By scummed, starfish sands

With their fishwife cross

Gulls, pipers, cockles and sails

Out there, crow black, men

Tackled with clouds, who kneel

To the sunset nets

Dylan Thomas,

Prologue from The Poems

DAUNTING, DRAMATIC and lonely are just a few of the words that have been used to describe the Burry Inlet and Loughor Estuary. It is an untamed place and one of the last refuges of real wilderness in this part of South Wales. From its seaward end, bounded by the long sandy finger of Whiteford Burrows National Nature Reserve in the south and Pembrey Burrows in the north, to the tidal limit close to Pontardulais and the M4 motorway it covers more than 9,500 hectares. It is the largest estuarine complex wholly within Wales and dominates the north side of the peninsula, forming a real divide between Gower and Llanelli to the northwest. At low water, due to the wide tidal fluctuations (about 8 metres on average) over 70 per cent of this vast area is exposed on a regular basis, revealing a shifting landscape of sandbars, mud and glistening water channels. During spring tides 1,400 million cubic metres of sea water enter and leave the estuary twice daily. The inlet and estuary is a complex region where salt water meets fresh water, sea meets land and the seasons and tide bring constant, but cyclical, change.

Estuaries are defined as the downstream part of a river valley, subject to the tide and extending from the limit of brackish water, while marine inlets are defined as areas where sea water is not significantly diluted by fresh water. Using these definitions most of the area under consideration is an inlet, but to many people, locals and visitors, it is simply ‘the Burry’ or ‘the estuary’ or ‘the Burry Estuary’ (Fig. 100). Together with the nearby estuaries of the Taf, the Tywi and the Gwendraeth (‘the three rivers’) the River Loughor forms a single functional unit around the inlet, and research has shown that there are important interchanges of sediment and species between the four areas. A substantial area of South Wales drains, from the source of the Loughor on the Black Mountain, through the estuary and inlet to the Bristol Channel.

The national and international importance of the area is reflected in a multitude of often overlapping designations. There are five Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) within and around the estuary and one National Nature Reserve (NNR); it is a Ramsar site under the 1971 International Wetlands Convention, a Special Protection Area (SPA) for wild birds, a Special Area of Conservation (SAC) under the European Habitats Directive, a Geological Conservation Review (GCR) site, and of course most of the inlet falls within the AONB. In addition there are extensive National Trust properties and six Wildlife Trust reserves along the southern shore. But the area is much more than the sum of its constituent parts.

FIG 100. Aerial view of the Burry Inlet and Loughor Estuary. (Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales)

In the more sheltered areas, where plants have been able to colonise the intertidal mud flats, the fourth largest area of salt marsh in Britain has developed. It currently covers 2,121 hectares (Fig. 101). When the salt marsh first began to grow is not known, but the now wooded limestone cliffs along the Gower shore were active sea cliffs 5,000 years ago so any marsh must have originated later. The marsh on the southern side has accumulated in the shelter of Whiteford Point, a shingle ridge, which seems to have originated as a glacial moraine later covered by sand dunes. Sediments forming the marsh derive mainly from the redistribution of glacial deposits, together with sand and shell fragments from the seabed. The area is of national significance due to the variety of features, which include erosion cliffs, creeks and saltpans. The current marsh has grown from east to west along the southern shore and this sequence has provided important insights into saltmarsh dynamics, sediment transport and sea-level changes around the British coast. At the eastern end the mature marshes at Berthlwyd have well-developed terraces and there is an eroding marsh cliff, while to the west at Landimore the marsh is cut by numerous creeks and pans (Fig. 102). Research has shown that the upper parts of the marsh are very stable, with the creek patterns changing very little over hundreds of years, while the lower reaches vary considerably due to the channels being blocked by fresh sediment and new courses developing.

The sediments of the marsh are unconsolidated and easily eroded, so at any point in time the marsh represents a delicate balance between sedimentation and erosion. Although apparently level it has a gradient of 1:240 towards the sea, interrupted by the presence of small breaks of slope, which indicate that it has built up and subsequently eroded, the secondary marsh developing at a lower level. The development of these terraces or ‘micro-cliffs’ is caused by scour associated with the main estuary channel.

On the Gower shore there has been very little land claim in comparison to sites elsewhere in Britain, where saltmarsh succession is often truncated by embankments and other coastal defences. On the north shore, in contrast, the urban development of Llanelli has led to a significant loss of habitat except near Penclacwydd where the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust have their only Welsh centre. As early as 1850 over 730 hectares had been destroyed (‘reclaimed’) by industrial development. The only substantial area to be enclosed on the south side is Cwm Ivy Marsh, an area adjacent to Whiteford Burrows, which was separated from the tidal marshes in 1638 by the building of an earthen sea wall, subsequently given additional protection by a drystone facing. The salt gradually leached away and the resulting freshwater marsh was divided up and fenced. Cwm Ivy is now considerably lower than the salt marsh outside the enclosing sea wall. In 1974 the sea overtopped the wall and to prevent a repeat the boundaries were subsequently increased in height.

FIG 101. The marsh at Llanrhidian, looking west towards Landimore along the ditch at the edge of the field system. (Harold Grenfell)

FIG 102. Creek patterns on Landimore Marsh. (Peter R. Douglas-Jones)

Development of the marshes took place naturally until the mid eighteenth century when a breakwater, or ‘training wall’ of slag blocks was built diagonally across the low-water channel of the river to aid navigation to the port of Llanelli. The aim of the training wall was to use the natural power of the tide to scour a channel to the port. The wall succeeded in its objective, but it also produced changes to the overall regime in the inlet and estuary and as a consequence areas of sediment deposition and erosion were drastically altered. Once there were many different channels in the estuary, today there is only one. In July 1764 John Wesley, travelling to Gower on one of his preaching tours, was able to ride across the estuary from Kidwelly with a local guide. Once the wall was completed this became impossible.

