Other fields are pasture and some contain the remains of traditional orchards, once a characteristic feature of the area and now more or less ignored.

The woods, such as Ilston Cwm, Cwm Ivy and Kilvrough Manor Woods, contain a great diversity of trees and shrubs and a variety of vegetation communities and sub-communities are recognised, but generally they are dominated by ash and pedunculate oak in varying proportions. In some, such as Kilvrough Wood, hybrids between the pedunculate and sessile oak are common. At the top of the woodlands and on the steep slopes, where the soils are often thin, dry and calcareous, ash dominates (Fig. 143). Where the soils are moderate or deep, heavier and more acidic than those higher up, the oak tends to dominate the ash. Until recently wych elm Ulmus glabra was also present in large numbers, but its occurrence has been reduced dramatically by Dutch elm disease. Sometimes the woods also contain considerable amounts of small-leaved lime Tilia cordata, field maple Acer campestre and sycamore. Where there is sufficient light reaching the ground the invasive sycamore is often abundant in the shrub layer, along with large numbers of ash seedlings, but it only occurs occasionally as a canopy species. Although present almost everywhere it is generally more abundant on the deeper, heavier soils, which it appears to prefer. Spindle Euonymus europaeus and wild privet Ligustrum vulgare are frequent as well, although other plants which might generally be expected to occur in such conditions, especially buckthorn Rhamnus catharticus and spurge-laurel Daphne laureola, are rare in the shrub layer.

FIG 143. Ash woodland on the north Gower cliffs. Looking north along the escarpment from Cilifor Top in winter. (Harold Grenfell)

The ground flora of the ash woods is again rich and is usually dominated by ramsons and dog’s mercury Mercurialis perennis, together with hart’s-tongue fern Phyllitis scolopendrium and soft shield-fern Polystichum setiferum, which is very abundant on shaded slopes. Ferns such as male-fern Dryopteris filix-mas, lady-fern Athyrium filix-femina and broad buckler-fern are also locally frequent and in places dominant. In Parkmill Woods and Llethrid Valley there are populations of the locally uncommon royal fern, a dramatic plant that sometimes grows up to 3 metres high, hence its name (Fig. 144). This fern of wet woods was one of the species most heavily affected by the Victorian collectors. Several woods have dramatic spring displays of bluebells. Other notable species include wood spurge Euphorbia amygdaloides, toothwort Lathraea squamaria, herb Paris Paris quadrifolia, butcher’s broom Ruscus aculeatus and stinking hellebore, all of which are most abundant in eastern or southern Britain and, like the trees themselves, are nearly at the western or northwestern limits of their ranges in Gower.

Stinking hellebore, a perennial of woods and scrub on calcium-rich soils, was first recorded in Glamorgan around 1803 by Dr Turton, who discovered it between Parkmill and Pennard Castle. It was still there in abundance in 1840, when it was noted by Gutch, but it is now very rare in the Parkmill area even though the woodland appears to have changed little since Turton’s day. Although individual plants are long-lived, seedlings are rare and since it was formerly used as a medicinal plant, being given powdered as a remedy for worms, it may have been affected by over-collecting.

Areas of scrub woodland, dominated by ash, hazel and blackthorn, and in some places with buckthorn and dogwood Cornus sanguinea, survive in various locations on the south Gower cliffs. These woodlands were probably more extensive in the past, but repeated fires and intensive grazing by sheep have resulted in their replacement by gorse and heathland. Good examples of this type of woodland can be seen on the south side of Oxwich Point, where purple gromwell and pale St John’s-wort Hypericum montanum grow at the margins of the scrub, and in Ramsgrove Valley, where a variety of common whitebeam Sorbus porrigentiformis grows in the scrub. Three unusual trees, the small-leaved lime mentioned earlier, rock whitebeam Sorbus rupicola and wild service tree Sorbus torminalis, and two scarce shrubs, juniper and butcher’s broom, can be found in the rockier parts of Crawley Wood. There are also significant stands of butcher’s broom around Oxwich Point, which is its westernmost location in the peninsula.

FIG 144. Royal fern, a spectacular plant that sometimes grows up to 3 metres high. (David Painter)

The surviving fragments of oak-birch woodland have, where they are least disturbed, a varied flora that includes a number of upland species. The upper part of Penrice Wood, for example, has a luxuriant moss community including fuzzy fork-moss Dicranum majus, feather moss Hylocomium splendens, juicy silk-moss Plagiothecium undulatum and rose-moss Rhytidiadelphus loreus under an open canopy of birch and oak. Rose-moss can be particularly abundant on the floor of Gower woodlands, and is distinguished by a reddish stem, with the leaves having the appearance of being swept to one side of the stem and branches. In the upper part of Clyne Wood there is an open wood of oak and birch with hazel, alder buckthorn Frangula alnus and crab apple Malus sylvestris occurring alongside wood horsetail Equisetum sylvaticum and lemon-scented fern Oreopteris limbosperma.

Berry Wood, near Knelston, is an example of ancient oak woodland with coppice standards, which is situated on poorly drained glacial drift over the Millstone Grit (Fig. 145). Both pedunculate and sessile oaks are present, together with ash, hazel, grey willow Salix cinerea, rowan and aspen Populus tremula. The oldest oaks are estimated to be around 200 years old and are located on the western side of the wood. The remainder of the wood is much more recent and is made up of even-aged stands of oak, birch and ash. This suggests that much of the wood was felled at some time and allowed to regenerate naturally. A number of other Gower woods, such as Prior’s Wood, are examples of secondary woodland. Here the woodland canopy is made up of a considerable number of species including sweet chestnut, beech, ash, alder, birch, sessile oak, elm and small-leaved lime. This variety, together with evidence from old maps, which show that the site was originally called Priors Meadow, suggests that the wood has developed as a result of natural regeneration, probably aided by planting in the Victorian period. Parts of many other Gower woodland blocks are also secondary woodland, including Oxwich Wood, where large areas were affected by extensive limestone quarrying in the past.

