The road to Pozières

Captain Ivor Margetts, a Tasmanian schoolteacher with kind eyes and the long frame of a ruckman, headed off with the 1st Australian Division for the fighting at Pozières. He passed through Albert and doubtless looked up – everyone did – at the gilded Virgin, dangling above the square. Lieutenant Charles Carrington of the British 48th Division, also on his way to Pozières, passed underneath by moonlight. The men, he wrote, were awed. ‘The melodrama of it rose strongly in our hearts.’ The Australians had decided the Virgin was about to dive and christened her ‘Fanny’, after Fanny Durack, who won a gold medal as a swimmer at the Stockholm Olympics of 1912. Margetts by now would have swapped his felt hat for a steel helmet and removed his Sam Browne belt and leggings. Only the three pips on his shoulder straps would now mark him as an officer.

Margetts had been in the big battles of Gallipoli; most of his comrades in the reconstituted 1st Division had not. They had been in the frontline at Armentières, near Fromelles, but never in a big attack. None of the Australians, neither Gallipoli veterans nor fresh recruits, was aware of what they were now marching into. Gallipoli had never been an artillery battle in the style of the western front. The Turks only brought up heavy howitzers, and then just four of them, a month before the allies left. And, curious as it seems, these men didn’t know how cruel the twenty-day-old Somme battle had been. They, like the newspaper readers of Manchester and Sydney, thought the offensive was going well. The censors had been busy. The wider world was unaware of what Haig had been trying to achieve on that first day and that his losses had been the worst in British history. An Australian sergeant wrote home that ‘a big push has been going on successfully since the 1st of July … Many English regiments pass us who have been relieved from the front area … They have been very successful and are all singing as they march along, every man wearing a German helmet.’

THE ELFIN-LIKE BILLY Hughes, all ears and crinkles and rasping adjectives, had climbed on to a wagon in an orchard near Armentières to address men from the 1st Division the previous month. Wagging a bony finger that might have been borrowed from the Grim Reaper, he told them that the thoughts of all Australians were with them. Whatever happened, Australia would not forget them or their dependents.

The Australian Prime Minister had been stumping up and down the British Isles delivering patriotic speeches. He was much feted: he understood the rough demagoguery of war in a way Herbert Asquith did not. Hughes had been given the freedom of the cities of London and Manchester, handed honorary doctorates from universities and appointed to the Privy Council. Once he had humped a swag around Queensland and the world had trampled all over him. Now the assisted migrant, born of Welsh parents in London, was a man to know. He was a trade unionist and defender of battlers, yet the war had somehow transformed him into a man who was saying the things that those in power wanted to hear.

If this was confusing to others, it wasn’t to William Morris Hughes. He was now welcome at places he once would have been thrown out of as a Welsh upstart. He stayed at Windsor Castle with the King. Generals, archbishops and press barons took him seriously.

They were using him, he was using them, and Keith Murdoch, the Australian journalist now working in London, was using the entire cast to turn himself into a man of eminence. Murdoch waited on Hughes, ran his errands and literally became an arm of government, but forgot to tell his readers back in Australia that he was a player as well as an observer. Lloyd George seemed to see Hughes as a rougher version of himself, without the music or the power to make audiences nod along with his rhythms, but charged with the same energy, no gentleman, no respecter of conventions, but a man determined to have his way. As John Grigg, Lloyd George’s biographer, wrote: ‘Both were men of the left whose distaste for ideology and, above all, concern for national defence forced them into an alliance with the right.’

And now, on this day in France, Hughes spied from his perch on the wagon an elderly infantry private, William James Johnson, who had been a Labor member of Federal Parliament for three years until 1913. Hughes shook hands with Johnson, who quipped: ‘Well, Billy, have they made you a doctor of divinity yet?’

A few months earlier, on the first anniversary of the Anzac landing, Hughes had said in London that the Gallipoli campaign ‘had shown that through self-sacrifice alone could men or a nation be saved’. Then he said something that was very strange: ‘And since it has evoked this pure and noble spirit, who should say that this dreadful war was wholly evil now that in a world saturated with the lust of material things came the sweet purifying breath of self-sacrifice?’