Marsh on the southern side of the estuary extended at the expense of the sand flats, and the moorings at Pen-clawdd, formerly served by a channel deep enough for seagoing vessels, rapidly became too shallow for use. Old maps and documents show that between 1790 and 1900 the marshes increased in area by 307 hectares and by 1960 had covered a further 252 hectares. The end of Llanelli as a port in the early part of the last century meant that the training wall fell into disrepair and it was finally breached in the 1950s. The estuary is still in the process of reverting to the natural pattern of water movement, with the main channel gradually moving south again. As the wall continues to collapse this process will continue until a situation close to the original sediment distribution is reached.

The vegetation of salt marshes is usually confined to the region between the mean high water of neap tides and extreme high water of spring tides, and like other intertidal communities it shows a marked zonation at different levels. One of the features of the area often remarked upon by visiting naturalists is the undisturbed and complete succession from open sand and mud flats through pioneer saltmarsh communities to upper salt marsh and dunes, marshy fields, or even woodland. The greatest diversity of plant species is found on these upper fringes of the marsh, especially in the transition zones where it merges with sand dunes, water meadows or freshwater marsh. Particularly interesting plant communities are found at Whiteford Point, Llanrhidian and near Loughor.

The major part of the saltmarsh vegetation consists of a relatively small number of salt-tolerant plants adapted to regular immersion by the tides, and there is a clear zonation according to the frequency of inundation. At the lowest level, where pioneer communities are dominated by glasswort Salicornia spp., annual sea-blite Suaeda maritima and common cord-grass Spartina anglica, the plants can stand regular immersion, while the species in the upper marsh can only withstand being occasionally covered by the tide. The muddy sediments in this area also support extensive beds of the nationally scarce dwarf eelgrass Zostera noltii.

Common cord-grass is a new species, which originated at the end of the nineteenth century as a result of hybridisation between the native small cord-grass Spartina maritima and the smooth cord-grass Spartina alterniflora, a naturalised alien introduced from America in the 1820s. Since its introduction on a small area of marsh west of the Burry Pill in 1935, to aid its ‘reclamation’ as grazing land, common cord-grass has colonised substantial areas of the estuary. It now dominates a broad belt of the lower salt marsh and has also invaded the creeks to the upper salt marsh. Eastwards it extends a considerable way up the estuary. The vast area of cord-grass below the sea wall at Pen-clawdd did not exist before 1955, but by 1975 it had spread over the whole area. These extensive swards are of little value to wildlife and are considered to be a threat to bird feeding areas. In Swansea Bay efforts were made to control its spread as it was thought to be a threat to the tourist industry, but on this side of Gower it was left unchecked. In the 1960s there were calls for the marsh to be sprayed from the air with herbicides, a potentially disastrous procedure for the other vegetation and intertidal life; thankfully this did not happen.

At the present time nearly 18 per cent of the saltmarsh area is covered by the cord-grass, although some long-standing areas are contracting for reasons not fully understood. There are similar reports from other parts of Britain. A number of causes for the decline have been suggested, including a lack of sediment accretion, water-logging, wave damage, oxygen deficiency, pathogenic fungi and a loss of vigour within the species due its lack of genetic variation. Whatever the future status of the plant in the estuary there is no doubt that the spread of common cord-grass has dramatically influenced the flora of the lower salt marsh. Unfortunately there are no published accounts of the vegetation of the inlet prior to its introduction, although there are several tantalisingly brief or introductory descriptions in the literature.

The low- or mid-marsh communities are, in contrast, dominated by a closely grazed sward of the common saltmarsh-grass with sea-purslane Atriplex portulacoides frequent along the creek sides and wherever there is reduced grazing pressure. Grazing has a noticeable effect on the structure and composition of saltmarsh vegetation, most obviously by reducing the height and diversity of plants. The common sea lavender Limonium vulgare, for instance, appears to be confined to relatively less-grazed sites such as south of Loughor and the western side of the Burry Pill. Several other species also occur, usually at low densities, notably greater sea-spurrey Spergularia media, sea aster Aster tripolium, sea arrowgrass Triglochin maritimum, English scurvygrass Cochlearia anglica and sea plantain.

In the mid to upper zones of the marsh there is an extensive sward of common saltmarsh-grass mixed with red fescue and other species such as thrift and sea milkwort Glaux maritima. The upper edge of the grazed salt marsh is marked by a belt of the tall unpalatable sea rush in which most of the species of the red fescue community occur, with the addition of parsley water-dropwort Oenanthe lachenalii, autumn hawkbit and sedge Carex spp. North of Llanrhidian the sea rush belt is several hundred metres wide and traditionally it was cut in late summer to provide rushes for bedding and to improve the grazing. This practice was revived briefly by local farmers during 1975 when bedding straw become prohibitively expensive. A few of the graziers still cut the rush for bedding, and for young store cattle there is nothing better, even though it breaks down more slowly than straw. Two striking and rather uncommon saltmarsh plants are locally abundant in the highest grazed marsh, marsh mallow Althaea officianalis, which has attractive pink flowers in July (Fig. 103), and sea wormwood Serphidium maritima with its aromatic pinnately divided leaves. This plant community, avoided by grazing animals, is a distinctive feature of the area. Much of this upper salt marsh is now managed as part of the Tir Cymen agri-environment scheme run by the Countryside Council for Wales, the local farmers having entered into 10-year agreements based on continuing current farming practices.