Several areas, particularly at Kilvrough and the southwestern end of Park Woods, have in the past been planted with beech. Although the beech dominates, ash is often also frequent along with other elements of semi-natural woodland including a field layer dominated by bluebells, ramsons, wood anemone Anemone nemorosa, lords-and-ladies Arum maculatum and enchanter’s nightshade Circaea lutetiana. The Forestry Commission started planting in Glamorgan in 1921. Regarding Gower, the Commission’s guide to the Glamorgan Forests, published in 1961, noted, ‘Its woodlands of oak, beech and other broadleaved trees, stand on southward-facing slopes and are very much in the public eye. Therefore their management is closely concerned with retaining the scenic amenities, though at the same time it is believed that valuable timber can be grown and harvested without ever causing harm to the peninsula’s marvellous views.’ The main blocks of forest in Gower are Park Woods, Mill Wood and Mead Moor. Conifers planted in Park Woods and Mill Wood by the Forestry Commission included European larch Larix decidua, Corsican pine Pinus nigra var. maritima and Sitka spruce Picea sitchensis. Mill Wood is an ancient woodland that was later an estate wood and as a result it has a large number of tree species including oak, ash, beech and small-leaved lime. The flora underneath these trees is interesting and varied with plants such as wild daffodil Narcissus pseudonarcissus ssp. pseudonarcissus. Scattered throughout the wood are large, old, veteran trees which themselves support a number of animal and plant species. There are also the remains of a sixteenth-century corn mill that gives the wood its name and which still retains three large millstones.

FIG 145. Berry Wood, near Knelston, a nature reserve managed by the Wildlife Trust. (Harold Grenfell)

The most important wooded common is Bishopston Valley, which is owned by the National Trust, although woodland has also developed on other commons where grazing has ceased, such as Newton Cliffs and Summerland Cliffs. Bishopston Valley, however, contains both ancient and recent secondary woodland and the underlying limestone has produced a rich flora that includes both small-leaved lime and wild service tree. The damp and shady woodland floor with its carpet of rich leaf litter and rotting wood provides a variety of habitats, which have a rich invertebrate fauna, including snails, millipedes, woodlice and ground beetles. The land winkle Pomatias elegans, the only winkle found on dry land, common or two-toothed door snail Cochlodina laminata and tree snail Balea perversa are locally characteristic of calcareous woodland such as this. The land winkle is easily recognised as it carries a shell lid (operculum) on the rear of its foot, while the frontal part of the head is prolonged into a snout. It moves by lifting one side of its foot after the other, appearing to move forward on two feet. The tree snail is also unusual (perverse) because the whorls on its shell are coiled anticlockwise with the aperture on the left, rather than the more usual clockwise direction. The shell has a distinctive turret shape and is up to 1 centimetre tall.

Centipedes and millipedes, otherwise known as myriapods (literally many feet) are also common in this habitat, and Gower is a particularly interesting area for these animals. At the northern end of Park Woods near Llethrid, for example, there is an exceptional mean overwintering density of nearly 800 individual millipedes per square metre, 16 different species being present including a flat-back millipede Brachydesmus superus, a snake millipede Ophyiulus pilosus and a spotted snake millipede Blaniulus guttulatus. Five species of centipede have also been recorded from the site, a stone centipede Lithobius variegatus, Geophilus insculptus, Strigamia acuminata, Brachygeophilus truncorum and Haplophilus subterraneus. This latter species is one of the longest and broadest of the British ‘geophilid’ or ground-loving centipedes. It is up to 70 millimetres long, and it may be 1.5 millimetres at its broadest point. Bishop’s Wood was one of the three sites from which Geophilus osquidatum was first recorded in Britain and the site of the second British find of Chordeuma proximum.

The harvestman Sabacon viscayanum ssp. ramblaianum was also first discovered in Britain, in 1980, in the woods at Parkmill. It has now been found in 22 localities in South Wales. Because the early finds were close to industrial workings it was suggested that the harvestman had been introduced to Britain, but since these sites invariably include old, damp woodland, which is the usual habitat of the species, it is considered instead to be a ‘relict’ species whose range was once more extensive, but which has since become fragmented.

Little is known about the flies of the Gower woods and many records date back to the 1950s and 1960s when Fonseca (1973) extensively surveyed Nicholaston Wood and Oxwich Wood. He recorded a large number of scarce flies associated with old woodlands including Coenosia stigmatica, Hydrotaea velutina, Helina abdominalis, Fannia gotlandica, Fannia carbonaria, Eustalomyia vittipes, Delia tarsifimbria and Aulacigaster leucopeza. It is thought that many of these flies disappeared when dead trees were removed around 1960, although at least one of the flies recorded by him, the hoverfly Brachypalpus laphriformis, was still present in the mid-1990s.