Hughes was high on the careless rhetoric of war. He was going back to the political salons of London; Private Johnson, the former parliamentarian, now aged forty-five, was going to fight Germans at Pozières, where he would die after being hit in the head by a shell fragment.

MARGETTS HAD WRITTEN home a few months before he set off for Pozières:

I have been rather busy writing to broken hearted mothers, giving them details regards killed & missing men. It’s not a nice job but I am getting a dab at it ‘every one different and quite original’. One has frequently to cut out some of the details. People ask if you can tell them the last words & who was holding their hands when they snuffed out. I could not very well say that the poor chap was cursing fairly well & was being held down on the stretcher by three or four dirty stretcher bearers who also put in an occasional curse at the Turks for doing the damage or describe some of the actual scenes which one sees.

Letters of condolence were a burden for all frontline officers: how to tell relatives enough of what had happened – but not all? As Margetts covered the last mile or so towards the Pozières front, past shell holes with muddy bottoms, past British and German corpses and with the sweet smell of German tear gas in his nostrils, it may have occurred to him that he would shortly be writing such letters again.

SERGEANT BEN CHAMPION, another 1st Division man, had given up his dental apprenticeship to enlist as an eighteen-year-old. At his first billet in France, near Hazebrouck, the farmer’s wife upbraided him and other Australians for washing with soap in a pond the cows drank from. The guests pacified her by paying for coffee and cognac, and she allowed them to sit in her spotless kitchen, where the fire glowed, as did the brass work.

Now Champion was on the long march towards Pozières. Packs were discarded, except for a waterproof sheet that was rolled up and worn as a bandolier. The men received a strip of pink cotton to sew on the back of their tunics so that British pilots could identify them. Champion collected an extra 250 rounds for his .303 Lee Enfield rifle, two sandbags and two bombs before passing under the Hanging Virgin. The march through Albert was eerie, he wrote. English guides took them into Sausage Valley, which led to Pozières and was packed with artillery pieces seemingly locked wheel to wheel. The guns roared and the Australians reeled at the sound.

… we realised that at last that we were in a war. The Northern sector to us was just a nursery to prepare the way for this. Heaps of used ammunition, shells and war litter of all kinds, broken rifles, equipment, guns, boxes of biscuits, and ammunition were strewn everywhere. Soon we came to an area with the sickly smell of dead bodies, and half-buried men, mules and horses came into view. Here was war wastage properly. Germans and British mixed together, lying in all positions, and there wasn’t a man but thought more seriously of what was ahead.

The Australians walked into gas and pulled on their masks. Some thought the smell reminded them of hyacinths. Now they could see Pozières ahead, low heaps of red-brick rubble and splintered orchards. Tired by the long march and frightened by the nearness of death, they began to dig new trenches and crack jokes.

Next day the Germans began hitting them with 5.9-inch howitzer shells, known as ‘Jack Johnsons’. They exploded in black smoke, which is why they were named for the first black man to hold the world heavyweight boxing title. Australians trying to dig out comrades who had been buried by shell-bursts were hit in the arms and shoulders by machine-gun fire. Champion said the men were told that once the attack began no-one was to help a wounded man. His battalion was to go forward in waves, every fourth man in the first two companies carrying a pick or a shovel. As soon as the German trench was taken the Australians were to change its parados, or rear wall, into a parapet. The men of the first wave had their sleeves rolled up to the elbows to distinguish them from the following waves. Officers, now dressed like rankers, mingled with the men and encouraged them not to drink too much from their water bottles.

And so, on July 23, Champion hopped the bags at Pozières. ‘The tension affected the men in different ways,’ he wrote. ‘I couldn’t stop urinating …’

LIEUTENANT CHARLES CARRINGTON of the British 48th Division had moved up to the front earlier. His division was to attack Pozières on the left of the Australians but first it had to fight on the eastern outskirts of Ovillers. On the way, near La Boisselle, Carrington tried to sleep in a German dugout. ‘This was the first German dugout we had seen, and I felt the romance of our position too strongly to sleep just then.’ Carrington was nineteen, a boy from a country vicarage who had enlisted as a private in Kitchener’s New Army. ‘There was a strong, stale, fetid smell of sweat and decaying paper and old clothes, permeated by the solid flavour of the earth that lay fifteen-feet thick above our heads.’