FIG 103. Marsh mallow, an uncommon saltmarsh plant, which is abundant on the marshes. (David Painter)

Further upstream the limit of salt water is characterised by extensive areas of brackish swamp dominated by common reed and sea club-rush Bolboschoenus maritimus, and at Llangennech this merges into reedmarsh and invading willow scrub, with abundant common club-rush Schoenoplectus lacustris. Diverse upper marsh swamps with tall stands of yellow iris Iris pseudacorus are present especially at the western end of the inlet in and around Cwm Ivy Marsh, which is of particular interest as a lowland fen meadow.

The marine invertebrate community appears to be typical of saline, muddy sand environments. In areas of fine sand cockles are abundant along with lugworm, amphipods and worms. In muddier sediments the sand-gaper Mya arenaria, peppery furrow-snail Scrobicularia plana and mud-snail Hydrobia ulvae are found in extremely large numbers alongside the polychaete worms Spio filicornis and Spiophanes bombyx and the common ragworm Nereis diversicolor. Predators in the community include the snail Retusa obtuse, which feeds on mud-snails, the polychaete Eteone longa, which eats other polychaete worms, and general crustacean scavengers such as the common shore crab and the brown shrimp Crangon crangon. The lower part of the estuary is one of the few places in Britain where the polychaete worm Ophelia bicornis is found. On the whole, however, there is a lack of knowledge about the marine invertebrate communities, which will have to be addressed if serious decisions about the conservation of the area need to be taken. We probably know, to the nearest 10 individuals, how many oystercatchers there are in and around the Burry at any one time, but almost nothing is known about the vast majority of the invertebrate species the birds depend on, or their abundance. Nearly all the research to date has been a by-product of studies concerned with cockles.

Lugworm are used by sea anglers as bait, and as angling has increased in popularity so has the demand for lugworm. In addition anglers are now much more prepared to purchase supplies of bait from tackle dealers where prices can be very high when demand outstrips supply, especially in the autumn and winter when cod and whiting are in season. This has led to large numbers of bait diggers visiting the inlet and estuary, some of whom are employed on a commercial basis. Commercial lug diggers and experienced anglers dig a large trench with a standard garden fork, turning the sediment over and returning the spoil to the trench, but some bait diggers dig a trench two or three forks wide and place the spoil in mounds either side of the trench. The latter approach obviously affects a wider area. Due to a concern about the effects on the cockle beds bye-laws were initially introduced by the Sea Fisheries Committee in 1987. Subsequently studies by Cardiff University showed that both methods killed substantial numbers of cockles, and additional bye-laws were introduced in 1992. These prohibited bait digging in the lower three-quarters of the inlet, to protect the cockles, and therefore indirectly created a conservation area for lugworm. There is no mechanism, however, for a Sea Fisheries Committee to directly restrict the harvesting of a marine organism unless it is classified as a ‘sea fish’.

Although no detailed account of the vegetation of the salt marshes in the inlet and estuary has ever been published, salt marshes in general have been classic areas for the study of plant ecology. Researchers have been attracted by the extreme nature of the habitat, the relatively small number of species involved, the clear zonation and the effects of easily measured environmental factors. In contrast to the great quantity of published work on saltmarsh vegetation, the ecology of the associated terrestrial invertebrates has been little studied, although excellent studies of particular groups have been made. Locally work was carried out in the 1960s and 1970s on the ecology of spiders and saltmarsh mites, and on the influence of ant colonies on saltmarsh vegetation, but more research is needed to properly understand the community as a whole.

An interest in the spider fauna of the Gower salt marshes began in July 1964 when, during the course of an ecological survey of the spiders and other arthropods of the sand dunes at Whiteford National Nature Reserve, a single female of an unknown but distinctive money spider was found by G. H. Locket. This was subsequently described as a species new to science under the name of Lasiargus gowerensis. At the time there was considerable discussion as to whether the new species should be included in the genus Lasiargus or that of Baryphyma, as it had characters similar to both. It was eventually concluded, however, that it was a member of the second genus and it is now known as Baryphyma gowerense, the only species to be named after the peninsula (Fig. 104). The original animal is now preserved in the Natural History Museum as the species holotype. A holotype is the particular specimen which is first described and which carries the name of the species. Holotypes are used because concepts of a species may change over time and biologists must have criteria for assigning the original name. Having the original specimen to go back to is essential.

The female animal varies in length from 2.7 to 3.3 millimetres, while the male is slightly smaller at 2.6 to 3.1 millimetres. The head is elevated into a distinctive lobe with long curved hairs at the front. The abdomen is black, rather elongate and tapering, covered with widely spaced hairs, and has four impressed dots. The legs are a uniform light yellow-brown and covered in long hairs, with two rows of long conspicuous hairs on the underside. The double row of hairs is particularly conspicuous in the female.

The original specimen was found in a deep accumulation of drift material on the sandy foreshore of Berges Island, a small extension of sand dunes from Whiteford Burrows, but further searching failed to locate specimens in the drift material. Only in 1967 was it realised that the searching was being undertaken in the wrong area. Instead it was decided to look at some of the adjoining habitats, and large numbers of immature specimens were found in the vegetation on the higher parts of the salt marsh, occurring only in a narrow band dominated by sea rush and red fescue. Later the spider was also found in a small estuarine marsh on the north side of Oxwich National Nature Reserve. In the mid-1990s surveys revealed that the spider was actually quite widely distributed, although extremely local in its occurrence, on purple moor-grass dominated fens in lowland Wales and Norfolk. Its ecological requirements are not understood, however, and its full distribution in Britain is not yet clear.

FIG 104. The Gower money spider Baryphyma gowerense, the only species named after the peninsula. A close-up of the male, showing the characteristic head of this species. (Natural History Museum)

In general the spider fauna of salt marshes is not rich and most species are found elsewhere, particularly in freshwater marshes, but a few, like Baryphyma gowerense, are characteristic of salt marshes or even confined to this habitat. Another money spider, Erigone longipalpis, is also fairly common on the Gower salt marshes.