Other insects, however, are known to be numerous in the woodlands, especially in the open sunny glades. A varied shrub layer on the glade edges will support a variety of woodland moths and the rich flora of grassy rides can support a large and important fauna of plant-feeding beetles, bugs and leafhoppers. The waved carpet moth Hydrelia sylvata is a highly localised species that occurs in woods in Gower that have a long history of coppicing and where there are open sunny areas with young specimens of the larval food plants, which are alder, birch, sallow and blackthorn (Fig. 146). The adult moths are on the wing in June and July, resting by day among the bushes, but they can also be occasionally found on tree trunks. The larvae feed between July and August, pupating in September to overwinter in an earthen cell until they emerge the following July. Because of this limited period on the wing and the fact that it occurs at a low density over much of its range it is likely that the species is under-recorded.

FIG 146. Waved carpet moth, a highly localised species which occurs in woods that have a long history of coppicing. (Barry Stewart)

Two small tree-dwelling species also often overlooked by the casual observer are the purple hairstreak Quercusia quercus and whiteletter hairstreak Satyrium w-album butterflies. The purple hairstreak (Fig. 147) is a true woodland butterfly and the caterpillars, which are extremely well concealed, feed mainly on oak buds and leaves. This close association is reflected in its scientific name, which uses the Latin word quercus, meaning ‘oak’, twice. The numbers of adult butterflies vary greatly from year to year, but it has been recorded from Oxwich, Nicholaston, Llethrid, Crawley and Park woods. The adults typically fly high around the tree canopy and only rarely descend to paths and clearings, the females tending to be more visible than the males. Purple hairstreaks are aggressive butterflies and will attack other insects which fly into their territory, even wasps. They feed on the sugar-rich honeydew deposited by aphids on ash and aspen leaves. The whiteletter hairstreak is a very local species and its caterpillars feed exclusively on elms, which are fast disappearing due to Dutch elm disease. There are only a few records from well-monitored sites such as Bishop’s Wood and Oxwich. The adults spend a lot of time visiting bramble and privet blossom for the nectar and the honeydew left by aphids. Elsewhere the species may be seen wherever wych elm, or other regenerating elms, are found, but it is unlikely that more than one or two individuals will be present. In contrast speckled wood Pararge aegeria is a common and widespread species found in a variety of locations, not confined to woodland.

FIG 147. Purple hairstreak butterfly in Llethrid Cwm. (Harold Grenfell)

The Gower woodlands support a wide diversity of breeding birds, as well as providing shelter and food for migrants in spring and autumn. In particular Bishopston Valley is recognised as being especially important for the variety and quality of the breeding bird community and the number of wintering species. The great spotted woodpecker Dendrocopos major is common in both coniferous and deciduous woodland and the characteristic ‘drumming’ of its bill against a resonant piece of wood, which is a means of declaring ownership of territory, is a frequent sound in early spring (Fig. 148). In contrast the lesser spotted woodpecker Dendrocopos minor is a much rarer bird in the peninsula, but it may be under-recorded, as unlike the great spotted woodpecker it is a difficult bird to find. It has been regularly sighted in the Oxwich Bay area over the last forty years, and also occurs in Clyne Woods.

Another breeding bird in the woods is the buzzard Buteo buteo. This is the commonest bird of prey in Wales and the wooded valleys and mixed agriculture in Gower combine to create an ideal habitat. Other birds include summer migrants such as blackcap Sylvia atricapilla and chiffchaff Phylloscopus collybita, which normally breed in deciduous woodlands where there are mature trees and a good understorey. The tiny insectivorous goldcrest Regulus regulus and the nuthatch Sitta europaea are also present along with the treecreeper Certhia familiaris, which occurs in most of the deciduous woodlands. Little owl Athene noctua and tawny owl Strix aluco are widespread and common breeding residents in the Gower woodlands. There are recent signs, however, of a decrease in numbers, the reasons for which are not clear. Of the two species the little owl is the less abundant, but it can still be seen fairly easily, particularly in the west of the peninsula. Regarding the long-eared owl Asio otus Dillwyn recorded that ‘In December 1825, Mr Talbot shot one at Penrice, where the specimen is preserved; and three or four have since been killed in Gower, but it is far from common in this neighbourhood.’ Perhaps not surprisingly, long-eared owls are now scarce throughout Britain and nest almost exclusively in conifers. The last confirmed breeding record in Gower was in 1919, although a single bird was found dead in Mill Wood in 1987. As it is the most nocturnal owl it is easily overlooked and may still be present.

Finally, there used to be a sizable colony of rooks Corvus frugilegus in Oxwich Wood behind the church. In 1975 this was one of the largest rookeries in Gower, but the last record, of only 25 nests, was in 1992; the birds seemed to have moved to the nearby Pittsog’s Wood, where there were 22 nests in 1993. The bird’s optimum habitat is a mixture of arable and grazing land, which ensures a constant food supply throughout the year, and Gower would therefore appear to be an important area (Fig. 149). There is indeed a concentration of rookeries on the better land in the south and west of the peninsula. Some of these sites may be of considerable antiquity. Intensive surveys during the 1980s and early 1990s found that 811 nests at 16 rookeries in 1983 had declined to 658 nests at 17 rookeries in 1992. Stouthall was consistently the largest rookery in the area throughout this period, with 278 nests in 1984, making it one of the largest rookeries in Wales at the time, but it declined when many of the beech trees had to be felled as they were considered to be unsafe. Although the overall number of nests varied from year to year, sometimes quite noticeably, the general trend from the mid-1980s onwards has been one of a gradual reduction in numbers. Cereals are an important food source for rooks and a clear correlation can be drawn between the decline in the area of cereals grown in Wales and the numbers of rooks. The crucial months for young birds are July and August, when they are dependent on a source of grain.