Next day, after six months in France, he saw his first corpse, a German. A sergeant, pleasant-mannered and with a silky civilised voice, told Carrington that he had once pulled the teeth out of a German corpse in Belgium and made a necklace. Carrington came upon more German dead in a shell hole. ‘They lay, not in picturesque attitudes, but in the stiff unreal pose of fallen tailor’s dummies; they looked less human than waxworks; all the personality had faded from their faces with the life. Big men they had been: they had now a horrid plumpness. In awful fact they were bursting out of their clothes.’

On his way to the Ovillers front Carrington heard a whistling sound. The shell fell behind him. Phut. A dud. Then came another similar sound. The shell hit the ground like a rotten egg. Then more. Carrington smelled something. ‘It was sweet, pungent, sickly, heavy. Almonds were something like it.’ The smell thickened and caught at his throat. His eyes and nose began to run. The Germans were firing tear gas.

Soon Carrington was shooting at grey-clothed shadows during a bomb fight outside Ovillers. A German bullet hit one of his men in the brain. He lost consciousness at once but refused to die. His body writhed for two hours. An old corporal held his body and arms as a dozen others sat around in a ditch reeking of blood. Water came up in tins. The men swallowed it in huge draughts, even though it tasted of petrol.

Carrington looked up towards the next ridge and Pozières village, which other battalions of his division were to assault from the west while the Australian 1st Division attacked from the south.

The Australians were going in the line there to attack it, and as we stood and talked, the skyline heaved and smoked, throwing up fountains and jets of soil and grey smoke as if it were a dark grey sea breaking heavily on a reef. The bombardment grew thicker and thicker: clouds of smoke sprang up and drifted across its torn group of trees; the spurts of high explosive rose close together, till it seemed that the very contour of the hill must be changed.

GENERAL HUBERT GOUGH, the commander of the Reserve Army, had been told by Haig on July 18 to ‘carry out methodical operations against Pozières with a view to capturing that important position with as little delay as possible’. Several days later Haig visited Gough ‘to make sure the Australians had only been given a simple task’. He wrote in his diary that this was the first time the Australians would be ‘part of a serious offensive on a big scale’. One can sense what he was trying to say, but it did rather play down what had happened at Fromelles three days earlier.

Haig wasn’t sure what to think about the Australians. He liked the appearance of them. ‘The men were looking splendid, fine physique, very hard and determined-looking … The Australians are mad keen to kill Germans and to start doing it at once! I told the Brigadier to start quietly, because so many unfortunate occurrences had happened through being in too great a hurry to win this campaign!’ But Haig also worried about the Australians’ reputation for rowdiness away from the front. The Australians were free spirits and Haig liked conformity. He did not equate fighting Turks with fighting Germans, which showed some failure of the imagination, since the Turks had beaten the British, French and Anzacs on Gallipoli. Haig worried about the quality of the senior Australian officers and didn’t think much of his countryman Birdwood. Too indulgent of Australian ways.

Haig perhaps should have worried more about putting the Australians under Gough. The Reserve Army commander had no sooner received his order to attack Pozières – methodically, the order said – than he summoned Major-General Harold Walker, commander of the 1st Australian Division.

Gough had decided to forego the military courtesies. He would not wait for Birdwood and White and the staff of I Anzac Corps to come up. Gough and the staff of the Reserve Army would tell Walker what to do. His first words to Walker were: ‘I want you to go into the line and attack Pozières tomorrow night.’ Gough hadn’t looked at the ground; the story goes that he had spent much time boar-hunting with his staff. He wasn’t going to let ‘Hooky’ Walker look at the ground either.