The Burry Inlet and Estuary is better known for its edible cockles than for any other fishery. There are significant mussel beds, particularly at Pen-clawdd and Whiteford Point, but it is the cockle fishery that dominates the area. Although it is a fishery steeped in history, there are no written records or photographs until the 1880s, when the cockle gathering came to be regarded as picturesque and worthy of recording. Iron Age middens (refuse heaps) found in the dunes at Whiteford show that the resource has been utilised for thousands of years, but gathering on a larger scale did not take place until the cockles began to be gathered as a supplement to income as well as diet.

In the early 1900s it was estimated that there were as many as 250 gatherers in the Burry, mainly women as the men were at work in local manufacturing industries. Some authors stated that as many as 500 families supplemented their income from the beds, but it seems that this figure is somewhat exaggerated. In contrast the modern fishery supports less than 100 people, gatherers and processors, and few women are involved. Each person collected about 130 kilograms per day, the cockles being simply raked out of the sand when the beds were exposed at low water. They were then washed and sieved to remove excess sand and to reject any undersized animals. It was, and is, backbreaking work and the tides can be dangerous. Despite the gatherers knowing the area intimately there have been many tragedies in the past, not only due to the speed at which the tide comes in, but also because of the patches of quicksand which at times are almost impossible to identify. But even with the danger of the tides and the hard work it can be very tranquil out on the sands. The cockle gatherers say that they can hear the cockles ‘singing’. ‘They come to the surface of the sand and all open their shells for water at the same time. It sounds like a melody. When we tread on them, the singing takes on different tones’ (Roberts, 2001).

The collected cockles were placed in panniers across the backs of donkeys and taken to the shore (Fig. 105). So many donkeys were involved that the hillsides around the villages were said to echo with their braying all night. Cockles were either sold ‘shell on’ or more usually as boiled meat, the cooking being carried out in small processing plants close to the gatherers’ houses. The cockles are now cooked in modern processing factories to meet current hygiene standards, but in the past they were simply boiled up on crude stoves, constructed from a few stones and metal bars. The meat was sold to nearby markets at Llanelli, Swansea and Neath. Until a few years ago the resulting empty cockleshells were regarded as a waste product and simply dumped in large spoil heaps. They were often used, in the same way that gravel might be, to make cockleshell paths for the cottages, and such paths used to be a characteristic feature of the area. They were previously free to anyone who wanted them, but increasing interest in garden design now means that the shells for the first time have a value.

FIG 105. Cockle gatherer at Pen-clawdd around 1948. (Estate of Evan Evans)

The cockle women were well-known figures and had almost a regulation dress for going to market, with red and black stripes, black and white aprons, grey plaid shawls and flat straw hats with raised brims on which they carried a wooden pail of cockles. At the same time they carried two large baskets on their arms. Before the train ran to Pen-clawdd the women used to walk the seven miles into Swansea, balancing the wooden pails on their heads. They walked barefoot to save their shoes and on the outskirts of town would wash their feet and put on their boots to go into town. To this day this area of Swansea is still called Olchfa, which means in Welsh ‘the washing place’. The arrival of the railway meant that fresh cockles could be sent greater distances, and women went to lodge in towns to the east of Swansea where they could receive deliveries by rail and then market them. At its height the cockle industry was both extensive and complex and contributed significantly to the local economy.

In the 1920s major developments took place in the fishery. Firstly the horse-drawn cart was introduced in place of the donkey and panniers. This enabled an individual to gather over 520 kilograms per day, four times as much as previously. Secondly as manufacturing declined in the area men were drawn into the gathering to collect these enhanced loads and the harvesting of stocks intensified. Together these changes had such an effect on the cockle beds that in 1921 a minimum landing size was introduced by the South Wales Sea Fisheries Committee to protect the breeding stock. The main commercial beds cover little more than 2.5 square kilometres, a small area compared with the other main cockle fisheries in Britain, so they cannot support intensive activity. By 1952 so many cockles were being taken that the Committee was forced to consider setting a limit to control the amount taken in any one day, but it took until 1965 before the fishery was licensed, to limit the quantity of cockles removed.

Despite the constraints on exploitation, attempts have been made to improve the efficiency of the hand gathering. At one stage a hand dredge was designed which consisted simply of a toothed blade fixed in front of a rectangular mesh box to hold the catch. The gatherer moved backwards, pulling the handle of the dredge towards him with sharp sideways movements. There were many complaints that the dredge damaged the young cockles and permission for its use was withdrawn in 1969.

The fishery may cover a comparatively small area, but its production is nationally important. In the mid-1960s catches almost equalled that from the rest of the UK, although due to natural variability in the amount of cockle ‘spat’, which settles each year from the plankton, the size of the stock and the catch vary as well. Moderately good settlements of spat in 1965 and 1967 ensured that catches remained high until the early 1970s when physical changes in the substrate caused by the southward movement of the main river channel, probably due to further collapse of the training wall, resulted in a rapid decline in the number of cockles in the traditional beds. There was some erosion of the beds, but the main problem was a substantial reduction in the amount of fine sediment and an increase in coarse sediment, which is less suited to cockle settlement and survival. This period of particularly poor catches coincided with an increase in the number of oystercatchers. Despite there being no evidence of a link between the two facts the wrong conclusions were drawn and there was a demand from the gatherers that the birds be culled to protect the cockle stocks. The oystercatchers were claimed to be eating up to 250 grams of cockles per day and to be taking up to ten times as many cockles on an annual basis as the gatherers. This figure was based on studies on the Conwy Estuary in North Wales and took no account of the fact that many of the birds fed well away from the commercial cockle beds.