FIG 148. Great spotted woodpecker in Cheriton Wood. A common species in both deciduous and coniferous woodland. (Harold Grenfell)

FIG 149. Rook foraging in winter near Reynoldston. (Harold Grenfell)

British bats can be divided into two groups, depending on their roosting requirements, cave and woodland bats. Both groups are well represented in Gower, although the cave-roosting species are the most obvious and thought by many people to be the only bats present. In contrast, the woodland bats are secretive and choose roosting places where they are difficult to see, and as a result are seldom encountered except when they form nursery roosts in buildings. They include the common, or 45kHz, pipistrelle Pipistrellus pipistrellus and the soprano, or 55kHz, pipistrelle P. pygmaeus.

Almost all studies of pipistrelle bats until a few years ago assumed that there was only one species in Britain, but, as the alternative names suggest, the use of the ultrasonic bat detector has identified two clearly different species. The other predominantly woodland bat is the noctule Nyctalus noctula, which is found in the woodlands in Parkmill and Oxwich and in parts of Mumbles. This is the bat often seen flying high in the clear air. The brown long-eared bat Plecotus auritus is also a relatively common woodland bat that roosts and hibernates mainly in trees and buildings. It is known as the ‘whispering bat’ and picks food off the leaves of trees, listening and watching for the insects and spiders as they move about on the foliage. Natterer’s bat Myotis nattereri, Brandt’s bat M. brandtii and whiskered bat M. mystacinus are also associated with woodland and forage along hedgerows and the woodland edge for flies and other insects. In addition they catch a considerable number of spiders. Another bat of parklands, pasture and woodlands, the serotine, has been found in the roof of a house in Swansea and a good visual identification has been made of large bats seen flying near Llanrhidian.

It would be premature to say that all the species of bats in Gower are known. More survey work needs to be done, with the bat detector, for species such as barbastelle Barbastella barbastellus that are associated with areas of old woodland. Most of the Gower woods are probably managed too well to leave the kinds of splits, areas of flaking bark and crevices this species favours as roost sites, but it might be worth searching woodland near Ilston. Bechstein’s bat Myotis bechsteinii is another species that would be worth looking for. It roosts in holes in trees and prefers old trees with dead branches. The areas of mature woodland in Parkmill, Oxwich and Bishopston Valley all have features that could suit this species.

Once the fauna of the Gower woods was more exotic than it is today. Dillwyn (1848) says that the wild cat was still occasionally seen in Clyne Woods and to the north in the Neath Valley. It was regarded as ‘vermin’ and heavily persecuted, as he noted in relation to activities at Margam, to the east of the peninsula:

During an active extermination of the vermin in Margam Park, which commenced in 1824, twelve of these animals were killed within two years; and my friend Mr Talbot says that one of these, which is now preserved at Penrice Castle, weighed twelve pounds; and he was told by his keepers that some of the others were considerably larger.

Persecution of vermin was a continuing theme in Gower, as elsewhere, during this period and the Reverend Davies (1894) mentions in his survey of the parishes of Llanmadoc and Cheriton (and referring to Cheriton church) that:

I was informed by several old people that it was the invariable custom when anyone killed vermin, such as weasles, stoates, polecats, &., to bring them to the churchyard, and nail them up in a certain ash tree. At the annual vestry meeting, held on Easter Monday, these animals were counted and those who killed them were paid so much a-piece out of the church rate; a guinea was allowed for a fox.

Dillwyn also recorded that the pine marten Martes martes occurred in the peninsula and it is true that until the nineteenth century pine martens were found throughout much of mainland Britain. However, fragmentation of habitats, persecution by gamekeepers and martens being killed for their fur drastically reduced this distribution. Today the total population for England and Wales is estimated to be only 150 individuals, although it may be as low as 40. The species is therefore unlikely to return to Gower.

A polecat Mustela putorius was recorded in November 1969 by Pip Hatton, the Nature Conservancy Warden, at the side of the road near Cilibion. He noted, ‘It was caught in the headlights on the grass verge and instead of moving, curled its body round and snarled at the lights.’ Polecats are medium-sized animals with distinctive black and white facial markings. As indicated by the above sighting they are predominantly nocturnal, and tend to hunt on the ground, avoiding swimming or climbing, with rabbits being the main prey. The preferred habitats are woodland edges, farm buildings and field boundaries, and polecat territories are closely related to the presence of rabbit warrens. The animal is now widespread in Wales and is expanding rapidly into England.

Badgers are again widespread and there are about 400 setts recorded in Gower, but it is difficult to assess the size of the population (Fig. 150). Many of the setts are in ‘textbook’ positions at the edge of woodland adjacent to pasture, although they are also found near the tops of the Old Red Sandstone hills which form the spine of the peninsula. Setts are also located in sand dunes, close to the seashore. A badger has even been found asleep on the rocks at Mewslade.

A national population study conducted in the mid-1990s by Bristol University suggested that badger numbers are generally stable in the UK, but unfortunately illegal persecution continues. About one-third of the Gower setts have evidently been interfered with and the Glamorgan Badger Group patrols the most vulnerable setts at irregular intervals. Many badgers are also killed or injured as a result of road traffic accidents. This is especially so in the tourist season, when the amount of traffic on the peninsula’s roads increases dramatically. Hot summers can also increase the number of road deaths, because in dry weather, when earthworms do not come above ground, badgers forage further than normal from their setts and can be at greater risk from road traffic. Other issues affecting the conservation of badgers include the dramatic rise in the number of cattle with bovine tuberculosis, an infectious and contagious disease of cattle caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium bovis. Since the mid-1970s thousands of badgers in Britain have been culled in response to outbreaks of tuberculosis, because of circumstantial evidence that badgers spread the disease. Thankfully there has been no culling in Gower to date and this crude approach is now becoming discredited.