One hesitates to say the episode is typical of Gough, but it certainly demonstrated three of his failings. He was arrogant; he was an optimist; and he was careless when it came to preparations and staff work. The cavalry charge was forever playing in his head. He wanted to gallop, to crash through; he didn’t want to be held up by detail or hear the voices of doubters. He had a hot temper. Edmonds, in a letter to Bean in 1930, said Gough was a good soldier ‘but too rash and headstrong’. In another letter he told Bean that he thought Gough ‘first class as [a] divisional and corps commander, but his gifts of energy and dash were out of place in command of an Army …’

It is questionable whether Gough much understood modern war or indeed anything other than cavalry. In those days officers with his mindset were called ‘thrusters’. That’s why Haig seems to have favoured him, even though Haig, also a cavalryman, was by nature more prudent. Gough’s rise had been fast and bore little relationship to achievements. Edmonds said Haig was ‘perfectly infatuated’ with Gough.

Educated at Eton, Gough had been prominent in the Curragh ‘mutiny’ of 1914, when British officers in Ireland refused to impose the Home Rule Bill on the Protestants of Ulster. He came to the war commanding a cavalry brigade. Soon he was running a division, then a corps and now an army. He was only forty-five and in most of his photographs a dyspeptic air seems to hover about him. His face often wears a choleric look and his eyes are without a hint of charity, but his friends insisted he was witty and charming. As the war went on his friends became fewer and his enemies, many of them dominion troops, became an army of their own.

It was lucky for Australia that Gough had tried his bluster on Walker. Hooky was not only a man who thought things out carefully: he was never going to be awed by someone like Gough. Walker was unusual among the Great War generals: he seemed to be without the conventional ambitions. Bean described him as having the style and appearance of an ‘English country gentleman’ but this masked a hard will. Walker didn’t see the conflict as a way to promotion and honours; he was a soldier’s soldier and wasn’t going to defer to a superior if he thought the orders he was being handed were unsound. Australia owes this Englishman much more than it has ever acknowledged.

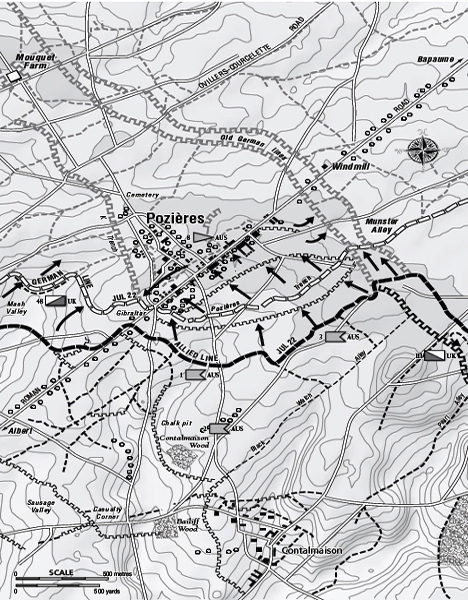

Walker politely told Gough he wanted a postponement. Walker had been given the choice of attacking Pozières from the south-west (along the Bapaume road, the scheme preferred by Gough) or by a flanking assault from the south-east. Walker wanted to see the ground. He also knew that no jumping-off trenches had been dug; nor was there a proper artillery plan. Gough agreed to the delay. That night Walker scribbled in his diary: ‘Scrappy & unsatisfactory orders from Reserve Army – Hope I shall not be rushed into an ill prepared for operation, but fear I shall!’

Walker was arguably the best allied general on Gallipoli. He was the first officer on Birdwood’s staff to land, splashing ashore around 8 am on the day before his fifty-third birthday. Three hours later he was in charge of the New Zealand Infantry Brigade after its commander had fallen ill. After dark Walker was on the beach at a panicky meeting of Birdwood’s commanders. They wanted to evacuate, although they didn’t quite say so. The note sent to General Sir Ian Hamilton, the allied commander-in-chief, suggested unanimity. Walker had argued against evacuation. We don’t know his exact words but he is supposed to have spoken to Major-General William Bridges, the commander of the 1st Australian Division, ‘in terms which could have jeopardised his career’.

Next month Walker took temporary command of the 1st Division after a sniper’s bullet killed Bridges. When the Turkish attack of May 19 left 3000 of their dead lying stinking in front of the Anzac trenches, it was Walker who sauntered into no-man’s land to speak to the Turks who had come out under a white flag. Walker handed out cigarettes and told the Turks they needed to arrange something formal. A few days later the famous truce of May 24 took place.