After a preliminary research programme consisting of cannon-netting and colour-ringing, which produced few results, over 9,238 birds were shot during the winter of 1973/4. There was a bounty of 25 pence on each bird. Peak counts of birds at that time were 20,000 per year. An international outcry followed the culling, which was halted prematurely, and no further culls have ever taken place. By the winter of 1975 the species had recovered to pre-cull levels and in the winter of 1986 these levels were exceeded. Since then there has been a reduction in numbers, suggesting that changes are determined by breeding success elsewhere. An analysis of the issue in 1977 concluded that the oystercatcher’s impact on the cockle population was much exaggerated and that cockle stocks would recover naturally. This has proved to be the case.

The cockle industry today is precisely as it was in the 1700s except that the horses and carts, which replaced the donkey and panniers, have themselves been replaced by tractors and trailers. This last change only happened in 1987. Whereas in the other major cockle fisheries in the Dee Estuary and Morecambe Bay vessel suction-dredging and mechanical harvesting using tractors has been allowed, the rake and the sieve still prevail in the Burry. The Sea Fisheries Committee approach, through the licensing regime, of providing maximum stability for a locally based industry has led to arguably the most sustainable cockle fishery in Britain. A limited number of licences, about 55, are issued each year for the hand-raking of cockles only. Gathering takes place all week except on Sundays to a quota of 300–600 kilograms per person per day. No night collection is allowed. The minimum cockle sizes are set via riddle size (a handheld measurement device) to allow the survival of sufficient spawning stock.

An approach was made to the Committee in 1991 to license the use of harvesters adapted from agricultural machinery, but a decision was deferred until a scientific study had been carried out. Trials of a tractor-towed cockle harvester subsequently took place in the Burry Inlet on one day in October 1992 (Fig. 106) and the effects on cockle populations, other invertebrates and birds were intensively monitored by a range of organisations. The tractor dredger was very efficient at removing adult cockles from shallow depths and the cockle gatherers were surprised at the large number of cockles gathered from areas they considered uneconomic to harvest by hand. The conclusions were that tractor dredgers could work out adult cockle beds very quickly and that their numbers would need to be strictly controlled. In the end the proposal was not pursued, although markets for seafood are increasing and extra demand is fuelling higher prices. It is not inconceivable that one day tractor dredgers will be at work in the estuary, but it would be a mistake. The current hand-raking fishery, locally based and with an enforceable daily quota system, removes 20 to 30 per cent of the cockle biomass annually in a non-destructive way.

FIG 106. Trial of a mechanical cockle harvester in October 1992. (Jonathan Mullard)

This sustainable harvest was stopped abruptly in July 2001, however, when a sample of cockles indicated the possibility of diarrhetic shellfish poisoning, which could cause a serious health risk to anyone eating them. It is caused by the presence of marine dinoflagellates Dinophysis spp. These dinoflagellates are widely distributed and sometimes form ‘red tides’, but not all species produce toxins. The result from eating infected products is vomiting and diarrhoea. Although the effectiveness of the test was disputed by the gatherers a temporary prohibition order on collecting was immediately placed by the local authorities. This ban was on and off from July 2001 until August 2002 with the longest break in this period being for 10 months, the greatest gap in gathering ever recorded. Although there was a previous break in 1996, as a result of the oil spill from the Sea Empress disaster, the positive DSP tests created a very difficult time for the gatherers, their families and the processors who make a living from the estuary.

New European directives on pollution, quality control and health have led to requirements for inward investment and the ‘picturesque’ processing sheds previously used have been replaced by new facilities. In 1994 a group of cockle gatherers created a joint company to process the shellfish, investing in a state-of-the-art cooking facility capable of producing many tonnes daily; there are now three such plants in the area and they take most of the cockles gathered. The benefits, however, have been top prices for quality produce and increased markets. The industry is no longer purely local and most of the cockles collected in the estuary are sent abroad to countries such as France and Spain, which have overfished their own cockle beds. The high demand has considerably increased the price of cockles, which have risen from around £200 per tonne in the mid-1990s to around £600 per tonne in 2004. The trade in Britain is now worth over £20 million a year. Unlike elsewhere in Britain, where migrant workers have been used, with results such as the tragic drowning of 20 cockle gatherers in Morecambe Bay in February 2004, the licensing system has so far meant that the licence holders are still the same people and families that have worked in the fishery for decades.

Specimens of almost all British marine fish species have been recorded from the area, but sea bass, mullet Chelon labrosus and flounder Platichthys flesus are regarded as typical of the estuary and surrounding coastal waters. Other species such as plaice, sole, cod and whiting are regarded as regular visitors. In the past herring Clupea harengus was also plentiful. The principal methods of fishing for these species are by fixed net or rod and line (Fig. 107). Boat netting is not allowed and no regular trawling takes place. Fishing takes place on a seasonal basis according to the availability of species, with bass and mullet in summer and autumn, flounder in autumn and winter and cod in winter.

Total commercial landings of these species from within the estuary are minimal, with only a few people now setting nets on an irregular basis, often ‘for the pot’. At low tide lines of abandoned metal stakes, formerly used to support fixed nets, can be seen at the tip of Whiteford Point, clear evidence of the much greater fishing activity in the past. Many of the fishermen were miners seeking to supplement their income, fishing the inlet and estuary with ‘field nets’ in between working shifts at the colliery. Much of the work was done at night, alone or in small groups. It was dangerous work, but the men knew every part of the shore and could operate in almost complete darkness if necessary. Most of the nets were fixed to the base of the poles, although the herring fishermen strung their nets three-quarters of the way up the pole, as the herring came into the inlet much nearer the surface than other fish. The catch, often 18 to 20 kilograms of fish, would, as with the cockles, be transported back to the shore by donkey.