FIG 150. Badger in Nicholaston Wood. (Harold Grenfell)

The native common or hazel dormouse Muscardinus avellanarius was recorded from Berry Wood in 1969, but has not been detected there since. Apart from bats, the dormouse is the only British mammal to hibernate (in the true sense of the word) and their name is thought to originate from the French word dormir, meaning ‘to sleep’. The animal is no longer as widespread or abundant as its name suggests and its distribution is now limited to the south and west of England, parts of Wales and a few outlying populations in the north of England. Dormice are mainly confined to those habitats that provide a rich variety of edible fruit and seeds within a complex physical structure, such as woodlands and areas of species-rich shrubs such as hedgerows. They very rarely come down to the ground, spending most of their time climbing among branches in the hunt for food. In particular they require a sequence of suitable foods to be available in the tree and shrub canopy through the summer. While they are often thought of as woodland species, the earlier literature mentions a much wider range of habitats including hedges, thickets and commons. Nests have also been found low down in coastal scrub, less than 1 metre above the ground, close to the grass that is used to construct them.

The current status of the dormouse is not clear, although a recent survey found signs of its presence in a number of locations. In 1965 a dormouse nest was found in Cilibion Plantation, a conifer plantation with a broadleaved edge consisting of coppice with standards, and in 1998 there was a record of a distinctively gnawed hazel nut at the same site. The other stronghold for dormice appears to be Gelli Hir Wood, where there was a sighting in 1999 of an adult in a bird box and a gnawed nut was found in 2001. Dormice are easily overlooked, however, being very elusive animals that are rarely seen even in parts of the country where they are relatively common. In addition they occur in very small numbers, at a level of only six to ten per hectare, even in prime habitats. They are also small and strictly nocturnal and during daylight hours are fast asleep in their nests. Dormice are regarded as poor colonisers and are therefore prone to die out in isolated habitats, a viable population needing access to at least 20 hectares of suitable territory. Much more research is needed before the distribution and strength of the Gower populations can be properly understood.

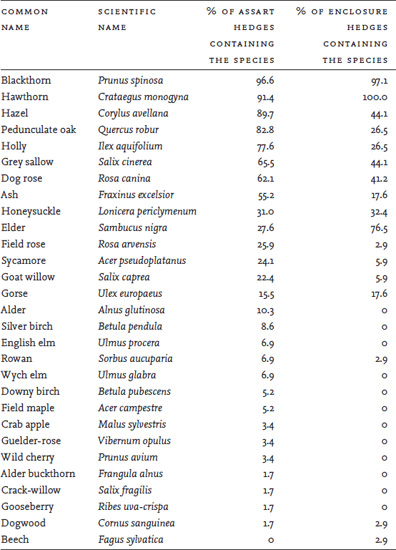

There are two generally recognised hedgerow types, assart hedgerows and enclosure hedgerows, which correspond to the ancient and planned countryside described by Oliver Rackham (1986). Both types occur in Gower and intimately reflect past land use in the peninsula. Assart is the informal and often pre-medieval practice of creating farmland from previously untouched woodland, heathland and fenland, whereas enclosure is the deliberate planting of hedges to enclose formerly open ground, which was usually the medieval field system. Assart hedgerows normally therefore have a much richer flora and fauna than enclosure hedges as they have been derived from the original woodland or from rough wood pasture, unfarmed heathland etc. Some enclosures have been dated as far back as the fifteenth century, but most date from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries when the popular hedging plants were hawthorn and blackthorn.

The areas of assart and enclosure hedges can be easily identified by looking at a modern large-scale map. The assart areas have an intimate pattern of small fields, the boundaries of which are often curved or very irregular and are sometimes massive structures full of mature trees. Some roads can be clearly seen to cut through this pattern and the fields thus pre-date the road. This is the classic ancient countryside as described by Rackham and is formed as a result of medieval or pre-medieval assarts. In areas of planned countryside, on the other hand, the field system generally derives from post-medieval enclosures and the boundaries are usually straight and enclose larger fields. The enclosure hedges are often treeless. This clear division often breaks down around settlements where small parcels of land are directly associated with houses or are used as allotments or paddocks.

The classic example of assart hedgerows in Gower is the community or parish of Llanrhidian Higher, which stretches inland from Wernffrwd and Llanmorlais and is bounded by the commons to the south (Fig. 151). Llanrhidian has the largest area of assart hedgerows in the peninsula and undoubtedly the best hedges in terms of geographical extent, general antiquity and total hedgerow length. The fields here in the subboscus are mainly very small, with herb-rich grassland, and there is a large amount of ancient woodland, which complements the value of the hedgerows (Table 12). The hedges are well stocked with trees, mostly pedunculate oak, with some ash and frequently with shrubs that have grown to maturity. Often the trees have grown from coppice or an old laid hedge. They are usually very high and wide and have a substantial bank. Dense bases surrounded by bramble are a frequent feature and this both protects the herb layer from grazing and provides a good habitat for invertebrates and birds. As in all areas of Gower, hawthorn and blackthorn are frequent, but here they are complemented by hazel, holly Ilex aquifolium, grey sallow Salix cinerea and dog rose Rosa canina. Other trees and shrubs include crab apple and field maple. There is a diverse herb layer that includes species such as tutsan Hypericum androsaemum, scaly male-fern Dryopteris affinis, betony Stachys officinalis and devil’s-bit scabious. The latter two species demonstrate that hedges can be a reservoir for grassland species as well as woodland species.