Walker became one of the ‘characters’ of Anzac, not tall but strongly built with a receding hairline and a neat moustache. He wore his cap at a jaunty angle and was likely to turn up anywhere. Sergeant Cyril Lawrence, the engineer who wrote perhaps the finest Australian diary of the Gallipoli campaign, said Walker would appear attended by an entourage of ‘flunkeys’. He was ‘a small man dressed in light khaki and shorts, and with not a sign of rank about him’. Walker, Lawrence said, seemed to enjoy the Australians uncouth replies to his questions. Walker helped shape the attack on Lone Pine and was later badly wounded by machine-gun fire. He would not allow his wound to be treated until another soldier, hit at the same time, had been taken to a dressing station.

Walker took over the 1st Division again in France in March, 1916, and about six weeks later General Haking, working on one of his schemes for an attack on Fromelles and Aubers Ridge, suggested that the 1st Australian Division, which was nearby, might be loaned to him for the assault. One of Walker’s staff wrote in 1934 that Walker thought the scheme unsound and ‘refused to have anything to do with it. But for his firm stand, the 1st Division might have been slaughtered on the altar of Haking’s ambition, instead of the 5th Division.’

And now, two months later, Walker was standing up to Gough and his artless plan to rush at Pozières from the front. Gough, it should now be said, later disputed that he wanted to go at Pozières from the west. He said he always wanted to attack it from the south-east. In 1927 he read the proofs of Bean’s account of Pozières in the Australian official history. ‘I can hardly believe a word of this story about my meeting with General Walker!!’ Gough harrumphed. ‘I wonder if any of my staff would confirm it. I was not “temperamentally” addicted to attacks without careful reconnaissances and preparation, as the conduct of all my military operations fully bear out, including this one!’ He said he always intended to attack Pozières from the flank ‘but it seems the Australians wish to claim all the credit for all things’. Gough said he didn’t think Walker had much to do with the choice of the direction of the attack. He also accused Bean of repeating ‘camp gossip’.

In his own book The Fifth Army (the Reserve Army became the 5th Army) Gough gives the battle only a few pages and somehow manages to make it sound like an abstraction. He does, however, praise the Australians and their leaders, Birdwood (‘always easy to work with’), White (‘one of the best Staff Officers we had’), Herbert Vaughan Cox, the commander of the 4th Division, and Talbot Hobbs, the artilleryman who later took over the 5th Division. He makes no mention of Walker.

There is no reason to believe Gough’s version and every reason to believe Walker’s, which is corroborated by others, notably White. In a letter to Bean in 1928 Walker said that on the 20th – two days after Gough had told him to attack on the 19th – there was a conference in Albert at which Birdwood and Gough were present. There was a further conference at Gough’s headquarters the next day.

It was at the Conference on the 20th that Gough definitely wanted me to attack from the Thiepval direction … He wanted me to attack over the same ground which the Division commanded by I think Ingouville-Williams [of the much-battered 34th] had heroically attacked & failed. I said no! that the left flank was exposed to the Thiepval Ridge – Matters went so far that I asked Gough to give me a Staff Officer to accompany me up to the line where I would point out the disadvantages of attacking from the SW & my plan to attack by or from the South East.

Walker said he took a Reserve Army staff officer called Beddington up to the line and explained his plan for attack to him. ‘The last words I said to Beddington were “What are you going to tell Gough” & he said – “I shall recommend your plan” – (I remember this incident absolutely).’ Gough, Walker wrote, adopted his [Walker’s] plan. Walker called Gough’s earlier orders ‘disgraceful’ and suggested he was a ‘cunning devil’ for trying to conceal his original scheme. ‘If I had not fought most strenuously for my plan & insisted on a staff officer accompanying me & being shown my plans, we should have been compelled to undertake an operation which we would have failed … I always look back on those days as the very worst exhibition of Army commandship that occurred in the whole campaign tho’ God knows the 5th Army was a tragedy throughout.’