FIG 107. Father and son hold a locally caught sea bass, weighing around 1.5 pounds (0.7 kilograms), before returning it to the sea, as it is underweight. (Harold Grenfell)

Bass are exploited all around the coastal area, through the use of rod and line, net, and to a lesser extent trawl. Due to the pressure on the stocks the inlet has been designated as a bass nursery area. For this reason, boat fishing for bass is seasonally restricted. Catches of bass and other species dependent on the estuary from Carmarthen Bay are significant, however, with the Sea Fisheries Committee estimating that over 25 tonnes of bass are landed annually.

As the season progresses, the anglers tend to concentrate upon sea trout Salmo trutta and, to a lesser extent, Atlantic salmon S. salar. The sea trout run starts in April and usually reaches a peak in late May and early June. The first fish to enter tend to be the larger, multiple-spawning ones, with the main run of maiden fish in late May and June. During July and August the smaller shoal sea trout, known as whitling, enter the rivers. The salmon that do enter the rivers tend to do so during the summer and autumn. The best months for sea trout fishing are therefore usually June, July and August, while salmon fishing tends to be restricted to September and October. Although these are the principal months, sea trout and salmon can be caught throughout the season from March to October. The Loughor has an average recorded annual catch of only 9 salmon and 195 sea trout.

Non-commercial species include both the sea lamprey Petromyzon marinus and the river lamprey Lampetra fluviatillis, primitive jawless fishes resembling an eel. Both fish need clean gravel for spawning and marginal silt or sand for the burrowing juveniles. The larva feeds by filtering fine particles during the five years of its freshwater life, while the marine stage develops a sucker-like mouth to feed on marine fish such as the shad Clupea alosa and salmon before eventually returning to fresh water to spawn and die.

Other species which occur in the area include two members of the herring family, twaite shad Alosa fallax and allis shad A. alosa. The estuaries feeding into Carmarthen Bay contain the only viable populations of shad in the UK and for this reason the area is of national importance. While twaite shad is found along most of the western coastline of Europe allis shad is rare and declining. Like the herring, shad feed on zooplankton, filtering it from the water through comb-like gill rakers. Both fish have streamlined bodies, distinct circular scales with a toothed edge on the lower margin, and a membrane partially covering each eye. The only reliable way of separating the two species is by counting the gill rakers; twaite shad have only 40 to 60 while allis shad have 90 to 130.

Sand eels, particularly the lesser sand eel Ammodytes tobicnus, are common in the estuary and provide an important food resource for many other fish and for seabirds. They are also the basis of a small bait industry.

If there is one feature of the inlet and estuary that attracts the interest of naturalists it is the importance of the area for birds. The sand, the alluvial mud with its wealth of invertebrate fauna, the salt marshes and sea-washed turf offer a wide range of habitats. The estuary is the most important wholly Welsh estuary for waterfowl, being valuable both as a wintering area and as a resting area during the spring and autumn passage for many artic-breeding species. The area lies on a major migratory flyway and many birds moving to and from other wintering areas on the Mediterranean and European coasts stop for a while on their journey. The area increases in importance when there are periods of severe cold weather in eastern England and birds move to the comparative warmth of the west.

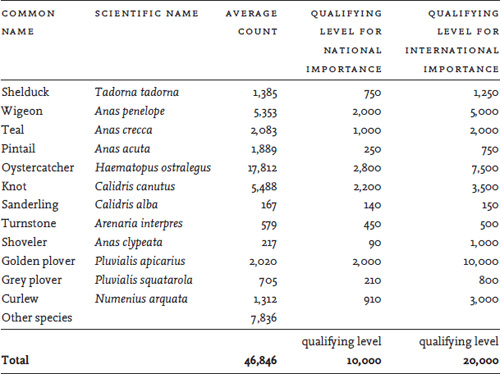

The Burry Inlet qualifies as a wetland of international importance due to the sheer number of birds present during the winter. It regularly holds more than 20,000 birds, with a total average count in the late 1980s of nearly 47,000 (Table 9). The inlet is also of international importance for the wintering populations of pintail Anas acuta and oystercatcher, with 1.7 per cent and 3 per cent respectively of the European population (Fig. 108). Oystercatchers wintering on the inlet originate mainly from mainland Scotland, the Faeroes and Iceland, as well as more local birds from the Pembrokeshire islands, and these patterns have remained unchanged since monitoring started in the 1960s. Once settled in the estuary birds probably winter there for life, and some initially ringed during the 1960s were still present in the 1990s.

TABLE 9. Waders and wildfowl on the Burry Inlet. Average peak winter counts 1983/4–1987/8. (Data abstracted from Prys-Jones, 1989)

The area is also of national importance for three species of wildfowl, brent goose Branta bernicla, shelduck Tadorna tadorna (Fig. 109) and shoveler Anas clypeata. Five species of waders also meet the same criteria: curlew, bar-tailed godwit, grey plover, dunlin and knot Calidris canutus. Vast densely packed flocks of thousands of knot are often a distinctive feature of the south shore. There are a small number of resident eider duck Somateria mollissima, which was adopted as the symbol of the Glamorgan Wildlife Trust. The eider duck is one of the enigmas of Gower ornithology. Although both males and females are present all year round and some prebreeding behaviour has been observed there is no evidence that successful breeding has occurred in the whole period from about 1900, when they were first recorded, until today. The population has fluctuated in number, rising from 30 birds in the 1950s to over 200 in December 1988, followed by a rapid decline to the 15 to 25 individuals present during the early 1990s. Numbers have now risen again to over 115 birds in 2001.

FIG 108. Around 3 per cent of the European population of oystercatchers overwinter in the inlet and estuary. (Harold Grenfell)

.jpg)

FIG 109. Male shelduck in the estuary. The area is nationally important because of the numbers of wildfowl using the area in winter. (Harold Grenfell)

Dylan Thomas’s ‘fishwife cross gulls’ are present throughout the year in varying numbers. The highest numbers occur in August and September, when regular flocking after the summer breeding season occurs. Of the five gull species recorded three species show a considerable increase: black-headed gull, lesser black-backed gull and great black-backed gull, while common gull numbers have remained static and herring gull has significantly decreased in numbers. This decline is almost certainly linked to the closure of nearby refuse tips.