FIG 151. Hedgerows in winter near Wernffrwd. (Harold Grenfell)

TABLE 12. Trees and shrubs of Gower hedgerows. (Adapted from Lawrence & Higgins, 1998)

In contrast the entire western end of the peninsula, west of a line from Landimore to Port-Eynon, is a landscape dominated by enclosure hedgerows. The wildlife value of these hedges may be less than that of the assart areas, but it is still important. The areas of enclosure are still very much as they appear on the estate and parish maps of the late eighteenth century and the hedges are thus at least 200 years old. The fields are not over-large, the hedgerow network is still relatively dense and the hedges are often very substantial, providing a good habitat for breeding birds, and species such as yellowhammer and song thrush Turdus philomelos are frequently recorded.

Like many areas of Britain, Gower has its own style of drystone walling. Here, given the large areas of common land, the walls are built with an overhang on the outside to help keep animals out of the field they enclose. Walls provide a variety of different habitats and microclimates in a comparatively small space and there is always an exposed, wet side and a drier, warmer side. Even a well-maintained wall contains numerous holes providing habitats for a variety of invertebrates including spiders, woodlice, millipedes, bees and wasps. Wood mice and bank voles Clethrionomys glareolus, toads and slow-worms also find the cavities in walls attractive. A semi-derelict wall is more attractive than a well-maintained one since there are more sheltered spaces and more is covered in soil. However, such a condition is relatively short-lived, and once it is reduced to less than half its height the value of a wall for wildlife decreases considerably. They therefore need to be sympathetically maintained if they are to continue to be of interest (Fig. 152).

Probably the earliest survey of the flora of Gower walls was undertaken by the Caradoc and Severn Valley Field Club, who had their first ‘Long Meeting’ in Gower during July 1893 and recorded ‘walls richly covered with moss and ferns, among which were noticed the wall-rue Asplenium ruta-muraria, maidenhair spleenwort, black stalked spleenwort, scaley fern, hart’s tongue, &c., &c.’ (Anon, 1896). In crevices ivy-leaved speedwell Veronica hederifolia and white stonecrop Sedum album can be found. The latter is probably introduced, but some authors think it may be a native plant of southwest Britain. Lichens also grow well on the stones. A variety of snails can be found including common snail, which uses walls as hibernation sites, rock snail Pyramidula rupestris, strawberry snail Hygromia striolata and hairy snail H. hispida. Great black slug Arion ater, large red slug A. rufus and hedgehog slug A. intermedium are also present in many walls.

FIG 152. Drystone wall above Devil’s Truck, near Rhossili. (Harold Grenfell)

In the peninsula there are compact nucleated villages with a subsidiary pattern of single farms. The fields tend to be large and regular in shape and have descriptive names in English such as Green Field, Limekiln Close and Longfurlong, the latter name arising because the field had previously been managed as part of an open common field. This is in clear contrast to upland Gower, where single farms and hamlets dominate and the names of the small irregularly shaped fields are Welsh. In the early 1970s Michael Williams (1972) used the field-name data from tithe redemption surveys completed between 1838 and 1848 to plot the precise boundary of the Welsh and English cultural frontier in Gower. Allowing for the greater stability of field names compared with the spoken languages he claimed that they represented the linguistic situation of the late 1700s and early 1800s. His work confirmed, as expected, that peninsular Gower was the core of the English-speaking area and that upland Gower was Welsh-speaking. The neck of the peninsula between Pen-clawdd and Swansea was the transition zone between the two areas, where a belt of woodland, the coed or boscus, began and continued northwards. Similar work around the same time by Emery using farm names taken from the first edition of the Ordnance Survey one-inch map published in 1830 suggests a boundary between English and Welsh Gower running from northwest to southeast along a line of common land from Welsh Moor to Clyne Common.

The plants that grow in the arable fields include not only the crop plant itself, but also other species. There has been debate for some time over the status of arable plants in Britain, and whether they are native or introductions, but it is now almost certain that the vast majority of British arable plants are not strictly native. Instead they were probably brought here by Neolithic farmers as agriculture spread to Britain around 3,500 years ago. As seed corn was exchanged between neighbouring farms the plants were transferred with them. With no effective methods of control, distinct communities of plants developed over the centuries alongside the intended crop plant. These communities, which show slight variations in species composition depending on the climate and soil type, appear now to be completely natural and their ancient ancestry is not appreciated. With the assistance of new genetic analysis these plants might reveal their origins and provide a record of the movement of agriculture into Britain. Different plants probably arrived in various areas of Britain, as farming spread from separate parts of Europe and the present patterns could be ‘fossils’ of former distributions. Financial support and advice is now available to farmers in Gower who sign up to the arable options within Tir Gofal, the Wales agri-environment scheme, and they are encouraged to leave the field margins unsprayed and unfertilised. Without the help and support of farmers the outlook for arable plants is very depressing.

As much of the recent history of farming in Wales has been involved with grazing animals it is easy to forget how important arable cultivation was in the past. From the Neolithic period onwards cereals were extensively cultivated, especially in lowland coastal areas such as Gower. The arable plants found today represent just a fragment of this rich past, much of which has been destroyed in the last fifty years or so by the intensification of arable farming, which has involved massive advances in technology and huge increases in efficiency, crop quality and crop yields. Many species of plants which once grew in the fields alongside the crop have declined, some to the point of extinction, since they cannot compete with dense highly fertilised crops. As a result arable fields now contain a large proportion of Britain’s most endangered plants and arable field margins are identified as one of the highest-priority habitats. In the New Atlas of the British and Irish Flora (Preston et al., 2002) arable plants are identified as the group that has undergone the most remarkable decline in distribution during the last thirty years.

In the older literature many of these species are referred to as ‘arable weeds’, being definitely, as the dictionary defines it, ‘a plant growing where it is not wanted’ as far as the farmer was concerned. New descriptions use the term ‘arable plants’ in recognition of their conservation importance. Probably the most well-known arable plant is the poppy Papaver rhoeas, but it is interesting that, compared to England, poppies are relatively uncommon in Wales and fumitories, a close relative, occur in abundance instead. Nationally scarce species found include tall ramping-fumitory Fumaria bastardii and common ramping-fumitory F. muralis.

In contrast to many other parts of Britain, the continuous history of mixed farming in Gower has preserved the habitat of what was once a plentiful and diverse arable flora. A study by Quentin Kay (1997a) showed that the arable plant communities in Gower are still very much richer in species than the increasingly impoverished arable floras that are now the normal situation for lowland Britain. The arable plants also often extend right across the field, rather than being mainly confined to the margins, as so often is the case in England. This has an additional advantage in that wintering flocks of birds prefer to forage in the centre of the fields away from the hedges where there may be predators.

Although many of the plants are still present, they are considerably reduced in abundance. While it is still not too difficult to find Gower fields with scattered specimens of increasingly rare plants like corn marigold Chrysanthemum segetum (Fig. 153), sharp-leaved fluellen Kickxia elatine or wild radish Raphanus raphanistrum these species are no longer as common as they were twenty years ago. Unfortunately there are no recent records for some arable plants that used to occur extremely locally or as rarities, such as corn chamomile Anthemis arvensis and lesser snapdragon Misopates orontium, but it seems highly likely that they will be found again, along with other species not previously recorded from the area. Until 2002 broad-fruited cornsalad Valerianella rimosa was thought to have been extinct in Wales until it was found in a Gower field, the first record for fifty years. Similarly, small-flowered catchfly Silene gallica, once thought to be lost from Gower, was recorded again in 2003.

Arable plants vary in their adaptation to the specialised habitat of cultivated land, and three broad classes are recognised. First are obligate plants, which only grow in cultivated land. Wild radish is a good example since it appears to grow only in cultivated land throughout its world range. Some semi-obligate plants grow mainly in arable land in Britain, but also occur in some isolated natural habitats where they seem to be native. It seems likely, therefore, that they have originated from weed populations in the past. The nit-grass found on the Gower cliffs probably originated in this way, first arriving in the peninsula as an annual weed of cultivated land. Like the nit-grass, arable plants of this class are often ecologically restricted, declining on arable land and rare or scarce in their natural habitats. The second class is facultative plants. These grow both as plants in arable crops and also in other habitats in the same geographic area. A familiar example is annual meadow-grass Poa annua, which is now the most widespread and abundant non-crop plant in the arable fields. Annual meadow-grass is, as its name suggests, an annual, but facultative plants are often perennials, such as creeping buttercup Ranunculus repens. Many facultative plants show considerable variation within the species, with clear genetic differences between arable and non-arable populations. The third class is casual plants. These are species which occasionally appear as arable plants, originating either as a result of natural dispersal from other habitats in the same area or as introductions with seeds or fertilising material such as slurry. They are normally non-persistent and usually grow as isolated individuals. Examples from Gower include rosebay willow-herb Chamerion angustifolium and common gorse.

FIG 153. Corn marigold, an increasingly rare plant, in a field near Middleton. (Harold Grenfell)

TABLE 13. The 20 most abundant arable plants in Gower. (Adapted from Kay, 1997a)

| RANK | COMMON NAME | SCIENTIFIC NAME |

| 1 | Annual meadow-grass | Poa annua |

| 2 | Fat hen | Chenopodium album |

| 3 | Chickweed | Stellaria media |

| 4 | Pineappleweed | Matricaria discoidea |

| 5 | Common orache | Atriplex patula |

| 6 | Prickly sow-thistle | Sonchus asper |

| 7 | Perennial rye-grass | Lolium perenne |

| 8 | Creeping buttercup | Ranunculus repens |

| 9 | Redleg | Persicaria maculosa |

| 10 | Shepherd’s purse | Capsella bursa-pastoris |

| 11 | Pale persicaria | Persicaria lapathifolia |

| 12 | Groundsel | Senecio vulgaris |

| 13 | Knotgrass | Polygonium aviculare |

| 14 | White clover | Trifolium repens |

| =15 | Black bent | Agrostis gigantea |

| =15 | Scentless mayweed | Tripleurospermum inodorum |

| =17 | Scarlet pimpernel | Anagallis arvensis |

| =17 | Spear thistle | Cirsium vulgare |

| 19 | Cut-leaved dead-nettle | Lamium hybridum |

| 20 | Field woundwort | Stachys arvensis |

Some of the long-established arable plants are distributed very locally in Gower, even though they occur in some abundance, at least in some fields, in the areas where they occur. A notable example is annual nettle Urtica urens, which is a locally abundant and problematic plant in many fields in the Rhossili and Pitton area, but has not been seen elsewhere. Field pennycress Thlaspi arvense and henbit dead-nettle Lamium amplexicaule are also only noted from the Rhossili area.