The extensive reedbeds at Llangennech support breeding reed warblers Acrocephalus scirpaceus and sedge warblers A. schoenobaenus as well as reed buntings Emberiza schoeniclus.

A significant addition to the bird list is the little egret Egretta garzetta, first recorded in 1984 (Fig. 110). Until comparatively recently the little egret had been a rare visitor, with only single birds seen, but now counts of 130 birds or more are common during the winter. Severe cold weather can prove difficult for the egrets, but the relatively mild winters on the estuary mean that it can overwinter here. It bred for the first time in Britain in 1996 and there were more than 30 pairs nesting at nine sites in 1999. It is probably only a matter of time before it breeds in the inlet and estuary. The little egret has been joined recently by another ‘exotic’ bird, the Eurasian spoonbill Platalea leucorodia. Between 50 and 100 individuals are recorded in Britain each year, mostly on passage or as wandering juveniles. To date only single birds have been seen here, but it did breed in Britain in 1998, for the first time in many centuries.

FIG 110. Little egret, first recorded in the area in 1984. Over 130 are now present during the winter months. (Harold Grenfell)

Systematic work on the wildfowl, wader and gull populations by dedicated local researchers, especially Robert Howells, started in 1949, and over more than half a century of continuous recording an incredibly detailed knowledge of the area and its value for birds has been built up. In 1969 the British Trust for Ornithology and the RSPB started the Birds of Estuaries Enquiry. From this date until 1984 weekly counts were made of the whole inlet, and after 1984 the weekly counts were replaced by counts on at least eight days per month. In total 56 species of birds have been recorded in this way. Such an intensity of observation is probably unequalled anywhere else in Britain and certainly was a major factor contributing to the recognition of the area’s national and international importance.

The distribution of birds in the inlet and estuary varies according to the season and the state of the tide, but there are some constants that make it easier for the bird-watcher to locate various species. Ducks and waders in particular have different requirements for their roosts. Waders need exposed ground, the smaller species preferring short grass, sand or shingle while the larger species, especially curlew and redshank Tringa totanus (Fig. 111), are able to roost in fairly long vegetation. Ducks usually roost on the water in a belt near the edge of the marsh. On high spring tides, however, virtually all birds move to Whiteford. The majority of birds feed on the marsh from Whiteford to Salthouse Point, although oystercatchers, knot and pintail feed on the sandbanks in the centre of the estuary. A separate group of oystercatchers and turnstones Arenaria interpres feed on the mussel scars to the north of Whiteford Point.

Despite the wealth of bird life the south side of the inlet is not a popular place for bird-watching. Whiteford Point is the area most visited by bird-watchers, although it is a long walk out to the hide at the end of the spit and good views of the birds are only possible at certain states of the tide. There are few large concentrations of birds conveniently near roads north or south of the inlet where they can easily be seen. In this respect the National Wetlands Centre at Penclacwydd on the north side, run by the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust, is fulfilling a demand and is very popular, especially with family groups.

Wildfowling, a traditional coastal activity formerly pursued for food, is now continued as a sport. Until the early 1950s foreshore and marsh shooting was more or less unregulated, but with the passing of the Protection of Birds Act in 1954 some of the wildfowlers shooting in the inlet worked to create organised clubs to obtain definite legal rights to shoot in certain areas and to exercise some control over the activities of their members. Two Wildfowlers’ Associations were eventually established, covering the north side and the south side respectively. Both administer their shooting responsibly and have a good conservation record. Today the activity is governed by the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, which allows the shooting of ducks and geese on the foreshore between 1 September and 20 February inclusive. In the inlet and estuary it is mainly wigeon Anas penelope that are targeted, together with some teal A. crecca and mallard A. platyrhynchos. The total estimated annual ‘bag’ is around 200 birds, an insignificant figure in conservation terms considering the number of birds that overwinter in the area. The West Glamorgan Wildfowlers’ Association leases shooting on some 2,000 hectares of Llanrhidian Marsh from the National Trust and the area is wardened by members of the clubs in conjunction with the National Trust and the Countryside Council for Wales. In 1964 the Association voluntarily gave up shooting rights over parts of the marsh adjacent to Whiteford National Nature Reserve. This gesture by the wildfowlers meant sacrificing the most important ‘flight line’ used by wigeon, and as a result numbers have increased.

FIG 111. Redshank at Pen-clawdd. (Harold Grenfell)

The short-eared owl Asio flammeus, a scarce winter visitor, can often be seen in the late afternoon, in autumn and winter, hunting over Llanrhidian Marsh. It bred near Pen-clawdd during the nineteenth century and there is evidence to suggest that breeding occurred in some of the dunes during the early 1920s, but there have been no recent records. There have, however, been a few sightings of birds during the summer, such as the two individuals seen on Fairwood Common in June 1986, which suggest that it has bred in the area comparatively recently.

The salt marshes have been used as common-land grazing for hundreds of years. A survey of Gower Anglicana in 1583 stated ‘The lord and tenants of this Lordship may enter all commons as Llanrhidian Marsh and any other and have done tyme out of minde, without contradiction as farre as we know without lett or interruption.’ All the grazing marshes are now registered common land and the sea-washed turf sustains large numbers of sheep as well as ponies and cattle. Currently about 300 Welsh mountain ponies, 6,000 ewes and their lambs and 30 cattle graze the area (Fig. 112). This intensive grazing creates a sward that is attractive to overwintering wildfowl and waders, while less intensive grazing produces a tussock structure that is used by breeding waders.