Bryophytes (mosses, liverworts and hornworts) are a characteristic component of cultivated land in Britain, but knowledge of their status, distribution and ecology lags well behind that of arable vascular plants. A number of species are considered members of a typical arable bryophyte community, including the liverworts Riccia glauca and R. sorocarpa, and around fifteen mosses. A fairly large proportion of the known arable-land bryophyte flora occurs in Gower, but very little research on this subject has been carried out. Survey work is needed to understand the distribution, status and occurrence of bryophytes in different crop types and under various management regimes. The hornworts in particular appear to be declining in arable fields. Not much is known about them and only two species have been recorded in Gower to date, the very rare Anthoceros agrestis, found on a muddy track at Burry Pill in 1963, and the uncommon Phaeoceros laevis. Once again more research is needed. In Britain hornworts generally behave as annuals, germinating in early summer and producing spores in early winter.

A large proportion of Gower fields are improved grassland, but a significant number, especially in the northeast of the peninsula, are examples of rhos pasture. Rhos pasture (from the Welsh rhos, moor) has been a feature of the South Wales landscape for centuries. It is the species-rich marshy grassland of western Britain and is a habitat that only occurs on the Atlantic seaboard of Europe. The pasture is found on unproductive, damp soils along valley bottoms and streamsides, on common land and wet hillsides, where traditional low-intensity cattle grazing or occasional summer hay cuts maintain the flower-rich turf. Wales contains half the rhos pasture in Britain, with Glamorgan accounting for around 10 per cent of the Welsh resource. Although the habitat is recognised as being of international importance and a small number of sites in Wales are specially protected as Sites of Special Scientific Interest, at the current rate of loss few sites will remain.

The Gower pastures support a characteristic flora with purple moor-grass and rushes, heath spotted orchid, tormentil, devil’s-bit scabious, cross-leaved heath, whorled caraway, bog asphodel, carnation sedge, marsh violet and meadow thistle Cirsium dissectum. Together with the Gower commons such pastures are a stronghold for the marsh fritillary butterfly, whose food plant is devil’s-bit scabious, and are important for breeding birds such as skylark, meadow pipit and reed bunting. They also support a wide diversity of invertebrates, reptiles and amphibians, which attract otters.

Although the fact is not well known today, historically Gower was always associated with fruit production and there were once a large number of orchards. The majority of these were in the area around the villages of Llanrhidian and Llangennith, the remainder being spread evenly across the peninsula. Walter Davies, in 1815, mentions Gower and notes that small orchards were ‘still pretty frequent there and produce an abundance of apples’. Many of the orchards are indeed small, but sadly some have disappeared completely and many are in a derelict state. As the trees finally die they are not being replaced. A total of eighty traditional orchard sites have been identified, but a survey in 1994 showed that just six orchards were still more or less intact. Only one of these six showed little or no tree loss, the remaining five being used for grazing, or for the storage of farm machinery. The residual sites are indicated by odd trees scattered around the area of the former orchard. A number of orchards have also been lost due to housing developments on the edge of Swansea, such as the development at Dunvant known as ‘Y Berllan’, the word berllan always signifying orchards in the Welsh language. A house built in 1894, beside the road from Caswell to Bishopston, was also originally called Berllan because it stood on the site of an old orchard.

Traditional orchards have many features that make them of value to wildlife and even in their present derelict state the Gower examples are important (Fig. 154). Fruit trees are relatively short-lived and as a consequence produce decaying wood more quickly than most native hardwoods, making them important refuges for invertebrates, and for hole-nesting and insectivorous birds. Old fruit trees are also an important habitat for mosses, liverworts and lichens, though there has not been a comprehensive survey of the remnant orchards. The tree blossom itself provides an early source of nectar for bees, moths and other insects that in turn attract a variety of birds. In the summer the canopy provides nesting sites and food for insect-eating summer migrants while in the autumn the fallen fruit provides a source of food for a wide range of animals, including insects, mammals and birds, particularly song thrushes, fieldfares Turdus pilaris and redwings T. iliacus. Orchards can also have a herb-rich grassland sward, which may be managed as a meadow or pasture, while shadier sites can give rise to plant communities that are more typical of the flora of hedgebanks. Yellow meadow ant mounds are often found in old undisturbed grasslands such as orchards.

FIG 154. Apple orchard at Frogmore Farm, the best remaining orchard in Gower. (Harold Grenfell)

There has been almost no research on the Gower orchards, and information is needed both on the wildlife of these areas and on the particular varieties of fruit tree that occur. The Glamorgan County History (Tattersall, 1936) describes the varieties grown in the county as mostly culinary, such as Bramley Seedling, Newton Wonder, Lord Derby and Lane’s Prince Albert, with some dessert apples including Beauty of Bath, James Grieve, Allington Pippin and Worcester Pearmain, but there are no site-specific records. An immense number of local fruit varieties exist in Britain, and these cultivars are an important wildlife element in their own right. It is possible therefore that varieties of apple particular to Gower once existed, and indeed they may still do so, remaining unrecognised perhaps on a single dying tree. Even now it is not too late, if there is the support of the farmers and landowners, to rescue the orchard heritage of the peninsula.

Despite the potential loss of the orchard heritage, the conservation of the woods and hedges seems assured. The larger areas of woodland are now protected by statutory designations, and through the efforts of the Coed Cymru initiative many of the small farm woodlands are under better management than they have been for decades. More still needs to be done, however, especially in relation to those woodlands on farms that are being managed under the Tir Cymen or Tir Gofal agri-environment schemes. Hedges too are being revitalised and managed more sympathetically for wildlife as part of these schemes. In contrast, the survival of arable plants depends very much on the continuation of relatively low-intensity arable farming, and the prospect for this is by no means assured.