FIG 112. Ponies and sheep grazing on the marsh at Wernffrwd. (Harold Grenfell)

In total the marshes on the southern side of the estuary cover an area of 1,098 hectares, approximately half of the salt marsh in the estuary. All this salt marsh is grazed, in contrast to the salt marsh on the north side, which is one of the best national examples of ungrazed salt marsh. The ownership of the area is divided between the Crown Estate, the Duke of Beaufort’s Somerset Trust, the National Trust and a private landowner. Many of the commoners are farmers who have lands within the Manors of Landimore, Weobley or Llanrhidian with rights over the manorial wastes including the marshes.

From time immemorial the commoners have moved their sheep according to tide and season, and as there is a substantial tidal range in the Burry the farmers need to consult their tide tables when managing their stock. A 7.0 metre tide causes no problems and will not cover any of the grass, while a 7.5 metre tide covers about half the marsh and an 8.0 metre tide covers the whole marsh. Wind speed also has an effect on the height and speed of the tide, while the tide tends to fill the many pills and reans first, cutting off the exit from the marshes. As a result some sheep have to be moved on a 7.5 metre tide and all sheep on an 8.0 metre tide. Each farmer knows the area where his sheep may be grazing and therefore the time available before high tide to move animals.

In contrast to the sheep, which will drown if left out unattended, the ponies know the marsh well and will walk in with the tide. Sometimes they will remain standing on the higher ground, even up to their stomachs in the water, knowing that the tide will eventually go out. Occasionally ponies standing in this way are forced off by the depth of water and then swim in single file to the shore led by the dominant mare. Unfortunately well-meaning but uninformed members of the public who do not know the ways of the marsh see ponies standing deep in the water, assume that they are going to drown and ring the police, the RSPCA and other organisations. Despite regular publicity about the issue the perception continues.

The grazing is good and the animals thrive on it. Being covered by the tide twice a day in the course of the tidal cycle brings nutrients and silts which feed the sward throughout the seasons. There is a problem for the sheep, however, in constantly eating salt-washed, silt-laden turf in that they lose their teeth early. The lambing cycle of a ewe on the marsh is only about three crops whereas a hill farmer would expect five or six crops. False teeth were tried and fitted to the sheep some years ago, but they did not appear to be successful. But salt-washed mutton is a local delicacy and some butchers place special orders for marsh sheep and lambs. Until about 1904 the fleeces from the sheep were spun into yarn and woven into quilts and blankets in the mills at Llanrhidian; today they are virtually worthless.

Nearer the enclosed fields bounding the upper shore, the ‘inbye’ land, there are large areas of sea rush where there is always some well-sheltered grass for the harder winter weather. Little is known, however, about the grazing behaviour of animals in salt marshes. Selective grazing, trampling, dunging, nutrient redistribution and the interactions of different grazing species are all likely to be important factors in determining the nature of the saltmarsh vegetation. Some initial studies of pony grazing on the salt marsh were undertaken by the University of Swansea in 1975 and 1976, but these have never been followed up. These preliminary studies showed that a wide range of saltmarsh plants was grazed and that the preferred plants varied widely between different individuals and at different times of year. Analysis of dung showed that in general saltmarsh-grass and red fescue form the major part of the diet. Some groups of ponies do graze and trample common cord-grass, maintaining short, open swards in places, while other areas remain ungrazed. Similar work undertaken in the early 1970s in Bridgwater Bay, Somerset, found that areas of cord-grass could be converted into saltmarsh-grass pasture in five to ten years by sheep grazing, but there does not seem to be enough grazing pressure on the Gower marshes for this approach to be effective.

At the height of concern about the invasion of common cord-grass and shortly after the oystercatcher cull, it was noted that the inlet and estuary had ‘a history of thoughtless interference’ (Nelson-Smith & Bridges, 1977), with proposals intended to favour only one interest conflicting with the needs of others. Also in the writer’s mind at the time was the proposal by the Loughor Boating Club for a tidal barrage across the Loughor. The Club had contracted Swansea University’s Engineering Department in 1969 to carry out a feasibility study for a barrage ‘to contain a freshwater lake of 400–600 acres [162–243 hectares] with a new Swansea to Llanelli link road across the top’. The intention was to use the area for water sports. Although no further progress was made the issue is still raised in the local newspapers every few years. Today, with the international importance of the estuary well understood and better liaison and consultation between the various local and regional interests, the barrage is unlikely to be built. There is, however, growing concern about an issue that was scarcely recognised in the 1970s, and that is a rise in sea level. Changes in sea level due to global warming are likely to cause great changes to the inlet and estuary over the next hundred years.

Sea level is currently rising at a rate of about 2 millimetres per year and the forecast is that the level will rise approximately 40 centimetres by 2100. The rate of the rise depends on three different factors, some of which researchers are more confident in than others. The first definite factor is that increasing global temperatures are causing sea water to expand as it warms. Secondly there is a moderate certainty that melting glaciers will add to the volume of the sea, and finally there is a concern that the instability of ice sheets could contribute to large-scale and sudden sea-level rise.

Salt marshes and intertidal areas are obviously sensitive to a rise in sea levels, but they are not passive elements of the landscape and as the sea level rises the surface of the marsh and sands will also rise due to inputs of sediment and organic material. If this input keeps pace with sea level then the marsh and sands will grow upwards. If it does not, then they will be steadily submerged. In this situation vegetation will be covered by the tide for progressively longer periods and it may die, giving way to bare intertidal areas or even open water. Direct losses of habitat due to sea-level rise can be offset by higher areas converting to marsh, but there is comparatively little room for this on the south side of the estuary. If current predictions are correct, in a hundred years or so the sea will once more wash against the limestone cliffs of north Gower and the inlet and estuary, as we know it today, will have disappeared.